hysteria

Under hysteria (from ancient Greek ὑστέρα Hystera , German , uterus' , presumably based on Indo- ud-tero , "the protruding part of the body"; see. " Uterus ") is or has been in the psychiatric one neurotic disorder understood that among other superficial , unstable affectivity and a high need for recognition and recognition.

In medical jargon, the term hysteria is largely considered out of date, especially since it is etymologically and historically associated with the uterus , i.e. the female sex, and has a derogatory tone attached to it, but above all because both its diagnosis and its therapeutic approaches were inconsistent. The terms “histrionic reaction”, conversion disorder , conversion hysteria as well as somatization disorder (with frequently changing physical symptoms) and “psychoreactive syndrome” have a similar meaning .

As a medical diagnosis, hysteria in the international classification of mental disorders ( ICD-10 ) has been replaced by the terms dissociative disorder (F44) and histrionic personality disorder (F60.4).

Symptoms

Hysteria is a neurosis in which the need for recognition and egocentrism are in the foreground, but which is often associated with the symbol of a bird of paradise because it does not have a uniform appearance. This was one of the reasons why it was deleted in its original form from common diagnostic systems such as the WHO ICD or the APA's DSM . Traditionally, hysteria was characterized as a psychogenic behavior by a diverse physical symptom without an organic basis, e.g. B. walking disorder, storm movement, paralysis , emotional disturbance, failure of the sensory organs such. B. Blindness or deafness. The prominent German psychoanalyst Fritz Riemann coined the concept of the hysterical personality . Accordingly, the hysteric is one of four basic types of personality .

The term “hysteria” appears problematic, among other things, because it has a pejorative meaning that is related to the alleged gender-specific bond, which is why the term “ conversion disorder ” is used today for the above. Symptoms used. For a very long time, hysteria was even understood as a physical and psychological disorder that occurs only in women and is caused by a disease of the uterus . According to this understanding of the disease, women who suffer from hysteria often have certain personality traits (self-centered, in need of approval, addicted to criticism, unreflected, etc.).

Some manifestations of hysteria have been interpreted as a subtle struggle against (male) superiority. However, there are also theories that focus on the power of the mother or that of the mother-child bond . The pathologization and treatment made these behaviors on the one hand a disease; at the same time, however, they restored the attacked superiority on another level. This benefited both sides of the doctor-patient relationship , the patient and the doctor.

History of the clinical picture

Ancient roots

Hysteria is considered to be the oldest of all mental disorders observed. In the ancient descriptions of hysteria in ancient Egyptian papyri of the 2nd millennium BC as in Plato (in Dialogue Timaeus , 91 a-d) and in the Corpus Hippocraticum , the cause of the disease named in the Corpus Hippocraticum pniges hysterikai is seen in the "diseased" uterus . Conceptually, they went among others, that the uterus, if they do not regularly with seeds ( sperm fed) will, in the body seeking roving about , in case of suffocatio can rise up to the heart, and then even festbeiße the brain . In addition to other symptoms of illness, this then leads to the typical "hysterical" behavior or "hysterical attack", since the uterus, according to Hippocratic medicine, exerts pressure on other organs such as the diaphragm and the respiratory organs during its migration in the body and thus also causes an attack of suffocation.

The idea of a wandering uterus was contradicted for the first time by the English doctor Thomas Sydenham , who in 1682 wrote a letter to William Cole that had become famous in an essay on hysteria, which he regarded as hypochondria . Jean-Martin Charcot and Sigmund Freud later pointed out that hysteria does not only occur in women, something that was hardly denied from the 1880s onwards.

19th century

In 1888, Paul Julius Möbius provisionally defined hysteria as all those pathological phenomena caused by ideas. This corresponded to the general understanding of hysteria before 1895 and practically covered a large part of all mental illnesses. The clinical picture was therefore very unspecific and extensive. The main characteristic of the hysteria was that no somatic causes could be identified. It was diagnosed frequently in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

In the 20th century, the spectrum of treatment for hysteria included clitoridectomy to remove "hysterogenic zones".

