tattoo

A tattoo (also tatooing ; scientifically also tatooing ; English tattoo [ tə'tu: ]) is a motif that is applied to the skin with ink , pigment or other coloring agents or the incorporation of the motif. For this purpose, the tattoo ink is usually pierced by a tattoo artist (today mostly with the help of a tattoo machine ) through one or more needles (depending on the desired effect) into the second layer of skin and a picture, character, pattern or text is drawn. Today tattoos represent a form of body modification in humans , and in animals it is a label ( animal identification ) for identification.

Origin and Developments

Because of the diverse references scattered all over the world, it can be assumed that the custom of tattooing among the different peoples of the earth developed independently and independently of one another.

Oldest finds

Ötzi

For a long time, the 5300-year-old glacier mummy Ötzi was considered the oldest find of a person with a tattoo. In terms of the number of tattoos, he still holds the record: there are 61, mostly geometric figures, lines and points. They were carved into the body and then colored with some kind of charcoal powder. As they are found in conspicuous places such as the wrists, the Achilles heel , the knees or the chest, researchers such as Albert Zink from the EURAC Institute for Mummies in Bolzano consider it possible that the tattoos also had a medical function. Ötzi could have numbed his back and joint pain with pain therapy, possibly a type of acupuncture .

The mummies from Gebelein

In 2018, a research group led by museum curator Daniel Antoine published a publication in the Journal of Archeological Science that there are even older tattoos: The oldest known tattoos were found on two maximally 5351 year old mummies from Gebelein , a small town in Upper Egypt which are in the British Museum in London. Until this publication, only about a thousand years younger decorations on human skin had been known from Africa.

The female mummy had dark tattoos on her right shoulder and back, an angled line, and four S-shaped marks in a row. Never before had similar old tattoos been found on a woman.

The male mummy carried two horned animals, a large bull and a mighty mane sheep on his right upper arm . Research revealed that the man was killed by a stab from behind when he was around 20 years old.

Since there are no written sources about the two mummies, scientists can only infer the possible meaning of the finds from the context of the finds. It is assumed that the tattoos had a cultural background: The S-lines on the female mummy, which were always arranged in groups, were conspicuous and placed on the shoulder so that they could easily be seen by others, so they should be seen. The second line can be identified as a baton or a clapper, as it was once used in ritual dances. Both line shapes were also found on a clay jar from the so-called predynastic period in Egypt. On a make-up palette from this period, the scientists also found a representation of the mane sheep, as it was tattooed on the male mummy. Bull and sheep also appear on rock carvings, but these are more difficult to classify in time. Daniel Antoine assumes that both animals once stood for masculinity and strength.

Further spread

Particularly elaborate and extensive tattoos are known from the Iron Age Scythians , an equestrian people of the Russian steppe and the Caucasus , and from the Pasyryk culture in the Altai . This seems to refute the frequently held thesis that the custom of tattooing originally came from Southwest Asia, spread from there via Egypt to Polynesia and Australia and was finally carried on to North and South America. In its ritual meaning, it is rooted in various cultures in Micronesia , Polynesia and among indigenous peoples and is also widespread, for example, among the Ainu and Yakuza (Japan) (see e.g. Anci-Piri , tattooing in Palau and Philippine tribal tattoos ).

The Bible reports the following on the subject: “And you should not make an incision in your flesh because of a dead person; and you shall not make etched writing on yourselves . I am the Lord ”(Leviticus 19:28). However, tattoos were common among some early Christian sects. New converts had a large rope (Greek Τ) carved on their foreheads as an image of the cross. Crusaders later followed this custom and stabbed a Latin cross ( se compungunt ) in their skin. In the European Middle Ages , Christian religious tattoos spread. It is said of the scholar and mystic Heinrich Seuse , who lived in the 14th century, that he had the name Jesus tattooed on his chest. A German girl became famous in 1503 because she was tattooed with religious symbols all over her body.

According to Strabon (Geographica), the Karrner , a Celtic tribe of the Austrian Alps, tattooed themselves . According to Herodian (III, 14), the Thracians also got tattoos .

Tattooed warrior from the book by Kvd Steinen : The Marquesans and their art

Tattooed mummy of the "Princess of Ukok", which was found in 1993 in a kurgan near Kosh-Agach (5th – 2nd century BC)

Tāmati Wāka Nene , a Māori with Tā moko , ca.1870

Traditional tattoos on a woman in Suai / East Timor

Function and meaning

Tattoos can have very different functions and meanings. The literature calls u. a. Functions as membership mark and ritual or sacred symbol . Nowadays, tattoos also serve as a means of expressing exclusivity , self-expression , obsession with recognition and demarcation (see also Bourdieu ). Also as a means to reinforce sexual stimuli , jewelry , protest ( punk ) and, last but not least, that of political opinion . Sexual attitudes are also expressed through tattoos. Adolf Loos referred to the tattoo as an ornament in his treatise Ornament und Verbrechen .

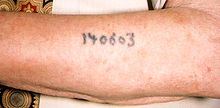

Tattoo for identification

During the Nazi era , inmates of the Auschwitz concentration camp were tattooed with prisoner numbers . Members of the SS had a blood type tattoo on their left inner upper arm.

There are also reports of tattoos on forced prostitutes by pimps.

The tattoo of an identification code is common for many pets and breeding animals, especially when traveling abroad, in order to be able to assign the animal and owner to one another. The brand was used for this on farm animals for a long time . With the increasing use of microchips that are implanted under the skin, there is a viable alternative to tattooing.

Religion and tattoo

Within Judaism , tattoos are sometimes rejected according to Lev 19.28 EU . Tattoos that Jews were forced to do (e.g. number tattoos in concentration camps) are tolerated (as they were done under duress). However, such compulsive tattoos must not be changed or made invisible by further tattoos.

Until 1890, Catholic girls were tattooed in Bosnia to prevent conversion to Islam. Armenian Christians kept the tradition of pilgrim tattooing until World War I ; that was how long this form of marking was offered in Jerusalem. Coptic Christians in Egypt wear a cross on the inside of the right wrist to distance themselves from Islam. Among the Tigray in Ethiopia and Eritrea , the wearing of a tattooed cross from Orthodox Christianity on the forehead is common. In ancient times, Christians were prohibited from wearing tattoos.

“The body is the cathedral of the 21st century. The body is a means of expression and a presentation surface - and it is unique "

Another form of religious tattoo is the yantra tattoo practiced in Southeast Asia - especially in Cambodia , Laos and Thailand .

