Māori

The members of the indigenous population of New Zealand are referred to as Māori , written Maori in German / English . Their ancestors, who came from the Pacific island world, were probably the first immigrants to settle in the previously uninhabited New Zealand in several waves from Polynesia in the 13th century, around 300 years before the European seafarers . Their language is called Te Reo Māori . In 2014, the Māori made up 14.9% of the New Zealand population.

importance

The word “ Māori ” is pronounced with an emphasis on the a, the o is spoken very briefly and sometimes hardly audible. The word remains in the plural without s. In the Māori language , the word means "normal" or "natural". In legends and myths, the word denotes mortal people as opposed to ghosts and immortal beings. The word has cognates in many other Polynesian languages, such as the Hawaiian maoli or the Tahitis mā'ohi language , with similar meanings. In the contemporary Māori language, the word also means “original”, “native” or “indigenous”.

In addition to “ Māori ”, the Māori also refer to themselves as Tangata whenua , literally “people of the country”, and hereby emphasize their feeling of solidarity with their country.

Before 1974, the legal definition of a Māori person was determined by their parentage. This was important, for example, in relation to the right to vote. The Māori Affairs Amendment Act 1974 changed this definition to cultural self-determination, which means: Māori is whoever identifies as Māori . In order to receive special funding, for example, it is still necessary to be of Māori origin , at least in parts . However, there is no prescribed minimum proportion of “ Māori blood”. This can certainly lead to discussions; a controversy arose in 2003 over the nomination of Christian Cullen for the New Zealand Māori Rugby Union Team because he only had 1/64 Māori ancestors. In general, the Māori in particular experience their identity as not being genetically determined but as a question of cultural identity.

History of the Māori

Origin of the Māori

New Zealand was one of the last areas on earth to be inhabited by humans. Archaeological and linguistic research has so far led to the assumption that New Zealand was probably settled in several waves, starting from Eastern Polynesia between 800 and 1300 AD. In more recent radiocarbon dating of bones of the Pacific rat , which only came to New Zealand as an accompaniment to humans could be, but only traces that dated after 1280 were found.

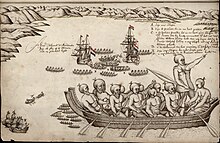

Māori report in their oral traditions of these waves of immigration and describe and name the respective waka , seaworthy outrigger canoes . Various strains of Māori refer to corresponding canoes and call not only their family, but also their canoe when they imagine. The country of origin in Māori mythology is the island of Hawaiki , of which it has not yet been clarified whether it exists, and if so, what name it bears today.

Contact with Europeans before 1840

The colonization of New Zealand by Europeans began comparatively late. The New Zealand historian Michael King describes in his book The Penguin History Of New Zealand the Māori people as "the last great community on earth that lived untouched and unaffected by the outside world". Early European explorers, including Abel Tasman , who reached New Zealand in 1642, or Captain James Cook , whose first visit was in 1769, described encounters with Māori . These early accounts describe the Māori as a fierce and combative warrior people. Martial clashes between the tribes were common at the time, and the vanquished were sometimes enslaved or killed.

From the 1780s onwards, Māori encountered European seals and whalers , and some hired them on their ships. At that time, refugees from the Australian convict colony also had increasing influence on the Māori .

For the year 1830, the number of Pākehā , i.e. Europeans in New Zealand, is estimated to be around 2000. The status of the newcomers at the time varied from slaves to high-ranking advisers, from prison inmates to those who voluntarily turned their backs on European culture and identified themselves as Māori . The latter were of no small number and were called Pākehā Māori . They were well valued by the Māori for their knowledge and technical skills, including in weaponry. Frederick Edward Maning (1811-1883), an early settler and writer, wrote two books about the lives of the settlers and the Pākehā Māori , which are now considered classics of New Zealand literature, even if they do not meet the requirements of historical detail.

