Lydia

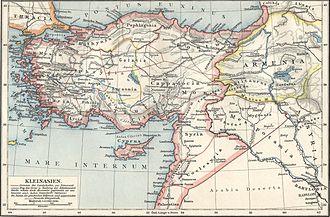

Lydia (Latin Lydia, also Mäonia ) is the name of a landscape in ancient times . It was located on the Mediterranean coast of Asia Minor in what is now Turkey opposite the islands of Lesbos , Chios and Samos off the coast . The area extended around today's İzmir to around Alaşehir inland. In Homeric times the area was called Maeonia by the Greeks . It was inhabited by the Lydians ( Maeons ).

geography

With regard to the borders, there was already a lack of clarity in ancient times. This is e.g. Partly due to the different reference objects: The borders of the Lydian kingdom or core area, the Lydian cultural area, the Lydian great empire, the Persian satrapy and the later province of the Diocletian reform can differ from one another quite considerably. On the other hand, one is dependent on a very thin cover (for example with the borders of the cultural area) and generally on unclear descriptions. Pliny the Elder gives a brief and equally vague description of the country: the center of the heartland was the mountain Tmolos , on which the capital of Sardis was, the Gygische See (today: Marmara Gölü ) and the surrounding fertile plain along the Hermos . In the south Lydia bordered on Caria , in the east on Phrygia , in the north on Mysia and in the west extended beyond Ionia . If one disregards the western border with Ionia, the description is considered correct. Specifically, there were no clear border lines, but border zones. The border zone in the south can be considered secure: Lydians and Karians alike settled in the Meander Valley. In the northeast, quasi between Lydia, Mysia and Phrygia, was the mountain Dindymos . The border zone between Lydia and Phrygia will probably have run along the rivers between Dindymos and Meander, the border zone between Lydia and Mysia probably along the Murat Dağı train; how far is unclear. The border between Ionia and Lydia is completely unclear, but the Sipylos seems to have been a border point. Zgusta, on the other hand, largely counts the coastal area as Lydia instead of Ionia; However, he is also interested in the cultural origins of places and less in the political and legal situation.

history

Periodization

In the past, very different, inconsistent periodization schemes were used in which archaeological and historical categories alternated. More recently, Roosevelt has developed a uniform scheme to address the methodological difficulties. This scheme is intended to be used here, slightly adapted to do justice to the expanded framework.

Prelydic period (before the 12th century BC)

For the Hermos Valley, a population can be proven as early as the Paleolithic , whose techniques point to connections to the Levant and Europe. A high level of cultural continuity can be established for the Copper Age , albeit with an orientation towards Central Anatolia. The cultural continuity also existed in the Bronze Age , but the population increased considerably, the material culture became more sophisticated and the exchange of goods in western and central Anatolia increased, as did long-distance trade. A population of Luwian-speaking people can be found in the area by the Bronze Age at the latest . In the late Bronze Age, the Luwian, political-cultural entity Arzawa became the most important power in the western Anatolian region, until it was established in the 14th century BC. Finally succumbed to the Hittite Empire . Successor states in the later Lydian area were Mira and especially the Seha river country , which, however, were vassals of the Hittites. Seha's center of power was in four citadels on Lake Gygian. After the collapse of the Hittite Empire in the early 12th century BC For several centuries BC, information on the area became scarce.

Early Lydian period (around 12th century to 7th century BC)

When the Lydians consolidated themselves as a separate entity remains the subject of the research discussion, because the sources only paint a very vague, mythically disguised picture. With regard to historical sources, it is always very difficult to decide whether a report is pure myth or contains a true core.

- The historical findings provide the central ambiguity. The term Lydia itself appears for the first time around the year 664 BC. In the Assyrian reports of the Rassam cylinder : There it is said that King Gugu of Luddu ( Gyges of Lydia) made contact with King Ashurbanipal . However, Homer mentions the inhabitants of the area in the Iliad - there they are called Maionier. The Maionier were identified with the Lydians as early as ancient times. Herodotus reports that before Gyges and the Mermnaden dynasty came to power, the Heraclid dynasty ruled the Lydians for 505 years; the fragments of the Xanthos also tell of the Heraclid dynasty. The thesis of the great emigration of the part of the population later known as the Etruscans is also linked to this period, and was already questioned in ancient times.

- The archaeological evidence is ambiguous. On the one hand, there is a clear continuity in the material culture from the Luwian to the clearly Lydian period; on the other hand, in the 12th century B.C. Significant destruction and a change in the center of power from the four citadels of Lake Gygi to the Acropolis of Sardis on Tmolos . The remains of this city are about ten kilometers west of today's Salihli in the western Turkish province of Manisa . The finding also suggests that the dominant language in the time before Gyges and after the collapse of the Hittite Empire was Lydian, and that the people who Homer referred to as Maionians were carriers of the Lydian and not the Luwian language.

- The linguistic findings indicate that the Lydian language is closely related on the one hand to the Indo-European languages Luwian and especially Hittite, but on the other hand is also clearly distinct. Before the 12th century, the bearers of this language were apparently located in the north-western region of Anatolia. With regard to the names of the rulers, there are some indications for a closeness to the Hittites: Sadyattes, Alyattes, etc. a. use the same tribe as Madduwatta , the Hittite vassal. However, there is a certain continuity of Luwian names with regard to the designation of the landmarks. Beekes plausibly advocates that the word for "Lydian" is derived from the word for "Luwish".

- The genetic evidence indicates that the inhabitants of the Seha river country of the 3rd millennium BC Were closely related to the later Lydians.

The following hypothesis can be derived from this: At the time of the Hittite rule, the carriers of the Lydian language (Prelyder) lived in northwest Anatolia, while carriers of the Luwian language (Luwier) lived in the Hermos Valley, on Lake Gygian and the Tmolos. At about the same time as the fall of the Hittite rule , the Phrygians immigrated to Asia Minor and pushed the Prelyder to the south, where they established themselves especially on the Tmolos. The Prelyder, known as Maionier in the Greek area, probably established a rule over the epichoric Luwians in the 12th century, but this was not particularly stable. Usually the beginning of the early Lydian period is set here. By the time the Gyges appeared, the Luwians and Maionians had largely merged into Lydians.

However, the question, considered by Josef Keil to be undecidable, whether the Lydians were a Phrygian tribe, has been decided: Pedley was already very skeptical about this thesis, it no longer plays a role in current research.

Middle Lydian period (about 7th century to 547 or 545 BC)

Only with Gyges (around 680 to 644 BC) did the Lydians become comprehensible in historical sources. Its historicity is certainly proven by the Rassam cylinder, and that of its usurpation can hardly be doubted. Whether it was a palace revolt or a “real civil war” cannot be decided for the current majority opinion of research, as there are quite contradicting reports. Some of them are hardly credible (with Plato , Gyges uses a ring that makes it invisible). Occasionally, an uprising against a Maionian foreign rule is assumed. Gyges is often linked to the defensive struggle against the invading Kimmerer - at the beginning successes were achieved: Gyges sent around the year 664 BC. Cimmerian prisoners as a gift to the court of the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal, probably to forge a defensive alliance. Since the Assyrian king did not want allies but subjects, Gyges failed. Nonetheless, Gyges waged war against some Anatolian Greek cities, where he probably failed at Miletus and Smyrna , but brought the Troas largely under Lydian control, and supported the independence struggle of the Egyptian king Psammetich I with a mercenary contingent. He died around the year 644 BC. In the vain defense of Sardis against the Kimmerer. The significant changes in Gyges' time were worked out by Dolores Hegyi .

