Antiochus III.

Antiochus III. (* 242 BC ; † June / July 187 BC at Susa ), known as Antiochus the Great , was king of the Seleucid Empire (223–187 BC) and one of the most important Hellenistic rulers. He was a son of Seleukos II and younger brother of Seleukos III. , which he succeeded. Antiochus' nickname "the great" corresponds to the title Megas Basileus (great king), the traditional name of the Persian Achaemenids , which he assumed .

Life

Consolidation of the Empire (223-213)

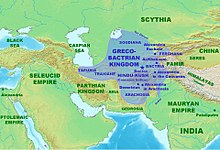

When Antiochus ascended the throne at the age of about eighteen, the Seleucid Empire was in a continuous phase of dissolution, which had lasted since the death of Seleucus I , the founder of the dynasty . Numerous provinces (or satrapies ) that were on the periphery of the empire, such as Parthia , Bactria , Atropatene or Armenia , had already gradually fallen away without the Seleucid rulers being able to do anything about it. A rebellion in their second most important province Mesopotamia at the beginning of Antiochus' rule now threatened the continued existence of the Seleucids as a great power. Two military expeditions under Seleucid generals failed because of the leadership of Molon , the leader of the uprising. It was not until Antiochus in 221 BC. Chr. Personally led a force against the separatists, the uprising collapsed.

A cousin of the king, Achaios , had been able to recapture the western interior of the peninsula from the Attalids in his function as viceroy of Asia Minor since 223 . In 220 he finally had his soldiers proclaim him king. His otherwise loyal followers, however, refused to undertake a campaign to Syria against their former king Antiochus. This let his renegade relatives rule for the time being, because he wanted to undertake a campaign against Ptolemaic Egypt that had been planned for a long time . The two Hellenistic monarchies had been fighting over the possession of the rich provinces of Koilesyria and Phenicia for decades . From 219 to 217, Syria and Egypt therefore waged the Fourth Syrian War . Antiochus was able to record several successes and took, among other things, the important port of Seleukia Pieria in Syria. In the decisive battle at Raphia , however, he suffered in 217 BC. A defeat that destroyed all of his previous successes except for the possession of Seleukias.

Antiochus now turned against his cousin Achaios. For this he allied himself with the otherwise anti-Seleucid kings of Pergamon , who saw themselves threatened by Achaios. Ultimately, Antiochus limited his relative to the capital of Sardis . After a year of siege, the city gave in 213 BC. BC on their resistance, whereupon Achaios was executed. Antiochus had brought the centrifugal forces in the Seleucid Empire to a standstill. Atropatene had already recognized the Seleucid supremacy again in 220. When Antiochus' empire only consisted of the central areas of Syria and Mesopotamia at the beginning of his rule, he had now expanded this to most of Asia Minor and consolidated the borders in the north and south.

Anabasis (212-205)

In the next few years Antiochus continued with an extensive campaign against the lost fringes of the Seleucid Empire . This is the so-called anabasis (212–205 / 4 BC). The campaign began with the submission of Armenia . 209 BC He undertook an invasion of the Parthian Empire and conquered its capital, Hekatompylos . The Parthian king then reached a peace treaty. In the same year Antiochus led his army against Bactria and also besieged its capital Baktra (today Balch ). After the peace agreement with Bactria's King Euthydemos I (206 BC) he moved to India following the example of Seleucus and there concluded a treaty with the Maurya (?) King Saubhagasena.

These campaigns left a lasting impression on the Greek world. The anabasis of Antiochus was used very successfully for propaganda purposes in Greece. However, it was of little value in terms of realpolitik: The formally subjugated local kings of Parthia, Bactria and India were to control the empire after the death of Antiochus III. leave again.

Struggle for supremacy in the Eastern Mediterranean (204–196)

As of 204 BC When a child ascended the throne of Egypt with Ptolemy V , Antiochus forged new plans to conquer Palestine. He undertook a new attack and won 198 BC. BC a decisive victory at Paneas at the sources of the Jordan , which ended the rule of the Ptolemies over Palestine ( see: Fifth Syrian War ).

The "Cold War" with Rome (196–192)

In Asia Minor, the Seleucids only controlled the inland areas in the west of the peninsula. The coastal areas were under the control of Egypt, Pergamon and Rhodes . Philip V of Macedonia had also tried to gain a foothold in Caria and Ionia since the robbery treaty , but his position in Asia Minor collapsed during the Second Macedonian War against Rome. Antiochus therefore moved to Asia Minor one more time after his victory in the Fifth Syrian War in order to secure the former territories of the Ptolemies and Antigonids. He got by for the most part without military operations, since he made alliances with the Greek cities located there and left them their autonomy. Exceptions were, however, Smyrna and Lampsakus , who asked Rome for help against Antiochus. The Seleucid king initially avoided the two cities and crossed over to Europe. In Thrace he rebuilt the almost completely abandoned city of Lysimacheia , which had been overrun by the local tribes.

