Circumcision

Circumcision (from Latin circumcisio 'circumcision' ), also male circumcision , is the partial or complete removal of the male foreskin . It is one of the most frequently performed physical interventions in the world and is usually performed for religious and cultural reasons , rarely with a medical indication .

It is estimated that between 25% and 33% of the world's male population is currently circumcised. The circumcision of healthy children on the eighth day of life is considered a command of God in Judaism . The Koran does not specifically mention them. Nevertheless, it is widespread in Islamic countries as Sunna and is carried out in childhood or adolescence. In some societies, circumcision is an initiation ritual ; this ritual symbolizes the adolescent's acceptance into the community of adult men.

Circumcision is one of several treatment options (e.g. triple incision ) that is indicated, for example, in severe forms of pathological phimosis , if treatment alternatives are not promising or previously did not bring healing success.

Circumcision as a routine operation is particularly controversial among minors, even if not nearly to the extent that it would be comparable to the universal outlawing of female genital mutilation . Non-medically justified circumcision is rejected by child protection associations and medical organizations because it irreversibly changes the body and, in the case of boys who are unable to consent, is not in line with health protection and child welfare. In the Anglo-Saxon area there has been a social debate for some time between groups who oppose it (“intactivist” movement) and groups who support circumcision. In particular, the medical benefits and risks are controversial, and in the case of children also ethical and legal aspects, as well as the assessment with regard to human rights , especially the right to physical integrity .

Circumcision in Cultural History and Religion

Origin and ritual meaning of circumcision

The origins of the custom of circumcision are largely unclear. Presumably, tribal patriarchal societies introduced circumcision of both sexes. The oldest traditions of the ritual point to ethnic groups that lived in arid , desert-like regions. Nomads in particular from North and East Africa as well as Australia and their successor religions still practice the religiously motivated circumcision of boys, of girls (see Geographical Distribution of Female Circumcision ) or of both sexes.

Finds of the traditionally used tool point to an origin in the Stone Age . It is assumed here that the procedure initially served to mark tribal affiliation.

Archaeological finds suggest that as early as 7500 BC Chr. The castration as an act of devotion essential part of the ancient Cybele cult was. According to a theory of urologists Mordeniz and Verit, this developed into the custom of foreskin circumcision as a less invasive and bloody procedure. Contact with the cult at the beginning of the 1st millennium BC led to the adoption of the custom in Judaism. Another, more popular argument is that the foreskin is basically the only part of the (male) body whose “sacrifice” does not cause any damage. This reform was a pars-pro-toto sacrifice, which in the biblical tradition - and for the outlined connection between human sacrifice (here the sacrifice of the son Isaac ), circumcision and fertility exemplarily - Abraham undertook the first ( Gen 17.12 EU ).

The ritual or religious circumcision during puberty is considered an initiation rite for both sexes . The growing person is accepted into the community by being consciously brought into a crisis situation in which he should “ show courage ”, “prove himself” and prove to be a “full member”. He often has to endure painful or humiliating procedures. The circumcision of the Bambara and Dogon in the West African Mali represents a rite of manliness, which is supposed to cancel the original androgyny , symbolized by the foreskin as “bewitched femininity”.

In addition to the circumcision of the man's foreskin, there are various forms of surgical interventions on the penis that are still practiced today in primitive peoples as part of such initiation rites . Among the Aborigines (the Australian natives) and on several islands in the West Pacific Ocean , it is a custom to slit open the penis of young men a few weeks after removing the foreskin, which causes a complete or partial split of the urethra , the so-called subincision . In Indonesia , some boys have bamboo or metal balls, so-called implants , placed in the penis shaft or glans at the beginning of puberty .

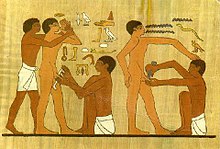

Circumcision in Ancient Egypt

The oldest known representation of circumcision carried out by priests is an Egyptian relief in the mastaba of Ankhmahor, vizier of Pharaoh Teti II , in Saqqara (around 2300 BC). The origins of circumcision in Egypt are associated with the serpent cult there, which is expressed in the worship of the gods Mehen , Wadjet and Apophis . The ancient Egyptians regarded the snake as immortal because it shed its skin and was able to renew itself again and again. Some cultural historians suspect that the circumcision of a man was supposed to symbolically trace the skin of the snake and make the human soul immortal.

Judaism

According to the Torah , circumcision was introduced among the Israelites through a divine commandment to their ancestor Abraham :

“But this is my covenant, which you are to keep between me and you and your generation after you: everything that is male among you is to be circumcised; you shall circumcise your foreskin. That should be the sign of the covenant between you and me. When it is eight days old, you are to circumcise every child of your offspring. [...] But if a male is not circumcised on his foreskin, he will be cut off from his people because he has broken my covenant. "

As mentioned here, circumcision should take place on the eighth day after the birth. It is performed by a Jewish circumciser ( Mohel , plural Mohalim ) who was trained in it. There are different opinions as to whether the Brit Mila should take place without or with anesthesia.

In Judaism, circumcision is viewed as entering into the covenant with God. According to Jewish tradition, God entered into this covenant with Abraham (and his family); therefore the circumcision covenant is also known as the “Abrahamic covenant”.

Just like the Jewish-Hellenistic philosopher Philon of Alexandria in De Circumcisione in the 1st century AD, the Jewish doctor and Rabbi Moses Maimonides also advocated circumcision in the 12th century because of its allegedly moderating effect on the sex drive : the sexual organs were supposed to be injured and are weakened so that they still work, but no longer allow "excess" pleasure . According to Maimonides, the ability to give the wife sexual pleasure is a prerequisite for marriage.

While, according to the (Christian) historical-critical biblical research, most of the history of Abraham was created around 950 BC. . AD are assigned to this form of the Abrahamic covenant until 400 years later with the Priestly in the wake of a comprehensive review of the Pentateuch have been inserted. The same applies to the repeated prescription of the circumcision of boys on the eighth day of life by God in the Torah ( Lev 12: 1-8 LUT ), which is mentioned there in the context of the mother's temporary uncleanness. The original version of the covenant is Genesis 15 ( Gen 15: 1–21 EU ), which Abraham concluded there by means of animal sacrifice.

According to Israeli anthropologist Nissan Rubin, Jewish circumcision did not include the periah for the first two millennia . This was only prescribed by the rabbis in the time of the Bar Kochba uprising (132–135 AD) in order to a. Meshikhat orlah ( repairing the foreskin by stretching) mentioned in the Talmud and the Maccabees ( 1 Makk 1,11-15 EU ) impossible. This had spread under Hellenistic influence, since in Greek society a bared acorn was considered obscene and ridiculous.

Books 1 and 2 Maccabees - which are regarded as Apocrypha according to the Jewish and Protestant understanding - are the oldest known source for the suppression of the Brit Mila . According to the Maccabees, Antiochus IV Epiphanes tried to Hellenize Jews in his empire at the beginning of the second century BC : “[…] He also forbade circumcision and ordered people to get used to all impurities and pagan customs… The women who their sons had circumcised and were killed as Antiochus had commanded; the boys were hung around their necks in their houses and they were also killed who had circumcised them. "( 1 Makk 1,51-64 EU )" Two women were brought before because they had circumcised their sons. The children were tied to their chests and led around the whole city in public and finally thrown over the wall. "( 2 Makk 6,10 EU )

In ( 1 Sam 18,25-27 EU ) King Saul demands a bride price of 100 foreskins of killed Philistines from King David for his daughter, in the hope that he will perish in the process, but the latter then hands over double the amount. In ( Gen 34,14-25 EU ) the brothers Dinas, a daughter of Jacob who was raped by the son of the local Hiwiter prince, demand the circumcision of his tribe as a prerequisite for a compensatory marriage. Here, too, the demand turns out to be a ruse, because two of the brothers use the wound fever of the circumcised to kill everything male in the city without hindrance.

