Cappadocia

Cappadocia ( Turkish Kapadokya , Greek Καππαδοκία , German also Cappadocia ) is a landscape in Central Anatolia in Turkey .

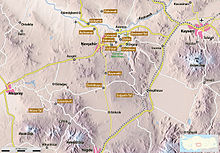

The area known as Cappadocia now mainly includes the provinces of Nevşehir , Niğde , Aksaray , Kırşehir, and Kayseri . One of the most famous places is Göreme with its out of the soft tufa hewn cave architecture . Göreme is considered the center of Cappadocia, the unique complex of rock formations located there was included in the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1985 as a mixed cultural and natural heritage site " National Park Göreme and the rock structures of Cappadocia " . Another special feature is a multitude of underground cities , the most famous of which are Kaymaklı and Derinkuyu , which have been unearthed by archaeologists since the 1960s. Other well-known cities are Urgup and Avanos .

Surname

The name Cappadocia comes from the old Persian katpatuka . The meaning of the word is controversial. Some of the researchers assume the importance of the land of beautiful horses , which would agree with the fact that ancient sources boast Cappadocia for its horse breeding. Others consider the name to be an Iranian form of the Hittite Kizzuwatna .

geology

The UNESCO World Cultural and Natural Heritage Göreme-Cappadocia is located in the center of an area of formerly intense volcanic activity, which decisively shaped the landscape today. In the course of the Alpid orogeny , the area of Anatolia was also unfolded over the last 100 million years, which was determined by large lake plateaus and tropical marshland. As the Taurus Mountains rose further to the south, large amounts of lava were slowly pushed to the surface of the earth in the interior of Anatolia, which ultimately led to the formation of the volcanic landscape of Cappadocia.

In the vicinity of the volcanoes Erciyes Dağı ( 3917 m ), Hasan Dağı and the Melendiz mountain ranges between the Turkish cities of Kayseri , Aksaray and Niğde , there have been significant eruptions, especially since the Neogene , i.e. in relatively recent geological times, as well as lava Hurled large amounts of volcanic ash into an area of around 10,000 km², which today is geologically commonly referred to as the clearing landscape of Cappadocia (Persch, 1935). The landscape of Central Anatolia was completely re-shaped by newly formed volcanic mountains and layers of volcanic tuff that filled the deeper swamp and lake plateaus.

Over the centuries, these layers of volcanic tuff, formed by irregular eruptions, condensed into a relatively solid rock that, depending on the location and the eruption horizon, has been eroded extremely quickly to this day . In the further alternation between eruption and rest periods, the volcanoes continued to grow. In the transition period between the Pliocene and the Pleistocene , the most violent eruptions occurred, which played a key role in shaping today's regional landscape. The volcanic activities continued into historical times and were also depicted in Stone Age wall paintings in the ancient settlement of Çatalhöyük (approx. 8000 BC ) south of Konya (outside Cappadocia) . Until the century before last, reports of active fumaroles and columns of smoke from the Erciyes Dağı region near Kayseri , although these have currently come to a standstill.

As a result of volcanic eruptions, the former lake area around Ürgüp and in the valley landscapes of the later river Kızılırmak expanded further. This led to sediment deposits of earth and clays, which later became particularly important for the pottery town of Avanos.

erosion

The rest of the inland lakes were drained over a large area due to earth shifts in Central Anatolia, elevations on the one hand and deepening of the riverbeds on the other, which led to strong erosion that continues to this day , which significantly shapes the geomorphological picture of the tuff landscape of Cappadocia. As a result, aeolian, fluviative, atmospheric and thermoclastic erosion activities created the bizarre and unique shape of the landscape.

This rapid process of erosion shows how young and unbalanced the geological conditions in the area of Cappadocia are. As before, considerable amounts of tuff are cleared and after every heavy downpour one can sense the enormous erosion forces in the valleys, which form new, decimeter-thick structures and wash away large amounts of erosion material.

