Reichsland Alsace-Lorraine

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The realm of Alsace-Lorraine was an administrative area of the German Empire formed from parts of the old regions of Alsace and Lorraine from 1871 to 1918. Unlike the federal states, the realm was directly subordinate to the German Kaiser .

history

History up to the founding of the Reichsland

The present-day regions of Alsace and Lorraine have belonged to the East Franconian Empire (later the Holy Roman Empire ) since the Treaty of Meerssen in 870 . As everywhere, there were various imperial city, ecclesiastical and imperial corporate territories.

With the Treaty of Chambord in 1552, the French king gained sovereignty over the diocese and the city of Metz, which finally came to France in the Peace of Westphalia in 1648. Also in the Peace of Westphalia, France became the former Habsburg territories in Alsace, i. H. in particular the Sundgau (excluding the city of Mulhouse, which belonged to the old Swiss Confederation between 1515 and 1798 ) and the Landvogtei through the Alsatian League of Ten Cities.

Most of what was later to become the empire was gradually annexed by France under Louis XIV as part of the reunification policy in the second half of the 17th century. Strasbourg was occupied by the troops of Louis XIV in 1681. For a long time, however, Alsace played a special role in the French kingdom and remained culturally influenced by German. In contrast to the rest of France, there was a tolerance of Protestants , even if the French authorities favored Catholicism wherever possible (the Strasbourg cathedral had to be handed over to the Catholics in 1681), and Alsace was economically separated from the rest by a customs border France separated. In 1766, the Duchy of Lorraine also fell to France in accordance with the provisions of the Peace Treaty of Vienna (1738) .

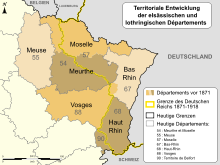

During the French Revolution , after 1789, the old feudal structures and regional special rights and thus many ties to neighboring Germany were eliminated. The region became part of the First French Republic and was divided into newly created departments , the borders of which did not coincide with the old regional borders and the later borders of the empire (see adjacent map). After Napoleon's defeat, Alsace and Lorraine remained with France in the Congress of Vienna in 1815. While the German-speaking inhabitants of the country were still largely connected to German culture before 1789, despite French rule, after the French Revolution more and more Alsatians and Lorraine people oriented themselves towards France and Paris. Since there was no general compulsory schooling in French in France, German was retained as the colloquial and everyday language in Alsace and German-Lorraine .

Alsace-Lorraine in the German Empire

From the Franco-Prussian War to the annexation

The Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71 was unfavorable for France from the start. The first skirmishes in August 1870 near Weißenburg and Wörth in northern Alsace were lost, and the northern German troops and southern German allies occupied Alsace. Strasbourg was besieged by German troops for six weeks. The minster was also damaged by artillery fire, and the old city and university library with its valuable collection of medieval manuscripts was destroyed in a fire, including the only copy of the medieval encyclopedia Hortus Deliciarum by Abbess Herrad von Landsberg . During the siege of Metz , General Friedrich Alexander von Bismarck-Bohlen was appointed Governor General for the German-occupied territories on August 21, 1870 . Shortly afterwards , Friedrich von Kühlwetter took up his work as civil commissioner and thus the head of civil administration at his side. During the war, public opinion in Germany was increasingly oriented towards regaining Alsace, which was still predominantly German in linguistic and cultural terms at that time. In private conversation, Bismarck himself was ambivalent about the annexation. On the one hand, he saw in it the possibility of consolidating the internal unity of the newly founded German Empire; In addition, strategic military considerations spoke in favor of the annexation. On the other hand, as a realpolitician, Bismarck was aware that this would put a permanent strain on the Franco-German relationship. But he also assumed a Franco-German enmity with or without annexation as a historical constant. In the years after the war he feared a cauchemar des coalitions , a “coalition nightmare”. He tried to counter France, which was looking for revenge, through an extensive defensive alliance system.

With the Peace of Frankfurt in May 1871, Alsace and the northern part of Lorraine were annexed to the newly founded German Empire . The international law transfer of territory took place on March 2, 1871, the day the Versailles preliminary peace came into force ; Alsace-Lorraine became an integral part of the Reich territory in the constitutional sense on June 28, 1871 with the entry into force of the Reich Law of June 9, 1871 on the unification of Alsace and Lorraine with the German Empire . In September 1871 the military government was dissolved and the administration was transferred to the high presidium under Eduard von Moeller .

The demarcation in the Alsace area essentially followed the language border along the main ridge of the Vosges . However, for strategic military reasons, an area with a French-speaking population was included around the places Schirmeck east of the Vosges ridge and Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines . Belfort, which was historically part of southern Alsace (that is to say the Sundgau ), but has been French-speaking since time immemorial, with its surrounding area ( Arrondissement Belfort ) at the Burgundian Gate remained with France.

Most of the old total of Lorraine (Lorraine) with the capital Nancy remained with France, but the city of Metz, including the fortress and surrounding area, was added to the German Empire - mainly for strategic reasons. As a result of this demarcation, 200,000 Lorraine people with French as their mother tongue became Imperial Germans . It is true that it was only about 15% of the population of Alsace-Lorraine, thus significantly less than the German-speaking Alsatians and Lorraine in France, who were both before and afterwards; however, this circumstance put an additional strain on Franco-German relations in the following decades.

The option

The residents of Alsace-Lorraine, provided they had not immigrated from central France, received Alsace-Lorraine citizenship according to the provisions of the Peace Treaty of Frankfurt, but had the option of retaining French citizenship until October 1, 1872 . The original plan was that those who opted for French citizenship (so-called optanten ) would have to leave the country. They were allowed to take their property with them or to sell them freely. A total of 160,878 people opted, i.e. H. about 10.4% of the total population, for French citizenship. The proportion of optants was particularly high in Upper Alsace, where 93,109 people (20.3%) said they wanted to keep French citizenship, and significantly lower in Lower Alsace (6.5%) and Lorraine (5.8%).

Ultimately, however, only a fraction of the optants actually emigrated to France. A total of about 50,000 people left the Reich for France, which corresponded to 3.2% of the population. The 110,000 or so optants who had not emigrated by October 1, 1872 had lost their option of French citizenship. However, they were not expelled by the German authorities either, but retained their German citizenship. Even after 1872 people emigrated permanently, without the reasons being clearly stated. Germany as a whole was a distinct emigration country until the 1890s. In some cases, however, young Alsatians wanted to avoid military service in the German army in this way . Through the optants, many Alsace-Lorraine residents had family ties to France, as it was not uncommon for some family members to opt for France and emigrate there, while others stayed in the country.