Within the reform Judaism that emerged in Germany in the 19th century , there were voices who wanted to abolish or at least modify the old ritual. In 1844, Rabbi Samuel Holdheim , in his book About Circumcision, took the position that circumcision was not a sacrament and therefore not a necessity for belonging to Judaism. Abraham Geiger , one of the founders of Reform Judaism, which in Germany is referred to as Liberal Judaism , decided to keep circumcision, which continues to apply to Reform Judaism today. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, some assimilated Jewish families did not have their sons circumcised. For example, Theodor Herzl did not have his son Hans circumcised in 1891. Theodor Herzl did not identify with Judaism until 1891; Before he began to found modern political Zionism , he recommended a mass baptism of Jews in St. Stephen's Cathedral in Vienna as a solution to the “Jewish question” .

Currently, most Jewish families - including most non-religious ones - have their sons circumcised shortly after they are born. In the countries of the former Eastern Bloc - it disintegrated in 1990 - according to a mohel working there, only a very small minority of Jewish men is circumcised, which is due to the former communist regime in these countries; According to the mohel, however, the willingness to circumcise is now increasing significantly. In Israel , where, according to Rabbi Moshe Morsenau, head of the Circumcision Unit (Brit Mila) in the office of the Israeli Chief Rabbinate, around 60,000 circumcisions took place in 2011, the proportion of uncircumcised Jewish sons is estimated at 2% and the number of Families who have renounced a Brit Mila, a few thousand. Israeli opponents of circumcision say new polls show that 3% of Jewish Israelis either did not or do not want to circumcise their sons.

Christianity

In early Christianity , Paul of Tarsus spoke out against a duty of circumcision for the newly converted Gentile Christians . Paul himself was a circumcised Jewish Christian . Decisive for him was not the physical circumcision, but - also underlined already in Judaism - "circumcision of the heart" as they already know the fifth book of Moses: "You shall circumcise the foreskin of your heart, and be no more stiff-necked." ( Dtn 10.16 EU ). Anyone who believes, according to Paul, to be pleasing to God and to become holy through physical circumcision alone, is on the wrong track: “Circumcision is useful if you keep the law; but if you do not keep the law, you have already become uncircumcised from being circumcised ” ( Rom. 2.25 EU ). The decisive factor is humble faith : "For in Christ Jesus it is not a matter of being circumcised or uncircumcised, but of having faith that is effective in love." ( Gal 5,6 EU )

He condemned the relapse into a mere law attitude in Philippians in a clear exaggeration: (Phil 3,2-4a: 2) "Beware of the dogs, beware of the evil workers, beware of the intersection." (3) " Because circumcision, that is us, who serve in the spirit of God and boast in Christ Jesus and do not trust in flesh ” - (4) “ although I could also trust in flesh. ”

If one had adhered to the obligation to circumcise male converts, this would have meant a very considerable obstacle for the missionary work of non-Jews and the ascent to a world religion .

With the end of ancient Jewish Christianity as a separate trend, circumcision almost completely disappeared in Christianity. Some Christian churches such as the Coptic Orthodox Church , Ethiopian Orthodox Church and the Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church continue to practice circumcision. In Christianity, the ritual of the circumcision of newborn males, which is also a ritual of the name or its assignment, has largely been replaced by that of baptism .

The Visigoth King Wamba put in a 673 circumcision as punishment for members of his own troops, the Spanish during a campaign women had raped. Those affected were marked as Jews in accordance with the anti-Jewish legislation of the Toledan Empire and expelled from the Christian community.

In 1962 the Second Vatican Council abolished the feast of the circumcision of the Lord (in circumcisione domini) , with which the circumcision of Jesus ( Lk 2.21 EU ) was commemorated eight days after Christmas Eve .

Islam

Circumcision ( Arabic ختان chitān , DMG ḫitān andختن, DMG hatn , Persian andختنه chotne , DMG ḫotne ) is nowregardedby most Muslims as an integral part of Islam . Tradition has it that theProphet Mohammed was born with no or a very short foreskin. Circumcision is now performed among Muslims as a sign of religious affiliation in childhood - up to the age of 13. A large family festival is often celebrated on this occasion. In most cases, the circumcision is done so that the entire foreskin is removed so that the glans is always exposed. The “low & tight” circumcision style is widely used here.

In some countries (e.g. Turkey) boys are circumcised in later childhood. At the family celebration , the Sünnet , organized on this occasion, Islamic elements can mix with traditional elements.

Circumcision is not explicitly mentioned in the Koran and can only be derived from the instruction to follow the religion of Abraham:

“Say, 'What God says is the truth.' Follow the way of Abraham the Hanif ! He believed deeply in God, to whom he did not associate any other deities. "

However, circumcision is mentioned in the hadiths . The following tradition is of fundamental importance:

“ Abū Huraira , may Allah be pleased with him, reported: The Prophet, may Allah bless him, said: Fitra (natural disposition) includes five things: circumcision (of men / boys), shaving off pubic hair, cutting (Finger and toe) nails, plucking (or shaving) the armpit hair and trimming the mustache. "

There is also a hadith according to which Mohammed circumcised his two grandsons al-Hasan ibn ʿAlī and al-Husain ibn ʿAlī , but it is not considered trustworthy because it is not mentioned in either the six books or the Musnad of Ahmad ibn Hanbal .

Nonetheless, the circumcision of the male genitals is a duty for most Muslims and is usually commissioned by the parents for male Muslim children at an early age - often as babies. In the case of Muslims who later convert, circumcision can be carried out through an operation with local anesthesia. It is considered one of the signs of prophethood that the prophets are already circumcised - that is, born without a foreskin. To be circumcised can be interpreted as "following the example of the prophets".

The circumcision costume (Sünnet Kıyafetleri) worn on this occasion is a traditional, religious costume that is mainly used in Turkey , is elaborately made and usually consists of trousers, a shirt, an embroidered vest, a tie or a bow tie, a long one Cape and a striking headgear. The basic color is often white, but it can also be a different color. Shoes and a scepter or dagger are worn for this. Sometimes a sash with the inscription "Masallah" is worn around the shoulder, which in Arabic means "May God protect you".

Yezidism

Also in Jesidentum , which although a monotheistic religion is not on the revelations of Scripture based, circumcision is of boys aged 14 years part of the traditional rites of passage , the Sinet or Sunet is called.

Modern times

In 1712 the pamphlet Onania, probably written by the enterprising quack and writer John Marten and published anonymously, appeared in England : or, the Heinous Sin of Self-Pollution ("Onanism or the hideous sin of self-pollution "), which gradually spread to everyone has been translated and widely used in European languages. It claimed that excessive masturbation could cause a variety of diseases such as smallpox and tuberculosis . Even the great enlighteners of the time believed the anonymously published work. Denis Diderot even included the questionable theses in his encyclopédie . In the 18th and 19th centuries a “campaign against masturbation” took place all over Europe. Countless scientific and popular science publications have appeared denouncing the alleged dangers of masturbation and offering methods of preventing it. The font L'Onanisme. Dissertation sur les maladies produits par la masturbation ("Onanism. Treatise on illnesses through masturbation") by the Lausanne doctor Simon-Auguste Tissot apply. Many doctors of the time believed that masturbation was the cause of “youthful rebellion” and of diseases such as epilepsy , “softening of the body and mind”, hysteria and neuroses .

