Bar Kochba uprising

The Bar Kochba uprising was a Jewish uprising against the Roman Empire from 132 to 136 AD under the leadership of Simon bar Kochba . After the first Jewish War in 66–74, it was the second or third Jewish-Roman war , depending on whether you count the diaspora uprising 115–117.

Before the fighting broke out, Hadrian had visited the province of Judea in 130 and founded the colony Aelia Capitolina on the site of the city of Jerusalem, which had been destroyed in 70 and where a Roman military camp has since been located . Planning for the uprising began soon after the emperor left the region. Unnoticed by the Roman military , the rebels set up numerous bases of operations for a kind of guerrilla war . Since the Roman army was initially not prepared for this type of warfare, it suffered heavy losses in the initial phase, which had to be compensated by raising troops.

The core area of the uprising was south of Jerusalem in the West Bank . However, the rebels controlled a larger territory, although it is disputed whether the uprising extended to the entire province of Judea, which would also include Galilee. The terms “redemption” and “liberation” are mentioned as goals of the rebels in documents and on coins. Messianic expectations were probably placed on the military leader Bar Kochba. He did not, however, call himself the Messiah , but used the title Nasi .

Emperor Hadrian ordered the governor of Britain , Sextus Julius Severus , to Judea. He took over the command of the Roman troops in 134 with a strategy adapted to the fighting in the mountains. His warfare was aimed at the systematic destruction of the Jewish settlement area. In the autumn of 135 the Roman army stormed the Betar fortress, which was protected by its location on a hill sloping steeply on three sides . According to the literary sources, Bar Kochba died there. In the core area of the uprising, after the end of the war, most of the population was dead or enslaved . Their land ownership fell to the imperial treasury and was partly sold and partly given to veterans.

Research has failed to reach consensus on a number of issues: the immediate cause of the uprising, the extent of the area controlled by Bar Kochba, particularly whether it included Jerusalem, and the extent of the Roman reaction. The basic text is generally the brief report by Cassius Dio , which is only available in an excerpt by Johannes Xiphilinos . It is corrected in individual points and supplemented by other ancient authors. Opinions differ widely on the question of what historical information can be found in rabbinical literature . Text finds from the Judaean desert ( Wadi Murabbaʿat , Nahal Hever ) have expanded the picture of the administration of Bar Kochba.

Possible occasions

The political situation in the year 132 was unfavorable for an uprising: the provinces were calm, the conflict with the Parthians that was hinting at 123–124 had been settled through conciliatory gestures from Hadrian , and after the unsuccessful uprisings in Egypt , the Cyrenaica and Mesopotamia was with one Participation of the Jewish diaspora on Bar Kochba's side is unlikely. Ancient authors name two different measures of Hadrian as immediate reasons for the uprising: for the Historia Augusta it is a nationwide circumcision ban, for Cassius Dio the foundation of the Colonia Aelia Capitolina including the Temple of Zeus on the site of Jerusalem. The founding of Aelia Capitolina was probably connected with Hadrian's visit in 130 and thus belongs in the prehistory, not of the consequences, of the Bar Kochba uprising.

Hadrian's visit to the Province of Judea

On his second great journey through the eastern provinces of the empire, Hadrian visited Judea in the first half of the year. He came from the province of Arabia , probably traveled to Galilee via Scythopolis , visited the headquarters of the second legion at Caparcotna (Hebrew: Kefar Otnai , Arabic: Lajjun ), moved on to the provincial capital Caesarea and from there to Jerusalem, where the Legio X Fretensis was stationed. From Jerusalem the emperor traveled to Egypt on the coastal road via Gaza. For the provincials, from the elite to the common people, this visit by the emperor was an extraordinary event. It offered the opportunity to get in touch with the ruler in a consensus ritual - but only if one participated in the imperial cult .

Hadrian's journey left traces: a Hadrianeum in Tiberias, probably another in Caesarea and possibly the renaming of Sepphoris to Diocaesarea. Hannah M. Cotton and Werner Eck published an inscription from Caesarea, according to which the beneficiaries of Quintus Tineius Rufus , governor of Judea from 130 to 133, had a statue of Hadrian erected on the occasion of the imperial visit. A porphyry statue from Caesarea, which has been known for a long time and has been preserved in fragments, was tentatively associated with this foundation.

Foundation of Aelia Capitolina

The establishment of a colony was a benevolent gesture as it gave residents the benefit of Roman citizenship . A colony already existed in Judea, the provincial capital Caesarea on the Mediterranean coast. Hadrian wanted another to be built in the core area of Judea on the site of the city of Jerusalem, which was destroyed in 70. The recruits of the Roman army usually came from the area around the legion camp. Two legions were stationed in Judea. Therefore, from the Roman point of view, it was advantageous to be able to use another colony in addition to Caesarea as a reservoir for service in the legions. The name Aelia Capitolina contains the gentile name of the city's founder Publius Aelius Traianus Hadrianus and alludes to the cult of Jupiter Optimus Maximus on the Capitol in Rome. It shows the close connection between the ruler's cult and the cult of Jupiter or Zeus . Anthony R. Birley points out that after the destruction of the temple, the Jews had to pay their previous temple tax as Fiscus Judaicus to Jupiter Capitolinus: "Now Jupiter really replaced Jehovah ."

Since the destruction of Jerusalem in the Jewish War , there has been a Legio X Fretensis military camp on the city grounds. A rather small civil settlement is to be assumed in the vicinity of the Legion (craftsmen, traders, landlords). E. Mary Smallwood points out that both the military camp and the civil settlement with their pagan sanctuaries existed in the area of Jerusalem for around sixty years without an uprising of the Jewish population. But the planned new construction of a city with a Greco-Roman character had to destroy all hopes for a reconstruction of the Jewish Jerusalem.

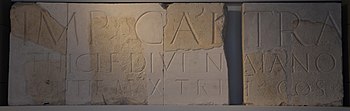

A second fragment, which became known in 2016, completes the inscription of an arch of honor , which the Legio X Fretensis erected on the occasion of the imperial visit (photo):

“Imp (eratori) Cae [sari divi Traiani] | Parthic (i) [f (ilio) divi nerve] ae nep (oti) | Traiano [Hadri] ano August (o) | pont (ifici) ma [x (imo)] trib (unicia) pot (estate) XIIII | [co (n) s (uli) III p (atri) p (atriae) | l [eg (io) XF] reten [sis Antoninia] na (e). ”(To the Emperor Caesar, son of the deified Traianus Parthicus, grandson of the deified Nerva , to the Traianus Hadrianus Augustus, Pontifex Maximus , with the power of attorney for the 14th time of a tribune, consul for the third time, father of the fatherland, of the Legio X Fretensis [nicknamed] Antoniniana.)

The inscription probably belongs to an arched monument that was erected on the northern border of the colony. It suggests that construction on Aelia Capitolina was well advanced by the time Hadrian officially established the colony. Excavations on the edge of the Western Wall Plaza , in the area of the intersection of Decumanus and Cardo secundus (Shlomit Wexler-Bdolah and Alexander Onn, 2005 to 2009) confirm this dating, so that the existence of the Roman city of Aelia Capitolina before the uprising is now well established .

A special coinage (photo) is dedicated to the event. It depicts Emperor Hadrian on the obverse and the foundation act, the plowing of the sulcus primigenius , on the reverse , a sacred furrow that delimited the planned urban area. A military standard ( vexillum ) can be seen in the background , an indication of the colony status.

Aelia Capitolina was to receive a temple of Zeus as the main shrine. Research is divided as to whether this temple should be built on the site of the ruined Jewish temple or instead of this temple, but in the area of the forum of the new city.

Circumcision prohibition

The Historia Augusta dedicates a brief sentence to the Bar Kochba uprising: “At this time, the Jews also started a war because they were forbidden to mutilate the genital organs.” Some historians concluded that Hadrian had issued a ban on circumcision , which we no longer have. This was the reason, or another reason, for the Bar Kochba uprising. Since the source value of the Historia Augusta is questionable, historians who anticipate such a measure will consult a rescript by Antoninus Pius . This rescript is then interpreted in such a way that Antoninus Pius, as the successor of Hadrian, allowed the Jews again to circumcise their own sons, while the circumcision of a non-Jew should be punished like castration. Peter Kuhlmann rejects this understanding of the text from a philological point of view. He interprets the rescript as a restriction of the per se permissible circumcision by prohibiting the admission of non-Jews into the Jewish community. Ra'anan Abusch sees the rescript of Antoninus Pius as the first ever Roman legislation that deals with the Jewish circumcision ritual ( Brit Mila ). Since numerous eunuchs were offered on the Roman slave markets , several emperors had previously seen reason to take action against the castration of slaves. According to Abusch, such a slave protection provision is also in a rescript of Hadrian: He put castration on the same level as murder, thus tightening the punishment. The connection that the Historia Augusta makes between Hadrian's slave legislation, Jewish circumcision and the Bar Kochba uprising is not supported by any classical author, according to Abusch's analysis. Christopher Weikert judges: "It is better to discard the testimony of the Historia Augusta than to build an argument rich in hypotheses on its foundation."

