Roman Republic

The Roman republic ( Latin res publica , literally actually “public matter, public matter”, mostly meaning “community”, applied to modern conditions also “state”) is the constitutional form of the Roman Empire in the period between the end of royal rule (allegedly in 509 BC) and the establishment of the Principate on January 13, 27 BC. Through the relinquishment of power by the Roman Senate, with which the era of the Roman Empire begins. The Roman Republic can best be described as a mixed constitution with aristocratic and certain democratic elements. At the same time, the cultic element played a major role in Roman political life, which influenced the res publica through monarchical institutions .

In a narrower sense, the term “Roman Republic” stands for the history of the Roman Empire in the period mentioned. In ancient Latin usage, however, res publica also generally referred to the Roman state, from the founding of the city of Rome to the end of the imperial era. In addition, Italian communities free from Roman rule were granted to be res publica . For the period of the actual republic , i.e. the form of government between kingship and imperial times, the designation res publica libera ( free state, free state ) was used to make it more precise .

Constitution

A written constitution in the formal sense did not exist in premodern times. The rules of the republic only emerged over the centuries, with five principles of particular importance for the system of government of the Roman republic emerging over time, which were ultimately also laid down:

- All offices (the so-called magistrates ) could only be held for one year ( annuity principle ).

- There had to be an unofficial period of two years between two offices (biennial).

- A second term of office was excluded ( prohibition of iteration ).

- All offices - with the exception of the dictatorship - were occupied by at least two people at the same time ( collegiality ), who controlled each other via the right of intercession : Every holder of an office had the right to prevent or reverse decisions of his colleagues.

- Anyone wishing to exercise an office had to have previously held the next lower office ( cursus honorum ).

The cursus honorum comprised these offices in ascending order:

- Quaestur ( quaestor ): examining magistrate, administration of the state treasury and the state archive (authority potestas )

- Aedility ( aedilis ): police violence, market supervision, festival supervision, temple welfare, organization of games (official authority potestas )

- Praetur ( praetor ): jurisdiction , representation of consuls (authority imperium minus )

- Consulate ( consul ): 2 consuls, responsible for chairing the Senate and Comitia (people's assemblies), jurisdiction, finance, army command. (unrestricted authority imperium maius )

In times of crisis, the consuls and the senate had the option of appointing a dictator for six months . This had the summum imperium , d. H. all offices were subordinate to him, while only the tribunes had a comparable “ sacrosanct ” position.

The officials were elected by a total of three different people's assemblies. Censors , consuls, praetors and the pontifex maximus were elected by the comitia centuriata . The lower offices ( aediles , quaestors and the vigintisex viri ) elected the Comitia tributa . In addition, there was originally the Comitia curiata , but towards the end of the republic it only existed for the sake of form and no longer formed a real popular assembly. Their main function was to formally confirm the ranks of the empire in their office and were involved in adoptions . The concilium plebis finally elected the tribunes and the plebeian aediles .

| Constitutional body: |

state-theoretical classification: |

| Consulate | monarchical element |

| senate | aristocratic element |

| Roman people | democratic element |

The officials were controlled by the Senate and the people's assemblies, which were also responsible for legislation. The members of the Senate were not elected but appointed by the censors . Senators must have held high office and often, but not always, belonged to the nobility . They usually kept their office for life (they could be expelled from the Senate by a censor). Originally the Senate was only reserved for patricians , but after the class struggles were over, plebeians were also able to rise to the senatorial nobility via the cursus honorum . Families that had been consuls were henceforth regarded as particularly important, although the plebeian elite that formed in this way hardly differed from the patrician in reputation in the late phase of the republic. Towards the end of the republic, the Senate was considerably expanded in number to include members of the so-called knighthood, since Sulla had been wearing a quaestur as an entry requirement. All of the high public offices mentioned were, however, unpaid honorary offices ( honores ), which is why only a certain group of people could afford to run and exercise.

As an approximation, one can speak of an intertwining of powers in which neither the executive and judiciary nor the civil and military branches were separated. Due to the numerous state offices in which many fundamentally different elements of ancient state thought can be found, even contemporaries found the theoretical classification of the Roman republic difficult: It was neither a pure aristocracy, nor a democracy or even a monarchy . The ancient historiographer Polybius first characterized republican Rome as a so-called mixed constitution , which combines various elements of well-known pure constitutional forms ( monarchy - consulate, aristocracy - senate and democracy - popular assembly) and is therefore particularly durable.

