Carolingian Renaissance

The Carolingian Renaissance , also known as Carolingian Renovatio or Carolingian Renewal , is the name given to the cultural boom in the early Middle Ages at the time of the early Carolingians , which began at the court of Charlemagne in the 8th century. The renewal affected in particular the education system, the Middle Latin language and literature , the book industry and architecture .

The term introduced by Jean-Jacques Ampère in 1839 and now naturalized was partially questioned in 1924 by the historian Erna Patzelt with reference to continuities from late antiquity to Merovingian and Carolingian culture. The use of the term Renaissance is also controversial because it suggests an analogy to the epoch of Renaissance humanism , which differs significantly from the time of the Carolingian Renaissance. Alternatively, the terms educational reform of Charlemagne or Carolingian renewal (Latin renovatio ) are used.

background

During the Merovingian period there was a decline in ancient urban culture and a general decline in ecclesiastical organization, liturgy , written culture and architecture. The school system had largely come to a standstill since the end of the 5th century. There were reports of priests who did not speak the Latin necessary to pray a correct Our Father . The literature of antiquity, even most of the literature of late Christian antiquity, had largely been forgotten. Not a single classic quote can be found in continental Europe from the end of the 6th to the middle of the 8th century. The same is true of copies by pagan authors of antiquity.

Cultural boom

At the latest since the year 777, Charles gathered many scholars from all over Europe ( Alcuin , Paulinus II of Aquileia , Paulus Diaconus , Theodulf von Orléans ) at his court . This ensured that the court school remained a center of Latin scholarship (theology, historiography, poetry) for decades and that stimuli emanated from there throughout the Franconian Empire .

education

One of the efforts and achievements of the court to collect, maintain and spread education, which can certainly be called a reform program

- the establishment of a court library, which included all accessible works of the sacrae and the saeculares litterae , i.e. the church fathers and the ancient authors

- the development of a new book font, the Carolingian minuscule

- Collecting and copying literature, both in plain text manuscripts, for example Latin classics, and in illuminated splendid furnishings of liturgical books, often based on late ancient Roman and Byzantine traditions ( Utrecht Psalter , Lorsch Gospels , Godescalc Evangelistar , Dagulf Psalter )

- the development and dissemination of a secure text version of the Bible ( Alcuin Bible ), the sacramentary and the Benedictine rule

- Decrees and capitularies in which the churches and monasteries of the empire were advised to take care of the litterae ( e.g. Epistola de litteris colendis or Admonitio generalis in 789)

- the attention to architecture and handicrafts, also here with recourse to the formal language of Roman architecture and Roman art

- Older computist and astronomical texts were received and processed both for the creation of the Carolingian imperial calendar and for the correct determination of the Easter date . Several Carolingian encyclopedias on the calculation of time were created, including the Annalis libellus and the Libri computi .

Several educational researchers of the 19th and early 20th centuries took references in the Admonitio generalis to the teachings of the Lord's Prayer as an opportunity to attribute the establishment of rural and elementary schools to Charlemagne. This was not the case because the Carolingian renaissance was a courtly and monastic educational effort, which, however, was also open to lay people from the upper classes of the population. Cathedral schools in the cities were around from 9/10. Century spread and replaced the monastery schools since the 10th century as leading educational institutions before they in turn had to give the universities first place from the 12th century . Civic, rural and village schools appeared in large numbers only in the late Middle Ages and in the early modern period (around 1450–1600) with greatly varying quality.

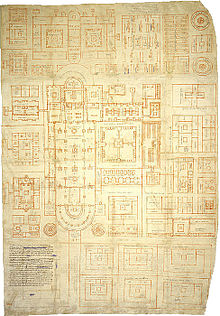

architecture

Both the stately representational architecture and the idea of a monastic ideal architecture in the 9th century ( St. Gallen monastery plan ) show the enormous importance that architecture was once again beginning to be assigned. The Aachen Palatine Chapel is an independent design based on San Vitale in Ravenna (after 526-547), then considered to be the ruling church of Theodoric , and the Sergios and Bakchos Church in Constantinople (completed in 536), which was completed with the Eastern Roman Imperial Palace was connected. According to the written sources, Charlemagne had the Aachen Palatinate built as a second Rome , but also as a counterpart to Constantinople. Obviously, numerous large bronzes were erected for this purpose; he oriented himself on the Lateransplatz in Rome, on which Pope Hadrian I (772–795) had antique bronze sculptures set up.

sculpture

In addition to imported works such as the ancient she-bear (2nd century) and the equestrian statue of Theodoric with accompanying figure (not preserved), new works were created on site in Aachen: eight gallery lattices, four double-leaf bronze doors , and an eagle (not preserved) on the palace rotatable head. The pine cone may only be attributed to the time around 1000. Because of their high quality, these works were thought to be Roman imports for a long time; Only the discovery of a cast furnace and some fittings during excavations on the Katschhof (lost in World War II) could refute this view. It is possible that the Aachen pieces were made by a workshop that previously worked in Saint-Denis .

Charlemagne had the ancient tomb slab of Pope Hadrian I († 795) sent to Rome; the plate is made of black stone ( dinant ), but looks like bronze and obviously mimics the Lex de imperio Vespasiani of 69 AD. The bronze portals from Ingelheim and the seven-armed candlestick by Aniane have not survived.

meaning

Overall, the importance of the Carolingian renewal for the history of Western Europe cannot be overstated. Insofar as the 6th and 7th centuries were actually "dark" centuries , the impetus of Charlemagne and the energy of Alcuin played the role of collecting the scattered legacy of antiquity. What was lost in ancient literature ( book losses in late antiquity ) was lost before the 9th century. However, the educational reform, which was firmly rooted in Christian-patristic teaching, hardly aroused any interest in the profane art of antiquity. For example, until ancient sculpture was "rediscovered", another 600 years had to pass - until the actual renaissance - whereby this "renaissance" of the early Italian humanists was a revaluation of first Roman, then also ancient culture, primarily literature and not a rebirth. For example, Ovid was received a great deal as early as the 12th century , but always from a clerical point of view and conditions.

