Felice Beato

Felice Beato (* 1832 in Venice , † January 29, 1909 in Florence ) was one of the first photographers to document military conflicts and life in East Asia . He is known for his portraits as well as his landscape and architecture photographs in Asia and the Mediterranean region . Because of his extensive oeuvre he is one of the early photojournalists today .

More than any other photographer of the 19th century, Felice Beato concentrated on the photographic documentation of armed conflicts and conflicts. Among other things, he documented together with James Robertson the events in Russia towards the end of the Crimean War and in India after the Sepoy Uprising , and together with Charles Wirgman he reported from China about the occupation of Beijing by British and French troops in 1860.

Beato's photographs introduced Europeans and North Americans to life and events in Asia. For example, he made the first ever verifiable recordings from Korea . His photos are often the only visual documentation for events in Asia in the second half of the 19th century.

Beato's work has had a major impact on the development of photography. His influence in Japan , where he lived for more than twenty years and trained numerous photographers, was particularly long and far-reaching.

Life

origin

The origin and year of birth of Felice Beato were controversial for decades, as only a few documents are available from his early life. It was discussed, for example, that he was born in 1833, 1834 or 1835 on Venetian territory or on Corfu. (The year of birth 1824, which is also often mentioned, probably applies to his brother Antonio.)

In contrast, Felice Beato's death certificate, which was only rediscovered in 2009, shows that he was born in Venice in 1832 .

Little is known about Beato's parents. He had three siblings, including his brother Antonio and sister Leonilda Maria Martina. In Beato's earliest youth , the family moved from Venice to Corfu , which at the time was under British protectorate as part of the Republic of the Ionian Islands . From 1844 the Beatos lived in Constantinople (now Istanbul ).

Felice Beato had a British passport from the early 1860s.

The early years

Felice Beato's initial development as a photographer is unclear. Presumably he first accompanied the British photographer James Robertson to Malta in 1850 . Robertson had worked as an engraver for the Ottoman mint from 1843 and then rose to become one of the leading photographers in Constantinople. The two returned to Constantinople in 1851, the same year that Beato bought photographic equipment in Paris .

In 1853 or 1854, Felice Beato and Robertson began working together as photographers under the name Robertson & Beato . In 1854 or 1856 the two made further trips to Malta to take pictures there. Felice Beato's brother Antonio also joined in. A number of photographs from this period bear the signature Robertson, Beato and Co. , so it is believed that the and Co. refers to Antonio Beato. The bond between Robertson and the Beato brothers went beyond a purely business relationship: Robertson married their sister Leonilda in 1855.

Crimean War

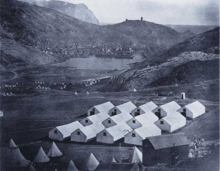

In 1855 Felice Beato and James Robertson traveled together to Balaklava in the Crimea, where, like Roger Fenton before, they photographed the battlefields of the Crimean War . Among other things, they recorded the fall of Sevastopol in September 1855. Their recordings do not differ significantly from those of Roger Fenton: Like him, Robertson and Beato were only able to take posed pictures with extras due to the bulkiness of the apparatus and the long exposure times . In contrast to Roger Fenton, who had captured a beautiful picture of the armed conflicts in the Crimean War, Felice Beato was prepared to show the cruelty of the conflicts. A total of sixty panels have been preserved, showing the chaos after the withdrawal of the Russians, the safe shelters of the Russian generals , the French trenches between the forts between Mamelon and Malakoff and above all the ruins of Sevastopol.

India

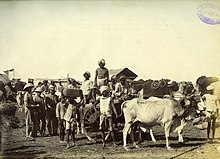

In 1857 Robertson and Beato toured Greece and also visited Jerusalem to take photographs of the locations of the Bible . They then traveled to India , probably inspired by reports of the Sepoy uprising . By the time they arrived, the rebellion was largely suppressed, but both photographers captured the aftermath of the military conflict. The most famous photos include the blown Kashmiri gate in Delhi and the photos of the Sikandar Bag defense system after the successful second siege by British troops.

Sikandar Bag, the militarily important eastern city gate of Lucknow at the time , was the scene of intense fighting between British troops and Indian insurgents in November 1857. The British dead were then buried in deep trenches, while the bodies of the Indians were left lying there. The city was later evacuated and taken again by the British in March 1858. Shortly thereafter, Beato took a picture of the skeletonized remains of Indian resistance fighters in the foreground . It is one of the earliest photographs ever to show human remains. These are supposed to have been brought in and arranged by Beato himself.

