adoption

Adoption (from Latin adoptio ) or adoption instead of a child or adoption as a child describes the legal establishment of a parent-child relationship between the adoptive and the child regardless of biological descent . Both physically related and physically unrelated persons can be adopted; The latter legally take the place of a relative in an adoptive family. The family law relationships between the adopted child and his or her parents of origin generally expire. When adopting adults or close relatives, partially different regulations apply.

Historical

The legal institution of adoption came into the German-speaking area with Roman law (for adoptio see Adoption in the Roman Empire ). The adoptive emperorship represented a special form : It was a period of the Roman Empire, in which the succession in the rule was regularly determined by adoption (98 to 180 AD). It was about the selection of the most suitable candidate as successor. Modern research has put this idealizing view into perspective. In England, where Roman law had very little input, it was still unknown at the end of the 19th century.

In France it was only introduced by Napoleon I through the Civil Code . There, adoption was more restricted because, according to him, only adults can be adopted instead of children, and only if they either saved the life of the adoptive father or were provided with maintenance by him for six years without interruption during their minority .

In Austria , as in Prussia, a judicial confirmation of the adoption contract was required. Thus, the Prussian land law determined that the legal relationships between the adopted and their biological father should not be changed in any way through the adoption, that the adoptive child acquires all the rights of a biological child against the adoptive father, but not vice versa, in that the adoptive father does not Receives claims on the child's property. Furthermore, in Prussia the adoption of a child always had to take place in a written contract and in court, and only people over 50 years of age were allowed to adopt.

In addition to a court contract, the Saxon civil code also required the approval of the sovereign, who, however, was able to exempt from the requirement of 50 years of age on the part of the adopting party and the age difference of at least 18 years. The fathers were allowed to help their illegitimate children not only through legitimation but also through adoption to the rights of legitimate children.

In Germanic tribal law ( Lex Salica ), a child could be adopted through affatomy and at the same time used as an inheritance.

Legal situation in individual countries and legal systems

The following countries sometimes have different regulations:

In the Roman Catholic Church , an adopted child is recognized by canon law if adopted under secular law.

In the Roman Republic , adoptio ("adoption of a child") was a common practice, especially among the upper classes and the senators .

Islamic legal area

In countries that follow the conventional interpretation of Islamic law ( Sharia ), legal adoption according to western standards is not possible (except Indonesia, Malaysia, Somalia, Tunisia and Turkey). This results from the tradition of the Koran, so in sura 33: al-Ahzab (4–5) one speaks of “nominal sons” (translated to “adoptive sons”), whom God “did not make your (real) sons”. Such children are in no way related to their adoptive family. The admission and care of orphans is nevertheless regarded as religiously meritorious and legally regulated under the name " Kafala "; but this does not establish any legal relationship and rather corresponds to a guardianship relationship .

This regulation has led to problems with the recognition of children adopted in Islamic countries when families are relocated to Europe. The European Court of Human Rights confirmed the French authorities against the recognition of an adoption relationship based on a Kafala decision in Algeria .

Supranational regulations and agreements

Hague Convention on International Adoption

The Hague Convention of 29 May 1993 on Protection of Children and Co-operation in Respect of Intercountry Adoption (Convention of 29 May 1993 on Protection of Children and Co-operation in Respect of Intercountry Adoption) aims to ensure the best interests of the child and the Preservation of fundamental rights in international adoptions, in particular the prevention of child trafficking by observing professional standards in international adoptions, cooperation between the contracting states exclusively via central authorities by means of a standardized procedure and ensuring mutual recognition of adoption decisions in all contracting states.

Each state party is required to make efforts to ensure that a child can remain in his or her family of origin. International adoption is only considered as the last step. In any case, there is an administrative or judicial decision on a case-by-case basis, according to the national law of the nation states of the child and parents. In Germany, the Federal Central Agency for International Adoption is responsible.

European Convention on the Adoption of Children

The European Convention on the Adoption of Children of the Council of Europe of April 24, 1967 was signed by 19 states and ratified by 16 states, including the Federal Republic of Germany. A revised version of this convention has so far (status: February 2013) eight member states of the Council of Europe signed and seven states ratified, but not Germany.

