Anatomy of human destructiveness

Anatomy of Human Destructiveness (original The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness ) is the title of an anthropological and social psychological work on the causes of human violence that Erich Fromm published in 1973 in the USA. The German translation was published in 1974.

In the foreword, Fromm describes the study as the first volume of a comprehensive work on psychoanalytic theory. Accordingly, he had already started to write it down over six years earlier, i.e. in 1967, and included numerous knowledge from other areas ( neurophysiology , animal psychology , palaeontology , anthropology ) in the consideration.

The book analyzes Heinrich Himmler , Adolf Hitler and Josef Stalin , among others . In order to better understand Adolf Hitler, Fromm used knowledge from personal conversations with Albert Speer .

The anatomy of human destructiveness is the most extensive work of all of Fromm's writings and is characterized by a wealth of detail. Despite the fact that this is a scientific research paper, like other writings of the author, it is written for everyone to understand. With this book, Fromm became better known in Germany.

content

introduction

The introduction states: The ever-increasing violence and destructiveness around the world drew the attention of experts and the general public to theoretical research into the nature and causes of aggression. Fromm professed a sociobiological point of view there - five years before Edward O. Wilson and Richard Dawkins popularized the term sociobiology . Fromm does not primarily mean genetics, but his attempt to derive the essence of humans and their passions from their anatomical, neurological and physiological foundations as well as from their anthropologically verifiable living conditions.

Fromm begins by pointing out that the book is "the first volume of a comprehensive work on psychoanalytic theory". He notes that he started writing the book “over six years ago” (around 1967) and quickly reached the limits of his own subject, psychoanalysis. Findings from neighboring scientific fields such as B. neurophysiology , animal psychology , paleontology and anthropology are taken into account in order to be able to adequately deal with human destructiveness.

He had to develop and check his own theory against the other findings. According to the preface, there was no theory at that time "which reported on the results of aggression research in all these areas or established connections or even dealt with them in summary form in one special area [...]". The scientific work is therefore strongly interdisciplinary.

The thesis deals with two topics:

- an investigation into the aggression of humans and animals

- a "certain further development" of Freudian psychoanalysis ( neopsychoanalysis )

The book is divided into three main parts with an appendix:

- Part one: instinctivism, behaviorism, psychoanalysis

- Second part: Findings that speak against the theses of instinct and drive researchers

- Third part: The different types of aggression and destructiveness and their respective requirements

- Epilogue: On the ambiguity of hope

- Appendix: Freud's theory of aggression and destruction

terminology

Right at the beginning, Fromm points out that the term aggression is often used too ambiguously. The most diverse phenomena, which have nothing to do with one another in terms of their underlying causes, are associated with the same term. In order to better understand the phenomenon of aggression, he therefore uses a more precise division of the term aggression:

- constructive acts (in the sense of the Latin word origin: “ad gradi” = “to move towards something”), for example assertiveness, self-conquest, playing, etc.

- Acts that are intended to protect (e.g. self-defense in the event of perceived mortal danger)

- Files that are out to destroy themselves

The last two types of aggression are the main subject of the investigation:

- Benign aggression: defensive aggression for mere defense, biologically necessary (also referred to as biologically adaptive ), serves life, "rational", exists in humans and animals

- Malignant aggression: described in the book with destructiveness , cruelty and as biologically non-adaptive , "irrational", only possible in humans

An additional reason for this subdivision is given later:

“The distinction between biologically adaptive and biologically non-adaptive aggression should help us clear up a conceptual confusion that has been evident throughout the discussion of human aggression. Those who explain the frequency and intensity of human aggression by stating that it can be traced back to an innate trait of human nature often force their opponents, who are unwilling to abandon all hope for a more peaceful world, to the extent of the human To play down destructiveness and cruelty. These lawyers of hope often see themselves put on the defensive and forced to take an overly optimistic view of people. If you differentiate between defensive and malicious aggression, you don't have to. [...] "

The author will go into more detail later on in special cases of aggression (e.g. by predators or cannibalism and the like).

“Pseudo-aggression” is also examined; Fromm understands this to mean "aggressive acts that can cause damage without any intention of doing so". This includes self-assertion and skill exercises.

Fromm expressly emphasizes that, in contrast to the behaviorist theory, he deals “with the aggressive impulses regardless of whether they express themselves in an aggressive behavior or not.” His view of war is analogous to this; the factors that make war more likely are of interest here.

Against other aggression theories

Fromm's work challenges the theory of aggression by Konrad Lorenz , from Sigmund Freud's theory of the "death instinct" and against the theory of behaviorists (specifically BF Skinner ), aggression will reflexively learned when and because they bring success. He presents these theories roughly (and fairly selectively); however, he devotes a forty-page appendix to Freud's theory of aggression.

Dealing with psychological experiments

In his scientific investigations, Fromm also deals with known experiments by other psychologists.

Milgram experiment

The Milgram experiment ("Behavioral Study of Obedience") at Yale University from the 1960s included the conformity behavior of test subjects. In summary, the test subjects there administered (in truth fake) electric shocks as "teachers" to a "student". The test persons - the "teachers" - developed massive somatic stress symptoms (sweating, trembling, stuttering ...). Fromm also quotes from the Stanley Milgrams report that some of the test subjects displayed “bizarre” behaviors such as “nervous laughter and smiles” in isolated, extreme forms, as if “they had fun, their victim Subsequently, according to Milgram's report, these participants denied a possible sadistic background to their inappropriate behavior.

Fromm interprets the experiment as follows (besides criticizing the methodology ):

“The most important finding of Milgram's investigation is likely to be one that he himself did not particularly point out: the existence of a conscience in most subjects and their pain that obedience forced them to act contrary to their conscience. While the experiment can therefore be interpreted as new evidence of how easy it is to dehumanize humans, the reactions of the test subjects tend to point to the opposite: to the presence of strong internal forces that find cruel behavior unbearable. "

Fromm is of the opinion that people in general are reluctant to consciously face their conflicts and postpone the latter into the unconscious. This leads to "increased stress, neurotic symptoms or feelings of guilt for the wrong reasons". The setting of the experiment is also criticized . The scientist who cheered the test person on was a special person in the context of his social position; therefore, "it is difficult for the average person to believe that what science commands could be wrong or immoral." The "high degree of obedience" of the test participants can be explained, among other things.