While Robertson concentrated on taking portraits in India and mainly captured members of the British army , Beato traveled to Punjab and northern India. Cities he visited include Delhi , Kanpur , Merath , Varanasi , Amritsar , Agra , Shimla, and Lahore . From July 1858 to December 1859 he was joined by his brother Antonio, but then left India, apparently for health reasons. Robertson and Beato's photos were sold through Charles Shepherd , the oldest photo retailer in India.

In 1859 Beato opened a photo studio in Kolkata , which he only ran for barely a year.

China

In 1860 Felice Beato ended the partnership with Robertson, who used the joint brand Robertson & Beato until 1867. Beato, on the other hand, joined a British-French military expedition aimed at China as part of the Second Opium War . He reached Hong Kong in March 1860 and immediately began to photograph the city and its surroundings as far as Canton . Beato's recordings are among the earliest recordings documenting Chinese life.

While working in Hong Kong, he met Charles Wirgman , who worked as an artist and correspondent for the Illustrated London News . Both accompanied the British and French troops, which landed near Pei Tang on August 1, 1860 and successfully took the fortresses of Taku on August 21. These troops reached Beijing on September 26th and captured the city on October 6th. In the weeks that followed, they devastated the Summer Palace and the Old Summer Palace . Wirgman and Beato both documented this military punitive expedition with their respective techniques, whereby Wirgman's illustrations were often based on photographs by Beato.

The capture of the fortresses of Taku

Beato's photographs of the Second Opium War are considered to be the first to document a military campaign using a sequence of dated, thematically related photographs, and thus represent the first forerunners of today's war reports. The photographs show the Taku forts and their capture by British and French troops the same approach, albeit on a smaller scale. They recount the battle in that the photographs show the approach to the fortresses, the effects of the bombing on the fortifications and finally the destruction within the fortresses. Again the photos show fallen soldiers, in this case Chinese. However, all photos were only taken after the battle, first the photos showing dead Chinese soldiers, as the dead were then buried. Only then did Beato take photographs of the area around the fortress. In the sales albums that were later offered in London, the images were then presented in an order that corresponded to the course of the battle.

Beato never photographed fallen British and French soldiers . However, the way in which the Chinese dead are depicted and how these images were created also shows the ideological aspect and the partiality of his photojournalism '. Dr. David Rennie, a member of the punitive expedition, noted in his notes:

- “ I looked around the defenses on the west side, which were littered with dead - in the north-west corner there were thirteen dead by a cannon. Signor Beato was very excited. He described the group as 'beautiful' and asked not to change them, he wanted to take some more pictures first, which was done immediately. "(Quoted from Gernsheim, 1983, p. 325)

The result of this photographic work was a representation of military triumph and the strength of the British Empire , as requested by the buyers of his pictures. British soldiers, colonial officials, merchants from the East India Company and tourists bought his paintings on site. In Great Britain, his photographs served to justify the Opium Wars and other colonial wars, and made a significant contribution to the image that the British and European public had of the cultures of East Asia.

The summer palace

During his time in Beijing, Beato also photographed the summer palaces of the Chinese imperial family between October 6 and 18, 1860. Some of these recordings are unique documents of this facility, which was one of the highlights of Chinese garden art . On October 18 and 19, the facilities were set on fire by British and French troops and largely destroyed. From the French and British point of view it was retaliatory measures for attacks on the British and French, from the point of view of the Chinese, however, the extensive looting of the soldiers in the palace complexes should be concealed.

The last pictures Beato took in China include the portraits of Lord Elgin , who signed the extension of the Treaty of Tianjin , the so-called Beijing Convention , in Beijing . Prince Kung, who countered the signature of Emperor Xianfeng , was also pictured by Beato.

Great Britain

In November 1861 Beato traveled to Great Britain. During the winter he sold 178 of his Indian and 123 of his Chinese photographs to Henry Hering, a London photographer who mainly worked as a portrait photographer. Hering reproduced the pictures and sold them on. While individual recordings were offered for seven shillings, the complete Indian series cost 54 British pounds and eight shillings, while the entire Chinese series was available for 37 British pounds and eight shillings. The average annual income in 1867 was £ 32, which shows the value that was attached to Beato's recordings.