History of the republic

Origin of the republic

An exact date for the emergence of the Roman Republic cannot be given, as the early sources date from a much later period. Even in modern research, there is by no means agreement on many points.

The Roman historian Titus Livius reports about the birth of Christ in 509 BC. The last Roman king, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, was expelled and Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus and Lucius Junius Brutus were elected as the first consuls (see: List of Roman Consuls ). In addition to the new freedom, he names the most important achievements, namely that from then on the rule of laws was more decisive than that of people, the principles of annuity and the collegiality of the magistrates. However, the republic was probably only established around 475 BC at the earliest. And only attained its “classical” form in the course of the following two hundred years. In retrospect, the rule of kings was viewed by many Romans as tyranny and accordingly rejected; However, this aversion may have been less pronounced in the broader population than in the politically active upper class.

In the 5th century BC For the Roman city-state , the main focus was obviously on the conflict with the Etruscans . Around the middle of the 5th century, the law applicable to Roman citizens was recorded on twelve tablets ; the example of the Greeks was followed.

Rome probably had as early as the 6th century BC. Played an important role in the Lazio landscape ( how important this was is also controversial). After the establishment of the republic, an expansion policy began, which initially mostly resulted from the military defense against an alleged external threat. According to later tradition, the decisive turning point from defense to expansion was the sacking of the city on dies ater 387 BC. BC, which was transfigured as a black day to a warning. From now on, at the latest, the goal was no longer just defense, but also the ultimate victory over the attackers and their submission. The Romans, however, always regarded negotiated peace as only temporary.

In peace negotiations with subjugated enemies, however, the Romans usually proved to be flexible and usually concluded alliances ( foedera ) with the opponents they had just defeated on acceptable terms. The foederati or socii (allies) from then on had to pay taxes and fight for Rome, but received a share of the movable booty. The upper class of the allied communities could easily acquire Roman citizenship; however, a defection from Rome was mercilessly punished. In this way, through the newly won allies among the Italian tribes in central Italy, Roman power grew continuously. The subject was barred from making alliances with one another, so that the empire - according to the principle of divide et impera ! - was a system of bilateral treaties centered on Rome.

However, the recognized weakness of a city or an area was also exploited to conquer it and incorporate it into Roman territory, as was the case with the Etruscan city of Veji in 396 BC. In the process, the defeated opponents were treated far more ruthlessly, the population was enslaved and their property was distributed among the Roman citizens.

After a good hundred years of expansion, the small republic suffered in 387 BC. A severe setback when Rome was captured and sacked by the Gallic Senones . As mentioned, this experience immediately affected the policy of the young republic. As a result, Rome armed and soon expanded south and north. The Samnites were able to fight hard and protracted battles (again understood as defensive battles) between 343 and 290 BC. And their territory was incorporated into Roman territory in the so-called Samnite Wars . The Etruscans, on the other hand, who previously dominated the area north of Rome and whose power was in decline, were subjected to Roman power in barely concealed wars of aggression.

In Rome, the plebeians fought for more and more rights and also access to the various offices in the course of the class struggles . It is significant that these offices offered the respective persons the opportunity to gain respect, but at the same time they were required to steer personal ambitions in ways that were also useful to the community. The “hunger for reputation” of many Romans can be regarded as a characteristic of the Roman Republic, which should prove to be a heavy burden, especially in the time of crisis in the Republic. At the end of the conflict, a new republican aristocracy, the nobility, emerged .

Rise to the supremacy of Italy

In the period after 340 BC The Romans succeeded in bringing most of the cities in the Lazio region under Roman control during the Latin Wars . From around 280 BC. The Romans also subjugated southern Italy, where the Greeks had settled centuries earlier (see also the Tarentine War , connected with the battles against the Epirotian king Pyrrhus ). To secure their rule, the Romans created several colonies. Furthermore, Rome established an alliance system with several cities and tribes, including the Samnites, who had been subjected to hard battles (see above).

So there was

- full Roman citizens (from the city of Rome, the colonies or incorporated tribes),

- Municipalities with Roman citizenship but without voting rights , and

- Allies who were able to retain their internal autonomy.

This alliance system became the cornerstone of what is now called the Roman Empire.

