Maori painting

The Māori -Painting can be divided into two periods, the period of pre-European settlement of New Zealand and the time in which the painting was European influence as an art and crafts. There are only a few examples and testimonies of traditional painting by the Maori indigenous people and it is believed that painting did not have the same status in Māori culture as, for example, carving, the production of sculptures or Tā moko , art of tattooing .

Pre-European painting

With the arrival of European settlers, traders and missionaries in New Zealand in the 19th century, the Māori culture underwent profound changes, which was also clearly reflected in a changed perception and representation of art and handicrafts. Painting, too, was not excluded from this. Painting was not so important in the earlier traditional handicrafts, but this was to change radically from the 19th century.

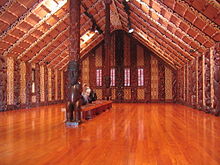

In the pre-European times, the painting trade consisted mainly of the ornate decorating of paddles, the painting and design of the undersides of the waka (canoes), the painting of monoments and the vertical roof beams in the wharenui , the meeting houses of the Māori , who are also their tapu were, a place to be met with respect and reverence. The artistic painting of stones and stone cliffs in caves or grottoes, which is more associated with the technique of drawing, was peculiar to their culture.

The only painting that can be viewed as meaningful in traditional Māori art is that of Kowhaiwhai , a painting of abstract ornamental patterns that are dominant in traditional depictions.

Rock painting

The rock painting can be traced back to the time when the Māori immigrated from Polynesia to New Zealand and still preferred to hunt moas up to the 15th or 16th century. Most of the evidence of this painting is limited to the southern part of the South Island of New Zealand. The predominant motifs are human figures, drawn with lines and filled with color. Stylized Taniwha figures can also be found, as well as simple stylized Koru designs. It is interesting in this context that the finds of rock drawings are all far from the north of New Zealand, from which the settlement of New Zealand essentially originated and was the center of settlement at the beginning.

The few rock carvings that have been found on the North Island are more like relief drawings in which canoes were roughly and erratically carved into the stone. Later, drawings of sailing ships, houses and horses were added to these representations, but these must be counted at the time of the European influence.

Body painting

Painting one's own body was also practiced by the Māori , but it is not an art form in the higher sense for which there were experts or training. Everyone, old or young, man or woman, face or body, was allowed to paint. The first evidence of this is provided by the records of the first Europeans in New Zealand.

Painting on wood

Canoes

An important element in the painting of the Māori was the painting of the war canoes Waka taua , partly for reasons of wood protection and for religious reasons. Separating these, however, is not always possible. The outer shell was preferably kept in a reddish ocher color , as were the carved parts. In northern Iwis , the canoes were also given a black bow and stern . The undersides were given a Puhoro design, usually in black and white colors. The black paint was made from shark oil mixed with charcoal, while the white paint could be made from burnt and ground white clay with shark oil. The Puhoro design is one of numerous Kowhaiwhai designs that were used in the Māori culture.

paddle

When paddles were painted and decorated, they usually got koru designs painted with reddish ocher . Paddles decorated with carvings were only used on festive occasions, whereas the colored paddles were for everyday use. However, undecorated ones were also used. Evidence of the pre-European paddle painting can be seen in the larger museums of the world, as the paddles were easy to receive and transport from the first explorers of New Zealand. A large collection of paddles from Captain James Cook's research trips can be viewed in the British Museum, for example , but also in the Linden Museum in Stuttgart .

Roof beams (rafters) of the Wharenui

Only Koru designs are known of the paintings on the inside roof beams in the meeting houses ( Wharenui ) . The rock paintings from the pre-European period show that these designs were used before the European settlement of New Zealand. The painting in question inside the houses was described somewhat imprecisely by Anderson on Cook's third expedition to the South Seas in February 1777 . The first European travelers, who described the Māori houses on their travels in the 1820s and 1830s , remained vague in their explanations regarding the interior paintings.

A drawing by the missionary Richard Taylor from March 1839 first indicated the existence of the roof beams painted with Kowhaiwhai designs. But preserved beams from older houses from 1842 and 1849 also indicate the painting.

Figurative representations

In addition to some figurative representations in rock painting (see above), there were some early indications that the art of figurative drawing and painting was quite well developed. Proof of this is provided by Cook's notes from 1777, in which he expressed his astonishment when Māori drew a lizard and an eel for him on parchment paper . Further figurative drawings with canoes and scenes, also drawn with ink on parchment paper, followed in the early 19th century. But the influence of European techniques could quickly be seen on the basis of the topics and the development of the representations.

Painting under European influence

Under the influence of European culture, European symbols began to be adopted initially. So initially paintings on meeting houses were created that contained flower patterns, stars or other symbols, whereby windows and door frames were preferably painted with them. People were also portrayed and monsters changed into protectors. In the years 1910 to 1930 even see the pattern that began Tukutuku to paint -Vertäfelung and not to weave more, a development that not prevailed.

In the 20th century, the need to preserve tradition increased, which increased the focus on furnishing the meeting houses as a central location and representation of the Māori culture, a development that began as early as the 19th century when people got away from canoes as identity-creating possession of a tribe towards the meeting house that embodied the tribe, its ancestry and its culture. Accordingly, the painting of the roof beams and rafters was maintained according to what was believed to be traditional and can now be viewed in every meeting house. An illustrated list of 29 different patterns still used today can be found in the work: Maori Art Volume 2 by Augustus Hamilton , published in 1897 .

