Kingdom of Pontus

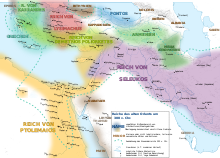

The kingdom of Pontus was on the south coast of the Black Sea . It was founded by Mithridates I. Ktistes in the 3rd century BC. Founded in BC and existed until the 1st century BC. The kingdom reached its greatest expansion under the rule of Mithridates VI. , who controlled Cappadocia , Bithynia , Galatia , Colchis , the Roman province of Asia and the Bosporan Empire . After a long power struggle between the Roman Empireand Pontus, the kingdom was finally partially incorporated into the Roman Empire and continued to exist there as the province of Bithynia et Pontus . The eastern part of Pontus continued to exist as a client kingdom of Rome until it was abolished under Nero.

Uncertain key data

A kingdom is defined by its kings. In the case of the Kingdom of Pontus, the number and order of the kings is not fully understood to this day. The open questions include unambiguous periods of reign and - as a result - the assignment of individual traditional acts. The established opinion of science is based on the tradition of Georgios Synkellos , who lists 218 years of reign of the Pontic kings in his world chronicle. In one construction one takes the death of Mithridates VI. as the end of the kingdom of Pontus. This would mean that the empire of 281 BC BC to 63 BC Exists.

history

Roots of the kingdom

From Pontos Euxeinos , the Black Sea, the term Pontos migrated to its southeastern coast and to the region , which was shaped into a social structure by the Mithridates in the 3rd century to the middle of the 1st century. Pontos is a term for space (geography) and territory (politics). The origin of a Pontic people is in the dark. The inhabitants of the area only referred to themselves as pontiers when the Romans annexed the area as a province after the end of the kingdom.

The traces of the ancestors of the Pontic kings lead to Kios , a small town on the south bank of the Marmara Sea in Mysia . The Mithridatic dynasty is handed down in three places by the Greek historian Diodorus . In one of the three places he mentions the murder of a member of the royal family named Mithridates by Antigonus I Monophthalmos . This Mithridates ruled kios in Mysia for 35 years. His successor with the same name extended the rule to Cappadocia and Paphlagonia . Diodorus uses the words "dynasty" and "kingdom" elsewhere. These names do not indicate satrapies . In addition, Kios is not referred to as part of a Persian fiefdom and there is no evidence of satraps or a Persian dynasty. The research opinion, which has been established for a long time, could not classify the significance of these indicators and therefore always spoke of the satraps of Kios. Another aspect has also not been considered so far. The tributary kios paid a tax that was very modest compared to other cities. After this fact came into the consciousness of the research, it was concluded that the city had no great economic and political importance.

The kingdom of the Mithridatic dynasty could not be limited to small towns like Kios, as previously assumed, but - so the conclusion - extended over the whole of Mysia in the form of an inheritable principality.

But the territory of the Mithridates extended even further. Polybius describes it to the Black Sea along an area that to them by Darius I had been given. It is the region of Mariandynia with its center Bithynium, later Claudiopolis . At the same time Ariarathes I ruled as satrap over Cappadocia. It appears that what would later become the kingdom of Pontus was originally ruled by these two families.

Family tree of the Mithridates

The remarks of Mithridates VI come from Justin , who relies on Pompey Trogus . Eupator, who traces his family back to Alexander the Great and Seleucus I on his mother's side and to Cyrus II and Darius I on his father's side . This claim to royal lines was denied him by historians until recently. Instead, they resorted to the Phrygian satrap Ariobarzanes and built a family tree of the Mithridates with the little available source material, which subsequently led to many inconsistencies that could never be completely resolved.

A more recent study works with the same source material, but reassembles the material and comes to a completely new interpretation that meets the requirements of Mithridates VI. Eupator could agree. What is special is the fact that she brings all sources into agreement with her hypothesis. The family tree of Bosworth and Wheatley is shown with slight changes in the following graphic.

The time of kings

The term "Kingdom of Pontus" or "Pontic Kingdom" was created by posterity. The kings themselves and contemporaries did not use this term, but spoke of the "kingdom of the king". It is part of the Persian tradition that ancestry, not territory, gives a king his title.

The emergence of the Greco-Iranian monarchy left its mark on the territory and given it an identity. The "Pontic" name was probably given to it by the Persians or the Seleucids. But Polybius still speaks of a Pontic Cappadocia when he talked about the wedding of Antiochus III. with Laodike, Mithridates' II daughter, and Strabo tells: “As for Cappadocia: It came, divided by the Persians into two satrapies, into the possession of the Macedonians, who sometimes gladly, sometimes reluctantly let it happen that from the Satrapies became kingdoms; of those they called the one, Cappadocia 'in the strict sense or Cappadocia on Taurus' or even, Großkappadokien', the other Pontos' (Other, Cappadocia on Pontus'). "Only Julius Caesar survived the first Roman source" a Triumph ex Ponto ”.

The kings created a uniform administration in their empire and structured the area with economic, military and religious centers. “Despite a multitude of languages, traditions and ways of life, we must assume that at the time of Mithridates' death, VI. Eupator the Pontic Empire had achieved a certain symbiosis of Greek, Iranian and Anatolian elements, which can be described as 'Pontic'. "

Mithridates I. Ktistes

Mithridates Ktistes is considered to be the founder of the kingdom, whose exact hour of birth is not clear. He fought in the Diadoch Wars on the side of Eumenes and switched to the side of Antigonus I Monophthalmos after the Battle of Gabiene . In 302 BC Because of the warning of his friend Demetrios he fled to Paphlagonia, where he lived between 302 and 266 BC. Ruled. During this period he proclaimed himself the first king of Pontus.

