Cave architecture in Cappadocia

The cave architecture in Cappadocia in central Turkey includes living rooms and utility rooms as well as sacred buildings such as churches and monasteries, which were carved out of the soft tuff of the landscape.

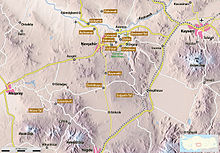

The Erciyes Dağı volcanoes south of Kayseri , Hasan Dağı south-east of Aksaray , Melendiz Dağı near Niğde and some smaller volcanoes covered the Cappadocia region with a layer of tufa for 20 million years until prehistoric times , from which the well-known rock formations of the area formed through erosion . The process is a special form of groove erosion , which is widespread throughout Turkey , whereby the stability of the volcanic tuffs and ignimbrites creates particularly deep and steep-walled grooves, which then form the tower-like shapes through lateral intersection. Since this soft rock is relatively easy to work with, it was probably already formed into caves by humans in the early Bronze Age , which over the years were expanded into extensive residential and monastery complexes and entire cities. The Cappadocia region belongs since 1985 to the World Heritage of UNESCO .

Prehistory and early history

Traces of settlement show that the area of Cappadocia was already inhabited in prehistoric times. It is not known whether caves were built during this time. However, it is likely that at least in the Bronze Age, when the region belonged to the core area of the Hittite Empire, the first passages and rooms were dug into the rock as deposits and possibly also as a retreat. A hand tool of Hittite origin was found in the underground city of Derinkuyu , but it could also have got there at a later time. The earliest mention is in the anabasis of Xenophon , he speaks of people in Anatolia who built their houses underground.

“The houses were underground, at the entrance (narrow) like a well hole, but wide below. The entrances for the cattle were dug, but the people climbed down on ladders. Goats, sheep, cattle and poultry were found in the apartments, along with their young. "

Christian settlement

The beginning Christian settlement of the region took place in the first century AD by hermits, who withdrew from the Christianized area around Caesarea into the solitude of the tuff landscape. They either settled in existing caves or dug their own dwellings in the rocks. Since they were looking for solitude rather than protection from enemies, their rooms remained largely on the surface of the earth. When the Christian church reorganized itself in the 4th century under the church fathers Basil of Caesarea , Gregory of Nyssa and Gregor of Nazianz , they were followed by ever larger Christian groups over the next few centuries, who settled here and formed monastic communities and accordingly more and needed larger living and church rooms. After the Isaurians , in the 5th century the Huns and finally in the 6th century Persian groups invaded Cappadocia and the latter conquered Caesarea in 605, the intensive construction of underground and above-ground cave structures and entire cities began. Now the structures were built mainly under security and defense aspects. After Arabs increasingly invaded the region from 642 onwards , these aspects became increasingly important, so that for three centuries Christian communities lived here hidden and protected against attackers. During the period of Byzantine rule that followed, Christianity, and with it Christian architecture, flourished in Cappadocia. By the 11th century, around 3000 churches were carved out of the stone.

After the Seljuks - Sultan Alp Arslan defeated the Byzantine Emperor Romanos IV in the Battle of Manzikert in 1071 and thus ushered in the end of the Byzantine Empire and the beginning of Turkish domination in Anatolia, this marked the beginning of decline, despite the religious tolerance of the Seljuks of Christianity in Cappadocia and with it the slow decline of church architecture. After the gradual emigration of the Christian residents, the existing monastery rooms were taken over by Turkish farmers who converted them according to their needs. Since camouflage and defense were no longer necessary, facades and houses were built in front of the formerly hidden, inconspicuous caves, which included the underground rooms.

The cave rooms were used by the Turkish residents until the 20th century, also because of the consistently pleasant temperatures. As late as 1838, the inhabitants of the underground cities were still sheltering from Egyptian troops. The last remaining Christians left the area in 1923 as part of the Greek-Turkish population exchange . The last Turkish residents moved out of the Zelve cave settlement in the 1950s after earthquakes caused more and more damage and the use of it became increasingly dangerous. Until today, however, z. B. in Uçhisar , in Ortahisar or in the Soğanlı valley , individual caves, which are mostly in connection with front or attached houses, at least in summer still used as living rooms because of the pleasant temperatures.

