Prostitution in Japan

Prostitution in Japan has a comparatively varied history. The Anti-Prostitution Act of 1956 officially prohibited sex for a fee. However, there are still various ways of circumventing the ban, such as anal , oral or thigh intercourse ( 素 股 Sumata ). In the past, prostitution flourished primarily through its association with widely used arts such as music and dance. Today, however, it is illegal and only practiced more or less covertly.

Disambiguation

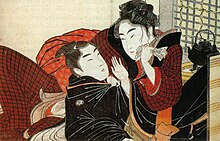

When speaking of prostitution in Japan speaks, you have to move away from the understanding of the West of this term: Unlike the Christian dominated world view prostitution was not brought into Japan in conjunction with shame or sin , but influenced by other morality. Accordingly, courtesans enjoyed prestige and recognition. When looking for a European equivalent, they could best be compared to the Greek hetaerae . The terms “courtesan” and “prostitute” are used rather indiscriminately and arbitrarily in the literature, as there is no generally accepted criterion for a separation. In order to understand prostitution in Japan, it is necessary to consider the customs and views of pre-modern Japanese society. Utagaki is an example of the differentiated understanding of sexuality of the people of this time.

Utagaki (歌 垣 , alsoread kagai ) was a festival of ancient origin (first mentioned in 498), which was celebrated before and during the Nara period (710–794). On the occasion of shrine festivals in spring and autumn, the young people gathered in rural areas on mountain peaks or coastal beaches. They sang, danced, ate, drank and exchanged poems. This tradition probably emerged from fertility rites. Utagaki (literally song hedge) was a kind of song contest in which boys and girls competed in groups or in pairs. Poems and songs were read to each other, often improvised, and thus encouraged others to respond with another poem. After drinking plenty of rice wine while dancing and singing, the choice of partner was easier. When a couple found each other in a competition, they usually spent the night together. Utagaki was carnival-like in nature, and things were allowed at these festivals that were otherwise forbidden. It was an exception to find one's partner in this carefree way and to practice free love so openly. Acting out sexual acts has been closely associated with the arts of music, singing and dancing. It was normal and natural for a dancer to show her affection to her admirer in this way and was therefore not viewed as contemptuous. Women who did this job were often referred to as otome (乙 女 ), which means “single girl” or “miss”. They were by no means directly referred to as courtesans or prostitutes. In Manyōshū , the first large collection of Japanese poems,the kanji 遊行 女 婦 were givenfor the term “ courtesan ”, which literally means “women who entertain”. However, there are two readings for this: asobi and ukareme . It is unlikely that there were two terms for the same thing, rather two different types of courtesans.

Ukareme

Ukareme (浮 か れ め ) were women who were not entered in the tax register and had no permanent residence. Therefore, in the eyes of the authorities, they did not exist. The term can be traced back to the ukarebito (浮 か れ 人 ), who were magicians and jugglers who roamed the country. They may havecome to the Japanese islandsfrom Korea .

The women of the ukarebito were mostly actresses and courtesans at the same time. In contrast to the asobi , there is no reference to artistic activity among the ukareme and therefore this term has a rather derogatory connotation (“servants, vagabonds”). It was not until the 11th century that they were able to learn courtly arts and achieved similar qualities as other entertainers ( asobi ) of that time.

Asobi

Asobi (遊 び ) is the short form of asobime (遊 び 女 ) and the name of the Nara period for courtesans. They mastered the arts from courtly tradition and entertained nobles in their provinces. In contrast to the ukareme , they are given a better reputation because they were not just prostitutes, but rather talented entertainers.

Beginnings of prostitution

The beginnings of the history of Japan are generally presented mostly in the form of legends. It is no different with prostitution. It was not until the 8th century AD that there were first written documents that mention courtesans and provide information about their position in society and their behavior. The origin of prostitution is much earlier, however, scholars are not sure when exactly. Either he began with the miko , servants at Shinto shrines , or the uneme , entertainers of the emperor.

What has been proven, however, is that in very early times sexuality was celebrated in various religious ceremonies and festivals and wandering women associated with magic and religion made a living from dancing, storytelling, medical skills, fortune telling and sometimes prostitution earned. These celebrations likely served as fertility rites in rural Japan.

