aggression

Aggression ( Latin aggressiō from deponens aggredī to move towards [sth./jdn.]; To approach; to approach; to attack) is a hostile, aggressive behavior of an organism. It is a behavior pattern that is biologically anchored in animals and humans for the defense or extraction of resources and for coping with potentially dangerous situations. These ultimate causes are triggered , activated or inhibited in humans by proximate causes in the personality or the environment and are motivated by various emotions .

The American physiologist Walter Cannon coined the term fight-or-flight in 1915 ; In 1936, the physician Hans Selye created the “General Adaptation Syndrome” as a model of the human reaction to chronic stress (for details see stress reaction ).

Specific situations and stimuli are required to trigger aggression. In humans, emotional aggression is often caused by negative feelings, for example in response to frustration , heat, cold, pain, fear or hunger . Whether and how aggression is expressed in behavior is largely subject to the respective social norms .

The negative assessment of aggression, which emphasizes (only or predominantly) the destructive side, is not generally shared. In psychotherapy, for example, gestalt therapy regards aggression as a form of arousal that z. B. serves to remove obstacles or to make new things from the environment assimilable for the organism . Aggression only becomes destructive or violent under certain external or internal conditions.

Aggression in the animal kingdom

Aggressive behavior is widespread in the animal kingdom . It is interpreted by behavioral biologists to mean that it serves the direct competition for resources or for food ( interspecific competition and intraspecific competition ), the defense of territory , the establishment or change of a hierarchy and also the competition for a possible sexual partner . Grabbing prey for food is also associated with some form of aggression in animals, whereas techniques for killing prey were used early on in humans (see hunters and gatherers ). Aggressive behavior in the true sense of the word is often referred to as agonistic behavior or as attacking and threatening behavior and associated with specific triggers (“ key stimuli ”). To regulate aggressive impulses there is the instinctively disposed anti- aggression inhibition in animals and humans .

Aggression in humans

Human aggression is behavior that is either done with the intention of harming other people or to lower their hierarchical status. One can distinguish between emotional and instrumental aggression. In the first case, the aggressive behavior is a reaction to physical or psychological suffering experienced, in the second it is a rational action , a method to achieve a certain goal.

Aggressive behavior is closely related to behaviors such as attack, flight, and defense. The strength of the aggressive behavior can be traced back to the interaction of an activated inner readiness ( aggressiveness ) and an external aggressive situation.

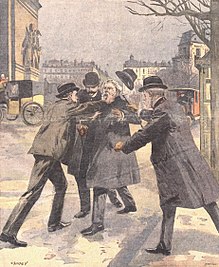

In connection with human behavior, aggression can express itself in verbal ( defamation , insult, accusation), psychological (exclusion) or physical attacks against people, groups of people and things ( damage to property ) or - as in the animal kingdom - in threatening behavior, "comment fights" and ritualized Conflicts, for example in sports, games or at work ( rivalry ).

In international law , in contrast to defense , aggression refers to the first use of force in a dispute between states, peoples and ethnic groups.

Aggression is usually with non-conformist, destructive and destructive behaviors brought connection ; these are (according to Schmidt-Mummendey 1983) in humans mostly characterized by the following factors:

- from the damage ,

- from the intention (intention, directionality),

- from the deviation from the norm .

In humans, “aggressive behavior” is primarily understood to mean direct or indirect physical and / or psychological damage to a living being or damage to an object (according to Merz, F. 1965); regardless of what the ultimate goal of this action is (after Felson, RB 1984). What is important is the intention , regardless of whether there is damage or not (for example if the victim evades at the last second). Often the addition is used that the damaged living being is motivated to avoid the treatment (see also Volenti non fit iniuria - no wrong happens to the consenting person ).

Forms of aggression are:

- open, physical form (towards living beings): hitting , killing , physical threating , auto-aggressive (directed against oneself)

- open, physical form (towards inanimate objects): deliberate contamination, deliberate negligence of objects, damage to property (including vandalism ) and destruction of objects,

- open, verbal or non-verbal form: insulting , mocking , gestures and facial expressions , shouting, raw and deliberately vulgar language styles and manners ,

- hidden form: fantasies ,

- indirect form: damage to property (of objects belonging to the person (s) against whom the aggression is directed), defamation , bullying , harassment , erecting barriers,

- emotional form: as a result of stress , anger , anger , resentment, hatred , envy .

In a broader sense, aggression describes work, competition or a self-confident appearance as an essential form of "attacking". Compared to the narrower definition, these behaviors have nothing to do with harm or injury.