The Romans initially feared that Antiochus wanted to help Philip, but could initially be reassured about this. The political plan of their general Titus Quinctius Flamininus provided that there should no longer be any hegemonic power in Greece in the future. Flamininus absolutely wanted to avoid that the Seleucid king would now take the place of the previous hegemon Philip. Therefore, Rome and Antiochus tried in several conferences to delimit their spheres of interest, but could not achieve any success. Initially, the two great powers had no direct reason for a military conflict, but a "Cold War" developed between them between 196 and 192, during which they courted the favor of the Greek powers and cities.

Flamininus had proclaimed the freedom of all Greeks at the Isthmian Games in 196. In doing so, he threatened the political position of Antiochus, who appeared externally as the liberator of the Greek cities and the restoration of their autonomy. Ultimately, the Romans gave him the choice of either giving up Thrace permanently, whereupon he would be given a free hand in Asia Minor, or continuing to tolerate Roman influence there. Antiochus did not respond to this, however, because he wanted control over both Thrace and Asia Minor.

Rome had been allied with the Attalids of Pergamon since the two wars against Philip. From 197 onwards, the Empire of Asia Minor was ruled by Eumenes II , who was very interested in Rome pushing the Seleucid influence back to its borders. Conversely, Antiochus allied himself with the Aetolian League , which was hostile to the new Roman order in Greece. Although the Aitolians had fought together with Rome against Philip, their territorial gains were smaller than hoped, since Flamininus wanted a balance of power in Greece. The Aitolians could only hope with the help of the Seleucids to survive in a war against Rome, which is why they assured Antiochus that all of Greece was just waiting for him to come over from Asia for liberation.

In 195 the Carthaginian general Hannibal had to leave his hometown and received asylum at the Seleucid court, whereupon the relationship between Rome and Antiochus continued to cool. In the elections to the consulate in 194 Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus was elected, who had defeated the Carthaginians in the Second Punic War . Antiochus, however, made little use of Hannibal. This asked the Seleucid king for troops for a political overthrow in Carthage. Then Hannibal could dare a second invasion of Italy, while Antiochus would have a free hand to change the situation in the Aegean region in his favor. The Seleucid rejected this plan, however, because he himself would only have played a minor role, which was not compatible with his image of rulers.

The Aitolians tried to provoke a war in Greece in the spring of 192 by leading revolts in the important cities of Demetrias , Chalkis and Sparta . They only succeeded in Demetrias, where an anti-Roman government could be installed. The Romans then indicated that they would not accept the city's rubbish. Antiochus finally decided to accept the Aetolian invitation to "liberate" Greece in order not to allow any further strengthening of the pro-Roman forces. The king was inadequately armed militarily, but in the autumn he dared an invasion with 10,000 men and ended up near Demetrias. This started the Syrian-Roman War .

The Syrian-Roman War (192-188)

The Seleucids and Aitolians tried to take control of larger parts of Greece before the Roman counter-attack would take place. By the spring of 191 Antiochus was able to prevail in Chalkis, Boeotia , Elis , as well as parts of Thessaly and Acarnania . Apart from the Aetolian League, he could only receive military support from King Amynander of Athamania . During the winter Antiochus married a Chalkidian woman to show his connection to Greece. Philip of Macedonia decided against Antiochus and in favor of his former opponent Rome, as he was promised the partial restoration of his old power. The Achaean League also sided with the Romans.

The Roman troops under the command of Manius Acilius Glabrio advanced against Thessaly with Macedonian support, whereupon Antiochus had to retreat south and holed up in Thermopylae . Glabrio attacked the 10,000 Seleucid and 4,000 Aitolian warriors with about 25,000 soldiers and was finally able to force the breakthrough. Antiochus did not try to save his position in Greece, but withdrew to Asia Minor. However, the Aitolians continued the war with financial support from the Seleucid King.

The new consul Lucius Cornelius Scipio was supposed to succeed Antiochus in Asia Minor, but first of all the naval rule had to be achieved. The Roman fleet commander Gaius Livius Salinator was able to defeat the Seleucid Admiral Polyxenidas near Korykos in autumn 191 together with the Pergamene fleet . Antiochus did not give up the naval war, however, and had new ships built during the winter, with which Polyxenidas defeated the Rhodians, allied with Rome, at Panormos . In addition, Hannibal was commissioned to assemble a second fleet in Phenicia. This was subject to a Rhodian fleet near Side in the summer of 190 . After Salinator's successor, Lucius Aemilius Regillus , had also defeated Polyxenidas' fleet in the Battle of Myonessos with Rhodian support , the naval war was decided in favor of Rome.

Lucius Scipio, who was accompanied by his brother Scipio Africanus, marched through Macedonia to Thrace, occupied Lysimacheia, abandoned by the Seleucids, and crossed the Hellespont unchallenged . At the end of 190, around 50,000 soldiers from both sides met in the Battle of Magnesia . Antiochus led the cavalry and broke through the Roman ranks, but could not come to the aid of his own infantry. The opposing cavalry was under the command of the Pergamene King Eumenes, who attacked the Seleucid phalanx from the side. After Antiochus 'war elephants were driven back by the Roman infantry, these broke into their own ranks, whereupon Antiochus' army fled.