The two successors Ardys (about 644 to 625 BC) and Sadyattes (about 625 to 600 BC) are hardly mentioned. They continued to wage war against the Cimmerians and Miletus, with Lydia under Ardys being a vassal kingdom of the Assyrians.

This was followed by Alyattes (605 to 561 BC), possibly the most successful Lydian king. Under him the Cimmerians were finally defeated, and he achieved successes against the Greeks of Asia Minor, including the conquest of Smyrna. He probably did not succeed in conquering Miletus, but did integrate it into his power system. In addition, after hard battles against the Medes, he expanded his empire in the east to Halys . He is also credited with the introduction of coinage, which made the economy flourish. Monumental buildings, including his own grave mound, underline the power of the Lydian king.

The last Lydian king is the best known: Kroisos (around 561 to 547 BC), as Croesus, has become the proverbial for wealth. This is likely due to the fact that the Lydian gold coins were known as Kroiseids in the Greek world and remained the standard currency in the Aegean for about 30 years even after Kroisos' death. He essentially continued the policy of the dynasty. This included the war against Anatolian Greek cities with the conquest of Ephesus and the general consolidation of rule in western Asia Minor. After the Persian Cyrus II had subjugated the Medes under King Astyages , Kroisos began the war against the Persian Empire with the support of an oracle from Delphi, which was formulated ambiguously according to ancient reports . The motivation is unclear, but the fact that his brother-in-law Astyages had just succumbed to an aggressor may have played a significant role. After initial successes, including the destruction of the city of Ptera , there was a great battle between the Lydians and the Persians, which did not bring any clear results. Kroisos withdrew to Lydia and released his mercenaries and allies according to the customs of the time in winter, but Cyrus took the opportunity, followed suit and put Kroisos, who could only muster a minimal army, before Sardis. Presumably, contrary to the reports of a heavenly salvation, Kroisos was executed by Cyrus.

Late Lydian period (about 547 to 217 BC)

After the conquest by Cyrus the Great, Lydia became the Persian satrapy Sparda (Persian for Sardis). The Lydians seem to have quickly come to terms with Persian rule: Under Paktyes , who was still appointed by Cyrus himself as treasurer , there was an unsuccessful uprising, then things remained quiet. Nevertheless, it was the scene of important events, which resulted mainly from the status of the "front city": It was seen by the Persians as the westernmost province and thus as a border to Greece. Sardis became the target of Greek military campaigns - during the Ionian uprising (500 to 494 BC) and the march of the Spartan king Agesilaus (396 to 394 BC) - and served as a deployment area for Persian military campaigns - in the run-up to the Greek campaign of Xerxes (480 BC) and the revolt of Cyrus the Younger (401 BC). But the royal peace brokered by the Persians between Sparta and their Greek enemies was also concluded in 387/6 BC. Signed in Sardis. How profound the changes in the administration of Lydia were, is the subject of the research discussion : Dusinberre assumes considerable changes such as a new tax system, Roosevelt from rather minor changes - only the elite would have been supplemented by Persians.

After the battle of Granikos in 334 BC The Persian garrison commander Mithrenes and the Lydian elite surrendered to Alexander the great without any problems . During the Hellenism , Sardis and Lydia remained involved in wars. After a short period of changes of rule (319 BC to Antigonos Monophthalmos , 301 BC to Lysimachos ) it came to 281 BC. To the Seleucid sphere of power , where, despite several attempts at conquest by Achaios (220–214) until 188 BC Chr. Remained. The Romans , victorious in the Battle of Magnesia , then handed it over to the Attalids , whose dynasty and rule in 133 BC. BC ended.

Alexander granted the Lydians a life according to traditional customs, but the Hellenization increased considerably: no later than 213 BC. BC Sardis was organized as a polis with a gerusia , popular assembly and Greek offices, and typical Greek facilities such as a theater and a grammar school were built; in addition, no inscriptions were made in Lydian. As a culture, the Lydians were in the late 3rd century BC. In the Hellenistic. Ratté points out that after the sack of Sardis in 217 BC By Antiochus III. and the reconstruction, the inhabitants had replaced their language and customs and thought of themselves as Greeks, but the city was in some ways firmly rooted in its glorious past. Certainly the Lydian period ended with the end of Lydian self-consciousness.

Post-Lydian period (late 3rd century BC and later)

In the late phase of Hellenism, the Roman Empire showed some activity in the former Lydian area: After the victory over Antiochus III. negotiations were conducted with the Seleucids in Sardis, as well as later with the Galatians . With the victory over the Seleucids, Asia Minor remained quiet for a long time. As with the death of Attalus III. When the Attalid dynasty ended, the ruler bequeathed his empire - and with it the former Lydian area - to the Romans. These released Sardis and other Lydian cities into independence, whereby they were firmly integrated into the Roman Amicitia system. Despite the fact that the Lydian cities remained relatively untouched by Vespers at Ephesus (88 BC) and the 1st Mithridatic War (89 to 84 BC), the area was reorganized as part of the reorganization of Asia Minor (84 BC) . Chr.) Through Sulla to part of the province of Asia . As a city loyal to the emperor, Sardis flourished again after a great earthquake (17 AD), as considerable funds were used for the reconstruction of the city: It remained a large, economically important city for a long time, but played neither politically nor politically a role in the military context. In the course of the Diocletian provincial reform in AD 297, a province of Lydia emerged again, which only consisted of the Hermos Valley, the heart of the Lydian culture, which was just slightly enlarged. It remained part of East Current or Byzantium , with Sardis and the surrounding area in 616/617 AD suffering massive destruction by the troops of the Sassanid Chosrau II . After that, Sardis remained a small castle until the Golden Horde of the Mongolian Timur finally destroyed it in 1405 AD.

society

Corporate structure

In general, a structure similar to medieval feudalism is assumed. At least in the Middle Lydian period, probably earlier, five groups can be made out: the house of the king, the elite (nobility and priests), the middle class (shopkeepers, traders, artisans), workers (free or semi-free tied to goods of the elite) and slaves. Further subdivisions are very unclear; from the names one can deduce from ancient times existing 'tribal structures'. It remains unclear to what extent the Lydian elite was replaced by Persians in the late Lydian period. It is certain that the most powerful men were replaced by the satrap , but that Lydians had the opportunity to pursue a certain career in the Persian system of rule. Whether administration and property generally remained in Lydian hands or whether entire tracts of land were given to Persian 'dukes' and 'knights' remains the subject of discussion.

military

The Greek tradition portrays the Lydians as effeminate barbarians, but this picture only emerged after Lydia had become Persian satrapy. In the early to middle Lydian times and probably later, the nobility established a building as early as the 6th century BC. BC militarily useless chariots and a feared cavalry. In the Middle Lydian period, the Lydian infantry was increased with Greek and Carian mercenaries. The armament of the Lydian soldiers was probably generally similar to that of the Greek. From two skeletons of Lydian soldiers who fell when the Persians conquered Sardis, it can be seen that heavy shields and helmets were used. Short sabers, war sickles, slingshots and bows and arrows have been identified as weapons. From the persistent and ultimately militarily unsuccessful campaigns of the Lydians, especially against Miletus , it is easy to deduce the low development of the Lydian siege system. On the other hand, Sardis could keep up with the strength of the defensive systems with the largest oriental cities and was superior to all Greek cities of his time.

economy

resources

The name Lydia has been associated with wealth since ancient times. Mostly it is mentioned in a prominent position that the Paktolos washes gold out of the Tmolos , which would have led to the wealth of the Lydians. The view was carried into the 20th century, but has been increasingly relativized in recent years. Indeed, Lydia was well positioned economically. First of all, there were the soils, with which, together with the mild climate, very good agricultural yields could be achieved. The uncultivated land also offered many grazing grounds and hunted animals, as well as forests that provided firewood and construction wood. In addition to the gold of the tmolos (as recent research has shown, it was actually gold and not electron , as was long assumed), iron, copper, lead and mineral deposits suitable for textile dyeing were found; there was also marble, limestone, jasper and a kind of onyx, which was named "Sardonyx" after the city of Sardis. Finally, the geostrategically favorable location should be mentioned: Lydia was located on the land route between the Anatolian highlands and the ports of the Aegean Sea .