The Archangel Michael slays the dragon

Permanent make up

A special form is the so-called permanent make-up , in which the contours of z. B. eyes, lips (see also: lip tattoo ) etc. are highlighted, traced or shaded. In this way, surgical scars can also be concealed or an areola can be reconstructed.

Social significance in Japan

Tattoos have a very long tradition in Japan , where they are called Irezumi (Japanese 入 (れ) 墨 , literally: "to bring in ink") or horimono ( 彫 (り) 物 , literally: "sculpture, carving"). The earliest mention can be found in the Chinese historical work Weizhi Worenchuan , in which the Japan of the 3rd century is described. In addition, tattoos ( Anci-Piri ) can also be found among the Ainu , the northern Japanese indigenous population.

At the beginning of the Edo period (1603 to 1868), tattoos were very popular with prostitutes and workers, among others. From 1720 the tattoo was used as a kind of branding for criminals, which is why "decent" Japanese no longer let themselves be tattooed. Anyone who was marked as a criminal could no longer integrate into society, which led to the formation of a separate class: the yakuza . Under the Meiji government , this practice was abolished in 1870, tattoos were completely banned, which was not repealed until 1948.

Although stylistically very uniform, there is a great variety of motifs, which are often taken from mythology, such as dragons or demons , which often come from legends and tell a whole story. Or there are symbols such as cherry blossoms (beauty and joy, but also transience) and Kois (success, strength and luck). A style of bloody and gruesome chopped off heads developed when scary stories became extremely popular in Japan in the late 19th century. A Japanese custom is to be tattooed by a single artist throughout your life; often large-scale paintings all over the body over the years, which are finally signed by the artist.

Tattoos are still stigmatized in Japan and are often interpreted as being entangled in a criminal environment. They are an important part of the yakuza culture (especially the so-called bodysuits that occupy the entire torso ). In some public baths, people with large tattoos are refused entry. But just like in the West, tattoos are becoming more and more popular, especially among young Japanese, and are therefore trusted by a broader social class. Nowadays there are many world-famous tattoo artists in Japan (for example Horiyoshi III ) who pass their skills on to their students. On the other hand, the prevalence of tattoos among gang members is decreasing because they don't want to attract attention. Thus, in Japan, the connection between crime and tattooing is dissolving.

Recently, Japanese-style tattoos are enjoying increasing popularity in Western cultures as well.

Yan Qing from the novel Die Räuber vom Liang-Schan-Moor , color wood print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (around 1827)

Tattooed Japanese, hand-colored photograph by Felice Beato (around 1870)

Tattooed Yakuza at the Sanja Matsuri -Festival in Asakusa , Tokyo (2007)

Social significance in the western world

Tattoos originally had the stigma of the sailor or convict in the West and are used by US and Latin American youth gangs as a sign of belonging, but have been enjoying greater popularity since the 1990s at the latest. What began primarily as an expression of a youth culture that also includes piercing and branding can now be found in broad strata of society. Numerous celebrities who showed themselves publicly with tattoos contributed to an increasing acceptance. However, tattoos are still used as code and language within criminal gangs. For example, among supporters of the Russian group Thieves, the tattooed motives show crimes committed, years of prison service or the hierarchy within the group. The so-called prison tear under the eye can be stung by prisoners who have spent more than ten years in prison.

Despite the social stigmatization of tattooed people, tattoos used to be widespread in the highest social circles, even though they were not worn in public. The most prominent bearers are the British King George V (1865–1936), the Spanish King Alfonso XIII. (1886–1941) or the Danish King Frederik IX. (1899–1972). Even the Empress Elisabeth of Austria-Hungary ( Sissi , 1837–1898) had an anchor tattooed on her shoulder in 1888 at the age of 51.

Children use temporary tattoo that can be easily removed again, but the term tattoo or tattoo firmieren. Analogous to this, there are also so-called henna tattoos , which are not pierced into the skin, but rather painted on. Here only the horny layer of the epidermis is colored. Since these keratinized cells are continuously flaking off, the supposed tattoo disappears after a few weeks.

This development shows the approach of tattooing to the mainstream , as it enables a tattoo as a fashion accessory. Even the organic tattoo supposedly disappears by itself after a few years because the sting is not that deep. In reality, however, this happens very rarely, if at all, as it is virtually impossible to work so precisely that the prick is neither too shallow (the tattoo disappears during the healing process) nor too deep (the tattoo remains). At least parts or a shadow of the tattoo are mostly retained. Therefore, serious tattoo artists warn against it. The Karlsruhe Higher Regional Court sentenced a tattoo artist to pay damages and compensation for pain and suffering because she had assured the customer that the organic tattoo would disappear after three to seven years - which did not happen.

The proportion of tattooed people in the German population is increasing. The proportion of tattooed men between the ages of 25 and 34 increased from 22.4% (2003) to 26% (2009), and that of tattooed women between 25 and 34 years even almost doubled from 13.7% (2003) to 25.5% (2009). The most popular spots were the arms and back. In Germany, almost one in five adults now has a tattoo (as of April 2018). In particular, the proportion of women and older people tattooed increased. In 2017, around half of all women between the ages of 25 and 34 were tattooed. This means that this group of women rose by more than 19 percent between 2009 and 2017 alone. There was a 15 percent increase in the number of tattooed women in women aged 35 to 44.

In Austria, the IMAS institute surveyed Austrians over the age of 16 in April / May 2016: Almost a quarter of them are tattooed, and 40 percent of those under 35.

According to a survey by the Gesellschaft für Konsumforschung (GfK) in 2014, 5 to 15 percent of all tattoo wearers regret having a tattoo.

Occupational restrictions and the "T-shirt limit"

Tattoos and piercings are private matters that are fundamentally subject to personal rights. According to Steffen Westermann, spokesman for the career strategy office Hesse / Schrader, the boss should not prohibit body jewelry. Nevertheless, there are many unwritten laws in the world of work. Often times, the first impression decides whether an employee “fits into the team”, even in creative professions. A rejection is seldom justified with the conspicuous body jewelry, but mostly with doubts about competence. In industries with regular customer traffic, tattoos are only allowed within the so-called "T-shirt limit". This is the area that can be covered by a standard T-shirt. The Baden-Württemberg Ministry of the Interior abolished the T-shirt limit in 2017. This means that police officers can also wear tattoos on their forearms, but they must be subtle in terms of size and motif. Motives glorifying violence, discriminating or politically sensitive are prohibited.

