Lichen planus

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| L43 | Lichen planus (excl. Lichen pilaris) |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

The Lichen Planus (short: Lichen planus or lichen planus , including: lichen ) is a non-contagious skin disease of unknown etiology, preferably in adulthood occurs. The typical lesions are polygonal and flat, reddish-purple papules or plaques, which usually appear on the flexors of the forearms, the extensor sides of the lower legs and above the sacrum and are accompanied by severe itching.

In addition to this classic form of lichen planus, there are numerous other manifestations of the disease that can also manifest themselves on the hairy skin of the head (lichen planopilaris) , the fingernails (lichen unguis) and the mucous membranes (lichen mucosae) . Some of these forms are linked to an increased risk of skin cancer.

The disease lasts for up to two years - possibly in phases - and then subsides. Creams containing cortisone are usually used for treatment to shorten the course of the disease and reduce long-term effects.

distribution

Information on the prevalence of lichen planus in the general population fluctuates between less than 1% and 5%. Women and men are largely equally affected, although some studies have shown a higher incidence in women. The peak of the disease is in the third to sixth decade of life. Nevertheless, children can also get sick; boys are affected twice as often as girls.

root cause

The causes of the disease are largely unknown, various factors are discussed:

Genetics: rare familial cases indicate a genetic predisposition. Carriers of certain class II HLA genes responsible for regulating the individual immune response are more frequently affected by the disease than others, with different HLA characteristics being associated with different variants of the lichen planus.

Autoimmunity : the inflammation pattern indicates an autoimmune mechanism against keratinocytes (horn-forming cells of the epidermis). In addition, there is an increased incidence of lichen planus together with other diseases that are caused by a disturbed immune response.

Infectious diseases: infections e.g. B. Herpes viruses or the hepatitis C virus are discussed as triggers of the lichen planus. For the hepatitis C virus, there seems to be a stronger association with individual variants of the lichen planus, which, depending on the frequency of HCV infections, is more or less important in certain regions of the world.

Medicines and other substances: certain drugs are suspected of causing the disease. Individual cases of lichen planus after exposure to toluene have been described.

Disease emergence

Cytotoxic T lymphocytes , stimulated by the above-mentioned factors, migrate into the dermis . Here they cause an inflammatory reaction that leads to the death of keratinocytes in the lower cell layers of the epidermis (upper skin).

Clinical appearance

The classic cutaneous lichen planus causes polygonal and flat, occasionally centrally indented, reddish-purple papules or plaques. These occur in groups and possibly confluent on both sides on the flexor sides of the wrists and forearms, the extensor sides of the lower legs and ankles and in the region above the sacrum. On their surface, the papules show a fine white streaky pattern, called Wickham striae, which is best seen when examining with a dermatoscope .

In most cases, the skin changes are accompanied by severe itching. The Koebner phenomenon is positive: new lesions can be triggered by scratching the skin and then develop along the scratch track.

The disease usually begins in the limbs and spreads - possibly in stages - within several months, only to subside by itself after up to two years. As a residual condition, post- inflammatory hyperpigmentation (inflammation-related increased pigmentation) can remain in the areas where the skin changes had previously occurred.

Further manifestations

Numerous variants of lichen planus have been described, which differ from the classic clinical picture in their clinical presentation and in some cases also in terms of their distribution in the population. They can be grouped according to the configuration and appearance as well as the distribution pattern of the lesions and the structure affected by them (skin, skin appendages, mucous membrane), with overlapping between the categories.

Configuration and appearance of the lesions

Lichen planus hypertrophicus (Lichen planus verrucosus)

Strongly pigmented, reddish-purple or reddish-brown lesions with hyperkeratosis (excessive cornification) of the epidermis, which are often accompanied by very severe itching, form particularly above the shins and the interphalangeal joints ( pontic joints ) of the fingers . This variant occurs more frequently in the context of familial diseases and makes up about a quarter of lichen planus cases in children. The course is often chronic; scarring and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation are relatively common. There is also an increased risk for patients of developing squamous cell carcinoma (white skin cancer) as a result of the disease .

Ulcerative lichen planus

Ulcerative lesions (associated with a defect in the epidermis) develop primarily on the hands, fingers, soles of the feet and toes. Furthermore, ulcerous lesions occur in the context of a lichen planus mucosae. This variant of the lichen planus can also be associated with an increased risk of squamous cell carcinoma.