Agriculture and animal husbandry

In terms of agriculture, Lydia did not differ much from most Greek cities. In addition to cereals, pulses, pumpkins and olives, a very popular wine was grown; Reddish figs were called "Lydian figs" and chestnuts "Sardinian acorns" in ancient times . Sheep played an important role in animal husbandry because of their wool. The same was true for horse breeding, but whether it was merely a reflection of prestige or whether it actually held a greater quantitative significance than cattle and goat husbandry remains unclear.

Ceramics, textiles and luxury items

Pottery was produced to a considerable extent in Lydia, and in some cases it was even of high quality. Outside Lydia, however, it was of little importance, apart from the "Lydion", a vessel for scented ointments. Greek ceramics, on the other hand, have been imported since the 9th century. As a result, Lydian ceramic production often expressed foreign influences. In the post-Lydian period, Lydian peculiarities disappeared very quickly and the products no longer differed from the Greek ones. In contrast to the Lydians' ceramic production, their textile production was widely famous. Apparently, Lydian carpets were popular at the Persian court, in the Greek region the chitons , into which gold threads were woven, and Sappho raved about colorful cloths (probably mitres ) and pliable boots. More notorious were the Sandykes, thin, flesh-colored chitons that made Lydian women appear naked in the eyes of Greeks. Occasionally these things were counted among the luxury items. Without a doubt, the scented ointments obtained from Bakkaris and Brenthon were part of it, as well as the jewelry made mainly of gold, electrum and silver, such as tiaras with rosette or animal motifs, earrings, pins or seals. The Lydian handicraft was not only famous for textile dyeing, but also especially for dyeing ivory.

trade

The considerable movement of goods has also contributed to economic prosperity. Herodotus ascribes the invention of retail trade to the Lydians - apparently many goods were produced centrally in Sardis and then distributed across the country by the "Kapeloi", a kind of peddler. They may also have been the first to sell pottery, etc. as shopkeepers. Herodotus also considers the Lydians to be the first innkeepers - perhaps this refers to caravanserai operators. Apparently only the mining and production of metals was controlled, initially by the Lydian royal house, later by Lydian nobles commissioned by the satrap. The best-known example is probably the promotion of the electrum and the minting of the Lydian coins. The processing of bronze, copper and iron was probably under similar control. It is possible that the stone carving was originally also in royal or noble hands; in any case, the production of Alyattes and Kroisos is strongly promoted. Finally, when comparing the cities of Gordion and Sardis, Hanfmann comes to the conclusion that Sardis differs from Gordion primarily through the lively trading and craft districts. Overall, a prosperous, cosmopolitan society is emerging. At least in Alyattes 'and Kroisos' time, Sardis was probably the wealthiest city in Western Anatolia and its most important hub in terms of trade - besides numerous Greek products, among other things, products from Phenicia and Assyria can be found in Sardis.

Coins

In the 7th century BC BC the first coins were issued as a means of payment , which represent the oldest coin finds in the Mediterranean region. The coin invention made the country's trade flourish. The Lydians initially minted electrum and later gold coins with lions' heads or lions and bulls. The invention of coinage was ascribed to them as early as ancient times. In fact, there is some evidence for this: at least the oldest gold coins are clearly Lydian - in the Greek world they are called "Kroiseids" after the last Lydian king Kroisos and were minted even after his execution. All older coins were minted from electrum - a connection to Lydien's electrum dust pactolus is obvious. Lydian letters are also found on some of the oldest coins. Finally, the high reputation of Lydian coins and the location of Sardis as a mint speak for it: They were used as the standard currency in the Aegean and the lion-and-bull motif remained for about 30 years, even if the artistic expression changed ( it became more stylized, metallic-harder, presumably because of the clearer lines required for mass production). Sardis also remained a mint for a long time - through the Persian period and Hellenism up to the Roman period. Howgego, on the other hand, questions this thesis: On the one hand, coins spread particularly quickly in the Greek area and, on the other hand, the oldest coins were found in a Greek city - Ephesus . However, the assertion that it is a purely Greek phenomenon seems to him to ignore the fact that it originated in the Lydian-Greek region. Furthermore, the thesis that the coins were minted to finance mercenaries, as represented by Hanfmann, among others, can hardly be substantiated. It seems to be certain that the refining of gold and silver practiced in Sardis by means of cementation of the electrum and the subsequent cupellation was a consequence of the increased demands of the coinage.

religion

overview

The Lydian religion is polytheistic, although it is not always clear, especially from the late Lydian epoch, how far one can speak of Lydian religion, because on the one hand there was considerable syncretism with Greek gods, many Greek gods were taken over and on the other hand, since later times many testimonies to the rapidly prevailing Hellenistic culture.

The central goddess was Kybele or Kuvava, which is closely linked to the Phrygian Cybele or Matar. She is mostly depicted as a female figure with lion companions. Artemis also received great veneration, e.g. B. from Kroisos . The Sardinian Artemis was also closely linked to the Ephesian Artemis. Kore, later identified with Persephone , was also venerated ; there are few material remains of worship here. Whether it was already venerated in the Middle Lydian epoch cannot be clearly established.

The worship of male gods has left fewer remains. Levs / Lefs (" Zeus ") seems to have been the central male god - his name is found most often. He is mostly depicted as a male figure holding an eagle and a scepter. It is possible that he was worshiped as "Zeus the city protector" together with Artemis in their temple - whether it was already in the Middle Lydian period is again unclear. Bacchus / Dionysus is identified with the Lydian Baki; Textual references and images of satyrs in Sardis make an active cult very likely. In addition, Lydia is named as the place of birth in Euripides ' play " Bakchen ", and there are Roman coins that indicate this performance.

Apollo and Qldans

The sacrifices of the Lydian kings at Delphi clearly show that Apollo was venerated - whether there were places of worship in Lydia itself is again unclear, but likely. Danielsson read the god name "+ ldans" as pldans and identified this god with Apollon, which was undisputed for a long time. Since Heubeck's argument against this reading, people have been more skeptical: Since then, the name of the gods has been read as qldans. He suggests identification with a moon god. Occasionally qldans is still identified with Apollo.

Hermes, Kandaules and the "puppy dinner"

Hermes is associated with Kandaules through a poem by Hipponax . Kandaules was apparently a Lydian god or demigod associated with theft or robbery. The nickname "Hundewürger" also refers to the "puppy dinner", the sacrifice of puppies as part of a ritual meal. There is evidence that this type of sacrifice persisted in a modified form until the Hellenistic period. Apparently the cult of Kandaules was closely linked to the Heraclid dynasty, because after the change to the Mermnad dynasty there are no more references to the Lydian nobility, instead references to the cult of Artemis are increasing. Appropriately, the last Heraclid king was called Kandaules .