The military decision was followed by long negotiations that ended with the Peace of Apamea in 188 BC. Were completed. Antiochus lost all lands north and west of the Taurus , so that of the possessions of Asia Minor only Cilicia remained in his possession. The ceded territories fell to the Roman allies Pergamon and Rhodes or became independent if they had come to terms with Rome in time. The Seleucids were forbidden from any foreign policy in Asia Minor. The fleet was reduced to ten ships, which were not allowed to go beyond Cape Sarpedon, while the possession of war elephants was completely prohibited.

In addition, Antiochus undertook to pay heavy reparations. In total, the Seleucid Empire had to raise 15,000 talents of silver in twelve years - 50 percent more than Carthage after the Second Punic War and this in a quarter of the time. Antiochus and his sons were able to raise this amount, but had to levy high taxes. This was ultimately doomed to Antiochus the Great when he was slain in 187 while sacking a temple in Elymais .

politics

The Seleucids had lost control of large parts of the original empire before Antiochus' reign. Yet they had never given up their claims to these areas. Antiochus the Great made the recovery of what was lost his primary foreign policy goal. He did not see himself as a conqueror, but as a restitutor orbis (restorer of the empire). The expansion of the Seleucid Empire at the death of the founder of the dynasty Seleucus I Nicator , who was the great-great-grandfather of Antiochus the Great, was regarded as normal .

The lost territories were now owned by the competing Hellenistic dynasties or had become independent. Antiochus proceeded relatively slowly with its expansion and usually waited for domestic political weaknesses of its opponent before venturing out to war. He did not go to extremes (except with rebels like Achaios), but limited himself to the annexation of a certain province and spared its main lands. If, from Antiochus' point of view, the conquest of the entire country could not be prevented because it had previously belonged to the Seleucid Empire in full, he left the previous owner in office and dignity and was recognized as the superior Oikos ruler (world). In this way, Antiochus' empire saved energy, but also created a foreign policy situation in which almost all neighboring powers had an interest in the failure of the Seleucids.

Antiochus saw himself in the tradition of the Macedonian army kings, whose territorial legal claims were based on the belief in spear-acquired land - in fact, on the right to victory. In contrast, all losses suffered by the dynasty from neighboring states were considered robbery, even though they operated on an equal legal basis. However, Antiochus did not care about this contradiction. He shared this egocentricity with most of the other Hellenistic kings, who only concluded temporary border treaties and tried to enlarge their empire when the opportunity arose. Nonetheless, Antiochus the Great was not as volatile in foreign policy as Philip V of Macedonia, for example, but planned for the long term and waited for the right opportunity when conquered.

Legacy

He bequeathed his sons Seleucus IV and Antiochus IV an empire which, although still vast in size, was strongly tied to the person of the late king. The provinces of the east (Babylonia, Elam, Medien, Persis) tried several times to break away from the empire and were finally conquered between 141 and 138 by the rising new power, the Parthian Empire .

The most important new acquisitions by Antiochus the Great had been the provinces of Koilesyria and Palestine. However, these were lost as a result of the Jewish Maccabees uprising around 165. In the final phase of the Seleucid dynasty, its territory was limited to Syria, but it was only a Roman client state , which finally came about with the establishment of the Roman province of Syria in 63 BC. Was eliminated by Pompey .

literature

- Boris Dreyer : The Roman rule of nobility and Antiochus III. (205 to 188 BC). Clauss, Hennef 2007, ISBN 978-3-934040-09-0 (also habilitation thesis, University of Göttingen 2003).

- John D. Grainger: The Roman War of Antiochus the Great . Brill, Leiden / Boston 2002, ISBN 90-04-12840-9 .

- John Ma: Antiochus III and the Cities of Western Asia Minor. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1999, ISBN 0-19-815219-1 .

- Hatto H. Schmitt : Antiochus the Great. In: Kai Brodersen (ed.): Great figures of Greek antiquity. 58 historical portraits from Homer to Cleopatra. CH Beck, Munich 1999, pp. 458-464, ISBN 3-406-44893-3 .

- Hatto H. Schmitt: Investigations into the history of Antiochus the great and his time. Steiner, Wiesbaden 1964 (also habilitation thesis, University of Würzburg 1963).

Footnotes

- ↑ Omar Coloru: La forme de l'eau. Idéologie, politique et stratégie dans l'Anabase d'Antiochos . In: Christophe Feyel, Laetitia Graslin-Thomé (ed.): Antiochos III et l'Orient . Association pour la diffusion de la recherche sur l'Antiquité, Nancy 2017, pp. 299–314.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Seleucus III |

King of the Seleucid Empire 223–187 BC Chr. |

Seleucus IV |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Antiochus III. |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Antiochus III. the great |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | King of the Seleucid Empire |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 242 BC Chr. |

| DATE OF DEATH | 187 BC Chr. |