In view of the other reactions, the author regards the disobedience of the rather high proportion of over a third of the test persons as "astonishing - and encouraging". Since the behavior also allows conclusions to be drawn about the personality structure, Fromm questions the accuracy of the observations:

“Unfortunately, the author does not give us any precise data on the number of“ test subjects ”who remained calm throughout the experiment. To understand human behavior it would be most interesting to learn more about them. Apparently they felt little or no reluctance to take on the cruel acts. The next question is why this was so. [...] "

Subsequently, psychopathy and a malicious character are suspected behind it. In conclusion, Fromm notes that "Milgram's experiment [...] illustrates well the difference between the conscious and the unconscious aspects of behavior".

Stanford Prison Experiment

Philip Zimbardo's Stanford prison experiment is also discussed. This also had conformity behavior and human aggression as an object. A prison situation was simulated with test subjects divided into “guards” and “prisoners”. As is well known, the situation escalated in the course of the experiment, which forced the researchers to terminate the experiment prematurely. Fromm interprets the result of the experiment as follows:

“If, despite the overall atmosphere of this mock prison, which according to the concept of the experiment should be degrading and humiliating (which the 'guards' apparently understood immediately), two thirds of the 'guards' did not commit sadistic acts for their personal pleasure, it seems to me the experiment rather to prove that it is not so easy to turn people into sadists with the help of a suitable situation. "

Importance of the unnoticed remained in the experiment difference "whether you look in accordance with the provisions sadistic acts or whether you want to be cruel to other people and it favors place."

Despite the fact that before the start of the experiment all test subjects were officially tested negatively for sadistic tendencies, Fromm states that such character traits are largely unconscious and are very difficult to detect with the conventional tests used at the time. Here he refers to an earlier study by the Frankfurt Institute for Social Research , which had a similar research topic, but was more successful in uncovering unconscious motives.

Furthermore, he again criticizes the artificial setting and some facts that are confusing for the test subjects, such as B. Their initial capture by the real police for no reason. Confusion among the test persons was accepted - although this distorted the procedure and the results of the experiment.

In the context of the subsequent discussion on the practice, a report by Bruno Bettelheim on the experience of a concentration camp was used to point out that “the prisoners' values and convictions actually made a decisive difference in their reaction to the conditions of the concentration camp, which were the same for everyone . ”In this report it turned out that the“ political and religious prisoners ”reacted“ completely differently ”to the inhuman situation there than the“ [un] political, middle-class prisoners ”.

Summary

In general, Fromm mainly criticizes psychological experiments for overlooking subtle, seemingly unimportant signals that can point to the motives behind the behavior. The “in vitro” setting of many experiments also has a distorting effect. He also points out that there is enough knowledge material from reality (“in vivo”), for example with regard to conformity and aggression. He lists some methods and suggestions for improvement in order to "come to an understanding of the character in its deeper layers". He also recalls a warning by Robert Oppenheimer on the relationship between psychology and the (earlier) methods of the natural sciences.

Interdisciplinary investigation

In the second part of the book, Fromm takes a critical look at the theses of instinct and drive researchers. To do this, he uses the scientific findings from neurophysiology , animal experiments , paleontology and anthropology .

Fromm tries to prove that there is no “innate spontaneous, self-driving aggression instinct” in humans.

Neurophysiology

It is emphasized that psychology and neurophysiology are complementary to one another. The status of both sciences at that time is briefly presented. It must be remembered to always look at the brain as a whole. There are no individual responsible nerve centers for many issues (see phrenology ). The thinking organ is organized as a “dual system”; Activation and inhibition are kept in a certain "flowing equilibrium". Outright anger and violence can arise from disturbances in this balance. Fromm also accepts that the disorder of certain parts of the brain, e.g. B. can also bring the brain out of balance through illnesses or experiments and trigger or inhibit aggression. Among other things, he mentions the stimulation of the caudate nucleus of a bull by JMR Delgado . Other researchers such as WR Hess and J. Olds are also named.

In the course of the study, Fromm provides a “general definition” of defensive (“benign”) aggression in animals and humans:

“When looking at the neurophysiological and psychological literature on animal and human aggression, the inevitable conclusion is that the aggressive behavior is a response to any kind of threat to life - or, as I would prefer to say in a more general sense, vital interests of a living being - as an individual and as a member of its kind. '"

This defensive aggression, which he then attributes as "biologically adapted", includes both attack and flight. Both are "neurophysiologically equally integrated" in living beings. Fromm suggests that people's “flight instinct” must be dampened in war situations so that the soldiers do not desert. He suspects: "In fact, from a biological point of view, flight should be more conducive to self-preservation than struggle."

The aggression of predators is a separate category, the peculiarity of which Fromm summarizes after a brief investigation (including the findings of Lorenz ) as follows:

“The [predator] does not show anger, and its behavior should not be confused with fighting behavior, it is purposeful, precisely aligned, and the tension ends when the goal is reached - the food. The predatory instinct is not a defensive instinct as it is common to all animals, but it relates to the acquisition of food and is specific to certain animal species that are morphologically equipped for this task. "

Animal research

The author deals with animal behavior with a focus on aggression. A closer look is introduced again:

- Predator aggression (discussed in the previous section)

- Aggression against animals of your own kind ( intra- specific): There are certainly many threatening gestures and bickering in the animal kingdom. However, in most mammals - especially primates - there is no intention to kill or bloodthirsty behind it. This aggression is only destructive in comparatively few animal species (e.g. rats ). See also comment fight .

- Aggression against animals of other species ( inter- specific): According to the findings of animal researchers, this usually only occurs in self-defense if it is impossible to escape.

