ornament

An ornament (from Latin ornare "to decorate, decorate, organize, arm") is a mostly repetitive, often abstract or abstracted pattern with a symbolic function in itself . Ornaments can be found on fabrics , buildings , wallpaper . The term ornament is mistakenly confused with the terms ornamentation or decoration , which describe an agglomeration of decorative elements used in an embellishing function. However, ornaments are often part of or motifs in decorative arts , for example in handicrafts . As a single decorative motif, it is part of the decoration.

Each ornament differs formally clearly from the background pattern and is often delimited by color or by elevation. Ceramic vessels that are decorated with ornaments can already be found in the Stone Age . Ornaments can be formed from floral or fantasy patterns. Flowers and leaf ornaments are often found in churches , cathedrals , cloisters and other structures on pillars or bay windows and on ceilings ( stucco ) or house entrances. Ornaments can also contain abstract shapes, such as traditional clan patterns or tribal symbols, to illustrate the wearer's affiliation. They are particularly common in Islamic art (because of the prohibition of images there ) as arabesques .

As ornamentation refers to the totality of the ornaments in view of its within a certain epoch or for a specific work of art typical forms as well as the art of decorating . The ornamentation of the classic column architecture takes a special position, as it usually follows a tectonic logic. The individual ornaments are understood as reminiscences of constructive elements of early Greek wooden architecture. The appropriate use of the individual ornaments is therefore subject to canonical ties and is a defining theme of early modern architectural theory .

introduction

Ornaments are differentiated from pictures in the classical sense in that their narrative function takes a back seat to the decorative one. They neither create an illusion in terms of time nor depth. Ornaments do not tell a continuous story and are limited to the surface. Nevertheless, ornaments can be naturalistic and sculptural or individual objects such as vases are used ornamentally if they decorate as their main function.

Objective and plastic ornaments contrast with the abstract or stylized ones. The stylization can relate to individual elements or shapes or, as in the arabesque, the direction of movement. The more abstract an ornament is, the stronger the ground appears as an independent pattern. In addition to their degree of abstraction, ornaments differ in their relationship to the wearer. Ornaments can accentuate (rosettes), structure (bands, strips in architecture), fill and frame. The wearer can determine the ornament or, conversely, be dominated by the ornament. Intensity and density also determine the relationship with the wearer.

Ornaments are not only examined as a genre of art , but also in their stylistic development and in the context of human perception . This last-mentioned approach tries to base the study of ornamentation on the findings of psychology. The human fascination with simple geometric elementary forms is explained by the need to choose from the multitude of chaotic visual stimuli. In order to appear aesthetic , ornament according to this approach must also have a certain complexity. Otherwise they will be sorted out as expected.

The history of the style of ornament deals with the development of decorative motifs over time and their design and was founded by Alois Riegl at the end of the 19th century. If a different culture takes over a motif so that it loses or changes its original meaning , or if the carrier medium or production technology changes, for example through mass and automated production, motifs develop further. Different cultures or local currents are in an interplay and influence each other. Sometimes certain forms of an ornament are so typical for an epoch , a place or an individual artist that they are used to determine the origin.

The discussion about ornaments has always been determined by the principle of the decorum , which , when applied to the ornamentation, states whether the location or the design fit. This includes whether an ornament is perceived as cheesy or overloaded. What a society perceives as appropriate depends heavily on its norms. Since ornaments can cover up the perhaps low value or the functionality of their wearer, a sober, so to speak classic ornamentation has been called for in history in the name of natural beauty and grace .

In addition to art, ornament appears in music as a possibly freely improvised ornament or in rhetoric , where it is understood as an exaggeratedly pictorial or rhythmic language. In addition, ornamental elements appear in classical painting , for example in the rhythmic folds of fabric or in the sinuous depiction of figures .

Epoch overview

antiquity

Old Orient

In the Middle East , simple geometric decorations go back as far as 10,000 years, preserved on tools, clay pots or cave walls. Palmette and rosette, spiral and line patterns have been around for several millennia BC. Used for decoration. Two plant motifs that are widespread in ancient Egypt are the lotus in its forms as a leaf, bud or blossom and the papyrus as a blossom. In addition, the ornamental motifs in ancient Egypt also include animals (such as bucrania ), people, characters and geometric patterns. The motifs are lined up, alternated or connected with lines (like spiral lines ). Pine cones and pomegranates are some of the other motifs that were popular even before classical antiquity . The triple spiral and the triskele are motifs from the past. The vortex wheel, a modification of the swastika, is added later.

In architecture, ornaments are mostly used to mark individual structural elements or to frame surfaces. Geometric patterns can also cover entire facades in a planar manner or arranged in registers. Particularly rich decorations can be found in Phrygian architecture, especially on the rock facades of the Midas city . Influences of ancient oriental ornamentation can be found u. a. again in Greek art and architecture.