19./20. Century: Charcot, Freud and Breuer

Significantly, Sigmund Freud's path to psychoanalysis also led through hysteria, whereby Freud referred to the hysteria specialist Jean-Martin Charcot . What Sigmund Freud found at the Salpêtrière in those years was a professionalization in science policy. This led to the extensive scientific policy funding for the internationally successful hysteria research project, which is interesting with its erotic focus and representative of the French research landscape , from whose radiance the young Freud also benefited. The treatment methods at the Salpêtrière, however, were already used by contemporaries from other universities, e. B. by the school of Nancy , strongly criticized ( Bernheim ). To get a picture, it is quoted:

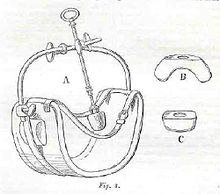

- “They not only published their utterances from the verbal delirium and the corresponding, extremely exciting photographs, but they were also presented publicly in the leçons du mardi . On this occasion you could ... put her in a tetanus and then maltreat her with hypnosis, magnets, electric shocks and the special contemporary highlight, the ovary press . "

The so-called hysteroepileptic clinical picture of the patients was also documented photographically and in writing. In 1982, Georges Didi-Huberman assumed in his reader-oriented interpretation L'Invention de l'hystérie that it was Charcot who prepared these scientific elaborations; the more recent research however names the French doctor Désiré Magloire Bourneville and his photographic collaborator Paul Régnard (Gauchet / Swain) as the originator. Their protocols and photographs showed by no means manipulative patients (Didi-Huberman), who anticipated medical diagnoses and provided theatrical visual material with which they wanted to exercise sexual power over the protocol staff of the Salpêtrière and sexual promiscuity (Didi-Huberman). The current research honors the independent literary and artistic authorship of the two employees and thus does justice to the science-propagandistic dimension of the hysteria project around 1870.

Later, together with Josef Breuer , Freud published his “ Studies on Hysteria ”, published for the first time in 1895, fully edited with the edition of 1922. These studies are generally regarded as the first works of psychoanalysis; the term “psychoanalysis” is also used here for the first time (see history of psychoanalysis ).

Change of concept under Freud

The term "hysteria" was redefined by Freud - in an emphatic departure from Charcot and his martial apparatus of the ovarian press - whereby he introduced the term conversion neurosis, because in his opinion psychological suffering was converted into physical here. However, this renaming has not been able to prevail, especially since it was later recognized that almost every psychological ailment causes physical symptoms that by no means have to show "hysterical" characteristics. Until 1952 this term was used as a collective term for a large number of not clearly defined and exclusively female complaints, until it was removed from the list of diseases by the "American Psychiatric Society".

Theories of etiology

The introduction of etiogenetic criteria with regard to a psychological process typical of a disease also goes back to Freud and Breuer . Freud saw it as the real problem, because it could not be identified with the information freely given by the hysteric. It appeared that the patient was trying to hide this process. At first Freud assumed that repressed events in childhood, especially of a sexual nature (see seduction theory ) were decisive for the development of hysteria. Freud rejected this theory in favor of his later established theory of unconscious ideas, which was also suitable for the development of an etiogenetic explanation and for the development of psychoanalysis as a form of conversation therapy without the use of hypnosis .

Usage today

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| F44.- | Dissociative disorders [conversion disorders] |

| F60.4 | Histrionic Personality Disorder |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

In the 1980s, the concept of hysteria was critically examined, with the result that the term was removed from medical terminology. Attempts to maintain concepts such as conversion neurosis or hysterical neurosis have not been successful.

Stavros Mentzos initiated a move away from describing symptoms to a mode of neurotic conflict processing (initially referred to as hysterical). He saw this initially in a changed self-representation or then in an unconscious staging. He thus also influenced the discussion in the Operationalized Psychodynamic Diagnostics (OPD), which provides an Oedipal conflict for classification. In this, an arc is drawn between people who emphasize their sexuality very much (“active mode”) and others who pay as little attention as possible to it (“passive mode”), i.e. between “ Don Juan ” and “ gray mouse ”.

The term histrionic personality disorder exists in both the ICD-10 and the DSM-5 .

The term hysteria lives on in colloquial usage; but often as before only as an adjective. ( René Kaech points out that it was the French doctors Joseph Lieutaud (1703–1780), François Boissier de Sauvages de Lacroix (1706–1767) and Joseph Raulin (1708–1784) who were the first to use the noun hysteria .) This means a person or behavior that is characterized by theatrics and an exaggerated expression of feelings - sometimes with a sexual touch.

literature

News about the disorder

- Working group OPD: Operationalized Psychodynamic Diagnostics OPD-2. The manual for diagnosis and therapy planning. Huber, Bern 2009, ISBN 978-3-456-84753-5 .