In the period between 264 BC BC and 146 BC BC Rome waged the three Punic Wars , through which the city-state finally rose to become a great power. The First Punic War (264–241 BC) arose due to Rome's expansionist policy towards the commercial republic of Carthage . Rome was forced to build a fleet. 241 BC It destroyed the Carthaginian fleet near the Egadi Islands . Carthage paid war indemnities and renounced Sicily, but retained its sphere of influence in Hispania , where the Barkids established a new Carthaginian colonial empire.

Meanwhile, Rome established in its conquests the provinces of Sicilia (241 BC) and Sardinia et Corsica (238 BC), the administration of which was entrusted to former praetors.

The Illyrian Wars , during which the republic acquired its first possessions on the eastern Adriatic coast, began in 229 BC. BC Rome's engagement in the east. A little later, the subjugation of the Gauls began in the Po Valley.

Practical test against Hannibal

The Carthaginian strategist Hannibal came from Spain in 218 BC. In the Second Punic War (218–201 BC) against Rome. He crossed the Alps and carried the war into the Roman heartland. After several defeats by the Romans (including the Battle of Lake Trasimeno in 217 BC) it seemed as if Rome would fall. In the greatest need, the Roman state intervened in 217 BC. To the ultimate means, the appointment of a dictator . Since the dictator Quintus Fabius Maximus Cunctator used a slow defensive strategy, Hannibal was not able to break the Roman will to resist despite all his successes (especially in the battle of Cannae in 216 BC ). In particular, he did not succeed in breaking the Italian system of alliances in Rome. After an alliance between Hannibal and Philip V of Macedonia remained ineffective, u. a. the general Marcus Claudius Marcellus gradually put the Carthaginians on the defensive in Italy. Fabius Maximus and Marcellus were therefore also referred to by Poseidonios as "the shield and sword of Rome". During the attack on the Barcidian possessions in Hispania, Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus succeeded in defeating the Carthaginians until 206 BC. From the Iberian Peninsula. 204 BC He landed in North Africa and defeated Hannibal there in 202 BC. At Zama decisive. In the peace agreement, Carthage lost all external possessions and the fleet.

The averting of the deadly threat to their state by the genius general Carthage became a second founding myth of the city for the Romans of the following generations, a constant source of inspiration in seemingly hopeless situations and a shining ideal of civil virtue.

The price of world power

With the establishment of the provinces Gallia cisalpina (203 BC) and Hispania citerior and Hispania ulterior (197 BC) the number of administrative areas outside of Italy rose to five, 168 BC. A sixth was added with the province of Illyricum .

As early as 200 BC Rome had intervened in Greece against the hegemony of Macedonia under the Antigonid Philip V and defeated him in the Second Macedonian-Roman War . 196 BC Greece was declared free by the philhellenic minded Titus Quinctius Flamininus . Nevertheless, as a protectorate power, Rome determined the fate of the Hellenes from now on. It fought in the Roman-Syrian War in 192–190 BC. Against the Seleucid king Antiochus III. who lost the decisive battle at Magnesia . After the Seleucids were displaced from Asia Minor to the Taurus, the empire of Pergamon was installed there as a new regulatory factor. At this point in time Rome was definitely the supreme power in the Mediterranean, and in the following decades the “irritable world power” abandoned all restraint. Rome now dictated the conditions, and in the conflict between the Seleucid king Antiochus IV, who had invaded Egypt, and the Ptolemaic Empire , on the day of Eleusis in 168 BC it was enough . An ultimate word from the Roman envoy Gaius Popillius Laenas to move the victorious Seleucids to surrender all conquests. Antiochus was warned by the fate of the Antigonids, whose last king Perseus was disempowered, captured and imprisoned for the rest of his life after the battle of Pydna barely a month before.

After the elimination of Macedonia and the destruction of Corinth (146 BC), all of Greece was finally absorbed into the province of Macedonia . In the same year, after the Third Punic War (149–146 BC), Carthage was also destroyed and the province of Africa established. 133 BC As a result of a treaty of inheritance on the soil of the empire of Pergamon, the province of Asia followed , whereby the total number of provinces rose to nine.

The rise of Rome to a great power brought a number of problems for the state in addition to many advantages. The administration of the provinces in particular became a challenge with serious side effects. The possibility of exploitation of the subjects was a great temptation for many promagistrates, so that there was a dangerous increase in corruption. It soon became common for candidates for the most important state offices to get into debt during the election campaign in the sure expectation that the provincial administration would later return the expenses with good interest. The victims of this policy sometimes tried to defend themselves with so-called repetition proceedings against the most brazen tormentors, but as a result these often spectacular trials only stirred up greater unrest in the Roman nobility.