In the lower slopes, special structures sometimes develop due to erosion: the tuff towers of the fairy chimneys (Turkish peri bacalari , English fairy chimneys ), which are famous for Cappadocia , which are protected for a certain time by harder, overlying layers of volcanic tuff. Only after the protective cover has slipped off, the effects of wind and weather, birds and insects - (and today also tourists and air pollution ) - intensify the erosion, which destroys the cones relatively quickly.

Not to be forgotten is the activity of the local population, who over the millennia has hollowed out many of the tuff formations for residential purposes and for churches as well as for dovecotes , which often reach the highest peaks of the tuff cones.

On the one hand, this form of architecture is an example of particularly creative and ecologically and economically sensible living and working. On the other hand, because erosion is accelerated by often careless excavation, a ban on further excavation was pronounced within the scope of registering the area of Cappadocia as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, but this is often not complied with.

View over Goreme

Ihlara valley near Aksaray

Castle Rock of Uçhisar

history

The area was settled around 8000–7500 BC. BC, parallel to the southern settlement area around Konya. The earliest traces of settlers date from around 6500 BC. The Hittites also made the fertile soil for themselves as early as 1600 BC. BC to use and cultivated grain. Later came the Phrygians and Lydians , then in the late 7th century BC. The Medes , which were soon replaced by the Persians . After the Alexander campaign , which had only briefly touched on Cappadocia, which the previous Persian satrap Ariarathes I used to secure his own rule, Cappadocia fell to the Macedonians. Perdiccas defeated Ariarathes I in 323 BC. And appointed Eumenes of Cardia as the new satrap. Ariarathes I was executed, but his son Ariarathes II is said to have fled to Armenia with some of his followers (Diod. 31, 19, 4-5).

Soon, however, the Diadochi fought and Cappadocia also got into these power struggles. First of all, Eumenes and Krateros faced each other in the first Diadoch War . Eumenes won the battle, and Krateros fell. But since Perdiccas had fallen in Egypt, the Macedonian army assembly sentenced Eumenes to death. Antigonus I. Monophthalmos received the supreme command of the troops that were supposed to defeat Eumenes, the satrapy of Cappadocia went to Nikanor , who, however, soon appears in the historical accounts as General of Antigonos and thus seems to have handed over the satrapy to him (either around 319 BC) . Or at the latest 312 BC). Eumenes was able to assert himself for some time, but finally had to be in the spring of 319 BC. Flee to media.

In the second coalition war 316 / 315-311 BC BC Antigonus was able to maintain his rule over Asia Minor and thus also over Cappadocia.

After Diodorus, Ariarathes II was able to return to Cappadocia while Antigonus was still alive, where he defeated his strategist Amyntas. In the meantime, Mithridates I had created his own sphere of power in northern Cappadocia , the later kingdom of Pontus .

After the Battle of Ipsos in 301 BC. BC, in which Antigonus fell, power over Asia Minor was re-regulated by the Diadochi. Lysimachus officially received Asia Minor up to Taurus, but the ancient authors contradict each other on this point. In contrast to Diodorus , Appian claims that after this battle Cappadocia went directly to Seleucus I Nicator ( Syriake 55 [281]).

However, no later than after the Battle of Kurupedion in February 281 BC. Seleucus was able to claim Asia Minor and thus Cappadocia for himself.

The Seleucid claim to rule over Cappadocia was fought by the Ariarathids and from around 260 (or earlier) this dynasty was able to break away from the Seleucids, Cappadocia became an independent kingdom under Ariarathes I and began its own coinage. Tetradrachms (worth four drachms), drachmas and bronze coins were minted, later under the Ariobarzanids only drachmas in large volumes were minted. The back of the tetradrachms and drachms show the standing Athena Nikephoros , as well as numerals, which are probably dating. Initially closely linked to the Seleucid House, the orientation of the Ariarathids changed from 188 BC onwards. The crushing defeat that Antiochus III. had suffered against the Romans , the balance of power in Asia Minor shifted again. From then on, Pergamon , the Roman ally, dominated politics and the Ariarathids combined with the Pergamene Attalids . In addition, the Ariarathids got into a conflict with the Pontic Mithridatids, which would culminate in the Mithridatic Wars after the dynasty died out .

