San Vitale

The church of San Vitale in Ravenna , probably begun in 537 and consecrated to St. Vitalis in 547 , is one of the most important church buildings of the late antique - early Byzantine period. It combines architectural forms from the Eastern Roman Empire with building techniques typical of Italy at the time. It was created in a time of upheaval when the Eastern Roman Emperor Justinian I waged war against the Eastern Gothic kingdom in Italy.

Famous as is centrally planned church built especially for their mosaic features in the interior, especially the portraits of Justinian and his wife Theodora in the lower Apsisgewände . Together with the other early church buildings in Ravenna, San Vitale has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1996 . In 1960 she received it from Pope John XXIII. the honorary title of Basilica minor .

Building history

At the site of today's church there was already a small cross-shaped building in the 5th century AD, as excavations from 1911 have shown. It cannot be proven whether this was already used for the veneration of Saint Vitalis. According to Keller, the narthex of the current building is considered the place of the martyrdom of the saint.

The Ravenna chronicler Agnellus reports in the 9th century that the Catholic Bishop Ecclesius, who held his office from 521 to 532, was the founder of the building that can be seen today. This is confirmed by a mosaic in the apse of the church, which Ecclesius presents as the founder of the building. At that time, Ravenna was still the capital of the Ostrogothic kingdom, whose Germanic elite professed Arian Christianity . The population of Ravenna was accordingly divided into an Arian and a Catholic community, each headed by a separate bishop. Agnellus also reports that a banker named Julianus Argentarius financed the construction. Evidence for this can also be found inside the church, where the monogram of Julian appears several times . His name is also used in connection with the financing of other churches in Ravenna, such as B. Sant'Apollinare in Classe . The role of Ecclesius' successor Ursicinus (534-536) in the construction of San Vitale is unknown.

The actual construction work was probably not started until the next bishop, Victor (537 / 38–544 / 45). It is his monogram that the combatant blocks inside the church bear. During the time of his episcopate, the Ostrogothic rule over Ravenna came to an end when the city was captured by Byzantine troops under the command of the general Belisarius in 540 . According to Agnellus, the church was consecrated in 547 under Bishop Maximian (546–556). His portrait can be found on a mosaic in the lower apse wall.

In the 10th century , San Vitale came into the possession of a Benedictine community . Some changes were made to the structure during the Middle Ages. For example, groin vaults were added to the ceilings of the gallery and the gallery . To absorb their thrust, several buttresses were added to the outer structure. In the 16th century the church received a new entrance portal in the east.

architecture

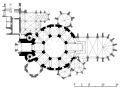

San Vitale was designed as a two-shell niche central building with a set of columns. The core of the building is an octagonal , domed central room. The main entrance to this was originally the narthex connected to the southwest . This is shifted from the axis of the building to the southeast, so that it only touches the octagon at one edge. Of the two apses with which the narthex originally ended, only the northern one remains today. The transition between the narthex and the octagon is formed by two interstitial spaces, each with a stair tower (ø: 5.40 m). be flanked, through which one reaches the galleries.

The core of the central space is also defined as an octagon by eight pillars that support the dome. The space between the pillars is filled with semicircular niches structured by two-column arcades, which also continue in the galleries. The dome, with a diameter of 15.70 m, rests on an octagonal, windowed drum , was built in the lightweight construction typical of Italy from rings of clay tubes , the so-called tubi fittili , and covered on the outside with a pyramid roof. The dome decoration dates from the late 18th century. This central part of the room is surrounded by a slightly lower, two-story corridor.

The chancel is separated from the handling by arcades and covered by a groin vault. The polygonal sheathed apse adjoins it in the northeast . This is flanked by two chapels with a circular floor plan. In the chancel and apse there are also the late antique mosaics, for which San Vitale is known.

The entire church is made of massive brickwork. The long, narrow bricks that were used are similar to those of the other buildings by Julianus Argentarius and are easy to distinguish from the bricks that were used, for example, in the buildings of Galla Placidia or Theodoric .

Mosaics

San Vitale is known, like many of the late antique monuments of Ravenna, for its rich mosaic decoration. This is divided into wall and floor mosaics. The latter originally spread over the entire church space as various ornamental and floral patterns and are rather held in matte earth tones. While they have largely been preserved in the handling, they have meanwhile been largely replaced by a more recent Opus sectile floor in the central dome .

The wall and ceiling mosaics, which were also made while the church was being built, make a significantly different impression. They cover almost the entire area of the altar and apse and impress with their strong colors, with blue, green and gold dominating as background colors. Compared to mosaics of classical antiquity, the representations are composed of relatively large tesserae , with the incarnate being modeled more finely than the background. This, too, is based on the representation convention that emerged in late antiquity, according to which content has priority over form. The overwhelming impression of the mosaics is mainly due to their splendor of colors. In contrast to other representations, which have often lost their color intensity over the centuries, the mosaics consist of color-fast (semi-precious) stones. Real gold leaf was used for the golden tesserae, which was embedded between two layers of glass.