It is also unclear what social status prostitutes had, whether they were exploited and discriminated against or whether they were fully integrated into society and, in some cases, rich and powerful. The dominant view is that courtesans broke norms and resistance and criticism developed very slowly when there were women who only practiced prostitution and thereby threatened social stability. Above all, abstinent monks tried to convince courtesans of honest and honest work. In their descriptions, prostitutes are portrayed as very repentant because they should be redeemed through trust and belief in Buddha . Relatively few women will have gone this way, because it was easier for them to carry out their old job.

However, it is very likely that prostitutes were not ostracized or marginalized, but that there were both proponents and opponents of prostitution.

Miko

Miko (巫女 or神 子 ) are women who work at Shinto shrines or who traveled around the country and practiced their practices there. In Shintō , single and virgin girls have a special religious function: They are servants of the gods (神 kami ), since they are the ritually purest beings. As mediators between gods and humans, they should always remain chaste, but this commandment was not strictly observed everywhere: high priests could also sleep with them unhindered. Then the miko became something like a “God-Mother”, because the child born from this connection was considered a divine mystery . With the birth of a child she was unable to continue working in the temple, and so she went (back) to the city to earn a living elsewhere.

The belief that virginity is restored with each menstruation , no matter how many men she had slept with, helped the priestesses to stay in the shrine if they did not become pregnant.

Working as a miko entailed major economic risks: She had to break free from her family and community ties through her service for the shrine and thus no longer had a secure income. With the introduction of Buddhism in the 6th and 7th centuries and the onset of the organization of the shrines, more and more miko went on a wandering ( 歩 き 巫女 aruki miko = wandering miko ) in order to sell their services for money, since they had their position at the Had largely lost shrines. Many miko felt compelled to learn other services in order to be able to continue to earn their living: Most of the courtesans took over the arts of the higher society when the temptation or their need became too great. As a result, they could also engage in prostitution.

Uneme

Until historical times, it was the custom for provincial rulers to send their daughters to the imperial court as a sign of their loyalty. These young and pretty girls were called uneme ( 采女 ). They were accepted into court service and served the personal waiting of the emperor, especially during the Yamato period . This enabled them to gain the ruler's favor and establish advantageous relationships at court, which was often beneficial to the family's power. The origin of this tradition probably goes back to the ritual sacrifice of people to the gods who asked for protection.

With the Yōrō Code of 718, the status of all subjects was regulated by law and family members could no longer be enslaved, given away or sold. This created a great deficit in the circles of the nobles, because it was expected of a nobleman to have a certain number of concubine wives, sisters and daughters. This gap was filled by women who specialized in the required services: comprehensive care for men with all entertaining and sexual tasks for a certain fee.

Terms

Naikyōbō and jogaku

In the Nara period , Japan took over many of the achievements of China to make up for arrears and become a match. In terms of entertainment, too, they wanted to offer foreign guests and embassies the same comfort as in their home country. Then the naikyōbō was founded, an authority for the musical arts at court. The model for this was the Chinese jiao fang , which was an institute for the training of courtly entertainers.

The girls in naikyōbō (lit. local jiao fang ) were called jogaku ( 女 学 ), and since they should be pretty and young, it could be about uneme (imperial servant). In contrast to the Chinese palace courtesans ( gongji ), it was not possible to give away jogaku or let them do any service. They were ladies-in-waiting whose artistic appearances were limited to certain occasions and who, like courtesans, did not have to make a living with it. Jogaku of noble origin often served the emperor alone.

At the beginning of the 9th century, the naikyōbō lost its importance, because with the move of the imperial court from Heijō-kyō (today's Nara ) to Heian-kyō (today's Kyōto ), relations with China waned and a time of national sentiment began.

