Female genital mutilation

Female genital mutilation ( English female genital mutilation , in short FGM ), female circumcision (English female genital cutting , short FGC ) or female genital mutilation refers to the partial or complete removal or damage of the external female genitalia . These practices are mostly based on traditionjustified out. The main distribution areas documented by studies are western and north-eastern Africa as well as Yemen, Iraq, Indonesia and Malaysia. Because the topic is taboo in society, it can be assumed that it will be used much more widely. It is estimated that there are around 200 million circumcised girls and women worldwide and around three million girls, mostly under the age of 15, suffer genital mutilation each year.

FGM / FGC is performed on girls from infancy, in most cases before onset or during puberty . Without medical justification and for the most part under unsanitary conditions, without anesthesia and by non-medically trained personnel, it is often used with razor blades, broken glass, etc. Ä. Performed. It is usually associated with severe pain, can cause serious physical and psychological damage and often leads to death.

FGM / FGC has long been criticized by women's, children's and human rights organizations in many countries. Both international governmental organizations such as the United Nations , UNICEF , UNIFEM and the World Health Organization (WHO) and non-governmental organizations such as Amnesty International , Terre des Femmes or Plan International call against female genital circumcision and they classify as a violation of the human right to physical integrity one on which is to be raised with the International Day Against Female Genital Mutilation , which has been held annually on February 6th since 2003.

On the African continent, non-governmental initiatives have been working in all affected countries to end the practice of mutilation since the beginning of the 1980s, understanding genital mutilation as a violation of children's rights and violence against children and women. The largest network is the Inter-African Committee on Traditional Practices with 34 national committees in 30 African countries and 17 international partner committees in Europe, Canada, Japan, the USA and New Zealand.

The practice is worldwide in most states - including all states of the European Union - a criminal offense . Nevertheless, in many of these countries, including Germany, girls are increasingly threatened as a result of increased immigration . Terre des Femmes assumed that there were more than 13,000 girls in Germany in July 2017, that is 4,000 more than a year earlier, who are at risk of genital mutilation. It is estimated that up to 8,000 women are affected in Austria, and there are around half a million victims across Europe; most of them in France.

terminology

So far there is no consensus on a uniform terminology for the practices. The view of the practices as purely local and cultural customs has changed due to their assessment as human rights violations and is therefore viewed and discussed as a global problem. This was accompanied by a change in terminology, which is currently being discussed.

History of terminology

In the English-speaking linguistic area was female circumcision (German: Female genital cutting ) the dominant collective name . The so-called practices were known outside of their range before 1976 mainly among medical experts and anthropologists . However, the term circumcision is also used to denote male circumcision ( circumcision ). Its application to practices in which the external female sexual organs are wholly or partially removed or damaged has come under fire because circumcision does not do justice to the physical and psychological effects of the practices.

For the first time in 1974, as part of a campaign, supported by a network of women's and human rights organizations , the term now Genital Mutilation (Engl. Genital mutilation ) introduced into the public debate about circumcision practices of female genitalia. By renaming the practices the activist network broke the semantic connection to male circumcision ( male circumcision ), which is considered as personal medical, religious or cultural reasoned decision on. The renaming implied a semantic proximity to castration and explained the practices on a subject of " violence against women " and human rights violations . Early 1980 spread the term "female genital mutilation" (English. Female genital mutilation ) in public, the media and the international literature.

Female Genital Mutilation was adopted in 1990 by the Inter-African Committee on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children (IAC) as a term for all African and international partner committees. At its sixth General Assembly in April 2005, the IAC in Mali published the “Bamako Declaration on the Terminology FGM”. The IAC criticized the use of the collective term Female Genital Cutting (FGC) by some UN organizations, which had been influenced by "special lobby groups", mainly from Western countries. The members of the IAC see the use of alternative designations - "Female Circumcision", "Female Genital Alteration", "Female Genital Excision", "Female Genital Surgery" and "Female Genital Cutting" - a politically motivated departure from the language rule " Female Genital Mutilation ”, which clearly takes a stand. They reaffirmed the demand to keep the term “Female Genital Mutilation” (FGM).

In 1991 the World Health Organization recommended that the United Nations adopt the term Female Genital Mutilation . The use of "mutilation" ( " mutilation ") underlines the fact that the practice is a violation of the rights of girls and women was. In this way, such a designation supports efforts to abolish it at national and international level. The term female genital mutilation replaced circumcision of female genitals as the more common name up until then and became the standard term in medical literature. For example, the use Bundesärztekammer the term female genital mutilation , the World Medical Association and the American Medical Association to use the English equivalent Female Genital Mutilation .

In the 1990s, parallel to the term FGM, the term "female genital cutting" (FGC) developed in the USA, a term that is seen as a more neutral term, especially when dealing with those affected. As a compromise, the term Female Genital Mutilation / Cutting - FGM / C for short - has become established in the English-speaking world .

The Germany-based women's rights organization Terre des Femmes has decided to use the term female genital mutilation in public relations . In a statement, however, she recommends using the term circumcision when dealing with those affected . In this context, circumcision is not a trivialization, but takes “the dignity of those affected in Germany” into consideration. This recommendation is also represented by the German Medical Association and the German Society for Gynecology and Obstetrics .

The compromise designation FGM / C , established in the English language, is used by the Children's Fund (UNICEF) and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) to capture the meaning of the term mutilation at the political level while offering less judgmental terminology for the practicing communities.

Discussions about the terms

The term female circumcision or circumcision is rejected by the World Health Organization, among other things, because it suggests a comparison with the circumcision of men . Circumcision is considered by many experts to be trivializing euphemism considered and misleading because in practice part of the clitoris or the entire clitoris and, in the case of infibulation, the entire external genital is removed and therefore to more far-reaching interventions than the distance the foreskin in men.

The term Female Genital Mutilation or FGM is among others from the United States Agency for International Development criticized (USAID), since on the one hand, ignoring the cultural background of the practices and on the other hand can lead to sufferers as "mutilated" stigmatizing . People who associate abolitionist efforts with the colonial era could also perceive the designation FGM as derogatory and / or see it as an indication of cultural imperialism . Surveys have shown that those affected often do not refer to themselves as "genital mutilated", but rather as circumcised women and see "mutilation" as insulting and hurtful.

In the United States, the term female genital cutting (FGC) has emerged in the course of various debates . USAID decided in 2000 to use this term, which it received as a more neutral one. In its literal translation - “female genital cutting” - this term cannot be precisely translated into German. In addition, in general German usage, “Cutting” as well as “Circumcision” is rendered with circumcision. According to Fana Asefaw and Daniela Hrzán, the use of the English name FGC indicates that this is a new research paradigm that is characterized by a critically reflective and anti- racist approach to the topic, which also critically questions FGC practices in western culture . This paradigm shift is not reflected in the German term "female genital cutting".

Depending on the context, the various terms are used side by side by several actors. This corresponds to an accepted procedure and represents the concern to contain FGM practices as much as possible.

The PR Researchers Ian Somerville wrote in 2011 that both female circumcision and female genital mutilation produce a particular linguistic framework that influences the perception of the practices. With the term female genital mutilation , the discourse had shifted to the point that it was now about questions of violence against women and thus about human rights.