But the Europeans also brought diseases with them, some of which had devastating effects on the Māori . If one estimates the population of the Māori in the 18th century at 220,000 to 250,000, one assumes only about 40,000 indigenous people by 1896. Diseases such as tuberculosis , measles , typhus and influenza were able to spread unhindered among them because their immune system was not prepared for the new diseases. But also the acquisition and use of firearms, brought by the Europeans and sold to the Māori in exchange for New Zealand flax , had serious consequences in tribal disputes.

The Musket Wars

The close contact of many tribes to the Europeans and their weapon technology, especially muskets , led to a military imbalance between the tribes and to numerous armed conflicts between various tribes, which went down in New Zealand's history as the musket wars in the middle of the 19th century . Since these battles were sometimes very bloody, the number of Māori decreased considerably, even if the exact number of victims is not known. In addition, the musket wars led to various forced migration movements of individual volatile tribes with shifts in their traditional settlement areas.

With the increasing influence of missionaries , the settlement in the 1830s and a certain lawlessness, the British Crown came under increasing pressure to intervene.

The New Zealand Wars after 1840

The Waitangi Treaty , signed in 1840, stated that the Māori tribes should have unclouded possession of land, forests, fishing grounds, and other taonga . In the course of the years up to 1872 there were several armed conflicts as a result of ambiguities in this treaty. Today the Waitangi Tribunal settles disputes.

Beginning of the boom

The predicted decrease in the Māori population did not occur. Even if a considerable number of Māori and Europeans married and thus mixed, many retained their cultural identity. There are therefore numerous ways of defining who is Māori and who is not. In this respect there is no clearly homogeneous social grouping called Māori .

From the end of the late 19th century there were successful Māori politicians such as James Carroll , Apirana Ngata , Te Rangi Hīroa and Maui Pomare . This group, known as the Young Māori Party , aimed to revive its people from the threats of the 19th century. This did not aim at a demarcation, but rather at the adoption of western knowledge and values like in medicine or education, but on the other hand the unconditional promotion of traditional culture like the arts. Apirana Ngata was a great patron of traditional crafts such as carving or dance, the Kapa Haka . He also developed a land development program and helped many tribes to reclaim their land.

Māori in World War II

The New Zealand government decided to make an exception for Māori , after which they do not like other citizens during World War II for military were canceled, but many Māori volunteered and formed the 28th or Māori - battalion that on Crete , in North Africa and Italy was used . In total, about 17,000 Māori took part in acts of war.

Since the 1960s

Since the 1960s the Māori culture experienced a major boom. The government recognized the Māori as a political force. The Waitangi Tribunal was set up in 1975, an instance where Māori can submit their legal claims arising from the Waitangi Treaty . However, this tribunal can only make recommendations that are not binding on the government. After all, Māori have, for example, successfully asserted basic claims to fishing and forest management. As a result of the tribunal, numerous Iwi compensation payments were also paid, in particular for the land expropriations, which, according to the Māori , only covered 1% to 2.5% of the damage.

In June 2008, the New Zealand government and a Maori collective made up of seven tribes agreed on comprehensive compensation for the indigenous people after more than 20 years of negotiation . The collective, which represents around 100,000 Maori in the center of the country, was awarded 176,000 hectares of commercially used forest area and the income from its management . The government put the total value of the reparations at 500 million New Zealand dollars (about 243 million euros). The treaty made the seven tribes the largest forest owners in New Zealand.

In 1994 the film was Once Were Warriors ( Once Were Warriors ), based on a novel of 1991, a broad audience the plight of Māori -Lebens especially in urban environments. The film had the highest grossing prices during this time and received many international awards. However, some Māori feared that this film would create an image that would make the Māori man appear generally violent .

The Maori language

After the Second World War was in many parts of New Zealand Te Reo Māori , the language of the Māori lost as everyday language. Today, many middle-aged Māori are no longer able to speak this original language. Since the 1970s, many schools have therefore been teaching the culture and language of the Māori , and so-called kōhanga reo (language nests) were created in the kindergartens , in which only Māori is spoken with the children . In 2004 Māori Television started , a state-funded television station that broadcasts its programs in Māori as much as possible , albeit with English subtitles.