The entrance area to the chancel, the reveal of the triumphal arch, is completely covered with mosaics. They show portrait medallions of Christ, his twelve apostles and Saints Gervasius and Protasius, who were originally venerated in one of the two side chapels of the church and were considered the sons of Saint Vitalis. Most of the figurative representations on the mosaics in the sanctuary refer to the Old Testament . The two lunettes above the pillars north and south of the altar show Abraham entertaining the three pilgrims and sacrificing his son Isaac in the north and Abel and Melchizedek making offerings for God in the north . Both mosaics clearly refer to the Eucharist celebrated below them at the altar of the church. Above the bezels there are two angels each, depicting the life of Moses and the prophets Jeremiah and Isaiah . Above this, next to the window openings in the galleries, there are full-body portraits of the four evangelists with their respective symbolic animals. The top zone is covered with floral patterns, while the ceiling shows a medallion with the Lamb of God carried by four angels . The apse front wall bears, along with another pair of angels, depictions of the heavenly cities of Jerusalem and Bethlehem .

The apse is dominated by the beardless Christ enthroned on a celestial sphere in the apse calotte. The representation on the "celestial sphere", with which the entire universe is meant, is an artistic implementation of the honorary name "Cosmokrator" (world ruler). The title saint Vitalis, to whom Christ is presented with a martyr's crown, and Bishop Ecclesius, who is represented as the founder of the church, are brought to him by two angels .

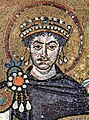

The most famous mosaics of San Vitale, however, are probably the portraits of Justinian and Theodora in the apse, accompanied by their court. Justinian in the north stands in the center of his mosaic field and carries a paten (host bowl) towards the Christ depicted in the apse calotte. He is clearly distinguished from the people around him by his elaborate costume and is characterized as an emperor: he wears a three-row gem-studded diadem and a purple paludamentum with a gold-studded tabula, a rectangular piece of fabric that distinguished high dignitaries at the late Roman court and in a similar form also contributes other people of the two mosaics can be recognized. Noteworthy is also the magnificent Scheibenfibel (orbiculus) with pendilia and Trifolium (three-part piece of jewelry). Another sign of his imperial dignity is the nimbus that surrounds his head. Several dignitaries and his bodyguard follow the emperor. Justinian is preceded by Bishop Ravennas, who is named Maximian by an inscription, and two other clergymen. Maximian wears an alba (white tunic or dalmatic), over it a planeta and a pallium as an archbishop's badge. All men wear special calcei , sandals with caps on the toe and heel that were only worn by the upper class. The technical term for the red imperial sandals is calcei mullei .

In the southern mosaic field, Theodora is shifted slightly to the east from the center. She is clearly identified as an empress by her costume, as well as by her nimbus and the niche behind her. She wears a dalmatic under a purple cloak, a hooded crown with long pendilies and a jeweled collar . In her hands she carries the Eucharistic wine chalice (calix). She is preceded by two dignitaries who resemble those in the mosaic opposite, while a group of ladies-in-waiting follows her. Apart from the imperial couple and the bishop, none of the persons depicted can be identified with absolute certainty, even if some figures are repeatedly attributed to, for example, Belisarius or the mother of Justinian in research. The importance of these mosaics is based u. a. on the fact that they represent one of the few clearly attributable representations of the imperial couple. The facial features in particular seem to have an individual character, although the late antique tendency towards abstraction can still be clearly recognized. As far as height is concerned, it can be assumed that it rather reflects the social rank of the person, as has been common practice since late antiquity. In addition, the two mosaics offer valuable information about the early Byzantine court costume.

It can be considered certain that the mosaics in the apse date from the time of Bishop Victor (537 / 38–544 / 45). Due to the political situation at the time, the depictions of the imperial couple could only have been created after the Byzantines conquered Ravenna in 540. Victor's successor Maximian had the mosaic decoration of the altar area completed and his own portrait inserted into the mosaic field with the portrait of the emperor in place of that of his predecessor. The portrait of the official standing between or behind Justinian and the bishop was also only created during this period.

Abel and Melchizedek

Frescoes

While the design of the altar and apse area goes back to the time San Vitales was created, the pictorial decorations of the central dome area that can be seen today were only created in the modern era. Towards the end of the 18th century, the Benedictine monks commissioned the artist Serafino Barozzi to decorate the church that was entrusted to them. This was soon followed by Jacopo Guarana . The work was completed by Ubaldo Gandolfo , who had previously worked with Barozzi. The frescoes are typical illusionistic paintings . In the top of the dome, Saint Vitalis and Saint Benedict are shown in heaven.

organ

The organ was built in 1967 by the Mascioni organ building company. The instrument has 53 stops on three manuals and a pedal . 15 of these are transmissions and 13 are extensions.