- Christina von Braun : Not me. Logic, lie, libido. 3. Edition. New Critique, Frankfurt am Main 1990, ISBN 3-8015-0224-4 .

- Johanna J. Danis : Hysteria and Coercion. 2nd Edition. Diotima, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-925350-57-8 .

- Peter Falkai, Hans-Ulrich Wittchen (Ed.): Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders DSM-5. Hogrefe, Göttingen 2015, ISBN 978-3-8017-2599-0 .

- Marina Hohl (Ed.): Hysteria Today. Turia + Kant, Vienna 2009, ISBN 978-3-85132-523-2 .

- Lucien Israel : The Outrageous Message of Hysteria. From the Franz. By Peter Müller and Peter Posch. Reinhardt, Munich / Basel 1983, ISBN 3-497-01045-6 (title of the original French edition: L'hystèrique, le sexe et le médecin , by Masson, Paris 1976, 1979, ISBN 2-225-45441-8 ).

- Thomas Maria Mayr : Hysterical body symptoms. A study from a historical and intercultural point of view. VAS-Verlag, Frankfurt 1989, ISBN 3-88864-020-2 .

- Stavros Mentzos : The Change in Self-Representation in Hysteria. A special form of regressive de-symbolization. In: Psyche . Volume 25, 1971, pp. 669-684.

- Stavros Mentzos : hysteria. On the psychodynamics of unconscious stagings. 9th edition. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2009, ISBN 978-3-525-46199-0 .

- Regina Schaps: Hysteria and Femininity. Science myths about women. Campus-Verlag, Frankfurt 1982, ISBN 978-3-593-33119-5 .

News on the history of psychiatry

- Johanna Bleker : Hysteria - Dysmenorrhea - Chlorosis. Diagnoses in lower class women in the early 19th century. Medizinhistorisches Journal 28, 1993, pp. 345-374.

- Jean-Pierre Carrez: Femmes opprimées à la Salpêtrière. Paris 2005.

- Elisabeth Malleier : Forms of Male Hysteria. The war neurosis in the First World War. In: Elisabeth Mixa (Ed.): Body - Gender - History. Historical and Current Debates in Medicine. Studien-Verlag, Innsbruck / Vienna 1996, ISBN 3-7065-1148-7 .

- Karen Nolte: Lived hysteria - explorations of everyday history on hysteria and institutional psychiatry around 1900. Würzburger medical history reports 24, 2005, pp. 29–40.

- Georges Didi-Huberman : The Invention of Hysteria. Jean-Martin Charcot's photographic clinic. Fink, Paderborn 1997, ISBN 3-7705-3148-5 (French first edition 1982).

- Marcel Gauchet , Gladys Swain: Le vrai Charcot: les chemins imprévus de l'inconscient. Paris 1997.

- Helmut Siefert : Hysteria. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , p. 650.

- Jean Thuillier: Monsieur Charcot de la Salpêtrière. Paris 1993.

- Ilza Veit: Hysteria. The history of a disease. Chicago 1965.

- Michael Zaudig : Development of the hysteria concept and diagnostics in ICD and DSM up to DSM-5. In: Regine Scherer-Renner, Thomas Bronisch, Serge KD Sulz (Ed.): Hysterie. Understanding and psychotherapy of hysterical dissociations and conversions and of histrionic personality disorder (= Psychotherapy. Volume 20, Issue 1). CIP-Medien, Munich 2015, ISBN 978-3-86294-028-8 .

Significant works in the history of psychiatry

- Hippolyte Bernheim : Hypnotisme et suggestion: Doctrine de la Salpêtrière et doctrine de Nancy. In: Le Temps, January 29, 1891.

- Désiré-Magloire Bourneville , Paul Régnard: Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière. Paris 1875-1890.

- Josef Breuer , Sigmund Freud : Studies on hysteria. Fourth, unchanged edition. Franz Deuticke, Leipzig / Vienna 1922.

- Paul Briquet : Traité clinique et thérapeutique de l'hystérie. Paris 1859.

- Philippe Pinel : La médecine clinique rendue plus précise et plus exacte par l'application de l'analyse: recueil et résultat d'observations sur les maladies aigües, faites à la Salpêtrière. Paris 1804.

- Paul Richer: Études cliniques sur la grande hystérie ou hystéro-épilepsie. Paris 1885.

- Thomas Sydenham : Opera universa. Leiden 1741.