Asobime

Asobime (遊 び 女 ) is the name of the courtesans of the Nara period (710–794), and their name means something like "playmate". They were entertainers at parties of the court nobles, played songs, had meaningful conversations, learned courtly behavior and thus had a certain level of education. They were influenced by thearts taughtat the naikyōbō (office for entertainers of the imperial court), but in contrast to the jogaku (court entertainers) they were not active at the ruler's palace, but in the remote provinces of the nobility. They offered the posted officials a replacement for their wives who were not present, because both the nobles and the asobime themselves wanted a more capital city atmosphere in the rural areas. Soon the professional entertainers in the provinces were on par with the ladies-in-waiting in Yamato . There they had a kind of "temporary marriage" as long as their patron stayed in the country. A courtesan also took on any domestic work, because that was part of the duties of a wife. If an uneme was released from her service as the emperor's servant, all she could do was go back to her homeland andcontinue to workthere as an asobime . In this way she continued to take part in the glamorous life of the wealthier population, was able to earn a living and enriched the otherwise provincial behavior of the officials, who often looked for a change during their stays in the country. Her entertainment skills were aimed at both men and women, from whom they received applause and gifts. The entertainment districts in the cities were primarily for the entertainment of the elite, while in the country there was enough demand to call their profession a real business. They mostly performed on the water, in small boats they approached their future customers and seduced them with their colorful dresses (similar to those of young nobles) and their singing. On the coasts and river banks they entertained guests in inns or were invited by them to receptions and festivities at the court. The Yodo Riverbetween Kyoto and the Pacific was aparticularly populararea for the asobi .

Asobi often organized themselves and had men only as patrons. A head was elected from among them ( mune or so ), or the richest woman ( 長者 chōja ) of the group took this position. The pay was the same for everyone, but could be higher for the chōja . The extent was subject to their customers. They never kept their birth names, but always gave themselves stage names with ritual connotations . Many women have been drawn into this trade through adoption or fictitious kin. Little is known about recruiting new women in general; it may have been a possible option for women who no longer had a place in the family system (death of their husbands, bankruptcy , political failure).

Shirabyōshi

Shirabyōshi (白 拍子 ) were high-class artists who specialized in dancing. Originally, this term referred to a dance and song performance that became popular in the 12th century and had a distinctive rhythm. Later the female artists of this dance were also called that. Where the name comes from is unknown: Possibly from the beat ( shirabyōshi ) of the drum thataccompanied Buddhist chants (声明 shōmyō ). However, the term was later written exclusively with the Kanji for the color white (白 shiro ) and the word rhythm (拍子 hyōshi ), referring to the white robe of the shirabyōshi , which wassimilar tothat of a miko .

Characteristic of shirabyōshi was her male clothing:

- Long, red hakama 袴 (mainly worn by men)

- Red and white suikan (robes of Shinto priests)

- ebōshi 烏 帽子 (black lacquered priest hat)

- Tachi 太 刀 (sword of a samurai )

- kowahori (fan)

They covered her entire face with white make-up and traced her eyebrows a little higher. Her long, black hair was tied loosely with a takenaga (hair band). The male behavior and appearance of the shirabyōshi should show the erotic image of a transformed, androgynous human being. Their appearances were determined by dancing and singing ( 今 様 歌 imayō uta ) and the use of fans , flutes, cymbals or small hand drums ( 鼓 tsuzumi ). Imayō uta ("songs of the modern kind") were pieces of music of Buddhist origin of mostly four lines (7-5-7-5-syllable verses), which were largely neglected by the noble society. Their content could have religious significance as well as address profane issues. Occurred shirabyōshi at the imperial court, at parties of nobles and Buddhist and Shinto temples during ennen mai 延年舞 (small ceremonial plays). The most important dances were the midare shirabyōshi 乱 れ 白 拍子 (danced by many dancers) and the futari mai no shirabyōshi 二人 舞 の 白 拍子 (performed by two dancers). They were originally male dances ( 男 舞 otoko mai ) that were performed to old songs ( 歌 謡 kayō ). Although some Shirabyōshi were lovers of prominent men and gave birth to their children, it was primarily not their job to engage in sexual activity. They were primarily artists. Their most successful period was in the 12th and 13th centuries, after which their popularity declined and they were supplanted by the kusemai dances.