By conquering large parts of the Mediterranean region, Roman society was increasingly exposed to foreign cultural influences. Above all, the close contact with the Hellenistic world left deep traces. Especially in the Roman upper class, the refined customs of the Greeks became the predominant fashion until even the luxury of the Orient was no longer frowned upon. A popular saying of the time therefore claimed that Greece, after being conquered by Rome, conquered the Romans themselves.

As an ancient Roman-conservative representative against "foreign infiltration and moral decay" due to Greek influences occurred in the first half of the 2nd century BC. BC the censor Marcus Porcius Cato the Elder , who admonished his younger Senate colleagues in speeches and writings not to lose sight of the decency and virtue of their ancestors. His censorship in 184 BC Chr. Was especially sensational because as a homo novus (political climber) he attacked even the most distinguished nobiles with relentless energy and without the usual consideration due to his authority and rhetorical skills. However, even he was unable to suppress the Hellenistic influence on the customs of Roman society in the long term.

The crisis of the republic

Under the influence of these changes, the foundations of the Roman Republic finally showed the first cracks: the stubborn resistance of the Celtiberians in the Spanish War (154-133 BC) showed the legions their limits for the first time since the days of Hannibal. 136 BC The slave war began in Sicily. From 133 BC During the phase of the “Roman Revolution” ( Ronald Syme ), the republic experienced a serious and lasting crisis.

The agrarian question and the closely related question of the military constitution turned out to be decisive catalysts. The traditional militia system , in which all citizens of the city were involved in defense and warfare and paid for their own military equipment, turned out to be no longer practicable in view of the many campaigns made necessary by the expansion. On the one hand, many small farmers became impoverished because they were less and less able to carry out their agricultural activities due to the extensive campaigns and more economically lost due to the wars they won. On the other hand, few patrician landowners were able to use their war booty to acquire large estates, so-called latifundia , with the products of which they also put the common peasants at competitive prices. The contrasts eventually led to a century of civil wars that ended with the fall of the republic.

The attempts at reform by the Gracches

The tribune Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus struck around 133 BC. BC introduced a land reform in order to distribute the large estates beyond a fixed amount to dispossessed proletarians , and thus to strengthen the small farmers again. The agrarian reform thus also had the declared aim of counteracting the alleged weakening of Roman military strength. Tiberius himself came from a wealthy family and was supported by important senators; the question of why his proposals met the bitter resistance of many other senators is controversial in research. Although his proposal did not find a majority in the Senate, he nevertheless introduced it to the popular assembly; a first break with republican norms. When the opponents of the reform then sent the tribune Marcus Octavius to prevent the reform by veto , Gracchus had his competitor removed by voting in the popular assembly . This breach of the constitution and the equally unlawful candidacy for a second term of office led several senators to slay the uncomfortable politician during a popular assembly because he was accused of wanting to establish a tyranny .

Ten years after these events, the tribune Gaius Sempronius Gracchus had more far-reaching goals ( Leges Semproniae ). In memory of his murdered brother, he began with the renewal of the arable law and with a measure to supply the needy urban population with cheap grain. Further proposals were aimed at filling the judges' positions with members from the equestrian order , taxing the province of Asia and granting Roman citizenship to the Italian allies . In particular, the proposed law to expand civil rights brought him into political sideline. Even the knighthood refused to support him despite the newly granted rights. Fearing a constitutional overthrow, the Senate majority finally took action against Gracchus and his supporters, who holed up on the Aventine under the leadership of the former consul Marcus Fulvius Flaccus . The Senate then declared a state of emergency ( SCU = Senatus consultum ultimum ) for the first time and had the rioters killed in bloody street fights.

Optimates and Populars

From then on, the conflicts within the Roman upper class escalated more and more. At least since the death of the Gracchi, the two groups of optimates and populars had been increasingly irreconcilable in Rome . Both consisted of members of the nobility , and neither were they parties in the modern sense. While the so-called Optimates endeavored to preserve the overwhelming influence of the Senate, the Populares, often particularly powerful aristocrats, sought to exploit the social contradictions politically by promising reforms in order to prevail against their rivals in this way and bypassing the Senate. At least since the Gracchi, they preferred to use the legislative people's assembly. An important step in the career of a popular politician, therefore, was the sacrosanct office of the People's Tribune, which was used by ambitious applicants to propose land reforms or grain distributions in order to gain popularity. Their opponents in the same office, however, could use their veto power to prevent the reforms.