The central service regulation of the Bundeswehr A-2630/1 has been regulating the external appearance of soldiers in the Bundeswehr since January 2014 . According to this, soldiers should "cover up visible tattoos in a suitable and discreet manner" when wearing a uniform.

In May 2020, the Federal Administrative Court decided by the highest court that an externally recognizable tattoo is not compatible with the neutrality and representational function of uniform wearers according to the Bavarian Civil Service Act. A police officer wanted to have the word Aloha tattooed on his forearm in 15 by 6 centimeters. The regulations of different federal states are different. Visible tattoos of smaller size are allowed in Berlin. In Rhineland-Palatinate, visible tattoos must be covered.

Motifs, styles and new trends

At the beginning of the 20th century, tattoos were almost exclusively seen on sailors, soldiers or prisoners, but a general trend towards tattoos has developed since the late 1980s. Certain music scenes also made tattoos a part of their subculture.

In the 1990s, so-called tribal tattoos experienced their heyday. Tribals (sometimes also called Iban) found their way under the skin in various forms. Especially with women who wore them, they could be found placed on the rump under the joking designation butt antlers .

At the end of the 1990s there was a trend towards so-called old-school motifs in the tattoo scene. These are motifs that often have their origin in ancient sailor tattoos. Examples of motifs in this genre are stars, swallows, anchors or hearts.

Further trends are so-called geek or nerd tattoos. The motifs usually come from the academic sector or the computer sector and reflect the growing popularity of geek style and nerdcore . Furthermore, in so-called biomechanical tattoos , motifs of skin openings, behind which muscles, organs or machine parts are visible, are used.

During the "cover-up", unloved tattoos are covered by other, larger motifs.

Science and art

Germany

On July 2, 1970, the artist Valie Export had a garter tattoo by Horst Straßenbach at a public event in Frankfurt . "The own body is painfully and permanently marked with a garter belt - a fetish of male sexual fantasies - in order to expose the functionalization and social role of women as a sexual object and to reflect their social determination by the man." The philosopher Simone de Beauvoir put it: “You are not born a woman, you are made into it.” In 1971, at the 4th experimenta in Frankfurt , Straßenbach met Timm Ulrichs , who had the signature timm ulrichs 1940 -… tattooed as the “first living work of art” . On his right eyelid, he got a tattoo of the words “The End” from Linienbach (Frankfurt / Main) in 1981 - the credits for the ultimate film. True to his motto "Total art is life itself", Ulrichs had his own signature tattooed publicly on his upper arm in 1971. Not the only tattoo: “Copyright by Timm Ulrichs” has recently been written on his foot.

The tattoo artists Manfred Kohrs (Hanover) and Horst Linienbach (Frankfurt / Main) worked in the late 1970s to introduce German tattoo artists to the artistic scene; also to take away from the profession the habitus of the “half silk”, which was still extremely present in those years. In the years 1977 to 1981 Manfred Kohrs - as a member of the art association - created several individual projects on the subject of tattoos. In 2015, as part of the exhibition Skin Stories in the Kunst Galerie Fürth , in addition to works by u. a. with Natascha Stellmach , Timm Ulrichs , Wim Delvoye , Simone Pfaff and Volker Merschky , a tattoo machine by Manfred Kohrs was also exhibited.

The Berlin artist Ingeborg Leuthold has been working with motifs of tattooed people since 1985. Inspired by the Love Parade and Christopher Street Day, she deepened her work on the subject, which culminated in the 2010 exhibition Tattoo total or the longing for paradise lost .

With his research on tattoos, the German art historian and curator Ole Wittmann “for the first time brought tattoos into the focus of an art-historical perspective.” His dissertation, Tattoos in Art , was published in 2017. With the special exhibition Tattoo Legends. Christian Warlich on St. Pauli , the Museum für Hamburgische Geschichte showed for the first time an exhibition on German tattoo history for a broad audience from November 27, 2019 to May 25, 2020.

Switzerland

The pop-art artist Marco De Lucca and tattoo artist Dietmar "Dischy" Gehrer from Rheineck worked together in 2012.

International

In September 1995 Ed Hardy showed the exhibition "Pierced Hearts and True Love" in the New York art gallery The Drawing Center . In this exhibition, which was a "decisive step towards improving the image of tattooing", Hardy gave a historical overview of the past 100 years.

The American artist Shelley Jackson created an art project in 2003 called "The skin project". She wrote a short story of 2095 words, which were not printed, rather volunteers had one word of the story tattooed on each other.

Exhibitions (selection)

- 2017/2018: GRASSI invites # 4: Tattoo and Piercing , GRASSI Museum für Völkerkunde Leipzig.

- 2015: tattoo , Museum of Arts and Crafts Hamburg .

- 2015: Skin Stories , Art Gallery Fürth .

- 2013/2014: Tattoo , Gewerbemuseum Winterthur .

- 2013: Razor Sharp - Tattoos in Art, Museum Villa Rot

- since 2002: GAT - Greetings from Tattoos , annual exhibition with changing topics

Forensic medicine and criminal investigation

Criminal investigators and coroners use tattoos to identify bodies and locate suspects.

Use in medicine

Horst Streckenbach was the first tattoo artist who proved in 1976 worked in the medical field and after a breast cancer operation a Mamillenrekonstruktion undertook. The process was called "Straßenbach - Technik" in the med. Literature taken over. Starting in 1983, tattoo artist Manfred Kohrs carried out tattoos to reconstruct the areola after performing breast reconstructions. In the period that followed, Kohrs supplied some German clinics with the appropriate equipment and trained doctors. In ophthalmology, there is a seldom used method of reconstructive surgery known as keratography or corneal tattooing . In this process, near-natural color pigments are applied under the cornea of the human eye . It is used for plastic improvement in severe cosmetic distortions caused by illnesses or injuries to the anterior sections of the eye ( iris , pupil , etc.). Although keratography carries a certain risk and can be associated with complications, it can nevertheless be suitable for patients in whom restoration of vision is no longer expected. Such procedures have been known for almost 2000 years, but have long been forgotten and have been experiencing a renaissance in the last few years , albeit only for a limited number of those affected. The procedure of tattooing is listed under the International Classification of Treatment Methods in Medicine as a surgical procedure under the Operation and Procedure Code 5-890 (tattooing and introduction of foreign material into the skin and subcutaneous tissue) .

etymology

Both the German word “tatowieren” and the English “tattoo” ( ˌtæ'tuː ) have their origins in the Polynesian languages . The Samoan word tatau (as a skin ornament or sign) can be translated as "correct" and means something like "correct [to wrap the skin or pattern]" or "straight, artfully". After James Cook's arrival in England in 1774, the term spread throughout Europe. In the English military language there was an identical word (from Dutch taptoe ) since the middle of the 17th century, it still describes the tattoo today . In England the term tattow was used alongside the initially common tattaow , which was then replaced by tattoo (from Marquesan tatu ), which is used exclusively today. The fact that in England it was initially mostly soldiers who had themselves tattooed could have promoted the replacement of the word.