Presence of the Roman military

At the end of Trajan's reign or at the beginning of Hadrian's reign, Judea, previously a praetoric province with one legion, had been elevated to the rank of consular province with two legions. The presence of the Roman military increased noticeably for the local population, and the expansion of the road network points in the same direction, because this infrastructure was primarily used by the army. Mor explains this measure in such a way that after the death of Agrippa II , the area of the province of Judea expanded to include the Galilean toparchies (subdistricts) Tiberias , Tarichea , Abila and Livias-Julia, but the Roman presence in these new areas was initially weak . A social banditry could have developed in this vacuum. Finally, in the year 117 in Galilee there were major unrest (so-called "War of the Quietus"). After its suppression, the Roman military reinforced the identified weak point with an additional legion in Caparcotna on the southern border of Galilee. The Romans reacted directly to rebellions twice in 117 and 132 with troop reinforcements. Therefore, Mor contradicts the thesis that the Romans continuously increased their control over the native population because they assumed that the inhabitants of the province of Judea were constantly anti-Roman and agitated against them.

With the headquarters of the Second Legion in Caparcotna ( location ), the Roman army occupied a favorable position to control the Jezreel plain , in its strategic value comparable to the nearby Megiddo . Road connections existed to Caesarea, Scythopolis , Sepphoris and Ptolemais ( Akkon ). About 12 km south of Scythopolis was another Roman military camp in Tel Shalem (Arabic: Tell er Radgha , location ), where a vexillation of the Legio VI Ferrata is proven by a building inscription. Notable finds have been made in Tel Shalem since the 1970s: parts of a tank statue of Hadrian , another head of a statue and fragments of a monumental Latin inscription. On the basis of the usual form, Eck presented a reconstruction of the text and the arched monument to which it belonged in 1999. However, Eck's date of 136 cannot be based on the surviving parts of the inscription. A victory monument erected by the Roman Senate at this relatively decentralized location means, according to Eck, that Tel Shalem was a battlefield. Another text reconstruction and interpretation suggested by Glen Warren Bowersock . Bowersock fundamentally denies that the location of an arched monument can be an indication of a battlefield not known from other sources. He refers to fragments of a monumental arch that were found in Petra in 1996 . Nor did this monument serve to celebrate an unknown victory. “I suggest that we say goodbye to the idea that close to Scythopolis violent, otherwise unreported battles took place, which is why a Roman triumphal arch was built here. I believe the arch, like all the others, is part of Hadrian's journey in 130. "

People groups in Judea

The population of the province of Judea was ethnically, religiously and culturally non-unit. Caesarea, the provincial capital, had a strong Roman influence compared to other colonies in the east of the empire; Latin was the predominant language. Some former Jerusalem families may have returned to the small civil settlement that had formed in Jerusalem next to the dominant military camp, but veterans had probably also settled there. But a large influx of strangers was necessary for the city to develop. They enjoyed the privileges associated with colony status, such as tax exemption.

According to Shimon Applebaum , the land in Judea became the property of the Emperor Vespasian after the end of the First Jewish War . Veterans, favorites of the imperial family, but also Jewish aristocrats, who were able to divide and sub-lease their leased land, appeared as tenants. The Jewish farmers were practically expropriated and, as small tenants, had to cultivate their formerly own land under unfavorable conditions. The folk traditions preserved in Talmudic literature show that the uprising originated in the oppressed rural Jewish population. The uprising was a social movement that was supported by small farmers. Against this scenario, Applebaum uses rabbinic literature from later times to reconstruct the economic conditions before the war. In addition, the text finds from the time of the uprising show that the system of leasing and subleasing was not shaken.

Older research assumed that the Jewish population was led by rabbis in the 2nd century. An uprising without the support of great Torah scholars like Rabbi Akiba was difficult to imagine. Today the influence of the rabbis is estimated to be less. Seth Schwartz pointedly formulated in 2001 that the “rabbi-centric” view of the Jewish population between the First Jewish War and the Bar Kochba uprising was inappropriate. The rabbis and their circle are possibly a small segment of society, but they feel as an elite. Another part of the population even welcomed the fall of the temple and the Torah in order to be able to join the majority culture. A presumably large group had no contact with their traditional way of life after the traumatization of the First Jewish War. Peter Schäfer believes that Hadrian's plans for Jerusalem were accepted or supported by a group of assimilated Jews. The uprising had escalated from a long smoldering internal Jewish conflict between supporters and opponents of assimilation. There is little evidence of what became of the assimilated population after the fighting broke out. A historically useful note in rabbinical literature shows that at the time of Bar Kochba many Jewish men who had undergone the epispasm were circumcised again. They were probably forced to do this by the insurgents. Some Jews served in the Roman army during the Bar Kochba uprising. Barsimso Callisthenis, for example, who came from Caesarea, was recruited as reinforcement for the Cohors I Vindelicorum at the beginning of the uprising . He was a member of an auxiliary unit and received his military diploma in 157.

Cassius Dio writes that non-Jews also joined the uprising in the early stages. In the Bar Kochba letters, people are mentioned by Nabataean names. It is generally assumed that the underclass in the cities saw the uprising as an opportunity to improve their social status. During the uprising, the Samaritans probably also rebelled against Roman rule in their settlement area, without submitting themselves to the leadership of Bar Kochba.

Preparation and outbreak of fighting

According to all literary sources, the uprising broke out when Quintus Tineius Rufus was governor of the province of Judea. This was already Legatus Augusti pro praetore when Hadrian visited Judea. According to Cassius Dio, the insurrection had been carefully prepared. In Judea there was an arms production facility for the Roman army, with the rebels deliberately producing inadequate weapons so that they could be rejected by the army and then used by themselves. This episode is often considered a fictional element in Cassius Dio's account. On the other hand, Birley says that it was the style of Hadrian's government to demand quality military equipment and therefore reject deliveries that were not up to standard.

Cassius Dio also describes bases of operations that the rebels set up before the fighting broke out and expanded them with shafts, walls and tunnels. Numerous such hiding spots have been identified especially in the Schefela . These underground systems are mostly located within ancient towns. These are artificial caves that are connected to one another by narrow horizontal passages and vertical shafts. The narrow, low entrances could be locked from the inside. There are water reservoirs and niches for lamps in these refuges. Amos Kloner and Boaz Zissu assume that the construction and use of these so-called hiding complexes can be reliably dated to the time of the Bar Kochba uprising, among other things through 25 coins found from all years of the uprising. Other archaeologists suspect that these underground spaces were repeatedly visited by the population in times of need over a long period of time. Their use during the uprising would therefore have to be justified in each individual case by findings. Eck combines both of the preparations for war mentioned by Cassius Dio by considering that the weapons rejected by the Romans were stored in the underground hiding places.

Similar tunnel systems have also been discovered in Galilee. For archaeologists who see such facilities as a preparatory measure for the Bar Kochba uprising, proof is thus provided that parts of the Galilean population were ready to join Bar Kochba (so Yigal Tepper, Yuval Shahar, Yinon Shivti'el) - which then may not have been put into practice.

The uprising broke out in the summer or autumn of 132. The Roman military administration was completely taken by surprise. Auxiliary troops had been stationed throughout the province during the interwar period. The insurgents attacked these small camps. In this way they inflicted heavy losses on the Roman army. Eck suspects: "At least half of the legionaries [of the Legio X Fretensis] were wiped out in one fell swoop." The literary, epigraphic, numismatic and archaeological evidence of the uprising does not provide any information about the actual fighting.

Bar Kochba's government

Own coins

The minting of their own coins is a privilege of sovereign states and was in itself a declaration of war on Rome, as was only carried out among all the rebellious provinces of the empire in Judea - in both wars against Rome. Roman coins with Pagan symbolism in circulation were confiscated and overminted by Bar Kochba's people. According to Ya'aḳov Meshorer, this was both a religious and a political message. In contrast to the issue of new coins, the minting of existing coins was not a source of state income and tied up workers. The rebel leadership accepted this despite the strains of the war, because their own coins offered the opportunity to communicate a message to the population.

Martin Goodman points out the references that the new silver and bronze coins make to those of the First Jewish War: choice of the same motifs (palm trees, lulavim ), the same catchphrases "Freedom - Redemption - Jerusalem", the use of the ancient Hebrew script . The latter is noticeable because at the time of Bar Kochba's the square script had already fully established itself. Despite these references to the past began with the start of the uprising in a new era: In contrast to the coinage of the year 66 to 70 does the term Zion on the inscriptions not before (instead of Israel and Jerusalem) and Schim'on and El'asar be two leaders are named, while the rebel leaders of the First Jewish War do not appear by name on their coins.

Hoard finds from the time of the uprising that do not contain any bar Kochba coins can be understood as an indication of an existing skepticism towards the rebel state. Because the coins of Bar Kochbas were only accepted in this limited area. Exchanging them for other currencies could be risky. Towards the end of the uprising, land lost value and coins were highly valued.

Leaders

Bar Kochba

Nothing is known about the family of the rebel leader Simon Bar Kochba, actually Bar (or Ben) Kosiba. Only the proper name Shim'on appears on the coins , often together with the title Nasi . Both rabbinical and Christian sources as well as the text finds from the Judah desert call his epithet. Kosiba can refer to the place of origin or - more likely - to the name of the father ( patronymic ). A rabbinical note that he was a nephew of Rabbi El'azar haModa'i is judged by Schäfer to be a literary topos without historical relevance. Cassius Dio does not mention Bar Kochba.