Kugutsu

In the Heian period, the term kugutsu ( Japanese 傀儡 ) was used to describe a non-settled group that may have immigrated from the mainland. They kept their traditional way of life for a long time, lived in tents made of animal skins, were divided into clans and did not obey regional princes. Since they did not farm, they were not under rural authority and did not pay taxes. The men were gifted in archery on horses and fed their families on the hunted prey. Kugutsu were also good at magic and juggling skills (swinging swords, juggling balls) and making puppets. The women ( 傀儡 女kugutsume ) were often active as singers and enticed strangers to sexual pleasures with seductive songs.

In descriptions they are compared with the Xiongnu ( Huns ), nomadic equestrian peoples in central China at the time of the Han dynasty . But they differed from the yūjoki ( 遊 女 き ), who were magical artists and are said to have had relationships with the Heian elite. There was no clear separation between asobi and kugutsu and often both terms were used interchangeably, as both asobi and kugutsu specialized in dance and imayō poems. In contrast to the asobime , kugutsume mainly traveled between different inns on busy routes .

During the Kamakura period , they received compensation in the form of money because they could not farm any land. Ukarebito were among the shokunin ( 職 人 = artisans) and thus had recognized rights and obligations, for example towards the shirabyōshi or asobime . They were now allowed to own land and to file a complaint in the event of grievances.

Sexuality during the Heian Period

Polygamy and marriage

In the Heian period the term “marriage” was fluent because most families consisted of polygamous relationships with several public partners. There were long-term relationships and short-term affairs (it was not normal to bond with low-society women for long periods of time). Under certain circumstances, however, it was possible that the man extended the relationship with his courtesan and also recognized the children that resulted from it. Tolerance and openness made it possible to maintain this system, but it was also common to take personal advantage of connections with higher-ranking officials or nobles. A man usually had a main wife of high status, with whom he was married, and several lower wives. He could not easily part with his wife ( 北 の 方 kita no kata ), but the concubines were always exposed to his benevolence. All women often lived in the man's house ( virilocality ) if it was affordable. The kita no kata should not feel jealous of her husband's concubines. She would also have accepted and recognized a child of theirs if she could not have children herself. There was great competition among the concubines because they always had to expect to be abandoned for someone else and thus to live without financial support. It was common for only men to change partners often, but in theory it could be the same for women. As a result, neglected concubines often had several lovers. A wife, however, was expected to be faithful to her husband, and he was allowed to kill her if he saw her inflagranti with another man. Even widowed women should not look for a new husband. But one cannot say that a man thought his wife was inadequate and therefore had concubines. She fulfilled all duties in society, had demeanor and beauty, and was educated. The conjugal bond at that time did not have the same value as in Christianity .

Polygamy was not a sign of licentiousness; it was what set the "good people" apart from the common people. Monogamy was meant for those who could not otherwise afford it. According to Confucianism , it was a duty to maintain one's lineage as well as possible because of illness and high death rates. Regular intercourse with a woman lowers her yin essence, which can lead to death. Without life-giving yin , the man is also weakened and would die, because in the male belly, female yin is converted to male yang . Therefore, a woman must not serve her partner sexually too often. If a man sleeps with many women, he can prevent this condition, but he should avoid ejaculation . This is better for the state of health: It strengthens vital forces, heals diseases and improves the senses to the point of immortality. Exactly how a man follows this rule depends on his personal ability ( ejaculating three times and having intercourse ten times is acceptable). By preventing ejaculation , the man protects his yang because it stays in the body. The female climax is more important for healthy sex as it feeds yin to the man . Foreplay stimulates the woman's yin through the mutual exchange of tenderness and sets it in the mood so that it can flow better. Therefore, caresses have to be especially loving. Also cunnilingus is particularly productive for the man, because that he can yin record directly from its source.

Adultery

The Kamakura shogunate did not see rape and kidnapping as serious violence and therefore did not consider it necessary to control these offenses. It was not until 1232 that in the 34th article of the general code of bakufu ( 御 成敗 式 目 goseibai shikimoku ) adultery was made legally punishable: “Secret meeting” ( 密 会 mikkai ), regardless of whether the woman involved was forced or consented to it, cost both participants half of their shōen ( fiefdom ). The harm done to a woman by rape did not matter because in both cases it was a violation of the husband's exclusive right over his wife as a sexual being. The woman's body was only a means of bafuku to restore state authority, and she was responsible for protecting her husband's property, that is, her own body. As head of the family, the man had both the authority and the right to demand obedience from those under him. Who contributed to the prosperity of the house was important. So does the woman in her role as mother of his children, who were important for the maintenance of the lineage.