Statistics on adoption

In Germany, the number of adoptions fell between 1994 and 2009. In 2008, 2950 children from Germany and 1137 children from abroad were adopted. In 2011 the number of adoptions stabilized. 4060 children were adopted. This is an increase of one percent compared to 2010. In 2012, the number of adoptions fell slightly again. A total of 3886 children were adopted. In the United States, 13,000 foreign children were adopted in 2009. That is more than in all other countries in the world combined.

Transnational Adoption

Adoptions based on the understanding that a child grows up with people who are not the biological parents but who raise the child according to local norms of the parent-child relationship probably existed in all societies at all times. Transnational adoptions, on the other hand, are a relatively new phenomenon in the 20th century. After the end of the Second World War, the Americans felt a responsibility to thousands of war-related orphans in Europe, especially in Germany and Greece, and adopted them under the US Displaced People's Act of 1948 and the Refugee Act of 1953.

The second wave of adoption occurred after the Korean War, which also left many children orphaned. Between 1953 and 1962, around 15,000 children were adopted, mainly from Korea and other Asian countries. There was also the fact that these children - in contrast to the adopted children of the Second World War - outwardly differed greatly from their adoptive parents. Some of the adopted children also emerged from relationships between Korean women and American soldiers.

The primary motivation for an adoption at that time was not one's own childlessness, but a moral responsibility towards the orphans in general and the anger about the treatment of those 'mixed race children' in their countries of origin who were treated there as non-persons. However, this rather philanthropic attitude has changed over the years, so that nowadays transnational adoptions are aimed primarily at childless couples. The countries of origin now also stretch across the globe, with poor countries mostly adopting into the rich. In addition, in many European countries the number of children adopted domestically has fallen drastically in the last few decades, among other things due to the spread of contraceptives and the socially and economically better position of single mothers and the preference for foster care instead of adoption. In addition, the rates of infertility rose, so that many couples were dependent on transnational adoptions.

The numerous actors involved in the process of transnational adoption and the relationships between them range from the private to the macro-political level on a global level. Only some of the relationships are mentioned here, such as those between nation states, between international and national authorities, between the expecting parents and the public authorities that decide on their application and, above all, the relationship between the adoptive child and his adoptive parents or his biological parents.

In addition to the legal hurdles, Howell places particular emphasis on the social processes that are necessary to successfully carry out a transnational adoption. In this context she cites her concept of kinning : “By kinning I mean the process by which a fetus or newborn child is brought into a significant and permanent relationship with a group of people, and the connection is expressed in a conventional kin idiom ". Kinning, she writes, consists of three aspects:

- make related through nature ("kin by nature")

- make related through care ("kin by nurture")

- to make related by the law ("kin by law")

Adoptions in Europe are primarily determined by the latter two.

In the context of adoptions, it is first of all necessary that the person to be adopted is de-kinning . H. that previous family ties have to be broken or nonexistent, as is the case with newborns who are given up for adoption immediately after birth. According to Howell, transnational adoptions are possible because the children who are given up for adoption are “naked” in the social sense: “The child is denuded of all kinship”, a “non-person” left by their previous relatives ( abandoned ). In the further course of the adoption such an autonomous, non-social individual again experiences the process of kinnings , which equips them with a new set of relatives and makes them a related person in the adoptive family.

Barbara Yngvesson also shows the central importance of the dissolution of old kinship relationships: The radical American variant provides for previous kinship relationships to be completely deleted in the case of adoptions and all references to connections to the family of origin to be removed. Through the construction of apparently genealogical relationships to the adoptive family, a natural relationship should arise, at least on paper. For this, the adoptive parents are entered in the child's birth certificate as the birth parents, and the birth mother is virtually deleted.

In some cases, the boundaries between transnational adoptions and local child foster care, which are otherwise differentiated in the literature, are sometimes blurred. In these cases Howell's concept is only applicable in relation to the legal component. For example, if a Ghanaian woman who lives in Europe wants to bring her niece to take care of her in Europe, from her point of view this would be a child foster care. In order to meet the citizenship requirements, she would adopt them. Such transnational adoptions, which from the point of view of those affected actually only allow child care, are becoming more common.

Stepchild adoption

In the stepchild adoption the adopter is a parent of the adoptee married or partnered . What is special about the stepchild adoption is that - unlike other adoptions - the legal descent relationship to the parent married or partnered with the adopting parent is maintained and only the descent relationship to the other biological parent is ended. This makes the child a common child of the spouses or life partners.