In his letters, Bar Kochba shows himself to be an aggressive military leader who personally dealt with disciplinary issues and everyday problems. Obeying the law of religion was important to him. An often-cited example of this is his requirement of palm branches, etrogim , myrtle and willow branches in order to be able to celebrate the Feast of Tabernacles in his military camp . A note from Justin the Martyr is one of the few contemporary pieces of news about Bar Kochba: “During the recent Jewish war, Bar Kochba (Βαρχωχεβας), the leader of the uprising of the Jews, ordered only Christians to pay the most severe punishments if they were not Christ denied and blasphemed. ”According to Schäfer's assessment, a comparison with the Bar Kochba letters shows that the rebel leader acted rigorously against people or groups who did not accept his authority. It is not known why Christians in Judea province opposed Bar Kochba, but it is widely believed that they rejected Bar Kochba as the Messiah.

For a possible messianic claim, Bar Kochba's two motifs are cited on the coins of the rebels as evidence: star and grapes. With the coinage, which shows a temple facade and a kind of star above, Leo Mildenberg specifies that this is a rosette and only one of several ornaments depicted above the temple. Schäfer considers a messianic meaning for the grapes to be conceivable, since in literature they are a symbol of the fertility of the land of Israel in the messianic time. The facade of the temple is depicted on the coins of Bar Kochba as well as motifs from the temple cult, for example musical instruments. It is often concluded from this that the conquest of Jerusalem and the renewal of the sacrificial cult in the restored temple were the main goals of the rebels - although one can disagree as to whether Bar Kochba ever specifically addressed these goals or used the corresponding coinage to motivate his fighters. Schäfer relativizes the fact that motifs of the temple cult were so common on earlier Jewish coins, "that nothing at all can be deduced from them."

What is certain is that Bar Kochba has the title in Hebrew נשיא ישראל" Nasi (prince, prince) of Israel" accepted. A religious charge of the title nasi can be derived from the biblical book Ezekiel (chap. 44-66). The rule of the nasi was expected for the end times (see especially Ez 37,24-25 EU ). In the Qumran literature, too, the title had a messianic ring. In the Mishnah, on the other hand, the title nasi has almost the same meaning as “king” and denotes a secular ruler. As the “ nasi of Israel”, Bar Kochba was apparently the owner of the land in Judea, which he leased. His main role as a nasi was a military one: to liberate Judea from Roman rule. Both the coinage and the documents from the time of the uprising use the key term “salvation” ( Hebrew גאולה ge'ullah ) and "liberation" ( Hebrew חרות cherut ). They represent a complex combination of religious, political and social expectations that his followers directed towards Bar Kochba.

El'azar, the priest

A leading figure next to Bar Kochba, who had coins minted with his name, was "El'azar, the priest". Some Israeli researchers (Baruch Kanael, Yehuda Devir and Yeivin) interpret the title priest as high priest and derive further hypotheses from it about an actual priestly direction of the uprising, which was superior to Bar Kochba. Given the frequency of the name El'azar, identification with any of the people of that name mentioned in rabbinical sources is speculative. In this context, Rabbi El'azar haModa'i, the supposed uncle of Bar Kochbas, is mentioned. William Horbury thinks that the sayings attributed to El'azar haModa'i in rabbinical literature show the color of the time of the Bar Kochba uprising.

Rabbi Akiba

In many depictions of the Bar Kochba uprising, Rabbi Akiba , the great Torah scholar, is assigned the role of organizer. He had traveled around the diaspora to collect funds and supporters for the insurgents. This theory was developed in the middle of the 19th century by Nachman Krohaben and adopted by Heinrich Graetz in his much-received historical work. Akiba proclaimed Bar Kochba the Messiah, was imprisoned by the governor Tineius Rufus and died a martyr. The only sources available for Akiba's biography are scattered references in rabbinical literature. These sources are silent for a political purpose of Akiba's travels. That they were used to promote the uprising is a hypothesis.

Three passages in rabbinical literature relate Akiba and Bar Kochba; they contain the so-called Messiah proclamation: “When Rabbi Akiba saw Ben Koziba, he said: A star (kochab) emerges from Jacob, Kochba emerged from Jacob; he is the messianic king. ”The messianic interpretation of the biblical passage Num 24.17 EU is old. The Greek translation already presupposes it: “A star will rise from Jacob and a person will rise from Israel…” This interpretation was also popular in Qumran , but not limited to this community. The concretization of a specific historical person is new and singular. According to Schäfer's analysis, it cannot be determined whether this identification comes from the historical Akiba or was subsequently attributed to him. It led to the renaming of Bar Kosiba to Bar Kochba ("star son"), or in the later rabbinical literature Bar Koziba ("son of a lie").

Territory controlled by Bar Kochba

The core area of the uprising is a territory bounded by Betar ( Battir ) in the northwest, Hebron in the southwest and the Dead Sea in the east. But the rebel state was bigger. Here it is hoped to come to new knowledge by examining the hiding complexes created by rebels . Based on this criterion, Kloner and Zissu drew the boundaries of the area as follows:

- to the east the Jordan Valley and the Dead Sea ;

- in the west the foothills of the Schefela without the coastal plain;

- in the north a line running from the archaeological site of Antipatris via Alexandreion to the Jordan Valley, ie the assumed north-western corner of the territory is close to the intersection of Israeli highways 5 and 6;

- in the south a line from Beersheba and Arad to the Dead Sea.

Since no coinage of Bar Kochba was found in Galilee or Transjordan, these regions probably did not belong to the area that was under his administration - but this does not rule out fighting there. The question of whether Galilee was included must also be seen against the background that older research assumed that the Jews of Galilee were less “conservative” than those in the Jerusalem area.

The motifs on Bar Kochba's coins, in particular the inscription “For the freedom of Jerusalem”, have repeatedly fueled the assumption that Bar Kochba was able to temporarily bring Jerusalem under his control. This is how Smallwood sees it: The rebels took Jerusalem at an early stage and held it against the Romans for several years. Four papyri from Wadi Murabbaat have also been used as evidence of a control of Jerusalem. They were exhibited after the reading by the excavator Milik in Jerusalem; however, after checking with the radiocarbon method , these documents date from the First Jewish War.

According to Hanan Eshel, the fact that only three Bar Kochba coins were found during archaeological excavations in the city area clearly speaks against control of the rebels over the city. For political and military reasons, too, the capture of Jerusalem by Bar Kochba's fighters must be considered unlikely. To do this, they would have had to defeat the legion stationed there. The Roman side would not have let such a defeat rest, but responded with massive countermeasures. The rebels would have been besieged in the city, and this would have become a trap for them, as in the First Jewish War.

Anyone who expects Bar Kochba's rule over Jerusalem also needs a scenario of how it ended. Smallwood names various ancient authors who mention a (re-) conquest of Jerusalem by Hadrian: Appian , Justin, Eusebius and Hieronymus. According to Schäfer's analysis, Justin, Eusebius and Hieronymus, as Christian authors, are only interested in the fact that Jerusalem was finally lost to the Jews in their time. There remains Appian, who writes that Hadrian “destroyed” Jerusalem (κατέσκαψε); Here Schäfer argues that Hadrian thoroughly destroyed Jewish Jerusalem by rebuilding Aelia Capitolina and that there is therefore no need to think about an actual siege of the city by the Roman army during the Bar Kochba uprising.

Roman recapture of Judea

Hadrian probably went to the theater of war himself in the early stages of the uprising. Because of the heavy losses, he omitted the usual greeting in letters from army commanders to the Senate: “If you and your children are healthy, then it is good. We and the army are healthy. ”The uprising is called expeditio Iudaica in Roman inscriptions . This formulation was only used when the emperor was present in person.

Losses and drafts

On the Roman side, the two legions stationed in Judea (Legio X Fretensis, Legio VI Ferrata) fought with their auxiliary units. They suffered great losses at the beginning of the war because they did not adapt to the tactics of the rebels. Gaius Publius Marcellus, governor of the province of Syria , brought reinforcements from the north, including the Legio III Gallica . More legions sent vexillations: from the province of Arabia , the Legio III Cyrenaica , in Egypt , the Legio II Traiana from Moesia the Legio V Macedonica and the Legio XI Claudia , from Cappadocia the Legio XII Fulminata and from Pannonia the Legio X Gemina . Assuming that three legions fought at nominal strength and six legions each sent around 500 soldiers as reinforcements, Mor calculates that around 18,000 legionaries on the Roman side were involved in the suppression of the Bar Kochba uprising, plus the auxiliary units 27,500 fighters. Other historians expect far higher numbers. Bringmann assumes that 12 to 13 legions fought partly in full strength, partly with marching detachments on the Judean theater of war, that would be about a quarter of the entire Roman army. Eck assumes that 50,000 to 60,000 Roman soldiers were deployed in Judea.

Even Domaszewski had suspected that the rebels the Legio XXII Deiotariana destroyed, a theory which is represented today. Partly this is followed by further assumptions about the course of the war: The early victory brought the rebels control over the entire province except for cities such as Caesarea and Jerusalem; the legionary treasury had fallen into the hands of the rebels, and they overminted these coins. One thing is certain: the Legio XXII Deiotariana was stationed in Egypt in 119 and is missing from a list of legions from the time of Antoninus Pius. However, it is not known whether she took part in the fighting in Judea at all, whether it was dissolved or wiped out. From a difficult to read building inscription on the aqueduct of Caesarea it is concluded that this Legion 132/134 was stationed in Judea. Her name was subsequently deleted from the inscription, a Damnatio memoriae because of her inglorious role in the uprising. In 2011, Eck remained undecided: "The reconstruction must remain a hypothesis".