- "Aggression means any behavior that is essentially the opposite of passivity and restraint" (Bach & Goldberg 1974, p. 14, quoted from Nolting 2000, p. 24).

- "Aggression is anything that tries to dissolve an internal tension through activity, initially through muscle power" (Mitscherlich 1969 a, p. 12, quoted from Nolting 2000, p. 24).

- "We define aggression as that disposition and energy inherent in human beings , which are originally and later expressed in the most varied of individual and collective, socially learned and socially mediated forms from self-assertion to cruelty." (Heinelt, 1982.)

Further (motivational) distinguishing features:

- positive (e.g. in sports) vs. negative,

- spontaneous vs. reactive vs. ordered,

- serious vs. playful.

Typical aggression targets are for example:

- asserting one's own wishes and interests that conflict with the wishes of others,

- Get attention from others (ranking),

- Reaction to aggression by others (defense, self-defense ),

- Retaliation for acts of aggression suffered ( revenge ).

Causes and development models

Aggressive human behavior depends on various factors that influence one another:

- cerebral factors: frontal disinhibition ,

- genetic factors: people can be genetically differently aggressive; in most species (the hyenas are an exception ) the males are on average more aggressive than the females,

- Physiological factors: Hormones and neurotransmitters are involved in controlling aggressive behavior, so reduced serotonin and increased testosterone levels are associated with aggressive behavior

- Overall organic factors: Mental states, sensations and motives influence the aggressive behavior, for example pain and other unpleasant states such as high outside temperatures increase the tendency to aggression,

- Group sociological condition: When a hierarchy is formed or when a hierarchy breaks down , all the individuals involved are more aggressive than with a stable hierarchy . In an anonymous group, the members react differently than among confidants,

- socio- ecological factors: high group density or food shortages influence aggressive behavior,

- phylogenetic factors: aggressive behavior has developed differently in different species due to evolution,

- cultural-historical factors: aggressive behavior is culturally reshaped by ritualizations,

- Ontogenetic factors: personal experiences , experiences, frustrations , fears and role models influence aggressive behavior,

- Alcohol consumption weakens the regulating normative social influence ,

- Competitions increase the willingness to aggression among the athletes and the spectators.

Explanatory approaches for aggressive behavior

Aggression describes a variety of behaviors that have in common that a conflict between individuals or groups that was caused by incompatible behavioral goals is not resolved by unilateral or bilateral changes to these behavioral goals, but rather by one party trying to at least try the other Forcing change.

- Drive theory approach: The innate aggression drive pushes for discharge. The best-known representative of the theory is Sigmund Freud .

- Instinct- theoretical approach: The innate instinct of aggression serves to preserve the individual. The best-known representative of the theory is Konrad Lorenz .

- Learning theory approaches:

- Learning on the model : Aggressive behavior is learned based on the role model function of aggressive people who are observed. A well-known proponent of this theory is Albert Bandura .

- Classical conditioning (according to Pavlov ): A neutral environmental stimulus that occurs together with a stimulus that triggers aggression can become the sole trigger for aggression.

- Instrumental conditioning (learning from success): Success is achieved through the use of aggressive behavioral patterns. The success reward makes one act aggressively again in the future. The best known proponent of this theory is Burrhus Frederic Skinner .

- Frustration-aggression hypothesis : Frustration creates aggressive impulses. Well-known representatives are John S. Dollard and Neal E. Miller . Miller extended the hypothesis with the aggression shift by a shift in the aggression goal after inhibition of the original aggression.

- General Aggression Model : The General Aggression Model (GAM) by Craig A. Anderson and Brad J. Bushman summarizes some more specific theories on aggression ( learning on the model , script theory, excitation transfer paradigm, social interaction theory, cognitive neoassociation theory) . It describes how personal and situational factors influence the state. The condition of a person in turn determines how the present situation is assessed and evaluated. From this assessment, a reaction or action that is appropriate from the perspective of the person follows. The chosen action can be thoughtful or thoughtless and aggressive or non-aggressive, depending on the decision. The core elements of the model are knowledge structures, which are formed in the form of concepts, flowcharts and schemes in the person's cognitive system and which represent the knowledge of a situation from which expectations, goals and behavior are derived. With repeated use, these structures solidify and lead to automated processes. With the help of the model, complex influences and causes of aggressive behavior can be identified and explained more precisely.

- The model bio-psycho-social mechanisms of aggression by Klaus choice demonstrates the complex interplay of genetic, epigenetic, neural, psychological and social mechanisms in the realization of aggression.