Te Reo Māori is the official language in New Zealand today. Therefore, official websites are in both languages, and employees of the public service should at least be able to speak the language, but this has not yet been enforced. The census in 2006 showed that 4.1% of all New Zealanders Te Reo Māori able to speak.

Tradition and handicrafts

Until the arrival of the Europeans, the Māori lived by fishing, hunting for birds and rats, collecting berries, sprouts, seeds and fern roots and growing kūmara (sweet potatoes), taro , hue (bottle gourd) and uwhi (yams), the all brought with them by their ancestors from the northern Pacific islands. The first century after the arrival of the Māori in New Zealand is known as the " moas hunter period", since the large flightless flightless ratite was easy prey for the Māori and it is estimated that it was completely exterminated in the 14th century. After that, fishing and the cultivation of crops became more important.

Tools were made from stones, wood and bones. Important mechanical aids were wedges, runners, pulleys, plows and drill bits operated with cords. The woodworking for the construction of huts and canoes as well as the processing of flax for the decoration of the huts was highly developed, taking into account the simple tools used. Weapons ( mere ) were made from hardwood, strong bones, or stones such as pounamu . For fishing they used spears, fishing lines with hooks as well as nets and pots. The manufacture of mats made from New Zealand flax was of particular importance .

Art found expression in Māori society in the form of oral literature and rhetoric, poetry about song, various performances of music and dance, weaving, wood carving and the making of sculptures from wood and stone. The tattoos of the body, preferably the face, were also an art form in which social rank, status of birth, marriage, authority and personal mark were represented like a signature.

The painting of Māori was not so important before the arrival of Europeans, as it was in the years after. The Wharenui (meeting houses) also differed in number and importance from those we know today and which were made by the respective Māori clans the central focus of their community and are now also supposed to be an expression of their culture. In painting in the pre-European times, only the art of Kowhaiwhai painting, with whose patterns the rafters in the houses, monuments, paddles and the underside of the canoes were painted, had a certain importance.

One of the best-known traditions of the Māori is the haka , a war dance that is now celebrated at festivals and to greet guests and is often performed in front of tourists. The All Blacks have contributed to the popularity of this war dance, who regularly perform the haka before their rugby matches, for the audience and also to show respect for their opponents. Poi , the juggling with balls tied to ropes, is an artistic performance by women who supposedly wanted to use it to win the favor of men.

dress

Originally the Maori dressed in coats of different types and sizes. They were intricately crafted from New Zealand flax or made from dog fur . They kept the heat well, protected against moisture and were very durable. A lot of attention outside of New Zealand was the impressive chief clothing made of feathers and bird skins , which Gottfried Lindauer made known in impressive, lifelike illustrations. Later, individual chiefs, who instead appeared in a black suit, boots and a top hat , tried to dress in the European style.

Traditional religion

In the Māori language there is no independent word for religion, because in their worldview there was no difference between a world in this world and a world beyond. It is astonishing that one can speak of an essentially uniform Polynesian religion in the vast Pacific Ocean of all places , which also includes the traditional beliefs of the Māori.

The first settlers of New Zealand and the mythical ancestors of the common people are called Manahune (for example: the experts of Mana) according to tradition . From them comes an animistic worldview of the (divine) soulfulness of the whole world with various spiritual beings and protective gods (Aiki). The myths of the cultural heroes "Maui" (the rogue) and " Tiki " (the first person), who were significantly involved in the development of life, fertility and human culture (especially fishing), date back to this time .

As in all Polynesian religions, the ancestral cult was of great importance, the conception of man was divided into two parts: body and soul, and the polytheistic , strongly hierarchically structured world of gods reflected the social classes of the pre-state chieftainship in slaves, simple Manahune and Ariki ( high priest and high chief) . In New Zealand, too, an understanding of traditional society is not possible without fundamentally incorporating this transcendent attitude. The central terms here are also mana and tapu . The Māori not only inherited the divine power of mana from his ancestors , but they also had a direct influence on the life of the individual through signs or dreams and at the same time embodied the ancestral land that connected the living with the dead. As with so many skills and arts, in addition to the ariki and the prophets ( tula or taura ) there were various expert experts on religion who were called Tohunga . In Māori art, the Manaia beings stand out, anthropozoomorphic figures with bird and reptile heads. Similar figures can also be found on Easter Island, where the veneration of the bird people is a central part of a cult.