Japan

In July 1863 Beato arrived by ship in the Japanese city of Yokohama , where Charles Wirgman had worked since 1861. The two founded the partnership Beato & Wirgman, Artists & Photographers , which was first mentioned in a list of residents from 1864 and for which house no. 24 in the foreign quarter of Yokohama was given as the company's headquarters until 1867. As before in China, Wirgman again made illustrations based on photographs by Beato, while Beato occasionally photographed Wirgman's drawings and other works.

During his time in Japan Beato created an extensive body of works. His work includes portraits , genre scenes , landscapes and cityscapes. A series of landscape photographs, which captured life and the surroundings along the Tōkai trade route , is strongly reminiscent of the work of the two Japanese woodcut masters Utagawa Hiroshige and Katsushika Hokusai . The recordings were made under difficult conditions, because visiting Japan and travel options for Europeans at that time were severely restricted by Bakufu . Beato's photographs are therefore not only remarkable for their quality, but also because they showed parts of the country that were previously unknown to non-Japanese and are among the few photographic image documents from Japan during the Edo period .

In September 1864 Beato was the official photographer of a British military expedition to Shimonoseki . The following year, he produced a number of dated views of Nagasaki and the surrounding area.

In October 1866, a fire destroyed most of Yokohama, and Beato and Wirgman also lost their studio with the negatives stored there. During the next two years Beato worked very determined to replenish his lost image inventory. The result was two photographic albums : Views of Japan contained 98 landscape and city shots, and Native Types contained 100 portraits and genre scenes in the format of 23 × 29.5 centimeters. Many of these photographs were hand colored. Beato made use of the craft tradition of Japanese watercolor painting and Japanese woodblock prints.

From 1866 on, Beato was frequently caricatured in the Japanese Punch magazine published by Charles Wirgman since 1862 as "Graf Kollodion" , which indicates both his great popularity among Westerners living in Japan and possible tensions between the two partners. The collaboration with Wirgman ended in 1867.

From 1870 to 1877 Beato was registered with his own photo studio F. Beato & Co., Photographers in house number 17 of the foreigners' quarter of Yokohama. According to a directory from 1872, his staff at that time consisted of his assistant and later manager H. Woollett as well as four Japanese photographers and four colorists. Kusakabe Kimbei , who is now considered to be one of the most important early Japanese photographers, was probably first employed as an artist at Beato before he began taking photos. Beato also worked with the Japanese photographer Ueno Hikoma and probably also taught photography to the Austrian Baron Raimund von Stillfried .

In June 1871 Beato accompanied his assistants Woollett, Tomekichi and Torakichi as the official photographer on an American naval expedition under Admiral Rodgers to Korea . The pictures Beato took during this period are the earliest documented photographs of this country and its people.

Beato did not limit his business activities to photography. In addition to several photo studios, he also owned land, worked as a broker and partner in the Grand Hotel in Yokohama, and traded in imported carpets and handbags . During his stay in Japan, he is said to have lost large sums of money several times through speculation and unfavorable deals. On August 6, 1873, he was appointed Consul General of Greece in Japan (which could be an indication that he was actually born in Corfu).

On January 23, 1877 Beato sold the majority of his photographic inventory to the company Stillfried & Andersen , which also took over his studio in Yokohama. In 1885 this company sold the stock to Adolfo Farsari .

In the following years Beato concentrated mainly on his professional activity as a trader and was also active as a speculator . On November 19, 1884, he left Japan for Port Said , Egypt . According to a report by a Japanese newspaper on December 5, 1884, he had lost all of the fortune he had acquired on the Yokohama silver market through speculation on the Tokyo rice market, so that the travel expenses had to be paid for by a friend.

The late years

From 1884 to 1885 Beato was the official photographer of a military expedition led by GJ Wolseley to Khartoum , Sudan . The aim of the unsuccessful expedition was to end the siege of General Charles George Gordon by the Mahdi uprising .

Afterwards Beato stayed briefly in England. On February 18, 1886, he gave a lecture on photography at the London and Provincial Photographic Society , which was published on February 26, 1886 in the British Journal of Photography .