In a decision of March 23, 2005 (Az .: XII ZB 10/03) , the Federal Court of Justice set high requirements for stepchild adoptions against the will of a biological parent in Germany . In addition to the general requirements for the substitution of consent for child adoption by the guardianship court , the adoption must offer such a significant advantage for the child that a parent who cared for it would not object. So if the father's rights of access are thwarted by adoption or the stepfather-child relationship is legally secured, this is not sufficient. The Federal Constitutional Court took in a subsequent decision to the Supreme Court ruling in agreement terms.

Unmarried couples

Stepchild adoption has long been a privilege of married couples. The Life Partnership Act opened it to same-sex couples in Germany in 2001 (LPartG § 9 Paragraph 7). However, the Austrian law on registered partnerships passed in 2009 did not make this possible. On February 19, 2013, the European Court of Human Rights reprimanded this ban in Austria. The federal government then announced a new bill that would allow the adoption of stepchildren. The law on the permission to adopt the stepchild was passed in parliament and came into force in Austria on August 1, 2013.

In a decision dated February 8, 2017, the Federal Court of Justice ruled out that the adoption of a stepchild as part of an illegitimate partnership could result in both illegitimate partners becoming parents of the child. On March 26, 2019, however, the Federal Constitutional Court ruled that this general exclusion of unmarried partners from stepchild adoption is unconstitutional. The legislature must adopt a new regulation by March 31, 2020, until then the previous regulations of Section 1754 Paragraphs 1 and 2 BGB and Section 1755 Paragraph 1 Clause 2 and Paragraph 2 BGB may no longer be applied.

On February 13, 2020, stepchild adoption by unmarried couples was made possible by parliament in Germany. The new regulation in Section 1766a of the German Civil Code (BGB) provides that unmarried couples have the option of adopting stepchildren if they have been living together for at least four years or are parents of a joint child with this child in a marriage-like manner.

Adult adoption

Even an adult can be accepted as a child under German law. The prerequisite is that a parent-child relationship has already arisen between the adopting (step-) parent and the adopting (step-) child (Section 1767 (1) BGB ). Adult adoption does not mean that the adoptee has to give up ties to his / her birth parents. In contrast to the adoption of minors, an adult who is of legal age (and his descendants) is basically only related to the adopting parent, but not to his or her family (Section 1770 (1) BGB). The adult adoption thus has only fewer inheritance consequences than the adoption of a child. The children adopted in this way (and their descendants) are thus entitled to inherit twice. They are then the legal heirs of both their birth parents (as the original family) and of the other adopting partner.

The blood relatives of the adults adopted in this way continue to be related to them and are entitled to inherit (Section 1770 (2) BGB). However, this adoption does not result in any relationship or inheritance entitlement between the adopted stepchildren and the other blood-related family of the adopting (step) parent.

Adoption by same-sex couples

Adoption of partner instead of marriage

Before the registered civil partnership was anchored in law , it was not uncommon for one of the partners in a same-sex relationship to adopt the other in order to confirm their mutual affiliation and to create a legal basis, for example with regard to inheritance law. When homosexuality was forbidden or immoral, this was probably done to cover up the true motives for living together. Gustaf Gründgens and Robert T. Odeman are prominent examples of same-sex adults adopting, as is the lesbian granddaughter of IBM founder Watson.

Adoption of a child

By same-sex couples

The question of whether same-sex couples should be allowed to adopt children repeatedly provokes heated discussions.

In Germany , same-sex couples have been able to adopt stepchildren since 2005, so that children can now legally have two parents of the same sex. The joint adoption of children was not legally possible for same-sex couples ( life partners ) until 2017. On the other hand, the Federal Constitutional Court declared the restriction of the possibility for registered civil partners to subsequently adopt a child who had already been adopted by a civil partner by the other civil partner (successive adoption) to be unconstitutional. The Amendment Act of June 20, 2014 implements the decision of the Federal Constitutional Court. Same-sex couples have been able to marry since October 2017 , which means that they can also jointly adopt non-biological children.