Also the Ariobarzanids from 95–36 BC. BC Cappadocia ruled, had with the Pontic king Mithridates VI. Eupator a great opponent and protracted battles for rule. Above all, the Roman generals Sulla , Lucullus and Pompeius were important "allies" for the Ariobarzanids.

Since the first king Ariarathes I (333-322 BC) coins were minted in Cappadocia for all kings up to Archelaus (36 BC -17 AD) (see Simonetta). In addition to the coins of kings, autonomous coins were also minted. Since the takeover of Cappadocia by the Romans, coins were minted in the Roman province of Cappadocia, beginning with the emperor Tiberius (14 AD) and ending with Gordian III (244 AD). The extinct Vukan Erciyes Daği is the sacred mountain Argaios of antiquity and can be admired on many of the reverse sides of Cappadocia coins. (see Ganschow)

Mark Antony set 36 BC. Chr. Archelaos as the new king of Cappadocia, who brought back after the wars with Mithridates and the following difficult years of stability and prosperity. Emperor Tiberius put an end to the independent kingdom in 18 AD and integrated it as the imperial province of Cappadocia . The city of Eusebia became the capital of the new province under the new name of Caesarea .

Known governors:

- Cn. Pompeius Collega, in the years 75/76, proven by Stumpf p. 217

- M. Hirrius Fronto Neratius Pansa, in the years 77/78 to 79/80, proven Stumpf p. 222

under Titus , evidenced by an inscription from Komana .

- A. Caesennius Gallus, in the years 80/81 to 82/83, proven by Stumpf p. 225

- Ti. Iulius Candidus Marius Celsus or L. Antistius Rusticus in the years 91/92 or 92/93, proven by Stumpf p. 238

- T. Pomponius Bassus mid-94 to mid-100, proven Stumpf p. 258

- Q. Orfitasius Aufidius Umber, in the years 100/101 to 103/104, proven Stumpf p. 281

- P. Calvisius Ruso Iulius Frontinus, in the years 104/105 to 106/107, proven Stumpf p. 283

- M. Junius Homullus, in the years 112/113 to 113/114, proven by Stumpf p. 285

- L. Catilius Severus, in the years 114/115 to 116/117, proven Stumpf p. 286

- (L. Stratorius?) Secundus, in the years 126 to 128, proven by Stumpf p. 289

- Lucius Catilius Severus between 111 and 117

- M. Munatius Sulla Cerialis under Elagabal

- M. Ulpius Ofellius Theodorus under Elagabal

- Q. Aradius Rufinus (?) Approx. 222–226

- Asinius Lepidus 226

- Q. Iulius Proculeianus, 231 under Severus Alexander , evidenced by a milestone from Sebastopolis

- Aradius Paternus, 231 under Severus Alexander, evidenced by a milestone from Podandus .

Under Valens , the province was divided in 372. Caesarea remained the capital of the northern part (Prima), Podandus became that of Cappadocia secunda in the south, but it was soon replaced by Tyana .

After the division of the empire in AD 395, Cappadocia became an Eastern Roman province ( Cappadocia (Byzantine theme) ). The Isaurians invaded Cappadocia in the 5th century AD, the Huns in the 6th century. Chosrau I invaded Anatolia in 579 and set fire to Sebastea in Cappadocia . The Byzantine army was defeated by the Seljuks in 1071. The Turkmen followed, and finally the Ottomans . Greeks have lived in the area since ancient times. However, the Christian population, although largely speaking Turkish in everyday life, was forcibly relocated to Greece in the early 1920s. The Greek dialect of this region, Cappadocian , is now considered extinct.