Acceptance of the annexation on the part of the local population

While the proportion of German-speakers was around 90%, but to Catholic parts of Alsace-Lorraine population behaved towards the under the leadership of Protestant dominated Prussia concluded had come ethnographic reunion with Germany rather skeptical. While the Catholics often identified with the French Catholic state and feared being disadvantaged by the predominantly Protestant Prussia, the local Protestants were in favor of belonging to the German Empire. The Evangelical Lutheran Church committed itself to Germany and hoped that this would push back the French-influenced Catholic paternalism. The rural population in particular supported the efforts, while a number of critics of the reunification spoke up in the cities of Strasbourg and Mulhouse.

While this was to be expected among the French-speaking minority, German administrative officials who came to the country reacted with consternation to the observation that many Alsatians, most of whom could not even speak French, were Francophiles . The Prussian Ministerialrat Ludwig Adolf Wiese wrote about a visit to Alsace-Lorraine in May / June 1871:

“The overall impression [...] was more depressing than hopeful. The estrangement of the Lorraine and Alsatians from Germany went much deeper, and their attachment to France was more intimate than I had expected; they no longer had any national contact with us. It did not matter to the Alsatians that in France they were actually only considered a low and imperfect species of French, and were often used for comic figures; Nevertheless, it was an honor to belong to them, to the grande nation . [...] it was puzzling and saddening to me how the dazzling of the French name, the captivating character of the French forms of education, and finally the great power of habit had also captured nobler and more educated minds [...] ... "

Most of the 15 Alsatian-Lorraine MPs elected in the Reichstag elections from 1874 to 1887 were assigned to the "Protestor MPs" (French députés protestataires ) because of their opposition to the annexation . Shortly after the first Reichstag election in Alsace-Lorraine in 1874 , the protesters in the Reichstag proposed that a plebiscite should be held about the state belonging to the Reichsland: “The Reichstag should decide that the population of Alsace-Lorraine, without having been questioned , which has been incorporated into the German Reich by the Treaty of Frankfurt, is called upon to comment on this annexation. ”The motion was rejected by a large majority. Neither in 1870/71 nor in 1918 was the population asked for their opinion on state affiliation, any more than it had been in times before that, around 1681 and 1814/15.

The protesters refused to cooperate with the German authorities and to do constructive political work in the Reichstag and after their election did not take part in its meetings (some elected Lorraine MPs were unable to do so due to a lack of command of the German language). In addition, however, there were also people in political life who, for various reasons, pleaded for an “attitude of reason”. These so-called autonomists were more or less friendly to Germany or France and strove for a local, as extensive as possible autonomy of the Reichsland.

The denomination played an important role in the attitude of the population towards annexation. After the conflict between the state and the Catholic Church, the so-called " Kulturkampf ", also broke out in Alsace-Lorraine from 1872/73, the Catholic Church became a vehicle for resistance against the German authorities. During all elections to the Reichstag between 1874 and 1912, of the 15 Alsace-Lorraine MPs, between three and seven were Catholic priests . This dispute reached a climax when, on August 3, 1873, a pastoral letter from the Bishop of Nancy-Toul was read in the districts of Château-Salins and Saarburg , which (still) belonged to his diocese, in which a prayer for reunification was read Alsace-Lorraine with France was called. The German authorities reacted with police measures , arrests and disciplinary proceedings, as well as a ban on Catholic press organs. From the Reichstag election in 1877, the majority of the evangelical minority population voted for the autonomists. Over time, however, the Alsace-Lorraine people turned more and more to the Reich German parties, such as the Catholics to the center, the Protestant bourgeoisie to the liberals and conservatives and the emerging workers of the SPD. The protesters no longer played an essential role after the 1890 election.

From the beginning of the 20th century, the opposition to the Reich German authorities played an increasingly minor role. The secular politics of France from 1905 ( law separating church and state ) led to an alienation from France in Catholic circles. In addition, the German Reich had granted the region significantly more freedom and the region's economic situation had developed very positively. Younger residents in particular, who had no contact with France, saw themselves as Germans as a matter of course.

Results of the Reichstag elections 1874–1912

The residents were given the right to vote in the German Reichstag, in which the Reichsland was represented from 1874 with 15 members (of 397). The following table shows the results of the Reichstag elections in Alsace-Lorraine from 1874 to 1912.

| 1874 | 1877 | 1878 | 1881 | 1884 | 1887 | 1890 | 1893 | 1898 | 1903 | 1907 | 1912 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population (in thousands) | 1550 | 1532 | 1567 | 1564 | 1604 | 1641 | 1719 | 1815 | 1874 | |||

| Eligible voters (in%) | 20.6 | 21.6 | 21.0 | 19.9 | 19.5 | 20.1 | 20.3 | 20.3 | 21.0 | 21.7 | 21.9 | 22.3 |

| Voter turnout (in%) | 76.5 | 64.2 | 64.1 | 54.2 | 54.7 | 83.3 | 60.4 | 76.4 | 67.8 | 77.3 | 87.3 | 84.9 |

| Conservative (K) | 2.2 | 0.3 | 12.1 | 3.2 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 12.0 | 6.2 | 0.3 | |||

| German Reich Party (RP) | 7.7 | 14.6 | 9.1 | 7.8 | 2.8 | 2.1 | ||||||

| National Liberals (NL) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 11.5 | 8.5 | 4.7 | 6.0 | ||||

| Alsatian Progressive Party (EFP) | 17.2 | 19.5 | ||||||||||

| Liberal Association (FVg) | 8.2 | 6.2 | ||||||||||

| Liberal People's Party (FVp) | 1.9 | 0.5 | ||||||||||

|

Alsace-Lorraine / People's Democratic Party |

0.9 | 3.2 | ||||||||||

|

Alsace-Lorraine Center (ELZ) |

7.8 | 24.3 | 25.9 | 35.2 | 28.5 | |||||||

| Center Party (Z) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 7.1 | 4.4 | 5.4 |

| SPD Alsace-Lorraine (S) | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 1.8 | 0.3 | 10.7 | 19.3 | 22.7 | 24.2 | 23.7 | 31.8 | |