In 1888 Beato was again active in Asia and toured Burma . He opened a photography studio in Mandalay in 1889 and a furniture and handicraft shop in 1895, which quickly became an attraction for foreign visitors. Customers all over the world received an order catalog by mail on request, with each item having a photograph, a detailed description and a price. The catalog could be filled out and returned, an unusually modern business method for the time. Two of these catalogs are still in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London . As early as 1898 Beato sold his company to the former military officer Maitland Fitzroy Kindersley, who until it was dissolved in January 1907 under the old name “F. Beato & Co. ”continued.

Little is known about the last years of Felice Beato's life; it is possible that he ended his photographic activity after 1899. The Rangoon Gazette reported on January 30, 1899 that Beato was in Rangoon . A letter to the editor published on November 15, 1902 in the Times of Burma then mentioned that Beato had left the country. Beato then settled in Italy, where he received regular payments under an agreement with the British consul. He died in Florence on January 29, 1909 .

Problems with the assignment of the works

On the basis of a series of photographs bearing the signature Felice Antonio Beato and Felice A. Beato , it was long suspected that Beato succeeded through intensive traveling to capture events that took place around the same time in places as far apart as Egypt and Japan played. However, Italo Zannier was able to prove in 1983 that Felice Beato occasionally worked together with his brother Antonio (* around 1825, † 1903), who ran photo studios in Cairo from 1862 and in Luxor from 1872 , and that both brothers marked their negatives in the same way. This prevents a clear assignment of some pictures to one of the two brothers.

However, there are a number of other difficulties in assigning the photographs. When the company Stillfried & Andersen Beatos took over the photographs, it followed the common practice among photo dealers of the 19th century and resold the photographs under its own name. It themselves and some of the buyers modified Beato's recordings by putting numbers, company names and other inscriptions on the negative or print. They created hand-colored versions of the recordings that Beato did not have his employees colorize. This has led to the fact that recordings by Felice Beato are ascribed to the company Stillfried & Andersen to this day.

Fortunately, Beato signed and inscribed many of his prints in pencil or ink on the back. Once these prints have been drawn up, the inscriptions can occasionally be read through the thin paper with the help of a mirror. This often not only enables us to determine what the picture shows and when it was taken, but photo historians can also clearly identify Felice Beato as the author.

Beatos techniques and influence on photography

From the middle to the end of the 19th century, the technical possibilities of photography were still very limited. In the 1850s, Beato mainly used albumin plates (glass plates coated with light-sensitive silver salts), with which negatives could be produced that came close to daguerreotypes in terms of their brilliance and delicacy . Such albumin plates could be prepared long before they were actually used: For example, Beato photographed the consequences of the Indian Sepoy uprising in 1857 with plates that he had coated a few months earlier in Athens. However, albumin plates only had a low sensitivity to light. When using a lens with a long focal length and a light intensity of f / 52, Beato initially required an exposure time of up to three hours even for well-lit objects. However, according to his own statements, he succeeded in reducing this time to four seconds by developing the plate for several hours in a saturated gallic acid solution. However, he did not publish this technique until 1886, when photography with albumin plates was already obsolete, and it was strongly contested by experts. Despite repeated inquiries, Beato failed to provide evidence of this recording and development technology.

Felice Beato's achievement is to have produced excellent photographs within the framework of the possibilities at the time. In addition to purely aesthetic considerations, it was also the long exposure times at the time that led Beato to carefully place the objects in his photographs, especially in the studio and with carefully composed portrait photographs . The well thought-out placement of locals as aesthetic-decorative accessories in front of buildings and landscapes, in order to underline their effect accordingly, is characteristic of his pictures. In the shots in which this was irrelevant to him, both people and other moving objects can often only be seen as blurred spots because of the long exposure times. However, these blurry spots are also a common technical feature of photographs from the 19th century.

Beato later mainly produced prints of wet collodion plates on albumin paper . Like other photographers of the 19th century, he often photographed his own originals. The original was attached to a solid surface with needles and then photographed so that further prints could be made from a second negative . The pins with which the original was attached can occasionally be seen on the copies. Despite the loss of quality, it was an effective and economical way to reproduce photographs at the time. Beato is also one of the pioneers of hand-colored photographs and panoramic photography . The idea of coloring photos probably came from a suggestion by his temporary partner Charles Wirgman. But it is also possible that he saw colored photos of Charles Parker and William Parke Andrew . The coloring of landscapes is reserved and naturalistic. The portraits are often more heavily colored, but are also considered excellent works.