Religion and culture

From early Christianity to the 20th century, Caesarea Cappadociae (now Kayseri) was an important bishopric of the Patriarchate of Constantinople . In church history , the three Cappadocians are known who came from this area and lived mainly there. Cappadocia was one of the most important early Christian centers. Until 1071 it was under Byzantine rule. More than 3000 churches, which have been uncovered to this day or even built as new buildings in the “long 19th century”, bear witness to a Christian past that reached into the beginning of the 20th century. Cappadocia was spared the horrors of World War I and the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922). The still stately congregations of Greek Orthodox Christians left the region after the Treaty of Lausanne 1923/24 as part of the large population exchange between Turkey and Greece .

Cappadocia was on the famous Silk Road . The people living there were often attacked by many different aggressors. But that is not the only reason why the residents have hollowed out the soft tuff to create living space for themselves. Entire subterranean cities emerged that can still be seen today.

Because of this lively cultural history and the sheer breathtaking landscape formations, the region was placed under protection by UNESCO in 1985 as a World Heritage Site and World Natural Heritage Site . More recently, the Christian buildings of the Ottoman period have also received monument preservation and tourist attention, occasionally, if they have not been converted into mosques, with special permission for Christian liturgical use.

Ürgüp (Prokopi), Johannes von Euböa church, 1834 or 1868, destroyed around 1950, historical photograph (1914).

Derinkuyu (Malakopi), Theodoroi Church, consecrated in 1858.

literature

- Kappadocia - periēgēsē stē Christianikē Anatolē. Phōtogr .: Liza Ebert ... .Ekd. Adam, Athēna 1991, 258 pp.: Numerous. Ill. ISBN 960-7188-00-4 .

- Neslihan Asutay-Fleissig: Templon systems in the cave churches of Cappadocia . Frankfurt am Main 1996, ISBN 3-631-49656-7 .

- Roberto Bixio (Ed.): Cappadocia - le città sotterranee. Rome 2002, ISBN 88-240-3523-X .

- Andus Emge: Living in the Goreme Caves. Traditional construction and symbolism in Central Anatolia. Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-496-00487-8 .

- Thomas Ganschow, Coins of Cappadocia - Henseler Collection - Volume I Kingdom and Kaisareia up to 192 AD ( ISBN 978-605-396-466-7 ) and Volume II Kaisareia from 193 AD

Chr., Tyana and Hierapolis on Saros ( ISBN 978-605-396-465-0 ), Istanbul 2018

- Michael Henke: Cappadocia in Hellenistic times. Münster 2005, ISBN 3-640-66760-3 .

- Friedrich Hild , Marcell Restle : Cappadocia (Kappadocia, Charsianon, Sebasteia and Lykandos). Tabula Imperii Byzantini . Vienna 1981, ISBN 3-7001-0401-4 .

- Catherine Jolivet-Lévy: Les églises byzantines de Cappadoce. The program iconographique de l'abside et de ses abords. Paris 1991, ISBN 2-222-04451-0 .

- Catherine Jolivet-Lévy: La Cappadoce. Mémoire de Byzance. Paris 1997, ISBN 2-84272-021-0 , ISBN 2-271-05500-8 .

- Catherine Jolivet-Lévy: La Cappadoce médiévale. St.-Léger-Vauban 2001, ISBN 2-7369-0276-9 .

- Catherine Jolivet-Lévy: Etudes cappadociennes. Pindar Press, London 2002, ISBN 1-899828-48-6 .

- Brigitte LeGuen-Pollet (ed.): La Cappadoce méridionale jusqu'à la fin de l'époque romaine, Ètat des recherches; actes du colloque d'Istanbul. Institut Français d'Etudes Anatoliennes, 13. – 14. avril 1987. Paris 1991, ISBN 2-86538-225-7 .

- Lyn Rodley: Cave monasteries of Byzantine Cappadocia. Cambridge 1985, ISBN 0-521-26798-6 .

- Alberto M. Simonetta, The Coinage of the Cappadocian Kings: A revision and a catalog of the Simonetta Collection, in: Parthica 9, 2007 (Pisa - Roma 2008), 9-152.