Influence of genes and neurobiology

There is ample evidence that aggression cannot be traced back to learning alone. Rats that grow up without contact with other rats show aggressive behavior when their territory is threatened. Humans' closest relatives, bonobos and chimpanzees , have very different levels of intraspecific aggression.

Some hormones (e.g. androgens and especially testosterone ) promote an increased tendency to aggressive behavior. During the onset of sexual maturity, it can be observed, especially in male individuals, how the verbal and physical potential for aggression increases (" flailing years "). This in turn is attributed to the changed activity of the genes. These behaviors, which are particularly perceived as destructive by one's own family, can also be directed against oneself (auto-aggressiveness).

The neurotransmitter serotonin appears to play a role in inhibiting aggressive and risky behavior.

According to current knowledge, the underlying neuropsychological mechanism mainly includes activations of the areas of the hypothalamus (VMH, AMH) and the PAG area (periaqueductal gray), which are modulated by activations or innervations of the amygdala and prefrontal areas.

Sigmund Freud and the "death instinct"

From 1905 onwards, Freud formulated the conviction that human aggressiveness was an instinct . Initially, this drive was only seen as a component of human sexuality, but from 1915 on it was also seen as a component of the ego drives. Under the impressions of the First World War, Freud finally began to increasingly formulate aggression as a separate instinct and main representative of the instinct to death or destruction (instinct for destruction). The goal of the so-called death instinct (Thanatos) according to Freud is to destroy units, whereas the eros, or love instinct, wants to create units. These two instincts always run at the same time, so that, for example, we destroy one thing while eating, in order to build ourselves up on the other. It is the task of the instincts to slow each other down, but not to curtail them in order to avoid negative consequences of a one-sided process. The death instinct, the aggression, represents, so to speak, a psychological energy potential that can be used to change. Freud sees a possibility of discharging the death instinct through the defense mechanism of sublimation , whereby the socially outlawed instincts can be redirected into accepted, alternative modes of behavior. According to his "hydraulic model", which has since been refuted, aggressions can build up and later discharge ( catharsis hypothesis). The aggressions can also be shifted to substitute objects, ie discharging in an accepted context or in specifically created therapeutic settings: The child can beat the doll with the wooden spoon and thus discharge its pent-up aggressions towards the mother.

From the perspective of evolutionary biology , Freud's assumptions about the death instinct are problematic insofar as no natural selection mechanism is conceivable to produce an instinct in the course of tribal history that brings individuals closer to death, i.e. reduces their ability to reproduce. On the other hand, it was objected that humans often show culturally learned behaviors instead of species-related, hereditary ones (example " extrauterine spring "), so that the hypothesis of the death instinct, despite its antibiological potential, should not be dismissed out of hand, at least as a way of thinking.

Konrad Lorenz and the "aggression instinct"

In 1963, the behavioral researcher Konrad Lorenz published “ Das so-called Böse ”, a popular science book that was particularly well received by the non-scientific public. In it, Lorenz described an instinct of aggression , which in animals fulfills important biological functions for their survival and reproduction. This instinct is therefore also important for the further development of the species . The positive functions are u. a. the defense of the habitat , the securing of the hierarchy , the securing of scarce resources and the protection of one's own offspring. Lorenz transferred his interpretations of the behavior of animals to humans: Only in this case does the innate instinct of aggression, which from Lorenz's point of view make sense in principle, become a problem, since modern civilization does not allow an appropriate “discharge” of pent-up aggressions. In addition, perpetrators often use weapons against their victims in aggressive acts, which is why the innate inhibition of killing animals (the so-called bite inhibition ) , which he describes in animals, does not prevent acts of excess.

Like Freud, Lorenz advocates “redirecting” the instinct of aggression towards socially accepted action: Sport, science and art are suggested as substitutes for “living out” the “pent up” aggression. In competition with other representatives of these areas of life, you can reduce your aggressions in a socially acceptable form.

While Konrad Lorenz interpreted aggression as a result of constantly bubbling drive energies, other behavioral biologists tend to emphasize the individual motives for aggressive behavior in humans : fear, frustration, obedience, cold calculation, social exploration (“Let's see how far I can go”), gaming behavior u. a. Depending on the prevailing motive, the appropriate way of dealing with the aggressor is then different.