According to the author, animals sometimes behave completely differently in captivity than in their natural habitat. Certain species of monkeys in zoos have shown extremely aggressive behavior and the entire species has been assumed to be willing to use violence. Only observations in the great outdoors brought down the clichés. Examples of this are the baboons from the London Zoo and particularly rhesus monkeys ( Macaca mulata ) cited. According to the animal researchers, animals become aggressive:

- when their range of motion is restricted and

- when their social structure is destabilized.

For example, some animals would then be "induced to frenzy and all kinds of unnatural behavior." This is true even if the animals are well (or slightly worse) fed.

Fromm then deals with the transfer of the knowledge to humans. A high population density is not in itself dramatic; only overpopulation in connection with “their lack of real social ties” is problematic. The term anomie coined by Durkheim also appears.

“These examples show that it is not large population densities as such that are responsible for aggression, but rather the social, psychological, cultural and economic conditions that go hand in hand with it. Obviously the overpopulation, that is, population density combined with poverty , causes stress and aggression; [...] "

In the wild, violence occurs only sporadically in the primates closest to humans ( great apes ). Violent “pecking orders” do not exist despite certain hierarchies. Fromm relies on the observations of researchers such as Jane Goodall or Adriaan Kortlandt .

On the basis of the findings of various animal researchers, Fromm shows that the main diet of great apes (such as chimpanzees according to Goodall) consists mainly of vegetable food with "occasional (effectively rarely)" meat consumption. However, this "does not yet make them carnivores and certainly not predators."

In addition, the popular perception of territorial behavior is criticized with the help of animal research. If this behavior was present in a species, the territories of the same species would often overlap. The concept of hierarchy in great apes is also discussed. For human wars, a justification through territorial behavior is doubtful. According to Fromm, there are some indications that humans have an inhibition to killing, “and the act of killing leads to a feeling of guilt.” Using certain techniques (e.g. denying one's humanity to one's opponent) the inhibition to killing can be relaxed.

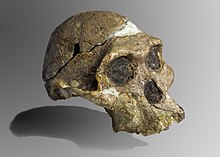

paleontology

In this section, Fromm deals with the ancestors of man. He is convinced that animals of their own kind can recognize one another through their instincts. In humans, however, instinct determination is nowhere near as strong as in animals:

"For him, language, customs, clothing and other criteria that are perceived more mentally than instinctively determine who is a conspecific and who is not, and every group that is somehow different is not assigned to the same genus."

In the event of war, for example, governments tried to deny the enemy humanity in order to provoke defensive aggression.

Then the author tries to differentiate the human species from the predators with the help of the findings of paleontology regarding aggressiveness.

anthropology

Here the main focus is on the scientific research of other peoples and cultures. According to SL Washburn, humanity has so far spent 99% of its time as hunters and gatherers . Supported by the studies of other researchers, primitive hunters and gatherers are examined more closely.

At the beginning of the section, Fromm contrasts the popular stereotypes (also among academics) of the “cruel hunter” with scientific findings. On the basis of observations of existing primitive hunters and gatherers - emphasized with reservation - conclusions are made about the prehistoric times. At this point, Fromm argues that today's man hardly differs neurophysiologically from the prehistoric man to be examined; for this reason, the influences on “personality and social organization” can be examined.

According to the modern observations of existing hunters, the hunt is not rooted in destructiveness and the lust for killing. At this point u. a. Turnbull quotes that the “act of hunting is by no means carried out in an aggressive manner” and that the hunters known to him are “very friendly people”. Numerous physical, psychological and social skills such as “cooperation and sharing” of people developed through this way of life in the early days or were strongly promoted as a result. Hunting is motivated by the joy of activity, the desire to learn and the joy of skill.

The representation includes further detailed knowledge. The "love of property" is alien to primitive people. Generosity, the lack of a "pecking order" (in contrast to mild forms in some primates) and sharing are common in hunting and gathering societies. For different activities there would be different "leaders" within the hierarchy (if at all, then only rudimentary), depending on the situation, whose authority is based on their actual knowledge and skills. In most of these law firms, disputes are mostly settled bloodlessly (with sports competitions or even singing duels). The worst punishment is expulsion from the group. Murder only occurs as a punishment in extreme cases. The term “affluent society” in relation to such social groups is also mentioned.

According to the findings, the “art of warfare” developed “late in human evolution” and was not present among hunters and gatherers. Fromm points out that, according to Lewis Mumford, there are no cave paintings of fights between groups of prehistoric hunters. According to the quoted war researcher Quincy Wright , primitive societies are the most peaceful; only with the increasing degree of civilization does the inclination to war also increase. The more balanced the equilibrium within a law firm, the less likely armed conflicts become.

Fromm then explains the further development of the story with the help of more recent scientific findings. This is followed by an excursus over different epochs, similar to the earlier work The Fear of Freedom . In contrast to this, however, Fromm looks back much further into the past. Thus, with a focus on the changes, the Neolithic and the urban revolutions occur. In addition, u. a. based on the historical excavation site Çatal Hüyük and the Enuma Elis, the thesis of a previously existing “central role of the mother” was established.

Analysis of thirty “primitive” tribes

→ See also: Section “War and Peace” in pre-state societies of the article hunters and gatherers .

Fromm attempted to analyze thirty indigenous (he spoke of "primitive"), still existing tribes with regard to the aspect of "aggressiveness versus peacefulness". He bases his research on the work of Ruth Benedict , Margaret Mead , George P. Murdock and Colin Turnbull, among others . Fromm is expressly "not about statistical, but about qualitative determinations". The investigations were "not carried out selectively for or against the aggression [...]".