One of the first politicians to emulate the model of the Gracchi was the tribune Lucius Appuleius Saturninus , who lived in 100 BC. Was declared an enemy of the state and was also slain. After this previous burden, the people's tribunate remained a problematic element of the Roman constitution, as it could on the one hand be used to advance important reforms, but on the other hand always smelled of the constitutional overthrow. The first breaches of the law at the time of the Gracchi soon resulted in more, which would eventually lead to the decline of the republic.

The army reform of Marius

When the invasion of the Cimbri and Teutons (113-101 BC) in the Alps and the Jugurthin War (111-105 BC) in Numidia showed the limits of Roman military power, the Roman general and later leader of the Populares Gaius Marius finally carried out a comprehensive reform of the traditional military constitution. By introducing a professional army of paid, well-trained and long-serving soldiers, whom he had just recruited from the newly created, dispossessed Roman lower class and who could hope for special privileges after their service time, he was in a position to militarily prevent the loss of the traditional militia army more than compensate.

However, at a time when the military power of a society was very important, the restructuring of the army constitution led to completely new, unforeseen social changes: The new military constitution led to the so-called army clientele , the closer ties between soldiers and their respective general. For the mostly possessed soldiers, military service was no longer a duty alongside their normal job, but the only way to earn a living. The mercenaries therefore expected booty from their generals and, moreover, a supply of land after their release. The care of the veterans now became an issue that repeatedly influenced the political discussion in Rome.

The first general whose career made these new dependencies clear was Marius, who after his army reform destroyed the Cimbri and Teutons and then rose to become the leader of the Populares by caring for his veterans and the associated land problems, of whom he was elected consul seven times .

The close ties between the troops and individual generals turned out to be a heavy burden on the political constitution in another respect as well. For the generals now had the opportunity to enforce their own interests with the troops surrendered to them, even against the will of the Senate or the People's Assembly. The age of civil wars is shaped by these “private” armies of ambitious politicians. A structural problem arose: The sons of the Roman nobility were expected to have a successful career in the military and civil service, but afterwards they were supposed to join the hierarchy again.

Sulla's dictatorship

91-89 BC It came to the alliance war in the course of which the Roman allies finally fought for full citizenship. 88 BC The fight against Mithridates VI began. of Pontus , who had several thousand Roman settlers killed in one night ( Vespers of Ephesus ).

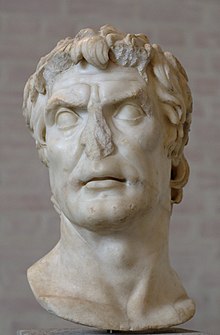

In Roman domestic politics, there was an escalation of violence between the parties of the Optimates and Populares, in the course of which the leader of the Optimates Lucius Cornelius Sulla and then the Populares under Gaius Marius and Lucius Cornelius Cinna at the head of their armed supporters the capital marched to put their opponents in their place and to seize sole power. After Sulla had succeeded in pushing Mithridates back in the east, he returned to Italy with his veterans and marched a second time on Rome to end the rule of the Populares, whose leaders Marius and Cinna had died. Then he was appointed dictator for the purpose of reorganizing the state (82-79 BC) and established a short-term reign of terror in the course of which numerous opponents were placed on proscription lists in order to declare them outlawed and to be able to murder them with impunity. Through constitutional reforms, including the limitation of the powers of the tribunes by limiting the right of veto, he then looked for ways to re-establish the rule of the Senate. He increased the number of members in the Senate from 300 to 600. He also reorganized the magistrate by weakening the highest office holders and imposing minimum age regulations and restrictions on re-election. When he believed he had done enough, he voluntarily resigned his dictatorship and withdrew from politics.

The illusion of the “Sulla Restoration” did not last long, however. After his early death in 78 BC His actions, and especially the crimes of his followers, became a source of ongoing conflict. The relatives of the victims, who had often also lost their property, demanded rehabilitation and compensation, but only gradually were able to make their voices heard in legal proceedings. Many of the dictator's measures were reversed in the following decades, and the tribunes were also revoked after a certain period in 70 BC. Chr. Reinstated in their full rights.