Underground cities

Underground cities were well suited for defense and protection from attackers. The few entrances were camouflaged by bushes and thus hardly recognizable from the outside. Inside, they consisted of a labyrinth of corridors that was unmanageable for outsiders, each of which could be closed off individually by meter-high, millstone-like stones. The stones were installed in such a way that they could be rolled into the locked position relatively easily from the inside, but could not be moved from the outside. They had a hole in the middle that probably served as a kind of peephole . In some cities there are holes in the ceiling above through which enemies could be attacked with spears. The cities went over 100 m deep into the earth with up to twelve floors (found to this day) and had everything to show that was necessary for a long-term stay. Most of the upper floors housed stables and storage rooms, which had a constant temperature of around ten degrees Celsius. Containers for various types of food were incorporated into the rock walls, as well as hollows for vessels in which, for example, liquids could be stored. Further down there are living and utility rooms, with furniture such as benches, tables and sleeping quarters being carved into the stone. The economic areas include, for example, a wine press in Derinkuyu , a melting pot for copper in Kaymaklı , but also cisterns and wells that ensure the supply of drinking water for longer stays. There was also a dungeon and toilets.

There are also monastery rooms and churches on the lower floors. The churches in the underground cities are rather simple and have little or no decoration. They usually have a cruciform floor plan, sometimes with one or two apses . Paintings as in the later, larger churches, z. B. in Göreme , are not to be found here. In the adjoining rooms of the churches, tombs are carved into the walls . In order to supply those trapped there for up to six months in the event of a defense with fresh air for breathing, firing and lighting, a complex system of air shafts that still works today was in place. It also served as an outlet for the smoke from the fireplaces in the kitchen rooms.

Almost 40 underground cities are known throughout Cappadocia, but only a small part of them have been made accessible to the public. Other previously undiscovered cities are suspected. Originally they are said to have been connected to each other by corridors that are kilometers long, but none of these corridors has yet been proven. The estimates of the population of the cities diverge strongly and are between 3,000 and 30,000. The largest is probably the still largely unexplored Özkonak ten kilometers northwest of Avanos with an assumed 19 floors and 60,000 inhabitants, the best known and best developed for tourism are Derinkuyu and Kaymakli.

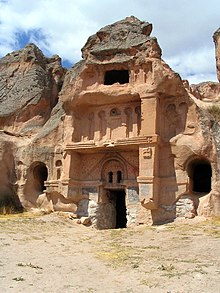

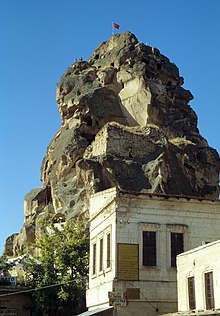

Cities and castles

A counterpart to the underground cities are the so-called castles or castle mountains, for example from Uçhisar or Ortahisar . These are 60 or 90 m high rocks, which are also criss-crossed by a tangle of corridors and rooms. Due to demolitions as a result of erosion and earthquakes, parts of it are now exposed. They also served as places of retreat in the event of danger and could be sealed off with locking stones of the same type as in the underground cities. They offered shelter to around 1,000 people. The ground-level caves have now been partially integrated into the front of the houses and still serve as stables and, above all, storage rooms.

There are also a number of places that consist of collections of apartments and other rooms carved into rock walls. The largest of these is Zelve , the most famous Göreme , but also in the Soğanlı Valley , in Gülşehir or Güzelyurt , entire cities made of rock can be seen. Here, distributed over one or more valleys, underground buildings mix with residential and monastery complexes carved into steep walls, utility rooms of all kinds and churches. These are equipped with more decorations and paintings than in the underground cities.