The societies were divided into "three clearly distinguishable systems (A, B and C)" based on their social character :

| system | Description and ethnic groups according to Fromm (today common names in brackets) |

|---|---|

| System A - Life-Affirming Societies | “Ideals, customs and institutions” are primarily aimed at “maintaining and growing life in all its forms”. Men and women are equal or at least women are not being exploited. Egoism resigns in favor of cooperation. According to Fromm, belonging to this category is independent of material wealth. |

| the Zuñi Pueblo Indians , the Mountain Arapeshen , the Batonga , the Aranda ( Arrernte ), the Semang , the Toda , the Polar Eskimos ( Inughuit ) and the Mbutu ( Mbuti Pygmies ) | |

| System B - Non-Destructive Aggressive Societies | Like system A, it is non-destructive; however, aggressiveness and war did occur occasionally. The “friendliness and trust” of System A are not so pronounced here. |

| the East Greenland Eskimos ( Tunumiit ), the Bachiga , the Ojibwa , the Ifugao , the Manus , the Samoans, the Dakota , the Maori , the Tasmanians , the Kazaks ( Kazakhs ), the Aino ( Ainu ), the Crow Indians ( Absarokee ), the Inca and the Hottentots ( Khoikhoi ) | |

| System C - Destructive Societies | These societies have a “very distinctive structure” which is permeated “by interpersonal violence, lust for destruction, aggression and cruelty”. |

| the Dobu , the Kwakiutl , the Haida , the Aztecs , the Witoto and the Ganda |

Fromm names the Hopi Indians and the Iroquois as other societies analyzed .

Subsequently, one representative each of the systems A ( Zuñi Indians), B ( Manus ) and C ( Dobu ) is described in detail.

Fromm concludes with the following findings:

- The "instinctivistic interpretation of the human drive to destroy" is "not tenable"

- The differences between the societies are so massive that aggressiveness cannot be an innate passion

- Destructiveness is "not an isolated factor, but [...] part of a character syndrome [...]".

With regard to occurring destructiveness (e.g. human sacrifice) and cannibalism, ritual or religious motives are made responsible and investigated.

Causes of war

This subchapter, which is central to Fromm's argument, stands exactly between his considerations on benign and malicious aggression, i.e. actual destructiveness. War falls into the category of "instrumental aggression". The written history of mankind shows, Freud and Fromm agreed, that wars are waged because of realistic conflicts of interest and not because of an innate drive :

“The Babylonians, the Greeks and all statesmen up to our time planned their wars for reasons that they considered very realistic, and they considered the pros and cons very carefully, even though they were often wrong in their calculations. Their motives were manifold: the land they wanted to cultivate, riches, slaves , raw materials, markets, expansion - and defense. "

In addition, simple societies have obviously waged war less often and less destructively than civilized societies (→ “War and Peace” in pre-state societies: Erich Fromm ) . If the war were caused by innate destructive impulses, the opposite would be the case. " [H] umanitary tendencies" temporarily reduced the number of wars in the 19th century. Fromm cites a table by Q. Wright from his work A Study of War (1965). According to this, the European powers fought 87 battles in the 16th century, 239 in the 17th century, 781 in the 18th century, and 651 in the 19th century; Between 1900 and 1940 there were 892.

Fromm also examines the First World War more closely. On both sides there were economic and political war aims. Both sides had to appeal to a sense of self-defense and freedom in order to motivate their populations to engage in war. According to Fromm, "the government propaganda itself at the beginning of the war" was defensive in color, but that was to change later. In Germany in 1914 there was only collective enthusiasm for war for a few months, which was completely absent in 1939, when the Second World War broke out . In 1917 and 1918 there were massive mutinies by war-weary soldiers in Russia, France and Germany, which ultimately even led to a revolution in Russia and Germany . All of this would be completely inexplicable assuming an innate war or aggression instinct. That something like a drive could be the cause of the First World War is decidedly rejected by the author:

“To assume that this war came about because the French, German, British and Russian people needed an outlet for their aggressions would be a mistake and only serve to divert attention from the people and social conditions that make up one of the greatest Slaughter of world history were responsible. "

Fromm also goes into aspects that make the war acceptable or even attractive for broader sections of the population, e.g. a .: the reverence for authority , the escape from boredom and routine of everyday life, certain forms of comradely solidarity, which stand out positively from the daily competition of peacetime:

“That war has these positive features is a sad comment on our civilization. [...] "

He then mentions ways to reduce the “real factors” (in the social and general sense) that triggered the defensive aggression.

The nature of man

As the premise of his chapter on malignant aggression, Fromm tries to define some psychological characteristics that distinguish humans from other primates . As in previous chapters, the investigation is again shaped by an interdisciplinary approach. The representation serves as a background for his thesis that this also includes the pleasure in killing and destroying, which only occasionally occurs in humans:

“The unique thing about humans is that they can be driven to murder and torment by impulses and that they experience feelings of pleasure. It is the only living being that can become a murderer and destroyer of its own kind without deriving any corresponding biological or economic benefit. "

Fromm comes to the conclusion that human development has separated from that of primates where its determination by instincts has reached a minimum and the “growth of the brain and especially that of the neocortex ” has reached a maximum.

However: According to Fromm, " self- awareness , reason and imagination " have "destroyed the" harmony "that characterizes animal existence":

“He [man] is part of nature , subject to its physical laws and unable to change them, and yet he transcends nature. He is separate from her and yet a part of her. He is homeless and yet chained to the home that he shares with all creatures. [...] Man is the only living being that does not feel at home in nature , that can feel expelled from paradise , the only living being for which its own existence is a problem, which it has to solve and which it does not can escape. [...] "

These “existential contradictions” increase when the person experiences himself “as an individual and not just as a member of a tribe ”. They generate certain existential psychological needs which - according to Fromm - all people have in common. Since each person satisfies them differently, different characters with different passions arise .

In the following section of the chapter, Fromm reports from his work The Sane Society (The Modern Man and His Future , 1955/1960) six existential human needs that can be sources of passions: orientation and devotion , rootedness, unity, the striving to make a difference , Arousal and stimulation (with the counterpart boredom and chronic depression ), the pursuit of a character structure . In the same section, Fromm also tries to substantiate his views with findings from other scientific disciplines.

Spontaneous destructiveness

Fromm differentiates spontaneous outbreaks of destructiveness, that is, spontaneous massacres, as they have occurred in many modern wars, from the destructive character. The former are dormant destructive impulses that are mobilized by sudden traumatic events; the destructive character, on the other hand, is a constantly flowing source of energy.