According to anthropology professor Christine Walley, both the term circumcision and the term mutilation are problematic. Circumcision suggests relativistic tolerance, while mutilation gives the impression of moral indignation. The concept of mutilation also carries an at least implicit assumption that the parents and other relatives of those affected are something like child abuse . According to other authors, this allegation is highly problematic for many Africans, even those working to end female genital cutting traditions. Walley, who for her part uses the term female genital operations , further criticizes that the term female genital mutilation overly generalizes the various forms of this practice in a monolithic sense regardless of the geographies, meanings, religions and politics involved and women who would advocate these practices of their own accord, would generally vilify them in the context of an excessive western-oriented feminism.

to form

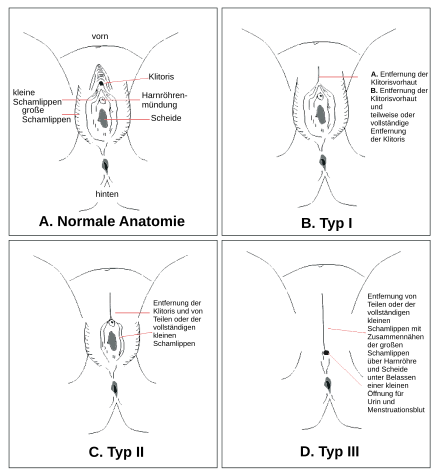

The World Health Organization (WHO) presented in 1995 before a classification to distinguish between different types of female genital mutilation, in a joint statement by WHO, in 1997 , UNICEF and UNFPA was acquired. This classification was revised in 2008 and has since been supported by other organizations and programs of the United Nations, in addition to those already mentioned by OHCHR , UNAIDS , UNDP , UNECA , UNESCO , UNHCR and UNIFEM . The classification serves as a basis for understanding the subject of research in research and is intended to ensure the comparability of data collections. Such a grid always requires a simplification; in fact there are many variants that combine different interventions. Even within a region or ethnic group, there can be significant differences in the form of circumcision.

A Normal anatomy

B Clitoral hood and, if applicable, the clitoris were removed

C Clitoral hood and, if applicable, the clitoris and the inner labia were removed

D Clitoral hood and clitoris and the labia were removed and the vaginal opening was partially sewn shut

According to this, the following four types can be distinguished according to the extent of the change:

- Type I: partial or complete removal of the externally visible part of the clitoris ( clitoridectomy ) and / or the clitoral hood ( clitoral hood reduction ) .

- Type Ia: Removal of the clitoral hood

- Type Ib: Removal of the clitoral hood and glans

- Type II: partial or complete removal of the externally visible part of the clitoris and the inner labia with or without circumcision of the outer labia ( excision ) .

- Type IIa: removal of the labia minora

- Type IIb: removal of the labia minora and complete or partial removal of the glans of the clitoris

- Type IIc: removal of the small and large labia and all or part of the glans of the clitoris

- Type III (also infibulation ): Narrowing of the vaginal opening with the formation of a covering seal by cutting open the inner and / or outer labia and joining them together, with or without removing the externally visible part of the clitoris.

- Type IIIa: Covering by cutting open and joining the labia minora

- Type IIIb: Covering by cutting open and joining the large labia

- Type IV: This category covers all practices that cannot be assigned to one of the other three categories. The WHO gives examples of piercing , cutting (introcision) , scraping as well as the cauterization of genital tissue, burning out the clitoris or introducing corrosive substances into the vagina.

The various ritual interventions, which are summarized in the fourth category, differ widely in terms of their backgrounds and consequences and, overall, have been less researched than those of the other three types. Some practices, such as cosmetic operations in the genital area or restoration of the hymen, which are legalized in many countries and are not generally classified as genital mutilation, can also be subsumed under this classification. From the point of view of the WHO, it is considered important to give the definition of female genital mutilation broadly in order to close gaps that could justify the continuation of the practice.

The proportion of different types of intervention to one another could only be estimated so far. The largest amount of data is available on circumcised African girls and women older than 15 years. These show about 90 percent genital changes of types I, II and IV, and 10 percent of type III. Other estimates looked at girls younger than 16 years of age and found a higher proportion of the most serious type III circumcisions in this age group. It is believed that up to 20% of all circumcised girls had type III changes.

The most invasive practice is type III infibulation , also known as pharaonic circumcision . The girl's legs are tied together from the waist to the ankles for up to 40 days to allow the wound to heal. The skin over the vaginal opening and the exit of the urethra grows together and closes the vaginal vestibule . Just a small opening for urine, menstrual blood and vaginal secretions to escape is created by inserting a thin twig or rock salt into the wound. This disability creates additional pain and risk of infection. Further health risks and complications arise from the fact that the vulva has to be cut open again (medical term: defibulation ) in order to enable sexual intercourse. If the man fails to open the vagina through penetration, the infibulated vaginal opening must be widened with a sharp object. An additional, more extensive defibulation is often necessary for delivery . Uncircumcised pregnant women are sometimes given infibulation before delivery because it is believed that contact with the clitoris leads to miscarriage. In some areas, the birth is followed by renewed infibulation, reinfibulation or refibulation .

history

Ancient and Middle Ages

The origins of female genital circumcision could not be clearly determined in time or geography. Even in antiquity, scholars dealt with the topic of circumcision, which at that time was mainly known from ancient Egypt. Descriptions can be found in Galenus , Ambrosius of Milan and Aetius of Amida . On a papyrus from 163 BC. The circumcision of girls is mentioned in BC, the epoch of ancient Egypt . Mummies have also been found showing signs of circumcision. Male circumcision can also be dated back to this time. According to the Greek historian Strabo , circumcision was carried out on both sexes in Egypt, and Philo of Alexandria , who lived around the time of Christ, reports that "among the Jews only men, with the Egyptians, men and women are circumcised". The ancient authors assumed that women were circumcised for aesthetic reasons in order to correct or improve the appearance of the female genitals.

It is believed that circumcision spread from ancient Egypt across the African continent. The routes of distribution and their time course cannot be clearly reconstructed.

In the Middle Ages, descriptions of circumcision can be found in the Canon medicinae of Avicenna (980-1037) and Abulcasis (936-1013), although this was recommended for excessively pronounced genitals.

Modern Europe and North America

The European confrontation with the practice began at the time of colonialism in the late 19th century. It was at this time that the first descriptions appeared in early ethnography. The distinction between “clitoral” and “vaginal” orgasm proposed by Sigmund Freud resulted in a disdain for “clitoral sexuality”. According to Freud, clitoral sexuality had to be overcome in order to attain mature sexuality. The psychoanalyst Marie Bonaparte criticized Freud's idea of the necessary detachment of the clitoris as an erogenous guiding zone. In 1935 there was a meeting between the future Prime Minister of Kenya, Jomo Kenyatta , the anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski and Marie Bonaparte. Through Malinowski she learned about female genital mutilation in Africa. With the support of Kenyatta, Bonaparte carried out field studies in East Africa in the following years , which dealt with the circumstances of circumcision and the consequences for women and represent the first scientific studies on the subject.

During the 16th, 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, and through the 1970s, clitoridectomies and other surgical procedures such as cauterization and infibulation were performed on female genitalia in Europe and North America . This was done in order to "cure" supposed female "ailments" such as hysteria , nervousness , nymphomania , masturbation and other forms of so-called female deviance . The English gynecologist Isaac Baker Brown propagated clitoridectomy as a treatment method in 1866 in his work on the "curability of various forms of insanity , epilepsy , catalepsy and hysteria in women" . It was well known that the female libido could be irreversibly damaged by such interventions. In 1923 Maria Pütz wrote in her dissertation :

"In three of me specially by Professor Dr. In cases kindly left to Cramer, after removal of the clitoris and partial or complete excision of the small labia, complete healing occurred . Masturbation was no longer practiced, and even after several months of observation the condition remained unchanged. Despite these encouraging results, the Clitoridektomie in masturbation there are now a great many cases in which the disease can not be influenced by any surgical procedures [...] A second throw of the opponents is that by reducing the libido also design option would be lifted. This objection is also unjustified; for it is clear that frigid women who only perceive coitus as a burden and who do not enjoy sexual satisfaction nevertheless conceive and give birth to healthy children. "

Geographical distribution

According to estimates by the World Health Organization on the prevalence of types I – IV of the WHO classification, more than 200 million women and girls around the world have had their genitals circumcised (as of 2013); around three million girls worldwide are threatened by FGM every year.