Ariobarzanes

Little is known about Ariobarzanes ' reign. He must have shared his father's last years of rule with him. He is mentioned in connection with the conquest of Amastris and in business with the Galatians .

Mithridates II

Ariobarzanes' son, Mithridates II , was still a child when his father died. The Galatians tried to exploit the weakness of the empire and crossed the borders of Pontus. The attack was repulsed with the help of Heraclea Pontike . In order to consolidate his country in terms of foreign policy, Mithridates II later pursued an active marriage policy. He himself married the sister of Seleucus II and married his daughters to both Seleucus' son Antiochus III. as well as with Antiochus Hierax. The royal roots of the Mithridatic family could have played the background of the weddings between the Seleucids and a non-Greek royal family unknown at the time. In the fraternal dispute between Antiochus Hierax and Seleukos II , Mithridates II supported Antiochus Hierax and won the battle of Ancyra with him . The exact year of death of the third Pontic king is not known.

Mithridates III.

About the reign of Mithradates' son Mithradates III. very little information has come down to us. Some scientists suspect that he is identical to Mithridates II. But that would lead to a reign of Mithridates II that is incredibly long. Second, the number of Pontic kings of eight handed down by Plutarch and Appian would not be kept. Finally, the five rock tombs in Amaseia, the last of which is unfinished and ascribed to Pharnakes, cannot be assigned.

Pharnakes I.

The fifth king was Pharnakes , who expanded the kingdom and moved the capital from Amaseia to Sinope. He was the first of the Pontic kings to have diplomatic contact with Rome. At the end of his reign around 155 BC Century stretched the kingdom from Amasra to Cerasus .

Mithridates IV. Philopator Philadelphos

The sixth ruler, Mithridates IV. Philopator Philadelphus , was the brother of Pharnakes. It is not exactly known when he came to power. It is said that he supported Attalus II in the fight against Prusias II of Pergamon. But he took a much less aggressive course in foreign policy than his predecessor. An inscription on the Capitol commemorates his friendship and alliance with Rome.

Mithridates V. Euergetes

Mithridates V. Euergetes was the son of Pharnaces. His wife, Laodike , may have been the daughter of Antiochus IV . In 149 BC He supported Rome in the third Punic War and 133–129 BC. Against Aristonikos . Phrygia was given to him in gratitude . This gesture was controversial in Rome and Gaius Gracchus accused him of bribing Roman politicians. Mithridates V Euergetes was the first king to have Greeks occupy important positions. The king became 123 BC. Murdered in Sinope.

Mithridates VI. Eupator

Under the last Pontic king, Mithridates VI. Eupator saw the kingdom flourish and fall. In three military conflicts with the Roman Empire , he challenged the masters of the western world. The Mithridatic Wars lasted nearly 30 years and ended with the victory of Rome and the end of the kingdom.

After the kingdom

The western part of the kingdom was annexed by the Romans and declared the new territory of the Roman double province of Bithynia et Pontus . The eastern part of the empire and the Bosporan empire continued to exist as a client state for the time being. During the civil war between Caesar and Pompey attacked the ruler of the Bosporan Empire Pharnakes II , the son of Mithridates VI. Eupator, 48 BC BC the Romans with the goal of retaking Pontus. After the Roman defeat at Nicopolis, Caesar defeated Pharnakes II in the battle of Zela and restored the previous balance of power.

society

At the end of the 2nd century and the beginning of the 1st century BC There were Greek cities scattered all over Asia Minor. With the Seleucids , the border between Greek civilization and rural Anatolia inland was softened. But the monarchies of Pontus, Cappadocia and Armenia were not involved in this process.

The dynasty in Pontos was Persian and with it most of the country. Greek cities existed on the Black Sea coast and the interior of the country was dominated by castles, villages and farms with pastureland. Lords and peasants lived in a feudal relationship to one another. But the kingdom of Pontus is also in Hellenism . It would therefore be of particular interest to see how Greek and Oriental cultures were expressed in the kingdom. Some opinions assume a complete Greek penetration that reached into the deepest valleys of the empire. This was a deliberate policy of the Pontic kings. Others see a conglomerate of different ethnic cultures held together by a Persian-influenced dynasty that has proven to be very flexible.

In a more recent study, the parameters that are suitable as indicators for the penetration of Hellenism are named. These are language, naming, myths, calendars, cultural and political institutions and social changes. In order to be able to make binding statements, however, there is still no source evidence for the Kingdom of Pontus.

administration

It is said that Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus founded many cities in the interior of the defeated kingdom of Pontus. It was automatically assumed that there were few cities among the Mithridates and that they themselves had not founded any new ones. More recent findings show that the Roman general gave the previously settled areas the character of Greek cities and was thus able to smash the previously existing administrative structures of the kingdom.

As evidence of a central administration in the Kingdom of Pontus, it is proposed to take the imperial minting of coins. Ten different locations in Pontos with the Halys River as a border could have produced uniform coins: Amaseia, Amisos , Chabakta, Gazioura, Kabeira, Komana, Laodikeia, Pharnakeia, Pimolisa and Taulara. There are also three locations beyond the Halys: Sinope, Amastris and probably Dia west of Herakleia. Common to all locations are strong fortifications. A few of them give no indication of urban life and two of them (Chabakta and Taulara) disappeared after the Roman conquest. It is believed that all of these places played an administrative role in the kingdom of Pontus.