Spontaneous destructiveness includes forms such as vengeful destructiveness ( blood revenge, etc.; according to Fromm, anchored very differently in different cultures) and ecstatic destructiveness, which manifests itself in trance-like states. Vengeful destructiveness mentions that at high levels of development such as B. the Buddhist or Christian ideal no desire for revenge prevailed. There is also the chronic form of "worship of destructiveness". Fromm portrays the right-wing conservative writer Ernst von Salomon as a clinical case of idolatry on destruction. Also Erwin Kern , who carried out the assassination of Rathenau, is mentioned.

Malicious aggression

Fromm distinguishes between two forms of manifest destructive character: sadism and necrophilia.

sadism

He defines sadism as the desire to inflict physical or psychological pain on a person, to humiliate them, to put them in chains, to force them to unconditional obedience. According to Fromm, non-sexual forms of sadism are much more common than sexual ones. They manifest themselves, for example, in the mistreatment of children, prisoners, slaves, the sick (especially the mentally ill) or dogs.

In a short study, Fromm portrays Josef Stalin as a “clinical case of non-sexual sadism”. He cites several cases narrated by Roi Alexandrovich Medvedev , in which it becomes clear that Stalin enjoyed being the utterly unpredictable master of the life, death and self-respect of his subjects in the persecution and murder of communists. For example, he had the brother of Politburo member Lasar Kaganovich arrested and delighted in the way Kaganovich greeted him with the arrest of his own brother.

As the “essence of sadism”, Fromm derives from these examples the passion for absolute dominion over others. The model of a sadist in this sense is the character of Caligula in Albert Camus ' play of the same name. Fromm draws a bow from this passion to the " anal hoarding character " described by Freud and to the "bureaucratic character". Both have in common that they fear the unpredictable and uncertain in life and therefore develop a strong urge to bring all life around into a fixed order and to keep it under rigid control. Fromm is convinced that sadistic tendencies are to be understood as part of a character syndrome. The "core of sadism" in the general sense is defined by him as follows:

“[...] that the core of sadism is to exercise absolute and unrestricted dominion over a living being, whether it is an animal, a child, a man or a woman. [...] Such control can take on all possible forms and degrees. "

In a detailed, 28-page study, Fromm portrays Heinrich Himmler as a clinical case of anal hoarding sadism . His study is based primarily on the Himmler biography of Bradley F. Smith ( Heinrich Himmler. A Nazi in the Making. Stanford 1971), which focuses on Himmler's youth. As a key point, Fromm picks out an episode in which the 21-year-old had the bride of his older brother Gebhard spied on for allegedly flirting with other men, subjected her to his personal criminal court and finally enforced her banishment from the family. Fromm describes several parallel cases in which the later SS leader had treated subordinate officers very similarly.

necrophilia

→ See also: Section necrophilia according to Erich Fromm of the article necrophilia .

Traditionally, necrophilia is understood as the perverse urge to have sexual acts with corpses or to dismember corpses. Fromm transfers the term to a certain character structure. The first to come up with this idea was the Spanish philosopher Miguel de Unamuno , who in 1936 described the Spanish fascists ' battle cry , “Viva la muerte!” (“Long live death!”), As necrophilic . Fromm calls the opposite of necrophilia biophilia (love for the living). Fromm bases his views on observations from criminology and psychoanalytic practice.

He describes six necrophilic dreams of various people (including a dream by Albert Speer in which Hitler mechanically lays an endless series of wreaths on war memorials - Fromm interprets the dream as a biophilic person's dream about a necrophile). What is noticeable about necrophiles, according to Fromm, is a preference for bad smells - originally for the smell of rotting or rotting meat. The necrophilic language predominantly uses words related to destruction, excrement and toilets. On the basis of such observations, Fromm and M. Maccoby developed an interpretive questionnaire and came to the conclusion that biophilic and necrophilic tendencies are measurable and strongly correlated with political and social attitudes. In the case of a predominance of necrophilic tendencies in a person, according to Fromm, this person then has a necrophilic character .

Following up on Lewis Mumford , Fromm developed the thesis that necrophilia in recent times has often been closely associated with the idolization of technology . As evidence, he quotes in detail from the Manifesto of Futurism , which the Italian fascist Filippo Tommaso Marinetti wrote in 1909 - in it the lines:

"[...] a howling car [...] is more beautiful than the Nike of Samothrace ... [...] there is only beauty in combat. A work without an aggressive character cannot be a masterpiece. […] We want to glorify war - this only hygiene in the world -, militarism, patriotism, the destructive act of the anarchists, the beautiful ideas for which one dies, and the contempt for women. [...] "

In the following, Fromm makes all sorts of references to bomb warfare, nuclear warfare and the construction of robots. He postulates a new type of character, the cybernetic character or monocerebral human being . With this new type, the alienation is so advanced that he no longer has a full affective knowledge of what he is doing. Everything is only perceived intellectually ("monocerebral"), that is, with the intellect . Feelings and affects would be dead and raw. Using the bomber pilots of the Second World War, an attempt is made to demonstrate this development:

“That their actions resulted in many thousands, and sometimes hundreds of thousands, being killed, burned and maimed, they knew of course intellectually, but they hardly got it emotionally; as paradoxical as it may sound, it was none of their personal concern. "

In his hypothesis on incest and the Oedipus complex , Fromm tries to trace the phenomenon of necrophilia back to the traditional categories of Sigmund Freud's psychoanalysis. His thesis is: Men who did not manage to develop an emotional or erotic relationship with their mother as a child, in extreme cases, become autistic . In less extreme cases this could become a root of necrophilia: You are not erotically attracted to the living mother or living women resembling the mother, but rather to the mother as an abstract symbol (for home, blood, race, etc.) or by the mother as the potential murderer of her children. In this way an incestuous bond with death and destruction can develop.

In conclusion, Fromm discusses the parallels between his pair of opposites biophilia - necrophilia and Freud's pair of opposites life instinct - death instinct (Eros-Thanatos). The opposite of necrophilia is defined as follows:

“Biophilia is the passionate love for life and all living things; it is the desire to encourage growth, whether it is a person, a plant, an idea or a social group. "

While the late Freud regarded the life and death instincts as equally important principles, Fromm sees biophilia as a “biologically normal impulse”, while necrophilia, on the other hand, is a “psychopathological phenomenon”, a “result of inhibited growth, a mental cripple”. Most people, according to Fromm, have both biophilic and necrophilic tendencies, with the former usually predominating. He suggests researching the distribution of character structures (e.g. of biophilic and necrophilic tendencies) in the population using methods similar to those used by opinion polls .