Appetitive aggression

Thomas Elbert , James K. Moran and Maggie Schauer postulate as "appetitive aggression" a biological predisposition that motivates aggressive behavior and allows violence to be exercised with positive affect. If the desire to hunt is also transferred to manhunt, it could even lead to blood rush. The researchers contrast appetitive aggression with reactive aggression, which helps defend against a threat and reduce accompanying negative emotional excitement and anger. In the case of appetitive aggression, on the other hand, there is an intensifying feedback . According to the researchers, a tendency towards pleasure in violence is “by no means a psychopathological peculiarity, but part of human nature, part of the human behavioral repertoire. Morality, culture and the state's monopoly of force are the guardians to regulate the potential for aggression and to direct it into desirable areas ”. According to a study, fighters in armed conflict are more likely to have a lust for violence than civilians, and this is also true of both men and women.

Influence of the environment

Both learning experiences and the situational context influence the strength and the nature of aggressive behavior.

Learning theorists assume that every reinforcement of an action (see instrumental and operant conditioning ) increases its probability of occurrence; They explain aggressive behavior by the fact that one was successful with one's aggression (achieved a goal or received recognition). Only when this reinforcement (this reinforcer ) does not materialize or the undesirable behavior is punished does the aggressive behavior break down (again). This means that behavior that is free of aggression is generally considered possible. Bandura also explains aggression through imitation learning (social learning, model learning, learning from a model): You see how someone else - e.g. B. also the hero in the film - was successful with aggressive behavior, and imitates him because one expects a similar success.

Influence of frustration and fear

According to the frustration-aggression hypothesis , every frustration leads to an increased tendency to aggression. In the classic experiment by Barker, Dembo and Lewin (1941) two groups of children were compared. One was allowed to play with attractive toys immediately, the other could see it, but had to wait a long time for permission to play. Only this group showed aggressive behavior towards the toy.

A further development of the frustration-aggression hypothesis is the cognitive-neoassociationist approach by Berkowitz , which, in contrast to the frustration-aggression hypothesis, makes the following modifying assumptions:

- Frustration does not immediately lead to a need to harm another organism, but this process is mediated by the emotional state of anger.

- In addition to frustration, other forms of aversive stimulation can also trigger negative effects and thus aggression.

- The appearance of negative affects and the willingness to take aggressive action occur in parallel, not sequentially.

The background to these assumptions is an associative network model of human memory: An aversive stimulation as a result of the spread of excitation in the network can trigger thoughts, emotions and motor reactions at the same time. At the same time, the activation of each of these components (e.g. hostile thoughts) can trigger the activation of the other two components. According to Berkowitz, whether an aversive affect leads to avoidance or aggressive actions depends on three factors:

- stable personality traits,

- previous learning experiences (e.g. sensu Bandura),

- from the perception of certain situational aspects, e.g. B. aggressive cues.

For example, frustration does not lead to aggression if the frustrating person is bigger and stronger than the frustrated person, or if the frustrating behavior is judged to be unintended.

The neuroscientist Joachim Bauer explains that fear and aggression are closely related in humans . Mentally unstable people are particularly easily aroused by anything that causes fear. To fear due to threats from the outside world, humiliation and injuries, many people would react with aggression, which is by no means always directed against the cause of the pain, but also hits bystanders with a delay, which sets a spiral of violence in motion. “High capitalism ” and its culture of exclusion (profit-making and competition) thus promote outbreaks of violence by individual individuals.

Common influence of genes and the environment

In his character theory, Erich Fromm tries a combination of the previous considerations. As an investment factor, he assumes basic human needs (security, stimulation, success, freedom), which are more or less well met when a person is socialized, thereby shaping their individual character . This individual character has to deal with the surrounding society (the social character ). If the individual character is sufficiently strong, he can cope better with frustrations or translate them into positive actions. Aggressive role models are not accepted as such and successes are achieved differently.

However, if the individual character is weak - the basic needs were not or only poorly satisfied due to poor upbringing - people also react aggressively in an aggressive environment. Kurt Lewin has also shown that there is a connection between authoritarian leadership style and increased aggression when control is lost. The Milgram experiment can be assessed as evidence for this theory: Man (with a weak individual character) orients himself to the orders of an authority. The supposedly shifted responsibility apparently allows even extremely aggressive actions.

The Austrian-American psychiatrist, psychoanalyst and aggression researcher Friedrich Hacker adopted Konrad Lorenz's theses on the innate, instinctual nature of aggression, but tried - with a kind of squaring the circle - to combine these interpretations of behavior ("biological programming") with behavioristic theses (“socially learned behavior”).