Rooting Faith

Josef Keil divided the cults practiced in Lydia into different strata, which influenced one another. T. fused together, z. T. displaced each other, z. Some of them also existed side by side. He already stated that Anatolia looks like a closed unit, but that there are some corridors between Europe and the Levant that were significantly exposed to the influence of their larger neighbors, and remote, inaccessible regions in which epichoric peculiarities persisted much longer. Keil comes to the conclusion that of the 354 inscriptions of pagan worship, the vast majority of which come from Roman times, 112 ancient Anatolian deities are dedicated - tangible evidence of the enormous roots of these deities in the realities of the people of the Lydian region. This basic study has been expanded several times. Unsurprisingly, the Lydian inscriptions, which mostly from the 5th and 4th centuries BC A significant majority of Anatolian god names. In addition, the Hellenization affected the cities and less the country: There are references to corresponding rituals up to the 5th century AD. María Paz de Hoz starts from the existing results, updates them according to the state of research and thus provided a good eighty Years after Keil an overview. Religious practice in Lydia can be differentiated with regard to regional differences: a) the north-western area, b) the north-eastern area, c) the central section from west to east and d) the Kaystrostal . While the center and the Kaystrostal were fertile areas that were urbanized especially in the Seleucid period, the eastern part as a preliminary stage of the Anatolian highlands was rather difficult terrain; there the Greek influence was little for a long time. It can be shown that in the Hellenized West, the cults were also Hellenized and the inscriptions were more profane, aimed at external impact, whereas in the East they chose much more traditional forms and were more shaped by private piety. It is noticeable that the total number of epigraphic sources has more than doubled to 800; The number of names of Anatolian deities increased by far the strongest - from 112 to 565 - while that of the Greek gods hardly increased - from 117 to 159. From this it can be concluded that the other peoples ruling in Lydia hardly left any traces in the Lydian cult practice and it was not until Christianity began to displace the traditional cults in East Lydia in late antiquity. In contrast, Duisnberre assumes a considerable syncretism between ancient Anatolian and Persian gods cults in the late Lydian epoch.

Places of worship

Material remains of two temples have been found in Sardis, the Temple of Artemis and the Temple of Cybele; both were outside the city wall on the Paktolos . The Artemis Temple has a stepped foundation, as it is known from Persian tombs, the walls, etc., on the other hand, are clearly influenced by East Greek structures. Perhaps this is a case of syncretism. In Sardis there is also evidence of an altar dedicated to Cybele. This was part of the gold refinery in the Middle Lydian epoch, which was probably shut down during the Achaemenid rule . Subsequently, the temple was revised and converted into a Persian fire temple . In addition, Cybele was worshiped as Metroon, the divine mother, in another temple. There were other holy places and places of worship outside of Sardis. The Gygische See was connected with the cult of Cybele; However, it cannot be said for certain. The cult of Artemis Koloene (lyd. Kulumsis ) is also linked to this lake . Other places of worship are likely to have been peaks of hills or mountains. The city of Hypaipa , where the cult of the Persian Artemis (Artemis Anaitis) was practiced, received special attention ; apparently a sacred road connected Sardis and Hypaipa. Another Persian sanctuary was in Hieracome . An important place of worship was the monumental figure of Hittite origin at the foot of Mount Sipylos , which in Lydian times was considered an image of Cybele. Zeus, on the other hand, seems to have been worshiped on the one hand on Mount Karios and on the other hand in Dioshieron .

art

Visual arts

The vast majority of evidence of Lydian art come from the visual arts, which includes not only works of painting, sculpture and architecture but also jewelry.

Painting finds expression in wall paintings and ceramics; reliefs and statues were also painted. In the case of the wall paintings, the sources are very thin. The remains can be found in Lydian tumulus graves and therefore probably represent scenes from the life of the dead or ideas of the realm of the dead: frequent subjects are hunting and banquet scenes. Little can be seen of the style; it was probably very similar to the style common in the Aegean Sea . There are essentially two styles of ceramic vessels: the mostly simple monochrome or geometric Anatolian tradition and the more elaborate figurative Greek tradition, which is particularly oriented towards the orientalizing Eastern Greek tradition. Apparently, in the time of the Alyattes, the technique of making painted ceramic tiles was adopted by the Greeks. In the Middle Lydian and Late Lydian epoch, houses were probably increasingly decorated with them; much is still very unclear here.

The surviving works of sculpture come mainly from the late Lydian era, as they are often grave steles and grave reliefs from the area around Tumuli. The pictorial representations usually show the deceased at a banquet. In the non-figurative representations, volutes and palmettes dominate . There are also reliefs from the area around temples and other religiously motivated representations - they mostly show gods. There are still numerous free-standing statues. There are very few anthropomorphic figures here; probably again representations of gods or representations of mythical beings. However, there are numerous statues that depict animal beings, often lions, lion griffins or sphinxes and eagles. Another Lydian peculiarity are the so-called phallos markers: mushroom-shaped steles that can be found near or on tumuli. Originally they were thought to be Phallos symbols, but today research has moved away from this idea.

The architecture is usually not praised. Herodotus' message is formative that the houses of Sardis are huts that are roofed with thatch. In contrast, the impressive monumental buildings are to be kept: the city wall of Sardis, the terraces of Sardis and the tumuli are occasionally considered to be evidence of Lydian architecture. The city wall was built in the late 7th or early 6th century BC. BC and on average 15 m high and 20 m wide. The terraces were huge limestone platforms that probably divided Sardis into upper and lower town; probably the palace of Kroisos , the central administration and representative building, stood on such a terrace. The tumuli are barrows that arose mainly in the late Lydian epoch; at first it was presumably exclusively royal tombs, later then general graves for the Lydian elite. It is speculated that the significant increase in the early period of Persian rule was a sign of the cultural isolation of the Lydian elite. Herodotus compares the large tumulus, which was later identified as the tomb of Alyattes , with the great Egyptian pyramids - in fact, the volume is only slightly smaller. The burials in burial chambers that were carved directly into the rock faces of the mountains also attracted attention; Little attention is paid to the stone boxes and direct burials. The Lydian jewelry was widely known and respected in ancient times. The oriental-looking decorations (sphinxes, lion heads) probably refer to Assyrian and late Hittite motifs via Greek mediation . A very interesting piece is a small ivory head that depicts a young woman's face with moon-shaped brand marks on the cheeks - probably a slave of the moon god. The "Lydian Treasure", a compilation that is occasionally assigned to Karun Hazineleri , a rich man of antiquity, or Kroisos, gives an impressive overview of the art works . In fact, it was stolen from a number of tumuli and therefore probably belongs to the late Lydian era. It consists of 363 objects. Overall, it can be said that the visual arts of the Lydians sought a close relationship to religious topics and was clearly influenced by the cultures of the environment.

music

In Lydian music, according to the Greek sources, mainly bright, high and shrill tones were used. The paktís , probably a kind of harp or lyre , the bárbitos , possibly a kind of deeper lyre, the mágadis , perhaps a drum, a flute or rather a lyre, and a kind of triangle are ascribed to them as instruments .

Theater, poetry

There are no references to these arts.