In Victorian England , circumcision was particularly popular among the upper classes. Via the British colonization (→ British Empire ), circumcision also spread to India (a British colony until 1947), North America, Australia , New Zealand and South Africa. From around 1860 publications appeared that propagated circumcision as “prevention against masturbation” - at that time pejoratively referred to as “self-abuse” - or as a “punishment” for it. Examples:

“ In cases of masturbation, I believe we need to break the habit by bringing the affected parts of the body into such a state that it is too difficult to continue the practice. To this end, if the foreskin is long, we can circumcise the patient with present and likely future benefit. Also, the operation should not be performed under chloroform, so that the pain suffered can be related to the habit we wish to eradicate. "

" A remedy for masturbation, which is almost always successful in young boys, is circumcision [...] The operation should be performed by a surgeon without anesthesia, as the pain associated with it has a beneficial effect on the mind, especially when interacting with the Notion of punishment. "

“ Clarence B. surrendered to the secret vice that is common among boys. I performed a circumcision on him [...] He deserved the just punishment by the pain of the operation after his illicit sensations. "

The number of circumcisions increased. The anti-masturbation motivation can still be found in Campbell's Urology, an English-language standard textbook on urology, in the 1970 edition:

“ Parents readily recognize the importance of local cleanliness and genital hygiene in their children, and are usually willing to take measures that can prevent masturbation. For these reasons, circumcision is usually advised. "

Medically unnecessary circumcision of the penis was removed from the list of paid health insurance benefits in Great Britain after 1949 (the National Health Service was established in 1948 ), and in Canada in the 1990s. In Australia , levels dropped from 90% to 10-20% in the 1970s. In the United States, values fell from around the 1980s (not as sharply and partly indexed by immigration). For more information, see the section " Situation in individual countries ".

present

In the United States, 56% of newborn males nationwide were circumcised before discharge from hospital in 2005 , according to a report by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). In the Midwest , the proportion was significantly higher at 75% than in the West at 31%. The sources differ about the development. While the AHRQ report shows a largely stable rate over the past ten years, other surveys indicate a decrease or an increase.

The number of cases is increasing in Germany. The Scientific Institute of the AOK determined for the outpatient and clinical cases of foreskin operations in boys up to five years of age in 2006 still 5472 operations, in 2011 it was 7,103 cases, although the number of insured boys fell by 5% in the same period. The National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians also recorded an increase of 34% between 2008 and 2011 in the outpatient area alone.

Circumcision is also widespread in English-speaking countries in Africa as well as in the Arab world. There the proportion is over 80% of the population. In Europe the quota is generally rather low, in some countries of Western Europe it has increased or is increasing (as of 2006).

With the exception of the Islamic states, South Korea has the second highest proportion of circumcisions in Asia after the Philippines . For young men this is almost 80%. The circumcision of newborns is uncommon; South Korea is the country with the highest rates of teenage and adult circumcision. The circumcision rate rose sharply in the 1980s and 1990s (in 1945 it was around 0.1%). Circumcision is generally not carried out in South Korea for religious or cultural reasons and is to be seen more as an ideal of beauty shaped by Anglo-Saxon or US-American influences. Since the 2010s, the percentage of circumcisions in South Korea has declined moderately.

In the Philippines , circumcision is largely an obligatory component of the local cultures and is known there as Tulì . It is carried out less for religious and much more for cultural reasons, the origins of which are not fully understood. However, it is largely believed that the rite stems from Islamic influences in the 14th and 16th centuries. Circumcision is usually performed on boys between the ages of 10 and 14 by a local circumciser without any anesthesia with a sharpened knife blade. Due to increasing medical and ethical concerns, the number of medically accurate circumcisions shortly after birth is increasing; other parts of the population, however, still swear by the traditional implementation. Approximately 92% of the male population in the Philippines are circumcised, but contrary to popular belief outside of the Philippines, circumcision is not legally mandatory. However, uncircumcised boys or men are often subjected to humiliation and are socially labeled and vilified as "Supót". Especially in school and puberty age, uncircumcised boys are often seen as a target for bullying by their peers regardless of gender and often have to reckon with severe torture.

Circumcision is used as part of a package of measures under the United Nations Program for HIV Prevention. It is intended to reduce the risk of infection for men during heterosexual intercourse. To this end, campaigns have been started in countries with a high HIV prevalence calling on men to be circumcised. These actions, sponsored by the World Health Organization (WHO) and national governments, have led to a sharp rise in circumcision rates locally. For example, circumcision has established itself among the Luo , a people in Kenya who are traditionally uncircumcised - the Kenyan Prime Minister Raila Odinga had himself circumcised with publicity.

Performing the circumcision

There are several surgical methods for performing a circumcision. In the most common method, the surgeon cuts the foreskin circularly with a scalpel . The surgical technique typically used for medical indications goes back to the founder of plastic surgery, Johann Friedrich Dieffenbach .

In the USA in particular, various methods with different clamps and so-called circumcision kits are in use, which are intended to replace freehand circumcision and, above all, make the suture superfluous (the clamp remains in place until the wound has healed under it).

Various techniques for reducing stress levels have been developed for neonatal circumcision. In 1978, Kirya and Werthman presented the Dorsal Penile Nerve Block (DPNB). For this purpose, a locally effective anesthetic is injected subcutaneously on both sides of the penis base. Lidocaine and bupivacaine can be used as local anesthetics for the DPNB . In a comparative study from 2005, bupivacaine was found to be superior. In 1990 Masciello examined local anesthesia by injecting lidocaine into the penile shaft and found this method to be superior to DPNB in comparison. Stang u. a. recommended in 1997 to reduce stress and pain in addition to the DPNB, the use of a pacifier that was previously dipped in a sucrose solution, as well as the use of a specially designed operating chair. In a traditional Brit Mila, the Sandek has the task of holding the child and calming it down with sweet wine. The systematic review with meta-analysis of the data of several randomized, controlled studies showed in 2001 that the DPNB was the most widely studied method of pain relief in neonatal circumcision, and most effective against the pain of the procedure. Compared to a placebo , the superficial lidocaine application ( EMLA ) was also effective, but less so than a DPNB. Both interventions appeared to the review authors to be safe for use in neonates. None of the investigated methods could completely eliminate the pain-related reactions.

In Germany, non-ritual circumcisions are always carried out with local anesthesia , even for babies . According to the guidelines of the German Society for Pediatric Surgery , anesthesia is required for the surgical treatment of phimosis , supplemented by conduction anesthesia .

General

In Europe, it is common to first grasp the protruding foreskin, which is protruding over the glans, with a clamp and then to cut off this layer that protects the glans. Often the skin ring (inner foreskin sheet) remaining between this incision and the glans rim is also shortened. Depending on the wishes of the patient or his parents or depending on the recommendation of the doctor, a different result can be determined with regard to the amount of skin remaining (see section “ Circumcision styles ”). Another method consists of free-hand circular cutting of the skin at two previously marked areas. This marking is also used to determine how much skin is to be removed and how far away from the glans the healed scar should be. Then the skin lying between the two ring-shaped cuts is removed; the flanking edges are brought together. This type is indicated for a short prepuce that cannot be pulled so far in front of the glans that it protrudes in front of it.

The procedure takes about 15 minutes, after which the wound edges are sewn together with self-dissolving material. The wound usually heals within two weeks. After this time, the threads dissolve on their own. However, sexual intercourse should be avoided for a period of three weeks after the procedure.

Gomco clamp

Gomco Clamp , in German Gomco clamp, is a brand name of the Go ldstein M edical Co mpany and is mainly used in the USA for infant circumcision. The clamp is pushed between the glans and the foreskin and then closed. The foreskin is carefully clamped off. Advantages are relatively low blood loss and relatively quick implementation.

Plastibell

Here a two-part plastic ring is created. One part lies between the glans and the foreskin, the other part outside, at the base of the foreskin. The skin lying between the two applied parts is tied off with a thread. The foreskin falls off by itself after a few days when it is tied. The procedure can be regarded as minimally invasive and relatively painless, but does not take place entirely under medical supervision, so that the doctor cannot intervene in the event of any swelling. If the ring is removed too early, the wound, which has not yet healed sufficiently, can burst open at its edges, which usually requires further intervention in the form of a suture; if this is not done, inflammation often occurs with subsequent bulging scarring.