Furthermore, z. For example, the “Berlin School” around the psychoanalyst Günter Ammon assumes that aggression is a so-called “ I function ” or - another term - an “I potential”. An inadequate development of aggression could therefore lead to things not being tackled aggressively - or only inadequately.

Motifs

In their social interactionist theory of aggressive behavior, Tedeschi and Felson name three motives that are central to the decision to adopt aggressive behavior:

- Striving for social power

Whether aggressive behaviors or positive behaviors are used to maintain social control depends e.g. For example, it depends on how important the desired area of influence is, what previous experiences one has had with aggressive and non-aggressive behavior and what alternatives are available. Alternatives to exercising social power through physical superiority are e.g. B. Intelligence, arguments and fluency.

- justice

Aggressive behaviors are primarily used to establish justice when a person believes that severe provocation and injustice has occurred, that there is clear guilt and that there is no effective external punishment body. Another important factor is the relationship between the people involved in the conflict.

- Positive self-expression

Aggressive behaviors are also used to establish or maintain a positive identity. In particular, social pressure, e.g. B. prevails in certain youthful subcultures, in which aggressive behavior is an indicator of masculinity, has an impact on the decision to act aggressively.

Suspected causes of aggression

Some circumstances lead to an intensification of the aggressive tendency in situations where there is aggressive potential:

- Neuropsychiatric Diseases

- Aggression can occur for no apparent reason due to the frontal disinhibition in dementia sufferers. The prevalence varies among the types of dementia: Alzheimer's disease 34%, vascular dementia 72%, Lewy body dementia 71% and frontotemporal dementia 69%.

- Aversive stimuli

- Aversive - i.e. unpleasant - stimuli lead to increased irritability and can cause feelings of anger. In one study, test subjects dipped their hands into water basins in a sham experiment. If the water was very cold or hot, the test subjects reported increased feelings of anger and showed aggressive behavioral tendencies (react irritably to the test leader, etc.). In another study, people were asked to fill out a questionnaire that recorded their aggressiveness. If they filled this out in a very overheated room, they showed increased aggressiveness.

- excitement

- Physiological excitation ( arousal ) reinforces existing behavioral tendencies. In one experiment, test subjects were injected with adrenaline, which led to increased arousal. Afterwards, they were taken to a room with either a very euphoric or very hostile person. If the subjects did not know anything about the adrenaline injection, they behaved to a large extent in the same way as the second person (hostile or aggressive or euphoric). The physiological excitement caused by the adrenaline had intensified the emotional tendency. It is believed that the subjects attributed the excitation to the irritation from the other person.

- If the test subjects knew that they had been injected with adrenaline, their hostile or euphoric feelings did not increase. Although they perceived the physical excitement, they attributed it to the injection.

- Another study showed that people are more likely to be irritated when they exercise. They seem to attribute some of their physical arousal to external irritation rather than exercise.

- Aggressive cues

- If stimuli associated with aggression or violence are present in a situation, these lead to a more rapid outbreak of the aggressive tendencies. In one study, kindergarten children showed more aggressive behavior when they played with toy weapons as opposed to dolls, cars, etc.

- Test subjects who, in a sham study, were supposed to give an alleged learner an electric shock when they answered incorrectly, gave more shocks when guns were hanging on the walls in the experimental room than when tennis rackets were present.

- watch TV

- The learning experiment by Bandura in which children watched an adult with violent dealing with a doll and this mimicked later was replicated with video recordings in which the adult was seen. Even if the children only saw the violence on the screen, they later behaved in a similar way towards the doll.

- Computer games

- Computer games can also have a similar effect to television.

- Self protection

- Aggressive reactions can also be triggered by (supposed) dangerous situations. If you feel threatened, you try to defend yourself, often with psychological or physical violence controlled by the potential for aggression.

- Taking steroids and anabolic steroids

- Anabolic steroids may also lead to increased aggression.

Aggression and information processing

Dodge uses a model to describe six levels of evaluation of social cues that increase the likelihood of aggressive behavior:

- the perception of a potential provocation,

- the interpretation of the observation,

- the definition of your own goals,

- the examination of one's own reaction options,

- the choice of behavior,

- the implementation of the selected behavior.

The process could e.g. For example, it might look like this: “He has illegally stolen my property and my goal is to get it back. The only option is for me to forcibly repeat it to myself as I would have no evidence in court and the thief will not willingly return it to me. So now I will knock him down and repeat my property. "

It has been shown empirically that children who are rated by classmates and teachers as being more aggressive than average tend to interpret the frustration they have experienced as the result of a hostile intention. This so-called hostile attribution bias thus leads to a distortion in the first two processes, as described by Dodge, i.e. a distortion of the encoding and interpretation of the social situation.