In the German-speaking world, the terms tattooing and tattooing coexisted for a long time, until the term tattooing finally caught on at the beginning of the 20th century. In ethnology , however, tattoos and tattoos are still mostly used.

technology

Jewelry tattoo

The process of tattooing basically consists of puncturing the skin, with a dye being introduced into the skin at the same time as the piercing. Make sure that the stitch is neither too superficial nor too deep. In the first case, the stored colorant would only be introduced into the cell layers of the epidermis . The consequence of this would be that, with the continuous renewal of this skin layer, the colorant particles would grow away and be repelled to the outside at the same time as the epidermal cell layers. In the second case, if the prick is made too deep into the skin, the bleeding that occurs causes the dye to be washed out. Those colorants that are stored in the middle layer of the skin ( dermis ) in the cell type of fibroblasts are durable .

The speed depends on the tattoo machine, the technology and the desired effect, e.g. B. lines or shades, but is between approx. 800 to 7,500 movements per minute. Thanks to a capillary effect, the ink stays between the needles and, thanks to the speed of movement, is brought into the skin just as easily as when drawing with a pen on paper. The skin is held under tension with one hand, the other hand brings in the image. First, the contour is created - mostly with black color - and - if necessary - the shadow effect is introduced; then the corresponding areas are filled in with color. The choice of needle size and strength used depends on the motif and the technique used.

There are other ways of creating permanent skin drawings, for example cutting the skin and rubbing the wound with ink , ash or other coloring substances (so-called ink rubbing ), or tattooing with a needle and thread , in which a needle wrapped with thread is inserted Ink, Indian ink or other coloring matter is dipped and then stabbed into the skin; this process is also known colloquially as "peiken" or "peikern". In the 19th century, Austrian soldiers and common soldiers tattooed themselves with incisions with "name ciphers" or signs of the cross, and gunpowder was used as a dye .

The Polynesian peoples used a tattoo comb, which was made from different parts of plants or bones and attached to a long stick. The tips of the comb were driven into the skin by rhythmically striking the handle, where they brought in an ink made of water and ash or burnt nuts. These ridges came in different widths, but they always left lines, never points. The traditional Japanese tattoos, known as Irezumi , are still often made by hand today, although western tattoo machines have long enjoyed great popularity in Japan , and this technique is called Tebori .

The Eskimos, on the other hand, pulled threads or sinews soaked with color under the skin in order to obtain a permanent mark.

Grunge tattoo

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| L81.8 | tattoo |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

In addition to decorative tattoos, the (undesired) penetration of colored particles into the connective tissue of the skin is also referred to as tattoos in medicine - as "dirty tattoos".

The causes are mostly accidents with fireworks, powder smoke injuries and road accidents. But even if you fall “on ashes ” with a graze, coloring particles can get under the skin. Iron-containing metal fragments in the skin cause a brown discoloration ( siderosis ). Dirty tattoos with coal dust occur on miners .

While dirt particles can usually be removed by brushing them out without cosmetic consequences in the first 72 hours, a punch excision must usually be performed later .

Legal bases

Germany

The tattooing of minors is possible to a certain extent, a declaration of consent from the parents is sufficient. Since many tattooists are not satisfied with a written declaration of consent, they require at least one parent to be present during the entire session.

According to § 294a SGB V , doctors and hospitals are obliged to report complications with tattoos to the health insurance companies. In addition, there is no entitlement to continued remuneration in the event of incapacity for work , as the employer only has to bear the normal risk of illness for the employee.

Since 2018, according to police regulations, the wearing of visible tattoos has been permitted for police employees in Berlin.

Austria

According to Section 2 Paragraph 1 Clause 4 of the Ordinance on the “Rules for Piercing and Tattooing”, children aged 16 and over can be tattooed. However, both the minor and the person entrusted with the care and upbringing of the minor must give their written consent.

Switzerland

The tattooing of minors is allowed if the young person is able to judge . This is usually available from the 14th birthday and is anchored in Article 16 of the Swiss Civil Code (ZGB) .

Health hazards

infection risk

Strict hygiene regulations must be observed when tattooing. These are not always checked, so some caution is advisable. It can lead to HIV, hepatitis and various other infections. In the Netherlands, Switzerland and Austria tattoo studios are subject to strict requirements and controls, which was very beneficial for general health safety in this area. Interventions, sterilization processes, cleaning and disinfection measures are now being documented there in writing. In Austria, the annual provision of a safety certificate by an accredited institute has been required by law since 2003 (see Federal Law Gazette 141/2003).

There is also a risk of infection from fresh, not yet fully healed tattoos: there is a risk of becoming infected with the Vibrio vulnificus bacterium while bathing . The infection can be fatal in weakened people.

Harmful dyes

Research has shown that some of the dye in tattoo ink is carried away from the dermis to other areas of the body. Since, in contrast to cosmetics, there were hardly any legal regulations for the colors used, they often contained heavy metal compounds as pigment, for example . In addition, azo inks in particular are considered problematic, as they break down under the action of UV light into harmful substances such as azele hydrochloride or various hydrocarbons (both cell toxins).

The Stiftung Warentest examined ten tattoo inks in 2014. In six colors, the testers identified ingredients that can make you sick or dangerous for allergy sufferers . Two colors contained poisonous polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs).

When tattoos are removed by laser treatment, the color pigments used, in particular the frequently used red color pigments Pigment Red 22 and Pigment Red 9, can lead to carcinogenic substances such as 2-methyl-5-nitroaniline.

Pigments from tattoo inks penetrate not only into the skin, but also into the body. In some cases, lymph nodes that are close to tattoos are also colored. In 2003 the Council of Europe published the resolution ResAP (2003) 2 on tattoos and permanent make-up , in particular to punish cancer-endangering substances; it was updated in 2008. Germany issued the Tattoo Inks Ordinance in November 2008 . It came into force on May 1, 2009.