According to Eck, 15 military diplomas , which were issued in 160, prove the massive Roman losses at the beginning of the uprising. The recipients were veterans of the fleet stationed in Misenum on the Gulf of Naples. With a service period of 26 years, if one takes into account the life expectancy of a fleet soldier and the fact that only about one percent of all Roman diplomas have been received, there should have been a mass recruitment (dilectus) for the fleet in 135 . These recruits replaced naval soldiers who had been sent to reinforce the Legio X Fretensis as infantry in the insurrectionary area. “Such an extraordinary transfer of people who were not freeborn Roman citizens into a Roman civil legion has always been an emergency measure.” The scenario developed by Eck has met with wide acceptance despite the contradiction of Mor.

Four military diplomas, which go back to the same constitution of 160 and were issued to veterans from Syria Palestine, also make it possible to trace a forced recruitment initiated by the Roman military command in the province of Lycia et Pamphylia . Its aim was to integrate young soldiers into the auxiliary units fighting in Judea in 135. The Hecht Museum in Haifa has a particularly well-preserved specimen (photo). It was issued to the veteran Galata, son of Tata, who came from Sagalassus in Pisidia .

Dispatch of the Sextus Iulius Severus

The governor of Judea, Quintus Tineius Rufus, tried unsuccessfully to stifle the uprising through cruel reprisals. Birley believes he was deposed in 133 or 134. Cassius Dio writes that Hadrian sent his best generals into the insurrection area; but he only names the governor of Britain, Sextus Iulius Severus. This arrived in Judea in the course of 134, accompanied by units from Britain, including the Legio VI Victrix . The governors of the two neighboring provinces of Syria (Gaius Publius Marcellus) and Arabia Petraea (Haterius Nepos) were also involved as commanders in the fighting, because they were awarded the Ornamenta triumphalia together with Iulius Severus by Hadrian at the end of the war . Iulius Severus had a very successful career up to then. Moving from one large province to a smaller one would normally have been seen as a punishment, here it was an emergency measure. Iulius Severus came from the Aequum colony in Dalmatia . Both here and in the neighboring Burnum legionary camp, monuments were erected in his honor, and he is also known as the Legatus Augusti pro praetore of the province of Syria Palestine. He was governor of Judea until the end of the uprising. (The monument was erected after the Roman victory when he was honored for his services, and therefore includes the province's new name.)

The assumption of command by Iulius Severus brought the turning point in favor of the Romans, because he had experience with warfare in the mountains. He formed numerous small Roman combat groups that isolated the individual pockets of resistance, cut off their supplies and destroyed them. As the archaeological exploration of the wadis at the Dead Sea has shown, the rebels and their families withdrew to inaccessible caves in the final phase of the uprising and were starved there by the Roman army. In the heartland of the province of Judea, the legionaries systematically destroyed numerous Jewish villages; the ruins remained uninhabited for a longer period of time.

Case of Betar

Bar Kochba's last retreat was Betar ( Khirbet el-Yahud in Arabic , location ). The place had 1000 to 2000 inhabitants in peacetime and was unpaved. It was strategically located on a hilltop about 11 km southwest of Jerusalem, 700 m above sea level and 150 m above Wadi a-Sakha, which offered natural protection from attacks on three sides. On the south side, from where access was easily possible, the defenders had dug a 5 m deep and 15 m wide trench. Under time pressure, the rebels fortified the place with a temporary wall at least 5 m high with pillars and towers. It should serve as a line of defense for them.

A surrounding Roman wall, which cut off the water supply for the Betar crew, is partially visible in the area. In the south of the village there were the remains of two Roman camps and further camps in the vicinity, so that Oppenheimer reckons with 10,000 to 12,000 Roman legionaries and a corresponding number of Betar's defenders. The siege lasted several months, with the defenders of the fortress "being driven to extremes by hunger and thirst," as Eusebius of Caesarea wrote. The Roman army stormed Betar. It was all over so quickly that slingshot stones prepared by the defenders were no longer used.

The case of Betar is mentioned several times in rabbinical literature. Schäfer analyzes this "Bethar complex" with the result that the historical value of the texts in view of the course of the fighting is "extremely doubtful". On the other hand, Schäfer considers the stories surrounding the case of Betar to be very meaningful as an echo of a terrible event that was made literary by the following generations.

Victory celebrations

When the war was victoriously concluded from the Roman point of view in the first months of 136, the Roman imperial coins were silent, “as if there had been deep peace in the Middle East and, conversely, Rome had not been compelled to commit itself to it for more than three years Troops to fight down a revolt that is dangerous for the empire and its stability in the east, ”said Eck. A fragmentary inscription in Rome, which may have belonged to a small triumphal arch or a statue base, indicates a public honor of Hadrian by the Senate. This fragment was found right next to the Temple of Vespasian . Hadrian proclaimed himself as emperor for the second time, gave his generals the Ornamenta triumphalia , but renounced a triumphal procession. According to Eck, the Senate had a monumental arch of honor erected in honor of Hadrian near Tel Shalem; such a structure was occasionally erected outside Rome and Italy in memory of a Roman victory. He compares it to the arch of honor that was built for Emperor Trajan 116 outside of Dura Europos to commemorate the decisive victory over the Parthians. The Tel Shalem Arch of Honor is therefore directly linked to the suppression of the Bar Kochba uprising and the renewed proclamation of Hadrian as emperor.

There were reasons that Hadrian hardly used the victory in his portrayal of power: Vespasian and Titus had already staged their victory in the First Jewish War so strongly that a renewed, laboriously achieved submission of the same province in Rome could hardly make an impression. Hadrian's predecessor in office Trajan had emphasized the imperial victoriousness and strained the resources of the empire with wars of conquest. Hadrian on the one hand had to maintain his continuity with Trajan in order to legitimize his rule, but he did well not to seek comparison with his military successes. He therefore presented himself as a particularly caring princeps.

Consequences for the vanquished

The Roman province of Judea was renamed Syria Palestine and kept that name until the Arabs conquered it in the 7th century. Iudaea , however, was a Roman term and not a self-designation of the inhabitants. Both the Bar Kochba administration and the Mishnah used the term Israel instead . Renaming the province is an unusual process. The Roman Empire put down numerous revolts in its provinces, but in no other case was such a sanction applied. Eck suspects that Hadrian was responding to a wish of the non-Jewish population who suffered from the war and defined themselves as Syrian. For Birley, the renaming is also an indication that the Jewish population has become a minority as a result of the war in the province. The old name of the province initially remained in use, even officially on coins that date from the end of Hadrian's reign and address his visits to the provinces (so-called travel souvenir coins ). The personification of Judea on these coins, a female figure in Greek clothing, has no attributes typical of the province. At an altar she offers the emperor a libation with a patera and is accompanied by children with palm branches. One sees in the children an indication of the establishment of the colony.

Schwartz points out that Aelia Capitolina could only grow to a modest size as a city because its hinterland was completely destroyed in the war. It was a Roman colony with the typical public buildings and temples. There was no city wall. Architecturally highlighted gates marked the entrances: the Damascus Gate in the north, the Ecce Homo Arch in the east. There was probably also a west gate near what is now Jaffa Gate . The economic and religious center of the city was in what is now the Christian Quarter . The Herodian temple platform (according to Yaron Z. Eliav) was not included in Roman town planning because of its size and was located outside of Aelia as a ruin site. The fact that Jews were forbidden to enter Aelia Capitolina on the death penalty has been attested by several Christian ancient authors and is believed by many historians to be credible. Cassius Dio and the rabbinical sources make no mention of such a ban. It may not have been rigorously handled because there appears to have been an ascetic Jewish group (the "Zion Mourners") that settled in the city.

Rabbinic literature contains numerous references to persecution of the Jewish religion under Hadrian. Schäfer points out that the information becomes more detailed the further the texts are from the historical event of the Bar Kochba uprising. The Mishnah mentions a prohibition of circumcision and tefillin , the Tosefta a prohibition of the Torah , the megilla , the sukkah and the mezuzah . These are the oldest sources. According to Schäfer, these texts probably reflected a situation during or after the war in which it was dangerous to be recognized as a Jew. A repressive Roman policy in the insurgency is very likely. The governor of the province of Judea had the possibility to issue coercitio at his own discretion . That he used them to suppress the practice of the Jewish religion seems more plausible to Weikert than decrees across the empire.

Eck sees the information given by Cassius Dio with regard to the Jewish losses as historically accurate: 50 fortresses captured and 985 settlements destroyed, 580,000 dead and an unknown number who died from starvation, disease or fire. Almost all of Judea has become a wasteland. Schäfer considers the figures given by Cassius Dio to be exaggerated, but assumes high population losses and the economic structure in the insurrection area has been largely destroyed. The property of the killed or enslaved Jews was claimed as a bona vacantia for the imperial tax office and confiscated by fiscal procurators. However, not all of the property of Jews in the province was simply confiscated. The emperor had thus become the owner of a large, but scattered property, which was sold to private individuals. It appeared difficult to find buyers because of the depopulation of the province. Therefore, veterans were also resigned with land instructions.

In the period from the end of the Bar Kochba uprising to the Christianization of the empire, the Jewish population of Syria Palestine mainly lived in Upper and Lower Galilee, the area of Diospolis ( Lydda ), the Golan Heights and the semi-desert outskirts of Judea (for example the villages Zif, Eschtemoa and Susija south of Hebron), perhaps also in Joppa and other isolated places on the Mediterranean coast. The region, which was particularly hard hit by the war, may not have recovered until late antiquity.