Strabo describes the administration of Cappadocia, which was divided into ten districts (strategiai). In many places he highlights similarities between the kingdom and Cappadocia. It is therefore strongly assumed that similar structures existed among the Mithridates, although there is no direct evidence for this, and it is assumed that the places of the imperial coinage were the seats of the prefects ( strategos ). The forts spread all over the country served as a network, which no longer had any functionality after the conquest of the Romans, but on the contrary posed a threat.

A study from 1974, which all known persons at the Pontic royal court under Mithridates VI. Eupator lists generals and other military officers. There are also philosophers, a court musician, his perfumer and the personal doctor. Administrative and religious office holders are not listed. Eunuchs apparently played a major role at court and in administration. The most famous is Bacchus , who was killed by Mithridates VI. In view of the impending defeat, Eupator was given the task of killing the women in the palace. But other names are missing, as if they didn't exist.

religion

The diversity of society in the Pontic Kingdom is expressed in religion. Local, Iranian, Greek, Egyptian and later, after the fall of the kingdom, Roman influences have been proven. Deities who transplant from one cultural environment to another change their characteristics, their appearance and, gradually, their identity. Whether there is syncretism must be examined individually for each deity. In a study by Artemis Anaïtis and Mên in the Kingdom of Pontos, it is found that there is evidence of a gradual adaptation of original properties with local peculiarities of the environment. So there was no syncretism in the kingdom of Pontus between the two deities.

The temple districts, also called temple states by historians, represent a specialty. The most famous temple districts of the Kingdom of Pontos are Ameria, Komana Pontika and Zela , which were located in the central region of the Kingdom. The contemporary Strabo called it a village town (Ameria), a holy district (Zela) and a city (Komana Pontika).

There is no doubt that in Strabon's time the most important public religious rites in the Pontic region were derived from the Achaemids . They were promoted by the Mithridates and in return they strengthened the legitimacy of the dynasty. The coins show how the Mithridatic kings were able to unite the complex culture of their empire and bind it to their dynasty.

Deities

The historian Eckart Olshausen has compiled the deities and their meanings for the region. Most of the gods and goddesses listed have Greek names such as Ares , Athene , Dionysus , Helios , Hera and Zeus . Mithridates VI. Eupator promoted worship in his kingdom. It is believed that he wanted to win the sympathy of the Greek population. For example, the cult of Apollo , one of the most popular gods on the Black Sea, received official royal status. There were also Egyptian ( Sarapis and Isis ), Persian and local deities such as Anaitis , Ma and Men Pharnaku . Greek heroes ( Perseus and Heracles ) played a major role in the Mithridates.

Of the forty listed gods and goddesses in the study, eighteen are of importance for the time of the kingdom of Pontus. Of the deities classified as significant, eleven were promoted by the Mithridates. Some selected deities are described below.

Anaïtis

Strabo tells of an identity that unites Armenian, Median , Persian and Anatolian types of the same deity. He calls her Anaïtis, the Hellenistic form of Anahita . The same identity is also called "Artemis Persike", "Persian Diana", "Artemis Medeia", "Thea Anaïtis", "Meter Anaïtis", "Artemis Anaïtis" or "Thea Megiste Anaeitidi Barzochara". Anaïtis originally has Persian roots, which is not undisputed in research. In the course of time the various names, called polyonymy , aided the process of the respective cultural environment , endowing the deity with local attributes and functions and increasing its power.

In Anatolia, Iranian traditions and ethnicities endured throughout the Hellenistic and well into Roman times. Anaïtis was not only revered by the pushed back Persian elite, but also by mixed communities. The reason could be structural changes that have taken place since the beginning of Hellenism. The Anaïtis worship in Anatolia lost contact with the Persian centers and acquired the character of "diaspora cult sites". The isolation led to changes in the religious orientation and the cult opened up to foreign influences. Worship shifted from an ethnicity-based system of religion to a "universal" belief system that included divine appearances, personal contact, and metaphysical power.

Anaïtis was the cult center of the priestly state of Zela. Strabo attributes a great festival that was celebrated in Zela to the victory of a Persian general over the Saks . According to another tradition, the festival of Babylon was spread throughout the Middle East with the Anais cult.

Dionysus

Dionysus was worshiped as the god of fertility in various Greek coastal cities of the kingdom. A Dionysus cult has been isolated since the 3rd century BC. Passed down by Amisos and is there from the 2nd century BC. Became popular. As the god of viticulture and agriculture, he was highly valued in the city with its fertile hinterland. Investigations of the traditional terracotta figures from Amisos show how popular the deity has been as a theme for masks and protomes . Dionysus was mostly represented young and in two versions (Dionysus Taurus and Dionysus Botrys), which identified him as the son of Zeus and as the guardian of wine.

A Dionysus cult is also proven in Kerasus and Trapezus . The hinterland of Trapezus was also very fertile and the city proud of its viticulture.

The last Pontic king, Mithridates VI, used not only Eupator but also the nickname Dionysus. Although the name is not listed on the coins, the god himself or his attributes such as cista , thyrsos or panther are shown. Mithridates VI. Eupator often had himself depicted as Dionysus based on the Alexander coins with a similar hair style, slightly open mouth and upward looking gaze to emphasize his descent from the famous Macedonian ruler. Portraits of Mithridates VI Eupators were so similar to Alexander's that they even led to confusion in research in the case of the bust of "Alexander Schwarzenberg".

Ma

The veneration of Ma is passed down by the geographer Strabo as well as through coins and inscriptions. She is identified with the Greek goddess Enyo and the Roman Bellona .

Ma is a warlike goddess who is represented with a shield and a halo. She is considered the "goddess of victory". Exactly when it appeared in Anatolia is unknown.