The first triumvirate

As a result of the crisis of the late republic, the successful generals were of particular importance. Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus , who had served under Sulla at a young age, fought 76–71 BC. Ultimately successful against the party of the Marian Quintus Sertorius in Spain and after his return to Italy defeated the remains of the troops of Spartacus , whose slave revolt (73–71 BC) had been suppressed by Marcus Licinius Crassus . In the following year 70 BC Pompey and Crassus held the consulate together. During this time, although they were among the supporters of Sulla, they revised some unpopular decisions such as the curtailment of the powers of the tribunes. Pompey then achieved great fame through the elimination of the Cilician pirates (67 BC), through the final conquest of Mithridates and the reorganization of the Near East (64/63 BC), where he a. a. eliminated the Seleucid Empire and established the province of Syria in its place , and also protected the Roman rule there through several upstream client states. The extraordinary empires required for his tasks gave Pompey a power that no Roman general had possessed before him. For this reason, resistance against the successful generals formed among the Optimates, as they saw their influence threatened.

After the return of Pompey from the east in 62 BC. However, the old problem of caring for his soldiers who had been voluntarily retired was presented again. Since, despite his enormous reputation, the general was unable to assert himself politically against the conservative forces in the Senate, which had been strengthened after the suppression of the Catiline conspiracy (63 BC), he looked for alternative paths. His secret alliance with Marcus Licinius Crassus and Gaius Iulius Caesar (60 BC) was then a clear attempt to circumvent the constitutional distribution of power. The so-called First Triumvirate is a clear indication of the structural weakness of the late republic, whose institutions did not show themselves to be able to cope with the new requirements. In fact, there was no longer any free choice of consuls and the drawing of the provinces afterwards, because the triumvirs distributed all important state offices in advance among their followers and, by bribing or intimidating the opposing party, ensured that the comitia voted in their favor. Attentive observers such as the important speaker Marcus Tullius Cicero recognized the crisis, but could not prevail against the more radical forces on both sides, among which the shady tribune Publius Clodius Pulcher for the popular and the morally strict praetor Marcus Porcius Cato the Younger for the Optimates Sound specified. "Cato makes motions as if he were in Plato's ideal state and not in Romulus' pigsty," said Cicero of the all too righteous colleague and the contradictions of his time.

As consul, Caesar continued in 59 BC. By ignoring his official colleague, the recognition of Pompey's orders in the east as well as his veterans benefiting agricultural laws through. For himself, Caesar achieved the transfer of a five-year governorship over two Gallic provinces, which was later extended for another five years. In this position he subjugated 58–51 BC. In bloody battles the until then free Gaul up to the Rhine and thereby outstripped Pompey. After the death of Crassus after his defeat by the Parthians at Carrhae (53 BC), the competition between the two remaining triumvirs increased steadily. The death of Juliet , Caesar's daughter and wife of Pompey, and Pompey's rapprochement with the conservative Senate circles, who feared for their republican freedom, also contributed to this.

Civil war and Caesar's sole rule

With the support of the Optimates, Pompey received Hispania to counterbalance Caesar's province of Gaul. Caesar's greatest problem, however, was the threat of his opponents to bring him to court as a private citizen after his return to Rome. He therefore sought special permission to apply in absentia for a new state office before his mandate expired, which would have extended his immunity. Trusting in the power of Pompey, the senators rejected the request. In anticipation of a negative answer, Caesar had already prepared for the civil war and raised additional troops in his province. After his last compromise proposal had been rejected by the supporters of Pompey, he exceeded in the beginning of 49 BC. The Rubicon , the border between its province and Italy. The consuls and the senate had him declared an enemy of the state by declaring a state of emergency ( Senatus consultum ultimum ), but were forced by his advance to evacuate the capital and, under the leadership of Pompey, fled across the Adriatic to Epirus . In the civil war that followed, Pompey was defeated in 48 BC. Defeated by Caesar near Pharsalus in Thessaly and murdered soon after in Egypt.

After a warlike interlude in support of Cleopatra in Egypt, Caesar led further battles against the Pompeians, which he decisively defeated at Thapsus in North Africa (Catos suicide in 46 BC) and at Munda in Spain (45 BC). After that he was de facto sole ruler of the Roman Empire and filled the state offices at will. For him, the republican form of government, which for him was “nothing, a mere name without body and shape”, no longer had a future. Despite his policy of reconciliation, a conspiracy under the leadership of Marcus Iunius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus , the Caesar on March 15, 44 BC , arose against the increasingly dictatorial ruler . BC ( Ides of March ) fell victim.

The conspirators hoped that the assassination of the "tyrant" would restore a republic ruled by the Senate aristocracy. In this sense, the consular Cicero, who was not informed about the planning of the attack, welcomed this act. In a series of speeches he fought Caesar's close confidante and consul Marcus Antonius , as he assumed that he had similar attempts at power as the murdered man.