Extension of the circumcision to the foreskin ligament

Often the foreskin ligament (frenulum praeputii, see " Foreskin "), an individually very different, more or less tight skin bridge on the underside of the penis, stretched between the urethral opening and shaft skin, is also the subject of circumcision. Irrespective of the prescribed amount of removal of the inner and outer foreskin sheet, the ribbon is either only cut through and then mostly sutured again across the wound edges or it is completely cut out. In particular, a short frenulum ( frenulum breve ) can pull the glans down on the erect limb, making the erection crooked and painful. This effect is decisively reinforced by circumcision, especially a radical one. Therefore, especially with "tight" circumcisions, it is usually advisable to at least cut the frenulum ( frenulotomy ), as a rule it should - or must - be cut out completely ( frenulectomy )

Traditional circumcision

In the ritual Jewish circumcision, the Brit Mila , the procedure is performed by a specially trained person, the so-called mohel . The ritual Muslim circumcision (Sünnet) is carried out by the Sünnetci . The usual age for the rite is eight days for Jews and up to about twelve years for Muslims. The blood loss is usually so low that the wound edges are not sewn.

The Jewish circumcision consists of three separate processes: First, the foreskin in front of the glans is gripped with a sickle-shaped clamp and severed with a knife; then the remaining inner foreskin sheet is torn away; and finally the mohel sucks the blood out of the wound by means of a glass tube or with his mouth and wets it with a little wine to clean it. Some Mohalim are doctors these days. According to the orthodox understanding, a process symbolizing the religious act of Brit Mila must be carried out on men and boys who have already been circumcised and convert to Judaism , because a secular circumcision that has already been carried out does not do justice to this claim; In this symbolic act, at least a drop of blood (Tippat Dam) is to be produced through a small opening in the skin as a literal translation and at the same time the name of the ceremony. According to the liberal understanding, this action can be dispensed with when converting .

Clipping styles and shapes

In men, circumcision removes part or all of the foreskin . The circumcision variants therefore vary in terms of tightness and placement of the scar: In everyday language, the different circumcision styles are described using English terms. A distinction is made between low , with the scar close to the glans , and high, with the scar on the shaft, further away from the glans. With a low circumcision , the inner foreskin is almost completely removed. According to the tightness of the shaft skin, a distinction is made between loose , whereby the glans can still be partially covered when not erect, and tight , whereby the glans is always exposed and the shaft skin has very little or no freedom of movement during an erection . This results in the circumcision styles high & tight , high & loose , low & tight and low & loose . If both the inner and outer foreskin sheets are removed so far that the glans is always exposed, even in the non-erect state, and only a few - up to ten - millimeters of inner foreskin remains, this is generally referred to as "radical circumcision"; this also as an indication, provided that the complete removal of the foreskin is medically indicated. While the fact that the limb has been trimmed in the high styles is usually clearly recognizable by the different color tones of the skin above and below the circumcision seam, this is only indicated in a narrow strip in the low versions due to the lack of a lighter inner layer of the foreskin the glans furrow or not at all; when the scar is directly behind the glans, the penis looks as if it has always been without a foreskin. In addition, the color of the circumcision scar itself often differs from the surrounding skin, which is also more evident in the high styles.

While high & tight cuts are mainly used in the USA , the low styles are more common in Europe.

If only part of the foreskin is removed so that the glans is still partially covered when the limb is at rest, “scar phimosis” can occur. In particular, if the circumcision was "high & loose", the circumcision scar sometimes even lies at the level of the glans tip when at rest, but often at least in front of the wider glans rim. If the scar tissue then grows together in bulges or contracts during healing, a circular ring is created in the scar area, which acts like a phimosis, constricting the glans. These cases inevitably require a second circumcision, which will or must be more radical, so that any new scar constriction caused by the condition can no longer affect the glans.

There are other types of foreskin circumcision besides those mentioned. As a rule, these are only to be found regionally and play a subordinate role. An example of this would be the back incision or plastic enlargement, in which the foreskin is not separated, but only partially incised.

→ Prepuceoplasty for phimosis

Indications

A medical indication for circumcision is according to an updated European guideline for chronic inflammatory diseases such as Crohn Zoon (= balanitis Plasmacellularis), lichen sclerosus et Atrophicus (chronic inflammatory disease of the foreskin) in therapy- Lichen Planus in recurrent bowenoid Papulose in Carcinomas and a non-repositionable paraphimosis . Also for scarred phimoses , for example after extensive balanopostitis .

A study carried out between 1996 and 1999 at the Dermatological Clinic and Polyclinic of the LMU Munich showed a clear superiority of circumcision (possibly with additional conservative follow-up treatment) of chronic inflammatory diseases and precancerous diseases such as lichen sclerosus et atrophicans, secondary phimosis, balanitis / balanoposthitis, Condyloma acuminata, Queirat erythroplasia, Bowen's disease, and paraphimosis versus conservative treatment alone.

Colonization with condylomata acuminata (genital warts), on the other hand, is primarily treated with a laser or “icing” with deep-frozen liquid nitrogen .

An indication can be seen in individual cases in a foreskin constriction that is not caused by scarring or lichen sclerosus, the so-called phimosis , which, however, occurs relatively rarely in adults. A narrowed foreskin is normal in infants and children ("physiological phimosis"). Phimoses that have not been healed can also be treated conservatively (ointment treatment with a corticoid) or with enlargement plastic.

Contraindications

Circumcision in childhood should not be performed if there is hypospadias or penile hypoplasia , as the foreskin may be required for later reconstructive surgical measures.

Hygienic and health-preventive motives

Beyond medical indications, circumcision advocates put forward some health-preventive motives. The following physiological relationships are relevant for disease prevention :

- The germ colonization of the acorn is made more difficult. Physiologically , the preputial space (the space between the foreskin and glans) of an uncircumcised penis behaves like an intertriginous space. Also pathogenic bacteria such as coagulase positive staphylococci , Escherichia coli , Proteus mirabilis or Pseudomonas aeruginosa are not rare. There are also yeasts , especially Malassezia species (however, these are part of the normal human skin flora ). The circumcision creates “dry conditions” on the glans, which is considered to be a “more favorable basic situation” with regard to the risk of infection in this area. When the glans is exposed, the germ colonization is quantitatively significantly lower.

- The development of smegma is prevented. The male smegma preputii consists of the sebum of the foreskin glands mixed with the cell detritus of the glans epithelium and bacteria . It collects on the uncircumcised penis between the foreskin and glans. If the genital hygiene is inadequate , the deposits become visible and an intense odor develops. The accumulation of smegma is considered to be the source of inflammation (→ balanitis, balanoposthitis ) and can also promote the development of local carcinomas (→ penile carcinoma ). Most experts currently assume that the smegma does not have a direct causal effect ( i.e. it contains carcinogens ), but can increase the risk of penile cancer by promoting irritation and inflammation.

- The transmission of viruses is made more difficult. The Langerhans cells and CD4 receptor cells, which are present in high concentrations in the foreskin itself and close to the skin surface, are jointly responsible for the transmission of viruses during sexual intercourse.

Whether and in which cases the foreskin removal should be recommended as a routine operation remains controversial. The possible hygienic and health benefits ascribed to circumcision, on the one hand, should be weighed against the possible risk of complications of the operation and alternative prevention options on the other, taking into account the respective basic frequencies of the diseases under consideration. Removal of the foreskin is in no way a substitute for adequate genital hygiene and safe sex measures.

The routine circumcision of children and newborns is viewed by many professional organizations as a purely cosmetic or cultural matter; arguments relating to health and prevention are rejected. Bremen health insurance doctors refuse to settle such circumcisions at the expense of health insurance companies.

Urinary tract infections

The risk of a urinary tract infection is reduced after circumcision. In a meta-analysis of 12 studies, for example, the likelihood of urinary tract infections in circumcised people is roughly 8 times lower; the general risk of girls compared to boys is higher by this factor. However, the risk of a urinary tract infection in otherwise healthy boys was only about 1%: In the first year of life, 1 to 2 of 1000 circumcised boys develop such infections, of uncircumcised boys 7 to 14; Premature babies and children with urinary catheters are particularly affected by the latter . In boys with frequent urinary tract infections or vesicorenal reflux , the preventive effect of circumcision was more relevant. The authors of the meta-analysis therefore see a net benefit of circumcision only in boys with frequent urinary tract infections.