- Gerd R. Stumpf, Numismatic studies on the chronology of the Roman governors in Asia Minor (122 BC - 163 AD) (Saarbrücken 1991).

- Nicole Thierry: Haut moyen-age en cappadoce. Les églises de la region de Çavusin. Bibliothèque archéologique et historique. Vol. 102 (2 vol.). Paris 1983, 1994.

- Nicole Thierry: La Cappadoce de l'antiquité au Moyen Age. Bibliothèque de l'antiquité tardive. Vol. 4. Turnhout 2002, ISBN 2-503-50947-9 .

- Rainer Warland : Byzantine Cappadocia. Zabern, Darmstadt 2013, ISBN 978-3-8053-4580-4 .

- Hanna Wiemer-Enis: Late Byzantine wall painting in the cave churches of Cappadocia in Turkey. Petersberg 2000, ISBN 3-932526-70-8 .

- Catalog "Discover Erciyes" of the ski area of the same name, 2015

Movie

- Göreme - home in the caves . Documentation, 45 minutes. Film by Andus Emge & Shahid Sheikh, Production: SWF III Baden-Baden, Countries - People - Adventure , 1991. Synopsis of ARD .

- Wonderful world of Turkey - a journey through Cappadocia . Documentation, 45 minutes. Film by Ingeborg Koch-Haag, production: Saarländischer Rundfunk , first broadcast: October 24, 2007. Summary of the NDR .

See also

Web links

Research society

- Pan-Hellenic Union of Cappadocian Societies webpage (umbrella organization)

Others

- Detailed Cappadocia map with hiking trails and landmarks

- Website of the 'Cappadocia Academy' with lots of information about the region

- History of the Greeks from Cappadocia (English)

- Images of cave churches in Cappadocia

- Aude Aylin de Tapia. La Cappadoce chrétienne ottoman: un patrimoine (volontairement) oublié? . In: European Journal of Turkish Studies [online , 20. 2015]

- Ermeni ve Rum kältür varlklaryla Kayseri = Kayseri with its Armenian and Greek cultural heritage. Ed. Altug Ylmaz. Hrant Dink Vakf Yaynlar, Istanbul 2016. 261 pages (numerous photos), ISBN 605-66011-4-5 ; ISBN 978-605-66011-4-9 ; Text in Turkish and English.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Daredjan Kacharava, Murielle Faudot, Evelyne Geny: Pont-Euxin Et Polis: Polis Hellenis Et Polis Barbaron. Actes Du Xe Symposium de Vani, 23–26 September 2002: Homage to Otar Lordkipanidzé Et Pierre Lévêque . Presses Univ. Franche-Comté, 2005, ISBN 2-84867-106-8 , pp. 135 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Archived copy ( Memento of the original from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Rebecca Turner: Late Quaternary fire histories in the eastern Mediterranean region from lake sedimentary micro-charcoals. ( Memento of the original from April 7, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Thesis for doctor of philosophy. 2007, p. 74.

- ↑ Szaivert / Sear, Greek coin catalog, Volume 2, Munich 1983, pages 374-378

- ↑ Mittag, Greek Numismatics - An Introduction, Heidelberg 2016, pages 192 - 193

- ↑ CIL III, p. 2063.

- ^ RP Harper: Roman Senators in Cappadocia . In: Anatolian Studies . 14, 1964, p. 166.

- ^ RP Harper: Roman Senators in Cappadocia . In: Anatolian Studies. 14, 1964, p. 165.

- ↑ Clive Foss: The Persians in Asia Minor and the End of Antiquity. In: The English Historical Review 90 , No. 357, 1975, 722.

- ↑ Sacit Pekak: Kappadokya'da Post-Bizans Dönemi Dini Mimarısı. In: METU Journal of the Faculty of Architecture 26.2 (2009) 249-277.

Coordinates: 38 ° 40 ′ 14 " N , 34 ° 50 ′ 21" E