The Māori (→ Rangi and Papa ) conceptions of gods are based on a common Polynesian creation myth , but must also be seen for themselves. In New Zealand, Tane is considered the god of trees and forests, which were believed to have lifted the sky from the earth through the power of their growth. Another (male) god was Tangaroa (Tangaloa, Ta'aroa), the ruler of the sea, who was worshiped on some islands of Polynesia as the supreme creator god and ancestor of the noble families. The tradition of the World Egg is related to it : Tangaroa once slipped away from an egg-shaped structure, with the upper edge of the broken egg shell today forming the sky, the lower edge the earth.

As everywhere in Polynesia, intensive Christian missionary work began shortly after the British expeditions in the 18th century . They were characterized by the strictness with which they prevented any syncretistic attempts to “link” traditional faith and Christianity. Nevertheless, such movements arose in the 19th century, which tried to create "new Polynesian religions" from elements of the traditional and Christian religion, such as Pai Mārire from 1864 or Ratana from 1918. The more Christian Ratana Church is still enjoying today still very popular with the natives, the majority of whom are Christians. The old gods (or the elements they stand for), the religious myths as well as mana and tapu are still trapped in people's thinking despite Christianization.

Māori today

The more than 565,000 people who identify as Māori accounted for 14.6% of New Zealand's population in 2006, with significant regional differences. A Māori is anyone who identifies with the Māori culture , regardless of Māori ancestors or their number. The proportion of people with at least some Māori ancestors is higher at just under 644,000. The number of those who identify as Māori is increasing, however. This is explained with the increased importance of Maorism in New Zealand society, but also with some privileges granted to the Māori such as e . B. Special features in the right to vote and stronger training support.

Even if the situation of the Māori is widely described as good (which it is compared to other indigenous peoples), there are still serious problems within the Māori community itself. The average per capita income of the Māori is well below that of New Zealand as a whole, the Māori are disproportionately represented in the social lower class and 39.5% of all Māori over 15 years of age have no school-leaving certificate compared to 25% of the total population of New Zealand. Over 50 percent of the children are Māori in state welfare .

The life expectancy is still significantly lower than for non- Māori , although it has until now been significantly improved. The average life expectancy in 1900 was 32 years, in 1946 for men 48.8 years and for women 48 years. In 2003 it was 67 years for male Māori and 72 years for female (comparison: non- Māori men 75 and women 81 years).

Well-known personalities among the Māori are the national soccer player and World Cup participant Abby Erceg and the Star Wars actors Temuera Morrison and Daniel Logan . Opera singer Kiri Te Kanawa has a Māori father and an Irish mother.

See also

literature

- Roger Neich : Painted Histories. Early Maori Figurative Painting . Auckland University Press , Auckland 1993, ISBN 1-86940-087-9 (English).

Web links

- Literature on Māori in the catalog of the German National Library

- Historical Māori and Pacific Islands . NZETC,accessed May 3, 2013(list with links to other sources).

- Contemporary Māori and Pacific Islands . NZETC,accessed May 3, 2013(list with links to other sources).

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b J. M. Wilmshurst, AJ Anderson, TFG Higham , TH Worthy : Dating the late prehistoric dispersal of Polynesians to New Zealand using the commensal Pacific rat . In: The National Academy of Sciences (Ed.): PNAS . Volume 105 , No. 22 . Washington June 3, 2008 ( online [accessed May 3, 2013]).

- ^ New Zealand in Profile 2014 . (PDF; (3.5 MB)) Statistics New Zealand , archived from the original on July 5, 2014 ; accessed on May 3, 2019 (English, original website no longer available).