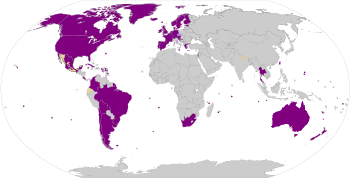

Joint adoption by same-sex couples is now permitted in the following European countries: Andorra , Belgium , Denmark , Germany (from October 1, 2017), Finland , France , Great Britain , Ireland , Iceland , Croatia , Luxembourg , Malta , Netherlands , Norway , Austria (from 2016), Sweden , Spain and Portugal (from 2016). Only one stepchild adoption is allowed in Estonia , Italy , Switzerland and Slovenia .

Outside Europe, joint adoption is permitted in Canada , South Africa , Israel , Argentina , Brazil , New Zealand , Uruguay , the United States (exception: Mississippi ), Colombia , Australia and parts of Mexico .

By individuals

In 2002, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) still rejected adoption by individuals:

"A child should be cared for with a family, not a family with a child."

In January 2008, however, the ECHR ruled that homosexual people should not be denied access to adoption because of their homosexuality. The ruling states that all laws and regulations in the member states of the Council of Europe which refuse to approve an adoption due to the homosexual orientation of the adoptive person violate Article 14 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). Insofar as a member state of the Council of Europe permits adoption by an individual, this must be granted in the member states of the European Council regardless of sexual orientation.

Practices in other countries

In many societies - especially outside of Europe and America - adoptions are negotiated at the local level. For example, they can be associated with a ceremony that symbolizes the reception of a real heir through a sham delivery, suckling the mother's breast or the thumb. It should be noted that the concept of adoption quickly reaches its limits in many cases and can only describe local practices to a limited extent. See the article on foster child .

Adopted personalities

- Steve Jobs (1955–2011), American entrepreneur and co-founder and long-time CEO of Apple

- Marilyn Monroe (1926–1962), American actress

- Bill Clinton (born 1946), 42nd President of the United States

- Philipp Rösler (* 1973), German politician (FDP), former Federal Minister for Health and Economics and Technology

See also

- Foundling (previously abandoned, then found child)

- Orphan (has lost one or both parents)

- Evangelical Association for Adoption and Foster Child Aid (Germany)

- Asociación Nacional de Afectados por las Adopciones Irregulares (children adopted during the Franco dictatorship 1936–1975)

literature

- Angela Aja Aßmuth: Development and Change of Attachment: Psychological Aspects of Adoptions. jmb, Hannover 2016, ISBN 978-3-944342-85-6 .

- Signe Howell: The Kinning of Foreigners: Transnational Adoption in a Global Perspective. Berghahn Books, New York / Oxford 2006 (English).

- Rudolf Leonhard : Adoption 2 . In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume I, 1, Stuttgart 1893, Sp. 398-400 (adoption according to Roman law).

- Gabriele Müller-Engels, Robert Sieghörtner, Nicole Emmerling de Oliveira: Adoption law in practice: including foreign relations. 4th, completely revised edition. Gieseking, Bielefeld 2020, ISBN 978-3-7694-1238-3 .

- Christoph Neukirchen: The legal historical development of adoption . Lang, Frankfurt / M. u. a. 2005, ISBN 3-631-54130-9 .

- Stefanie Sauer: Bicultural adoptive families in Germany: challenges for children, parents and professionals. Budrich, Opladen u. a. 2019, ISBN 978-3-8474-2235-8 .

- Aude Talle: Adoption practices among the pastoral Maasai in East Africa. In: F. Bowie: Cross-cultural Approaches to Adoption. Routledge, London / New York 2004, pp. 64-78 (English).

- Theodor Thalheim : Adoption 1 . In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume I, 1, Stuttgart 1893, Col. 396–398 (adoption in Greece).

- Ulrike Wanitzek: Child Adoption and Foster Care in the Context of legal Pluralism: Case Studies from Ghana. In Erdmute Alber u. a .: Child Fostering in West Africa: New Perspectives on Theory and Practices. Brill, Leiden / Boston 2013, ISBN 978-90-04-25057-4 , pages 221-246 (English; Extract in the Google Book Search).

- Barbara Yngvesson: Belonging in an adopted world: Race, identity, and transnational adoption. University of Chicago Press, Chicago / London 2010, ISBN 978-0-2269-6446-1 (English).

