Derinkuyu underground city

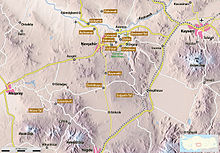

Derinkuyu ( Turkish for deep well / shaft , former name Malakopía ) is next to Kaymaklı the most famous of the underground cities in Cappadocia and is located in the place of the same name . This is located in the Turkish province of Nevşehir, 29 kilometers south of the provincial capital . In addition to Derinkuyu, more than 50 underground cities are suspected in Cappadocia; 36 have been discovered so far, but very few have been made available to the public. Derinkuyu is the largest accessible facility. The origin of these cities and also Derinkuyus is controversial. Some archaeologists see the builders in the Hittites over 4000 years ago. Others suspect that Christians built the cities to protect them from persecutors. It is certain that it was only the Christian residents between the 6th and 10th centuries that gave the complex its present-day form.

description

The tunnel system was discovered by accident in 1963. Since then, eight floors have been uncovered, the uncovered rooms have a total area of 2500 square meters. The facility was opened to the public as early as 1965; the deepest accessible point is 55 meters below the surface. It is estimated that only a quarter of the original site has been exposed.

The upper floors were mainly set up as living rooms and bedrooms, but they also housed a wine press and a monastery complex. Pets were also kept underground. The lower floors contained meeting and storage rooms as well as a dungeon . Several rooms on different floors were most likely used as churches, including the so-called "clover-leaf church" on the seventh floor, which is laid out in the shape of a cross. It has a length of 25, a width of ten and a height of three meters. The estimates of the number of residents are contradicting and vary between 3,000 and 50,000. It is believed that Derinkuyu was connected to the underground city in the neighboring village of Kaymaklı by a nine-kilometer tunnel.

The underground city could be sealed off by the so-called “rolling stone doors” that look like millstones . In the event of danger, these were rolled in front of the entrance from the inside and presented an obstacle that was difficult to overcome from the outside. Communication with the outside world could be maintained at such times via shafts that led from the first two floors to the outside. These were three to four meters long and ten centimeters in diameter.

Ventilation system

The ventilation system is extremely complex and sophisticated. A total of over 15,000 shafts are said to have led upwards from the first underground level. There are fewer on the lower floors, but air circulation still works today down to the eighth floor. The ventilation system with its 70 to 85 meter deep shafts also served to transport water. Until shortly before the discovery, the population of Derinkuyu drew their water from these wells without knowing the associated cave system. The name of the place is derived from this, because derin kuyu means “deep well” or “shaft” in Turkish .

Reasons for building underground cities

The most common theory to motivate the construction of underground cities in Cappadocia is the assumption of a need for protection. For example, the Christians are said to have sought refuge from the invading Seljuks and used the underground cities as a well-camouflaged refuge . This is also indicated by the locking stones, which can hardly be opened from the outside.

Far less spectacular is the assumption that the cities were built to protect against the extreme climatic conditions of the region, because the winters are cold and snowy, the summers are hot and dry. According to this theory, the underground facilities made it possible to store agricultural yields at a constant temperature and protected from moisture and thieves.

See also

literature

- Ömer Demir: Cappadocia: cradle of history . Extended 3rd edition. Ajans-Türk Publ. & Printing, Ankara 1988

- Michael Bussmann, Gabrielle Tröger: Turkish Riviera, Cappadocia . Michael Müller Verlag, Erlangen 2003, ISBN 3-89953-108-6

- Wolfgang Dorn: Turkey - Central Anatolia: between Phrygia, Ankara and Cappadocia . DuMont, 2006, ISBN 3770166167 ( on GoogleBooks )

- Peter Daners, Volker Ohl: Cappadocia. Dumont, 1996, ISBN 3-7701-3256-4

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Ömer Demir: Cappadocia: cradle of history . Pages 8–21, see literature

- ^ Index Anatolicus Malakopía

- ^ Bussmann, Tröger: Turkish Riviera, Cappadocia . Page 232ff, see literature

- ↑ Florian Harms: In the realm of raw people . Spiegel Online, April 2008

Web links

- www.twine.com: Derinkuyu, the mysterious underground city of Turkey

- Liese Knorr: The Underground Cities in Turkey , 1992

- Thomas Krassmann: Underground Cities in Cappadocia - Myth and Reality (PDF; 587 kB)

Coordinates: 38 ° 22 ′ 53 ″ N , 34 ° 44 ′ 10 ″ E