Vesicobular lichen planus

Rare variant in which the degeneration of the keratinocytes in the lowest cell layer of the epidermis leads to the formation of subepidermal blisters within typical skin lesions. The clinical symptoms are considered to be milder than those of classic lichen planus. It can be differentiated from lichen planus pemphigoides by means of direct and indirect immunofluorescence .

Lichen planus atrophicus

Rare variant that most likely represents the late stage of hypertrophic lichen planus. There are a few well-circumscribed whitish-blue plaques with a sunken center on the trunk and lower limbs. In the differential diagnosis, the lesions can be difficult to differentiate from lichen sclerosus .

Annular lichen planus

Also rare variant with primarily ring-shaped lesions. Annular lesions with an atrophic center are found in the context of a lichen planus mucosae on the cheek mucosa or the mucous membranes of the male genitals.

Perforating lichen planus

This variant can be detected histologically (in the microscopic examination of tissue samples from the skin lesions), which shows that hyaline bodies are discharged through the epidermis.

Invisible lichen planus

Without visible skin changes, patients suffer from itching. Examination with a Wood lamp or a tissue sample reveals changes typical of lichen planus.

Distribution pattern of the lesions

Localized and generalized lichen planus

Lesions can occur localized in a single skin area, often affecting the wrists, lower legs, and lower back. In the generalized form, there is extensive involvement of several skin areas, in about two thirds of the cases with involvement of the oral mucosa.

Lichen planus linearis

Skin lesions occur along a line, e.g. B. along a scratch track (Koebner phenomenon). This distribution pattern, also known as zosteriform, occurs z. B. in the context of a localized lichen planus and especially in children.

Lichen planus inversus

Skin changes appear in atypical places and intertriginous (in areas where opposing skin surfaces touch).

Lichen planus exanthematicus

In about a third of lichen planus cases, a rash-like appearance of lichen planus-typical lesions all over the body appears within a week, which reach their maximum extent after two to 16 weeks.

Lichen planus pigmentosus (Erythema dyschronicum perstans)

Sharply demarcated and heavily pigmented, violet-brown papules can be seen, especially on light-exposed skin of the face and neck, but an inverse form with involvement of the flexors or intertriginous is also possible. This variant occurs with the same gender distribution, especially in dark-skinned people in the tropics. In some cases there is itching and the course is often intermittent.

Actinic lichen planus

This form of lichen planus, also known as summertime actinic lichenoid eruption or lichenoid melanodermatosis , affects the light-exposed skin of the face - especially the lateral forehead -, the neck, the backs of the hands and forearms. In spring and summer in particular, bluish-brown, partly confluent, annular (ring-shaped) lesions with a sunken center and sometimes hypopigmented (light-colored) border, which are associated with slight itching. The Koebner phenomenon is negative. This variant occurs more frequently in the Middle East and Egypt, preferably in the second and third decades of life. Women get sick more often than men. Some authors equate this form with the lichen planus pigmentosus.

Affected structure

The classic lichen planus of the skin can include skin appendages such as hair, nails and ducts of the sweat glands and lead to characteristic changes here too. Mucous membranes can be affected both in the context of a generalized lichen planus and without simultaneous skin involvement.

Lichen planopilaris

This form of lichen planus occurs on the hairy skin of the head or other body regions and involves the hair follicles . The lesions are often asymptomatic, but can also be itchy, painful, or burning. The mostly chronic course leads to scarring alopecia on the scalp . Graham Little Syndrome is a special form .

Lichen unguis

In around 10% of cases, the lichen planus is associated with involvement of the nail apparatus, especially in the context of ulcerative lichen planus, which often manifests itself on the hands and feet. Longitudinal grooves or thinning of the nail plate, splintering of the nail ends or pterygium formation occur. Subungal (under the nail) hyperkeratosis and loss of the nail are rather rare. The course is often chronic and recurrent.

Lichen planoporitis

Skin lesions occur in association with the acrosyringia (ducts of the sweat glands). This variant is more histologically understandable, possibly an accompanying squamous epithelial metaplasia of the duct epithelium.

Lichen planus mucosae

Mucosal manifestations of the lichen planus occur most frequently in the oral cavity (oral lichen planus) or in the genital area (lichen planus genitalis). Here, net-like, white lesions appear, in the genital area also annular or bullous lesions. The mucous membranes of the esophagus, the nasopharynx, the eyes and ears, the lower urinary tract and the anal area can also be affected.