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Muslim Women's Shura Council: Adoption and the Care of Orphan Children: Islam and the Best Interests of the Child. The Digest. Published by the American Society for Muslim Advancement (ASMA), August 2011, pp. ?? (English; PDF: ( Memento of February 10, 2013 in the Internet Archive )).

- ↑ Huda: Islamic Views and Practices Regarding Adoption. In: LearnReligions.com. February 19, 2019, accessed February 26, 2020.

- ↑ Quran text: Sura 33.4. In: Corpus Coranicum . After the translation by Rudi Paret in 1979; Translation: (God) did not make your nominal sons (i.e. adoptive sons) your (real) sons (so that they would have two fathers). That (that is, the formula with the mother's back and the designation of the adopted sons as sons) is just saying that to her (without giving any real facts). "

- ↑ European Court of Human Rights : Case of Harroudj v. France (Application no. 43631/09). Decision on October 4, 2012, final version from April 1, 2013 (English).

- ^ Convention of 29 May 1993 on Protection of Children and Co-operation in Respect of Intercountry Adoption. (English, Hague Conference on Private International Law .net).

- ↑ European Convention on the Adoption of Children: ETS No. 58. April 24, 1967.

- ↑ European Convention on the Adoption of Children (revised): ETS No. 202. November 27, 2008. ( BGBl. 2015 II pp. 2, 3 )

- ↑ Number of adoptions in 2011 almost stable. ( Memento of November 15, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Press release No. 257 of the Federal Statistical Office, July 26, 2012.

- ↑ The number of adoptions in 2012 fell again. ( Memento of June 20, 2018 in the Internet Archive ) Press release No. 250 of the Federal Statistical Office, July 26, 2013.

- ↑ Modern life . In: Focus . No. 11, March 15, 2010, p. 112.

- ^ Howell, Signe 2006. The Kinning of Foreigners. Transnational Adoption in a Global Perspective. New York / Oxford: Berghahn Books. 16

- ^ Howell, Signe 2006. The Kinning of Foreigners. Transnational Adoption in a Global Perspective. New York / Oxford: Berghahn Books. 17th

- ^ Yngvesson, Barbara 2010: Belonging in an adopted world. Race, identity, and transnational adoption. Chicago, London: The University of Chicago Press. 21f.

- ^ Howell, Signe 2006. The Kinning of Foreigners. Transnational Adoption in a Global Perspective. New York / Oxford: Berghahn Books. 18th

- ^ Howell, Signe 2006. The Kinning of Foreigners. Transnational Adoption in a Global Perspective. New York / Oxford: Berghahn Books. XX

- ^ Howell, Signe 2006. The Kinning of Foreigners. Transnational Adoption in a Global Perspective. New York / Oxford: Berghahn Books. 8f.

- ^ Howell, Signe 2006. The Kinning of Foreigners. Transnational Adoption in a Global Perspective. New York / Oxford: Berghahn Books. 4, 8f.

- ^ Yngvesson, Barbara 2010: Belonging in an adopted world. Race, identity, and transnational adoption. Chicago, London: The University of Chicago Press. 22f.

- ^ Wanitzek, Ulrike 2013. Child Adoption and Foster Care in the Context of Legal Pluralism: Case Studies from Ghana. In changing social parenting. Childhood, Kinship and Belonging in West Africa. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer. 221-246.

- ↑ Federal Court of Justice : Order AZ XII ZB 10/03 of March 23, 2005 .

- ↑ Federal Court of Justice: Order AZ XII ZB 10/03 of March 23, 2005 , p. 10: "The [...] of those involved in 2 probably also primarily pursued goal of thwarting the father's right of access by way of adoption, carries how stated, a replacement of the consent usually not. "

- ^ Gregor Völtz: On the requirements and limits of adoption even against the will of the parents. ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) In : rechtstipps.net. May 6, 2006.

- ↑ Federal Constitutional Court : Successful constitutional complaint against the replacement of the biological father's consent in stepchild adoption. Press release No. 123/2005 of December 13, 2005.

- ↑ Life Partnership Act : § 9 legal situation .

- ↑ Philipp Aichinger, Ulrike Weiser: Homosexuals are allowed to adopt children. In: The press . February 19, 2013, accessed January 4, 2014.