| Protester (P) | 32.2 | 35.7 | 31.9 | 54.1 | 55.6 | 59.5 | 10.4 | 2.7 | 0.0 | 4.5 | ||

| Autonomists (AU) | 19.0 | 26.3 | 23.7 | 11.3 | 8.5 | 15.4 | 0.7 | 2.1 | 2.1 | |||

| Individual candidates of political Catholicism (KT) |

44.0 | 37.3 | 32.0 | 28.3 | 31.9 | 22.7 | 46.0 | 35.3 | 14.5 | 2.9 | 2.5 | |

| Lothringer Block Independent Lorraine. Party (LO) |

11.2 | 15.9 | 14.1 | 7.1 | ||||||||

| Others | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 1.9 | 12.0 | 7.0 | 5.9 | 0.2 |

| 1874 | 1877 | 1878 | 1881 | 1884 | 1887 | 1890 | 1893 | 1898 | 1903 | 1907 | 1912 | |

| Mandate distribution | P 6 KT 9 |

P 5 AU 5 KT 5 |

P 5 AU 4 KT 6 |

P 8 AU 1 KT 6 |

P 9 AU 1 KT 5 |

P 10 KT 5 |

P 1 KT 9 K 1 RP 1 NL 2 S 1 |

P 1 KT 7 K 3 RP 1 S 2 FVg 1 |

KT 8 LO 2 K 2 RP 1 S 1 FVg 1 |

KT 7 LO 4 RP 1 NL 1 FVg 1 Fp 1 |

ELZ 8 KT 1 LO 3 RP 1 S 2 |

ELZ 7 S 5 LO 2 EFP 1 |

- FVp: Progressive People's Party , created through the amalgamation of all left-liberal groups.

- ELZ: Alsace-Lorraine Center Party , founded in 1906, predecessor organizations were the regional association of the German Center Party and the local groups of the People's Association for Catholic Germany

The compilation shows that the vast majority of the residents of the Reichsland were skeptical of the German Reich in the first two decades and voted for regional parties (Alsace-Lorraine protesters and autonomists). After Bismarck's dismissal in 1890, however, the party landscape loosened up, and Reich German parties ( SPD , Center , National Liberals, Left Liberals, Conservatives) found more and more supporters. In the countryside and in the predominantly French-speaking constituencies of Lorraine, the autonomists remained strong; in the cities, especially in Strasbourg, they played an increasingly subordinate role, where the social democrats dominated. However, the majority suffrage in force in the German Reichstag favored regional parties and disadvantaged large mass parties such as the SPD.

Military-political development in Alsace-Lorraine

In the decades after 1871, under German rule , the fortress of Metz was expanded to become the largest fortress in the world with a ring of porches, some of which were located far in front of the actual fortifications. Due to the influx of military personnel and other old Germans , i.e. immigrants from the rest of Germany, Metz became a predominantly German-speaking city.

When the German Army was formed after the founding of the empire, the XV. Prussian army corps emerged. The corps received its district in the new border region of Alsace-Lorraine, just like the XVI. Army Corps. The southern territories of the Empire State were among the districts of 1871 from Baden troops prepared XIV. , And in 1912 the northeastern for XXI. Army Corps .

The recruiting areas of these corps were outside Alsace-Lorraine. This also applied to the Upper and Lower Alsatian and Lorraine regiments that were later set up with these corps as part of army enlargements and were not always stationed in the Reichsland . The Alsatians and Lorrainers drafted for military service, on the other hand, were distributed individually to all Prussian army units , as were active and passive Social Democrats , who were just as politically unreliable . It was not until 1903 that a quarter of Alsatian recruits were drafted into the troops stationed in their home country on a trial basis.

In 1910, 4.3% of the local population - around 80,000 people - were members of the military, making Alsace-Lorraine the most densely populated region in Germany and at the same time the highest male population (in 1900: 880,437 male and 839,033 female residents) .

Status as 'Reichsland'

While it was part of the empire, there was a strong economic boom and lively construction activity. The often monumental buildings often served representative purposes and were also intended to architecturally demonstrate that the Reichsland belonged to Germany. Today they are often significant examples of Wilhelmine architecture .

Since the German Reich was a federal state made up of member states , but initially they did not want to grant the new gain any independence, various options for integration were discussed:

- Incorporation as a Prussian province

- Incorporation of Lorraine into the Kingdom of Bavaria (merging with the Palatinate district ) and incorporation of Alsace into the Grand Duchy of Baden .

- New creation of a "Reichsland", which is assigned to the Reich (not a specific individual state of the Reich) and which is administered directly by the Emperor.

In particular, the so-called 'Prussian solution' was initially very vividly advocated from various sides. The historian Heinrich von Treitschke advocated this solution in the German Reichstag in 1871 with the following justification:

- “The task of reintegrating these estranged tribes of the German nation into our country is so big and difficult that it can only be entrusted to tried and tested hands, and where is a political force in the German Empire that has tried the gift of Germanizing, how? the old glorious Prussia. "

Otto von Bismarck campaigned in the Reichstag for the solution that Alsace-Lorraine would pass to the Reich itself, not least because he had to take into account the interests of the southern German states. In view of the imminent Kulturkampf against Catholicism, the high proportion of Catholics among the new citizens also caused concern.

The possibility of granting Alsace-Lorraine the status of a member state of the German Empire with its own sovereign and its own constitution was not considered; not least because Prussia was convinced that the population of the country would have to be “Germanized” first, that is, had to get used to the new German-Prussian form of government. That is why the Reichsland was initially treated like an occupied territory and administered directly by a Reich Governor appointed directly by the Emperor. There was only participation of the population in political power at the local level and in the elections to the Reichstag.

In 1874 the Bismarckian constitution was introduced. An advisory state committee was set up. In 1879 the office of Imperial Lieutenant was introduced in Alsace-Lorraine , who represented the realm of Alsace-Lorraine as head of the region. The State Secretary of the Reich Office for Alsace-Lorraine headed the government of the Reich. In the German Empire from 1877 the country received the right to propose laws. In 1911 Alsace-Lorraine was largely assimilated to the federal states (see below), and a first state parliament was elected.