The most famous pilgrimage site of the Ma was the temple district of Komana Pontika. Twice a year, large festivals were held there, during which the cult statue was led out of the temple in procession. Strabo describes the services for Ma as ecstatic. A special feature of the worship was the temple prostitution, which Strabo describes in detail and he tells how a daughter of an Armenian nobleman had consecrated her services to the goddess.

Men Pharnaku

Men is the god of the moon and always carries a crescent moon on his shoulder, which is his symbol. He is dressed in Phrygian clothes with a cap, trousers, boots and a coat.

One study describes the deity as "Men: a Neglected Cult of Roman Asia Minor". The many cult places for men in the western part of Asia Minor are shown in an impressive map. The deity is passed down through inscriptions and coins. The source material is supplemented with terracotta or bronze statues, gemstones and a few art objects. With over 450 types of coins from almost 66 cities or government agencies, the cult has a presence in western Asia Minor that overshadows most of the other so-called "oriental" gods.

The spread of cult sites shown in the study decreases towards the east and in the kingdom of Pontos only Pharnakeia ( Ameria (Pontos) ) is registered as a cult site. The meaning of the name Men Pharnaku there is controversial. Most of the time Pharnaku is viewed as a genitive and the epithet is read as Men des Pharnakes , the fifth king of Pontus. There is no archaeological evidence for Men, but there are coins of him that were minted in Pharnakeia.

A crescent moon with an eight-pointed star can often be seen on the Pontic coins . The two characters are attributed to Men and Zeus Stratios, who is identified with the Persian god Ahura Mazda. They occur so often that there is talk of a Mithridatic "family coat of arms". Other researchers extended the symbolism to the whole kingdom of Pontus.

Eckhart Olshausen asks the following question:

"So if we assign the crescent moon to the Pontic men and the star to the Iranian Ahura Mazda, do we possibly have to do with the combination of both symbols with the attempt to connect the two most important ethnic elements in Pontus to the royal house of the Mithriadatic?"

Nike

The goddess of victory Nike was depicted on coins in the kingdom of Pontus. The cities of Amisos, Komana Pontika, Kabeira and Laodikeia provided the coins on behalf of King Mithridates VI. so that one can speak of a uniform imperial coinage. An actual Nike cult cannot be assumed. With the Gorgoneion depicted on the obverse in the center, the coins refer to the Perseus legend and thus to the mystical origin of the royal house and its descent from the Persian kings.

Perseus

Perseus is considered to be the progenitor of the Persian kings. With the claim of the Mitridates to royal Persian ancestors, he was therefore represented as the founder of the dynasty. Therefore there are many references to the Perseus saga on coins of both kings and imperial coins. The portrait of Perseus sometimes takes on distinctly individual features that refer to Mithridates VI. refer. The apotheosis later resigns in favor of the apotheosis as Heracles .

Zeus

One is tempted to bring the closeness to Zeus to the figure of Mithridates VI. Tie Eupator. That would not be correct, since already under the reign of Mithridates III. Coins have survived that connect him with Zeus and his wife Laodike with Hera and associate the two deities as protectors of the Mithridatic dynasty. The connection to the highest Greek deities was established by Mithridates IV, V. and VI. continued.

Zeus had many nicknames in Pontus and was endowed with many attributes, but his central meaning was that of protector: protector of houses, villages and cities, of walls, fortifications and castles. He also protected the grain and the people from the forces of nature. In the kingdom of Pontos, Zeus culminated in Zeus Soter, who was especially venerated in the Greek cities. But the official cult found expression in Zeus Stratios. Appian reports how Mithridates VI. Eupator offered him a sacrifice:

“This [Mithridates], after he had also attacked and driven away all the garrisons of the Murena in Cappadocia, brought a sacrifice to war Jupiter on a high mountain, ordered by his ancestors, for which he had piled up a large pile of wood. Wood is first brought to him by the kings, then a second, lower pile of wood is built around it, on which milk, honey, wine, oil and all kinds of incense are poured, on the low bread and food for a meal for those present (in whichever way the kings of Persia organized a festival of sacrifice in Pasargada) and set the wood on fire. Because of its size, the flame is seen a thousand stadia away from the boatmen, and because of the heat of the air one should not be able to approach for several days. The king celebrated this festival of sacrifice according to the custom of his fathers. "

Sources indicate that Zeus Stratios was worshiped by Persians, Anatolians, Greeks and, after the defeat of the kingdom, by Romans. Greeks identified their supreme god with local Anatolian deities, while the Mithridates identified with Ahura Mazda . The result was a Greco-Iranian cult of Zeus Stratios with both Anatolian and Persian characteristics.

Temple districts

The origins of the temple precincts of the kingdom of Pontus probably go back to the Hittites . Under the Mithridates they retained their economic and political independence and were promoted by them. They had their own income and managed the area autonomously. The area of the temple precinct also likely included land that belonged to an independent rural population: individual village areas, associations of village areas, and land belonging to tribes. The wealth under divine protection meant that the temple precincts played an important role in the economic life of the region. Income and taxes were used as loans to villages and individuals, so that the temple districts functioned as "temple banks".

Priests were responsible for the administration of the temple precincts and came right after the king. The office of high priest was a gift from the king for special merit. Dorylaos, for example, a distant relative of Strabo, received the office of high priest from Mithridates VI. Eupator for his services. Consecrated slaves, called hierodules , did the work in the district. They were subordinate to the high priest and belonged to the temple. Therefore they could not be sold. In addition to the slaves, prostitutes played a role who had dedicated themselves to the deities Ma and Anaïtis.