Second triumvirate and end of the republic

Cicero succeeded in integrating Caesar's great-nephew and main heir Octavian (later Emperor Augustus) into a military coalition that Mark Antony established in April 43 BC. In the Mutinensian War . When the Senate then dropped Octavian, he concluded with his former opponent Antonius and with Marcus Aemilius Lepidus at the beginning of November 43 BC. The Second Triumvirate , whose rule they ushered in with the publication of extensive proscription lists, on which they declared high-ranking opponents and supporters of the republic to be outlawed. One of the most prominent victims in the wave of murders that followed was Cicero. The triumvirs finally struck in October / November 42 BC. The armies of Brutus and Cassius in the battle of Philippi in Macedonia and thus sealed the fall of the republic.

While Mark Antony organized the eastern provinces, Octavian was supposed to distribute land to the veterans in Italy. He came into conflict with Antonius 'wife Fulvia and Antonius' brother Lucius and defeated them in 41 BC. In the Peruvian War . In the autumn of 40 BC The Treaty of Brundisium came about, in which the spheres of interest between the triumvirs were divided in such a way that Octavian received the west and Mark Antony the east of the Roman Empire as a sphere of power. Despite Antonius' marriage to Octavian's sister Octavia , tensions remained.

The contract of Misenum with Sextus Pompeius , who had taken in the persecuted and refugees in Sicily, succeeded in 39 BC. The rehabilitation of the proscribed (with the exception of the Caesar murderers ), whereby a long-term legal uncertainty like after Sulla's proscriptions could be avoided. After the victory over Sextus and the disempowerment of Lepidus, Octavian was 36 BC. Undisputed ruler in the west. In the same year, however, Mark Antony suffered a defeat against the Parthians. 34 BC He raised his lover Cleopatra to queen of kings .

Decision-making battle and justification of the principle

When the outbreak of the final battle between the two remaining triumvirs became apparent, Octavian instrumentalized in 32 BC. The relationship between Marcus Antonius and the Egyptian queen was established in the 3rd century BC in order to propagandistically portray the looming civil war as an alleged war against an enemy from abroad: He had Cleopatra, who posed a threat to Italy, and not the allegedly impotent Antonius declare war . 31 BC The decisive conflict took place in Greece, during which Octavian was able to defeat Antonius in the sea battle of Actium . In a hopeless situation, Antony and Cleopatra committed suicide in Egypt the next year. The Nile land was directly subordinate to the new Roman ruler Octavian as a province .

After he had defeated all opponents, Octavian staged the transfer of the republican authority to his person and thus founded the principate (27 BC). He received the honorary name Augustus and thus became the progenitor of the Roman Empire . The illusion of a republican form of government persisted, and Augustus and his successors ruled formally on the basis of exceptional powers, but from now on power lay in the hands of the princeps , the first among equals, who was in truth an absolute ruler.

For a long time, however, the rulers believed themselves to be dependent on the cooperation of the nobility . Outwardly, the res publica , embodied by the Senate and the offices of the cursus honorum , remained in existence for centuries after Augustus. It was not until the 6th century, at the end of late antiquity , that the consulate was effectively abolished in 542, and around 590 the (“ Western Roman ”) Senate also disappeared.

literature

- Heinz Bellen : From the royal period to the transition from the republic to the principate (= basic features of Roman history. Vol. 1). 2nd revised edition. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1995, ISBN 3-534-02726-4 .

- Jochen Bleicken : History of the Roman Republic (= Oldenbourg floor plan of history . Vol. 2). 6th edition. Oldenbourg, Munich 2004. ISBN 978-3-486-49666-6 . Concise presentation with research section and extensive bibliography.

- Jochen Bleicken: The Constitution of the Roman Republic. Basics and development (= UTB. Vol. 460). 8th edition, unchanged reprint of the completely revised and expanded 7th edition. Schöningh, Paderborn 2008, ISBN 978-3-506-99405-9 . Standard work.

- Wolfgang Blösel : The Roman Republic. Forum and expansion. CH Beck, Munich 2015, ISBN 978-3-406-67413-6 .

- Klaus Bringmann : History of the Roman Republic: From the Beginnings to Augustus. (= Series of publications: Beck's Historische Bibliothek ), 3rd expanded edition, Verlag CH Beck, 2017, ISBN 978-3-406-71466-5 . Solid and fluent presentation.