Adolf Hitler

Probably the best-known chapter of Fromm's work is the Adolf Hitler study , a clinical case of necrophilia . Fromm relied on the following works about Hitler's childhood and youth (with a focus on the first):

- Bradley F. Smith: Adolf Hitler. His Family, Childhood and Youth. Stanford 1967

- Werner Maser: Adolf Hitler. Legend, myth, reality. Munich 1971

- August Kubizek : Adolf Hitler, my childhood friend. Graz 1953

Ultimately, however, he found no evidence in the reports on Hitler's childhood for what he had called an incestuous connection to death and destruction in his theoretical hypothesis. However, there are numerous indications that Hitler as a child and adolescent never overcame his childish narcissism and preferred to live in a fantasy world than B. to make an effort for secondary school. He failed in secondary school and at the age of 15 was only interested in war games with other, mostly younger boys, in which he could play the leader; he did not develop productive personal interests. He indulged his passion for Karl May novels as Chancellor of the Reich.

His failure in secondary school, as well as later in the entrance examination to the Vienna Art Academy, was solely attributed to Hitler's allegedly hostile people, to whom he swore the most implacable revenge. It was impossible for him to see his own part in it, especially his laziness. He continued to be financed by his mother and lived as a dandy into the day until the money ran out and he slipped into homelessness. Only now, in dire straits, did he settle for a job, painting and selling art postcards. In the homeless shelter he discovered his only real talent, demagogy .

In the further course of this biographical study, Fromm tries to prove that Hitler not only acted destructively, but that he was driven by a destructive character. Fromm found many indications of this in the memoirs of Albert Speer , in the above-mentioned biography of Werner Maser , in the work of Percy Ernst Schramm on Hitler as a military leader (1965) and in Hitler's table talks (published in 1965 by H. Picker) - for example his frequently expressed ones Considerations of destroying certain cities, including the so-called Nero order handed down by Speer . Further details that Fromm lists are Hitler's paranoid fear of syphilis , his hatred of Jews as foreigners and the threat he made in January 1942 that the German people would have to disappear if they were not ready to stand up for their self-assertion.

Ernst Hanfstaengl narrated a bizarre scene from around 1925: He had suggested that Hitler visit London , and he had mentioned King Henry VIII . Hitler agreed, stating that he would like to see the place where two of Henry VIII's wives had been "exterminated" from the scaffold. Finally, the notorious dullness and sterility of his monologues, which he used to give to guests. In all of this, Hitler was a accomplished liar and actor who always knew how to hide his destructiveness from the audience, to adapt his voice and his demeanor to the respective audience.

Fromm also examines other aspects of Hitler's personality: his extreme narcissism, his almost amicable relationship with Albert Speer, his coldness and compassion, his relationships with women, his (little-known) sex life , his greatest talent, the ability to impress other people, which supposedly emanated from his cold, glittering eyes, his acting talent, his real and faked tantrums, his unusual memory, his conversational talent, his cultural and artistic preferences, and finally his amiable, polite, almost shy demeanor, which Fromm values as a camouflage layer , as a mask . Fromm also classifies his love for his dogs here.

Fromm discusses the obvious contradiction between Hitler's cult of willpower and his actual weakness of will and his poor sense of reality. Fromm sums up: Hitler was a gambler; he has played with the lives of all Germans as well as with his own life. Although he probably had psychotic, perhaps schizophrenic, traits, he was probably not a “madman”, so he did not suffer from psychosis or paranoia .

epilogue

In his epilogue , Fromm emphasizes that, as he has shown, sadism and necrophilia are not innate, that is, they could be greatly reduced if the current socio-economic conditions were replaced by others that are conducive to the full development of real human needs and abilities. He criticizes both the optimists, who believed in the dogma of constant "progress", and the pessimists: Anyone who wants to prove the wickedness of man will readily find approval, because he offers everyone an alibi for their own sins ... He defines his own position as that of a rational belief in the ability of humans to free themselves from the apparently fatal web of circumstances that they themselves have created.

expenditure

- Erich Fromm: The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness. Holt Rinehart & Winston, New York 1973.

- Erich Fromm: Anatomy of human destructiveness. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1974, ISBN 3-421-01686-0 .

- Erich Fromm: Anatomy of human destructiveness . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1977, ISBN 3-499-17052-3 .

reception

The distinctly interdisciplinary approach in Fromm's work made its reception in the scientific literature difficult. It was different with the interdisciplinary feminist researchers: American feminists like Mary Daly attacked e.g. B. Fromm's concept of necrophilia, especially the alleged connection between the deification of technology and contempt for women, which Fromm had shown using the example of Marinetti's Futuristic Manifesto .

The American anthropologist David Shapiro and the American biologist Evelyn Fox Keller took up Fromm's definition of non-sexual sadism. Sadism, according to Shapiro, is a special expression for the extreme contempt for weakness and vulnerability.

The German historian Wolfgang Ruge cited in his 1990 analysis of Stalinism approvingly Fromm's Stalin diagnosis as a “clinical case of non-sexual sadism”, referring to Stalin's dealings with Nikolai Bukharin in 1938. The British historian Alan Bullock attacked in 1991 in his double biography of Hitler and Stalin Fromm's thesis that both dictators were narcissistically fixated.

In her criticism of Edmund Burke's philosophical investigation into the origin of our ideas of the sublime and the beautiful, the German art historian Gerlinde Volland transferred Fromm's sadism theory and its categories of necrophilia and biophilia to Burke's dualism of the male principle of the "sublime" and the female principle of the "beautiful".

criticism

In his work Aggression - The Brutalization of Our World , the American psychologist Friedrich Hacker from Vienna criticizes Fromm's distinction between “benign (defensive)” and “malicious (sadistic, necrophilic) aggression” and accuses Fromm of black and white painting. The problem, according to Hacker, is precisely aggressive acts that are judged by the agent to be constructive, but by the person concerned as destructive. In Fromm, too, it ultimately remains unclear how biologically developed instincts relate to human character passions.