Here, too, a large part of the rooms is connected via a branched tunnel system. The entrances are mostly open because the main focus was not so much on the defense aspect as with the underground cities. Nevertheless, the entry is sometimes very difficult due to the fact that vertical rock faces have to be climbed using simple grip and step recesses. Even with the inner tunnel system, the paths through steep, narrow corridors and vertical chimneys are quite difficult. In many of these places, pigeon houses are also carved into the stone in high cliffs , the entry holes of which are often painted in color. The painting is intended to attract the birds, which then set up their nesting sites and thus provide the coveted bird droppings. This is taken out once a year in difficult climbing maneuvers and used as fertilizer. Existing caves were also converted into pigeon houses by hammering in nesting niches and walling up the entrances.

Churches

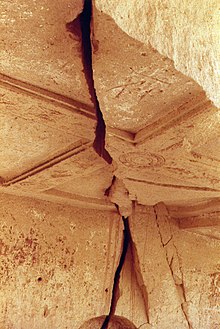

The countless churches in the Cappadocia region range from the simplest, completely unadorned rooms in the underground cities, which can only be identified as sacred rooms by an altar stone , to cross-domed churches and three-aisled basilica . They are all based strongly on the well-known Byzantine sacred architecture. They usually have a cross-shaped floor plan, one or more domes, barrel vaults or combinations of all these elements. The common difference to built church architecture is that the builders were not bound by static laws, they did not have to plan any load-bearing walls or pillars, as they only removed the spaces to be created from the existing rock - ex negativo. Nevertheless, elements such as columns or pilasters that have been adopted from classical building architecture can also be found, but they have no supporting function. The furnishings of the churches such as altars, benches, baptismal fonts, choir stalls and choir screens are in most cases also made from the stone. From the outside they are often visible from a distance through their representative facades with blind arches , gables and columns.

To a certain extent, the time the churches were built can be read from the design of the paintings. While the simple church rooms in the underground cities are without any painting, the first churches built above ground still show simple figural frescoes . An example of this is the Ağaçaltı Kilesesi in the Ihlara Valley , it was probably built in the seventh century. Later churches only have simple geometric ornaments such as crosses, zigzag lines, diamonds or rosettes, which are applied to the rock with red paint. These date back to the eighth and early ninth century, from the period of Byzantine iconoclasm ( iconoclasm ). Possibly under Arab-Islamic influence were under Emperor Leo III. all depictions of Jesus, the apostles and saints are forbidden as sin. In the two-story St. John's Church in Gülşehir , the iconoclastic patterns can still be seen on the lower floor.

In the ninth century, the iconoclasm ended, and the buildings that were built from then on were decorated with ever more splendid frescoes. Most of the older churches were also painted over, so that only relatively little of the old painting has survived. In some churches that have not been restored, the old geometric patterns can be seen under the crumbling plaster. The more detailed the paintings are, the younger they can be assessed. It is assumed that there were collections of templates for the artists, with the help of which the outlines of the paintings were sketched and then colored in. Most common were scenes from the life of Jesus such as B. Birth, baptism by John , the miracles , the betrayal by Judas , denial by Peter , the Lord's Supper , crucifixion , burial and resurrection .

Many of the frescoes are badly affected by stones being thrown, mainly around the eyes. However, these are the consequences of later Islamic iconoclasm . Various churches have been extensively restored since the 1980s.

Older painting in St. John's Church in Gülşehir

Research history

The first descriptions of the Cappadocian caves date back to 402 BC. From the anabasis of the Xenophon . In the 13th century AD, the Byzantine writer Theodoros Skutariotes reports on the favorable temperature conditions in the tuff caves, which turn out to be relatively warm in the cold Anatolian winters and pleasantly cool in the hot summer months. In 1906 the German researcher Hans Rott traveled to the Cappadocian landscape and reported about it in his book Asia Minor Monuments . Also at the beginning of the last century Guillaume de Jerphanion visited the region and wrote the first scientific paper on the cave churches and especially the paintings. Systematic research into architecture did not begin until the 1960s, when the last residents had left the rock dwellings. Marcell Restle conducted research on site in the 1960s and published extensive studies on the architecture of the stone-built churches and the painting of the cave churches. The Englishwoman Lyn Rodley examined the monastery complex in the 1980s. In the 1990s, the German ethnologist Andus Emge worked on the change in traditional cave dwelling in the Cappadocian town of Göreme.