Africa

|

The main distribution areas are 28 states in western and northeastern Africa. In seven countries - in Djibouti , Egypt , Guinea , Mali , Sierra Leone , Somalia and in northern Sudan - the practice is widespread almost everywhere: over 90% of women between the ages of 15 and 49 are circumcised there. Infibulation (type III) is particularly widespread in Djibouti, Eritrea , Ethiopia , Somalia and Northern Sudan; more than half of the women in Djibouti and Northern Sudan and around 80% of women in Somalia are affected by this procedure.

The figures relate to certain countries because the data collection takes place within national borders. However, there can be considerable differences between individual regions of these countries. The ethnic affiliation is the main determining factor for the spread within border of often borders regions as well as the prevailing type of circumcision.

Asia

Outside Africa, Yemen is so far the only country with circumcision practice for which the prevalence has been statistically recorded: 22.6 percent of 15 to 49 year old girls and women are affected. Evidence suggests that female genital cutting is present in Syria and western Iran . The practice is also for various ethnic groups in Iraq , for northern Saudi Arabia and southern Jordan , for Bedouins in Israel , for the United Arab Emirates , for Muslim groups in Malaysia and for Indonesia (primarily on the islands of Sumatra , Java , Sulawesi , Madura , predominantly type I and IV). Circumcision is also documented for the Muslim Bohra in India . No data on the distribution are available for these countries.

Europe and North America

As a result of emigration from Africa in Europe and North America since the 1970s, the number of circumcised women and girls from regions of origin with circumcision rituals has increased. The estimates of how many migrant women were circumcised are relatively uncertain so far (as of 2008); In most cases, they are based on the compilation of data on the origin of migrant women with data on the statistical spread of circumcision practices in the regions of origin.

In 2005 there were around 60,000 women in Germany from countries where there is a tradition of circumcision; Non-governmental organizations believed up to 30,000 of them were affected or threatened. Terre des Femmes estimated in 2005 that at least 18,000 women in Germany are already affected and a further 5,000 to 6,000 girls are at risk. For Switzerland, UNICEF estimates the number of girls and women who are circumcised or at risk of being circumcised at around 6,700. In 2016, the number of affected women living in Germany was estimated at at least 47,000.

In 2006 the Austrian Federal Ministry for Health and Women carried out a study on genital mutilation together with the Medical Association and UNICEF. According to this, 14 percent of the resident gynecologists or paediatricians had treated a circumcised girl or woman at least once in their professional life. It was noticeable that the proportion outside the group of gynecologists was very low (only one pediatrician). Two doctors each in Vienna and in Styria stated that they had already been asked whether they would perform a genital cutting. 16 percent of the hospitals surveyed stated that they had treated girls or women who had been genitally mutilated. Three out of four patients are said to come from Somalia or Ethiopia. A visit was mainly made on the occasion of pregnancy or before delivery.

In the other European countries (as of 2008) there are only estimates for England and Wales, which are also based on data collected during gynecological examinations. According to these estimates, a total of around 66,000 migrant women were circumcised there; around 15,000 girls under the age of 15 were at risk of infibulation (type III) and another 5,000 girls were at risk of circumcision according to types I and II. There was circumcision tourism from France, where the intactness of the child's body is to be protected through mandatory screening in preschool and school, to England, where FGM has been banned since 1985, but tolerance ("ethnic sensitivity") towards this archaic tradition is greater is estimated.

It is also documented that some of the migrant women continue to practice circumcision in secret, despite legal prohibitions in the receiving countries. In France, Italy, Spain and Switzerland there were criminal trials in this connection. The interventions took place either in the host country or during a trip to a country of origin. There is no data collection on this phenomenon (as of 2008). See Legal Assessment . For the first time in US history, a criminal case under 18 USC 116 (female genital mutilation) began in April 2017 against a doctor named Jumana Nagarwala and a married couple (all members of the Shiite Dawudi Bohra ).

Australia

Female circumcision is traditionally found among some ethnic groups of the Aborigines , the Australian aborigines. Similar to the subincision in men, the operation took place as part of initiation rites. To what extent circumcision is currently practiced is unclear. While the UNHCHR claims in a working paper that the Pitta-Patta society in Queensland practices the IV incision , this view has been challenged by Australian scientists. Most of the circumcision practiced in Australia today is likely to occur within migrant populations from the African and Arab cultures.

Middle and South America

The phenomenon has been sporadically documented in America, for example for the Emberá -Chamí Indians in Colombia .

Criticism of dissemination statistics

Since data on FGM is only systematically recorded in a few African countries, dissemination statistics should be viewed with this reservation. It is also criticized that predominantly African FGM practices are included in the statistics. Asefaw & Hrzán argue that corrections to genitals in the context of cosmetic surgery, which for them also fall under the WHO definition of FGM, are not taken into account in statistics.

Affected demographics

In ethnic groups in which the circumcision of female genitals is a tradition, the vast majority of women are usually affected. The age of circumcision varies from group to group: some girls are circumcised in the first week of life, some not until puberty or when they get married. Most of the girls are between four and twelve years old at the time of the procedure. Often circumcision takes place at the beginning of puberty and is then part of an initiation rite that marks the transition to adulthood. Adult women sometimes undergo circumcision shortly before or after marriage. This is mostly due to the fact that the husband or mother-in-law does not consider the existing genital cutting to be sufficient.

The younger the girls are, the lower their level of knowledge on the one hand and the lower their chance of defending themselves against the intervention or even evading it on the other. According to UNICEF figures, female circumcision tends to find more support in rural African populations than in urban ones. The reason for this is the low access to schooling in rural areas, especially for women. This goes hand in hand with a stronger adherence to traditions and greater social control than in the big city. Social dependency and the lack of an economic perspective are therefore also the main factors that make it difficult to end the practices.

In contrast, social scientists - such as the anthropology professor and WHO employee Carla Makhlouf Obermeyer for the first time in 2003 - found in other studies that there were no differences in the frequency of implementation based on a different intellectual level. Only the way is different: In more educated circles the trend towards so-called medicalization, i.e. the implementation of circumcision in hospitals or by professional medical staff and under more hygienic conditions, can be observed. In general, over 90 percent of those affected hold on to the tradition and only about four percent do not want their own daughters to be circumcised. Some educated women choose to be circumcised in adulthood. However, extreme forms of circumcision (such as infibulation) are not chosen here.

Reasons for the practice of circumcision and mutilation

tradition

Tradition is believed to be the primary reason for this practice. Because circumcision has long been practiced on practically all women in the practicing group, they consider circumcision an integral part of their cultural world.

As L. Leonard reported in 1996 about the practice in Chad, circumcision (female circumcisionals) is celebrated as a solemn initiation rite in which a girl is the focus and is officially recognized as an adult woman. Circumcision was often accompanied by various rituals and instructions intended to impart the cultural knowledge of their community to the girl. Circumcision itself can therefore be seen as part of this transition to adulthood: the adolescent learns to endure pain and to be able to control their body. The presence of circumcision serves as a symbol that the woman has gone through this process, is an integral part of her culture and shares its values. According to SM James, female genital mutilation (James used the expression female circumcision / genital mutilation in 1998) symbolizes a new birth among the Kikuyu in Kenya, whereby the girl is not born as a child of her parents, but as a child of the entire tribe. The importance of circumcision as an initiation rite has declined significantly in recent years. Circumcision tends to be carried out at a younger age of the girl, especially in infancy, which is related to school attendance, increased education of young people and also to the prohibition of the practice in some countries. Younger girls have less knowledge about FGM and are accordingly less able to evade the practice or take legal action. According to Terre des Femmes, there are now an increasing number of clinics in Indonesia that offer delivery with FGM as part of a package right after the birth of a girl, including piercing the ears.