During his entire photographic career, Beato has repeatedly created spectacular landscape photographs in the form of panoramic photographs . To do this, he took several coherent shots of a scene and linked the prints together so that there were no overlaps. In this way he managed to convey a feeling for the vastness of a landscape. His panorama of Pehtang , which consists of nine individual shots that merge seamlessly and have a total length of 2.5 meters, is considered particularly successful .

Felice Beato is particularly significant for the Japanese history of photography . He was the first to introduce the standards of European studio photography in Japan, thereby significantly influencing numerous Japanese colleagues.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Terry Bennett: History of Photography in China, 1842-1860 . London, 2009, p. 241

- ↑ Astrid Erll: Prämediation - Remediation. Representations of the Indian uprising in imperial and post-colonial media cultures from 1857 to the present. Trier 2007. page 84.

- ^ Anne Lacoste: Felice Beato - A Photographer on the Eastern Road . Los Angeles, 2010, pp. 188–189 (facsimile of the original catalog by Henry Hering, with a detailed list of the individual motifs)

- ↑ Francoise Heilbrun in Michel Frizot (ed.): A New History of Photography . Könemann, Cologne 1994/1998, ISBN 3-8290-1328-0 , p. 161

literature

- Astrid Erll: Premediation - Remediation. Representations of the Indian uprising in imperial and post-colonial media cultures (from 1857 to the present) . WVT Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier, Trier 2007, ISBN 978-3-88476-862-4 .

- Helmut Gernsheim : History of Photography - The First Hundred Years . Vienna, 1983, ISBN 3-549-05213-8

- Helmut Gernsheim: The Rise of Photography, 1850-1880, The Age of Collodion . London, 1988, ISBN 0-500-97349-0 (English)

- Nissan N. Perez: Focus East. Early Photography in the Near East, 1839-1885 . New York, 1988, ISBN 0-8109-0924-3 (English)

- Claudia Gabriele Philipp, Dietmar Siegert and Rainer Wick (eds.): Felice Beato in Japan - Photographs at the end of the feudal period 1863–1873 . Heidelberg, 1991, ISBN 3-925835-79-2

- Terry Bennett: Early Japanese Images . Rutland Vermont, 1996, ISBN 0-8048-2029-5 (English)

- Beaumont Newhall: History of Photography . Munich, 1998, ISBN 3-88814-319-5

- Carsten Rasch: Photographs from ancient Japan - Felice Beato and his photographs from the Edo era . Hamburg, 2014, ISBN 978-3-738-60700-0 (English)

- David Harris: Of Battle and Beauty. Felice Beato's Photographs of China . Santa Barbara, 1999, ISBN 0-89951-101-5 (English)

- Vidya Dehejia: India through the Lens - Photography 1840-1911 . Washington DC, 2000, ISBN 3-7913-2408-X (English)

- John Clark: Japanese Exchanges in Art, 1850s to 1930s with Britain, Continental Europe, and the USA. Papers and Research Materials . Sydney, 2001, ISBN 1-86487-303-5 (English)

- Sebastian Dobson: I Been to Keep Up My Position: Felice Beato in Japan, 1863-1877 . In: Nicole Coolidge Rousmaniere and Mikiko Hirayama (Eds.): Reflecting Truth: Japanese Photography in the Nineteenth Century . Amsterdam, 2004, ISBN 90-74822-76-2 (English)

- Anne Lacoste: Felice Beato - A Photographer on the Eastern Road . Los Angeles, 2010, ISBN 978-1-60606-035-3 (English)

Web links

- Boston University Art Gallery. 'Of Battle and Beauty: Felice Beato's Photographs of China'

- Griffiths, Alan. 'Second Chinese Opium War (1856-1860)', Luminous-Lint

- Nagasaki University Library; Japanese Old Photographs in Bakumatsu-Meiji Period, sv "F. Beato "

- Japan photos by Felice Beato in the Digital Gallery of the New York Public Library

- A complete album by Beatos on the sights of Japan with original annotations

- A complete album of Beatos on Japanese culture with original notes

- Literature by and about Felice Beato in the catalog of the German National Library

- Entries in Arthistoricum.net

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Beato, Felice |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Beato, Felix (English) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Italian photographer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1832 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Venice |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 29, 1909 |

| Place of death | Florence |