- Thomas Robert Shannon Broughton : Magistrates of the Roman Republic. Vol. 1: 509 BC-100 BC Vol. 2: 99 BC-31 BC Vol. 3: Supplements (= Philological monographs of the American Philological Association. Vol. 15). American Philological Association, New York 1951-1960. (Reprinted: Scholars Press, Atlanta 1984–1986, ISBN 0-89130-812-1 )

- Karl Christ : Crisis and Fall of the Roman Republic. 6th edition, unchanged reprint of the 5th edition. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2008, ISBN 978-3-534-20041-2 . Detailed study with numerous other references on the crisis of the republic.

- Tim J. Cornell: The Beginnings of Rome. Italy and Rome from the Bronze Age to the Punic Wars (c. 1000-264 BC). Routledge, London - New York 1995, ISBN 0-415-01596-0 , ( Routledge history of the ancient world ) (Reprinted 1997, 2006, 2007). Important presentation regarding early Roman history.

- Harriet I. Flower (Ed.): The Cambridge Companion to the Roman Republic. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge et al. 2004, ISBN 978-0-521-80794-4 (2007 reprinted).

- Gary Forsythe: A Critical History of Early Rome. From Prehistory to the First Punic War. University of California Press, Berkeley 2005, ISBN 0-520-22651-8 .

- Erich S. Gruen : The last generation of the Roman Republic. University of California Press, Berkeley 1974, (Reprinted 1974, 1995, 2007 ISBN 978-0-520-20153-8 ).

- Herbert Heftner : The Rise of Rome. From the Pyrrhic War to the fall of Carthage (280–146 BC). 2nd improved edition. Pustet, Regensburg 2005, ISBN 3-7917-1563-1 .

- Herbert Heftner: From the Gracchen to Sulla. The Roman Republic at the crossroads (133–78 BC). Pustet, Regensburg 2006, ISBN 978-3-7917-2003-6 .

- Martin Jehne : The Roman Republic. From the foundation to Caesar (= Beck'sche series. Knowledge. Vol. 2362). 2nd Edition. Beck, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-0-349-11563-4 . Brief introduction.

- Andrew Lintott: The Constitution of the Roman Republic. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1999, ISBN 978-0-199-26108-6 .

- Nathan Rosenstein, Robert Morstein-Marx (Eds.): A Companion to the Roman Republic. Blackwell, Oxford 2006, ISBN 978-1-4051-0217-9 , (Reprinted 2007, 2008). Compact essays on the current state of research, English, German, French and Italian research are equally taken into account.

- Michael Sommer : Rome and the ancient world until the end of the republic (= Kröner's pocket edition. Vol. 449). Kröner, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-520-44901-6 .

- Uwe Walter : Memoria and res publica. On the culture of history in republican Rome (= studies on ancient history. Vol. 1). Antike, Frankfurt am Main 2004, ISBN 3-938032-00-6 (also: Cologne, Univ., Habil.-Schr., 2002).

- Uwe Walter: Political Order in the Roman Republic (= Encyclopedia of Greco-Roman Antiquity . Volume 6), ed. by Aloys Winterling , De Gruyter Oldenbourg, Berlin, Boston 2017, ISBN 978-3-486-59696-0 .

Remarks

- ^ Titus Livius, Ab urbe condita 1.60

- ↑ Livy 2,1

- ↑ "imperia legum potentiora quam hominum" (Livius, 2,1,1)

- ↑ Poseidonios in Plutarch , Fabius 19, 5 and Marcellus 9, 3.

- ^ Klaus Bringmann: History of the Roman Republic. Munich 2002, p. 134ff.

- ^ A b Pedro Barceló: Brief Roman History. 2nd, bibliographically updated edition, Darmstadt 2012, p. 46.

- ^ Pedro Barceló: Short Roman History. 2nd edition, Darmstadt 2012, p. 49.

- ^ Pedro Barceló: Short Roman History. 2nd, bibliographically updated edition, Darmstadt 2012, p. 52.

- ^ Pedro Barceló: Short Roman History. 2nd, bibliographically updated edition, Darmstadt 2012, p. 54.

- ^ Cicero, Ad Atticum 2, 1, 8.

- ^ Pedro Barceló: Short Roman History. 2nd, bibliographically updated edition, Darmstadt 2012, p. 58 f.

- ↑ Suetonius , Caesar 77, 1 .