Social and economic reasons

Girls who are not circumcised run the risk of social exclusion. Circumcised genitals are considered a necessary requirement for marriage in the practicing communities. A study in Sudan found that, with increasing economic dependence on men, women are particularly careful to maintain their ability to marry and to please their husbands sexually and reproductively to prevent divorce. In times of economic uncertainty, parents very rarely risk leaving their daughters uncircumcised.

In a survey in Egypt, parents said that girls are spending increasing amounts of time to school and women are forced to work outside of the home due to economic conditions. Female genital cutting was seen as protection because accompaniment was not always possible. In addition, some parents stated that husbands have been migrant workers for many years and that circumcision protects women from dishonor by appeasing their sexual needs.

Medical myths

Sometimes there are dramatic, medically wrong ideas that connect certain problems with the uncircumcised condition.

In the event that circumcision is neglected, negative consequences for the health and fertility of the woman and also for the health of the sexual partner and the children born by her are assumed. According to these ideas, the clitoris is seen as an organ that can even kill the husband or child if it is touched during sexual intercourse or during childbirth. The supposed danger according exist in Egyptian terms such as "wasp", "sting" or "excess" to describe the clitoris.

There are also myths that female genitals can continue to grow without circumcision and that the clitoris can reach the size of a penis.

Aesthetic ideas

Because circumcision is an ancient tradition in the practicing communities, reduced or infibulated genitals are considered normal there. An uncircumcised vulva is therefore often viewed as unaesthetic. The reshaping of the genitals, according to a culturally shaped ideal of beauty, can be a reason for circumcision. The vulva should appear narrow and smooth, protruding skin areas are rated as unaesthetic. According to social and cultural scientist Kathy Davis, beautification, sublimity above shame, and the desire to conform are among the main motivations put forward by African women who advocate surgery on the female genitalia.

Regionally, there are different, traditionally anchored ideas: Some ethnic groups perceive the clitoris as a remnant of the male penis, so according to this idea, removing it strengthens the female aspects of women. Also protruding parts of the genitals such as the labia can be seen as unneeded, ugly remnants, the removal of which rounds off the body and thus makes it more beautiful and also more erotic.

- Sexual preferences - dry sex

So-called dry sex is particularly common in regions south of the Sahara . On the one hand, body fluids on or in the female genitals are perceived as repulsive and the noises and smells that occur during sexual intercourse are perceived as embarrassing due to the moisture. On the other hand, a swollen, dry vagina, which, due to its tightness, leads to additional friction during penetration even on a smaller penis, is said to increase the man's gain in pleasure. This preference in combination with the ideal of a rounded vulva closed by FGM leads to an increase in the entry possibilities for various infectious germs, including HIV , as injuries occur regularly in this way. A lack of lubrication due to the circumcised woman's limited sexual responsiveness or due to the practice of introducing astringent herbs or other substances into the vagina to dry it out, overrides the natural partial protection against infections in a supple, moist vaginal climate.

Suppression of female sexuality

Female genital mutilation can severely limit sexual desire and, among other things, make the affected woman unable to experience orgasm . Furthermore, it often makes sexual intercourse awkward and painful for women. The reduction of a woman's sexual response by removing the clitoris and labia minora are viewed positively in practicing cultures, as it is believed that the procedure reduces sexually active behavior that could harm family honor. In addition, infibulation is concrete evidence of virginity. Thus, circumcision can be viewed as a means of ensuring the woman's premarital virginity and her fidelity in marriage. With regard to the gender ratio, FGM tries to prevent a possible loss of control and power for the man, which can occur if he does not succeed in sexually satisfying his uncircumcised partner.

In the 1970s, feminist authors saw the control and suppression of female sexuality as an essential reason for female genital mutilation. A woman is reduced to her mere reproductive function.

This view has been questioned by some authors after some specialist publications since the 1990s had suggested a more differentiated approach. Proponents of the practice point out that female genital mutilation is usually practiced and demanded by women, while men in the practicing cultures often did not express a clear preference for circumcised women. From a psychoanalytical point of view, this phenomenon is attributed to the psychological trauma as a result of the intervention, which results in a lifelong attempt to avoid the pain stored in the pain memory . This results in development inhibitions u. a. regarding the ability to develop empathy . Loss of empathy due to psychological trauma usually occurs when one's own experience of suffering is inflicted on another person. In Somalia, for example, a majority of men and tribal elders are in favor of marrying a circumcised woman. They argue that circumcised women are less willful and easier to control, which Janna Graf attributes to the psychological trauma of women.

religion

A mention of female genital cutting was found in a Greek papyrus in Egypt, circa 163 BC. BC, found. The practices are thus older than Christianity and Islam. Yet it is often believed that this practice is rooted in Islam.

The religious communities that practice female genital cutting include primarily Muslims, but also Christians of various faiths, Ethiopian Jews and followers of traditional religions . In Sierra Leone, where 90 percent of all women are circumcised, mainly type II, circumcision is practiced by all Christian and Muslim ethnic groups with the exception of the Creoles . However, the practice goes back to pre-Christian and pre-Islamic times. In countries where female circumcision is common, uneducated believers in particular often assume that it is religiously prescribed. In Islam, depending on the interpretation, this is also the doctrinal opinion (see Occurrence in Islam ).

In general, there are religious leaders who speak out in favor of circumcision, those who don't speak out, and others who oppose it. A call by the Coptic Church in 2001 that circumcision was unchristian almost completely ended the practice among the Egyptian Copts. In Kenya , the traditionalist Mungiki group has become known in the media in connection with forced circumcision.

Occurrence in Islam

The Quran does not mention the circumcision of women or men. The Surah 95 , 4 reads: "We have indeed created man in the best form." It is used by hadithkritischen Muslims to mark the circumcision as fundamentally un-Islamic. Some minorities in Islam justify genital cutting by citing a few hadiths . However, this is often a certain form of intervention, the so-called "slight circumcision" ( Arabic الخفاض القليل, DMG al-ḫifāḍ al-qalīl ). With this type of circumcision, the externally visible part of the clitoral hood is removed. Few other scholars justified than chafd /خفض / ḫafḍ or chifad /خفاض / ḫifāḍ but also the partial amputation of the clitoris or even the clitoridectomy. More harmful forms such as infibulation are in no way legitimized by Islam, and there are no Islamic sources of law that mention circumcision of the small or large labia.

Sunni conception over the centuries

In Sunni Islam, attitudes towards female circumcision varied from permitted to prohibited . In some works of Islamic jurisprudence , such as in al-Fatawa l-Hindia , the circumcision of women is referred to as Sunnah or noble deed . However, female circumcision only found attention in countries where it was already rooted in pre-Islamic times. In other countries, opinions in favor of female circumcision have either been ignored or unknown to Muslims. Scholars who advocate female circumcision invoke inhibition of sexual needs rather than the canonical scriptures.

