St. Gallen monastery plan

The St. Gallen monastery plan is the earliest representation of a monastery district from the Middle Ages and shows the ideal design of a monastery complex from the Carolingian era . It is addressed to Abbot Gozbert of the St. Gallen Monastery , was probably created between 819 and 826 in Reichenau Monastery under Abbot Haito and is in the possession of the St. Gallen Abbey Library . It is kept there under the name Codex 1092 . Only a facsimile was on display until 2018 .

In April 2019, the Abbey Library and the St. Gallen Abbey Archives opened a new exhibition in which visitors can view the valuable, now around 1200-year-old document in the original - but only for a very short time, because the parchment is sensitive to light.

description

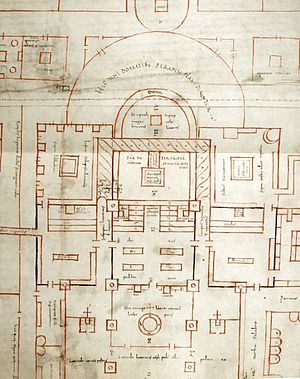

The monastery plan has a size of 112 cm × 77.5 cm and consists of five pieces of parchment sewn together, which are held together with white intestinal threads. Began working with the central part of the plan with church and cloistered , later the canvas was pieced. The type of lettering and the drawing indicate that the additions were made during the work.

Despite some damage from previous folds - the damaged areas were sewn with green silk threads - the plan is well preserved. The red red lead has chipped off only in a few places on the inner edge of the attachments where the plan was folded. The inscriptions are done in a uniform style in brown-black ink. At times the ink has faded, so that here and there difficulties arose in deciphering it.

At the turn of the 12th and 13th centuries, the plan in the northwest corner was damaged. Back then, a monk had used the back of the map to write down the life of Saint Martin . To simplify matters, the plan has been folded according to the columns described. When it turned out that there was not enough space, the monk scratched out the large building in the northwest corner to write the end of his story. In the 19th century, chemical liquids attempted to make the scratched-off areas visible again, but the damage they caused was greater than the benefit. It left bruises and the parts are definitely spoiled.

On April 20, 1949, the plan in the Swiss National Museum was replaced by the canvas on which it had been raised in the 17th or 18th century for reinforcement. As a result, it no longer appears in a dark brown, but much lighter.

content

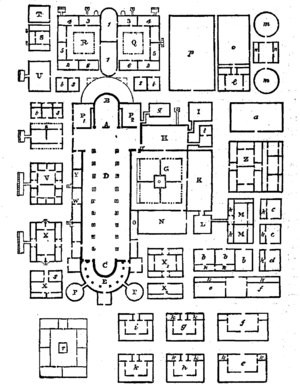

The plan of the monastery shows the ground plans of around fifty buildings, the names and functions of which are described in 333 tituli (inscriptions). The largest and drawn most accurate building of the complex is the monastery church, the scriptorium , sacristy connect an accommodation for guests monks and goal areas, followed by around a square cloister grouped exam , the area of the monks ' dormitory , refectory , latrine, lavatory , Kitchen, bakery and brewery. Furthermore, a guest house, the abbot's palace, hospital and a novice house, which share a double chapel, and numerous commercial buildings and craft businesses as well as gardens, fences, walls and paths are shown. The buildings could accommodate more than 100 monks and around 200 workers and servants.

The plan for the walled gardens contains a rectangular medicinal garden ( herbularius ) with 16 beds and a rectangular kitchen garden ( hortus ) with 18 beds, next to the cemetery designed as an orchard ( boum-gart ). The plants for herbularius and hortus are all also part of the plant list of Capitulare de villis and ten plants of herbularius are also found in Hortulus of Walafrid Strabo.

Interpretations and theses of research

In view of the long and active history of research, various interpretations are in competition today, which so far could not be resolved consistently everywhere. However, a broad consensus could be reached on some points.

Today, the production of the plan in Reichenau Abbey is largely certain, as is a time window between around 819 and around 837 with a focus on the early years, while there is disagreement about an even more precise date. Florian Huber believes he can see a chronogram with the year 819 in the inscription on the goose stable .