Research history

Emil Schürer presented the first comprehensive account of the Bar Kochba uprising on the basis of all of the source material known at the time . It was reprinted several times and published in 1973 by Geza Vermes and Fergus Millar in an updated English version, which took into account the archaeological research results. Schürer's work was widely received. In 1946 the archaeologist Shmuel Yeivin presented a very material- rich account of the Bar Kochba uprising, which for a long time maintained the status of a standard work in Israel, but only appeared in Hebrew. According to Peter Schäfer , Yeivin mixed "solid information ... with imagination and speculation." Schäfer justifies his criticism, among other things, with the fact that Yeivin gives concrete geographical information on the advance of the Roman army and on various battles he has assumed.

The text finds from the Judah desert put knowledge of the Bar Kochba uprising on a new basis. A team from the École Biblique (Pierre Benoit, Józef T. Milik, Roland de Vaux ) explored the Wadi Murabbaʿat ; Milik published over 50 papyri in 1961. The Hebrew University carried out excavations in Nachal Chever in 1960/61 . Much of the evidence came from the time of the Bar Kochba uprising. As an excavator, however, Yigael Yadin left it with preliminary reports and popular scientific presentations. In his interpretation of the uprising, Yadin followed Yeivin's nationalist line.

Shimon Applebaum undertook a new approach in 1976 by including economic and military history. The Judaist Peter Schäfer evaluated the rabbinical sources for the Bar Kochba uprising in 1981. Until then, historians had often taken individual pieces of information from these texts and put them together in a kaleidoscope to create a picture of the Bar Kochba uprising.

Many coins of the Bar Kochba administration found their way into private collections from illegal excavations, so that nothing was known about the context of the find. In 1984 the numismatist Leo Mildenberg published a basic work on the coinage of the rebels. Based on the found coins, among other things, Israeli historians have been able to identify underground bases of operations of the Bar Kochba uprising (hiding complexes) since the 1990s .

The current discussion is about the interpretation of epigraphic sources, here Werner Eck and Menahem Mor represent contrary positions.

Reception in Zionism and in the State of Israel

Re-evaluation of the role of Bar Kochba in the 19th century

Bar Kochba was rated negatively in Jewish literature until the 19th century. But the modern national movement was looking for an example of military bravery that it could oppose to the traditional ideal of the brave martyr. The judgment of the historian Heinrich Graetz about Bar Kochba is symptomatic of this re-evaluation, which began with the Haskala : "... he was only fulfilled with the high task of regaining the freedom of his people, restoring the extinct splendor of the Jewish state and foreign rule ... to reject. Such an enterprising spirit, combined with high belligerent qualities, should have found more just recognition among posterity, even if its success was not favorable ... ”In 1892, Jewish students founded a Bar Kochba Association in Prague. Writers and composers took on the material.

Bar Kochba as an athlete

At the Second Zionist Congress in 1898 , Max Nordau coined the term “muscle Jewry”. He saw the task of Zionism in the physical education of the youth. For the first time since the “desperate struggle of the great Bar Kochba”, contemporary Judaism is faced with the challenge of demonstrating vitality, hope and longing for life. In 1900 he formulated: “Bar Kochba was a hero who did not want to see defeat. When victory left him, he knew how to die. Bar Kochba is the last embodiment of war-hard, gun-happy Judaism. To stand under Bar Kochba's invocation betrays ambition. But ambition is something gymnasts who strive for the highest level of development. "

As a result, numerous Jewish gymnastics clubs named themselves after Bar Kochba, although the figure of the ancient Jewish fighter initially remained pale. That changed through targeted Zionist remembrance work that used the growing prestige of sport. The holiday Lag baOmer (usually in May) was declared the “Day of Jewish Sport”, with the result that the memory of Bar Kochba gradually replaced the other festivities.

Lag baOmer as a bar-kochba festival

Since the beginning of Jewish immigration to Palestine , it has become a custom to light a fire at Lag BaOmer, because Bar Kochba's people would have given the signal for the uprising or celebrated their first victories in this way. Both paramilitary organizations and sports clubs celebrated the holiday with bonfires and hikes. Since 1916, the focus has been on offers for the youth, such as parades with torches and sports competitions, including archery. Because of this context, the bow and arrow were chosen as the symbol of the paramilitary youth organization Gadna . Palmach was founded at Lag ba Omer (1941) and the ordinance establishing the Israeli armed forces was issued (1948).

"Bar Kochba Syndrome"

The Israeli political scientist Yehoshafat Harkabi dealt in detail with the reception of the Bar Kochba uprising in modern Zionism and in the State of Israel . After he had already positioned himself accordingly, he published his views in book form in 1982 under the title: Vision instead of fantasy: lessons from the Bar Kochba uprising and political realism today . The title contrasted realistic visions of the future with desired political fantasies according to the motto: "The more unrealistic, the sooner it will happen." Harkabi saw this playful, risk-taking political style behind the fascination of many Israelis for the Bar Kochba uprising. Harkabi analyzed Israeli school books and children's literature, with the result that the historical facts would be glossed over and interwoven with legendary elements (example: Bar Kochba, who defeats a lion in the arena and then rushes to his fighters in Betar). The bloody end of the uprising is not discussed, played down or presented as a result of betrayal, not as a logical consequence of the unequal military possibilities of the war opponents. He quoted a song by Levin Kipnis that is sung in every kindergarten: “A man was in Israel, his name was Bar Kochba. A man, young and tall and with shining eyes. He was brave and called for freedom. The whole people loved him because he was so brave. "

Harkabi warned of Bar Kochba Syndrome: “The first condition of political wisdom is trying to gauge the results of a planned action. To admire the Bar Kochba uprising means to admire rebellion and heroism, detached from the resulting consequences. "

With his criticism of Bar Kochba, Harkabi had attacked a symbol of revisionist Zionism to which the older generation of this movement felt emotionally attached. These veterans were now members of the Likud .

State funeral for ancient bones

In 1960/61, Yigael Yadin's team explored the caves by the Dead Sea, where Bar Kochba's fighters and their families were starved by the Roman troops in the final phase of the war. The archaeologists found everyday objects of those people and letters from the historical figure Bar Kochba. In addition, human bones were recovered. Politicians from the religious party Agudat Yisrael called for these remains of Jews to be buried according to the Jewish rite. Yadin insisted that they were the bones of Romans; they should not be buried. The discussion about a burial and the appropriate place for it ebbed without practical consequences, but was taken up again years later by Shlomo Goren . This time he was able to secure the support of Menachem Begins , who ordered a state funeral.

On May 11, 1982, the holiday Lag baOmer, a burial with military honors took place on the hill above the site in Nahal Hever. Helicopters transported three identical coffins into the desert area. Although these were mostly the remains of women and children, they were generally referred to as the bones of Bar Kochba's fighters. The Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi Goren and the Sephardic Chief Rabbi Ovadja Josef were involved in the religious ceremony . The Prime Minister, the Cabinet and other government representatives attended this official tribute to Bar Kochba by the State of Israel. The Israeli people were able to watch the event on television. Begin recalled in his eulogy that it was Hadrian who renamed Judea Palestine - "a name that still haunts us". He addressed the deceased in an emotional way: “You glorious fathers, we have returned and we will not leave here.” A group of young demonstrators, dressed as Romans, parodied the ceremony, but was defeated by the police and the military pushed away.

The archaeologists around Yadin stayed away from the ceremony because they saw it as a symbolic attack on their work. The state burial for ancient bones thus became an expression of the competition between religious and archaeological interpretations of the past.

swell

Greek and Latin authors (selection)

- Cassius Dio : Roman history , transl. Otto Veh , 5 volumes, Artemis & Winkler, Düsseldorf 2007, ISBN 978-3-538-03103-6 , here volume 5: Epitome of the books 61-80.

- Justin Martyr : First Apology. In: Early Christian Apologists and Martyrs Acts Volume I, Translated by Gerhard Rauschen ( Library of the Church Fathers , 1st Row, Volume 12) Munich 1913. ( online ). Critical edition with English translation: Justin, Philosopher and Martyr: Apologies , ed. by Denis Minns and Paul Parvis, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2009. ISBN 978-0-19-954250-5 .

- Eusebius of Caesarea : Church history . Edited and introduced by Heinrich Kraft, translated by Philipp Haeuser , 2nd edition, Kösel, Munich 1981, ISBN 3-466-20023-7 .

Text finds from the Judah desert

-

Yigael Yadin (Ed.): The documents from the Bar Kokhba period in the cave of letters. Israel Exploration Society, Jerusalem

- Hebrew, Aramaic and Nabatean-Aramaic Papyri. Edited by Jonas C. Greenfield, Ada Yardeni, and Baruch A. Levine. Judean desert studies Vol. 3, 2002. Text and table volume. ISBN 965-221-046-3 .

- Greek papyri. Edited by Naphtali Lewis. Judean desert studies Vol. 2, 1989. ISBN 965-221-009-9 .

- The finds from the Bar Kokhba period in the Cave of Letters. Judean desert studies vol. 1, 1963.

literature

- Menahem Mor: The Second Jewish Revolt. The Bar Kokhba War, 132-136 CE. Brill, Leiden 2016, ISBN 978-90-04-31462-7 . ( Review )

- Christopher Weikert: From Jerusalem to Aelia Capitolina. The Roman policy towards the Jews from Vespasian to Hadrian (= Hypomnemata . Volume 200). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2016, ISBN 978-3-525-20869-4 .