Circumcision is generally recommended for the Malikites , for the Hanafis as well as for some Hanbalites it is honorable (makruma), the Shafiites explicitly declare it to be a religious duty. The most frequently cited hadith in connection with the circumcision of women reproduces a discussion between Mohammed and Umm Habiba (or Umm ʿAtiyya) (the hadith of the circumciser). This woman was known as a circumciser of female slaves and was one of the women who immigrated with Mohammed. After discovering her, he is said to have asked her if she was still in her job. She is said to have answered in the affirmative and added: "On the condition that it is not forbidden and you do not tell me to stop". Mohammed is said to have replied: “But yes, it is allowed. Come closer so that I can teach you: When you cut, do not exaggerate (lā tunhikī) because it makes the face brighter (aschraq) and it is more pleasant (ahzā) for the husband ”. According to other traditions, Mohammed is said to have said: "Cut lightly and do not exaggerate (aschimmī wa-lā tunhikī) , because that is more pleasant (ahzā) for the woman and better ( aḥabb ) for the man". (Another translation: "Take away a little, but don't destroy it. That is better for the woman and is preferred by the man." - "Circumcision is a sunnah for men and makruma for women.") This hadith, however, is referred to as ḍaʿīf ( weak ) and is therefore probably not based on statements by Muhammad. Those who acknowledge this hadeeth interpret it differently. One view is that “is better for women and preferred by men” refers to “do not destroy”. Mohammed would then not have wanted to break with the pre-Islamic tradition, but himself preferred not to do so. Another interpretation assumes that it is a "Makruma", a voluntary, honorable act, the omission of which is not punished - in contrast to the Sunna , which is a custom that unites all Muslims and should be observed.

In 2008, al-Azhar University banned female circumcision .

execution

Executing persons

According to the studies analyzed as part of a review article from 2013, 52.7% of the interventions were performed by traditional obstetricians, 16% by doctors, 14% by older women, 6.1% by traditional healers, 5.8% by nursing staff , 2.1% done by barbers and 3.3% by family members. In the corresponding cultures, the profession of the circumciser is a respected activity that ensures a relatively high income for the circumciser's family. According to Melanie Bittner, it can be assumed that families with a higher socio-economic status will use medical staff for FGM more often. In addition, an urban milieu increases the chance of being informed about the dangers of FGM through health education projects and therefore, if at all, of having the intervention carried out by medically trained, which is legal in only a few countries.

Traditional techniques

|

|

|

|

Tool used by former circumcisers from East Africa

|

Left: Circumcision blade from Esperance, Southwest Australia (taken in the British Museum in 1905). Middle and right: Knife for circumcision from Groote Eylandt , Northern Australia (taken in 1925)

|

Traditional circumcisions take place outside of hospitals in unsanitary conditions. In the traditional way, those affected are usually not anesthetized and are in such severe pain that they have to be held by several adults. It is documented that bearing the pain is seen as an important part of the ceremony in preparation for the role of wife and mother in the society of Rendille . (Special) knives, razor blades, scissors or broken glass are used as tools. Often several girls are circumcised with the same tool, increasing the risk of infection and the risk of transmitting diseases, from infectious and venereal diseases to HIV. Wound closure are acacia thorns , string, sheep gut, horsehair , raffia or iron rings used. Substances such as ash, herbs, cold water, plant sap, leaves or wound compresses made from sugar cane are supposed to stop the heavy bleeding that usually occurs when the external female genital organs are circumcised.

Medicalization

The term “medicalization” refers to a range of modifications to the procedure that are intended to reduce some of the negative health effects of circumcision. The term is based on a western understanding of medicine. The proportion of circumcision that takes place under such conditions varies in different countries.

Medicalization can take place through many different modifications and range from small to very extensive changes. One possibility is to additionally train circumcisers, for example in female anatomy . Alternatively, the operation can be performed by obstetricians, medical assistants, or nurses who have undergone scientific medical training. The highest degree of medicalization would be carried out by doctors. Furthermore, hygienic conditions both at the place of implementation and with the instruments used are decisive for the degree of medicalization. The administration of antibiotics and tetanus injections can significantly reduce the health risk of the procedure. Local or general anesthesia can replace traditional means of pain relief. If complications arise, access to medical care can be offered.

Egypt , Djibouti and Sudan are considered countries with a high degree of medicalization of circumcision. In Egypt, where 47.5 percent of circumcisions are performed by doctors, this medicalization is concentrated in urban areas. Reasons for this are, in addition to the higher availability of access to doctors, the urban environment, which increases the chance of being informed about the dangers of circumcision through educational projects. If the resulting additional costs have to be covered by the families themselves, poorer women have less chance of medicalization than those from wealthier classes.

Research has shown that, especially with the lighter forms of circumcision, complications and deaths can be greatly reduced through medical training and more hygienic conditions. In a study in northern Kenya , for example, it was shown that preventive tetanus vaccinations and prophylactic administration of antibiotics, as well as instructions to use new sterile razor blades for the procedure, could reduce the risk of short-term consequences by 70 percent. By anesthesia circumcision for those affected will be less painful.

The medicalization of circumcision is controversial in terms of its political and humanitarian benefits.

Health consequences

The consequences depend on the type of circumcision, the conditions under which it is carried out and the general health of the girl or woman. Infibulation is particularly serious.

Acute complications

Acute complications are usually due to inadequate hygienic and technical conditions. This can lead to high blood loss ( hemorrhage ), which, if not breastfed, can lead to shock . Germs can lead to local and generalized infections (e.g. HIV infection ), injuries to neighboring organs and death. Poor wound suturing can lead to scarring. Problems that can arise immediately after circumcision are sepsis , stenosis and the formation of fistulas or cysts . Complications such as urinary tract infections and bladder emptying disorders ( dysuria ) can also occur. In Africa in particular, a clinical operating environment is rarely available, so that complications that can lead to death often occur here.

Long term consequences

Restriction of sexual sensation

The clitoris has a high density of nerve endings and is therefore particularly sensitive to touch and receptive to sexual stimuli. The removal of sensitive clitoral tissue can lead to reduced sexual stimulability and the ability to experience an orgasm is accordingly restricted . The entire clitoris, however, is larger than the visible part and consists for the most part of structures that are covered by the outer labia.

The main negative effects on sex life were infibulation (type III circumcision). With a type III circumcision, the narrowing of the vaginal vestibule and scarring can lead to pain during vaginal intercourse , a so-called dyspareunia , or the possibility of penetration may be limited. A survey of 300 infibulated Sudanese women and 100 Sudanese men showed that it can take between three and four days, but also up to a few months, for the narrowed vaginal vestibule to dilate so that sexual intercourse can take place normally. In about 15 percent, widening through penetration does not succeed in the long term, so the couple (usually secretly) has to use an obstetrician to help. However, in recent decades it has become more and more fashionable in Sudan for women to have their vaginal vestibules narrowed again by sewing after giving birth. This has to do with the fact that the woman then appears virginal again. Some women also reported that if their vaginal vestibule is narrowed, their residual genitals are the most likely to experience pleasure.

The undistorted scientific recording of the effects of various circumcisions on sexuality is opposed by the fact that data in this regard can only be obtained from surveys. In the affected regions in particular, however, interviewing women is difficult because, for cultural reasons, they are not particularly inclined to speak openly with strangers about their sexual feelings and problems. Thus, many studies are based on the statements of a few test subjects, whose representativeness is questionable. The question of comparability is also pending: since the procedure often takes place before puberty, the majority of women affected only know sexuality from the perspective of the circumcised state. Furthermore, the assessment of both pain and sexual pleasure is influenced by the cultural background, the transfer of Western concepts is not easily possible. Accordingly, the studies on this topic come to very different results.

The social psychologist Hanny Lightfoot-Klein suspects that the physiological functions of infibulated women are damaged or severely reduced, but not abolished. This can be compensated for perceptually physiologically to a certain extent . The decisive factor is the fact that almost all of the women surveyed do not know uncircumcised sexuality and that many of the women surveyed live in a harmonious relationship. Many infibulated women would report that they can experience pleasure and even an orgasm. Others reported that as a result of pharaonic circumcision (infibulation) they could not feel the man.