An examination of the manuscripts by Bernhard Bischoff , palaeographer and connoisseur of Middle Latin, showed that the plan was inscribed by two scribes and that the inscriptions , written in Alemannic minuscule , come from Reginbert, who was scribe, teacher and librarian in the Reichenau monastery under Abbot Haito . One of the manuscripts in the plan of the monastery matches the manuscript of a Vita of Saint Martin, which was written by Reginbert.

Haito , abbot of the Reichenau monastery , is suspected to be the sender of the plan . As advisor to Charlemagne , he held a high rank, but was also an equal official brother of the St. Gallen abbot. Haito had renounced all dignities in 822 and from then on lived as a monk in Reichenau Monastery, where he died in 835.

In 2002, Angelus A. Häussling suspected the Reichenau monk and abbot Walahfried Strabo (808 / 809-849) to be the “mastermind” of the plan , which would, however, indicate a late dating to 837.

Different standards of the plan are discussed. Florian Huber last calculated the scale 1: 160 in 2002 with good reasons and made the use of the ancient Roman foot ( pes monetalis ) of 29.62 cm long credible.

In 1979 Walter Horn thought the plan was a copy because he couldn't find any traces of drawings. Since the late 1970s, however, more and more traces of marks (blind grooves, shaves) have been found on the parchment.

For what purpose the monastery plan was made is not clear. According to the dedication inscription, the plan was drawn up for Abbot Gozbert , who headed the St. Gallen Monastery from 816 to 837. In 830 Gozbert had the existing monastery church torn down and replaced with a new building, but the church built at that time was not an exact implementation of the monastery plan. Therefore, research sees the monastery plan more as a planning basis, which was made for Abbot Gozbert and the St. Gallen monks, but not implemented in detail. In this way, the St. Gallen references in the plan (altars, Gallus tomb, dedication letter) can be balanced with the archaeological findings that differ from the drawing. Barbara Schedl does not see a binding architectural drawing for the construction in the plan, but a draft as the basis for an independent planning process, which was discussed between the two abbots and builders of Reichenau and St. Gallens, Haito and Gozbert, with the learned staff of both monasteries.

The free-standing towers, which are hardly to be found north of the Alps, and the arrangement of the buildings (the important buildings such as the library, scriptorium, school and abbot's palace are housed in "cool" places) also led to the assumption that the plan was created in the south could be. It is also unclear who Abbot Gozbert was allowed to address in the dedication with dulcissime fili (most beloved son). The text of the dedication reads:

“Haec tibi dulcissime fili cozb (er) te de posicione officinarum paucis exemplata direxi, quibus sollertiam exerceas tua (m), meamq (ue) devotione (m) utcumq (ue) cognoscas, qua tuae bonae voluntari satisfacere me segnem non inveniri satisfacere me segnem non inveniri. Ne suspiceris autem me haic ideo elaborasse, quod vos putemus n (ost) ris indigere magisteriis, sed potius ob amore (m) dei tibi soli p (er) scrutinanda pinxisse amicabili fr (ater) nitatis intuitu crede. Vale in Chr (is) o semp (er) memor n (ost) ri ame (n) ”

Translation:

“For you, my dearest son Gozbert, I have written this copy of the plan of the monastery buildings with short remarks, with which you can exercise your ingenuity and in which you can also see my devotion; you can trust me that I will not hesitate to grant your wishes. Do not imagine that I undertook this task assuming that you had to rely on our instructions, but rather believe that I drew this out of love for God and friendly, brotherly zeal for your consideration only. Live well in Christ and always remember us, amen. "

Modern replica

A true-to-original replica of the St. Gallen monastery plan was started in June 2013 in the small town of Messkirch in southern Germany . In the construction of the monastery complex, contemporary building materials and methods are used as far as possible in the sense of experimental archeology , which promises scientific knowledge about Carolingian architecture and construction technology. The construction project initiated by the Aachen journalist Bert M. Geurten receives public start-up aid of around one million euros; the further financing is to be borne by income as a tourist attraction, similar to the Guédelon castle . 20 to 30 construction workers are to be permanently employed on the medieval building site; the construction time is estimated at around 40 years. The project was inspired by Reinhard Kungel's film about Guédelon; Supported by SWR and Baden-Württemberg Film Funding, Kungel has been producing a long-term documentary about the Galli campus in high-resolution 4K since 2011.