The deities Anaïtis, Ma and Men Pharnaku were of great importance in the religious life of the kingdom. Anaïtis was venerated in the temple district of Zela, whose temple dates back to the Achaemenid period (4th century BC). Sacred rites performed there were taken very seriously in the kingdom. Once a year the big festival Sakaia was held, at which the defeat of the Saka was celebrated. Strabo narrates it as a festival with a Bacchic character, at which men in Scythian clothes and women drank wine and celebrated exuberantly.

A second large temple district was Komana Pontika , which was also an important marketplace for the region. About inscriptions from the 2nd century BC It is said that the district had the right to asylum, was sacred and that the area could not be violated. These statements are interpreted as the legal sovereignty of the district. The temple of Komana Pontika was dedicated to Ma, who served 6,000 consecrated slaves. Festivals for the deity were held to get the deity benevolent so that the district's trade and development could flourish.

The "village city" (Komepolis) Ameria as the third important temple district housed Men Pharnaku. According to Strabo, the place was important to the kingdom because the kings swore their oath "by the king's Tyche and Men Pharnaku" in this temple area.

Overall, there are few sources about the temple precincts for the time of the kings. The most important source is Strabo , who left a detailed description of Komana Pontika.

Kings of Pontus

The composition of the kings is based on the currently established opinion of the researchers. The weaknesses and inconsistencies are discussed again and again in research. A final version is not yet in sight due to the unchanged source situation. Details can also be found in the respective articles of the kings.

| king | Beginning of rule | End of rule |

|---|---|---|

| Mithridates I. Ktistes | 281 BC Chr. | 266 BC Chr. |

| Ariobarzanes | 266 BC Chr. | approx. 258 BC Chr. |

| Mithridates II | 256/250 BC Chr. | approx. 220 BC Chr. |

| Mithridates III. | approx. 220 BC Chr. | approx. 185 BC Chr. |

| Pharnakes I. | approx. 185 BC Chr. | approx. 155 BC Chr. |

| Mithridates IV. | approx. 155 BC Chr. | 152/151 BC Chr. |

| Mithridates V. | 152/151 BC Chr. | 120 BC Chr. |

| Mithridates VI. Eupator | 120 BC Chr. | 63 BC Chr. |

Sources

Before Mithridates VI

In his standard work Mithradates Eupator. King of Pontus , published in Leipzig in 1895, Théodore Reinach summarizes the traditional sources on the first Pontic kings. It refers to Georgios Synkellos , who refers to Apollodorus and Dionysius of Halicarnassus in his world chronicle . In addition, he lists Pompey Trogus , who wrote an overview of the kingdom of Pontus. All the original sources have been more or less lost. Apart from a few scattered notes by Polybius , Memnon of Herakleia , the coins are the main source of information.

An attempt was made to consolidate conflicting sources via coins and inscriptions by adding two additional kings, Mithridates III. and IV., were introduced, but their existence could not be conclusively proven.

In a recent numismatic study that compiled the well-known Pontic coins with representations of kings, 64 tetradrachms , 18 drachms and 4 staters were examined.

| king | Staters | Tetradrachms | Drachmas | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| no | obv | no | obv | no | obv | |

| Mithridates III | 2 | 2 | 19th | 5 | 2 | 1 |

| Pharnakes I | 1 | 1 | 24 | 9 | 16 | 5 |

| Mithridates IV | 1 | 1 | 14th | 6th | - | - |

| Mithridates IV and Laodike | - | - | 5 | 2 | - | - |

| Laodike | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - |

| Mithridates V | - | - | 1 | 1 | - | - |

| Total | 4th | 4th | 64 | 24 | 18th | 6th |

On the interpretation of the coins, François de Callataÿ writes :

“Mistakes were often made. [...] The numbering of the kings is also merely an illusion. The sequence of kings itself was by no means secure when, finally, at the end of the 19th century, Théodore Reinach (1860–1928) took a serious look at the subject. But Reinach himself changed his mind with the discovery of new pieces of evidence. And, recently, Harold Mattingly dared to propose a radical change in the sequence of kings (attributing the coins of Mithridates III to Mithridates IV, that is after the coinage of Pharnakes). "

The author finally agrees with the established opinion about the order of kings, which was already established by Théodore Reinach.

The study shows that today's research works with essentially the same source material as the historians 100 years ago. In order to narrow the gaps, scientists have high hopes for archaeological excavations in Anatolia , which began at the turn of the millennium. The 2015 publication, which contains 35 research reports on excavations, states that archeology is far from exhausting the area's potential.

review

The kingdom of Pontus has long been overshadowed by its neighbors: Bithynia, Cappadocia and the Seleucid Empire . It was only the outstanding personality of Mithridates VI. Eupator made the kingdom famous. Scholars such as Theodor Mommsen and Théodore Reinach viewed him with the prevailing image of orientalism in the 19th century and dubbed him a cruel oriental despot, an Ottoman sultan and an opponent of western civilization. Accordingly, the kingdom of the Pontic kings could not stand up to any comparison with western culture. The Greek presence in language and culture in the kingdom was dismissed as superficial, like wearing a dress and taking it off. Theodor Mommsen wrote the following about the last king of Pontus:

“Even more significant than through its individuality, it became through the place in which history has placed it. As the forerunner of the national reaction of the Orient against the Occidentals, he opened the new struggle of the East against the West; and the feeling that one's death was not at the end but at the beginning remained with the vanquished as well as the victors. "

It is striking how many times archaeologists and historians mention the poor source situation for the kingdom of Pontus. There is a lack of archaeological studies and finds, inscriptions and other local lore. Jakob Munk Højte describes the situation as follows: "Since we largely lack local sources from the Hellenistic period, such as inscriptions, we only hear about Pontic affairs when events influenced the outside - and more specifically the Greek and Roman world." The figure of Mithridates VI. Eupator was able to attract the attention of the Greek and Roman historians of the time. These created a picture that, from Théodore Reinach and Theodor Mommsen, became formative for science well into the 20th century.