Some hospitals refuse epidural anesthesia to patients with tattoos above the tailbone ("ass antlers") during childbirth. The reason is a high risk of infection from colored pigments that enter the body with the needle that penetrates between the lumbar vertebrae. The damage caused by color pigments in the body has not yet been adequately researched, the risk of serious injuries and / or nerve damage is considered to be too high compared to the benefits.

Burns during magnetic resonance imaging

The occurrence of a burn during the tomographic examination is extremely unlikely and the degree of severity of such a burn to be expected is low. However, the occurrence of ring artifacts is more likely than damage to the patient .

Eyeball tattoo

The eyeball tattoo is considered a health risk .

distance

Carelessly engraved tattoos, technical failures, changing trends in fashion, or the changed acceptance of once modern motifs, such as B. the so-called ass antlers , make the wearer want to remove the unwanted tattoos. In many cases, the undesired motif is covered with a new tattoo or incorporated into another motif (“cover-up”). Various methods have been tried to remove tattoos, such as: B. scraping or cutting out the skin, diathermy , water jet cutting , the magnetic removal of magnetic tattoo pigments, the chemical removal with acids, or the removal with laser technology.

Acid solution

In the 1920s and 30s, the Hamburg tattoo artist Christian Warlich experimented with methods of removing tattoos. He developed acid-based tinctures from distilled water , potash, table salt , sulfuric acid and ether . This was applied to the skin and peeled off the tattooed skin layer, then the skin with the colored layer could be peeled off. However, this method, described as painless, left scars on the skin. Warlich was so successful that the Eppendorf University Medical Center (UKE) referred patients to him. However, his unexpected death prevented this method from spreading further. In the 1960s / 1970s, the physician Claus Udo Fritzemeier researched standard tattoo removal solutions and was able to understand Warlich's recipes.

Current preparations are solutions that usually contain 40% L - (+) - lactic acid . Similar to tattoo inks, a needle is inserted under the epidermis and the liquid removal agent is injected under the skin. According to the provider, the body should naturally repel the color pigments. Although comes L - (+) - lactic acid in natural form in the human body; Studies have nevertheless shown that the use of such tattoo removers is associated with health risks due to the irritating effects of lactic acid in high concentrations (40%). Cases of severe scarring skin inflammation have been reported. According to the state of the art, irritative effects on the skin and mucous membranes occur at a concentration of 20% lactic acid in formulations . In the eye, this is possible even with a lower concentration of lactic acid. Due to the relative novelty of the forms of treatment, neither clinical evaluations nor results of clinical studies on long-term effects are available. Above all, it is unclear which chemical compounds are formed during treatment with lasers or lactic acid and which late health risks they pose. It is assumed that some of the split color pigments accumulate in the liver, spleen and lymph nodes.

laser

When removing tattoos, lasers are in the foreground because of their relatively good results, their good tolerance and their high level of development. On the one hand, there is the Q-switched Nd: YAG laser , the frequency-doubled Nd: YAG ( KTP ), the Q-switched ruby laser and, above all, the new picosecond laser . The wavelength (color) of the laser, which must be matched to the color (wavelength spectrum ) of the color pigments, is decisive for the success of the treatment . Black and dark blue tattoos can be removed particularly well with the ruby laser and Nd: YAG laser, whereas the frequency-doubled Nd: YAG laser (KTP) is used for red to yellowish tattoo inks. The ruby laser works more effectively with green colors. Picosecond lasers work - depending on the equipment - very well with all colors of a tattoo. In addition, the latter have the advantage that they work with light pulses that are around 100 times shorter than the other lasers mentioned. As a result, the paint is barely heated and torn into smaller particles, which the body can break down more quickly and with fewer side effects.

When a tattoo is created, the color pigments are partially encapsulated by the body's own cells - the macrophages - during the healing process (up to about two weeks after the sting) . Part of the color goes directly into the body, part of the color remains in the dermis as a visible tattoo.

These macrophages can be "broken open" with the use of various lasers. This is done by irradiating the enclosed color pigments, which quickly expand and contract again due to the absorption of light, causing them to break down into smaller particles that the body can transport away. However, this is sometimes followed by re-encapsulation, which means that the laser treatment has to be repeated (between two and 20 treatments, depending on the color and laser used).

During the treatment, a discoloration of the tattoo can be seen, which is due to the different degradation rates of the pigments of one color. Since it is very difficult to assess the composition of the color and the reaction to the treatment in advance, it is advisable to try out the treatment on a small area beforehand. Some color pigments can release substances classified as carcinogenic when they break down.

A change in the law from 2018 stipulates that from 2021 onwards, only doctors in Germany may perform laser treatments to remove tattoos.

Contribution to the cost of complications

Statutory insured persons who have undergone a medically not indicated measure, such as cosmetic surgery , a tattoo or a piercing , also have to contribute appropriately to the costs of a complication resulting therefrom, including the daily sickness allowance. Doctors and hospitals are obliged to notify them of secondary illnesses of medically unnecessary treatments .

Examples

Reports and documentaries (selection)

- Tattoo totally! Arte documentation, 2013

- Modify

- Flammend 'Herz ( documentary )

- Under the Skin (Documentary)

- Series on DMAX : Miami Ink , LA Ink and Tattoo - A family stabs

- 1975: Nordschau magazine : “Happening at the Kunstverein Hannover. ' Sammy ' from Frankfurt on his art and tattooing ”.

- Oliver Steinkrüger: Christian Warlich estate, King of Tattoo Artists. Part 8 of the documentary series Tattooing Über Alles

- Christian Warlich - Documentary - NDR - Typical! - March 23, 2017

See also

Trade journals (selection)

Literature (selection)

- Kai Bammann, Heino Stöver (Ed.): Tattoos in the penal system. Adhesion experiences that get under the skin. 2006, ISBN 3-8142-2025-0 . (Full text)

- Marcel Feige : Tattoo and Piercing Lexicon - Cult and Culture of Body Art. Schwarzkopf & Schwarzkopf, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-89602-541-4 .

- Frank-Peter Finke: Tattoos in Modern Societies. Rasch, Osnabrück 1996, ISBN 3-930595-45-1 .

- Erich Kasten: Body Modification. 1st edition. Reinhardt Verlag, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-497-01847-3 .

- Lars Krutak : Kalinga Tattoo: Ancient and Modern Expressions of the Tribal. Edition Reuss, Glattbach 2010, ISBN 978-3-934020-86-3 .