Trivia

The Benedictine abbey in Umberto Eco's novel The name of the rose corresponds in principle to the St. Gallen monastery plan.

literature

- Bernhard Bischoff : The development of the St. Gallen monastery plan from a paleographic perspective. In: Bernhard Bischoff: Medieval studies. Selected essays on written and literary history. 3 volumes., Hiersemann, Stuttgart 1966-1981, Volume 1, 1966, pp. 41-49.

- Johannes Duft (Hrsg.): Studies on the St. Gall monastery plan (= communications on patriotic history. Volume 42, ZDB -ID 501261-2 ). Fehr, St. Gallen 1962; Reprints 1963 and 1983.

- Konrad Hecht : The St. Gallen monastery plan. Thorbecke, Sigmaringen 1983, ISBN 3-7995-7018-7 (Unchanged reprint: VMA-Verlag, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-928127-48-9 ).

- Walter Horn , Ernest Born: The Plan of St. Gall. A Study of the Architecture and Economy of, and Life in a Paradigmatic Carolingian Monastery. (= California Studies in the History of Art. Volume 19). 3 volumes. University of California Press, Berkeley CA et al. 1979, ISBN 0-520-03590-9 (Vol. 1), ISBN 0-520-03591-7 (Vol. 2), ISBN 0-520-03592-5 (Vol. 3 ).

- Michael Imhof : Episcopal seats, churches, monasteries and palaces in the vicinity of Charlemagne. In: Michael Imhof, Christoph Winterer : Charlemagne. Life and impact, art and architecture. 2nd updated edition. Imhof, Petersberg 2013, ISBN 978-3-932526-61-9 , pp. 118–236, here pp. 225–229.

- Werner Jacobsen: The monastery plan of St. Gallen and the Carolingian architecture. Development and change of form and meaning in Franconian church construction between 751 and 840. Deutscher Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-87157-139-3 (also: Marburg, University, dissertation, 1981).

- Heinrich Letzing: Once again - the so-called St. Gallen monastery plan. In: Society for the history and bibliography of the brewing industry. Yearbook. 1996, ISSN 0072-422X , pp. 188-190.

- Peter Ochsenbein , Karl Schmuki (ed.): Studies on the St. Gall monastery plan II (= communications on patriotic history. 52). Historical Association of the Canton of St. Gallen, St. Gallen 2002, ISBN 3-906395-31-6 (volume of files from the "St. Galler Klosterplantagung II" from October 27 to 29, 1997, see Werner Jacobsen's research overview: Der St Gallen monastery plan. 300 years of research. Pp. 13–56).

- Hans Reinhardt: The St. Gallen monastery plan (= Historical Association of the Canton of St. Gallen. New Year's Gazette . 92, ISSN 0257-6198 ). Fehr, St. Gallen 1952, digitized version .

- Edward A. Segal: Monastery and Plan of St. Gall. In: Joseph R. Strayer (Ed.): Dictionary of the Middle Ages. Volume 10: Polemics - Scandinavia. Scribner, New York NY 1989, ISBN 0-684-18276-9 , pp. 617-618.

- Barbara Schedl: The plan of St. Gallen. A model of European monastic culture. Böhlau, Vienna et al. 2014, ISBN 978-3-205-79502-5 .

- Ernst Tremp : The St. Gallen monastery plan. Facsimile, accompanying text, inscriptions and translation. Verlag am Klosterhof, St. Gallen 2014, ISBN 978-3-905906-05-9 .