See also

literature

- Erich Fromm: Anatomy of human destructiveness . Translated from the English by Liselotte and Ernst Mickel. Rowohlt-Verlag, Hamburg, 25th edition, November 2015. ISBN 978-3-499-17052-2 .

- Siegmar Gassert: Individual and society in relation to reflection . In: Basler Nationalzeitung . December 21, 1974 ( review as PDF file; 25 kB; 3 pages ( memento of September 28, 2007 in the Internet Archive ))

Web links

- Winfried Mohr: On the psychologization of the question of war and peace. In: mondamo.de. Private website, July 1, 2006, archived from the original on January 9, 2011 ; Retrieved on July 12, 2014 (original text probably from 2003).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 9 ff. ( Preface )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 11 ( foreword ): “I thank Albert Speer, who contributed a lot, both verbally and in writing, to enriching my image of Hitler.” In the chapter on Hitler there are footnotes with “A. Speer, personal communication ”.

- ^ Rainer Funk: Erich Fromm - Love for Life: A Pictorial Biography , Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt GmbH, Stuttgart, ISBN 3-421-05279-4 . Chapter 7, p. 161: “[…] Albert Speer, with whom Fromm met repeatedly and had conversations about Hitler; [...] "

- ^ Erich Fromm and Rainer Funk : Erich Fromm Complete Edition, Volume I: Analytical Social Psychology ; Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich, 1999. ISBN 3-421-05280-8 . Reference: Introduction by the editor - On the life and work of Erich Fromm , page XXXIII.

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 9 ff. ( Preface ); esp. p. 12: "This research was partly supported by the [...] of the National Institute of Mental Health ."

- ↑ E. Fromm and R. Funk: Erich Fromm Complete Edition , Volume I: Page XLI. There: “Fromm's English is easy to read and uncomplicated in grammar and style. [...] "

- ↑ E. Fromm and R. Funk: Erich Fromm Complete Edition , Volume I: Page XXXIII

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 9 ( foreword )

- ↑ E. Fromm: Anatomy of human destructiveness , foreword , p. 9.

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 9 ( foreword )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 23 ( Introduction - The instincts and human passions ): “The term psychoanalysis is not used here in the sense of the classical Freudian theory, but in the sense of a certain further development. [...] "

- ↑ E. Fromm: Anatomy of human destructiveness , table of contents, p. 3 ff.

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 13 f. ( Terminology )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 13 ff. ( Terminology )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, pp. 210 ff. ( Die Pseudoaggression ); esp. on etymology / "ad gradi": p. 212 ( aggression as self-assertion )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 210 ( Third part: The different types of aggression and destructiveness and their respective requirements , 9. The benign aggression )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 210 ff. ( Die Pseudoaggression )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 210 ( third part: The different types of aggression and destructiveness and their respective requirements , 9. The benign aggression ; in the original italics)

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 240 ( third part - About the causes of the war )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, pp. 64–88 ( on psychological experiments )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 67 ff. ( About psychological experiments )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 69 ( About psychological experiments ); Fromm cites the following study: “Milgram, S. 1963. Behavioral Study of Obedience. Jour. Dec. Soc. Psychol. 67: 371–378 "(Source in: E. Fromm: Anatomie der Menschen Destruktiv , Bibliographie , p. 544)

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 69: Fromm quotes from Milgrams' research report that "[b] ei fourteen of the forty test subjects [...] this nervous laugh and smile could be clearly observed". Three people showed "downright, uncontrollable fits of laughter"; in one case the “inappropriate and uncontrolled behavior” was “so violent and convulsive” that the researchers “had to interrupt the experiment”.

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 72 ( About psychological experiments )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 71 ( About psychological experiments )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 71 ( About psychological experiments )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 71 ( About psychological experiments )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 72 ( About psychological experiments )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 72 ( About psychological experiments )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 72 ( About psychological experiments )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 72 ff. ( About psychological experiments )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 78 ( On psychological experiments , the original in italics)

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 78 ( On psychological experiments ; original in italics)

- ↑ E. Fromm: Anatomy of human destructiveness , about psychological experiments , p. 66 f .: as a footnote. Said investigation in 1932 was held at the University of Frankfurt held and according to footnote was "mid-thirties completed." Compare this to studies on Authority and the Family and the Berlin worker and employee survey .

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 77 ff. ( About psychological experiments )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 82 ff. ( About psychological experiments )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 64 ff. ( About psychological experiments ); Verbatim quote on p. 66

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 65 ( About psychological experiments ). Footnote: “Cf. J. Robert Oppenheimer's lecture (1955) and similar statements by well-known natural scientists. "

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 65: the source is named there: Oppenheimer, JR 1955. Address at the 63rd Annual Meeting of the American Psych. Assoc. Sept. 4, 1955 (p. 545)

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, Part Two , Findings that speak against the theses of instinct and drive researchers , 5th Neurophysiology , p. 109 ff.

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 109 ff. ( The relationship between psychology and neurophysiology )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 112 ff. ( Findings that speak against the theses of instinct and drive researchers , 5th Neurophysiology )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 113 ff. ( The brain as the basis for aggressive behavior )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 114 ( The brain as the basis for aggressive behavior ; the original in italics)

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 116 ( The defensive function of aggression ; the original in italics)

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 117 ( The Defensive Function of Aggression )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 117 ( The "flight" instinct )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 119 ( The behavior of predators and aggression )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 122 ff. ( 6. The behavior of animals )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 123 ( The aggression in captivity )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 123 ff. ( The aggression in captivity )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 125 ( The aggression in captivity )

- ↑ Fromm here quotes Paul Leyhausen on cats : Bibliography , p. 542: "Leyhausen, P. 1956." Behavioral studies on cats " Beih. z. Ztsch. f. Animal psychology. [...] "