- Werner Eck : domination, resistance, cooperation:.. Rome and the Jews in Judea / Palestine before the 4th century AD . In: Ernst Baltrusch , Uwe Puschner (Ed.): Jüdische Lebenswelten. From antiquity to the present (= civilizations & history. Volume 40). Peter Lang Edition, Frankfurt am Main et al. 2016, ISBN 3-631-64563-5 , pp. 31-52. ( online )

- Werner Eck: Judäa - Syria Palestine: The conflict of a province with Roman politics and culture (= Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism. Volume 157). Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2014. ISBN 978-3-16-153026-5 ( review ).

- William Horbury: Jewish was under Trajan and Hadrian. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2014, ISBN 978-0-521-62296-7 .

- Peter Schäfer : History of the Jews in antiquity. The Jews of Palestine from Alexander the Great to the Arab conquest. 2nd Edition. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2010, ISBN 978-3-16-150218-7 .

- Amos Kloner, Boaz Zissu : Underground Hiding Complexes in Israel and the Bar Kokhba Revolt. In: Opera Ipogea 1/2009, pp. 9-28. ( online )

- Hanan Eshel : The Bar Kochba Revolt, 132-135 . In: Steven T. Katz (Ed.): The Cambridge History of Judaism. Volume 4: The Late Roman - Rabbinic Period. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2006, ISBN 978-0-521-77248-8 . Pp. 105-127.

- Klaus Bringmann : History of the Jews in Antiquity. From the Babylonian exile to the Arab conquest. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-608-94138-X .

- Aharon Oppenheimer: Between Rome and Babylon: Studies in Jewish Leadership and Society (= Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism. Volume 108). Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2005, ISBN 3-16-148514-9 .

- Peter Schäfer (Ed.): The Bar Kokhba War reconsidered. New perspectives on the Second Jewish Revolt against Rome. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2003, ISBN 3-16-148076-7 ( review )

- Ra'anan Abusch: Negotiating Difference: Genital Mutilation in Roman Slave Law and the History of the Bar Kokhba Revolt. In: Peter Schäfer (Ed.): The Bar Kokhba War reconsidered. New perspectives on the second Jewish revolt against Rome. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2003, ISBN 3-16-148076-7 , pp. 71-91. ( online )

- Glen W. Bowersock : The Tel Shalem Arch and P. Nahal Hever / Seiyal 8 . In: Peter Schäfer (Ed.): The Bar Kokhba was reconsidered. New perspectives on the second Jewish revolt against Rome . Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2003, ISBN 978-3-16-148076-8 , pp. 171-180 ( digitized version ).

- Amos Kloner, Boaz Zissu : Hiding Complexes in Judaea. An Archaeological and Geographical Update on the Area of the Bar Kokhba Revolt. In: Peter Schäfer (Ed.): The Bar Kokhba War reconsidered. New perspectives on the second Jewish revolt against Rome. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2003, ISBN 3-16-148076-7 , pp. 181-216.

- Peter Kuhlmann : Religion and Memory. Emperor Hadrian's religious policy and its reception in ancient literature (= forms of memory. Volume 12). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2002, ISBN 3-525-35571-8 . ( Digitized version )

- E. Mary Smallwood: The Jews under Roman Rule: from Pompey to Diocletian: a study in political relations . 2nd Edition. Brill, Leiden 2001, ISBN 0-391-04155-X .

- Werner Eck: The Bar Kokhba Revolt: The Roman Point of View. In: Journal of Roman Studies 89 (1999), pp. 76-89.

- David Ussishkin: Archaeological Soundings at Betar, Bar-Kochba's Last Stronghold. In: Tel Aviv 20 (1993), pp. 66-97. ( online )

- Leo Mildenberg : The Coinage of the Bar Kokhba War. Verlag Sauerländer, Aarau 1984, ISBN 3-7941-2634-3 .

- Peter Schäfer: The Bar Kokhba uprising. Studies on the Second Jewish War against Rome. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 1981, ISBN 3-16-144122-2 .

- Peter Schäfer: R. Aqiva and Bar Kokhba. In: Studies on the history and theology of rabbinic Judaism. Brill, Leiden, 1978. ISBN 90-04-05838-9 , pp. 65-121.

- Shimon Applebaum : Prolegomena to the study of the second Jewish revolt (= British archaeological reports. Supplementary series. Volume 7). BAR, Oxford 1976

- Yigael Yadin: Bar Kochba. Archaeologists on the trail of the last prince of Israel. Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 1971, ISBN 3-455-08702-7 .

- Emil Schürer : From the destruction of Jerusalem to the fall of Barkocheba. In: History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ. Volume 1. 2nd edition. Leipzig 1890. pp. 539-589. ( Digitized version )

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Menahem Mor: The Second Jewish Revolt , Leiden 2016, p. 16 f. Likewise already: Michael Avi-Yonah : History of the Jews in the Age of the Talmud , Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 1962, p. 14.

- ↑ Christopher Weikert: From Jerusalem to Aelia Capitolina , Göttingen 2016, p. 261 f. Menahem Mor: The Second Jewish Revolt , Leiden 2016, pp. 186-189.

- ↑ Christopher Weikert: From Jerusalem to Aelia Capitolina , Göttingen 2016, p. 262.

- ↑ The new name is only clearly attested from the time of Antoninus Pius ; see Christopher Weikert: Von Jerusalem zu Aelia Capitolina , Göttingen 2016, p. 261. Menahem Mor: The Second Jewish Revolt , Leiden 2016, p. 248 f. 261; Mary Smallwood: The Jews under Roman Rule , 2nd ed. Leiden 2001, p. 431 f.

- ↑ Walter Ameling , Hannah M. Cotton , Werner Eck a . a. (Ed.): Corpus Inscriptionum Iudaeae / Palaestinae (CIIP). Volume 2: Caesarea and the Middle Coast. De Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2011, ISBN 978-3-11-022217-3 , No. 1276.

- ↑ Michael Avi-Yonah: The Caesarea Porphyry Statue Found in Caesarea. In: Israel Exploration Journal . Volume 20, 1970-1971, pp. 203-208; see also Menahem Mor: The Second Jewish Revolt , Leiden 2016, pp. 183-185; Christopher Weikert: From Jerusalem to Aelia Capitolina , Göttingen 2016, p. 261, note 175.

- ↑ Christopher Weikert: From Jerusalem to Aelia Capitolina , Göttingen 2016, p. 275.

- ^ Anthony R. Birley: Hadrian: The Restless Emperor. Routledge, London a. a. 1997, ISBN 0-415-16544-X , p. 233.

- ↑ Christopher Weikert: From Jerusalem to Aelia Capitolina , Göttingen 2016, pp. 99 f., 273 f.

- ^ Mary Smallwood: The Jews under Roman Rule , 2nd ed. Leiden 2001, p. 432 f.

- ↑ Christopher Weikert: From Jerusalem to Aelia Capitolina , Göttingen 2016, pp. 99 f., 270 f. The newly found fragment completes CIIP I 2, 715. See EDCS-54900616 .

- ↑ Christopher Weikert: From Jerusalem to Aelia Capitolina , Göttingen 2016, pp. 99 f., 269–271.

- ↑ Klaus Bringmann: History of the Jews in antiquity. Stuttgart 2005, p. 285.

- ↑ Klaus Bringmann: History of the Jews in Antiquity , Stuttgart 2005, p. 275.

- ↑ Christopher Weikert: From Jerusalem to Aelia Capitolina , Göttingen 2016, pp. 99 f., 279–284. William Horbury: Jewish war under Trajan and Hadrian , Cambridge 2014, p. 310 f.

- ↑ Peter Kuhlmann: Religion and Remembrance , Göttingen 2002, p. 133. See Historia Augusta: Vita Hadriani 14.2 .

- ↑ Emil Schürer: From the Destruction of Jerusalem to the Fall of Barkocheba. Leipzig 1890, p. 566 f. Mary Smallwood: The Jews under Roman Rule , 2nd ed. Leiden 2001, p. 431.

- ↑ Peter Kuhlmann: Religion and Remembrance , Göttingen 2002, p. 134 f. See Modestinus, Dig. 48.8.11.1.

- ^ Ra'anan Abusch: Negotiating Difference , Tübingen 2003, p. 85.

- ↑ Ra'anan Abusch: Negotiating Difference , Tübingen 2003, pp. 74-76. See Ulpian , Dig. 48.8.4.2.

- ↑ Christopher Weikert: From Jerusalem to Aelia Capitolina , Göttingen 2016, p. 302.

- ↑ Christopher Weikert: From Jerusalem to Aelia Capitolina , Göttingen 2016, p. 243.

- ↑ Abraham Schalit: King Herod: The man and his work. Walter de Gruyter, 2nd edition Berlin / New York 2001, p. 192 f.

- ↑ Menahem Mor: The Second Jewish Revolt , Leiden 2016, p. 39.

- ↑ Menahem Mor: The Second Jewish Revolt , Leiden 2016, p. 41. Likewise Christopher Weikert: Von Jerusalem zu Aelia Capitolina , Göttingen 2016, p. 244. The opposing position is under the keyword local unrest by Isaac and Oppenheimer, based on Applebaum's work on the social history of Judea.

- ↑ Menahem Mor: The Second Jewish Revolt , Leiden 2016, pp. 173-179.

- ↑ Glen Warren Bowersock: The Tel Shalem Arch and P. Nahal Hever / Seiyal 8, Tübingen 2003, p. 177.

- ↑ Glen Warren Bowersock: The Tel Shalem Arch and P. Nahal Hever / Seiyal 8, Tübingen 2003, p. 180.

- ↑ Werner Eck: Caearea Maritima - a Roman city? In: Judäa - Syria Palästina , Tübingen 2014, pp. 150–162, here p. 157.