Culture

overview

The most influential, most reflective news about the Lydian way of life comes from Greek sources. On the one hand, they originated at a time when even the nobility in Greece was in a crisis that was very much associated with dealing with luxury (cf. Athenian luxury laws ). From this point of view, the luxury of the Lydians, which undoubtedly existed to a considerable extent, was particularly reflected: in part, a "Lydian fashion" was lived out, a sought-after painter of Athens was called "the Lydian" and a nobleman named his son " Kroisos "; T. was strongly criticized; It finds a climax in the story that one night the Lydian king Kambles slaughtered and eaten his wife in his greed. On the other hand, some sources come from the later period, in which Herodotus' dictum that the Persian king Cyrus II practically forced this luxury on the Lydians in order to soften them was generally adopted; they tend to be at least negative about Lydian luxury. On the other hand, Herodotus' remark that the Lydian customs hardly differed from the Greek is largely overlooked.

luxury

It can be taken for granted that in Sardis in the time of Alyattes and Kroisos the elite had some wealth and displayed it in a representative way. This included jewelry, perfumes, lavishly colored clothing, which was also draped in such a way that it took some practice to be able to walk elegantly, and elaborately designed hairstyles. In fact, the production of cosmetics and their containers played such a large role that one can speak of an industry. At least z. T. also the horse hobby of the Lydian nobility can be seen in the context of the representative wealth. The fact that in late Lydian Sardis a drinking bowl associated with the Persian nobility, originally a luxury vessel made of gold or silver, was copied from ceramic for the poorer Lydians in this direction can also be interpreted. What is astonishing, on the other hand, is the tenacity with which broken ceramics were mended or used for purposes other than intended.

food

The basic structure of the meals did not differ significantly from those of the Greeks; According to archaeological findings, stew-style dishes may have been more popular. The “kandaulos” stew, which is associated with the god's name Kandaules and the puppy dinner because of the similarity of its name, achieved some fame, even if no dog meat was eaten. A type of blood soup called "karyke" was also known. The Lydian bakers were also highly praised by the Greeks, and their breads were often praised. The desserts match the luxury topos: there were pancakes with sesame seeds, waffles with honey and a kind of nougat. Lydian wine was also valued. Mugs with a tap or strainer indicate beer or possibly mead, fermented milk (kumys), barley water or herbal teas.

prostitution

The main difference between Greek and Lydian customs is the Lydian tradition, according to which unmarried women earn their dowry through prostitution, reports Herodotus. It is commonly believed by research that Herodotus confused an aspect of temple prostitution with regular prostitution. Ludwig Bürchner already remarked laconically: “Phallosdienst is nature service.” This position is still widely held. Recently, however, the institution of temple prostitution has been massively questioned by Tanja Scheer .

Female eunuchs

The news going back to Xanthos that the Lydians had turned women into eunuchs and needed them accordingly was little treated . Usually it is ignored as Greek rhetoric. George Devereux, however, investigates the question and comes to the conclusion that reinfibulation seems unlikely, but is not ruled out, but that Xanthos probably describes cauterization of the female genital organ.

language

The Lydian language is largely derived from inscriptions from around 600 to the 4th century BC. Reconstructed (the oldest inscription from the second half of the 7th century BC from Egypt - it was probably left by one of the mercenaries that Gyges sent to Pharaoh Psammetich I ); apparently the language was no longer written soon after the fall of the Persian Empire . Strabo reports that in his time Lydian was only spoken in Kibyra .

Lydian belongs to the Anatolian language group of the Indo-European language family . The special connection to the languages Hittite and Palai spoken in the north of Asia Minor is certain , but a communis opinio to the Luwian idioms has not yet been achieved.

The alphabet with twenty-six characters was probably developed on the model of the Eastern Greek alphabet, with the characters that represent unused sounds being given new sound values; for other sound values required, new characters were developed or borrowed from other alphabets. The direction of the writing in most texts is left-handed, rarely right-handed or bustrophedon . The words are usually separated by a clear space.

See also

literature

Overview representations

- Ludwig Bürchner , Gerhard Deeters , Josef Keil : Lydia. In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume XIII, 2, Stuttgart 1927, Sp. 2122-2202.

- Clive Foss: Lydia. In: Real Lexicon for Antiquity and Christianity . Volume 23, Hiersemann, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-7772-1013-1 , Sp. 739-762

- Hans Kaletsch : Lydia. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 7, Metzler, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-476-01477-0 , Sp. 538-547.

- George MA Hanfmann : Sardis and Lydien (= treatises of the humanities and social sciences class of the Academy of Sciences and Literature in Mainz. Born in 1960, No. 6).

- Horst Schäfer-Schuchardt: Ancient metropolises - gods, myths and legends. The Turkish Mediterranean coast from Troy to Ionia. Belser, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-7630-2385-2 , pp. 55-73. - (Overview of Sardis , Magnesia on Sipylos , Aigai , Philadelphia , Smyrna )

Investigations

- Elmar Schwertheim : Asia Minor in Antiquity. From the Hittites to Constantine. Beck, Munich 2005, pp. 28-32

- Christian Marek : History of Asia Minor in Antiquity. 2nd Edition. Beck, Munich 2010, pp. 152–159

- John Griffiths Pedley: Ancient Literary Sources on Sardis (= Archaeological Exploration of Sardis , Monograph 2). Cambridge (Massachusetts) 1972.

- Christopher H. Roosevelt: The Archeology of Lydia. From Gyges to Alexander. Cambridge et al. 2009.

- Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Yapı Kredi Yayınları, Istanbul 2010, ISBN 978-975-08-1746-5 .

- Annick Payne, Jorit Wintjes: Lords of Asia Minor. An Introduction to the Lydians. Wiesbaden 2016, ISBN 978-3-447-10568-2

Web links

- Jona Lendering: Lydia . In: Livius.org (English)

- The Archaeological Exploration of Sardis. Digital Resource Center

Individual evidence

- ↑ gates Kjeilen: Lydia. (No longer available online.) LookLex Encyclopaedia, archived from the original on August 29, 2011 ; accessed on August 22, 2011 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Strabo 13.1.3

- ↑ Pliny, Naturalis Historia 5.110

- ↑ Christopher H. Roosevelt: The Archeology of Lydia, From Gyges to Alexander. Cambridge et al. 2009, Chapter 3: Lydian Geography and Environment, pp. 33-58.

- ↑ Ladislav Zgusta: Asia Minor place names. Heidelberg 1984.

- ↑ E.g. George MA Hanfmann: Sardis and Lydien. Mainz / Wiesbaden 1960 (treatises of the humanities and social sciences class, born 1960 - No. 6)

- ↑ Christopher H. Roosevelt: The Archeology of Lydia, From Gyges to Alexander. Cambridge et al. 2009, Chapter 2: The Cultural and Historical Framework, pp. 11-13.

- ↑ Christopher Roosevelt: Lydia Before the Lydians. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, pp. 47–56.

- ^ Maciej Popko : Peoples and Languages of Old Anatolia. Wiesbaden 2008, pp. 65–72 (3. Anatolian peoples and languages, 3.1 In the 2. Millennium BC, 3.1.3. The Luwians), more precise and up-to-date: H. Craig Melchert (Ed.), The Luwians, Brill 2003.

- ↑ Christopher Roosevelt: Lydia Before the Lydians. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, pp. 52–53.

- ↑ Christopher H. Roosevelt: The Archeology of Lydia, From Gyges to Alexander. Cambridge et al. 2009, Chapter 2: The Cultural and Historical Framework, p. 23.

- ↑ Homer, Iliad, 2,864-866; 5.43-44

- ↑ Herodotus 1.7; Pliny the Elder, Natural History 5,110

- ↑ Herodotus 1.7

- ↑ Hans Diller: Two stories of the Lyders Xanthos. In: Navicula Chiloniensis. Leiden 1956, pp. 66-78.

- ↑ a b c Herodotus 1.94

- ↑ Dionysius of Halicarnassus, History of Rome 1,30,1

- ↑ Christopher Roosevelt: Lydia Before the Lydians. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, pp. 57-60.

- ^ Onofrio Carruba: Lydisch and Lyder. In: Communications from the Institute for Orient Research. 8 (1963), pp. 381-408 and H. Craig Melchert: Lydian Language and Inscriptions. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, pp. 269–270.

- ↑ John Griffiths Pedley: Sardis in the Age of Croesus. Norman 1968 (The Centers of Civilization Series), I. Sardis and Lydia, p. 27 and Dolores Hegyi: Changes in Lydian Politics and Religion in Gyges' Time. In: Acta Academiae. Scientiarum Hungaricae. 43 (2003), p. 4.