A survey at the Research Center for Preventing and Curing Complications of FGM / C in Italy comes to a similar result . A total of 137 women who had been affected by various forms of genital mutilation took part in the study. 91 percent of the infibulated women stated in a structured interview that they perceive sex as pleasurable, and 8.57 percent regularly experienced orgasm. Of the group of women with lighter forms of circumcision, 86 percent said they found sex pleasurable, and 69.23 percent regularly experienced orgasm. The authors emphasize that even in infibulated women, at least rudimentary erogenous zones remained. If necessary, sexual therapy should be used to ensure that infibulated women who have not yet been able to experience orgasm learn this ability by changing their perception. According to this survey, the negative perception of FGM by Western women and men is not beneficial for individual female emigrants living in Europe, as this can lead to a negative attitude towards one's own body and its ability to orgasm.

A study conducted in the Edo region of Nigeria comparing 1,836 circumcised women with an uncircumcised control group found no significant differences between circumcised and uncircumcised women in the frequency of sexual intercourse, the experience of sexual arousal, and the frequency of orgasm. 71 percent of the circumcised women were circumcised according to type I, 24 percent according to type II, so there were predominantly milder forms of circumcision. The finding that the ability to orgasm in circumcised women is comparable to that of uncircumcised women could be due to the fact that the clitoris extends deep into the body and, depending on the procedure, only the outer part is removed. The psychologist Gillian Einstein speculates that after the circumcision a neurobiological restructuring takes place through processes of neuronal plasticity : the excitation function of the removed tissue is taken over by the surrounding structures.

In contrast, a study at the Maternal and Childhood Centers in Egypt showed that female genital mutilation has a negative impact on the psychosexual life of the women concerned. 250 patients from the clinics were randomly selected, interviewed and gynecologically examined; 80% of them were circumcised. The patients with FGM reported significantly more often dysmenorrhea (80.5%), dryness of the vagina during intercourse (48.5%), lack of sexual desire (45%), less initiative during sex (11%), less pleasure during sex Sex (49%), fewer orgasms (39%), and difficulty reaching orgasms (60.5%) than uncircumcised women. However, other psychosexual problems such as dyspareunia and loss of interest in foreplay did not achieve statistical significance . Another Egyptian study found that those affected with FGM type II and type III (removal of the clitoris and inner labia) had a significantly reduced ability to orgasm and reported significantly less sexual arousal and desire than the control group. Those affected with FGM type I (removal of the clitoral hood and frenulum) had lower scores than uncircumcised women, but these results were not significant. A connection between FGM and restricted sexual functions was also found in a study in which 130 Saudi Arabian women with FGM and 130 uncircumcised women took part. The women completed an Arabic translation of the Female Sexual Function Index and the scores for the two groups were compared. Women with FGM had significantly lower scores in the categories arousal, lubrication , orgasm, satisfaction and overall results. Only in the pain category were there no significant differences.

A systematic review and meta-analysis published in 2012 of 15 studies with a total of 12,671 participants from seven countries showed that circumcised women report more often about dyspareunia, the absence of sexual desire and less sexual satisfaction than women without FGM.

Birth complications

A study published by the World Health Organization in 2006, in which 28,393 pregnant women from six African countries took part, found connections between the degree of circumcision and the occurrence of complications during childbirth. For the study, data on caesarean sections , blood loss, length of hospital stay as well as birth weight, child and maternal mortality and the condition of children immediately after birth ("resuscitation rate") were collected. There were differences in all variables except for birth weight. The risk tended to be higher for circumcised compared to uncircumcised women. A significant deviation, however, was often only found for type II and type III circumcised women, while type I circumcised women did not differ significantly from uncircumcised women.

A connection between FGM and negative maternal-fetal effects was found in a study published in 2011. 4800 pregnant women, 38% of them with various types of FGM, were examined over a period of four years. The duration of hospitalization was longer for women with FGM than for women without FGM. Delayed births, caesarean sections, postnatal bleeding, early neonatal deaths, and hepatitis C infections were also more common in circumcised women .

In a further study in which 68 circumcised first-time immigrants from East Africa were compared with 2,486 uncircumcised Swedes, a Swedish university hospital with good obstetric care showed that circumcised women from Africa had a time advantage in the process of giving birth: the riskiest phase of childbirth , the expulsion phase , was 40% shorter (on average 35 minutes compared to 53 minutes for uncircumcised women) and long expulsion phases with an increased risk for the unborn child (more than 60 minutes) were five times as frequent among uncircumcised Swedes as among immigrants.

infertility

In a study of around 280 women who were examined at two hospitals in Khartoum in 2003 and 2004 , 99 were found to be sterile. These were compared with a control group of 180 women who were pregnant for the first time. There was an almost significantly increased risk for circumcised women of being infertile, with the anatomical extent of the mutilation being decisive for an influence on fertility. The finding contradicts the belief of many in practicing countries that genital mutilation promotes fertility in women.

Other health consequences

With infibulations, the narrowing of the vaginal opening often leads to a congestion of the menstrual blood, which (like the urine) can only flow out slowly and in drops. Such menstrual cramps lead to a potentiation of the tendency to infection, since menstrual blood and urine can accumulate for hours or days and thus the pH value of the vagina can shift to the alkaline, whereby infections are favored. Infibulated women thus represent a risk group and therefore require special attention in health care.

A study conducted on a Nigerian sample found that circumcised women were significantly more likely to suffer from abdominal pain, reproductive tract infections, and genital ulcers , and were more likely to report yellow vaginal secretions, than an uncircumcised control group .

A study of 5337 circumcised women in Mali and 1920 people in Burkina Faso showed that FGM is associated with a number of long-term complications. In contrast to most other studies that rely on self-assessments by individuals, this study used observations from healthcare professionals. Thereafter, the likelihood of complications increases with the extent of the mutilation. Many of the complications, such as keloids , bleeding, and vaginal thickening, are due to the scarring caused by the mutilation. Circumcised women also have a significantly higher risk of tearing the perineum during delivery because the tissue has lost its elasticity due to the scarring. FGM is also related to symptoms that suggest genital infections.

Whether and in what way circumcision can influence the transmission of sexually transmitted diseases is controversial. While some studies found increased HIV rates among circumcised women, other studies found no association or even reduced infection rates. Demographic or behavioral factors can also act as moderating factors to explain complex relationships.

In 2005, UNICEF , the women's rights organization Terre des Femmes and the German Professional Association of Gynecologists (BVF) organized a survey among gynecologists on the situation of circumcised girls and women in Germany. For this purpose, a questionnaire was attached to the association magazine “Frauenarzt” in the January 2005 issue and invited to participate. 493 responses were received, which corresponds to a response rate of 3.73 percent. The survey showed, among other things, that around 15 percent of the circumcised patients of those gynecologists who took part in the survey complained of chronic pain.