- Georges Gilles de la Tourette : Traité clinique et thérapeutique de l'hystérie d'après l'enseignement de la Salpêtrière. Foreword by Jean-Martin Charcot . Paris 1891 ff.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Johann Baptist Hofmann : Etymological dictionary of the Greek. Published by R. Oldenbourg, Munich 1950, p. 387.

- ↑ WHO: ICD-10 Chapter V, Clinical Diagnostic Guidelines, Geneva 1992.

- ↑ Reinhard Platzek to: Reinhard Steinberg, Monika Pritzel (ed.): 150 years of the Pfalzklinikum. Psychiatry, psychotherapy and neurology in Klingenmünster. Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 978-3-515-10091-5 . In: Specialized prose research - Crossing borders. Volume 8/9, 2012/2013 (2014), pp. 578-582, here: p. 579.

- ^ Günter H. Seidler (ed.): Hysteria today. Metamorphoses of a bird of paradise. 2nd edition, Giessen 2001.

- ^ Pschyrembel Clinical Dictionary . Founded by Willibald Pschyrembel. Edited by the publisher's dictionary editor. 255th edition. De Gruyter, Berlin 1986, p. 759.

- ↑ Werner Leibbrand , Annemarie Wettley : The madness. History of Western Psychopathology. Karl Alber, Freiburg / Munich 1961 (= Orbis academicus. Volume II / 12), ISBN 3-495-44127-1 , pp. 54–59.

- ↑ Jutta Kollesch , Diethard Nickel : Ancient healing art. Selected texts from the medical writings of the Greeks and Romans. Philipp Reclam jun., Leipzig 1979 (= Reclams Universal Library. Volume 771); 6th edition ibid. 1989, ISBN 3-379-00411-1 , pp. 34 and 141-144.

- ↑ Dissertatio epistolaris ad spectatissimum doctissimumque virum Gulielmum Cole, MD de observationibus nuperis circa cuarationem variolarum confluentium nec non de affectione hysterica.

- ↑ Magdalena Frühinsfeld: Brief outline of psychiatry. In: Anton Müller. First insane doctor at the Juliusspital in Würzburg: life and work. A short outline of the history of psychiatry up to Anton Müller. Medical dissertation Würzburg 1991, p. 9–80 ( Brief outline of the history of psychiatry ) and 81–96 ( History of psychiatry in Würzburg to Anton Müller ), p. 37 f.

- ↑ See also Joachim Radkau: The Age of Nervousness. Germany between Bismarck and Hitler. Hanser, Munich a. a. 1998, ISBN 3-446-19310-3 ; as a paperback ibid 2000, ISBN 3-612-26710-8 , p. 70 f.

- ↑ Reinhard Platzek to: Reinhard Steinberg, Monika Pritzel (ed.): 150 years of the Pfalzklinikum. Psychiatry, psychotherapy and neurology in Klingenmünster. P. 580.

- ↑ Werner Brück: Erotic depictions of hysteroepileptic women . 2008, ISBN 978-3-8370-6917-4 , pp. 87 : "A sa leçon, M. Charcot a provoqué une contracture artificielle des muscles de la langue et du larynx (hyperexitabilité musculaire durant la somniation) [= artificial contraction of the tongue]. On fait cesser la contracture de la langue, maize on ne parvient pas à détruire celles des muscles du larynx, de telle sorte que la malade est aphoné [= loss of the ability to speak; d. V.] et se plaint des crampes au niveau du cou [= cramps in the area of the neck; d. V.]. You 25 to 30 November, on essaie successivement: 1 ° l'application d'un aimant puissant [= strong magnet; d. V.] qui n'a d'autre effet que de la rendre sourde et de contracturer la langue [= she becomes deaf; d. V.]; - 2 ° de l'eléctricité; - 3 ° de l'hypnotisme; - 4 ° de l'éther: l'aphonie et la contracture of the muscles du larynx persistent. Le compresseur de l'ovaire demeure appliqué pendant trente-six heures sans plus de succès. Une attaque provoquée ne modifie en rien la situation. "

- ↑ Alphabetical directory for the ICD-10-WHO Version 2019, Volume 3. German Institute for Medical Documentation and Information (DIMDI), Cologne, 2019, p. 399

- ↑ R. Kaech: The somatic conception of hysteria . In: Ciba magazine . tape 10 , no. 120 , 1950, pp. 1558-1568 .