Aggression in business

In business life, the term aggression has been assigned a positive meaning since the 1980s , which it also has in American parlance. An "aggressive approach" is expected, especially in sales and advertising. Even within companies, an "aggressive approach" is often considered necessary to achieve goals under the condition of scarce resources. From the employer's point of view, a manager needs a "willingness to fight" and a "killer instinct".

Violence prevention through aggression control

From the knowledge about the development of interpersonal aggression, some approaches to avoid it have been developed. Among the successful strategies include promoting empathy capacity, promoting social skills, good role models, mediation and non-violent communication . A guideline exists for dealing with aggression in the context of the health treatment of patients.

From an ecology perspective

On the other hand, ecologists interpret aggression as a component of “interference”. As such interference fluctuations in population density are caused by social stress at too high population densities ( see population dynamics apply). A high population density creates a higher pressure due to intra-specific competition . Aggression against conspecifics often serves to drive an individual or groups to another area in order to keep the population density in a habitat at a low level and thus the food supply for the individual can be kept high. The relationship between aggression and social behavior often depends on the food available (e.g. in arachnids ). If there is enough food or to protect against predators, social tolerance increases . Many animals show aggressive behavior towards conspecifics as a means of protecting their offspring.

This form of intraspecific aggression is to be distinguished from interspecific aggression is any predators in the food supply as its own, for example.

From a legal perspective

Aggression only becomes relevant under criminal law when it violates a protected legal interest. As a rule, this is mainly the case in the case of bodily harm or, under certain circumstances, property damage . Aggression is unpunished if it is caused by reasons of justification such as self-defense or emergency or the like. justified.

Under international law, aggressive actions have also found their way into the Charter of the United Nations : Aggression is interference in the sovereignty of a state that is not justified. This can be a war of aggression , but also border violations and threats of violence. If an injustice under international law is committed, the person under attack under international law can defend itself against it (however, preventive wars are not permitted). Measures are retaliation (against unfriendly acts) or reprisals (against acts contrary to international law). Both are permissible under international law in the event of aggression.

See also

- Instinctual behavior | Imposing behavior | Infanticide

- Conduct disorder | Dissocial Personality Disorder | Drive renunciation

- mobbing

- “War and Peace” in pre-state societies

literature

Interdisciplinary

- Klaus Wahl : Aggression and Violence. A biological, psychological and social science overview. Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, Heidelberg 2012, ISBN 978-3-8274-3120-2 .

- Klaus Wahl , Melanie Rh. Wahl: Biotic, psychological and social conditions for aggression and violence. In: Birgit Enzmann (Ed.): Handbook Political Violence. Forms - causes - legitimation - limitation. Springer VS, Wiesbaden 2013, ISBN 978-3-531-18081-6 , pp. 15-42.

Behavioral biology

- Desmond Morris : The Naked Monkey. Droemer Knaur, 1968, ISBN 3-426-03224-4 .

- John Paul Scott : Aggression. University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1958.

Neurobiology

- Joachim Bauer : Pain Limit - The Origin of Everyday and Global Violence. Blessing, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-89667-437-1 .

psychology

- Albert Bandura : Aggression. A social-learning theory analysis. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1979, ISBN 3-12-920521-7

- R. Baron, D. Richardson: Human Aggression. Plenum Press, New York 1994, 1997.

- Andreas Dutschmann: The Aggression Coping Program (ABPro). Dgvt-Verlag, Tübingen 2000, ISBN 3-87159-303-6 .

- Ernst Fürntratt : Fear and Instrumental Aggression. (1974). In: HP Nolting (Ed.): Lernfall Aggression. 19th edition. Reinbek 2000.

- HA Euler: The Contribution of Evolutionary Psychology to the Explanation of Violence. In: W. Heitmeyer, H.-G. Soeffner (Ed.): Violence developments, structures, analysis problems. Frankfurt am Main 2004, pp. 411-435.

- Karsten Hartdegen: Aggression and violence in care. Urban & Fischer Verlag, Munich 1996.

- Gottfried Heinelt: Introduction to the psychology of adolescence. A basic course with many practical examples. Freiburg im Breisgau 1982.

- E. Heinemann: Aggression - Understanding and Coping. Berlin / Heidelberg 1996.

- Norbert Kühne : Dealing with aggression. In: Praxisbuch Sozialpädagogik. Volume 6, Bildungsverlag EINS, Cologne 2008, ISBN 978-3-427-75414-5 , pp. 111-137.