Surgical reconstruction

With the methods of plastic surgery , the consequences of circumcision can be partially reversed. Structures that were previously removed, such as the external part of the clitoris or the labia, are re-modeled from existing tissue. The goal of clitoral reconstruction is to remove the painful and insensitive scar tissue that has formed after circumcision and to expose uncarried clitoral structures. A new clitoral glans (“Neoglans”) is formed from this. A cohort study examined the development of 866 circumcised women who underwent reconstructive surgery between 1998 and 2009. Most women reported decreased discomfort and improvements in sexual sensation one year after reconstruction. Deinfibulation - i.e. the reverse operation of an infibulation - can result in new psychosocial burdens for the woman. The gynecologist Sabine Müller explained this to Deutschlandfunk :

“Of course you can always offer de-infibulation, the opening of the vagina, but you have to give very good advice beforehand about what will happen; for example this woman will have a urine stream again. This could be very uncomfortable and stigmatize for you, because: Your relatives and friends do not have a urine stream. For example, if you went to two toilets next to each other, in a public area, and then one could hear the other, and then the woman whose urine stream you can hear would be infinitely ashamed. For many women, this is a very strong motivation not to let them do it. "

Awareness campaigns and efforts to eliminate them

As early as the early 20th century, colonial administrations tried to combat female circumcision as a pagan ritual , although the approach depended on the respective colonial power. For example, while the French colonial administration tolerated circumcision, the British fought against it early on, in Kenya since the 1930s and in Sudan since the 1940s. Anthropological reports from the colonies have existed since then, but for a long time the topic played practically no role in the consciousness of the European public. In the course of the women's movement, which gained strength in the 1970s and as a result of the sexual liberation of the 1960s, the view of female sexuality and the female orgasm changed. The importance of the clitoris was increasingly emphasized in relation to the vagina, and sexual pleasure was emphasized in relation to the reproductive function of sexuality. With the increasing emphasis on the importance of the clitoris for female sexuality, it became a political symbol, a “ metaphor for the self-determination of women”. The practice, which until then had been regarded as exotic and marginal, now became a central concern of feminism ; Understood as a frontal attack on female sexuality, female circumcision became the epitome of patriarchy and oppression. A broader public became aware of the issue in 1994 through a report by feminist Fran P. Hosken - later known as the "Hosken Report" -. The previous almost complete disregard was followed by extensive and sometimes strongly emotional reporting in the media as well as numerous books (for example, the autobiography Desert Flower by Waris Dirie 1998) that condemned female circumcision. As a result of the reporting - and in turn intensifying it - activism began to act against the practice , which was initially supported by women's and human rights groups as well as smaller NGOs . Politicians increasingly took up the issue, large supranational organizations such as the WHO or the UN advocated the fight against female circumcision, and in most western countries circumcision was sometimes made subject to severe punishment. On an initiative of the non-governmental organization Inter-African Committee on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children (IAC) from 2003 , February 6th was declared the "International Zero Tolerance Day Against Mutilation of Female Genitalia" in order to draw attention to the topic regularly and worldwide to make and to promote the abolition of the practices.

In the meantime, almost all active parties in the western cultural area have taken a negative stance on female genital mutilation and are in favor of its abolition. The points of criticism made include:

- the negative health consequences for the women affected as well as increased infant mortality at birth;

- the various psychosomatic consequential damages, e.g. B. Post Traumatic Stress Disorder;

- unsanitary and medically irresponsible approach during the mutilation with increased risk of infection and bleeding up to and including death;

- the oppression of women through sexual control, i.e. the restriction of their ability to experience sexual pleasure;

- generally a violation of human dignity and the right to physical integrity by a medically necessary intervention without the consent ( informed consent ) of those affected.

Waris Dirie, who acted as a UN special envoy against the circumcision of female genitals between 1997 and 2003 , completely rejects justifications based on culture , tradition or religion . She describes the practice of circumcision as genital mutilation ("female genital mutilation"), torture ("torture") and crime ("crime").

International organizations such as UNICEF and the World Health Organization have been striving for the complete abolition of female genital cutting since the 1990s. Numerous local organizations and initiatives in countries with a tradition of circumcision, as well as school authorities, are also working towards this goal, mainly by informing not only practitioners but also the population about the negative effects of circumcision. This has led to various ethnic groups and village communities declaring the practice to be abolished. Female genital cutting has also been banned by law in a number of African countries; however, the implementation of these bans varies from country to country and is often incomplete.

Another approach is to create alternative career opportunities for traditional circumcisers. However, despite such programs, some circumcisers return to their previous occupation because it is highly regarded, well paid and still in demand.

On December 20, 2012, the UN General Assembly unanimously passed a resolution calling on member states to step up their efforts for a complete end to female genital mutilation.

Prohibition by means of Islamic legal opinions

Several initiatives try to outlaw the practice of female and female circumcision by means of Islamic legal opinions ( fatwas ). For example, on November 22 and 23, 2006 , Rüdiger Nehberg initiated an international conference of Islamic scholars at al-Azhar University in Cairo. The scholars decided that female genital cutting was inconsistent with the teaching of Islam:

"The genital cutting of women is an inherited bad habit (...) without a basis in the Koran or an authentic tradition of the Prophet (...). Therefore, the practices must be stopped based on one of the highest values of Islam, namely not to be allowed to harm people without cause (...). Rather, this is viewed as a criminal aggression against the human race (...). The legislative organs are called upon to declare this cruel bad habit as a crime. "

In individual cases, however, the decision about circumcision should be left to the doctors. The association TARGET e. V von Rüdiger Nehberg has summarized the results of the conference in the book Das goldene Buch . This is intended to inform prayer leaders and religious leaders and to encourage them not to approve of the circumcision of the female genitalia.

In 2005, Islamic scholars in Somalia - where infibulation is practiced almost everywhere - published a fatwa directed against circumcision of girls. In March 2009, Nehberg and Tarafa Baghajati visited the Qatar- based Islamic legal scholar Yusuf al-Qaradawi , who is considered the most important contemporary authority on Sunni Islam. In a fatwa drawn up by the legal scholar, the genital mutilation of girls is described as the “work of the devil” and is forbidden because it is directed against the ethics of Islam.

Group psychotherapy approach according to Möller / Deserno

Based on the thesis that initiation rituals have both a conflict-avoiding function in the context of the social structure and a restrictive or destructive effect with regard to individuality and subjectivity, according to Möller and Deserno , psychoanalysts and professor of psychology, projects should to eliminate female genital cutting, address the parameters of conflict avoidance and individual restriction / destruction. In addition to extensive accompanying research on the previous projects themselves and evaluation of how circumcision is processed psychologically, discussion groups should be initiated by women and men in order to initiate a joint discussion of female genital mutilation. The key point here is the gender relationship, in which the mutually dependent dimensions of production, institution such as tribal order or religion and intergenerational relationship and the genital mutilation anchored in them become clear. This reflection is intended to help make the gender ratio, which the authors consider unequal, negotiable. As an orientation for the design of the groups, the concept developed by Dan Bar-On for overcoming the Middle East conflict between Israelis and Palestinians is recommended.

Effects

According to UNICEF figures, in 14 of 15 countries surveyed, the proportion of 15 to 49-year-old women surveyed who support the continuation of circumcision is lower than the proportion of those who are themselves circumcised. Especially in Burkina Faso - where the state has made efforts to abolish it - the proportion of women who support circumcision (17%) is significantly lower than the proportion of those who are circumcised (77%). Only in Niger are more women (9%) in favor of circumcision than are affected by it themselves (5%). However, non-approval / rejection of the practice does not always mean that the women concerned actually do not have their daughters circumcised.

Another study found that in nine out of 16 countries ( Ethiopia , Benin , Burkina Faso, Eritrea , Kenya , Yemen , Nigeria , Tanzania and Central African Republic ), the proportion of circumcised women in younger age groups (15-25 year olds) is lower than in older ones Women, indicating a decline in practice; in the remaining seven countries ( Egypt , Ivory Coast , Guinea , Mali , Mauritania and Sudan ) there are hardly any differences by age group.