Classical antiquity

In ancient Greece , numerous new forms of construction were created, especially for temple construction, and assigned to the column orders described in Vitruvius . Particular attention is paid to the design of the capitals . Pictorial representations can be found, mostly as relief, especially in friezes or temple gables.

The ivy leaf appeared relatively early, later the acanthus leaf appeared as an ornament, the latter especially on the Corinthian capital . In addition, more versatile ornaments, such as tendrils and palmettes, developed into their classic forms. Characteristics such as half-palmette and circumscribed palmette emerge, as well as the free, wavy tendril as a connecting element, which later unfolds spatially. The meander in its various variants is particularly widespread in all art genres .

In contrast to ancient Egyptian ornamentation, the motifs are not only arranged strictly at right angles, but can also run diagonally - for example on gables. Ornaments are seen in their relationship to the content, for example as a frame for depictions on vases .

In Hellenism and Roman antiquity , v. a. in the west spatial-naturalistic tendencies in ornamentation; depictions of people and animals ( putti , fantasy creatures or birds) are increasing . On the one hand, late antiquity led to further naturalization and lush surface filling, which v. a. should serve to represent wealth. However, the motifs are often used relatively freely, almost stylized. For example, the unfree acanthus leaf appears, the connecting tendril of which continues at its tip. A more abstract style is developing particularly in the east. Further motifs typical of Roman antiquity are bay leaves , grapes and leaves . The column loses its exclusively load-bearing function and is used ornamentally.

Europe

middle Ages

The Carolingian art took to 800 from only a few centuries ago Late Antiquity the palmette and acanthus . In addition, the animal and braided ribbon decoration from the Celtic and Germanic tradition remained. Both influences were still effective in the Romanesque period . The foliage of the capital decoration made use of the more or less classic acanthus. The architectural ornamentation preferred geometric shapes, such as a tooth cut , serrated band or round arch frieze . In the borders and initials of the book illumination , mainly vegetable elements developed from palmette and acanthus can be found, which - in contrast to the Gothic - are still limited by field separations and frames.

Completely independent of ancient models, the most important type of Gothic ornament develops with tracery . Developed as an architectural element for structuring and structuring large glass window surfaces, these motifs, easily transferable in their linearity, became neatly enriched decorative elements such as carved retables , gilded monstrances or painted book pages. The vertical directionality of the tracery finds a variant in the radially arranged pointed arches of the rose window . In contrast to this geometric and abstract characteristic of the tracery, there is an almost naturalistic plant ornamentation in Gothic . At first it varies on the capital and then displaces the classic acanthus, replacing it with vine leaves and the foliage of native plants. Typical of the Central European foliage ornament in Central Europe are hunched leaves in the 14th century and then, in the late 15th century, thistle-like tendrils. As the entanglements become more complex, and the tracery increases in emotion, the arches are flame-shaped ( " flamboyant bent"), as well as the three fish bladders composite Dreischneuß shows.

- Medieval ornamentation

Early Gothic leaf capital, Heiligenkreuz Abbey , 13th century

Tracery around 1332 on the Katharinenkirche, Oppenheim

Architectural theory and building ornamentation in the Renaissance

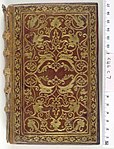

With the rediscovery of Vitruvius' writings in the 15th century, an intensive examination of ancient art and architecture began in Italy, the forms and ornamentation of which soon supplanted medieval forms. The architectural decoration of Roman ruins in particular is studied, copied and distributed in treatises by contemporary architects. Roman wall paintings, especially the grotesques, provide further models for art in architecture . The letterpress , which was also established during this period, is helpful for the spread of ancient designs and ornamentation , the increasing quality of which from the early 16th century also allowed illustrations and (later also colored) plates.

At the center of the new architectural-theoretical discourses were, in addition to the order of columns , also general design principles, which soon went beyond Vitruvian teachings. For Leon Battista Alberti , ornament plays an important role in the definition of the term beauty (pulcritudo). Beauty, according to Alberti, is an ideal state in which nothing can be removed or added to the building without reducing the beauty. Since this state is not achieved in reality, the ornament is applied from the outside of the building in order to underline the advantages of the building and to hide the defects (Alberti: de re aedificatoria, Venice 1485, book VI, chap. 2). The most important application of this dualistic scheme of beauty and ornament is to be found in the theater motif , which in the Renaissance became the most important structuring scheme for building elevations.