In the year 1263, the decisive distinction between rape ( 強姦 gōkan ) and willful adultery ( 和 姦 wakan ) was made for the first time in an imperial code . The perpetrator should therefore pay two kanmon and the raped woman nothing. With mutual agreement, both had to pay a total of two kanmon , divided in equal parts. It was also true of a woman who had seduced another man, because then she paid the fine and not he. The sanctioning of the man involved was intended to prevent possible revenge by the husband. However, that rarely prevented him from taking further retaliation . The separation into rape and willful cheating is due to the Yōrō-Codex ( 養老 律令 ), in which one year imprisonment for premarital sex and two years imprisonment for adultery were set. If a woman was coerced, she was not responsible and was not punished. Over time, the shogunate (Japanese: bakufu) paid less and less attention to this subdivision and soon extramarital sex was referred to only as kaihō (hugging), totsugo (having sex) and kan (hurting). The participation of the woman was irrelevant, since only the distribution of punishment and the maintenance of social order were of concern. It was only after the Ōnin War (1467–1477) that the code had to be changed, as there was almost an incident that led to new conflicts. The new treatise paid even less attention to the female body, because with it the distinction between forced and wanted sex was abolished and everything was now only "secret", i.e. illegal. In addition, the betrayed husband was allowed to take revenge directly: Either outside his home - then he had to kill his wife too, to make it clearly look like revenge and not just like a normal murder - or inside his home, then he could spare his wife. Supported by the traditional practices of retaliation, the bakufu no longer saw itself responsible for punishing the perpetrator. There were also shameful punishments for women: for example, cutting off her hair marked an adulteress as unworthy and no one would be interested in her as long as her head of hair had not grown back.

Yobai

The choice of partner has historically been relatively free in the country and less externally determined than in the upper class or among urban citizens. According to myths, a woman is said to have slept with a man and then asked her parents for permission to marry. Love was the prerequisite for a common future, not virginity. This Shinto tradition was practiced in some rural areas of Japan until shortly after World War II. Yobai ( 夜 這 い = "window") was a possibility to choose your future partner and to visit her secretly at night to make her a wife. The term comes from the verb yobu ( 呼 ぶ = “to call”, also in the sense of “to call someone to you”), but was later written exclusively with the Kanji for “night” ( 夜 ) and “crawl” ( 這 ). On the occasion of various festivals (rice-planting ceremonies, fertility festivals) the Bachelor of a village met ( 若者組 , wakamono-gumi , dt "young men frets.") In the largest of its group or in a special property - the wakamono-yado ( 若者宿 ) - and then roamed the streets. Whoever won the “ rock-paper-scissors ” game was allowed to sleep with the girl in the respective house. When entering the foreign property, they kept quiet and left their bed at night before daybreak. In their own interest they both covered their faces with scarves so that they would not be recognized, especially if the young woman refused her nocturnal visitor. It was normal to ignore the girls' feelings in this, as this matter was decided by the judgment of the men. In some cases it was almost rape , but it was said that girls who had never been selected at yobai would never have a husband either, because no one wanted them because they were afflicted with diseases, a curse or other deficiencies could. The parents mostly discreetly ignored this cruelty. It was not uncommon for abortions and sudden infant deaths to occur . Nevertheless, the children born were a welcome worker in the village, even if paternity was often not clear. In villages with marriage-like relationships, children were raised together and it didn't matter who they came from, only that they ensured the continued existence of the village community. In a few cases, girls have alerted their fathers if they did not like the man, and the man has driven him off the property. However, if a daughter repeatedly rejected one or more young men, she was excluded and despised by the village community. It was a freak of nature ( 片 輪 物 katawa mono ). Since neither a wedding nor the exchange of rings distinguished the future couple, they could only be recognized as a married couple when their child was born and they had their own house or apartment. That way, it was easy to break up, because then the bond was simply broken without any divorce proceedings. Yobai took place very early, mostly after young girls had their first menstruation (around the age of 15) and thus became fertile. Because of the short life expectancy, it was necessary to get married early and have children.