Upper Presidents and Imperial Lieutenants 1871–1918:

| Upper President of the realm of Alsace-Lorraine | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Surname | Beginning of the term of office | Term expires |

| 1 | Eduard von Moeller | 1871 | 1879 |

| Imperial governor in Alsace-Lorraine | |||

| 1 | Edwin von Manteuffel | 1879 | 1885 |

| 2 | Clovis of Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst | 1885 | 1894 |

| 3 | Hermann zu Hohenlohe-Langenburg | 1894 | 1907 |

| 4th | Karl von Wedel | 1907 | 1914 |

| 5 | Johann von Dallwitz | 1914 | 1918 |

| 6th | Rudolf Schwander | 1918 | 1918 |

Economic and cultural development

As early as 1871 there were plans for a strategic railway line from Berlin via Wetzlar and Koblenz to Metz, in order to also integrate the new Reichsland strategically. This " cannon train " was then realized in the 1870s. The local railways of the private French Ostbahn-Gesellschaft ( Compagnie des Chemins de Fer de l'Est ) - a total of 740 km of routes - were initially bought by the French state and then sold to the German Empire for 260 million gold marks. The purchase price was set off against the compensation for war costs to be paid by France. From this, the Reichseisenbahnen in Alsace-Lorraine was formed, the first railway owned by the German Empire. Since 1883 there were plans for the Moselle canalization in order to connect the industry in Lorraine with the Rhine . Up to the First World War the country experienced a great economic boom, many new socio-political achievements such as social security and health insurance were introduced in line with developments in the rest of the German Empire.

In 1872 the University of Strasbourg was re-established and in 1877 was named "Kaiser Wilhelm University" (after Wilhelm I ). Generous expansion plans made it one of the largest universities in the empire.

Despite these positive developments, the relationship between the Alsace-Lorraine and German authorities remained ambivalent and not free of tension until the end of the Empire in 1918. The Prussian military and administrative officials, who often appeared insensitive and perceived as foreigners, also contributed to this, as the events surrounding the Zabern affair in 1913 showed.

Development towards a federal state of the empire

It was not until 1911 that Alsace-Lorraine was largely equated with the German federal states and with the law on the Alsace-Lorraine constitution of May 31, 1911, it received its own constitution , its own freely elected parliament and three representatives in the German Federal Council. The governor had to determine how they would vote, whereby the votes could not be counted if they would give a majority to an otherwise unsuccessful application by Prussia . With the attempt to introduce its own, red and white state flag, the state parliament could not prevail against the Berlin government in 1912.

The state parliament consisted of two chambers. The first chamber consisted of representatives of the major religious communities (Catholics, Lutherans, Reformed, Jews), the chambers of agriculture and commerce, the trade unions, the judiciary, the cities of Strasbourg, Metz, Mulhouse and Colmar, the University of Strasbourg and some appointed by the emperor Members together. The members of the second chamber were elected according to the general equal suffrage (for men over 25 years) in 60 individual constituencies.

For the time, the constitution was both conservative because of the first chamber and progressive because of universal equal male suffrage. The involvement of trade union representatives was also remarkable, as they were not yet legally recognized as employee representatives at the time. The first and only elections to the Landtag of the Reichsland took place on October 22, 1911. The strongest parties were the Alsatian center and the Social Democrats with 31.0% and 23.8% of the vote, respectively, followed by the Autonomists with 16.3%.

Brief independence as the Republic of Alsace-Lorraine at the end of 1918

At the Kiel Mutiny and Alsatians were involved. They hadn't wanted to use them on the Western Front and had therefore been drafted into the Navy. On November 9th the republic was proclaimed in Berlin ( November Revolution), on November 10th 1918 the emperor fled his headquarters in Spa, Belgium, to the Netherlands , on November 11th the Compiègne armistice came into force. provided that Alsace-Lorraine should be evacuated within 15 days. Wilhelm did not officially abdicate until November 28, 1918, but the Reichsland Alsace-Lorraine was de facto granted independence after the head of state had fled . The state parliament under Eugen Ricklin proclaimed the independent republic of Alsace-Lorraine on November 11, 1918, which was not recognized internationally because the war aims of the Allies envisaged the annexation of Alsace-Lorraine to France.

After about a week, French troops moved in: on November 17th in Mulhouse , then in Colmar and Metz, and on November 21st they reached Strasbourg. This ended independence. Initially, some sections of the population, especially the Catholic, reacted enthusiastically to the annexation to France. This subsided when the French began to enforce their policies of assimilation .

Part of France

The Reichsland or the Republic of Alsace-Lorraine was dissolved on October 17, 1919 and from then on administered by a general management in Paris .

Evictions

From December 14, 1919, the inhabitants of Alsace were divided into four groups, depending on their origin:

- A Entirely French: residents who were born in France or Alsace-Lorraine before 1870 or whose parents / grandparents were born

- B Partly French: one of the parents or grandparents came from France or Alsace-Lorraine before 1870

- C Foreigners: residents who themselves or their parents / grandparents came from a country that was allied with France or was neutral

- D Germans: residents who themselves or their parents / grandparents came from the rest of the German Empire or from Austria-Hungary.

Class D persons, immigrants of German descent after 1870 and their descendants, were expelled . Around 100,000 people from Lorraine and around 150,000 people from Alsace had to leave the former Reichsland for Germany between December 1918 and October 1920. Each adult was allowed to take 30 kg of luggage with them and per adult was allowed to take cash with them for 2,000 marks and for children to take 500 marks. The remaining properties were confiscated by the French state.

A plebiscite there were similar to the year 1871/72 is not, as you officially forward the slogan: "Pas de plebiscite! On ne choisit pas sa mère ” (“ No referendum! You don't vote for your mother ”). In addition, a vote appeared superfluous, since the cheers at the greeting of the French troops were interpreted as evidence of the deep desire of the Lorraine and Alsatians to become French again. On December 5, 1918, the French National Assembly finally passed the "inviolable right of Alsace-Lorraine to remain members of the French family". In a speech in Metz on December 8, 1918, French President Raymond Poincaré made it clear that a plebiscite was not to take place by declaring: “Your reception proves to all the Allied nations how right France was when it asserted that it was The heart of Lorraine and Alsace has not changed. "

After US President Woodrow Wilson put pressure on the government in Paris, around half of the expelled Germans were able to return to the territory of the former Reich of Alsace-Lorraine in the following months.