- Albert L. Morse: The Tattoists. 1st edition. 1977, ISBN 0-918320-01-1 .

- Stephan Oettermann : Signs on the skin. The history of the tattoo in Europe. (= Paperback syndicate EVA. 61). Syndikat, Frankfurt am Main 1979. (3rd edition. Europäische Verlags-Anstalt, Hamburg 1994, ISBN 3-434-46221-X ( EVA-Taschenbuch. 221). Also translation into Swedish 1984, ISBN 91-7139-280-7 .)

- Oliver Ruts, Andrea Schuler (Ed.): BilderbuchMenschen. Tattooed Passions 1878–1952 . Photos by Herbert Hoffmann. Memoria Pulp, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-929670-33-X .

- Karl von den Steinen: The Marquesans and their art . Volume 1, tattooing. Reimer Verlag, Berlin 1925. (Newly published as a facsimile reprint by Fines Mundi Verlag, Saarbrücken 2006.)

- Ulrike Landfester: Tattoos and European writing culture. Matthes & Seitz, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-88221-561-8 .

Medical literature

- Health hazards from tattoos and permanent make-up . (PDF; 133 kB) Federal Institute for Risk Assessment , 2007.

- Risk of infection from tattoos . (PDF) Federal Institute for Risk Assessment, 2014.

- Tattoos: Color pigments also migrate in the body as nanoparticles . In: Synchrotron-based ν-XRF mapping and μ-FTIR microscopy enable to look into the fate and effects of tattoo pigments in human skin. In: Scientific Reports. 7, 2017, doi: 10.1038 / s41598-017-11721-z , Federal Institute for Risk Assessment

- S1 guideline of the Association of Scientific Medical Societies in Germany : Tattooing: Requirements of hygiene . 2013.

- Jørgen Serup, Nicolas Kluger, Wolfgang Bäumler: Tattooed Skin and Health. (= Current Problems in Dermatology. Volume 48). Karger 2015, ISBN 978-3-318-02776-1 .

- M. Dirks: Making innovative tattoo ink products with improved safety: possible and impossible ingredients in practical usage. In: Tattooed Skin and Health. (= Current Problems in Dermatology , Vol. 48). 2015, pp. 118–127, doi: 10.1159 / 000369236 . PMID 25833633 (Review).

- Paola Piccinini, Laura Contor, Ivana Bianchi, Chiara Senaldi, Sazan Pakalin: Safety of tattoos and permanent make-up - Compilation of information on legislative framework and analytical methods. Joint Research Center of the European Commission , 2015, ISBN 978-92-79-58783-2 , doi: 10.2788 / 011817 .

- Wolfgang Bäumler: The possible health consequences of tattoos. In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt Int. , Volume 113, 2016, pp. 663-674. doi: 10.3238 / arztebl.2016.0663 .

- R. Dieckmann, M. Goebeler, A. Luch, S. Al Dah S: The risk of bacterial infection after tattooing - a systematic review of the literature. In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt Int. , Volume 113, 2016, pp. 665-671. doi: 10.3238 / arztebl.2016.0665 .

- S. Jungmann, P. Laux, T. Bauer, H. Jungnickel, N. Schönfeld, A. Luch: From the tattoo studio to the emergency room. In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt Int. , Volume 113, 2016, pp. 672-675. doi: 10.3238 / arztebl.2016.0672 .

Literature science and art

- Adolf Spamer : The tattoo in the German port cities. An attempt to capture their forms and their image quality. Trickster 1993, ISBN 3-923804-69-5 .

- Ole Wittmann : Tattoos in Art: Materiality - Motifs - Reception. Dietrich Reimer Verlag, 2017, ISBN 978-3-496-01569-7 .

- Paul-Henri Campbell : Tattoo & Religion. The colorful cathedrals of the self (interviews and essays). Verlag das Wunderhorn, Heidelberg 2019, ISBN 978-3-88423-606-2 .

Web links

- Link catalog on the topic of tattoos at curlie.org (formerly DMOZ )

- Andreas Weigel : Tattoos set to music Selected songs about tattoos (ORF, Ö1, Spielräume . November 22, 2009, 5: 30–5: 55 pm).

- Hollywood stars as tattoo trendsetters . Mirror online

- Traditional symbolism & meaning

Individual evidence

- ↑ tattoo . Duden.

- ↑ Matthias Gauly, Jane Vaughan, Christopher Cebra: Neuweltkameliden : keeping, breeding, diseases. Georg Thieme Verlag, 2010, ISBN 978-3-8304-1156-7 , p. 32.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Hubert Filser: The oldest tattoos in the world. Mummies with 5350 old skin ornaments. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung , March 6, 2018, p. 14.

- ↑ Natural mummies from Predynastic Egypt reveal the world's earliest figural tattoos. In: sciencedirect.com. January 31, 2018, accessed March 7, 2018 .

- ^ Susanna Elm : Pierced by Bronze Needles: Anti-Montanist charges of ritual stigmatization in their Fourth-Century context. In: Journal of Early Christian Studies. Volume 4, 1996, pp. 409-439.

- ↑ Stefan Winkle : Cultural history of epidemics. Artemis & Winkler, Düsseldorf / Zurich 1997; Licensed edition for Komet, Frechen, ISBN 3-933366-54-2 , pp. 15 and 1086.

- ↑ Maarten Hesselt van Dinter: Tatau: Traditional tattooing worldwide. 1st edition. Arun-Verlag, 2009, ISBN 978-3-86663-026-0 .

- ↑ neumarkt-dresden.de. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on September 21, 2008 ; Retrieved September 3, 2008 .

- ^ Andreas Jordan: The prisoner number in Auschwitz. In: The identification of the concentration camp prisoners. Gel Center, accessed April 19, 2018 .

- ↑ Beaten, shaved and tattooed for attempting to escape . Welt Online , March 26, 2012; accessed on April 4, 2018.

- ^ Johannes Wachten (deputy director of the Jewish Museum in Frankfurt am Main): Body images in Judaism. Journal of Ethnology, 2006.

- ↑ Bar Rav Nathan: "Ask the Rabbi": Tattoos and burials. Statement of a rabbi at Hagalil

- ↑ By Pope Hadrian I in the Council of Calcuth and in ( Lev 19.28 EU ), ( Lev 21.5 EU )

- ↑ Anken Bohnhorst-Vollmer: Spiritual Tattoos - That gets under the skin. In: kirchenzeitung.de. June 1, 2016, accessed July 10, 2018 .