The pendulum has since turned back in favor of a more positive assessment and today we are given a picture of the kingdom that, with its last king, defended the Greeks against Roman aggression. This reflects the contemporary critical view of the history of the Roman Empire.

In the foreword to “Black Sea Studies 9” on “Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom”, the editor, Jakob Munk Højte, writes that the poor local sources, bias through ideological concepts or the zeitgeist force statements about the kingdom and descriptions of its kings to be treated with the greatest caution today.

literature

- AB Bosworth, PV Wheatley: The origins of the Pontic house. In: The Journal of Hellenic Studies 118, 1998, pp. 155-164.

- Prentiss S. De Jesus: Metal Resources in Ancient Anatolia. In: Anatolian Studies. Journal of the British Institute of Archeology at Ankara Vol. 28, 1978, pp. 97-102.

- Jakob Munk Højte (Ed.): Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom (= Black Sea Studies 9). Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, ISBN 978-87-793-4443-3 .

- Georgy Kantor: Mithridates I – VI of Pontos. In: The Encyclopedia of Ancient History . Volume 8, Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2013, p. 4544.

- Brian C. McGing: The foreign policy of Mithridates VI Eupator, King of Pontus. Brill, Leiden 1986, ISBN 90-04-07591-7 .

- Brian C. McGing: The Kings of Pontus. Some Problems of Identity and Date. In: Rheinisches Museum für Philologie 129, 1986, pp. 248-259 ( online ).

- Stephen Mitchell : In Search of the Pontic Community in Antiquity. In: Alan K. Bowman et al. a. (Ed.): Representations of Empire: Rome and the Mediterranean World. Oxford 2002.

- Eckart Olshausen : Heroes and their cults in Pontos - a first report. In: Rise and Decline of the Roman World (ANRW) , Part II: Principat, Volume 18, 3. De Gruyter, Berlin, New York 1990, pp. 1865-1906.

Web links

- http://www.kavehfarrokh.com/iranica/parthian-era/professor-brian-mcging-mithradates-vi-eupador-of-the-pontus-kingdom/

- Greeks Numismatics. Retrieved May 11, 2019 .

Individual evidence

- ^ The Dynastic History of the Hellenistic Monarchies of Asia Minor According to the Chronography of George Synkellos . Oleg L. Gabelko, in Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom. Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, p. 48; Georgy Kantor: Mithridates I – VI of Pontos. In: The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, Volume VIII. Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2013, pp. 4544-4545.

- ↑ For a detailed discussion of the name, see the chapter entitled "Names and Identities in the Pontus" in the Stephen Mitchell article: In Search of the Pontic Community in Antiquity. In: Alan K. Bowman et al. a. (Ed.): Representations of Empire: Rome and the Mediterranean World. Oxford 2002.

- ↑ Anica Dan: Pontic Ambiguities. In: eTopoi Journal for Ancient Studies Volume 3, 2014, p. 44.

- ↑ Diodorus 15.90.3; 16.90.2; 20.111.4; A. B. Bosworth, P. V. Wheatley, The origins of the Pontic house. In: The Journal of Hellenic Studies 118, 1998, p. 155.

- ↑ Diodorus 20.111.4.

- ↑ A. B. Bosworth, P. V. Wheatley, The origins of the Pontic house. In: The Journal of Hellenic Studies 118, 1998, p. 156.

- ↑ A. B. Bosworth, P. V. Wheatley, The origins of the Pontic house. In: The Journal of Hellenic Studies 118, 1998, p. 158.

- ↑ A. B. Bosworth, P. V. Wheatley, The origins of the Pontic house. In: The Journal of Hellenic Studies 118, 1998, p. 157.

- ↑ D. Burcu Arıkan Erciyas; Studies in the archeology of hellenistic Pontus: The settlements, monuments, and coinage of Mithradates VI and his predecessors. Dissertation, University of Cincinnati, 2001, p. 74.

- ↑ A. B. Bosworth, P. V. Wheatley, The origins of the Pontic house. In: The Journal of Hellenic Studies 118, 1998, p. 155.

- ↑ Brian C. McGing: The Kings of Pontus: some problems of identity and date. In: Rheinisches Museum für Philologie , new series, 129th vol., 1986, pp. 248-259.

- ↑ A. B. Bosworth, P. V. Wheatley, The origins of the Pontic house. In: The Journal of Hellenic Studies 118, 1998.

- ↑ Anca Dan: Pontic Ambiguities. In: eTopoi Journal for Ancient Studies Volume 3, 2014, p. 46.

- ↑ a b Anca Dan: Pontic ambiguities. In: eTopoi Journal for Ancient Studies Volume 3, 2014, p. 47.

- ↑ a b Anca Dan: Pontic ambiguities. In: eTopoi Journal for Ancient Studies Volume 3, 2014, p. 48.

- ^ Studies in the archeology of hellenistic Pontus: The settlements, monuments, and coinage of Mithradates VI and his predecessors. D. Burcu Arıkan Erciyas, Dissertation, University of Cincinnati, 2001, p. 78; Georgy Kantor: Mithridates I – VI of Pontos. In: The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, Volume 8. Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2013, pp. 4544-4545.

- ↑ a b c Georgy Kantor: Mithridates I – VI of Pontos. In: The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, Volume 8. Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2013, p. 4545.