Penis inflammation

A balanitis (including balanitis called) is a purulent inflammation of the glans, which usually starts in the ring groove. The foreskin can also be affected, in which case it is called balanoposthitis . It is characterized by burning and itching and a rash. Fergusson et al. a. In 1988, when 500 New Zealand boys aged 8 years were examined, found 7.6 cases of penile inflammation among the circumcised and 14.4 cases of inflammation among the uncircumcised per 100 boys. In a study from 1990, balanitis was observed much less frequently in men who were being treated for skin diseases (“dermatology patients”) if the patients were circumcised. The inflammation rate in diabetic uncircumcised was again considerably increased. In contrast, Van Howe observed in 2007 when boys under 3 years of age were examined in rural northern Wisconsin that penile inflammation was approximately eight times more common in the circumcised in this age group than in the uncircumcised.

Risk of infection from HIV

Studies suggest that the risk of HIV infection during unprotected, heterosexual intercourse with HIV-infected partners may be lower for circumcised men than for uncircumcised men. The meta-analysis of the Cochrane Collaboration from 2009 showed a reduction in the relative risk of infection for heterosexual men by up to 66% after medically performed circumcision . For this purpose, data from three large, randomized and controlled studies that were carried out in Kenya , Uganda and South Africa between 2002 and 2006 were evaluated. As the authors emphasized, the studies evaluated did not assess the effects of circumcision on the female partners of HIV-infected men. After evaluating the results of the three randomized, controlled studies from Kenya, Uganda and South Africa as well as numerous observational studies, a panel of experts convened by the WHO recommended in a press release in March 2007 that its member states include circumcision as an additional means in their national anti-AIDS strategy.

The World Health Organization, UNAIDS and various non-governmental organizations in 14 selected African countries with many HIV-infected people and a low circumcision rate - including Kenya , Uganda , Zambia , Zimbabwe , Malawi and South Africa - want to achieve that by 2016 around 80% of men and boys there between 15 and 49 years of age are circumcised and there are sustained offers to circumcise all newborn male babies (up to two months old) and at least 80% of male adolescents.

Circumcision for HIV prevention has been criticized from several sides, because on the one hand the risk of HIV infection only decreases (but remains greater than zero) through circumcision and on the other hand the perceived (= subjective) security of circumcised men to reckless behavior Abstaining from condoms , loyalty or abstinence ). In addition, circumcision itself poses a significant health risk, especially in third world countries, as in many places sterile conditions are lacking and circumcision itself can become a source of an infectious disease (or several - for example HIV). The consensus is that the risk of infection by no means falls to zero, so that circumcision cannot act as a substitute for safer sex behaviors.

A South African study from 2008 also came to the conclusion that circumcision had no influence on the transmission of HIV; she thus questions the WHO recommendation. According to the 2011/2012 Zimbabwe Health Demographic Survey, there was a higher HIV infection rate among circumcised people, which Blessing Mutede from the National Aids Council attributes to a false sense of security and the resulting risky behavior. A 2009 USAID report found no clear link between male circumcision and the spread of HIV. For this purpose, data from 15 African countries, Cambodia , Haiti and India were evaluated. While those who were circumcised were relatively less likely to be infected with HIV in eight countries, the remaining ten countries had a higher prevalence of HIV among those who were circumcised.

The pediatrician Robert S. Van Howe and the family physician Michelle R. Storms criticized the "Zirkumzisionslösung" as "wasteful madness", more effective, less expensive and less invasive alternatives withdrawing resources. They believe that circumcision programs are likely to increase the number of HIV infections. Brian J. Morris et al. again, Van Howes rejected this prognosis as misleading. According to the board and management of Deutsche Aids-Hilfe (2008), intensive clarification is necessary in order to counteract the false assumption that one is protected after a circumcision. In the case of men who have sex with men (MSM), no significant difference has been found in previous studies (as of 2010). A meta-analysis of 15 observational studies on MSM found “insufficient evidence that male circumcision protects against HIV infection or other sexually transmitted diseases”.

Men who have sex with men make up the majority of new HIV infections in the West: 61% in the USA in 2009 (from 48,100 for 307 million inhabitants), in 2012 in Germany 73.5% (from 3,400 at 81.9 million). Residents). Men in the USA contributed 7.5% (3,590) to new infections through heterosexual contact, women again 18.3% (8,800); German statistics do not differentiate between the roughly 630 people here by gender. In contrast, the ratio is reversed, especially in HIV high-risk areas: In 2011, heterosexual contacts in Kenya accounted for 77% of new infections (of 104,137 in 39.5 million inhabitants); The same applies to South Africa's new infections (400,000 in 2009 with 49.3 million inhabitants).

Transmission of other sexually transmitted diseases

Studies have also shown that circumcised men have a lower risk of developing genital herpes , ulcus molle and gonorrhea .

With regard to syphilis , the results are contradicting: while some studies found a reduced risk through circumcision, other studies showed no difference to the uncircumcised.

HPV infections

The cervical cancer , also called cervical cancer is the world's second most common malignant tumor in women. It is believed that a large proportion of cervical cancers is caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV). In addition, this group of viruses is suspected of being able to cause genital warts (e.g. genital warts ), vaginal , penile and anal cancers , basal cell cancer and oral tumors. At the same time, the Langerhans cells and CD4 receptor cells found in the penis foreskin are made responsible for the transmission of viruses during sexual intercourse. However, in addition to the foreskin, the penile shaft (corpus penis), the glans ( glans penis ), the scrotum (scrotum) and urine are also involved in HPV transmission.

For the first time in the 1950s, a study compared the incidence ( prevalence ) of cervical cancer in the wives of Jewish circumcised men with that of the wives of non-Jewish uncircumcised men. The wives of the Jewish circumcised men were statistically significantly less likely to have cervical cancer than those of the non-Jewish uncircumcised men. A follow-up study from September 1962 found, however, that cervical cancer is equally common in non-Jewish women regardless of the circumcision status of their husbands. On the other hand, the comparatively lower cancer rate among Jewish women was confirmed:

“The discovery rate for cancer of the cervix among non-Jewish women whose marital partners were circumcised was no different from the rate among non-Jewish women with non-circumcised husbands. Further, the use of a sheath contraceptive by the marital partner, which has an effect equivalent to circumcision in that the cervix is protected from contact with smegma, was found not to be associated with rate differences for cancer of the cervix. In this population, among religious groups, there was no difference between Catholic and Protestant women; for Jewish women this study confirmed the finding of the low rate of cancer of the cervix in this group. "

“The incidence rate of cervical cancer in non-Jewish women with a circumcised partner was not different from that of non-Jewish women with an uncircumcised partner. The use of condoms, which, similar to circumcision, prevents contact between the smegma and the cervix, was also not associated with lower cancer rates. In this sample of religious women there was no statistically significant difference between Protestants and Catholics, whereas the Jews showed a low rate. "

Van Howe's 2006 meta-analysis of three selected studies found no support for the thesis that circumcision reduced the risk of HPV infection. This analysis was carried out in 2007 by Castellsagué et al. a. criticized as "distorted", "inaccurate" and "misleading". The critics' reanalysis of the same data showed a protective effect of circumcision.

Larke et al. found in their systematic review and meta-analysis from 2011 that circumcised men had a lower frequency of genital HPV infections than uncircumcised men. For this purpose, the results of 19 studies were taken into account. In the data from three studies, the authors also found weak statistical evidence that circumcision is associated with a lower HPV incidence and increased HPV clearance .

Albero et al. found a statistically “robust”, inverse relationship between male circumcision and the prevalence of genital HPV infections in men in the 2012 meta-analysis of 21 studies published between February 1971 and August 2010. Further studies are needed to assess the effect of circumcision on the acquisition and elimination of HPV infections. According to the authors, male circumcision could be considered as a one-time preventive intervention to reduce the burden of HPV-dependent diseases in both men and women. This is especially true in those countries where HPV vaccination programs and cervical checkups are not available.