See also

- List of Carolingian buildings

- Major works of Carolingian book illumination

- Science at the time of Charlemagne

literature

- Dieter Bauer et al. (Ed.): Monasticism - Church - Reign 750–1000 . Sigmaringen 1998.

- Bernhard Bischoff : Medieval studies. Selected essays on writing and literary history , 3 vol., Anton Hiersemann, Stuttgart 1966–1981.

- Arno Borst : The Carolingian calendar reform (MGH writings 46). Hahn, Hanover 1998.

- Arno Borst: The dispute over the Carolingian calendar . (MGH studies and texts 36). Hahn, Hannover 2004, ISBN 3-7752-5736-5 .

- Wolfgang Braunfels (Ed.): Karl the Great. Life's work and afterlife . 4 vols., L. Schwann, Düsseldorf 1967.

- Paul L. Butzer among others: Charlemagne and his aftermath. 1200 years of culture and science in Europe . 2 vols., Brepols, turnhout 1997.

- John J. Contreni: Carolingian Learning. Masters and Manuscripts (Variorum collected Studies Series 363). Aldershot 1992.

- Brigitte English : The Artes Liberales in the Early Middle Ages (5th – 9th centuries). The quadrivium and the computus as indicators for continuity and renewal of the exact sciences between antiquity and the Middle Ages (Sudhofs archive supplement 33). Stuttgart 1994.

- Johannes Fried : The way into history. The origins of Germany up to 1024 . Propylaea History of Germany 1. Ullstein-Propylaea, Frankfurt am Main-Berlin 1994, esp. Pp. 144–161; Pp. 262-324; P. 808ff.

- Norberto Gramaccini, The Carolingian Great Bronzes. Breaks and continuities in material iconography . In: Anzeiger des Germanisches Nationalmuseums 1995, pp. 130–140.

- MM Hildebrandt: The External School in Carolingian Society (Education and Society in the Middle Ages and Renaissance 1). Leiden et al. 1992.

- Jean Hubert et al. (Hrsg.): The art of the Carolingians. From Charlemagne to the end of the 9th century . Beck, Munich 1969.

- Rosamond McKitterick : The Carolingians and the Written Word . Cambridge 1989.

- Rosamond McKitterick : The Uses of Literacy in Early Medieval Europe . Cambridge 1990.

- Rosamund McKitterick (Ed.): Carolingian Culture. Emulation and innovation . Cambridge 1994.

- Willem Lourdaux, D. Verhelst (Ed.): Benedictine Culture 750-1050 (Medievalia Lovaniensia, Series 1, Studia 11). Lions 1983.

- Hubert Mordek : Bibliotheca capitularium regum Francorum manuscripta. Tradition and traditional context of the Franconian rulers' decrees (MGH Aid 15). Munich 1995.

- Erna Patzelt : The Carolingian Renaissance. Contributions to the history of the culture of the early Middle Ages . Österreichischer Schulbuchverlag, Vienna 1924, 2nd edition Graz 1965.

- Pierre Riché : The world of the Carolingians . 2nd edition Stuttgart 1999.

- Ursula Schaefer (Ed.): Writing in the early Middle Ages (ScriptOralia 53). Tubingen 1993.

- Ursula Schaefer (Ed.): Artes in the Middle Ages (Symposium of the Mediävistenverband 7). Berlin 1999.

- Dieter Schaller : Studies on Latin poetry of the early Middle Ages (sources and studies on Latin philology of the Middle Ages 11) . Stuttgart 1995.

- Rudolf Schieffer (Hrsg.): Written culture and realm administration under the Carolingians (treatises of the North Rhine-Westphalian Academy of Sciences 97). Opladen 1996.

- Gangolf Schrimpf (ed.): Fulda monastery in the world of the Carolingians and Ottonians (Fulda studies 7). Josef Knecht, Frankfurt am Main 1996.

- Kerstin Springsfeld: Charlemagne, Alcuin and the calculation of time . In: Reports on the history of science . 27, 1) 2004, pp. 53-66, ISSN 0170-6233 .

- Christoph Stiegemann , Matthias Wemhoff (Ed.): 799 - Art and culture of the Carolingian era. Charles the Great and Pope Leo III. in Paderborn . 3 vols., Mainz 1999. (exhibition catalog)

- Annett Laube-Rosenpflanzer, Lutz Rosenpflanzer: Architecture of the Carolingians: Journey through Europe . Petersberg 2019. ISBN 978-3-7319-0744-2

Web links

- Julia Ricker: Renewed Antiquity. Charlemagne as a promoter of art, education and science , in: Monuments Online 2.2014

Remarks

- ↑ Volker Schupp : Old High German Biblical Poetry and Carolingian Renaissance . In: Freiburger Universitätsblätter , Volume 146, vol. 38, 1999, pp. 17-26

- ^ Erna Patzelt: The Carolingian Renaissance , Vienna 1924

- ↑ Kerstin Springsfeld: Alkuins Influence on Computistics at the Time of Charlemagne , Stuttgart 2002, pp. 91–126

- ↑ Gramaccini pp. 133f.

- ↑ Gramaccini p. 134