16th and 17th centuries

The ornament engravings published as templates for artisans in single sheets and in book form have given a good picture of the development of the ornament style north of the Alps since the early modern era. More than in the Middle Ages, ornaments are now being created as reshapes and replicas of ancient elements such as palmettes , festoons , vases , balusters , candelabra and other architectural elements . The most important plant motif is henceforth the more or less trailing acanthus, which over time has become filigree , sometimes thick-leaved .

The arabesque also awoke to new life in the Renaissance, but unlike the following motifs, it does not mark a type of decoration that can be limited in time, but remains a motif that has been repeatedly taken up in various styles beyond the Baroque period.

In the Italian Renaissance, the grotesque (ornament) experienced a particular bloom, but later also appeared occasionally as large-scale wall decoration throughout Europe. The Mauresque also belongs to this era. The variations of the scrollwork, fittings and cartilage styles that prevailed from the middle of the 16th to the middle of the 17th century can be counted among the grotesques if they retain their fragile, grid-like, floating character, but move away from it, when they appear as a relief or also aim for three-dimensional effects in the area. In detail: The hallmarks of the scrollwork (from 1520) are interlaced and rolled up, inserted and multi-layered tape forms, which are particularly found on frames and cartridges . Derived from this, often also combined with it, the hardware (around 1550-1630) shows itself with its geometrically cut and "riveted" forms as if made of metal. Where this ornament dissolves and begins to move, in the tailing (around 1580-1630), swelling forms emerge, ending in volutes or club-like structures. The amorphous tendency of this ornamental style is further increased in the variants cartilage , dough and auricle style (1570–1660), which show transitions that are barely distinguishable from one another and are also used synonymously. In the second half of the 17th century the acanthus leaves, which now often completely cover the surfaces, regained the upper hand.

- Ornaments of the 16th and 17th centuries

Grotesques

Villa Medici , Studiolo, frescoes around 1577.Fittings and scrollwork

frontispiece , Bishops Bible , London 1568Carved acanthus ornament, Lamspringe Monastery , 1690

20th century

The Viennese avant-garde was the first to formulate severe criticism of ornament in the pre-modern or early modern phase between the turn of the century and the First World War. Above all, Adolf Loos formulated this in his essay Ornament und Verbrechen from 1908 and with his Loos house on Michaelerplatz and Otto Wagner with his postal savings bank designed two buildings that almost completely dispensed with ornamental decoration. There were similar tendencies with Loos friend Arnold Schönberg , who wanted to free classical music from everything redundant and superfluous, and also with the paintings by Egon Schiele , naked and reduced compared to works by Gustav Klimt, which overflowed with golden ornamentation . The criticism of the Viennese avant-garde of ornament, which exerted a great influence on Weimar Modernism and thus the Bauhaus after the First World War, is to be understood especially under the special circumstances of the Austrian capital as the center of a crumbling multi-ethnic state. The superficiality of the representative, magnificent Ringstrasse facades came into the focus of criticism from a large number of young designers, as it was equated with a large number of grievances in the country: with the Catholic double standards prevailing in the country , the nouveau riche bourgeoisie benefiting from industrialization and a outdated empire.

After the Second World War, when, through the emigration of Walter Gropius and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe to America and the re-establishment there as the New Bauhaus, the teachings of the Bauhaus established itself from the USA as an international style , stucco, wallpaper and facade-like appearance all in one Ban was proven and the Ulm School and Swiss typography succeeded in the field of product design and graphics, the ornament almost completely disappeared from the minds of designers as a design element for almost 40 years. Only since postmodernism and finally with the digital revolution has ornament again played a greater role in current design developments.

As an anthropological constant, it has returned to the modern age as a graphic element that can be used across cultures as part of the globalization of communication processes . The protagonists of a revival of ornament in communication design at the beginning of the 21st century are the pixel art- oriented world of eboy , the corporate design of the Berlin director's house in Berlin by Apfel Zet , the Idn magazine designed in Hong Kong by Jonathan NG, and web applications by Yugo Nakamura , Tokyo, or the appearance of the world's leading trade fair Tendence Lifestyle / Messe Frankfurt by Heine / Lenz / Zizka (Frankfurt am Main). In architecture, however, there are still major reservations about using ornament.

Criticism of ornament

Widespread skepticism and rejection of ornament developed in the architecture and product design of modernism . Instead, the formula “ form follows function ” was propagated . Particularly popular was Adolf Loos Ornament und Verbrechen , published in 1908 , in which he castigated the use of ornament and decoration and described it as superfluous.

For the physician Hans Martin Sutermeister , ornament represented a recovery regression: the “magic about ornament” is based “on its affective resp. suggestive effect, which is due to the fact that [...] rhythmic external stimuli tend to have an increasing effect on [the] deep layers of our psyche. ”The ornament can thus be used, similar to rhythmic music, to influence the viewer (or listener).