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 125 ( The aggression in captivity )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 125 ( human aggression and overpopulation )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 127 ff. ( Human aggression and overpopulation )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 129 ( human aggression and overpopulation )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, pp. 130 ff. ( Aggression in the great outdoors )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 134 f. ( The aggression in the great outdoors )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 135 ff. ( Territorialism and Dominance )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, pp. 141 ff. ( Do humans have an inhibition to kill? )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 144 ff. ( 7th palaeontology , Is man a kind? )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 144 ( Is man a kind )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 143 ( Do humans have an inhibition to kill? )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, pp. 145 ff. ( Is man a predator? )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 149 ff. ( 8th anthropology, "The human being as a hunter" - the anthropological Adam? )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 149 ff. ( "The human being as a hunter" - the anthropological Adam? )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 156 ff. ( The aggression and the primitive hunters )

- ↑ ibid., P. 158 ( The aggression and the primitive hunters )

- ↑ Fromm points out at the same point (p. 158) that none of the discussion participants contradicted Turnbull.

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 154 ff. ( The aggression and the primitive hunters )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, Die Aggression und die primitiven Jäger , p. 160

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 159 ff. ( The aggression and the primitive hunters )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 159 ff. ( The aggression and the primitive hunters )

- ↑ In his writings Fromm calls this “rational authority”.

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 163 f .: Singing duels to resolve "grudges and disputes [...]" among Eskimos.

- ↑ Fromm quotes ER Service here . See bibliography on p. 547: “Service, ER 1966. The Hunters. Eaglewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. "

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 163 ff. ( The aggression and the primitive hunters )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 165 f. ( Primitive hunters - the affluent society? ); Includes arguments from Marshall Sahlins .

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 167 ff. ( The warfare of the primitives )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 157 ( The aggression and the primitive hunters )

- ↑ At the same point on p. 157, Fromm cites a personal reference by the paleoanthropologist Helmuth de Terra as a second source (regarding the lack of depictions of combat in prehistoric cave paintings of hunters).

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 170 f. ( The warfare of the primitives )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, pp. 173 ff .; beginning with the section The Neolithic Revolution

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015; an example of matriarchy under: The Neolithic Revolution , p. 177 ff .; “[...] the central role of the mother in social structure and religion. [...] ".

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 187 f. ( The Urban Revolution )

- ↑ Fromm is aware of the provocation of the term matriarchal and refers in a footnote on p. 178 to the alternative concept of matrix centrism.

- ↑ Fromm refers in the course of his presentation (p. 180 ff.) To the work Das Mutterrecht by Johann Jakob Bachofen .

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 191 ff. ( Analysis of thirty primitive tribes )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 193 (note in the last paragraph of the description of System C )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 190 ( The aggressiveness in primitive cultures )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 191 ff. ( Analysis of thirty primitive tribes )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 191 - footnote 38: “[…] I have not classified the Hopis because their social structure seems too contradictory to me to allow a classification. [...] "

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 202 ff. ( References to destructiveness and cruelty )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, pp. 203 ff. ( References to destructiveness and cruelty )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 236 ( On the causes of the war )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 236 ff. ( On the causes of the war )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 237 ( On the causes of the war )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 237 ( On the causes of the war )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 242 ( On the causes of the war )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 238 ff. ( On the causes of the war )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 238 ( On the causes of the war )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 240 f. ( About the causes of the war )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 241 ( On the causes of the war )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 243 f. ( The conditions for a reduction in defensive aggression )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, pp. 245 ff. ( The malicious aggression: premises - preliminary remarks )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 245 ( preliminary remarks )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 251 f. ( The nature of man )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 253 ( Die Natur des Menschen )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 253 ( Die Natur des Menschen )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 253 ff. ( Human nature )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 259 ff. ( The existential needs of humans and the various passions rooted in their character * )

- ↑ In a footnote to the heading (*), the author points out that "[the] material on the following pages [...] follows on from the discussion of the same topic in a book The Sane Society ".

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 306 ff. ( Vengeful Destructiveness )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 310 ff. ( Ecstatic Destructiveness )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 312 ff. ( The Adoration of Destructiveness )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 316 ff. ( The destructive character: sadism )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 322 ff. ( Jossif Stalin [...] )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 325 ff. ( The essence of sadism )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 326 ( The essence of sadism )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 338 ff. ( Heinrich Himmler [...] )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 366 ff. ( The Malicious Aggression: The Necrophilia )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 387 f. ( Manifesto of Futurism )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 384 ff. ( Necrophilia and the deification of technology )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 389 f. ( Necrophilia and the deification of technology )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 403 ff. ( Hypothesis about incest and the Oedipus complex )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 411 ( The relationship between [...] and biophilia and necrophilia )

- ↑ Fromm, Rowohlt 2015, p. 411 ff. ( The relationship between [...] and biophilia and necrophilia )

- ^ Mary Daly: Gyn / Ecology. A meta-ethic of radical feminism. 5th edition. Verlag Frauenoffensive, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-88104-215-6 , p. 83 (original: Gyn / ecology ).

- ↑ David Shapiro: Autonomy and Rigid Character. 9th edition. Basic Books, New York 1997, ISBN 0-465-00567-5 ; Evelyn Fox Keller : Love, Power and Knowledge. Male or Female Science? Hanser, Munich 1986, ISBN 3-446-14652-0 , p. 110 (original: Reflections on gender and science ).

- ↑ Wolfgang Ruge: Stalinism. A dead end in the labyrinth of history. Deutscher Verlag der Wissenschaften, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-326-00630-6 , p. 99.

- ^ Alan Bullock: Hitler and Stalin. Parallel lives. Siedler, Berlin 1991, ISBN 3-88680-370-8 , pp. 26-27 (original: Hitler & Stalin ).

- ↑ Gerlinde Volland: Male power and female sacrifice. Sexuality and Violence in Goya. Reimer, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-496-01105-X , pp. 24-25 and 29 ff.

- ^ Friedrich Hacker : Aggression. The brutalization of our world. Updated new edition. Econ, Düsseldorf 1985, ISBN 3-430-13737-3 , p. 115 ff. (First publication: 1971).