Penile cancer

The penile cancer in the Western world a rare tumor that occurs in men at an advanced age (usually 50 years). In Central Europe and the United States, the incidence was 0.9 per 100,000 men in the 1990s and 1 per 250,000 men in Australia. Carcinoma is responsible for less than 0.5% of cancer cases in men worldwide.

According to a systematic review and meta-analysis from 2011, phimosis is one of the strongest risk factors for the occurrence of penile cancer. Phimosis is likely to lead to smegma buildup and recurrent inflammation, which in turn increases the risk of penile cancer. According to the meta-analysis, men who were circumcised in childhood or adulthood had a significantly lower risk of invasive penile cancer. The results suggest that circumcision protects against this carcinoma in childhood or adulthood. A circumcision eliminates the risk of phimosis; the authors attribute the protective effect in part to the effect of circumcision with regard to the risk of phimosis.

After improperly performed ritual circumcision in Saudi Arabia , the development of a carcinoma based on the circumcision scar was observed in some cases.

Prostate cancer

A Canadian study published in 2014 that examined the correlation between prostate cancer and circumcision on the basis of surveys came to the conclusion that this was below the statistical limits of significance. The authors found a statistically significant correlation for circumcisions carried out at the age of 36 years or older and for blacks, from which the authors concluded that they had a protective effect.

Aesthetic and cosmetic motifs

Some men decide to circumcision for reasons of personal aesthetics and / or their own body image. In an Australian study of the effects of circumcision, circumcised men were less concerned about making their bodies look unattractive during sex.

Female preference

A systematic review article published in 2019 , which summarizes the results of 29 studies from the USA, Australia and various countries in Europe and Africa, came to the conclusion that women prefer a circumcised over an uncircumcised penis: in the vast majority of studies, women expressed a preference for the circumcised penis. The main reasons for this preference were appearance, hygiene, reduced risk of infection and sensation during vaginal intercourse, manual stimulation and fellatio.

In 1988, 269 young mothers in Iowa, USA, who had just given birth to sons, were asked about their attitudes towards male circumcision. 145 participants gave usable answers. Of these, 78% only had sexual experiences with circumcised sexual partner (s), 5.5% again only with one uncircumcised man (or several). 16.5% of the participants - i.e. one sixth - had experiences with both circumcised and uncircumcised sexual partners.

89% of the mothers who answered had had their newborn sons circumcised. The majority (71 to 83%) of the women preferred circumcised male sexual partners for various sexual activities. The reasons given for preferring circumcised sexual partners were hygienic, visual and / and haptic sensations with regard to the penis. The majority stated that they found a circumcised penis to be more aesthetic and / or erotic than an uncircumcised one. About three quarters said the circumcised penis was more natural. The authors also found a strong correlation between the circumcision status of the newborn son and the woman's ideal of the status of her sexual partner during intercourse. Overall, the authors interpret the study results as support for the hypothesis that American women prefer circumcision for sexual reasons. While many women would not consciously view their sons as sexual beings, they may choose to have circumcision based on their own feelings and belief that the son will be more sexually attractive to future sexual partners. However, due to the small number of mothers with mutual experience, the study was later criticized for its informative value.

In another study from 2008 that looked at adult circumcision in men with benign foreskin disease, 38% of partners (and 44% of those who were circumcised) stated that the appearance of the penis had improved significantly.

Women who are looking for arguments to persuade their male sexual partners to circumcise also ask the organization EURO CIRC, which is in favor of circumcision, according to the organization's own information from 2008. The interest in it was justified with personal-aesthetic and hygienic preferences.

Hirsuties papillaris penis

As hirsuties papillaris penis whitish flesh-colored or reddish wart-like formations are called, which the glans edge up to the frenulum of the human penis occur. This harmless anatomical atavism affects around 10 to 20% of the male population . The papillae form in the course of sexual development, predominantly during puberty. From a medical point of view, they do not require treatment, but those affected can perceive them as an aesthetic problem. In addition, there are fears that it may be a venereal disease and the partner might react negatively.

Hirsuties papillaris penis is more commonly seen in uncircumcised men. The mechanism underlying this finding is unclear. The foreskin lying on the edge of the glans with accompanying smegma formation could be an explanation . In a 2009 study, hirsuties papillaris penis was less common in circumcised men. A decrease in the papillae after performing the circumcision was also observed in later life.

Effects on Sexuality

Due to the removal of the heavily innervated foreskin and the keratinization of the glans, the circumcision leads to a reduced sensitivity of the penis. Furthermore, the friction mechanics are influenced during vaginal intercourse . However, the extent to which these changes contribute to restrictions on sexuality or can have a positive influence on it is the subject of controversial scientific debates.

Influence on the sensitivity of the penis

The foreskin contains numerous Meissner tactile bodies , which are stimulated by stretching. In this way, the foreskin plays a role in man's sexuality. By removing the foreskin, the glans is no longer permanently covered; it can become less sensitive through constant contact with the air and rubbing against clothing. Sensitivity can also be reduced by removing the foreskin and frenulum themselves, as both have numerous nerve endings.

Damage or removal of the frenulum in the course of circumcision can also be viewed critically. In many men this part of the penis is more sensitive than the glans itself. This certainly also applies to the highly sensitive area of the foreskin, where the outer skin merges into the inner mucous membrane , which, like many mucous membrane boundaries, is a highly aerogenic zone .

A study by the American sex researchers Masters and Johnson from 1966 is sometimes incorrectly cited as evidence that a circumcised penis is more sensitive than an uncircumcised one.

masturbation

Masturbation is still possible even after circumcision. However, depending on the type and extent of circumcision, restrictions on masturbation may be experienced. In their prospective survey of 373 sexually active men, Kim and Pang found that 48% of the respondents found masturbation to be less pleasurable after circumcision, 8% as more pleasurable and 44% no change. After the procedure, 63% of the respondents had difficulty masturbating, 37% found it easier afterwards. Willcourt criticized the study design as bad and distorting: Among other things, all details about the recruitment of study participants were missing and only 138 of the 373 men were selected for the survey. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) referred to the study in 2012 to determine that there was "fair evidence" of reduced masturbation pleasure after circumcision in adulthood. The level of evidence “fair” in the AAP evaluation system stands for the methodologically second-lowest quality in 4 quality levels of the work considered. Tian et al. a. ignored the publication by Kim and Pang with reference to the numerous shortcomings previously identified for their meta-analysis published in 2013 on "Effects of Circumcision on Male Sexuality".

Sexual intercourse

Sexual satisfaction and ability to orgasm

Some recent research suggests that the sensitivity of the glans decreases after circumcision. In contrast, Krieger u. a. In 2008, 64% of the adult Kenyans surveyed as part of an HIV prevention project reported increased penis sensitivity after circumcision and 54.5% reported improved ability to orgasm. Circumcision was not associated with sexual dysfunction in this study.

In 1983 Money et al. a. the loss of stretch receptors in the foreskin and frenulum and a consequent decrease in sexual response, which limits the circumcised man's ability to achieve erections and consequently erectile dysfunction as a possible complication of male circumcision.