- ↑ Parliament Austria: Stepchild adoption is opened for same-sex couples

- ↑ Law Lupe: Not married spouses - and the adoption law; Federal Court of Justice, decision of February 8th, 2017 - XII ZB 586/15. In: right lens. March 7, 2017, accessed May 2, 2019 .

- ↑ Right magnifying glass: Unmarried partners - and the right of adoption: Federal Court of Justice, decision of February 8, 2017 - XII ZB 586/15. In: right lens. March 7, 2017, accessed May 2, 2019 .

-

↑ Anne Hesse in conversation with Nicole Dittmer: Adoption of stepchildren: After four years, unmarried couples are also allowed. In: Deutschlandfunk Kultur . February 13, 2020, accessed on February 14, 2020.

Announcement: Stepchild option possible in future without marriage certificate. In: Zeit.de . February 13, 2020, accessed February 14, 2020. - ↑ Bundestag: Stepchild adoption also for unmarried people. In: Juraexamen.info - online magazine for law studies, state exams and legal clerkship. February 19, 2020, accessed February 25, 2020 .

- ↑ Message: Grotesque family quarrel - lesbian granddaughter fights for IBM inheritance. In: Spiegel Online . February 27, 2007, accessed January 4, 2014.

- ↑ Parvin Sadigh: Homosexuality: The adoption ban for homosexuals is absurd. In: Zeit.de . August 16, 2012, accessed January 4, 2013.

- ↑ Sueddeutsche.de: Ehe für alle, That is changing for homosexual couples

- ^ Federal Constitutional Court, judgment of the First Senate from February 19, 2013 - 1 BvL 1/11 u. a. ( online ).

- ↑ Non- admission of successive adoption by registered life partners is unconstitutional. Press release No. 9/2013 of February 19, 2013. Federal Constitutional Court, Press Office, February 19, 2013, accessed on January 4, 2014 .

- ↑ Act to implement the decision of the Federal Constitutional Court on successive adoption by life partners from June 20, 2014, Federal Law Gazette 2014 Part I No. 27, issued in Bonn on June 26, 2014, p. 786

- ↑ Sueddeutsche.de: Ehe für alle, That is changing for homosexual couples

- ↑ Sueddeutsche.de: Ehe für alle, That is changing for homosexual couples

- ↑ Finland: Finland's parliament votes for gay marriage. (Not available online.) In: Zeit.de . November 28, 2014, archived from the original on October 4, 2017 ; accessed on July 24, 2019 .

- ↑ Thom Senzee: Advocate: Ireland Approves Adoptions by Same-Sex Couples Ahead of Marriage Vote. In: Advocate.com. April 6, 2015, accessed April 7, 2015 .

- ↑ Izvanbračni parovi konačno mogu posvajati djecu ( Croatian ) June 6, 2014. Accessed June 6, 2014.

- ↑ http://www.queer.de/detail.php?article_id=21788

- ^ ORF: VfGH overturns adoption ban for homosexual couples

- ↑ Queer.de: After a change of power, Portugal: Adoption right for gay couples decided

- ↑ repubblica.it:Cassazione, sì alla stepchild adoption in casi particolari

- ↑ Männer.de: Switzerland, stepchild adoption becomes law

- ↑ Queer: Slovenia shrinks from opening up marriage

- ↑ Der Standard: First adoption in a lesbian relationship

- ↑ Mississippi Ban On Adoption By Same-Sex Couples Challenged. The Huffington Post, August 8, 2015, accessed November 6, 2015 .

- ↑ Queer.de : Decision of the Supreme Court, Colombia allows adoption by gay couples , accessed on November 5, 2015.

- ↑ Estella Murgotti: Adoption for same-sex couples now possible throughout Australia. Crew Magazine , March 14, 2018, retrieved on March 22, 2018, quote: "Northern Territory was the last state in Australia to legalize adoption for same-sex couples - adoption for gay and lesbian couples is officially approved throughout the country."

- ↑ Press release from the registry of the European Court of Human Rights. January 22, 2008. (French)

- ↑ Entry: Adoption instead of a child. In: Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon. Volume 1, Leipzig 1905, pp. 544-545 ( online at zeno.org ).

- ↑ e.g. Talle, Aude 2004. Adoption practices among the pastoral Maasai in East Africa. In: F. Bowie. Cross-cultural approaches to adoption. London / New York: Routledge. 64-78.