At the University of Frankfurt am Main , the Scientific Institute of the Alsace-Lorraine in the Reich was founded in 1921, which researched the history of Alsace and Lorraine up to the end of the First World War.

aftermath

Due to the French policy of assimilation, discontent grew within the Alsatian population. This encouraged a strong autonomist movement. In the elections to the French Chamber of Deputies , the Alsatian Autonomists, who cooperated with the Communist Party and the Breton and Corsican nationalists, won an absolute majority of the votes in all Alsatian constituencies. The MPs and politicians who spoke out in favor of autonomy were often sentenced to long prison terms by the French state, and the leader of the Autonomist Party, Karl Roos , was executed in Nancy on February 7, 1940 for alleged espionage.

Second World War - German occupation

From June 19, 1940, the Wehrmacht occupied Alsace.

Under the National Socialists , Alsace-Lorraine was not officially incorporated, but was nevertheless incorporated into the Greater German Reich as a CdZ area (including the CdZ area of Lorraine ); “Despite a 'de facto annexation' of the former Reichsland”, it remained “non-German national territory under constitutional law” throughout. After the victory over France there was hope for a peace in the west, which would have been made even more difficult by a formal annexation of Alsace-Lorraine.

Pretty soon after the Wehrmacht marched in, there were resettlements and expulsions in Lorraine. French people who had no German roots were affected. From the German side, repatriates were supposed to occupy the vacant farm positions. Almost half of the population of the Moselle department was affected by these evictions . At the Pompidou Center in Metz , a plaque commemorates these events. The Moselle department was incorporated into the Reichsgau Westmark together with the Saarland and the Palatinate (Bavaria) .

In 1941 the University of Strasbourg was founded.

From 1942 onwards, the Alsatians and Lorraine people also had general conscription. Many of them had to do their military service reluctantly ( malgré-nous ) in the Wehrmacht or in the Waffen SS ; however, there were also volunteers among them. Fourteen Alsatians (including one volunteer) were involved in the Oradour massacre .

Post-war France

After the Second World War , the French government pursued a linguistic assimilation policy (“c'est chic de parler français”). As a result, Alsatian, and especially Lorraine , lost such importance as a mother tongue that the majority of those born after around 1970 can no longer speak it today.

Since 1972 there have been regional parliaments again in Alsace and Lorraine. Autonomist parties, such as Alsace d'abord , currently receive less than 10% of the vote.

The changes in the borders of the departments of Meurthe (then Meurthe-et-Moselle ), Moselle and Vosges, caused by the assignment of Alsace-Lorraine in 1871 , as well as the separation of the Territoire de Belfort from the Haut-Rhin department , were retained by France after 1918. The former departments of Haut-Rhin, Bas-Rhin and Moselle are congruent with the districts of Upper Rhine, Lower Rhine and Lorraine created in the Reichsland. The administrative structure at the municipal level introduced after 1871 was not reversed in France, so that the current arrondissements correspond to the districts formed after 1871 (if one disregards more recent amalgamations such as the Arrondissement Sélestat-Erstein ).

The area of the former Reichsland (Alsace-Moselle) has preserved some special features from before 1918 within France. These include additional public holidays (Good Friday, Boxing Day), some peculiarities in the legal system and the non-application of the French secularity law of 1905 to existing religious communities: as a result of the Concordat of 1801, priests, pastors and rabbis are state salary earners, religious instruction is given at school, there are State theological faculties at the University of Strasbourg and state-funded denominational schools . However, these privileges do not apply to religious communities that emerged after 1918, such as Muslims and Orthodox Christians. Rail traffic is still on the right (left-hand traffic in the rest of France).

In Alsace and in the Moselle department, various legal provisions from the period from 1871 to 1918 continue to apply, including the trade regulations (Code local des professions) and social security law (in particular the Reich Insurance Code ). As a result, z. B. the rate of the statutory minimum wage ( Salaire minimum interprofessionnel de croissance, SMIC) in these three departments (2014: 7.87 euros / h) from that in the rest of France (2014: 8.03 euros / h).

Administrative division

The Reichsland was divided into three districts:

- District of Upper Alsace, corresponds to today's department of Haut-Rhin with the main town of Colmar

- District of Lower Alsace, corresponds to today's Bas-Rhin department with the capital Strasbourg

- Lorraine district, corresponds to today's Moselle department with the main town of Metz

The following districts and counties existed in the Reichsland:

District of Upper Alsace

District of Lower Alsace

- Circles

- Strasbourg urban district

- Strasbourg county

- District of Erstein

- Hagenau district

- Molsheim district

- District of Schlettstadt

- Weissenburg District

- Zabern district

Lorraine district

- Circles

- City of Metz

- Metz district

- Bolchen district

- Château-Salins county

- District of Diedenhofen , until 1901, then divided into

- Forbach district

- Saarburg district

- Saargemünd district

For the dishes see the list of dishes in the realm of Alsace-Lorraine .

population

languages

In the Reichsland, 11.6% of the population spoke French as their mother tongue in 1900, 11.0% in 1905 and 10.9% in 1910 . The new German administration was tolerant of the French language. This stood in contrast to the German eastern provinces, in which a policy of cultural Germanization was increasingly being pursued against the Polish minority or, locally, majority population. In 1905, 3,654 of the 167,678 residents of Strasbourg gave French as their mother tongue.

Most of the French-speaking population lived in the Lorraine district. In 1910, 22.3% of the population there spoke French as their mother tongue. The only district with a majority French-speaking population in 1910 was Château-Salins (68.4%). In the districts of Upper Alsace (1910: 6.1%) and Lower Alsace (1910: 3.8%), the French-speaking population made up only a small minority. However, there were also Alsatian cantons in the Vosges with a predominantly French-speaking population. In some cases, because of political opposition, Alsatians gave French as their mother tongue in the census, although this was not the case. In general, there was a tendency for French to decline.

The language issue was regulated in a law of March 1872: German became the official business language in principle, but in the parts of the country with a predominantly French-speaking population, a French translation should be attached to public notices and enactments. Another law of 1873 allowed the district administrations of Lorraine and the district administrations of those districts in which French was wholly or partly the vernacular to use French as the language of business. This affected 420 parishes in 1871 and 311 parishes in 1905. In a law on education of 1873 it was regulated that in the areas with German as the vernacular it was also the exclusive school language, while in the areas with a predominantly French-speaking population, lessons were held exclusively in French. At this time compulsory schooling was also introduced (in France not until 1882).