See also

literature

- Peter Daners, Volker Ohl: Cappadocia . Dumont, Cologne 1996, ISBN 3-7701-3256-4

- Andus Emge: Living in the Goreme Caves. Traditional construction and symbolism in Central Anatolia. Berlin 1990. ISBN 3-496-00487-8

- John Freely : Turkey . Prestel-Verlag, 2nd edition, Munich 1986, ISBN 3-7913-0788-6

- Marcell Restle: Studies on the early Byzantine architecture of Cappadocia . Publishing house of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, 1979, ISBN 3700102933

- Friedrich Hild , Marcell Restle : Cappadocia (Kappadocia, Charsianon, Sebasteia and Lykandos). Tabula Imperii Byzantini . Vienna 1981. ISBN 3-7001-0401-4 .

- Marianne Mehling (Hrsg.): Knaur's cultural guide in color Turkey . Droemer-Knaur, 1987, ISBN 3-426-26293-2

- Lyn Rodley: Cave Monasteries of Byzantine Cappadocia. Cambridge University Press, 1986, ISBN 978-0521267984

- Robert G. Ousterhout: A Byzantine Settlement in Cappadocia. Dumbarton Oaks Studies 42, Harvard University Press 2005, ISBN 0884023109 GoogleBooks

- Rainer Warland : Byzantine Cappadocia. Zabern, Darmstadt 2013, ISBN 978-3-8053-4580-4 .

Web links

- Cappadocian churches

- Katpatuka.org

- Exploration key

- Cappadocia Academy ( Memento from June 12, 2004 in the Internet Archive )

- Underground cities in Cappadocia - Myth and Reality (PDF; 587 kB)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Wolfgang Dorn: Turkey - Central Anatolia: between Phrygia, Ankara and Cappadocia . DuMont, 2006, ISBN 3770166167 , p. 15 at GoogleBooks

- ^ Wolf-Dieter Hütteroth / Volker Höhfeld: Turkey . Scientific Book Society Darmstadt 2002, p. 50 ISBN 3534137124

- ↑ Entry in the list of UNESCO World Heritage

- ↑ SpiegelOnline

- ↑ Elford / Graf: Journey into the past (Cappadocia) . AND Publishing House Istanbul, 1976

- ↑ a b c d Peter Daners, Volher Ohl: Cappadocia . Dumont 1996 ISBN 3-7701-3256-4

- ↑ Wolfgang Dorn. Turkey - Central Anatolia: between Phrygia, Ankara and Cappadocia . DuMont, 2006, ISBN 3770166167 , p. 283 at GoogleBooks

- ↑ Xenophon, Albert Forbiger. Xenophon's anabasis; or, Campaign of the Disciple Cyrus Langenscheidt, 1860 p. 22

- ↑ Critical edition of the Anabasis

- ↑ a b Katpatuka.org settlement history

- ↑ a b c Michael Bussmann / Gabriele Tröger: Turkey . Michael Müller Verlag 2004 ISBN 3-89953-125-6

- ↑ a b c Katpatuka.org cave churches

- ↑ Wolfgang Dorn. Turkey - Central Anatolia: between Phrygia, Ankara and Cappadocia . DuMont, 2006, ISBN 3770166167 , p. 349 at GoogleBooks

- ↑ katpatuka.org regional architecture ( Memento from June 12, 2004 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Cappadocia.dreipage.de ( Memento from January 6, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Agacalti Church

- ↑ Karanlik Church

- ^ Cappadocia Academy ( Memento from June 12, 2004 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ A b Robert G. Ousterhout: A Byzantine Settlement in Cappadocia. Dumbarton Oaks, 2005, p. 2 ISBN 0884023109 , at GoogleBooks

- ↑ Suchbuch.de