- ↑ Chean Rithy Men: The Changing Religious Beliefs and Ritual Practices among Cambodians in Diaspora. In: Journal of Refugee Studies. Vol. 15, No. 2 2002, pp. 222-233.

- ↑ Jana Igunma: Human body, spirit and disease: the science of healing in 19th century Buddhist manuscripts from Thailand. In: The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Universities. Vol. 1 2008, pp. 120-132.

- ↑ Criminologist decrypts tattoo codes ( memento from June 10, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Tagesschau (ARD) , June 7, 2009.

- ↑ Martin Kotynek, Stephan Lebert, Daniel Müller: Penal system: Die Schlechterungsanstalt . In: The time . August 16, 2012, ISSN 0044-2070 ( zeit.de [accessed October 6, 2017]).

- ↑ Gewerbemuseum Winterthur and Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg (ed.): TATTOO 02/13. until September 6th, 2015: an exhibition by the Winterthur Gerwerbemuseum . 2015, p. 10 ( PDF [accessed on May 11, 2020] booklet accompanying the special exhibition).

- ↑ Hellmuth Vensky: Sisi, the bullied empress. In: Zeit Online. December 26, 2012, accessed May 11, 2020 .

- ↑ Sabrina Kamm: Tattooist is liable for permanent "organic tattoos". ( Memento from August 4, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ) In: Justiz-bw.de , March 27, 2014.

- ^ Dissemination of tattoos, piercing and body hair removal in Germany. ( Memento from April 24, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b Nadine Zeller: The proof is on the skin. In: sueddeutsche.de . April 2, 2018, accessed April 3, 2018 .

- ↑ Study: Every fifth German is tattooed Leipziger Volkszeitung from September 22, 2017.

- ↑ Österreichischer Rundfunk : Almost a quarter of Austrians have tattoos. on June 24, 2016, accessed June 24, 2016.

- ↑ Tribal, Arschgeweih: This is what tattoos say about their wearers from the Berliner Zeitung from February 10, 2015

- ↑ Tonio Postel: Tattoos - Drawn for life. faz.net, April 22, 2009.

- ↑ Naive Lexicon (episode 2465) - What is the “T-Shirt Limit”? BZ, September 27, 2010. Retrieved May 18, 2013.

- ↑ Tonio Postel: Tattoos - Drawn for life. faz.net, April 22, 2009 ( p. 2/2. ), accessed on May 17, 2015.

- ↑ Stuttgart Ministry of the Interior: Land loosens regulations for police officers with tattoos. In: Stuttgarter Nachrichten. Retrieved July 11, 2019 .

- ↑ Bundeswehr Style Guide. In: FAZ . Retrieved November 28, 2014 .

- ↑ Wednesday, January 22nd, 2014 The Bundeswehr's new fashion etiquette. Hide your tattoo, comrade! In: n-tv.de. January 22, 2014, accessed November 28, 2014 .

- ↑ No "Aloha": Police officer fails with tattoo lawsuit welt.de on May 15, 2020, accessed on May 18, 2020

- ↑ Origin: Tribals were tribal badges ( Memento from July 15, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Tattoos are also subject to fashion. Mitteldeutsche Zeitung.

- ^ Revenge of the Tattooed Nerds. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on November 14, 2011 ; Retrieved June 14, 2010 .

- ↑ "Worlds of Tattooed Biomechanics". In: Tattoo Spirit . May 27, 2014, accessed April 4, 2015 .

- ↑ Thomas Trenkler: VALIE EXPORT: “I wanted out” . On April 14, 2015 on thomastrenkler.at (excerpt from I fell into a world - conversations about art and life . Brandstätter Verlag, Vienna 2013, ISBN 978-3-85033-607-9 )

- ↑ Samy tattooed seven skins. In: HAZ . January 27, 1975.

- ^ Museum for Art and Commerce Hamburg, booklet for the exhibition Tattoo vo. February 13 to September 6, 2015, No. 31 (PDF) Retrieved June 6, 2015 .

- ↑ kunsttempel.net THE END, eyelid tattoo, 1970, May 16, 1981.

- ↑ Christina Sticht, Timm Ulrichs: Pioneer of Conceptual Art. nw-news.de, March 31, 2010.

- ↑ a b mkg-hamburg.de : tattoo

- ↑ a b Rainer Hertwig on August 17, 2015: Analog messages under the skin

- ↑ Ingeborg Leuthold, Tattoo total or the longing for the lost paradise. Catalog. Ladengalerie Müller GmbH, 2010, ISBN 978-3-926460-90-5 .

- ↑ Stefanie Handke: Ole Wittmann: Tattoos in art. Materiality - Motives - Reception, Reimer 2017. In: portalkunstgeschichte.de. December 12, 2017. Retrieved July 29, 2019 .

- ^ Foundation Historical Museums Hamburg: Tattoo Legends. Christian Warlich on St. Pauli. In: Ruhr University Bochum word mark. April 11, 2018. Retrieved July 29, 2019 .

- ↑ olewittmann.de lectures, accessed on July 29, 2019

- ↑ Pop art meets tattoo art in Tagblatt from September 13, 2012

- ↑ Marcel Feige : The tattoo and piercing lexicon. ISBN 3-89602-209-1 , p. 147.

- ^ Mary Flanagan, Austin Booth: Re: Skin MIT Press 2009, ISBN 978-0-262-51249-7 , p. 13.

- ^ Museum of Ethnology in Leipzig: GRASSI invites # 4: Tattoo & Piercing. Retrieved March 30, 2019 .

- ↑ Gewerbemuseum.ch

- ↑ razor sharp. Retrieved February 4, 2019 .

- ↑ Obstetrics and women's health dogs. Volume 36, Issue 1, 1976, p. 13. (books.google.de)

- ↑ Stadtkind Hannovermagazin: Interview: Manfred Kohrs. Edition July 2016, p. 47.

- ↑ Sabrina Ungemach in Tattoo Kulture Magazine . No. 22, 2017, p. 48.

- ↑ Susanne Pitz, Robert Jahn, Lars Frisch, Armin Duis, Norbert Pfeiffer: Cornea tattoo - today's significance of a historical treatment method. In: The ophthalmologist. Volume 97, Number 2, 2000, pp. 147-151.

- ↑ OPS-2018 5-890 Tattooing and introduction of foreign material into the skin and subcutaneous tissue. In: icd-code.de. Retrieved August 1, 2018 .