Overlap Syndromes

Lichen planus pemphigoides

This rare variant is considered to be a combined clinical picture: Patients who have lesions typical of lichen planus on the one hand develop large, tense blisters in normal or erythematous skin elsewhere, as are typical of bullous pemphigoid. Clinically, histologically and immunologically, the lesions each have characteristics characteristic of one or the other clinical picture. The differentiation from vesicobulosic lichen planus, in which smaller blisters occur within lichen planus-typical papules, may only be possible using immunofluorescence.

Complications

In addition to the often severe itching and the pigment disorders that occur, especially in dark-skinned patients, after the lesions have healed, the affected areas of skin can become scarred. On the scalp, this leads to the loss of hair; if the nail system is involved, it may result in the loss of the affected fingernail or toenail. Some forms of lichen planus are associated with an increased risk of squamous cell carcinoma.

diagnosis

In addition to the anamnesis (taking the medical history), the diagnosis includes a clinical examination, whereby manifestations in the oral cavity and in the genital area should also be inquired about and examined.

When examining with a dermatoscope , best after application of oil or water, fine white Wickham striae on a reddish background and blood vessels in the edge area of the lesions can be seen on the surface of the lesions.

If the diagnosis cannot be clinically confirmed, a biopsy (tissue sample) can be taken from abnormal skin for examination under the microscope. Particularly in the case of erosive or ulcerative lesions (associated with a substance defect in the epidermis), sampling is recommended from their marginal area in order to capture assessable parts of the epidermis and to minimize the risk of an ulcer-inflammatory superimposition of the disease-specific histomorphological features of the lichen planus. A biopsy examination should also be carried out in the case of permanent lesions, particularly those that persist under therapy. If a second tissue sample is taken from the lesional skin and sent unfixed to the laboratory, it can be examined using direct immunofluorescence. The examination method is not used in the standard diagnosis of lichen planus, but in the case of vesicobuloid lesions it can facilitate the differential diagnosis to other blistering skin diseases.

If there is a corresponding clinical suspicion, e.g. B. Due to swallowing difficulties, an endoscopic examination should be performed to determine whether the esophagus is involved. An HCV test may also be performed for patients from regions with high HCV prevalence.

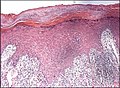

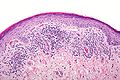

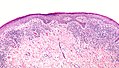

pathology

Histologically, hypertrophy (increase in tissue) or atrophy (tissue shrinkage) of the epidermis with acanthosis, often described as sawtooth-like, can be seen . Hyperkeratosis is particularly common in hypertrophic lichen planus. Characteristic is a wedge-shaped hypergranulosis (widening of the stratum granulosum of the epidermis) centered mostly around the acosyringia , the histological correlate of the clinically visible Wickham striae. In the lowest cell layer of the epidermis there is a vacuolar degeneration of the keratinocytes and keratinocyte necrosis (English civatte bodies ), which in severe cases leads to the formation of histologically visible subepidermal spaces (English Max Joseph spaces ) and - as in the case of a vesicobuloid lichen planus - clinically visible blisters. In the upper dermis (dermis) there is a ribbon-like inflammatory cell infiltrate , mainly composed of lymphocytes , which can overlap the dermoepidermal border. In between there are numerous melanophages (phagocytes that have absorbed the melanin pigment released from the necrotic keratinocytes ). In addition, there may be erosions or ulcerations (defects in the epidermis).

In the direct immunofluorescence the lichen planus shows a relatively characteristic picture with subepidermal deposits of fibrinogen and marking of rounded necrotic keratinocytes mainly on IgM , but also on IgG , IgA and C3 .

treatment

The aim of therapy is to shorten the duration of the illness, control the itching and minimize complications. The treatment should be appropriate to the severity of the disease and as few side effects as possible.

Cutaneous lichen planus

As first line therapy, cortisone (highly effective glucocorticoids , e.g. triamcinolone ) is recommended as a cream or local injection. If therapy is resistant, systemic glucocorticoid therapy can be tried orally (as a tablet) or as an intramuscular injection . Atrophic lesions should be treated systemically from the start and then as early as possible. Other options are the administration of retinoids or ciclosporin . To relieve the itching, topical anti-itch relievers such as menthol, camphor or doxepin , and if necessary antihistamines in tablet form, can be used.