- ↑ Christopher Weikert: From Jerusalem to Aelia Capitolina , Göttingen 2016, pp. 274–276.

- ↑ Shimon Applebaum: Prolegomena to the study of the second Jewish revolt , Oxford 1976, pp. 12,14.

- ↑ Shimon Applebaum: Prolegomena to the study of the second Jewish revolt , Oxford 1976, p. 63.

- ↑ Christopher Weikert: From Jerusalem to Aelia Capitolina , Göttingen 2016, p. 303 f. Menahem Mor: The Second Jewish Revolt , Leiden 2016, p. 81.

- ↑ For example Michael Avi-Yonah: History of the Jews in the Age of the Talmud, in the days of Rome and Byzantium , Berlin 1962, p. 14. Akiba, "the spiritual leader of that generation", and Bar Kochba as head of administration and military leaders together the "leadership of the insurgents". Ibid., P. 64: The actually apolitical mass of the population joined the Bar Kochbas camp under the influence of Akiba.

- ^ Werner Eck: Rule, Resistance, Cooperation , Frankfurt / M. 2016, p. 50.

- ^ Seth Schwarz: Imperialism and Jewish Society: 200 BCE to 640 CE Princeton 2001, ISBN 978-0-691-11781-2 . Pp. 103 f., 109 f.

- ↑ Peter Schäfer: The Bar Kokhba uprising: Studies on the second Jewish war against Rome , Tübingen 1986, p. 49. Peter Schäfer: History of the Jews in antike , Tübingen 2010, p. 176 f.

- ↑ Peter Schäfer: The Bar Kokhba uprising: studies on the second Jewish war against Rome , Tübingen 1986, p. 45 f. Seth Schwarz: Imperialism and Jewish Society: 200 BCE to 640 CE Princeton 2001, ISBN 978-0-691-11781-2 , p. 109 f. See t Shab 15 (16), 9.

- ^ Benjamin Isaac : Military Diplomas and Extraordinary Levies for Campaigns . In: The Near East Under Roman Rule: Selected Papers . Brill, Leiden et al. 1998, pp. 427-436, here p. 433 f. Christopher Weikert: From Jerusalem to Aelia Capitolina , Göttingen 2016, p. 316 f. See CIL XVI 107.

- ↑ Menahem Mor: The Second Jewish Revolt , Leiden 2016, p. 394. See Cassius Dio 69,13,2 .

- ↑ Menahem Mor: The Second Jewish Revolt , Leiden 2016, p. 382. William Horbury: Jewish war under Trajan and Hadrian , Cambridge 2014, p. 349.

- ^ Werner Eck: Hadrian, the Bar Kokhba revolt, and the Epigraphic Transmission. In: Judäa - Syria Palästina , Tübingen 2014, pp. 212–228, here p. 214.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 69,12,2

- ↑ Peter Kuhlmann: Religion and Remembrance , Göttingen 2002, p. 66. Hanan Eshel: The Bar Kochba Revolt, 132–135 , Cambridge 2006, p. 108.

- ^ Anthony R. Birley: Hadrian: The Restless Emperor. Routledge, London a. a. 1997, ISBN 0-415-16544-X , p. 259.

- ↑ Hanan Eshel: The Bar Kochba Revolt, 132-135 , Cambridge 2006, p. 105.

- ↑ Aharon Oppenheimer: Between Rome and Babylon , Tübingen 2005, p. 206 f.

- ↑ Amos Kloner, Boaz Zissu: Hiding Complexes in Judaea. An Archaeological and Geographical Update on the Area of the Bar Kokhba Revolt , Tübingen 2003, p. 186 f.

- ^ Hans-Peter Kuhnen: Palestine in Greco-Roman times , CH Beck, Munich 1990, ISBN 3-406-32876-8 . P. 160. Similarly, Seth Schwartz: The Ancient Jews from Alexander to Muhammad. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2014, ISBN 978-1-107-66929-1 , p. 94. The enclosures are difficult to date and it is a priori unlikely that they would always be related to the Bar Kochba uprising.

- ^ Werner Eck: Rule, Resistance, Cooperation . Frankfurt / M. 2016, p. 47.

- ↑ Menahem Mor: The Second Jewish Revolt , Leiden 2016, p. 166 f.

- ↑ Hanan Eshel: The Bar Kochba Revolt, 132-135 , Cambridge 2006, p. 112.

- ↑ Menahem Mor: The Second Jewish Revolt , Leiden 2016, p. 43.

- ^ Werner Eck: Rule, Resistance, Cooperation . Frankfurt / M. 2016, p. 45.

- ↑ Hanan Eshel: The Bar Kochba Revolt, 132-135 , Cambridge 2006, p. 105.

- ↑ Klaus Bringmann: History of the Jews in Antiquity , Stuttgart 2005, p. 277.

- ↑ Leo Mildenberg: The Bar Kochba War in the light of coinage. In: Hans-Peter Kuhnen: Palestine in Greco-Roman times , CH Beck, Munich 1990, ISBN 3-406-32876-8 , Göttingen 2016, pp. 357-366, here p. 358.

- ^ Ya'aḳov Meshorer: Ancient Jewish Coinage , Volume 2: Herod the Great Through Bar Cochba , New York 1982, p. 135.

- ↑ Leo Mildenberg: The Bar Kochba War in the light of coinage. In: Hans-Peter Kuhnen: Palestine in Greco-Roman Times , CH Beck, Munich 1990, ISBN 3-406-32876-8 ., Göttingen 2016, pp. 357-366, here p. 362.

- ^ Martin Goodman: Coinage and Identity: The Jewish Evidence. In: Christopher Howgego et al. (Ed.): Coinage and Identity in the Roman Provinces , Oxford University Press, Oxford 2007, pp. 163–166, here p. 166.

- ↑ Christopher Weikert: From Jerusalem to Aelia Capitolina , Göttingen 2016, p. 316 and note 392.

- ↑ Peter Schäfer: History of the Jews in antiquity , Tübingen 2010, p. 177. Hebrew בן ben and Aramaic בר bar both mean “son”.

- ↑ Peter Schäfer: History of the Jews in antiquity , Tübingen 2010, p. 178.

- ^ Aharon Oppenheimer: Between Rome and Babylon , Tübingen 2005, p. 222.

- ↑ Peter Schäfer: The Bar Kokhba uprising: Studies on the second Jewish war against Rome , Tübingen 1986, p. 75 f. See P. Yadin 57, P. Yadin 52.

- ↑ Peter Schäfer: The Bar Kokhba uprising: Studies on the second Jewish war against Rome , Tübingen 1986, p. 59 f. See Justin, Apol. I, 31.6.

- ↑ Leo Mildenberg: The Bar Kochba War in the light of coinage. In: Hans-Peter Kuhnen: Palestine in Greco-Roman times , CH Beck, Munich 1990, ISBN 3-406-32876-8 ., Göttingen 2016, pp. 357-366, here p. 358.

- ↑ Peter Schäfer: Geschichte der Juden in der Antike , Tübingen 2010, p. 181. Menahem Mor: The Second Jewish Revolt , Leiden 2016, pp. 414-418, rejects the messianic interpretation of stars and grapes on coinage .

- ↑ Klaus Bringmann: History of the Jews in antiquity. Stuttgart 2005, p. 279.

- ↑ Hanan Eshel: The Bar Kochba Revolt, 132-135 , Cambridge 2006, p. 115. Also Werner Eck: Rom and Judaea , Tübingen 2007, p. 115.

- ↑ Peter Schäfer: History of the Jews in antiquity , Tübingen 2010, p. 187.

- ↑ Peter Schäfer: The Bar Kokhba uprising: studies on the second Jewish war against Rome , Tübingen 1986, p. 57 f.

- ↑ Peter Schäfer: The Bar Kokhba uprising: studies on the second Jewish war against Rome , Tübingen 1986, p. 72 f.

- ↑ Peter Schäfer: History of the Jews in antiquity , Tübingen 2010, p. 183 f. See P. Mur 24b. Anthony R. Birley: Hadrian: The Restless Emperor. Routledge, London a. a. 1997, ISBN 0-415-16544-X , p. 272.

- ^ Peter Schäfer: History of the Jews in antiquity , Tübingen 2010, p. 182.

- ↑ William Horbury: Jewish war under Trajan and Hadrian , Cambridge 2014, p. 356. Critical to the identification of the two El'azar are Menahem Mor: The Second Jewish Revolt , Leiden 2016, p. 430 f. and Peter Schäfer: The Bar Kokhba Uprising: Studies on the Second Jewish War against Rome , Tübingen 1986, p. 99 f.

- ↑ Yehoshafat Harkabi: The Bar Kochba Syndrome: Risk and Realism in International Politics , Chappaqua 1983 S. 97th

- ^ Anthony R. Birley: Hadrian: The Restless Emperor. Routledge, London a. a. 1997, ISBN 0-415-16544-X , p. 270.

- ↑ Peter Schäfer: R. Aqiva and Bar Kokhba , Leiden 1978, p. 73 f. 78 f. 86.

- ↑ Peter Schäfer: R. Aqiva and Bar Kokhba , Leiden 1978, p. 86ff. See TJ Taanit, 4,68d., EchaR 2,4, Echa RB p. 101. Menahem Mor: The Second Jewish Revolt , Leiden 2016, p. 405f. Christopher Weikert: From Jerusalem to Aelia Capitolina , Göttingen 2016, p. 311. Quotation: the shortest form of the Messiah proclamation, Midrash Echa Rabbati (ed. Salomon Buber), in the translation by Weikert.