- ↑ Christopher Roosevelt: Lydia Before the Lydians. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, p. 58.

- ↑ Robert Beekes: Luwians and Lydians. In: Kadmos. 42 (2003), pp. 47-49.

- ↑ Christopher H. Roosevelt: The Archeology of Lydia, From Gyges to Alexander. Cambridge et al. 2009, Chapter 2: The Cultural and Historical Framework, pp. 13-14.

- ↑ Robert Beekes: Luwians and Lydians. In: Kadmos. 42 (2003), pp. 47-49 and H. Craig Melchert: Lydian Language and Inscriptions. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, pp. 266-272.

- ↑ John Griffiths Pedley: Sardis in the Age of Croesus. Norman 1968 (The Centers of Civilization Series), I. Sardis and Lydia, p. 34, renewed in Dolores Hegyi: Changes in Lydian Politics and Religion in Gyges' Time. In: Acta Academiae. Scientiarum Hungaricae. 43 (2003), pp. 1-14.

- ↑ Christopher H. Roosevelt: The Archeology of Lydia, From Gyges to Alexander. Cambridge et al. 2009, Chapter 7: Conclusions: Continuity and Change at Sardis and Beyond, pp. 191-194.

- ↑ Christopher H. Roosevelt: The Archeology of Lydia, From Gyges to Alexander. Cambridge et al. 2009, Chapter 2: The Cultural and Historical Framework, pp. 13-22, and Hans Kaletsch: Lydia. In: DNP. 7 (1999), p. 539

- ^ H. Craig Melchert: Lydian Language and Inscriptions. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, pp. 266-272.

- ^ Josef Keil [20], Lydia, RE XIII 2 (1927), 2166.

- ↑ John Griffiths Pedley: Sardis in the Age of Croesus. Norman 1968 (The Centers of Civilization Series), I. Sardis and Lydia, pp. 21-37.

- ↑ Otto Seel: Herakliden and Mermnaden. In: Navicula Chiloniensis. (Festschrift for F. Jacoby), Leiden 1956, p. 45.

- ^ Heinrich Gelzer: The age of Gyges. Second part, In: Rheinisches Museum für Philologie. 35 (1880), p. 518.

- ↑ Christopher H. Roosevelt: The Archeology of Lydia, From Gyges to Alexander. Cambridge et al. 2009, Chapter 2: The Cultural and Historical Framework, pp. 22-23.

- ↑ Plato, Politeia 359E

- ↑ Dolores Hegyi: Changes in Lydian Politics and Religion in Gyges' Time. In: Acta Academiae. Scientiarum Hungaricae. 43 (2003), p. 4.

- ↑ John Griffiths Pedley: Sardis in the Age of Croesus. Norman 1968 (The Centers of Civilization Series), II. The Mermnad Dynasts, pp. 44-50.

- ↑ Dolores Hegyi: Changes in Lydian Politics and Religion in Gyges' Time. In: Acta Academiae. Scientiarum Hungaricae 43 (2003), pp. 1-14.

- ↑ John Griffiths Pedley: Sardis in the Age of Croesus. Norman 1968 (The Centers of Civilization Series), II. The Mermnad Dynasts, pp. 50-52.

- ↑ Herodotus 1:16

- ↑ Herodotus 1: 17-22; John Griffiths Pedley: Sardis in the Age of Croesus. Norman 1968 (The Centers of Civilization Series), II. The Mermnad Dynasts, p. 53.

- ↑ Herodotus 1: 72-74

- ↑ John Griffiths Pedley: Sardis in the Age of Croesus. Norman 1968 (The Centers of Civilization Series), III. Dust to Dust, pp. 74-75, John H. Kroll: The Coins of Sardis. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, pp. 143–146.

- ↑ Christopher H. Roosevelt: The Archeology of Lydia, From Gyges to Alexander. Cambridge et al. 2009, Chapter 7: Conclusions: Continuity and Change at Sardis and Beyond, p. 189.

- ↑ John H. Kroll: The Coins of Sardis. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, pp. 150–153.

- ↑ Herodotus 1: 26-27

- ↑ John Griffiths Pedley: Sardis in the Age of Croesus. Norman 1968 (The Centers of Civilization Series), IV. Croesus: Rise and Fall, pp. 79-99.

- ↑ Herodotus 1.71

- ↑ Christopher H. Roosevelt: The Archeology of Lydia, From Gyges to Alexander. Cambridge et al. 2009, Chapter 2: The Cultural and Historical Framework, p. 26.

- ↑ a b Herodotus 1.76

- ↑ Herodotus 1.77; 1.79

- ↑ Herodotus 1.87

- ↑ Herodotus 1: 53-54

- ↑ John Griffiths Pedley: Sardis in the Age of Croesus. Norman 1968 (The Centers of Civilization Series), Prologue: The Historical City, p. 5)

- ↑ Persian inscription: Darios, Persepolis H

- ↑ Herodotus 5.99-100

- ↑ Xenophon, Hellenika 3, 4, 21

- ↑ Herodotus 7: 32-37

- ↑ Xenophon, Anabasis 1,2,2-3

- ^ Elspeth RM Dusinberre: Aspects of Empire in Achaemenid Sardis. Cambridge et al. 2003.

- ↑ Christopher H. Roosevelt: The Archeology of Lydia, From Gyges to Alexander. Cambridge et al. 2009.

- ↑ Plutarch, Alexander 17

- ↑ Hans Kaletsch: Lydia. In: DNP. 7: 541 (1999)

- ↑ George MA Hanfmann: Sardis and Lydia. Mainz / Wiesbaden 1960 (treatises of the humanities and social sciences class, born 1960 - No. 6) and Christopher Ratté: Reflections on the Urban Development of Hellenistic Sardis. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): Love for Lydia. A Sardis Anniversary Volume Presented to Crawford H. Greenewalt, Jr. Cambridge, London 2008 (Report / Archaeological Exploration of Sardis, Vol. 4), pp. 128-130.

- ↑ Christopher H. Roosevelt: The Archeology of Lydia, From Gyges to Alexander. Cambridge et al. 2009, Chapter 2: The Cultural and Historical Framework, p. 31.

- ^ Christopher Ratté: Reflections on the Urban Development of Hellenistic Sardis. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): Love for Lydia. A Sardis Anniversary Volume Presented to Crawford H. Greenewalt, Jr. Cambridge, London 2008 (Report / Archaeological Exploration of Sardis, Vol. 4), p. 133.

- ↑ Polybios 21,16,1-2; 31.6

- ↑ Livy 45:43, 11

- ↑ George MA Hanfmann: Sardis and Lydia. Mainz / Wiesbaden 1960 (treatises of the humanities and social sciences class, born 1960 - No. 6)

- ↑ Hans Kaletsch: Lydia. In: DNP. 7: 542 (1999)

- ↑ John Griffiths Pedley: Sardis in the Age of Croesus. Norman 1968 (The Centers of Civilization Series), Prologue: The Historical City, pp. 18-19.

- ↑ Fundamental: Heinrich Gelzer: The Age of Gyges. Second part, In: Rheinisches Museum für Philologie. 35: 518-526 (1880); Current: Christopher H. Roosevelt: The Archeology of Lydia, From Gyges to Alexander. Cambridge et al. 2009, Chapter 4: Settlement and Society at Sardis, pp. 85-87.