Quote

"...- all ornaments must serve the facade climber for the best -..."

List of ornaments

Frieze ornaments

| image | Surname | Occurrence, description |

|---|---|---|

|

Egg stick | Ionic order : as a kymation or in the capital, between the volutes. |

|

Running dog | Classic architecture. |

|

meander | Classic architecture. |

|

Bead rod (astragalus) | Ionic order: between column shaft and capital. Endless sequence of one round “pearl” and then two flattened ones. |

Flat and other ornaments

| image | Surname | Occurrence, description |

|---|---|---|

|

Acanthus leaf | Since ancient Greece z. B. in the capitals of Corinthian columns ; Plant ornament ( acanthus ). |

|

arabesque | |

|

Bandelwerk | |

|

tree of Life | |

|

Fittings | |

|

Bukranion | |

|

Feston | |

|

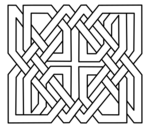

Braided tape | |

|

Fleuron | |

|

grotesque | |

|

Celtic knots | |

|

Cartilage | |

|

Latticework | |

|

labyrinth | |

|

Mauresque | |

|

Millefleurs | |

|

Palmette | |

|

Pine cones | Since Roman antiquity; stylized representation of the fruit of a pine tree , often as a sculpture or hanging . |

|

Rocaille | Renaissance, Rococo; an often exaggerated shell-shaped ornament, often in connection with leaf and tendril decorations. |

|

Scrollwork | Mannerism , early baroque; three-dimensional band shapes, some of which are crossed, pushed through and rolled up. |

|

Tailing | |

|

Dough factory |

literature

- Markus Brüderlin : Ornament and Abstraction - Art of Cultures, Modernity and the Present in Dialog , German and English editions, DuMont Cologne, 2001, ISBN 3770158253 .

- Frank-Lothar Kroll . The ornament in art theory of the 19th century . Georg Olms Verlag, 1987, ISBN 9783487078366 .

- Franz Sales Meyer : Handbook of ornamentation . Seemann, Leipzig 1927, reprint: Seemann, Leipzig 1986. (First edition under the title Systematically organized handbook of ornamentation: For use by draftsmen, architects, schools and tradespeople as well as for studying in general. Seemanns Kunsthandbücher Vol. 1. Seemann, Leipzig 1888 ).

- María Ocón Fernández: Ornament and Modernity. Theory and ornament debate in the German architectural discourse (1850–1930) . Berlin: Dietrich Reimer Verlag, 2004, ISBN 3-496-01284-6 .

- Claudia Weil, Thomas Weil : Ornament in architecture, art and design . Callwey Verlag, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-7667-1619-0 .

- Edgar Lein: Seemanns Lexikon der Ornaments. Origin, development, meaning . EA Seemann Verlag, Leipzig 2006, ISBN 978-3-86502-085-7

- Elke Wagner: Style history of ornaments - from antiquity to everyday culture of the 1980s . iF Design Media, Diplomica Verlag Hamburg 2013, ISBN 978-3-8428-9793-9

- Günter Irmscher: Ornament in Europe 1400–2000 , Cologne 2005, with a thorough bibliography

- Alois Riegl: Questions of style, foundations for a history of ornamentation , Berlin 1893 ( digitized version )

- Günther Binding, Architectural Forms , Darmstadt 1980, 2nd edition Darmstadt 1987, 3rd unchanged edition Darmstadt 1995.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Duden | Ornamentation | Spelling, meaning, definition, origin. Retrieved November 7, 2019 .

- ^ Hans Weigert: Blatt, Blattwerk , in: Reallexikon zur Deutschen Kunstgeschichte , Vol. II (1941), Sp. 834–855; in: RDK Labor (accessed on July 23, 2019)

- ^ Hanno-Walter Kruft: History of the Theory of Architecture, CHBeck-Verlag, Munich 2013, pp. 20-30.

- ↑ Hans Martin Sutermeister . The ornament. In: Of dance, music and other beautiful things: Psychological chats. Hans Huber Verlag , Bern 1944. p. 59.

Web links

- The world's most extensive database for ornamental engravings (MAK, Vienna; UPM, Prague; and Berlin Art Library)

- Geometric ornaments from the architecture of India (by Dr. Bernhard Peter)

- Helmut Pfotenhauer, Classicism as the beginning of modernity? Thoughts on Karl Philipp Moritz and his ornament theory

- Klaus Heitmann: Ornament a crime?

- Ornament: theory and construction

- The power of ornament. The curator Sabine B. Vogel on ornament in contemporary art. Video on the occasion of the exhibition in the Belvedere. (Video by CastYourArt)