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Coupling: I / II, III / I, III / II, I / P, II / P, III / P; Super-octave coupling (II / II, III / II, III / III, I / P, II / P, II / P) and sub-octave coupling III / II.

classification

The building that is architecturally most closely related to San Vitale is the Sergios and Bakchos Church, built by Justinian I in Constantinople before 536 . Here, too, a domed octagonal central room forms the focal point of the building. Unlike in Ravenna, however, semicircular and rectangular niches alternate between the pillars. As in San Vitale, the handling is also octagonal and, typical for Constantinople, has a gallery. However, this interior structure does not affect the exterior, which has a square basic shape. Overall, San Vitale stands very strongly - stronger than any other Ravenna church - in the Constantinopolitan building tradition. It is possible that Bishop Ecclesius brought the plans for the construction of the church with him to Ravenna after he and Pope John I traveled to the Eastern Roman capital in 525 on behalf of the Ostrogothic King Theodoric .

In turn, San Vitale itself became a role model for Western European architecture. The Aachen Palatine Chapel , built by Charlemagne around 800 , has strong references to the Ravenna building. The Franconian ruler had also brought Ravenna under his control by conquering the Longobard Empire. According to tradition, he had building materials such as B. pillars, from there to Aachen. Charles probably tried to give legitimacy to his own, only recently won empire by referring back to late Roman-Byzantine traditions.

See also

literature

- Irina Andreescu-Treadgold, Warren Treadgold : Procopius and the Imperial Panels of S. Vitale. In: The Art Bulletin. Vol. 79, No. 4, 1997, pp. 708-723, ( jstor.org ).

- Friedrich Wilhelm Deichmann : Ravenna. Capital of the late antique western world. Volume 1: History and Monuments. Steiner, Wiesbaden 1969, pp. 226-256.

- Friedrich Wilhelm Deichmann: Ravenna. Capital of the late antique western world. Volume 2: Commentary. Part 2. Steiner, Wiesbaden 1976, ISBN 3-515-02005-5 , pp. 47-206.

- Gianfranco Malafarina (ed.): La Basilica di San Vitale a Ravenna (= Mirabilia Italiae. Guide. 6). Panini, Modena 2006, ISBN 88-8290-909-3 (Italian and English with numerous illustrations).

- Otto G. von Simson : Sacred Fortress. Byzantine Art and Statecraft in Ravenna. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ 1987, ISBN 0-691-04038-9 , pp. 23-39.

- Jutta Dresken-Weiland : The early Christian mosaics of Ravenna - image and meaning , Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg 2016, ISBN 978-3-7954-3024-5

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Hiltgart L. Keller: Reclam's Lexicon of Saints and Biblical Figures. Legend and representation in the fine arts. 8th, revised edition. Reclam, Stuttgart 1996, ISBN 3-15-010154-9 , p. 569.

- ↑ Jürgen J. Rausch: The dome in Roman architecture. Development, design, construction. In: Architectura. Vol. 15, 1985, ISSN 0044-863X , pp. 117-139, here p. 123.

- ↑ Jürgen J. Rausch: The dome in Roman architecture. Development, design, construction. In: Architectura. Vol. 15, 1985, pp. 117-139, here p. 124.

- ↑ Urs Peschlow : Early Byzantine Architecture. Constantinople and Ravenna. In: Art History Worksheets. 12, 2003, ISSN 1438-8995 , pp. 27-38, here p. 37.

- ^ Heinrich Laag : Small dictionary of early Christian art and archeology (= Reclams Universal Library . No. 8633). Revised and newly illustrated edition, revised and bibliographically supplemented edition. Reclam, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-15-008633-7 , p. 155.

- ↑ Irina Andreescu-Treadgold, Warren Treadgold: Procopius and the Imperial Panels of S. Vitale. In: The Art Bulletin. Vol. 79, No. 4, 1997, pp. 708-723.

- ^ Gerhard Steigerwald: A picture of the mother of the emperor Justinian (527-565) in San Vitale to Ravenna (547). In: Ulrike Lange, Reiner Sörries (ed.): From the Orient to the Rhine. Encounters with Christian Archeology. Peter Poscharsky on his 65th birthday (= Christian Archeology. Vol. 3). Röll, Dettelbach 1997, ISBN 3-927522-47-3 , pp. 123-145.

- ↑ on the history of the origins of the mosaics see: Irina Andreescu-Treadgold, Warren Treadgold: Procopius and the Imperial Panels of S. Vitale. In: The Art Bulletin. Vol. 79, No. 4, 1997, pp. 708-723.

Coordinates: 44 ° 25 ′ 14 " N , 12 ° 11 ′ 46.3" E