- ↑ Little Persian presence: Christopher H. Roosevelt: The Archeology of Lydia, From Gyges to Alexander. Cambridge et al. 2009, Chapter 4: Settlement and Society at Sardis, pp. 88-89; strong Persian presence: Nicholas Victor Seconda: Achaemenid Colonization in Lydia. In: Revue des études anciennes . 87: 9-13 (1985).

- ↑ John Griffiths Pedley: Sardis in the Age of Croesus. Norman 1968 (The Centers of Civilization Series), II. The Mermnad Dynasts, p. 38.

- ↑ Hans Kaletsch: Lydia. In: DNP. 7: 543-544 (1999)

- ↑ Nicholas Cahill: The Persian Sack of Sardis. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, pp. 339–361.

- ↑ John Griffiths Pedley: Sardis in the Age of Croesus. Norman 1968 (The Centers of Civilization Series), II. The Mermnad Dynasts, pp. 38-57.

- ↑ Nicholas Cahill: The City of Sardis. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, p. 80.

- ↑ Hans Kaletsch: Lydia. In: DNP. 7 (1999), col. 543.

- ^ Annick Payne and Jorit Wintjes: Lords of Asia Minor. An Introducion to the Lydians, Wiesbaden 2016, p. 17.

- ↑ Christopher H. Roosevelt: The Archeology of Lydia, From Gyges to Alexander. Cambridge et al. 2009, Chapter 3: Lydian Geography and Environment, pp. 47-58.

- ↑ Michael Kerschner: The Lydians and Their Ionian and Aiolian Neighbors. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, pp. 247–248.

- ↑ Christopher H. Roosevelt: The Archeology of Lydia, From Gyges to Alexander. Cambridge et al. 2009, Chapter 3: Lydian Geography and Environment, pp. 49-54.

- ↑ Crawford H. Greenewalt, Jr .: Lydian Pottery. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, pp. 106–124.

- ↑ George MA Hanfmann: Sardis and Lydia. Mainz / Wiesbaden 1960 (treatises of the humanities and social sciences class, born 1960 - No. 6), p. 514.

- ↑ See Crawford H. Greenewalt, Jr .: Lydian Pottery. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, pp. 110-118; Ekrem Akurgal: The Art of Anatolia. From Homer to Alexander. Berlin 1961, Lydische Kunst, pp. 151–152; Elspeth RM Dusinberre: Aspects of Empire in Achaemenid Sardis. Cambridge et al. 2003, chap. 8. Achaemenid bowls: ceramic assemblages and the non-elite, pp. 172–195.

- ↑ George MA Hanfmann: Sardis and Lydia. Mainz / Wiesbaden 1960 (treatises of the humanities and social sciences class, year 1960 - No. 6), p. 529.

- ↑ Crawford H. Greenewalt, Jr., Lawrence J. Majewski: Lydian Textiles. In: Keith De Vries (Ed.): From Athens to Gordion. The Papers of a Memorial Symposium for Rodney S. Young. Philadelphia 1980 (University Museum Papers Vol. 1), pp. 135-138.

- ↑ Crawford H. Greenewalt, Jr .: Lydian Cosmetics. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, pp. 201-216.

- ↑ Yildiz Akyay Mericboyu: Lydian Jewelry. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, pp. 157–176.

- ↑ Christopher H. Roosevelt: The Archeology of Lydia, From Gyges to Alexander. Cambridge et al. 2009, Chapter 4: Settlement and Society at Sardis, pp. 70-73.

- ↑ John Griffiths Pedley: Sardis in the Age of Croesus. Norman 1968 (The Centers of Civilization Series), III. Dust to Dust, pp. 75-78.

- ↑ Hans Kaletsch: Lydia. In: DNP. 7: 544 (1999).

- ↑ Christopher H. Roosevelt: The Archeology of Lydia, From Gyges to Alexander. Cambridge et al. 2009, Chapter 4: Settlement and Society at Sardis, pp. 74-77.

- ↑ George MA Hanfmann, On Lydian Sardis. In: Keith De Vries (Ed.): From Athens to Gordion. The Papers of a Memorial Symposium for Rodney S. Young. Philadelphia 1980 (University Museum Papers Vol. 1), pp. 106-107.

- ↑ Christopher H. Roosevelt: The Archeology of Lydia, From Gyges to Alexander. Cambridge et al. 2009, Chapter 4: Settlement and Society at Sardis, p. 88.

- ↑ John H. Kroll: The Coins of Sardis. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, pp. 143-150.

- ↑ John Griffiths Pedley: Sardis in the Age of Croesus. Norman 1968 (The Centers of Civilization Series), III. Dust to Dust, pp. 70-75.

- ↑ John H. Kroll: The Coins of Sardis. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, pp. 150–154.

- ↑ Christopher Howgego: Money in the Ancient World. An introduction. Darmstadt 2011, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Cf. Christopher Howgego: Money in the Ancient World. An introduction. Darmstadt 2011, p. 3; George MA Hanfmann: Sardis and Lydia. Mainz / Wiesbaden 1960 (treatises of the humanities and social sciences class, year 1960 - No. 6), p. 517.

- ↑ See Crawford H. Greenewalt, Jr .: Gold and Silver Refining at Sardis. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, pp. 134–141.

- ↑ Crawford H. Greenewalt, Jr .: The Gods of Lydia. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, pp. 233-237.

- ↑ Crawford H. Greenewalt, Jr .: The Gods of Lydia. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, pp. 237-238.

- ↑ Crawford H. Greenewalt, Jr .: The Gods of Lydia. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, p. 238.

- ^ OA Danielsson: On the Lydian inscriptions. Uppsala 1917, p. 24.

- ↑ Alferd Heubeck: Lydiaka. Studies on script, language and god names of the Lydians. Erlangen 1959 (Erlangen Research, Series A: Humanities Vol. 9)

- ↑ Hans Kaletsch: Lydia. In: DNP. 7 (1999), col. 544.

- ↑ Crawford H. Greenewalt, Jr .: The Gods of Lydia. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, pp. 238-240; Crawford H. Greenewalt, Jr .: Ritual Dinners in Early Historic Sardis. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London 1976 (University of California Publications: Classical Studies, Vol. 17), Chap. 5. The Dinners' Recipient, pp. 45-55.

- ↑ Dolores Hegyi: Changes in Lydian Politics and Religion in Gyges' Time. In: Acta Academiae. Scientiarum Hungaricae. 43 (2003), pp. 5-13.

- ^ Josef Keil: The cults of Lydia. In: WH Buckler, WM Calder (ed.): Anatolian Studies presented to Sir William Mitchell Ramsay. Manchester 1923.

- ↑ JH Jongkees: God's names in Lydian inscriptions. In: Mnemosyne. Series III, 6 (1938), pp. 355-367.

- ^ Georg Petzl: Rural Religiousness in Lydia. In: Elmar Schwertheim (Ed.): Research in Lydia. Bonn 1995, pp. 37-48 + plates 5-8.

- ↑ María Paz de Hoz: The Lydian cults in the light of the Greek inscriptions. Bonn 1999 (Asia Minor Studies Vol. 36)

- ^ Elspeth RM Dusinberre: Aspects of Empire in Achaemenid Sardis. Cambridge et al. 2003, chap. 9. Conclusion: Imperialism and Achaemenid Sardis, pp. 201-203.

- ^ For this: Elspeth RM Dusinberre: Aspects of Empire in Achaemenid Sardis. Cambridge et al. 2003, chap. 3. The urban structure of Achaemenid Sardis: monuments and meaning, pp. 60-64; skeptical: Christopher H. Roosevelt: The Archeology of Lydia, From Gyges to Alexander. Cambridge et al. 2009, Chapter 4: Settlement and Society at Sardis, p. 80.