The French place names in French-speaking areas have been left as they are. Some place names were Germanized in 1871 because it was believed that they could be traced back to an older Germanic form of the name. When this proved to be historically untenable, the renaming was reversed (one example was Château-Salins , which was temporarily renamed Salzburg ). In 1872 a complete geographic-topographical-statistical local lexicon of Alsace-Lorraine , based on official sources, was published in Leipzig , which included the cities, towns, villages, castles, communities, hamlets, mines and steelworks, farms, mills, ruins, mineral springs, etc. contained. It was not until 1915, during the First World War, that the French place names were systematically “Germanized”.

Religions

Regarding denomination, the Reichsland was predominantly Catholic (1900: 76.2%) and had the highest proportion of Catholics of all the countries of the Kaiserreich. However, there were also historically significant centers of the Reformation and the Protestant denomination (Lutheran: Strasbourg, Reformed: Mulhouse - although the majority of the population of both cities was Catholic at the end of the 19th century). The only predominantly Protestant group was Zabern in Lower Alsace. In Lower Alsace the Protestant population made up about 35.5%, the state capital Strasbourg became mixed denominational through immigration from the rest of the Reich (1910: 44.5% Protestant). In Upper Alsace (14.3% Protestant in 1910) the Protestants were concentrated in the canton of Münster ( Colmar district ), where they formed a narrow majority. In Lorraine, which is traditionally Catholic, the proportion of Protestants in the population increased, primarily due to old German immigration (1910 13.0% Protestants).

| mother tongue | number | in percent |

|---|---|---|

| German | 1,492,347 | 86.8% |

| German and another language | 7,485 | 0.4% |

| French | 198,318 | 11.5% |

| Italian | 18,750 | 1.1% |

| Polish | 1,410 | 0.1% |

| Religions | ||

| Catholics | 1,310,450 | 76.21% |

| Protestants | 372.078 | 21.64% |

| Other Christs | 4,416 | 0.26% |

| Jews | 32,264 | 1.88% |

The " Kulturkampf " in the years after the founding of the empire led to an additional alienation of the Catholic majority population from the new authorities; often the pro-French or autonomist endeavors were particularly supported by Catholic clergy ( e.g. Emile Wetterlé ). However, the relationship between the Catholic Church and the German authorities improved after the conflict between the Catholic Church and the French Republic (1905 law separating church and state with the introduction of secularism) became virulent in 1905 . In the long term, however, the ties to France in the Catholic regions were much stronger, so that the French troops were received there with enthusiasm at the end of 1918, while in Protestant regions people were more cautious due to the stronger ties to Germany. The Reichsland also had a higher than the Reich average share of the Jewish population who had lived there since time immemorial (1900: 1.9% compared to about 0.9% in the whole of the Empire and about 0.1% in neighboring France) . While the Jews were completely expelled from central France in the Middle Ages , they were spared this fate in the eastern provinces that were later annexed to France.

Immigration

In particular in the years 1875 to 1885 there was a considerable immigration of people from the rest of the German Empire (mostly from southern Germany, so-called "old Germans"). According to the 1910 census, these immigrants made up 15.8% of the population. The immigrants were distributed very differently. In particular, the industrial districts of Lorraine were affected by immigration. Of the inhabitants of the district capital Metz, which was almost entirely French-speaking before 1871, in 1910 13,731 people stated that they were French as their mother tongue (25%), 40.051 stated that they were German (73%) and 300 people stated that they grew up bilingually (0 , 54%).

In Alsace, only the cities of Strasbourg and Weissenburg had a higher proportion of old Germans (1910: 19.2% and 41.6% respectively). The immigrated old Germans integrated themselves into the long-established population, which can be deduced from the number of mixed marriages between immigrants and locals.

The Lorraine district had by far the highest proportion of foreigners in the German Reich (1905 in the Diedenhofen-West district: 30.5%). Almost two thirds were Italian guest workers who had been lured into the Lorraine steel district by the high wages.

coat of arms

The coat of arms approved by the imperial decree of December 29, 1891 shows the German imperial eagle (without chain of the order) with the imperial crown hovering over it, topped with a split shield crowned with the ducal crown. The heraldic right, diagonally divided half shows above in the red field an inward-facing golden sloping beam accompanied by three golden crowns (2: 1) each (for the Landgraviate of Upper Alsace), below in the red field a silver one also turned to the left, alternately decorated with pearls of the same color and three-leaves on both sides Inclined beam (for the Landgraviate of Lower Alsace). In the golden field of the left half of the shield, a red sloping bar with three mutilated white eagles placed at an angle appears (for the Duchy of Lorraine).

Since the construction of the Reichstag building in 1894, the coat of arms of the realm of Alsace-Lorraine has been on the west facade as a relief next to those of the federal states of the German Empire.

Literature and sources with statistical information

- Complete geographical-topographical-statistical local lexicon of Alsace-Lorraine. Contains: the cities, towns, villages, castles, municipalities, hamlets, mines and smelting works, farms, mills, ruins, mineral springs, etc. with details of the geographical location, factory, industrial and other commercial activities, the post, railroad and telegraph stations and historical notes etc. Adapted from official sources by H. Rudolph. Louis Zander, Leipzig 1872 ( e-copy ).

- Georg Lang: The government district of Lorraine. Statistical-topographical manual, administrative schematic and address book , Metz 1874 ( e-copy )

- Eugen H. Th. Huhn: German-Lorraine. Regional, folk and local studies , Stuttgart 1875 ( e-copy ).

- Alsace-Lorraine , in: Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon . 6th edition, Volume 5, Leipzig / Vienna 1906, pp. 725–736 ( Zeno.org )

literature

Modern treatises

- Ansbert Baumann: The invention of the border region Alsace-Lorraine . In: Burkhard Olschowsky (Ed.): Divided regions - divided cultures of history? Patterns of identity formation in a European comparison (= writings of the Federal Institute for Culture and History of Germans in Eastern Europe, Vol. 47; Writings of the European Network Remembrance and Solidarity, Vol. 6). Oldenbourg, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-486-71210-0 , pp. 163-183.

- Ernst Bruck: The constitutional and administrative law of Alsace-Lorraine . 3 volumes. Trübner, Strasbourg 1908–1910.

- Markus Evers: Disappointed hopes and immense distrust. “Old German” perceptions of the “Reichsland Alsace-Lorraine” in the First World War (= Oldenburg writings on historical science , vol. 17). BIS-Verlag, Oldenburg 2016, ISBN 978-3-8142-2343-8 . ( Digitized version )

- Stefan Fisch : Alsace in the German Empire (1870 / 71-1918). In: Michael Erbe (Ed.): The Alsace. Historical landscape through the ages . Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-17-015771-X , pp. 123-146.