- Hans Kunz : Aggression, tenderness and sexuality. (= Works. Volume 4). Huber, Frauenfeld 2004. (new at Schwabe Verlag Basel)

- Siegfried Lamnek, Jens Luedtke, Ralf Ottermann: Tatort family. Domestic violence in a social context. 2nd Edition. VS Verlag, Wiesbaden 2006, ISBN 3-531-15140-1 .

- Stanley Milgram : A behavioral study of obedience. In: Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. Volume 67, pp. 371-378.

- A. Mummendey : Conditions of aggressive behavior. Huber, Bern 1993, ISBN 3-456-30464-1 .

- S. Otten, A. Mummendey: Social psychological theories of aggressive behavior. In: D. Frey, M. Irle (Ed.): Theories of Social Psychology. Volume 2, Verlag Hans Huber, Bern / Göttingen / Toronto / Seattle 2002.

- Hans-Peter Nolting : Aggression learning case. How it arises - how it can be reduced. An introduction. Rowohlt, Reinbek 2005. (New edition, first published in 1978)

- Arno Plack (ed.): The myth of the aggression drive . List, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-471-66531-5 .

- Herbert Selg, Ulrich Mees, Detlef Berg: Psychology of aggressiveness. 2., revised. Edition, Hogrefe-Verlag für Psychologie, Göttingen 1997, ISBN 3-8017-1019-X .

- Frank-M. Staemmler, Rolf Merten (ed.): Aggression, self-assertion, moral courage. Between destructiveness and committed humanity. EHP, Bergisch Gladbach 2006.

Psychiatry and psychoanalysis

- Erich Fromm : Anatomy of human destructiveness . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1977.

- Friedrich Hacker : Aggression. The brutalization of the modern world. Molden Verlag, Vienna 1971.

- Konrad Lorenz : The so-called evil. Munich 1974.

- F. Merz: Aggression and the drive to aggression. (1965). In: HP Nolting (Ed.): Lernfall Aggression. 19th edition. Reinbek near Hamburg 2000.

Jurisprudence

- Friedrich Hacker : Is Man Or Society Failing? Problems of modern criminal psychology. Europa Verlag, Vienna 1964.

- Martin Hummrich: The international criminal offense of aggression. Baden-Baden 2001.

Web links

- Aggression and preventive measures

- Technical Article - Aggression in Children

- Violence in School / Violence Prevention in School. A theoretical consideration with a view to teaching. ( Memento from August 27, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- Keyword: Aggression (Lexicon of Gestalt Therapy)

- Games & exercises to deal with aggression

- Human ethological aspects of aggression (The view of so-called classical comparative behavioral research , PDF; 124 kB)

- From toolmaker to scavenger: ideas about the incarnation as reflected in the history of science Lecture by Dr. Inge Schröder, Anthropological Institute at Christian-Albrechts-University, Kiel; Schröder has been a private lecturer since 2003 and scientific director of the Science Center in Kiel since 2006

- AGGRESSION - Dangerous talk. In: Der Spiegel. No. 27, June 26, 1972.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Klaus Wahl, Melanie Rh. Wahl: Biotic, psychological and social conditions for aggression and violence. In: Birgit Enzmann (Ed.): Handbook Political Violence. Forms - causes - legitimation - limitation. Springer VS, Wiesbaden 2013, ISBN 978-3-531-18081-6 , p. 16f.

- ↑ Klaus Wahl: Aggression and Violence. A biological, psychological and social science overview. Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, Heidelberg 2012, ISBN 978-3-8274-3120-2 , pp. 7-10.

- ↑ Joachim Bauer: Pain Limit: From the Origin of Everyday and Global Violence. 1st edition. Karl Blessing Verlag, 2011, ISBN 978-3-89667-437-1 , p. 34.

- ↑ Joachim Bauer: Pain Limit: From the Origin of Everyday and Global Violence. 1st edition. Karl Blessing Verlag, 2011, ISBN 978-3-89667-437-1 , p. 17.

- ↑ L. Berkowitz: Aggression: Its causes, consequences, and control. McGraw-Hill, New York 1993.

- ^ ER Smith, DM Mackie: Social Psychology. 2nd Edition. Psychology Press, 2000, ISBN 0-86377-587-X , p. 510.

- ↑ G. Stumm, A. Pritz: Dictionary of Psychotherapy. Vienna 2000.

- ↑ Fritz Perls : The ego, hunger and aggression. 1944/1946, Stuttgart 1978.