- ^ R. Dieckmann, I. Boone, SO Brockmann, JA Hammerl, A. Kolb-Mäurer, M. Goebeler, A. Luch, S. Al Dahouk: The Risk of Bacterial Infection After Tattooing. In: Deutsches Arzteblatt international. Volume 113, number 40, October 2016, pp. 665–671, doi: 10.3238 / arztebl.2016.0665 . PMID 27788747 , PMC 5290255 (free full text) (review).

- ^ Friedrich Kluge: Etymological dictionary of the German language . 21st edition. Berlin / New York 1975, ISBN 3-11-005709-3 , p. 771 (Tahitian tautau : "Signs, painting, drawing").

- ^ Deutsches Kolonial-Lexikon (1920), Volume III, p. 461.

- ↑ a b Peter Probst: The decorated body. Museum of Ethnology, Museum Education Visitor Service, Berlin 1992.

- ^ Augustin Krämer : Hawaii, Eastern Micronesia and Samoa; my second trip to the South Seas (1897–1899) to study the atolls and their inhabitants . 1906, p. 402, archive.org .

- ↑ OED : “In 18th c. tattaow, tattow. From Polynesian (Tahitian, Samoan, Tongan, etc.) tatau. In Marquesan, tatu. "

- ↑ a b tattoo artist - snake on forehead . In: Der Spiegel . No. 10 , 1951 ( online ).

- ^ Mathias Koch: About the oldest population in Austria and Bavaria. Leipzig 1856, p. 34.

- ↑ Dirty tattoo from New Year's Eve crackers. ( Memento from July 13, 2012 in the web archive archive.today )

- ^ Right Relaxed, youth website of the Federal Ministry of Justice and Consumer Protection

- ↑ Manfred Löwisch, Alexander Beck. In: Betriebsberater , 2007, pp. 1960–1961.

- ↑ For those with statutory health insurance, the health insurance company can restrict or refuse benefits in accordance with Section 52 (2) SGB V in these cases .

- ↑ Berlin's police officers are now allowed to show tattoos openly. January 5, 2018, accessed April 7, 2018 .

- ↑ Rules of practice for piercing and tattooing. Federal legal information system (RIS). Retrieved September 18, 2014.

- ↑ Can the daughter decide for herself? observer.ch

- ↑ First part: Personal law / First title: Natural persons / First section: The right of personality: Art. 16 ZGB .

- ↑ Irene Berres: 31-year-old goes swimming with a fresh tattoo - and dies. In: Spiegel Online. June 2, 2017. Retrieved June 3, 2017 .

- ↑ Since September 1, 2005, tattoo inks have been treated as cosmetics in Germany according to the Food, Consumer Goods and Feed Code (LFGB), but the Cosmetics Ordinance did not apply, as it is only for use on the skin.

- ↑ Tattooing Agents Ordinance , entered into force on May 1, 2009 ( BGBl. 2008 I p. 2215 )

- ↑ Tattoo inks: Toxic substances in two colors , test.de from July 24, 2014, accessed on October 7, 2014.

- ↑ Eva Engel u. a .: Tattoo pigments in the focus of research. In: News from chemistry. 55/2007, pp. 847-851.

- ↑ Rudolf Vasold et al. a .: Health risk from tattoo pigments. (accessible via search engine as PDF)

- ↑ Wolfgang Bäumler: The Fate of Tattoo Pigments in the Skin . (PDF)

- ↑ Jef Akst: Tattoo Ink Nanoparticles Persist in Lymph Nodes. the-scientist.com, September 12, 2017. (English)

- ↑ Tattoos pose health risks. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on June 9, 2013 ; Retrieved December 11, 2013 .

- ↑ Can't I have a PDA because of my tailbone tattoo? , accessed April 10, 2015.

- ^ William A. Wagle, Martin Smith: Tattoo-Induced Skin Burn During MR Imaging . In: AJR. 174, 2000, p. 1795.

- ↑ Andrea Hennis: Latest craze: eyeball tattoos. ( Memento from June 28, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) In: Focus Online. August 13, 2008.

- ↑ Janina Rauers: New Internet hype about eyeball tattoos ( Memento from December 29, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) . RP Online, August 15, 2008.

- ↑ Doris Kraus: Youth Culture: From Crash Diet to Eyeball Tattoo ( Memento from April 15, 2019 in the Internet Archive ) . DiePresse.com, November 24, 2008.

- ↑ a b Removing a tattoo - tattoo at www.drbresser.de

- ↑ Claus Udo Fritzemeier: Development of a new procedure for removing tattoos: Enttattooierungsstandardlösung (ETSL) . University of Hamburg, Faculty of Medicine, Hamburg 1972 (dissertation).

- ↑ Hans G. Schlegel, General Microbiology. 8th edition. Thieme 2008.

- ↑ Risks that get under the skin . Press release of the Federal Institute for Risk Assessment , August 1, 2011; Retrieved August 28, 2011.

- ↑ Medical reports in the event of poisoning . (PDF; 2.1 MB) BfR 2007, p. 28 ff .; Retrieved October 9, 2011

- ↑ Justification of the test plan. (PDF; 672 kB) United States Environmental Protection Agency , January 3, 2002 (English), accessed August 7, 2011.

- ↑ Study on the spread of environmentally-related contact allergies with a focus on the private sector . (PDF; 1.9 MB) Publication by the Federal Environment Agency , February 2004; Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- ↑ Tattoo removal: use of aqueous lactic acid . (PDF; 49 kB) Statement by the Federal Institute for Risk Assessment , August 1, 2011; Retrieved September 4, 2011.

- ↑ Permanent body jewelry - information and recommendations for protection against allergies and infections . ( Memento of September 10, 2011 in the Internet Archive ; PDF; 295 kB) German Research Center for Health and Environment , as of March 4, 2008; Retrieved July 31, 2011.

- ↑ Volker Mrasek : Tattoo Removal - Danger from Carcinogenic Substances , Deutschlandfunk - Research Current from September 15, 2016.

- ↑ In future, tattoo removal will only be carried out by a medical professional. In: aerztezeitung.de. Doctors newspaper , October 19, 2018, accessed on November 6, 2019 .

- ↑ programm.ard.de

- ↑ Original 28 January 1975. Full information of the NDR - production number 0007750128, NDR HH media accompanying map December 12, 2008 St. (1, 2)

- ↑ First published in 1933 in two episodes of the Niederdeutsche Zeitschrift für Volkskunde , published a year later as an independent publication; 1993 new edition.