As second line therapy, topical calcineurin inhibitors ( tacrolimus , pimecrolimus ), sulfasalazine , PUVA photochemotherapy or phototherapy with UV-B rays are suggested, whereby a therapy with UV rays in turn increases the risk of squamous cell carcinoma.

Can be used as third-line therapy should be considered Calcipotriol (topical), metronidazole , trimethoprim , hydroxychloroquine , itraconazole , terbinafine , griseofulvin , tetracycline , doxycycline , mycophenolate mofetil , azathioprine , low molecular weight heparin , photodynamic therapy, treatment with the YAG laser and apremilast .

In the case of genital lichen planus in men, circumcision can be considered, if necessary after an initial attempt at therapy with glucocorticoids.

Patients should be made aware of the increased risk of squamous cell carcinoma, including the typical signs, and regular preventive examinations should be carried out in this regard.

Lichen unguis

The lichen planus of the nails is considered difficult to treat, healing can be achieved in approx. 50% of cases. Therapy should start early in the course of the disease to avoid irreversible damage. Topical glucocorticoids under an occlusive dressing (airtight film dressing) or as a local injection are considered first line therapy , although the latter procedure is painful. Glucocorticoids can be given orally, especially if several nails are involved. Alternatively, tacrolimus (topical), retinoids, chloroquine, ciclosporin, fluorouracil , biotin, and etanercept can be tried.

literature

- D. Ioannides, E. Vakirlis et al .: EDF S1 Guidelines on the management of Lichen Planus. (PDF) In: European Dermatology Forum. Retrieved February 10, 2020 .

- Konrad Bork, Walter Burgdorf, Nikolaus Hoede: Oral mucous membrane and lip diseases: Clinic, diagnostics and therapy. Atlas and manual. Schattauer, 2008, ISBN 978-3-7945-2486-0 , Chapter 22: Lichen ruber planus, pp. 74-83, google.book

- SK. Edwards: European guideline for the management of balanoposthitis . In: Int JSTD AIDS , 2001, 12 (Suppl. 3), pp. 68-72.

- Rajani Katta: Diagnosis and Treatment of Lichen Planus . In: Am Fam Physician. , June 1, 2000, 61 (11), pp. 3319-3324, aafp.org

- G Kirtschig, SH Wakelin, F. Wojnarowska: Mucosal vulval lichen planus: outcome, clinical and laboratory features . In: Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology , 2005, 19 (3), pp. 301-307.

- Laurence Le Cleach, Olivier Chosidow: Clinical practice: Lichen Planus . In: New England Journal of Medicine , 366: 8, February 23, 2012, pp. 723-732.

- G. Wagner, C. Rose, MM Sachse: Clinical variants of lichen planus . In: Journal of the German Dermatological Society , 2013, doi: 10.1111 / ddg.12031

- Alberto Rosenblatt, Homero Gustavo Campos Guidi, Walter Belda: Male Genital Lesions: The Urological Perspective . Springer-Verlag, 2013, ISBN 3-642-29016-7 Google Books pp. 93–95

- Hywel Williams, Michael Bigby, Thomas Diepgen, Andrew Herxheimer, Luigi Naldi, Berthold Rzany: Evidence-Based Dermatology . John Wiley & Sons, Chapter 22: Lichen planus, pp. 189 ff., 744 pages.

- S. Regauer: Vulvar and penile carcinogenesis: transforming HPV high-risk infections and dermatoses (lichen sclerosus and lichen planus) . In: Journal für Urologie und Urogynäkologie , 2012, 19 (2), pp. 22-25

- Libby Edwards, Peter J. Lynch: Genital Dermatology Atlas . Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2010, ISBN 978-1-60831-079-1 , 384 pp.

Web links

- Dr. Angela Unholzer: Lichen planus (lichen planus). In: www.apotheken-umschau.de. Wort & Bild Verlag, October 10, 2018, accessed on March 15, 2020 .

- Lichen planus on the sides of the TK

Individual evidence

- ^ GO Alabi, JB Akinsanya: Lichen planus in tropical Africa . In: Tropical and Geographical Medicine . tape 33 , no. 2 , June 1981, ISSN 0041-3232 , pp. 143-147 , PMID 7281214 .

- ↑ Sanjeev Handa, Bijaylaxmi Sahoo: Childhood lichen planus: a study of 87 cases . In: International Journal of Dermatology . tape 41 , no. 7 , July 2002, ISSN 0011-9059 , p. 423-427 , doi : 10.1046 / j.1365-4362.2002.01522.x , PMID 12121559 .