- Thomas Höpel : The Franco-German border area: border area and nation building in the 19th and 20th centuries. In: Institute for European History (Mainz) (Ed.): European History Online , 2012.

- Daniel-Erasmus Khan : The German state borders. Legal historical foundations and open legal questions (= Jus Publicum , Bd. 114). Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2004, ISBN 3-16-148403-7 , pp. 66-70.

- Lothar Kettenacker: National Socialist Volkstumsppolitik in Alsace . Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1973, ISBN 3-421-01621-6 (also Univ., Philos. Fac., Diss. Frankfurt (Main), 1968).

- Sophie Charlotte Preibusch: Constitutional developments in the realm of Alsace-Lorraine 1871-1918. Integration through constitutional law? Berliner Wissenschaftsverlag, Berlin 2010, ISBN 3-8305-1112-4 (= Berlin Legal University Writings - Fundamentals of Law , Volume 18) ( limited preview ).

- Max Rehm: Reichsland Alsace-Lorraine: Government and Administration 1871 to 1918. Pfaehler-Verlag, Bad Neustadt 1991, ISBN 3-922923-77-1 .

- François Roth: La Lorraine annexée, Études sur la Présidence de Lorraine dans l´Empire allemand (1871–1918), 2nd edition, Metz 2007.

- Eugen Rümelin : The constitutional concept of constitutional representation of the people and its applicability to the Alsace-Lorraine regional committee. Dissertation Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg , 1904.

- Hans-Ulrich Wehler : Alsace-Lorraine from 1870 to 1918. The "Reichsland" as a political and constitutional problem of the second German empire . In: Commission for historical regional studies in Baden-Württemberg (ed.): Journal for the history of the Upper Rhine , Vol. 109 / NF 70, Karlsruhe 1961, pp. 133–199.

- Niels Wilcken: Architecture in the border area. Public construction in Alsace-Lorraine (1871-1918) (= publications by the Institute for Regional Studies in Saarland , vol. 38). Inst. For regional studies in Saarland, Saarbrücken 2000, ISBN 3-923877-38-2 .

Contemporary treatises, descriptions and reports

- August Schricker: Alsace-Lorraine in the Reichstag from the beginning of the first legislative period to the introduction of the imperial constitution . Edited and published according to the stenographic minutes and printed matter of the Reichstag. Karl J. Trübner, Strasbourg 1873 ( e-copy ).

- Statistical Bureau of the Imperial Higher Presidium of Strasbourg: Statistical description of Alsace-Lorraine . Volume I, CF Schmidt's Universitäts-Buchhandlung Friedrich Bull, Strasbourg 1878 ( e-copy ).

- Official news for Alsace-Lorraine. Ordinances and notices of the Governor General, the Civil Commissar and the Upper President - August 1870 to the end of March 1879. (Reprinted from the “Official News” of the Strasbourg newspaper.) Karl J. Trübner, Strasbourg 1879 ( e-copy ) .

- Maximilian du Prel: The German administration in Alsace-Lorraine 1870-1879. Memorandum edited using official sources . Karl J. Trübner, Strasbourg 1879 ( e-copy ).

- F. Althoff, Richard Förtsch , A. Harseim, A. Keller and A. Leoni: Collection of the laws in force in Alsace-Lorraine . Volume 1: Constitutional law and statutes , Karl J. Trübner, Strasbourg 1880 ( e-copy ).

- Dietrich Günther von Berg: Communications on the forestry conditions in Alsace-Lorraine . R. Schultz & Cie., Strasbourg 1883 ( e-copy ).

- Statistical office of the Imperial Ministry for Alsace-Lorraine: Local directory of Alsace-Lorraine. Compiled on the basis of the results of the census of December 1, 1880 . CF Schmidts Universitäts-Buchhandlung Friedrich Bull, Strasbourg 1884 ( e-copy ).

- Wilhelm Fischer: Manteuffel in Alsace-Lorraine and his Germanization policy . M. Bernheim, Basel 1885 ( e-copy ).

- Karl von Lumm: The development of banking in Alsace-Lorraine since the annexation . Justav Fischer, Jena 1891 ( e-copy ).

- Negotiations of the Provincial Committee for Alsace-Lorraine. XX. Session. January – March 1893 . 2. Volume of the meeting reports . Volume 40, R. Schultz and Comp., Strasbourg 1893 ( e-copy ).

- Lexicon entry on Alsace-Lorraine , in: Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon , 6th edition, Volume 6, Leipzig / Vienna 1906, 725–736

Movie

- The Alsatians : A French feature film from 1996 with Irina Wanka and Sebastian Koch . The film consists of four episodes of 90 minutes each and tells the story of Alsace between 1870 and 1953 using the story of fictional families.

Web links

- Reichsland Alsace-Lorraine

- Reichsland Alsace-Lorraine (counties and municipalities) 1910

- Sources, especially nos. 2 and 3, on the political mood in Alsace-Lorraine from 1871 to 1918 ( Memento from July 18, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- German fortresses in the realm of Alsace-Lorraine between 1871 and 1914 - photographic impressions from today

Individual evidence

- ^ Daniel-Erasmus Khan : The German state borders. Mohr Siebeck, 2004, part II, chap. II, section d, p. 66 ff.

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler : German history of society. Volume 3: 1849-1914. C. H. Beck, Munich 1995, p. 1014.

- ↑ Sophie Charlotte Preibusch: Constitutional developments in Alsace-Lorraine from 1871 to 1918. In: Berliner Juristische Universitätsschriften, Fundamentals of Law. Volume 38. ISBN 3-8305-1112-4 , pp. 96ff (108) ( Google digitized version ).

- ^ Rainer Bendel, Robert Pech, Norbert Spannenberger Church and group formation processes of German minorities in East Central and Central Europe 1918-1933 ; P. 63

- ^ Ludwig Adolf Wiese: Memoirs and office experiences. First volume, Berlin 1886, pp. 334–336; quoted from: Gerhard A. Ritter (Ed.): Das deutsche Kaiserreich 1871–1914 (Kleine Vandenhoeck series, 1414). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1977, ISBN 3-525-33384-6 , p. 181: The annexed province of Alsace-Lorraine.