- ↑ Wolfgang Kraus, Martin Karrer (Ed.): Septuaginta Deutsch , Stuttgart 2009, p. 162.

- ↑ Peter Schäfer: R. Aqiva and Bar Kokhba , Leiden 1978, p. 89 f.

- ↑ Christopher Weikert: From Jerusalem to Aelia Capitolina , Göttingen 2016, p. 309 f.

- ^ Hans-Peter Kuhnen: Palestine in Greco-Roman times , CH Beck, Munich 1990, ISBN 3-406-32876-8 . P. 159.

- ^ Peter Schäfer: History of the Jews in antiquity , Tübingen 2010, p. 188. Anthony R. Birley: Hadrian: The Restless Emperor. Routledge, London a. a. 1997, ISBN 0-415-16544-X , p. 272.

- ↑ Amos Kloner, Boaz Zissu: Hiding Complexes in Judaea. An Archaeological and Geographical Update on the Area of the Bar Kokhba Revolt , Tübingen 2003, p. 199.

- ↑ Hanan Eshel: The Bar Kochba Revolt, 132-135 , Cambridge 2006, p. 113 f.

- ↑ Peter Schäfer: History of the Jews in antiquity , Tübingen 2010, p. 188.

- ^ Mary Smallwood: The Jews under Roman Rule , 2nd ed. Leiden 2001, p. 443.

- ↑ Hanan Eshel, Magen Broshi, Timothy AJ Jull: Four Murabbaʿat Papyri and the Alleged Capture of Jerusalem by Bar Kokhba. In: Ranon Katzoff, David Schaps (eds.): Law in the Documents of the Judaean Desert , Brill, Leiden / Boston 2005, pp. 46–50. See P. Mur 22,25,29,30.

- ↑ Hanan Eshel: The Bar Kochba Revolt, 132-135 , Cambridge 2006, p. 115. Also Werner Eck: Rom and Judaea , Tübingen 2007, p. 116.

- ↑ Menahem Mor: The Second Jewish Revolt , Leiden 2016, p. 437.

- ^ Mary Smallwood: The Jews under Roman Rule , 2nd ed. Leiden 2001, p. 444. See Appian, Syr. 50; Justin Mart., Dial. 108.3; Eusebius, Hist. Eccl. vi, 18.10; Hieronymus, In Ezech. ii.5 to Ez 5.1-4 [1] .

- ↑ Peter Schäfer: The Bar Kokhba Uprising: Studies on the Second Jewish War against Rome , Tübingen 1986, pp. 81–85.

- ^ Anthony R. Birley: Hadrian: The Restless Emperor. Routledge, London a. a. 1997, ISBN 0-415-16544-X , p. 272. Werner Eck: Dominion, resistance, cooperation . Frankfurt / M. 2016, p. 45.

- ↑ Werner Eck: The Bar Kochba uprising of the years 132-136 and its consequences for the province of Syria Palestine. In: Judäa - Syria Palestine , Tübingen 2014, pp. 229–244, here p. 237. See Cassius Dio 69,14,2 .

- ↑ Christopher Weikert: From Jerusalem to Aelia Capitolina , Göttingen 2016, p. 324.

- ^ Anthony R. Birley: Hadrian: The Restless Emperor. Routledge, London a. a. 1997, ISBN 0-415-16544-X , p. 268.

- ↑ Menahem Mor: The Second Jewish Revolt , Leiden 2016, pp. 324–327.

- ^ Werner Eck: Rule, Resistance, Cooperation . Frankfurt / M. 2016, p. 45. Klaus Bringmann: History of the Jews in Antiquity. Stuttgart 2005, p. 283.

- ↑ Werner Eck: Rom and Judaea , Tübingen 2007, p. 117.

- ↑ Critical to this: Peter Schäfer: Der Bar Kokhba-Aufstand , Tübingen 1981, p. 12f.

- ^ Aharon Oppenheimer: Between Rome and Babylon , Tübingen 2005, p. 220.

- ↑ Christopher Weikert: From Jerusalem to Aelia Capitolina , Göttingen 2016, p. 323 f. Menahem Mor: The Second Jewish Revolt , Leiden 2016, p. 33 ff.

- ↑ Walter Ameling , Hannah M. Cotton , Werner Eck a . a. (Ed.): Corpus Inscriptionum Iudaeae / Palaestinae (CIIP). Volume 2: Caesarea and the Middle Coast. De Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2011, ISBN 978-3-11-022217-3 , no.1201.

- ↑ Werner Eck: The Bar Kochba uprising of the years 132-136 and its consequences for the province of Syria Palestine. In: Judäa - Syria Palästina , Tübingen 2014, pp. 229–244, here p. 232.

- ↑ Werner Eck: The Bar Kochba uprising of the years 132-136 and its consequences for the province of Syria Palestine. In: Judäa - Syria Palästina , Tübingen 2014, pp. 229–244, here p. 231.

- ↑ Christopher Weikert: From Jerusalem to Aelia Capitolina , Göttingen 2016, p. 323. Christian Mann : Military and warfare in antiquity , in Encyclopedia of Greco-Roman antiquity , volume. 9, Oldenbourg, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-486-59682-3 , p. 114 f. Against Menahem Mor: The Second Jewish Revolt , Leiden 2016, pp. 199-201; 338 ff. Mor's main argument is that the number of military diplomas received is the product of coincidences in tradition and does not allow any conclusions to be drawn about the number of recruits.

- ↑ Werner Eck: A diploma for the troops of Syria Palestine from the year 160: A reflex on the Bar Kochba revolt. In: Judäa - Syria Palästina , Tübingen 2014, pp. 256–265.

- ^ Anthony R. Birley: Hadrian: The Restless Emperor. Routledge, London a. a. 1997, ISBN 0-415-16544-X , p. 274.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 69,13,2

- ↑ Shimon Applebaum: Tineius Rufus and Julius Severus , p. 121 f. In: Judaea in Hellenistic and Roman Times. Historical and Archaeological Essays (= Studies in Judaism in late antiquity , Volume 40). Brill, Leiden et al. 1989, ISBN 9-004-08821-0 , pp. 117-123.

- ^ Werner Eck: Rule, Resistance, Cooperation . Frankfurt / M. 2016, p. 45 f.

- ↑ Werner Eck: The Bar Kochba uprising of the years 132-136 and its consequences for the province of Syria Palestine. In: Judäa - Syria Palästina , Tübingen 2014, pp. 229–244, here p. 239.

- ↑ Menahem Mor: The Second Jewish Revolt , Leiden 2016, p. 352 f.

- ^ Werner Eck: Hadrian, the Bar Kokhba revolt, and the Epigraphic Transmission. In: Judäa - Syria Palästina , Tübingen 2014, pp. 212–228, here pp. 226 f.

- ↑ Menahem Mor: The Second Jewish Revolt , Leiden 2016, p. 491. See Cassius Dio 69, 13, 2-3 .

- ↑ Werner Eck: The Bar Kochba uprising, the imperial Fiscus and the veterans' supply. In: Judäa - Syria Palästina , Tübingen 2014, pp. 275–283, here pp. 277 f.

- ^ A b David Ussishkin: Archaeological Soundings at Betar, Bar-Kochba's Last Stronghold , 1993, p. 94.

- ↑ Menahem Mor: The Second Jewish Revolt , Leiden 2016, p. 215.

- ↑ Menahem Mor: The Second Jewish Revolt , Leiden 2016, pp. 214-216. William Horbury: Jewish war under Trajan and Hadrian , Cambridge 2014, p. 399. See Eusebius, Hist. Eccl. 4,6.3.

- ↑ David Ussishkin: Archaeological Soundings at Betar, Bar-Kochba's Last Stronghold , 1993, p. 96. (A finding that Shmuel Yeivin had described in his standard work on the Bar-Kochba uprising as a Roman siege ramp turned out to be a modern stone embankment .) Aharon Oppenheimer: Between Rome and Babylon , Tübingen 2005, p. 307 f.

- ↑ Peter Schäfer: The Bar Kokhba uprising , Tübingen 1981, p. 192 f.

- ↑ Werner Eck: The Bar Kochba uprising of the years 132-136 and its consequences for the province of Syria Palestine. In: Judäa - Syria Palästina , Tübingen 2014, pp. 229–244, here p. 229.

- ↑ Christopher Weikert: From Jerusalem to Aelia Capitolina , Göttingen 2016, p. 338.

- ^ Werner Eck: Hadrian, the Bar Kokhba revolt, and the Epigraphic Transmission. In: Judäa - Syria Palästina , Tübingen 2014, pp. 212–228, here p. 221.

- ↑ Peter Schäfer: History of the Jews in antiquity , Tübingen 2010, p. 191.

- ^ Werner Eck: Hadrian, the Bar Kokhba revolt, and the Epigraphic Transmission. In: Judäa - Syria Palästina , Tübingen 2014, pp. 212–228, here p. 217.

- ↑ Christopher Weikert: From Jerusalem to Aelia Capitolina , Göttingen 2016, p. 340 f. Gunnar Soul Day : Trajan, Hadrian and Antoninus Pius. Interpretation patterns and perspectives. In: Aloys Winterling (Ed.): Between structural history and biography. Problems and perspectives of a new Roman imperial history from Augustus to Commodus. Oldenbourg, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-486-70454-9 , pp. 295-315, here p. 309.

- ↑ Christopher Weikert: From Jerusalem to Aelia Capitolina , Göttingen 2016, p. 335.