Contemporary painting

While the traditional and the adapted art of the Māori were initially based on practical and symbolic considerations, this later changed due to the further influence of European culture and oppression, towards the formulation of protest against social and cultural changes and the assertion of one's own culture, of one's own belief and identity. It was a gradually changing social process, but it culminated in the 1960s and 1970s with the emerging nationalism of the Māori , from which painting was no exception.

Initiated in the 1920s by Apirana Ngata , who as Minister of Ministry of Māori Affairs for the language and culture of Māori began, and by Te Rangi Hīroas social (Peter Buck) work, began the search for his own identity. Schools for arts and crafts emerged. In the 1950s and 1960s, the country's universities began to support the movement.

The growing identification of the Māori with their tradition and origin, which also found its echo in art, corresponded to a remarkable exhibition in September 1984 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York . It was the first time that Māori were able to influence the type and design of an exhibition through a committee.

Some contemporary painters of Maori descent:

- Robyn Kahukiwa , born in Sydney in1938, Ngāti Porou, Te Aitanga a Hauiti, Ngati Konohi, Te Whanau a Ruataupare , painting.

- Sandy Adsett , born in Wairoa in 1939 , his pictures have associations with the designs and patterns of the roof beams and rafters of traditional meeting houses.

- Kura Te Waru Rewiri , born 1950 in Kaeo , Whangaroa Harbor , Ngāti Kahu, Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Kauwhata, Ngāti Rang , from 1996 to 2004 lecturer in Māori Visual Arts at Massey University in Palmerston North .

- Shona Rapira Davies , born in Auckland in 1951, Ngati Wai , painting and sculpture.

- Emily Karaka , born in 1952 in the Auckland region, Ngāti Tai ki Tāmaki, Ngati Hine, Ngāpuhi , painting.

- Saffronn Te Ratana , born in New Zealand in 1975, Ngāi Tuhoe , painting.

literature

- Joan Metge : The Maoris of New Zealand Rautahi . Routledge & Kegan Paul , London 1976, ISBN 0-7100-8352-1 (English).

- Roger Neich : Painted Histories . Early Maori Figurative Painting . Auckland University Press , Auckland 1993, ISBN 1-86940-087-9 (English).

- Augustus Hamilton : The Habitations of the New Zealanders . In: Maori Art . Part II . The New Zealand Institute , Wellington 1897 (English, summary of all volumes in a new edition by The Holland Press , London , 1977).

Web links

- History of New Zealand painting - Contemporary Māori art . In: New Zealand History . Ministry for Culture & Heritage , May 9, 2014,accessed March 28, 2016.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b neich : Painted Histories . 1993, p. 16 .

- ↑ Canterbury's Māori Rock Art . Christchurch & Canterbury Tourism , archived from the original on March 28, 2016 ; accessed on April 29, 2019 (English, original website no longer available).

- ↑ a b neich : Painted Histories . 1993, p. 21st f .

- ↑ neich : Painted Histories . 1993, p. 22-25 .

- ↑ neich : Painted Histories . 1993, p. 25-28 .

- ↑ neich : Painted Histories . 1993, p. 59-68 .

- ↑ neich : Painted Histories . 1993, p. 56-58 .

- ↑ neich : Painted Histories . 1993, p. 58 .

- ↑ neich : Painted Histories . 1993, p. 47, 50 .

- ↑ neich : Painted Histories . 1993, p. 119 .

- ↑ neich : Painted Histories . 1993, p. 182-184 .

- ↑ neich : Painted Histories . 1993, p. 162 .

- ^ Metge : The Maoris of New Zealand Rautahi . 1976, p. 275 .

- ↑ neich : Painted Histories . 1993, p. 89 ff .

- ↑ Hamilton : The Habitations of the New Zealanders . In: Maori Art . Part II , 1897, p. 133 (English, 7 illustrated pages with 29 different Kowhaiwhai designs).

- ^ History of New Zealand painting - Contemporary Māori art . In: New Zealand History . Ministry for Culture & Heritage , May 9, 2014, accessed March 28, 2016 .

- ^ Metge : The Maoris of New Zealand Rautahi . 1976, p. 274 .

- ^ Te Maori exhibition opens in New York - September 10, 1984 . In: New Zealand History . Ministry for Culture & Heritage , June 8, 2015, archived from the original on December 30, 2011 ; accessed on April 29, 2019 (English, original website no longer available).

- ↑ Robyn Kahukiwa . Auckland Art Gallery , accessed March 28, 2016 .

- ↑ Jonathan Mane-Wheoki : Sandy Adsett . In: Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand . Ministry for Culture & Heritage , October 22, 2014, accessed April 28, 2019 .

- ↑ Sandy Adsett - Kahungunu . Tairawhiti Museum , accessed March 28, 2016 .

- ↑ Kura Te Waru Rewiri . Auckland Art Gallery , accessed March 28, 2016 .

- ↑ Shona Rapira Davies . Bowen Galleries , accessed March 28, 2016 .

- ↑ Emily Karaka . Auckland Art Gallery , accessed March 28, 2016 .

- ^ Saffronn Te Ratana . Auckland Art Gallery , accessed March 28, 2016 .