- ↑ George Synkellos even mentions ten kings, see The Dynastic History of the Hellenistic Monarchies of Asia Minor According to the Chronography of George Synkellos. Oleg L. Gabelko, in Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom. Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, pp. 47-61.

- ^ Studies in the archeology of hellenistic Pontus: The settlements, monuments, and coinage of Mithradates VI and his predecessors. D. Burcu Arıkan Erciyas, Dissertation, University of Cincinnati, 2001, pp. 80-82.

- ^ Georgy Kantor: Mithridates I – VI of Pontos. In: The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, Volume 8. Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2013, pp. 4545-4546.

- ^ Georgy Kantor: Mithridates I – VI of Pontos. In: The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, Volume 8. Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2013, p. 4546.

- ^ Bithynia et Pontus. Karl Strobel, A. Roman times. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 2, Metzler, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-476-01472-X , Sp. 700-702.

- ↑ Light Nisa desk and Romanisation in Pontos-Bithynia: An Overview. Christian Marek, in Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom, Jakob Munk Højte, Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, p. 35.

- ↑ Light Nisa desk and Romanisation in Pontos-Bithynia: An Overview. Christian Marek, in Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom, Jakob Munk Højte, Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, p. 35.

- ^ Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom. Jakob Munk Højte, Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, pp. 7-8; see the article Pontic Greeks , which highlights a special social aspect of the region.

- ^ Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom. Jakob Munk Højte, Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, pp. 7–8.

- ^ The Administrative Organization of the Pontic Kingdom. Jakob Munk Højte, in Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom, Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, pp. 95-97.

- ^ The Administrative Organization of the Pontic Kingdom. Jakob Munk Højte, in Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom, Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, p. 98.

- ^ The Administrative Organization of the Pontic Kingdom. Jakob Munk Højte, in Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom, Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, p. 99.

- ^ The Administrative Organization of the Pontic Kingdom. Jakob Munk Højte, in Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom, Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, pp. 99-100.

- ^ The Administrative Organization of the Pontic Kingdom. Jakob Munk Højte, in Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom, Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, p. 103.

- ^ The Administrative Organization of the Pontic Kingdom. Jakob Munk Højte, in Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom, Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, pp. 101-102.

- ^ Iulian Moga: Strabo on the Persian Artemis and Mên in Pontus and Lydia. In: Gocha R. Tsetskhladze (ed.): The Black Sea, Paphlagonia, Pontus and Phrygia in antiquity: aspects of archeology and ancient history . Oxford 2012, p. 191.

- ^ Characteristics of the Temple States in Pontus . Emine Sökmen, in Mithridates VI. and the Pontic Kingdom, Jakob Munk Højte, Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, pp. 277-278; Eckhart Olshausen: Gods, heroes and their cults in Pontos - a first report. In: Rise and Fall of the Roman World (ANRW), Part II: Principat , Volume 18, 3. De Gruyter, Berlin, New York 1990, p. 1904.

- ↑ Stephen Mitchell: In Search of the Pontic Community in Antiquity. In: Alan K. Bowman et al. a. (Ed.): Representations of Empire: Rome and the Mediterranean World. Oxford 2002, p. 57.

- ↑ Eckhart Olshausen: Gods, heroes and their cults in Pontos - a first report. In: Rise and Decline of the Roman World (ANRW), Part II: Principat , Volume 18, 3. De Gruyter, Berlin, New York 1990, pp. 1865-1906.

- ↑ Eleni Mentesidou: The Terracotta Figurines of Amisos . Dissertation International Hellenic University, Thessaloniki 2015, p. 37.

- ^ Strabo on the Persian Artemis and Mên in Pontus and Lydia. Iulian Moga in Gocha R. Tsetskhladze: The Black Sea, Paphlagonia, Pontus and Phrygia in antiquity: aspects of archeology and ancient history. Oxford 2012, p. 191-193.

- ^ Strabo on the Persian Artemis and Mên in Pontus and Lydia. Iulian Moga in Gocha R. Tsetskhladze: The Black Sea, Paphlagonia, Pontus and Phrygia in antiquity: aspects of archeology and ancient history. Oxford 2012, p. 192.

- ↑ Eckhart Olshausen: Gods, heroes and their cults in Pontos - a first report. In: Rise and Fall of the Roman World (ANRW), Part II: Principat , Volume 18, 3. De Gruyter, Berlin, New York 1990, pp. 1870–1871.

- ↑ Eleni Mentesidou: The Terracotta Figurines of Amisos . Dissertation International Hellenic University, Thessaloniki 2015, p. 41; Discussion Portraits and Statues of Mithridates VI. Jakob Munk Højte, in Mithridates VI. and the Pontic Kingdom, Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, p. 145.

- ↑ Eleni Mentesidou: The Terracotta Figurines of Amisos . Dissertation International Hellenic University, Thessaloniki 2015, p. 45.

- ↑ Eleni Mentesidou: The Terracotta Figurines of Amisos . Dissertation International Hellenic University, Thessaloniki 2015, pp. 16-17.

- ↑ Eckhart Olshausen: Gods, heroes and their cults in Pontos - a first report. In: Rise and Fall of the Roman World (ANRW) , Part II: Principat, Volume 18, De Gruyter, Berlin, New York 1990, p. 1869.

- ↑ Eleni Mentesidou: The Terracotta Figurines of Amisos . Dissertation International Hellenic University, Thessaloniki 2015, pp. 41–42.

- ↑ Eleni Mentesidou: The Terracotta Figurines of Amisos . Dissertation International Hellenic University, Thessaloniki 2015, p. 41; Discussion Portraits and Statues of Mithridates VI. Jakob Munk Højte, in Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom, Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, p. 145.

- ^ Characteristics of the Temple States in Pontus. Emine Sökmen, in Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom, Jakob Munk Højte, Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, p. 280.