- ^ Elspeth RM Dusinberre: Aspects of Empire in Achaemenid Sardis. Cambridge et al. 2003, chap. 3. The urban structure of Achaemenid Sardis: monuments and meaning, pp. 64-68.

- ↑ Christopher H. Roosevelt: The Archeology of Lydia, From Gyges to Alexander. Cambridge et al. 2009, Chapter 4: Settlement and Society at Sardis, pp. 82-83.

- ↑ Christopher H. Roosevelt: The Archeology of Lydia, From Gyges to Alexander. Cambridge et al. 2009, Chapter 5: Settlement and Society in Central and Greater Lydia, pp. 123-129.

- ↑ Ilknur Özgen: Lydian Treasure. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, pp. 324–327.

- ↑ Crawford H. Greenewalt, Jr., Lydian Pottery. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, pp. 109-118; Ekrem Akurgal: The Art of Anatolia. From Homer to Alexander. Berlin 1961, Lydische Kunst, pp. 151–152.

- ↑ Eric Hostetter: Lydian Architectural Terracottas. A Study in Tile Replication, Display and Technique. The Archaeological Exploration of Sardis. Atlanta 1994 (Illinois Classical Studies Supplement 5); Suat Ateslier: Lydian Architectural Terracottas. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, pp. 224-232.

- ↑ Christopher H. Roosevelt: The Archeology of Lydia, From Gyges to Alexander. Cambridge et al. 2009, Chapter 6: Burial and Society, pp. 155-173; Elspeth RM Dusinberre: Aspects of Empire in Achaemenid Sardis. Cambridge et al. 2003, chap. 4. The urban structure of Achaemenid Sardis: sculpture and society, pp. 90-112.

- ↑ Ekrem Akurgal: The Art of Anatolia. From Homer to Alexander. Berlin 1961, Lydian Art, p. 153.

- ↑ Elizabeth Baughan: Lydian Burial Customs. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, p. 278.

- ↑ Herodotus 5.101

- ↑ Christopher H. Roosevelt: The Archeology of Lydia, From Gyges to Alexander. Cambridge et al. 2009, Chapter 4: Settlement and Society at Sardis, pp. 78-79; Nicholas Cahill: The City of Sardis. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, pp. 77-81.

- ↑ Nicholas Cahill: The City of Sardis. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, pp. 85-86; Nicholas D. Cahill: Mapping Sardis. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): Love for Lydia. A Sardis Anniversary Volume Presented to Crawford H. Greenewalt, Jr. Cambridge, London 2008 (Report / Archaeological Exploration of Sardis, Vol. 4), pp. 119-120.

- ↑ Elizabeth Baughan: Lydian Burial Customs. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, pp. 275-282.

- ^ Elspeth RM Dusinberre: Aspects of Empire in Achaemenid Sardis. Cambridge et al. 2003, chap. 6. Mortuary evidence: dead and living societies, pp. 138-145.

- ↑ Christopher H. Roosevelt: The Archeology of Lydia, From Gyges to Alexander. Cambridge et al. 2009, Chapter 6: Burial and Society, pp. 140-151.

- ↑ Christopher H. Roosevelt: The Archeology of Lydia, From Gyges to Alexander. Cambridge et al. 2009, Chapter 6: Burial and Society, pp. 133-138; Elizabeth Baughan: Lydian Burial Customs. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, pp. 282–287.

- ↑ Ekrem Akurgal: The Art of Anatolia. From Homer to Alexander. Berlin 1961, Lydische Kunst, pp. 156–159.

- ↑ Ilknur Özgen: Lydian Treasure. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, pp. 305-324.

- ↑ John Griffiths Pedley: Sardis in the Age of Croesus. Norman 1968 (The Centers of Civilization Series), V. The Arts of Lydia, pp. 100-113.

- ↑ John Griffiths Pedley: Sardis in the Age of Croesus. Norman 1968 (The Centers of Civilization Series), V. The Arts of Lydia, pp. 1113-115.

- ↑ John Griffiths Pedley: Sardis in the Age of Croesus. Norman 1968 (The Centers of Civilization Series), V. The Arts of Lydia, p. 113.

- ↑ George MA Hanfmann: Sardis and Lydia. Mainz / Wiesbaden 1960 (treatises of the humanities and social sciences class, year 1960 - No. 6), p. 518.

- ↑ Erich Kistler: À la lydienne ... more than just a fashion. In: Linda-Marie Günther (Ed.): Tryphe and cult ritual in archaic Asia Minor - ex oriente luxuria? Wiesbaden 2012, pp. 67-68.

- ↑ Herodotus 1: 55-56

- ↑ John Griffiths Pedley: Sardis in the Age of Croesus. Norman 1968 (The Centers of Civilization Series), VI. The City and Its Citizens, pp. 133-134; Erich Kistler: À la lydienne ... more than just a fashion. In: Linda-Marie Günther (Ed.): Tryphe and cult ritual in archaic Asia Minor - ex oriente luxuria? Wiesbaden 2012, p. 63.

- ↑ Crawford H. Greenewalt, Jr .: Lydian Cosmetics. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, pp. 205-210.

- ^ Crawford H. Greenewalt, Jr .: Horsemanship. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, pp. 217-218.

- ^ Elspeth RM Dusinberre: Aspects of Empire in Achaemenid Sardis. Cambridge et al. 2003, chap. 8. Achaemenid bowls: ceramic assemblages and the non-elite, pp. 185–193.

- ↑ Andrew Ramage, "Make Do and Mend" in Archaic Sardis. Caring for broken pots. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): Love for Lydia. A Sardis Anniversary Volume Presented to Crawford H. Greenewalt, Jr. Cambridge, London 2008 (Report / Archaeological Exploration of Sardis, Vol. 4), pp. 79-85; Nicholas Cahill: Lydian Houses, Domestic Assemblages, and Household Size. In: David C. Hopkins: Across the Anatolian Plateau. Readings in the Archeology of Ancient Turkey. Boston 2002 (The Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research, Vol. 57), pp. 178-179.

- ↑ Crawford H. Greenewalt, Jr .: Bon Appetit! In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, pp. 125-133.

- ↑ Ludwig Bürchner, Gerhard Deeters, Josef Keil: Lydia. In: RE. XIII 2 (1927) col. 2122-2202.

- ↑ Cf. Christian Marek: History of Asia Minor in Antiquity. Munich 2010 (2nd edition), p. 157); Hans Kaletsch: Lydia. In: DNP. 7 (1999), col. 544.

- ↑ Tanja Scheer, Martin Lindner (ed.): Temple prostitution in antiquity. Facts and fictions. Verlag Antike, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-938032-26-8 . (Oikumene. Studies on ancient world history. Volume 6)

- ↑ Athenaeus, Deiphosophistae 12,515df

- ↑ John Griffiths Pedley: Sardis in the Age of Croesus. Norman 1968 (The Centers of Civilization Series), VI. The City and Its Citizens, pp. 134-135.

- ↑ George Devereux: Xanthos and the Problem of Female Eunuchs in Lydia. In: Rheinisches Museum für Philologie. 124: 102-107 (1981).

- ↑ Against: Maciej Popko: Peoples and Languages of Old Anatolia. Wiesbaden 2008, pp. 109–110 (3. Anatolian peoples and languages, 3.2. In the 1st millennium B.C.E., 3.2.5. Lyder); For this: H. Craig Melchert: Lydian Language and Inscriptions. In: Nicholas D. Cahill (Ed.): The Lydians and their World. Istanbul 2010, p. 269.

- ^ Roberto Gusmani: Lydian Dictionary. With grammatical sketch and collection of inscriptions. Heidelberg 1964, pp. 17-22.