Virginity was considered a low priority at the time and didn't play a huge role in partner choice. So it came to ritual defloration in the rural areas of Japan, performed by a priest or the father with a phallus- shaped stick. In contrast, sexual inexperience was not considered a virtue; a woman with practice was valued. But girls also offered themselves to young people as soon as they were sexually mature. This behavior did not count towards yobai , but was called ashi ire ( 足 入 れ = put your feet in). A woman went to the house of her chosen one and showed how reliably she could do all domestic chores. She should get on well with his parents and also be able to help with field work. From the 17th century onwards, marriage habits solidified and wives moved into their husband's house ( virilocality ) and did not stay with their parents ( patrilocality ). As a result, yobai has become more of a folk tale than a widespread practice.

Prostitution during the Edo period

With the short-term move of the imperial capital from Kyoto to Edo (today's Tokyo ), there was a strong economic boom. Together with the bakufu government of the Shogun , numerous nobles, officials and servants had to go along, most of whom left their wives and children in the old capital of Kyoto or on their homeland in the country. The fact that the new capital was marked by a clear surplus of men led to the formation of a large joyous district, the Yoshiwara .

During this time the Oiran (Edo) and Tayū ( Kyōto , Osaka ) emerged.

With the aim of joining the Western powers and being recognized as modern by them, Japanese legislation largely adopted Western, especially German, rules and thus also moral concepts. Ultimately, prostitution was banned in Japan in 1956 by the Anti-Prostitution Act (売 春 防止 法, Baishun Bōshi Hō; also Act No. 118 of May 24, 1956).

Today's forms

Due to the legal situation, various alternatives to open prostitution with vaginal intercourse have developed, some of which seem quite bizarre by European standards. These are usually referred to with English-sounding euphemistic fantasy names.

Some of the most important alternatives for initiating prostitution are:

- Telephone Club ( テ レ ク ラ terekura ) are telephone-based dating agencies which, for a fee, establish the mediation between potential clients and private ladies.

- Fashion Health ( フ ァ ッ シ ョ ン ヘ ル ス fasshonherusu , mostly abbreviated as ヘ ル ス herusu ) are facilities in which customers are mainly satisfied orally.

- Image Club ( イ メ ー ジ ク ラ ブ imējikurabu , abbreviated イ メ ク ラ imekura ) are fetish-oriented special forms of "health".

- Delivery Health ( デ リ バ リ ー ヘ ル ス deribarīherusu , abbreviated デ リ ヘ ル deriheru ) stands for call girls who offer hotel and home visits with oral sex, but often also with vaginal sex for a special fee .

- Soap Land ( ソ ー プ ラ ン ド sōpurando ) are massage parlors that officially cleanse the body, including genitals, for the purpose of satisfaction.

The Japanese hostess clubs must be clearly distinguished from prostitution and brothels. These are bars where hostesses entertain their customers for a fee. However, the entertainment is limited to joint conversations, social drinking, karaoke and the like.

The traditional Japanese geishas are a kind of educated entertainers. They are often mistakenly seen as noble prostitutes, but sexual acts between a geisha and their customer are and have always been absolutely taboo and impossible.

Enjokosai

A social phenomenon is the large number of young girls (around ten percent according to some surveys), which mostly affects middle or high school students who offer themselves for enjokōsai ( casual prostitution ). However, this does not necessarily have to involve sexual acts.

After the economic bubble burst in the 1980s, this phenomenon spread particularly quickly in large cities after many people had lost their jobs and the girls wanted to supplement their pocket money in order to be able to finance their normal leisure life . Today, financial hardship is no longer the main reason, but the fact that high school girls' prostitution is well known and nothing is being done about it. The police rarely intervene and it is sometimes difficult to identify the girls' intentions, because sometimes contact is made in the park simply by distributing offers to "massage" or "go for a walk". Family neglect and broken relationships are a cause, but sometimes the girls just sell themselves “because everyone else does it too” and a good 200-350 € can be earned with a few hours in a Love Hotel where other student jobs can't. The girls can also find their customers via so-called “ telephone clubs ” or certain websites. Minors have been banned from accessing such intermediary websites since 2003, but the lack of supervision makes it easy for them to register anyway.