- ↑ MR Pittelkow, MS Daoud: Lichen planus . In: GK Wolff, L. Goldsmith, S. Katz, B. Gilchrest, A.Paller (Eds.): Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in general medicine . 7th edition. Mc-Graw-Hill, New York 2008, p. 244-255 .

- ↑ a b c d e f D. Ioannides, E. Vakirlis et al .: EDF S1 Guidelines on the management of Lichen Planus. (PDF) In: European Dermatology Forum. Retrieved February 10, 2020 .

- Jump up ↑ Yalda Nahidi, Naser Tayyebi Meibodi, Kiarash Ghazvini, Habibollah Esmaily, Maryam Esmaeelzadeh: Association of classic lichen planus with human herpesvirus-7 infection . In: International Journal of Dermatology . tape 56 , no. 1 , January 2017, p. 49-53 , doi : 10.1111 / ijd.13416 ( wiley.com [accessed February 10, 2020]).

- ↑ B. Tas, S. Altinay: Toluene induced exanthematous lichen planus: report of two cases . In: Global dermatology . ISSN 2056-7863 , doi : 10.15761 / GOD.1000110 .

- ^ JM Mahood: Familial lichen planus. A report of nine cases from four families with a brief review of the literature . In: Archives of Dermatology . tape 119 , no. 4 , April 1983, ISSN 0003-987X , pp. 292-294 , doi : 10.1001 / archderm.119.4.292 , PMID 6838234 .

- ↑ Sanjeev Handa, Bijaylaxmi Sahoo: Childhood lichen planus: a study of 87 cases . In: International Journal of Dermatology . tape 41 , no. 7 , July 2002, ISSN 0011-9059 , p. 423-427 , doi : 10.1046 / j.1365-4362.2002.01522.x , PMID 12121559 .

- ↑ Thomas J. Knackstedt, Lindsey K. Collins, Zhongze Li, Shaofeng Yan, Faramarz H. Samie: Squamous Cell Carcinoma Arising in Hypertrophic Lichen Planus: A Review and Analysis of 38 Cases . In: Dermatologic Surgery: Official Publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.] Volume 41 , no. December 12 , 2015, ISSN 1524-4725 , p. 1411-1418 , doi : 10.1097 / DSS.0000000000000565 , PMID 26551772 .

- ↑ BK Thakur, S. Verma, V. Raphael: Verrucous carcinoma developing in a long standing case of ulcerative lichen planus of sole: a rare case report . In: Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology . tape 29 , no. 2 , February 2015, p. 399-401 , doi : 10.1111 / jdv.12406 ( wiley.com [accessed February 15, 2020]).

- ↑ Eduardo Calonje, Thomas Brenn, Alexander Lazar, Steven D. Billings: McKee's pathology of the skin with clinical correlations . Fifth ed. Without place, ISBN 978-0-7020-7552-0 , p. 242 .

- ↑ Steven Kossard, Stephen Lee: Lichen planoporitis: keratosis lichenoides chronica revisited . In: Journal of Cutaneous Pathology . tape 25 , no. 4 , April 1998, ISSN 0303-6987 , p. 222–227 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1600-0560.1998.tb01723.x ( wiley.com [accessed February 15, 2020]).

- ↑ A. Lallas, A. Kyrgidis, TG Tzellos, Z. Apalla, E. Karakyriou: Accuracy of dermoscopic criteria for the diagnosis of psoriasis, dermatitis, lichen planus and pityriasis rosea . In: The British Journal of Dermatology . tape 166 , no. 6 , June 2012, ISSN 1365-2133 , p. 1198-1205 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1365-2133.2012.10868.x , PMID 22296226 .

- ↑ Strutton, Geoffrey., Rubin, Adam I., Weedon, David .: Weedon's skin pathology . 3rd ed. Churchill Livingstone / Elsevier, [Edinburgh] 2010, ISBN 978-0-7020-3485-5 , pp. 36-45 .

- ↑ Eduardo Calonje, Thomas Brenn, Alexander Lazar, Steven D. Billings: McKee's pathology of the skin with clinical correlations . Fifth ed. [Edinburgh, Scotland?], ISBN 978-0-7020-7552-0 , pp. 250 .

- ^ Edwards, Lynch 2010

- ↑ Laurence Le Cleach, Olivier Chosidow: In: N Engl J Med , 366, February 23, 2012, pp. 723-732

- ↑ Rosenblatt et al., 2013