For men, the foreskin plays an important role in their sex life due to its erogenous nature (so an orgasm is sometimes possible through its sole stimulation ). In one of Morten Frisch u. a. A comprehensive cross-sectional study , published in 2011 in the International Journal of Epidemiology (IJE) and carried out in Denmark , in which 1893 uncircumcised and 203 circumcised men were surveyed, showed that circumcised men were at greater risk of anorgasmia . Since the influence of psychological factors was excluded using robust estimation methods , the authors attribute the effect to the reduced sensitivity of the penis of circumcised people. In a letter to the editor , Brian Morris, Jake Waskett, and Ronald Gray criticized this study in terms of its methodology and the author's conclusion. The low participation (5395 men were invited and only 2096 ultimately interviewed) could lead to self-selection . Some of the statistical methods used also require precise examination. The von Frisch u. a. The assumed reduced sensitivity of the circumcised penis is without evidence and also questionable because the foreskin is not completely removed for medical circumcisions in Denmark. The tenor of the article agrees with Frisch's commitment as an opponent of circumcision, which was declared under “ Conflicts of Interest ”. In the answer, which was also published, Frisch expressly rejected this criticism. The study was carried out using the common epidemiological and statistical methods that had withstood the peer review process of the internationally recognized and high-ranking IJE. In addition, due to the loss of tissue, full circumcision would lead to an even greater loss of sensitivity than partial circumcision. The Morris et al. a. The criticism made can rather be explained by the fact that the results of the study by Frisch et al. a. did not fit on the agenda of circumcision advocates and activists Morris and Waskett. Morris initially tried to prevent the study from being published by breaking the rules of the peer review process and putting pressure on the editors of the IJE, but failed.

In the study by Solinis and Yiannaki (2007), 65% of the 123 circumcised men surveyed answered that they now need longer to ejaculate, but only 10% of them felt this was an actual improvement. A multinational study in 2005 found an average of 6.7 minutes to ejaculation during vaginal intercourse for circumcised men versus 6.0 minutes for uncircumcised men, but this difference was not statistically significant.

In a two-year study of adults in Uganda, the proportion of circumcised people who were satisfied with their sex life was 98.4%, almost the same as before circumcision (98.5%), while it increased in the intact control groups the satisfaction on the other hand from 98.0% to 99.9%. In the control group, only 0.1% reported erectile dysfunction or ejaculation difficulties; the proportion was three times as high in the circumcised. In their survey of 138 men who were sexually active before circumcision, Kim and Pang found that 6% of the respondents had an improvement in their sexual life, and 20% said it had deteriorated. In the study by Solinis and Yiannaki (2007) of 123 circumcised men, 16% reported an improvement and 35% a worsening.

In a study published in 2013, in which more than 1,300 men in Belgium were interviewed anonymously, the participants reported lower orgasm intensity and reduced pleasure from the circumcised penis and that it was more strenuous to reach orgasm at all. The problems affected both the glans and the penile shaft.

Ejaculation control

The assumption that circumcision is effective against premature ejaculation was partially empirically confirmed in a Turkish study in which 42 men were examined. The circumcision took place in adulthood (the men were between 19 and 28 years old), 39 men were circumcised for religious reasons, 3 for cosmetic reasons. The men were examined and questioned before the circumcision and at least 12 weeks after the circumcision. There were no significant differences in function, but on average the time to ejaculation was significantly increased.

In a British study on 84 men who had already been circumcised for medical reasons (mostly phimosis or genital lichen sclerosus ) before the study was carried out , 64% of the participants found no change in premature ejaculation after circumcision, 13% an improvement and 33 % deterioration.

Another study in the field of HIV prevention in high-risk heterosexual populations of 2,684 randomly selected men in Kenya on the subject of sexual function and sexual pleasure found that circumcised men seem more able to control the timing of ejaculation themselves or to delay. At the same time, most of the circumcised men reported that they had a much more sensitive penis or that they were able to reach orgasm much more easily.

Effect on the female sexual partner

In 1999, O'Hara's postal survey of women recruited through magazine ads and an anti-circumcision newsletter on the premise that they had experience with both circumcised and uncircumcised sexual partners found that the majority of respondents preferred vaginal intercourse with an intact penis . In 2008, Cortés-González et al. a survey of 19 women showed a significantly reduced vaginal lubrication after the circumcision of the partner. In contrast, the authors found no statistically significant differences with regard to general sexual satisfaction, pain during vaginal penetration, sexual desire and vaginal orgasm. In 2011, Morten Frisch et al. a higher incidence of orgasm problems and dyspareunia if the man was circumcised.

In contrast, in a 2009 study, the overwhelming majority of Ugandan women surveyed (97.1%) reported that they either experienced no change or an improvement in sexual satisfaction after their male partner was circumcised. The authors concluded that male circumcision did not have a deleterious effect on female sexual satisfaction. A study in 2002 of Luo women in Kenya, whose men were circumcised as an adult for the purpose of HIV prevention, found that the women surveyed found sexual intercourse more fulfilling after circumcision. In 2007, Williamson showed a greater preference for US women to perform fellatio and / or manual stimulation when the man was circumcised.

Indirect effects seem to play a decisive role: hygienic attitudes as well as preconceived opinions through socialization influence the partner's judgment regarding circumcision and can have a greater influence on her perception of pleasure than the mechanical-physiological changes, as surveys in Kenya and Malawi have shown.

Possible problems and complications from circumcision

Circumcisions imply a significant complication rate . Depending on the definition, it is given between 0.06% and 55% or estimated between 2% and 10%. There are also deaths, especially after the circumcision of newborns, in which even a small amount of blood loss is at risk of life.

Medical complications

Pain and post-operative discomfort

The procedure causes pain; these can last for a few days. For pain treatment, there are surface anesthetics such as lidocaine (EMLA) and benzocaine , which are applied to the skin as a cream or ointment, and a conduction anesthesia of the dorsal nerve penis by injection . Numerous clinical studies and systematic reviews by the Cochrane Collaboration have shown that surface anesthesia does bring about pain relief, but that effective and effective pain treatment can only be achieved with conduction anesthesia. The Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices has revoked the indication of the numbing ointment EMLA for newborn circumcision.

Other acute complications that can occur with any surgical procedure are bleeding and infections caused by unsterile wound care. Postoperative wound pain is also possible, as is pain when urinating . After the operation, you may notice irritating rubbing against clothing; after a few days or weeks this sensation diminishes in the majority of those operated on.

Meatal stenosis

Meat stenosis refers to the pathological narrowing of the urethral opening , which occurs predominantly in babies and small children. It is one of the most common complications resulting from infant circumcision. A 2006 study found meat stenosis only in previously circumcised boys. The incidence rates after circumcision are around 10%. A urodynamic examination should be carried out as a follow-up examination, far from circumcision. If left untreated, meat stenosis can lead to secondary diseases of the urinary organs such as hydronephrosis and vesicorenal reflux due to increased flow resistance and urinary retention .

Nodulation of the veins

The dorsal vein (vena dorsalis penis superficialis), which begins at the tip of the foreskin in men, is usually, but not necessarily, severed during circumcision and branches out again over time. This can create knots. Experienced surgeons therefore clamp this vein separately in the course of the circumcision and sew up its stump to prevent such a knot.

Adhesions

Furthermore, there may be an adhesion between the skin of the glans and the surrounding skin of the penis, creating a skin bridge, which, if necessary, requires an outpatient surgical correction.

Such a correction is also urgently advised if the remaining shaft skin is sewn close to or even onto the glans rim in the course of circumcision after removing the inner foreskin, which occasionally happens, especially when circumcising small children by inexperienced surgeons. The resulting skin pockets can lead to inflammation and, above all, to disabilities during sexual intercourse. In addition, the result, even after surgical correction, is damage to the glans, which has an irreversible negative effect both in terms of sensitivity and in the cosmetic result.

Herpes risk

The Jewish Orthodox Metzitzah B'peh ritual (sucking blood from the baby's penis with the mouth) is controversial in the United States because it has resulted in multiple herpes simplex type 1 (HSV-1) infections , brain damage, and death Has.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that around 3,600 newborns per year in the 250,000-strong community of ultra-Orthodox Jews in New York undergo the traditional procedure. The 2005 appeal by New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg to distance oneself from this practice was rejected on the grounds that oral-genital circumcision was safe.

