Georgios Synkellos

Georgios Synkellos ( Greek Γεώργιος ὁ Σύγκελλος , also George the monk, called Synkellos , Latin Georgius Syncellus ) was a Byzantine monk and historian who lived in the 8th century and died after 810. Georgios lived as a monk in Palestine and later came to the court of the Byzantine patriarch Tarasios , who gave him the office of Synkellos (private secretary of the patriarch). As Synkellos, he had risen to second place in the Byzantine church hierarchy.

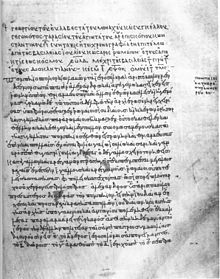

The world chronicle of Georgios

Georgios Synkellos wrote a Christian world chronicle ( Ekloge chronographias ) reaching back into late antiquity , on which he was still working around 810. Since Georgios could not finish the work before his death, the chronicle only deals with the time up to Diocletian (284); but his friend Theophanes continued the work until 813. Recent research suggests that Theophanes 'Chronicle contains much more material from Georgios' preparatory work than previously assumed, but this is controversial.

Georgios, who was very educated and well-read, arranged his portrayal in a rather complex, but also original way, in that he apparently dealt intensively with his templates. He also tried to harmonize contradicting chronologies. The chronicle is therefore more than a mere collection of facts, but tries to organize the narrative. The world chronicle of Georgios stood entirely in the tradition of the Christian chronicles since the 3rd / 4th. Century. The work soon enjoyed a great reputation and was praised for its accuracy and extensive use of sources.

In fact, Georgios relied on numerous older sources, some of which are now lost. For example, he drew on Manetho , Castor of Rhodes , the Chronicle of Dexippos , Sextus Iulius Africanus , Panodorus of Alexandria , Eusebius of Caesarea and numerous other authors. Georgios very often mentions his sources, some of which he questioned and not simply excerpted. The chronicle is valuable in terms of messages from ancient authors that have not been passed down. Also of importance is the chronological order scheme used by Georgios, whereby he dated after the Alexandrian era (calculation of creation to the year 5493 BC). This dating may indicate that the chronicle was written before Georgios left for Constantinople (see below), since this chronology no longer played a major role there.

Anastasius Bibliothecarius used the world chronicle as a source for his Latin chronicle. A largely complete copy of the original Greek text was rediscovered by Isaac Casaubon in a Paris library in 1602 , so that Joseph Justus Scaliger was able to publish a partial edition. A second, complete manuscript was not discovered until the second half of the 17th century.

In older research, Georgios was sometimes seen as a “copyist” who orientated himself almost slavishly on older works (according to Heinrich Gelzer). Several researchers raised legitimate objections to this. The draft of the chronicle and the complex processing of apparently different sources speak against it. Rather, according to many researchers, the chronicle of Georgios represents a masterpiece of Byzantine chronicle and is considered a successful world chronicle. In the more recent research, the quite considerable source value and above all the quality of the presentation and its range, unsurpassed in Byzantine chronicles, is emphasized.

It is partly assumed that Georgios had already largely completed the Chronicle when he set out for Constantinople. With this in mind, considerations have been expressed that, since Greek scholarship was still very much alive in the Syrian region, this influenced the writing of the work. In the material for the period after 284, which Georgios brought with him (and which he then gave Theophanes, who was less well-read than Georgios), an Eastern chronicle was probably already incorporated. Today this is mostly identified with the lost chronicle of Theophilos of Edessa .

Editions and translations

- Wilhelm Dindorf (Ed.): Georgius Syncellus et Nicephorus Cp. (= Corpus Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae . Volume 22/23). 2 volumes, Weber, Bonn 1829 (digital copies: volume 1 , volume 2. Text passages from the Synkellos chronicle are sometimes given to this day using the page number in Dindorf).

- Alden A. Mosshammer (Ed.): Georgii Syncelli Ecloga chronographica . Teubner, Leipzig 1984 (today authoritative critical edition).

- William Adler, Paul Tuffin (transl.): The Chronography of George Synkellos. A Byzantine Chronicle of Universal History from the Creation . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2002 (English translation with extensive introduction and commentary; review ).

literature

- Heinrich Gelzer: Sextus Julius Africanus and the Byzantine chronography . 2 vols. Leipzig 1885–1898 (reprint: Gerstenberg, Hildesheim 1978, ISBN 3806707480 ).

- William Adler: Time immemorial: archaic history and its sources in Christian chronography from Julius Africanus to George Syncellus . Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. Washington / DC 1989.

- Warren Treadgold : The Middle Byzantine Historians . Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2013, p. 38ff.

Web links

- Entry in the Catholic Encyclopedia , Robert Appleton Company, New York 1913.

Remarks

- ↑ See The Chronicle of Theophanes Confessor. Byzantine and Near Eastern history AD 284-813. Translated and commented by Cyril Mango and Roger Scott, Oxford 1997. S. LII ff.

- ^ Adler / Tuffin, The Chronography of George Synkellos , pp. LX ff.

- ↑ See Adler / Tuffin, The Chronography of George Synkellos , pp. LXXVIII ff.

- ↑ Cf. Wolfram Brandes: Early Islam in Byzantine Historiography. Notes on the source problem of the Chronographia des Theophanes . In: A. Goltz / H. Leppin / H. Schlange-Schöningen (eds.): Beyond the borders . Berlin / New York 2009, pp. 313–343, here pp. 331ff.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Georgios Synkellos |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | George the monk, called Synkellos; Georgios ho Synkellos; Georgius Syncellus |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Byzantine monk and historian |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 8th century |

| DATE OF DEATH | after 810 |