- Ernst Tremp: The St. Gallen monastery plan and the Aachen monastery reform. In: Jakobus Kaffanke (ed.): Benedikt von Nursia and Benedikt von Aniane - Charlemagne and the creation of the "Carolingian monasticism" . (Volume 26: Instructions from the fathers ). Beuron 2016, ISBN 978-3-87071-339-3 , pp. 108-139

- Alfons Zettler: The St. Gallen monastery plan. Considerations about its origin and creation. In: Peter Godman, Roger Collins (Eds.): Charlemagne's Heir. New Perspectives on the Reign of Louis the Pious (814-840). Clarendon, Oxford 1990, ISBN 0-19-821994-6 , pp. 655-687.

Web links

- "St. Gall Monastery Plan Project ”from the University of Virginia

- Reproduced in the Historical Atlas by William Robert Shepherd (1911)

- St. Gallen Abbey Library

- Facsimile in the virtual manuscript library in Switzerland: e-codices

Individual evidence

- ↑ The most valuable document in the pen library . April 11, 2019. Retrieved April 12, 2019.

- ^ Walter Berschin : The St. Gall monastery plan as a literary monument. In: Peter Ochsenbein, Karl Schmuki (ed.): Studies on the St. Gallen Monastery Plan II. 2002, pp. 107–150.

- ↑ Wolfgang Sörrensen: Gardens and plants in the monastery plan. In: Johannes Duft (Ed.): Studies on the St. Gallen monastery plan. St. Gallen 1962 (= communications on patriotic history. Volume 42), pp. 193–277, passim,

- ↑ Christina Becela-Deller: Ruta graveolens L. A medicinal plant in terms of art and cultural history. (Mathematical and natural scientific dissertation Würzburg 1994) Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 1998 (= Würzburg medical-historical research. Volume 65). ISBN 3-8260-1667-X , pp. 105–107 ( The plan of the monastery of St. Gallen ).

- ↑ Christina Becela-Deller: Ruta graveolens L. A medicinal plant in terms of art and cultural history. 1998, pp. 108-110.

- ↑ Werner Jocobsen: The Plan of Saint Gall. 300 years of research. In: Peter Ochsenbein, Karl Schmuki (ed.): Studies on the St. Galler Klosterplan II. 2002, pp. 13–56.

- ↑ a b Florian Huber: The Sankt Gallen monastery plan in the context of ancient and medieval architectural drawings and measurement technology. In: Peter Ochsenbein, Karl Schmuki (ed.): Studies on the St. Gallen Monastery Plan II. 2002, pp. 233–284.

- ↑ Bernhard Bischoff : The emergence of the monastery plan in a palaeographic view. In: Johannes Duft (Ed.): Studies on the St. Gallen monastery plan. 1962, pp. 67-78, here p. 68.

- ↑ Angelus A. Häussling: Liturgy in the Carolingian era and the St. Gallen monastery plan. In: Peter Ochsenbein, Karl Schmuki (ed.): Studies on the St. Gallen Monastery Plan II. 2002, pp. 151–183.

- ^ Walter Horn, Ernest Born: The Plan of St. Gall. 1979.

- ↑ Norbert Stachura: The plan of St. Gallen - an original? In: Architectura. Vol. 8, 1978, ISSN 0044-863X , pp. 184-186; Ders .: The plan of St. Gallen: the west end of the monastery church and its variants. In: Architectura. 10, 1980, pp. 33-37; Ders .: The plan of St. Gallen. Volume 1: Unit of measurement, yardstick and measurements or the dilemma in the dormitory. N. Stachura et al., Saint Just-la-Pendu et al. 2004, ISBN 2-9521744-1-5 ; Ders .: The plan of St. Gallen. Volume 2: The origin of the church dimensions. The author question. Reichenau Abbey and the secret of the dormitory. N. Stachura, Saint Sorlin 2007, ISBN 978-2-9521744-2-8 .

- ^ Barbara Schedl: The plan of St. Gallen. 2014, pp. 93–95.

- ↑ Angelika Franz: Build like 1200 years ago. Meßkirch is carved into the Middle Ages . In: Der Spiegel , March 19, 2012, accessed on November 15, 2015.

- ↑ Klaus Ickert, Ursula Schick: The secret of the rose - decrypted. Wilhelm Heyne, Munich 1986, ISBN 3-453-02461-3 , pp. 29-33.