The last known case of herpes from Metzitzah B'peh became known in 2019. Between 2000 and 2015, more than a dozen babies fell ill and 2 died in the United States.

necrosis

Glans necrosis can occur as a result of a cauterization injury in the Gomco technique or because of a distal displacement of an incorrectly sized Plastibell ring. Mild cases of necrosis can be treated with local wound care and topical antibiotics, more severe cases surgically. Individual reports of complete necrosis of the glans and penis, where a sex reassignment was performed after several repair attempts, are rare . In the case of David Reimer , the penis was irreparably injured by electrocautery during a medically indicated circumcision in 1966 . His parents therefore decided, on the advice of sexologist John Money , to have sex-changing surgery and to raise the child as a girl. Gearhart and Rock reported in 1989 on four cases of circumcision by means of electrocautery, in which the penis was first amputated after the initial injury and then a feminizing genitoplasty was performed. The authors rated the early feminizing genitoplasty as an “excellent method for the reconstruction of an external genitalia” in such cases. This practice was criticized early sex reassignment after injury of the male genitals in 1997 by Diamond and Sigmundson.

Accidental amputations

Accidental glans amputations are extremely rare, but are a devastating complication of attempting circumcision with the Mogen clamp. The Mogen clamp obstructs the surgeon's direct view of the glans prior to incising the foreskin. Ben Chaim et al. found one case of accidental partial amputation of the glans penis among 19,478 newborn circumcisions carried out and documented in Israel in 2001. The circumcision was done by a mohel. Gluckman et al. reported in 1995 the successful reattachment of an accidentally amputated glans. The injury occurred during neonatal circumcision with a Sheldon clamp.

Yilmaz et al. reported in 1993 the case of an accidental penile amputation that occurred during the ritual circumcision of a 10-year-old boy. The penis was successfully reattached.

Deaths

Douglas Gairdner reported 16 to 19 deaths in England and Wales from neonatal circumcision in the 1940s. Sydney Gellis noted in 1978 that, in his view, there were more deaths from complications from circumcision than cases of penile cancer.

Publicly recorded deaths directly related to circumcision include:

- in June 2008 in Italy

- on April 16, 2010 in Manchester

- in June 2012 in New York

In Africa there are sometimes drastic numbers of fatalities due to ritual circumcision celebrations:

- up to 23 in May 2012 in northeastern Mpumalanga Province, South Africa

- 30 dead in June 2012 in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa

Other risks and complications

The medical literature contains documentation of various diseases and malformations, mostly in the form of case reports , which can occur with different incidence as a result of circumcision. Most of these are rare problems that are often caused by improper implementation.

Circumcision can lead to urinary retention with acute kidney failure , glomerulonephritis (inflammation of the kidney corpuscles), granuloma or even staphylogenic Lyell's syndrome .

Possible malformations as a result of circumcision are penile hypoplasia (a shrinking penis ) or induratio penis plastica (penile misalignment).

Subsequent psychological problems

According to Goldman (1999), circumcision of a child carries the risk of conscious and / or unconscious psychological trauma . The pain, stress and loss of control associated with circumcision could have a negative impact on his psychological development . Behavioral abnormalities became apparent six months after the operation, and the relationship between mother and child could also be impaired, especially if circumcision takes place in infancy, which from a developmental point of view falls into the highly sensitive phase of the formation of the mother-child bond (see also attachment theory ).

Timm Hammond, human rights activist and founder of the circumcision-critical organization NOHARMM, published in 1999 in the British Journal of Urology the results of a survey of circumcised male US Americans organized by NOHARMM as part of a documentation project between 1993 and 1996. 94% of the 546 participants were circumcised in childhood. Among other things, the survey showed that 50% of the participants had a low self-esteem or a feeling of inferiority compared to “intact” men.

According to Lerman and Liao (2001), there is currently a lack of solid scientific data to prove negative psychological and sexual effects of neonatal circumcision.

Controversies about the circumcision of minors

Criticism of circumcision in earlier times

Even in antiquity there was opposition to circumcision, which at that time was practiced exclusively by the Hebrews . In the course of the Hellenization , the foreskin was seen as an integral and desirable part of the human anatomy, the Hebrew tradition of circumcision contradicted it. While circumcision was initially regarded with astonishment as a cultural peculiarity of a minority, but was tolerated, circumcision was banned in 132 AD under the Emperor Hadrian . This law was modified around 140 in the Pandects under Antoninus Pius to the effect that Hebrews had exceptions that allowed legal circumcision.

In the 19th century there was increased criticism of circumcision. The practice was increasingly viewed as an archaic, backward tradition, which would no longer have a place in the modern age shaped by science and enlightenment. The British anthropologist John Lubbock, 1st Baron Avebury described the circumcision of the Jews as a sign of the "barbarism inherent in this people". The physician and chancellor of the University of Tübingen , Johann Heinrich Ferdinand Autenrieth , saw circumcision as a primitive act, which he believed to be practiced by culturally inferior peoples such as Jews and black Africans . In the debate about the meaning of circumcision, like others, he formulated the thesis of a surrogate (substitute) for a human sacrifice . The Italian doctor Paolo Mantegazza , who in the late 19th century was regarded as a "standard source" on the nature of human sexuality, commented on the "mutilation of the genitals" among "wild peoples", which included the Jews. Circumcision “among educated peoples” is “an infamy and a shame”. He appealed to the Jews:

“Do not mutilate yourselves, do not put a mark on your flesh that distinguishes you from other people, as long as you do that, as long as you cannot be our equal. From the very first days of life you pass yourself off with the iron for another race that neither wants nor can mix with ours. "

The Finnish sociologist Edvard Westermarck also regarded circumcision as "mutilation of the genital organ". Together with Auguste Forel , he took the point of view that "the intention of stimulating sexual appetite" combined with the "hygienic advantage" played a part in converting circumcision into a rite.

Criticism of circumcision in the present

While circumcision in adults (to a limited extent also in adolescents) with informed consent does not pose an ethical problem, the procedure in children is the subject of numerous controversies. The main points of dispute are ethical aspects such as the right to physical integrity (“genital integrity”) under the condition of the child's inability to consent, the weighting of medical advantages over risks and complications and the resulting costs for the health system as well as the potential consequences and effects on the Sexuality of the man as well as his partner. These debates are carried out in the specialist literature of various disciplines, mainly medicine and physiology , medical ethics and legal ethics, and cultural anthropology .

Since, in contrast to Central Europe, a high proportion of men are circumcised in the USA, the most violent controversies between supporters and opponents of circumcision can be found there. There are various organizations that have made it their business to abolish the indications-free circumcision of minors. The National Organization of Circumcision Information Resource Centers (NOCIRC) was founded in 1985 as the first group critical of circumcision . In 2008, a joint international campaign by the circumcision-critical groups NORM-UK (National Organization of Restoring Men) and FORWARD (Foundation for Women's Health, Research and Development) was launched under the title “Genital Autonomy”, which oppose any form of circumcision of boys or Girls judge unless this is medically necessary. The campaign particularly criticizes the WHO recommendation on circumcision in the context of HIV prevention ( see above ).

The German circumcision debate that was initiated in 2012 by a ruling by the Cologne Regional Court goes back to the legal scholar Holm Putzke . He sees the circumcision of children as a significant physical intervention that is being played down too much. The law already prohibits light corporal punishment . Then circumcision as an irreversible encroachment on physical self-determination would have to be forbidden.

In a joint appeal, more than 700 doctors and lawyers, including university professors Matthias Franz , Holm Putzke, Maximilian Stehr and Hans-Georg Dietz, called on the federal government and members of the Bundestag to focus on what they believe is the best interests of the child: “There is a remarkable attitude of denial and a refusal to empathize with the little boys, who suffer considerable suffering from genital circumcision”.

The German Academy for Child and Adolescent Medicine e. V. (DAKJ) spoke out on July 25, 2012 against circumcision of minors for religious and ritual reasons. The German Society for Pediatric Surgery (DGKCH) did the same . The professional association of paediatricians expressed itself on August 23, 2012 after the meeting of the National Ethics Council with “incomprehension and horror” (“a child's right to physical integrity obviously does not count!”).