In Ethiopia, according to a study by local non-governmental organizations, the prevalence nationwide fell from 61% to 46% between 1997 and 2007. It decreased most in the regions of Tigray , Oromiyaa and in the south as well as in the urban regions of Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa , while in the regions of Somali and Afar - where infibulation is common - hardly any decrease can be observed. For 29 ethnic groups, 18 of them in the southern region, the decline is around 20%. In Togo , according to a study by the government and the UN, the circumcision rate fell by half between 1996 and 2008 and is now 7%.

In such studies, which are based on surveys, it should be noted, however, that respondents may make false statements and withhold circumcision, especially if they actually have to expect prosecution for this. The decline may therefore be less severe than surveys suggest.

The Senegalese village of Malicounda Bambara gained worldwide attention when the residents declared the abolition of circumcision in 1997. Since then, about 2,657 villages in Senegal, Guinea and Burkina Faso have made similar declarations. However, some residents of these villages are supposed to continue the practice.

Other research and data suggest that the elimination efforts contributed to medicalization , but not to the elimination of the practice. For example, the Maasai in Kenya - where circumcision takes the form of clitoridectomy as part of an annual ritual - for the most part adhere to this tradition, but now use a different cutting tool for every single girl in order to avoid the risk of infection through multiple use. Only 14 percent of the trimmers should use blades multiple times. Infibulation is also partly replaced by lighter forms of circumcision. The proportion of interventions carried out by medically trained personnel and under hygienic conditions has increased significantly in Egypt, Guinea, Kenya, Nigeria, North Sudan and Yemen. UNICEF attributes this trend towards medicalization largely to the fact that campaigns against female circumcision emphasized the health risks. She takes the view that any circumcision, including medicalization, constitutes a violation of human rights that is incompatible with the dignity of women and that campaigns should take up this aspect more intensively.

The trend observed in various countries towards lowering the age of circumcision may also be due to the endeavors to do so. Traditionally, circumcision was essentially performed during puberty or not until adulthood. In the meantime, girls are increasingly being circumcised as early as infancy, even if a later point in time is traditionally customary - so circumcisions can be kept secret from the authorities. In addition, older girls, especially if they have received schooling and education, are more likely to oppose the intervention.

Existential threats in the areas of proliferation, such as extreme poverty and wars, contribute to the fact that both awareness of the problem of circumcision and campaigns and termination strategies take a back seat. Surveys of women and men showed that under such conditions the topic is neither morally nor scientifically of great interest.

criticism

Since the beginning of the abolitionist efforts during the colonial period , these have been embedded in a discourse of the cultural superiority of Europe and part of the “civilization” of Africa. Original efforts to abolish it were often justified on religious grounds, circumcision was condemned as a pagan ritual and converts had to renounce it, including circumcision. A survey of Protestant pastors among the Sara , an ethnic group in Chad, showed that the mission's fight against circumcision is still carried out today in the sense of the eradication of local customs and religious practices. Accordingly, the efforts to get rid of the population were often viewed by the African side as unjustified interference in their own culture. In addition to existing motives for circumcision, this became an expression of one's own cultural identity, and the advocacy of circumcision became part of anti-colonialism .

After a ban was enacted in Sudan in 1945, two women were brought to justice for the first time the following year. The negotiation was followed by violent anti-colonial protests, whereupon the colonial administration severely restricted the implementation of the ban. Circumcision became an anti-colonial symbol and an expression of northern Sudan's national identity. In 1956 the Ngaitana movement emerged in Kenya after the all-male town council of Meru unanimously passed a ban on genital cutting under pressure from the colonial administration. As a result, girls and women who were previously uncircumcised were circumcised in order to protest against heteronomy and to express their physical autonomy. The Ngaitana became part of the political Mau Mau movement , which led to the Kenyan independence movement. Its leader, later President Jomo Kenyatta , emphasized the cultural importance of circumcision.

Some authors argue that circumcision is seen as a positively assessed part of one's identity. It is also pointed out that circumcision does not have to lead to a restriction of female sexuality. The criticism of efforts to abolish it is directed against the depiction of the health risks and the effects on the sexuality of women, which is perceived as exaggeratedly negative. Female circumcision is not necessarily advocated, but the discourse on the subject is criticized.

Today the counter-movement exists in both the African and Western countries concerned. It is worn by prominent women of African descent who are themselves circumcised; for example the Kenyan Wairimu Njambi, who teaches at Florida Atlantic University , or Fuambai Ahmadu from the University of Chicago , who originally comes from Sierra Leone. The latter founded the organization African Women Are Free to Choose (AWA-FC) in 2008 , which has set itself the task of objectifying what they consider to be highly negatively distorted reporting on the topic.

Legal assessment

International legal framework

A negative attitude towards the circumcision of female genitals can be derived from Article 3 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights - the right to security of the person . Article 30 of the Declaration can be used as a prohibition in the event that it is interpreted as an act of worship in the exercise of religious freedom in accordance with Article 18 of the Declaration.

Since 1990, the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child has obligated the signatory states to “take all appropriate legislative, administrative, social and educational measures to protect the child from any form of physical or mental violence, harm or abuse [...] as long as it is is in the care of the parents or one of the parents, a guardian or other legal representative or another person who is caring for the child. ”as well as“ to take all effective and appropriate measures to reduce traditional customs that are beneficial to the health of the children are harmful. "

According to Art. 13a of the Arab Charter of Human Rights , “cruel and degrading treatment” must be combated as a criminal offense. The charter has been in force since March 15, 2008.

Article 2 letter d of the Cairo Declaration of Human Rights in Islam declares physical integrity a guaranteed right. The state has to protect this right and it may only be broken within the framework of Sharia law , for example to impose corporal punishment. Article 6 of the declaration also guarantees women a right to dignity.

European Union and other European countries

In the states of the European Union , the intrusion as a violation of physical integrity is a criminal offense ; in Belgium , Denmark , Great Britain , Italy , Norway , Austria , Sweden and Spain , there are also special laws against female genital mutilation . Criminal trials are known from France , Italy and Spain. More recently, flight from circumcision has been increasingly recognized in European countries as a reason for asylum or as a reason for recognition of refugee status ( see also: Gender-specific persecution ).

Germany

Criminal law

The 47th Criminal Law Amendment Act of September 24, 2013 included the new Section 226a of the Criminal Code (StGB; mutilation of female genitals ) with the following wording in the Criminal Code:

“(1) Anyone who mutilates the external genitals of a female person is punished with imprisonment for not less than one year.

(2) In less serious cases, imprisonment from six months to five years can be recognized. "

According to this paragraph, the person performing the mutilation is liable to prosecution in any case. Section 223 of the Criminal Code, which has also been implemented, is superseded by Section 226a of the Criminal Code; with Sections 224, 225, 226 of the Criminal Code, unity is possible. Parents of the circumcised daughter may make inciting , aiding and abetting or complicity under Section 226a of the Criminal Code punishable. Also, indirect perpetration is concerned. The maximum penalty in the case of the first paragraph according to Section 38 StGB is 15 years.

Motivated purely cosmetic procedures, such Intimpiercings or cosmetic surgery in the genital area (for example, the labia reduction ) should be excluded from the scope of criminal law.

Since 2015, according to § 5 No. 9b StGB, acts committed abroad can also be punished regardless of the law of the place of the crime if the perpetrator is German at the time of the act or if the act is directed against a person who is domiciled or resident at the time of the act habitual residence in Germany. Until 2015, parents who took their child abroad in order to have the genitals mutilated there with the help of a third party were only liable to prosecution in the Federal Republic of Germany if either the victim or the perpetrator was a citizen of the Federal Republic of Germany and the act was also threatened with punishment at the scene of the crime ( Section 7 StGB ). It was therefore possible that parents living in Germany had their children genital mutilated in a country (e.g. Sudan ) that did not criminalize genital mutilation without any criminal consequences in Germany.