- ^ Neill Atkinson : Adventures in Democracy - A History of the Vote in New Zealand . Otago University Press , Dunedin 2003, ISBN 1-877276-58-8 (English).

- ^ Tracey McIntosh : Maori Identities - Fixed, Fluid, Forced . In: James H. Liu, Tim McCreanor, Tracey McIntosh, Teresia Teaiwa (Eds.): New Zealand Identities - Departures and Destinations . Victoria University Press , Wellington 2005, ISBN 0-86473-517-0 , pp. 45 (English).

- ^ Rugby Union - Uncovering the Maori mystery . BBC Sport , June 5, 2003, accessed May 3, 2013 .

- ^ Trevor Bentley : Pakeha Maori - The Extraordinary Story of the Europeans Who Lived As Maori in Early New Zealand . Penguin Books , Auckland 1999, ISBN 0-14-028540-7 , pp. 132-133 (English).

- ↑ Frederick Edward Maning - July 5, 1812-1883 . New Zealand Electronic Text Collection (NZETC) , accessed May 3, 2013 .

- ^ Frederick Edward Maning : Old New Zealand - History of the War in the North of New Zealand against the Chief Heke . 1863 (English, Online Archive [PDF; 2.0 MB ; accessed on September 24, 2019] compilations of narratives and reports).

- ^ Robert MacDonald : The Maori of Aotearoa-New Zealand . The Minority Rights Group , London 1990, ISBN 0-946690-73-1 , pp. 5 (English).

- ↑ After 150 years of discrimination - Maori receive compensation. N-TV, June 25, 2008, archived from the original on June 26, 2008 ; Retrieved May 3, 2013 .

- ^ QuickStats About Culture and Identity - Languages spoken . Statistics New Zealand , accessed May 3, 2013 .

- ↑ Tanira King : Ahuwhenua - Māori land and agriculture - Changes to Māori agriculture . In: Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand . September 22, 2012, accessed March 22, 2016 .

- ^ Waldemar Stöhr: Lexicon of peoples and cultures . Westermann, Braunschweig 1972, ISBN 3-499-16160-5 , p. 97 f .

- ↑ Christopher Latham : Culture summary: Maori . HRAF Publication Information , New Haven, Connecticut 2009 (English).

- ↑ R. neich : Painted Histories . 1993, p. 1 ff .

- ↑ R. neich : Painted Histories . 1993, p. 16 .

- ^ JJ Weber: Hausschatz der Land- und Völkerkunde - Geographical images from the entire new travel literature. Volume 2, JJ Weber, Leipzig 1896, accessed April 17, 2018.

- ↑ a b Annette Bierbach, Horst Cain: Polynesien. In: Horst Balz et al. (Ed.): Theologische Realenzyklopädie . Volume 27: Politics / Political Science - Journalism / Press. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1997, ISBN 3-11-019098-2 . S.

- ↑ a b c d e Corinna Erckenbrecht: Traditional religions of Oceania. In: Harenberg Lexicon of Religions. Harenberg-Verlagsgruppe, Dortmund 2002, pp. 938–951, accessed on October 14, 2015. (Introduction to the religions of Oceania)

- ↑ Mihály Hoppál : The Book of Shamans. Europe and Asia. Econ Ullstein List, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-550-07557-X , p. 427 f.

- ↑ SA Tokarev : Religion in the History of Nations. Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1968, p. 112 f.

- ^ Hermann Mückler: Mission in Oceania. Facultas, Vienna 2010, ISBN 978-3-7089-0397-2 , pp. 44-46.

- ↑ QuickStats About New Zealand - Ethnic groups, birthplace and languages spoken . Statistics New Zealand , accessed May 3, 2013 .

- ^ QuickStats About New Zealand Education . Statistics New Zealand , accessed May 3, 2013 .

- ↑ Because of state welfare - Maori complain about «modern colonial policy». In: srf.ch . July 31, 2019, accessed July 31, 2019 .

- ↑ Mason Durie : Nga Kahui Pou - Launching Māori futures . Huia Publishers , Wellington 2003, ISBN 1-877283-98-3 , pp. 143 (English).