- ↑ Desmond Morris: The Naked Monkey. Droemer Knaur Verlag, 1968.

- ^ ER Smith, DM Mackie: Social Psychology. 2nd Edition. Psychology Press, 2000, ISBN 0-86377-587-X , p. 504.

- ^ ER Smith, DM Mackie: Social Psychology. 2nd Edition. Psychology Press, 2000, ISBN 0-86377-587-X , pp. 507ff.

- ^ E. Aronson , TD Wilson, RM Akert: Social Psychology. 6th edition. Pearson Studium, 2008, ISBN 978-3-8273-7359-5 , pp.

- ^ M. Wilson, M. Daly: Competitiveness, Risk Taking, and Violence: The Young Male Syndrome. In: Ethology and Sociobiology. 6, 1985, pp. 59-73.

- ↑ A. Patterson: Hostility catharsis: A quasi-naturalistic experiment. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association, 1974.

- ↑ This definition of aggression is based on: Lexicon of Biology. Herder-Verlag, Freiburg 1983.

- ↑ for more information see: psychology.iastate.edu (PDF; 195 kB) : Craig A. Anderson, Brad J. Bushman: Human Aggression. In: Annu. Rev. Psychol. Volume 53, 2002, pp. 27-51.

- ^ Aggression and violence. A biological, psychological and social science overview. Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, Heidelberg 2009. New edition 2012. ISBN 978-3-8274-3120-2

- ↑ cf. also I. Needham et al .: Preface. Violence in the Health Sector. Kavanah, Amsterdam 2016, p. 5. ISBN 978-90-5740-150-3 ; J. Nau, N. Oud, G. Walter: Scientific basic theories of aggression and violence. In: J. Nau, G. Walter, N. Oud (eds.): Aggression, violence and aggression management. 2nd edition, Bern: Hogrefe 2019, pp. 63–75, ISBN 978-3-456-85845-6

- ↑ So Alexander Mitscherlich in his inaugural lecture in Frankfurt in 1968, in: Alexander Mitscherlich: The idea of peace and human aggressiveness. (= Library Suhrkamp. Volume 233). Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt 1969, ISBN 3-518-01233-9 .

- ↑ Thomas Elbert, James K. Moran, Maggie Schauer: Lust for violence: appetitive aggression as part of human nature . In: Neuroforum . May 16, 2017, doi : 10.1515 / nf-2016 to 0056 ( degruyter.com [accessed on 26 October 2019]).

- ↑ Danie Meyer Parlapanis, Roland Weierstall, Corina Nandi, Manassé Bambonyé, Thomas Elbertm Anselm Crombach: appetitive aggression in Women: Comparing Male and Female War Combatants . In: Frontiers in Psychology . January 5, 2016, doi : 10.3389 / fpsyg.2015.01972 ( frontiersin.org [accessed October 26, 2019]).

- ↑ J. Dollard et al .: Frustration and Aggression. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT 1939.

- ↑ L. Berkowitz: Frustration-aggression hypothesis: Examination and reformulation. In: Psychological Bulletin. 106, 1989, pp. 59-73.

- ↑ How fear turns into aggression: “Our fear system has no school leaving certificate”. Joachim Bauer in conversation with Julius Stucke. In: www.deutschlandfunkkultur.de. January 2, 2019, accessed October 18, 2019 .

- ↑ Fear makes you bad. In: www.deutschlandfunkkultur.de. April 18, 2011, accessed October 18, 2019 .

- ↑ MJ Chiu, TF Chen, PK Yip, MS Hua, LY Tang: Behavioral and psychologic symptoms in different types of dementia. In: J Formos Med Assoc. 105 (7), Jul 2006, pp. 556-562.

- ↑ Jens Weidner: Aggressive goes further . In: managerSeminare. Issue 94, January 2006.

- ^ Sigrid Quack : Careers in the Glaspalast, female executives in European banks. (PDF; 318 kB). November 1997, ISSN 1011-9523 : “Ultimately, women themselves were held responsible for the unequal representation of women and men in management positions: their socialization was characterized as“ inappropriate ”or“ wrong ”; they were seen as too emotional, not assertive and aggressive enough to be able to fill management positions successfully. "

- ↑ employer. Issue 1/1991.

- ↑ books.google.de: Treatment guideline: Therapeutic measures for aggressive behavior in psychiatry and psychotherapy.

- ↑ Die Welt of July 27, 2011: Aggression is not a basic human instinct

- ^ The time of April 5, 1974: The myth of the aggression instinct