- ↑ Eckhart Olshausen: Gods, heroes and their cults in Pontos - a first report. In: Rise and Fall of the Roman World (ANRW) , Part II: Principat, Volume 18, Berlin New York, 1990, pp. 1886–1887.

- ^ Characteristics of the Temple States in Pontus. Emine Sökmen, in Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom, Jakob Munk Højte, Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, p. 280.

- ^ Eugene N. Lane : Men: A Neglected Cult of Roman Asia Minor. In: Rise and Decline of the Roman World (ANRW) , Part II: Principat, Volume 18, 3. De Gruyter, Berlin, New York 1990, pp. 2161-2162.

- ↑ Eckhart Olshausen: Gods, heroes and their cults in Pontos - a first report. In: Rise and Fall of the Roman World (ANRW), Part II: Principat , Volume 18, 3. De Gruyter, Berlin, New York 1990, pp. 1887–1888.

- ↑ Eckhart Olshausen: Gods, heroes and their cults in Pontos - a first report. In: Rise and Fall of the Roman World (ANRW), Part II: Principat , Volume 18, 3. De Gruyter, Berlin, New York 1990, p. 1889.

- ↑ Eckhart Olshausen: Gods, heroes and their cults in Pontos - a first report. In: Rise and Fall of the Roman World (ANRW), Part II: Principat , Volume 18, 3. De Gruyter, Berlin, New York 1990, p. 1890.

- ↑ Eckhart Olshausen: Gods, heroes and their cults in Pontos - a first report. In: Rise and Fall of the Roman World (ANRW), Part II: Principat , Volume 18, 3. De Gruyter, Berlin, New York 1990, pp. 1892-1893.

- ^ The Religion and Cults of the Pontic Kingdom: Political Aspects. Sergei Ju. Saprykin, in Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom, Jakob Munk Højte, Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, p. 251.

- ^ The Religion and Cults of the Pontic Kingdom: Political Aspects. Sergei Ju. Saprykin, in Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom, Jakob Munk Højte, Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, p. 253.

- ↑ Apian's Roman History. Translated and annotated by Gustav Zeiß, Leipzig 1837, p. 453.

- ^ The Religion and Cults of the Pontic Kingdom: Political Aspects. Sergei Ju. Saprykin, in Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom, Jakob Munk Højte, Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, p. 256.

- ^ Characteristics of the Temple States in Pontus . Emine Sökmen, in Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom, Jakob Munk Højte, Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, p. 278.

- ^ Characteristics of the Temple States in Pontus . Emine Sökmen, in Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom, Jakob Munk Højte, Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, p. 279.

- ^ Characteristics of the Temple States in Pontus . Emine Sökmen, in Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom, Jakob Munk Højte, Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, p. 280.

- ^ Characteristics of the Temple States in Pontus . Emine Sökmen, in Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom, Jakob Munk Højte, Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, p. 280.

- ^ Characteristics of the Temple States in Pontus . Emine Sökmen, in Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom, Jakob Munk Højte, Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, p. 281.

- ^ Characteristics of the Temple States in Pontus . Emine Sökmen, in Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom, Jakob Munk Højte, Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, p. 282.

- ^ Characteristics of the Temple States in Pontus . Emine Sökmen, in Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom, Jakob Munk Højte, Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, p. 283.

- ^ Characteristics of the Temple States in Pontus . Emine Sökmen, in Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom, Jakob Munk Højte, Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, p. 278.

- ^ The Dynastic History of the Hellenistic Monarchies of Asia Minor According to the Chronography of George Synkellos. Oleg L. Gabelko, in Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom. Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009; Studies in the archeology of hellenistic Pontus: The settlements, monuments, and coinage of Mithradates VI and his predecessors. D. Burcu Arıkan Erciyas, Dissertation, University of Cincinnati, 2001, pp. 78-83; The Kings of Pontus: some problems of identity and date. Brian C. McGing, Rheinisches Museum für Philologie, New Series, 129. Vol., H. 3/4, 1986.

- ↑ FGrH 244, F 82. Retrieved on April 4, 2019 .

- ^ Théodore Reinach: Mithradates Eupator, King of Pontus. Leipzig 1895, p. 22.

- ^ Fritz Geyer : Mithridates 9 . In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume XV, 2, Stuttgart 1932, Col. 2161.

- ↑ François de Callataÿ: The First Royal Coinages of Pontos (from Mithridates III to Mithridates V). In: Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom. Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, pp. 63-94.

- ↑ François de Callataÿ: The First Royal Coinages of Pontos (from Mithridates III to Mithridates V). In: Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom. Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, p. 66.

- ↑ François de Callataÿ: The First Royal Coinages of Pontos (from Mithridates III to Mithridates V). In: Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom. Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, p. 79.

- ^ The Search for Mithridates. Reception of Mithridates VI between the 15th and the 20th Centuries. Lâtife Summerer, in Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom. Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, p. 28.

- ↑ Ergün Lafli, Sami Pataci (ed.): Recent Studies on the Archeology of Anatolia. Oxford 2015, ISBN 978-1-4073-1411-2 , p. 279.

- ^ The Dynastic History of the Hellenistic Monarchies of Asia Minor According to the Chronography of George Synkellos. Oleg L. Gabelko, in Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom. Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, p. 47.

- ↑ a b Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom. Jakob Munk Højte, Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, p. 7.

- ↑ Light Nisa desk and Romanisation in Pontos-Bithynia: An Overview. Christian Marek, in Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom, Jakob Munk Højte, Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, p. 35.

- ^ The Administrative Organization of the Pontic Kingdom. Jakob Munk Højte, in Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom, Aarhus University Press, Århus 2009, p. 100.