See also

Web links

literature

- Nicholas Bornoff: Pink Samurai: Love, Marriage and Sex in Contemporary Japan. Pocket Books, New York 1991.

- Janet R. Goodwin: Selling Songs and Smiles: The Sex Trade in Heian and Kamakura Japan. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu 2007. In Monumenta Nipponica - studies in Japanese culture. Volume 55, No. 3, Sophia University Press, Tokyo 2000.

- Terry Kawashima: Writing Margins - The Textual Construction of Gender in Heian and Kamakura Japan. Harvard University Press, Asia Center, Cambridge and London 2001.

- Howard S. Levy: Sex, Love, and the Japanese . Warm-Soft Village Press; Washington 1971.

- Douglas C. McMurtrie: Ancient Prostitution in Japan. Kessinger Publishing, Whitefish, Montana 2005. In: Lee Alexander Stone (Ed.): The Story of Phallicism Volume 2. Pascal Covici, Chicago 1927.

- Katherine Mezur: Beautiful Boys / Outlaw Bodies: Devising Kabuki Female-Likeness. Palgrave Macmillan, New York 2005.

- Benito Ortolani: The Kabuki Theater - Cultural History of the Beginnings. Sophia University Press, Tokyo 1964.

- Rajyashree Pandey: Women, Sexuality, and Enlightment: Kankyo no Tomo. In: Monumenta Nipponica - studies in Japanese culture. Volume 50, No. 3.Sophia University Press, Tokyo Autumn 1995.

- Pierre Francois Souyri: The World Turned Upside Down: Medieval Japanese Society. Authorized translation by Käthe Roth, Columbia University Press, New York 2001.

- Stein, Michael: Japan's courtesans. A cultural history of the Japanese masters of entertainment and eroticism from twelve centuries. Iudicium, Munich 1997.

- Masayoshi Sugino: The beginnings of Japanese theater up to the no-play. In: Monumenta Nipponica - studies in Japanese culture. Volume 3, No. 1.Sophia University Press, Tokyo 1940.

- Hitomi Tonomura: Re-envisioning Women in the Post-Kamakura Age. In: Jeffrey P. Mass: The Origins of Japan's Medieval World. Courtiers, Clerics, Warriors, and Peasents in the Fourteenth Century . Stanford University Press, Stanford 1997.

- Hitomi Tonomura (Ed.): Women and Class in Japanese History . University of Michigan, Center for Japanese Studies, Ann Arbor 1999.

- Tresmin-Trémolières: Yoshiwara. The love city of the Japanese . Authorized translation by Bruno Sklarek, Louis Marcus, undated, Berlin 1910.

- Roger Walch: Sex Education in Japan . In: Asian Studies. No. 4, Verlag Peter Lang, Berlin / Frankfurt am Main / New York / Paris / Vienna 1997 (PDF file, 996 kB)

- Yamazaki Tomoko: Sandankan brothel No. 8. Iudicium, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-89129-406-9 . (Japanese orig. 1972)

Individual evidence

- ↑ e-Gov 法令 検 索. Retrieved November 23, 2019 .

- ↑ Mineko Iwasaki: The True Story of the Geisha . 3. Edition. Ullstein Taschenbuch, 2002, ISBN 3-548-26186-8 , pp. 347 .

- ↑ a b Christine Liew: Can it be a little longer? - Hot Beloved Love Hotels. Shadow runners and pearl girls - everyday adventure in Japan. Dyras, Oldenburg 2010. pp. 199-203. Print.

- ↑ [1] Lars Nicolaysen: Lolita boom in Japan: Thousands of school girls offer "part-time jobs". N-tv.de. IP Deutschland GmbH, May 21, 2015. Web. January 27, 2017. < http://www.n-tv.de/panorama/Tausende-Schulmaedchen-bieten-Nebenjobs-article15144771.html >.