- ↑ Les députés “protestataires” d'Alsace-Lorraine (quoted there in French: “Plaise au Reichstag décider que les populations d'Alsace-Lorraine qui, sans avoir été consultées, ont été annexés à l'Empire germanique par le Traité de Francfort , soient appelées à se prononcer spécialement sur cette annexion. ")

- ^ A b c Hermann Hiery: Reichstag elections in the Reichsland. Droste-Verlag, Düsseldorf 1986, ISBN 3-7700-5132-7 , Chapter 5: Between Autonomists and Protesters (1874-1887) .

- ^ Philipp Ther, Holm Sundhaussen Nationality Conflicts in the 20th Century: Causes of Inter-Ethnic Violence, p. 177

- ↑ Population figures from: Census of December 1, 1910, published in: Vierteljahreshefte and monthly books as well as supplementary books on the statistics of the German Reich. Summarized in: Gerhard A. Ritter, with the collaboration of M. Niehuss (Ed.): Wahlgeschichtliches Arbeitsbuch - materials for statistics of the Kaiserreich 1871-1918. CH Beck, Munich, ISBN 3-406-07610-6 .

- ^ Hermann Hiery: Reichstag elections in the Reichsland. Droste-Verlag, Düsseldorf 1986, ISBN 3-7700-5132-7 , pp. 446 ff. Table 50: Political groups and parties in Alsace-Lorraine (1974-1912).

- ^ Stefan Fisch: Alsace in the German Empire (1870 / 71-1918) . In: Michael Erbe (Ed.) Das Alsace. Historical landscape through the ages. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-17-015771-X .

- ^ Stephanie Schlesier, in: Christophe Duhamelle, Andreas Kossert , Bernhard Struck (Eds.): Grenzregionen. A European comparison from the 18th to the 20th century. Campus, Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 3-593-38448-5 , p. 66.

- ↑ Military History Research Office (Ed.): German Military History in Six Volumes 1648–1938. Munich 1983, Vol. V, p. 27; to the Alsatians, ibid. Vol. IV, p. 260; (on the Social Democrats) and ibid., Vol. IX, p. 496.

- ↑ Jürgen Harbich: The federal state and its inviolability , Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1965, p. 141.

- ^ Law on the Constitution of Alsace-Lorraine. verassungen.de, accessed on October 10, 2013 .

- ↑ Gottlob Egelhaaf: History of the Recent Times from the Peace of Frankfurt to the Present. 7th edition. Carl Krabbe Verlag, Stuttgart 1918, p. 534.

- ↑ "II. - Immediate evacuation of the occupied territories: Belgium, France, Luxembourg and El sa ß-L othringe n. It is to be arranged in such a way that it is carried out within 15 days of the signing of the armistice The German troops who have not evacuated the designated areas within the stipulated period of time will be made prisoners of war. The entire occupation of these areas by Allied and United States forces will follow the course of evacuation in these countries. […] ”, According to the Allied armistice terms. Compiègne, November 11, 1918 , accessed June 28, 2021.

- ↑ Philippe Wilmouth: Images de Propagande, L'Alsace-Lorraine de l'annexation à la Grande Guerre 1871-1919, Vaux, 2013, pp 164-166.

- ↑ Philippe Wilmouth: Memoires en images. Le retour de la Moselle à la France 1918–1919 , Saint-Cyr-sur-Loire 2007, pp. 74–76, 86.

- ^ Scientific Institute of the Alsace-Lorraine in the Empire: Inventory history , University Library Frankfurt am Main

- ↑ See in detail Daniel-Erasmus Khan: Die deutscher Staatsgrenzen. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2004, Part III, Chap. X footnote 25 with further references.

- ↑ Lorraine: Commemoration of expulsions by the Nazis. In: Saarbrücker Zeitung , November 2, 2010, accessed on May 28, 2011.

- ↑ History of the Saarland at a glance. State Chancellery, Saarland Public Relations.

- ↑ Sondages de 2001 des DNA ( Dernières Nouvelles d'Alsace )

- ↑ These recognized religious communities are the Roman Catholic dioceses of Metz and Strasbourg , the Lutheran Protestant Church of the Augsburg Confession of Alsace and Lorraine (EPCAAL), the Israelite consistorial districts of Bas-Rhin (CIBR), Haut-Rhin (CIHR) and Moselle (CIM) as well the Reformed Regional Church ( EPRAL ).

- ↑ Article 7 of the law of June 1, 1924 introducing French civil law in the Bas-Rhin, Haut-Rhin and Moselle departments

- ↑ Cesu: cesu.urssaf.fr (PDF)

- ^ Law Gazette for Alsace-Lorraine. Strasbourg 1872, No. 2, p. 49ff. Online at the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek : urn : nbn: de: bvb: 12-bsb11033602-5 .

- ↑ Meyer's Large Conversation Lexicon . 6th edition, Volume 19, Leipzig / Vienna 1909, pp. 96-99 ( Zeno.org ).

- ↑ a b c d e f Hermann Hiery: Reichstag elections in the Reichsland. Droste-Verlag, Düsseldorf 1986, ISBN 3-7700-5132-7 , Chapter 1: The realm of Alsace-Lorraine as a historical object of investigation, 1. Country and population: language, denomination and nationality, p. 39 ff.

- ^ Complete geographical-topographical-statistical local lexicon of Alsace-Lorraine. Contains: the cities, towns, villages, castles, communities, hamlets, mines and smelting works, farms, mills, ruins, mineral springs, etc. with details of the geographical location, factory, industrial and other commercial activities, the postal service, railroad and telegraph stations and historical notes etc. Adapted from official sources by H. Rudolph. Louis Zander, Leipzig 1872 ( e-copy )

- ^ Ferdinand Mentz: The Germanization of place names in Alsace-Lorraine . ( Memento of November 28, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) From: Journal of the General German Language Association, Volume 31, 1916, pp. 4–8 and 40–46

- ^ Michael Rademacher: German administrative history from the unification of the empire in 1871 to the reunification in 1990. Reichsland Alsace-Lorraine 1871-1919. (Online material for the dissertation, Osnabrück 2006).

- ^ Alfred Wahl, Jean-Claude Richez: L'Alsace entre la France et l'Allemagne, 1850-1950, Paris 1993, p. 251.

- ↑ Folz, above surname: Metz as the German district capital (1870-1913), in: A. Ruppel (Hrsg.): Lothringen und seine Hauptstadt, Eine Sammlung orientierter Aufzüge, Metz 1913, pp. 372–383.