Lorraine (Franconian)

| Lorraine (Franconian) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

France ( Moselle department ) | |

| speaker | 260,457 (1806) - 360,000 (1962) | |

| Linguistic classification |

||

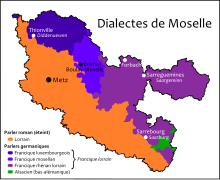

Lorraine dialects - not to be confused with the Gallo-Roman language Lorraine - is a collective name for the Rhine-Franconian and Moselle-Franconian dialects spoken in Lorraine , including Luxembourgish , which belong to West Central German . They are spoken in the northeastern parts of the French department of Moselle and are called " Platt ", "Lothringer Platt" or "Lothringer Déitsch". In French , the terms patois (flat, unspecific) and, since around 1980, francique (Franconian) are used. The German-Lorraine dialects have been strongly pushed back by French since 1945. The Lorraine people who have been born since then often still speak the dialect as a second language, but for those born after 1980, Lorraine is usually at most “grandmother tongue”. Lorraine is therefore threatened with extinction.

history

In the area of Gallia Belgica from the 1st century BC with the Roman conquest, Latin penetrated as the official, written and lingua franca, from the 5th century AD with the advance of Germanic ethnic groups from the east, Alemannic and from the north, Alemannic Franconian . The social, spatial and temporal gradation of the language relationships is unknown. Within the Franconian Empire towards the end of the first millennium after Christ, a linguistic boundary between the Old High German and Old French dialects formed through a peaceful process of equilibrium, which existed as a German-French language border for over 1000 years until the 20th century and continued during this long period shifted only a little to the northeast. The names of localities such as Audun-le-Tiche (German-Oth) and Audun-le-Roman (Welsch-Oth) or the names of the two source rivers, the Nied , Nied Allemande (German Nied) and Nied Française (French Nied).

The government in Paris became interested in the language of its subjects for the first time since the French Revolution . The ideas of freedom, equality and fraternity should now be conveyed to citizens using the French language; all dialects were considered outdated and hostile to education. Since then, this idea has determined French policy towards regional languages. In practice, French was taught in schools in the 19th century and the children often forgot what they had learned or did not understand it at all, as dialect was spoken in the locality and in the family. After 1871 German became the official language and in German-speaking areas school instruction was given in German. When the area returned to France in 1919, French became the only official and school language. In the interwar period and until 1945, numerous newspapers were still published in German. After 1945 the German language was pushed out of the media. In the 1960s, with the advent of television antennas on the roofs of houses, the antennas were directed towards the television stations of Luxembourg and Germany that offered German-language programs. This changed with the following generations, who had only learned French in school after 1945. With the loosening of the language policy around 1990, the station “Radio Melodie” was able to establish itself in Saargemünd with German-language broadcasts. After 1945 in particular, the dialect was frowned upon because of its proximity to German, and more and more parents began not to pass it on to their children. This has been the case almost exclusively since around 1980, so that those born after around 1980 only learn the dialect as a second language or not at all.

The dialect speakers live in an environment with written French. All media (internet, television, radio, newspapers, books) appear in French. This shapes dialect speaking in a special way. Examples (in Forbacher dialect):

- I know all flat talk. Awwer, wammer des schreiwe should eat it hard! ("We can all speak Platt. But if we're supposed to write that, it's difficult.")

- Sinner won? (“Have you moved?” The dialect did not go along with the change from Ihr to Sie in German after 1920.)

- Die Wohnen in de Biseeschtroos (“They live in rue Bizet.” The street name is translated back from French.)

- Dess iss awwer e Scheennie Plaasch ("But that's a beautiful beach." The dialect lacks the word for beach; it is borrowed from French.)

For most children in Lorraine today, Lorraine is no longer their mother tongue, but only "grandmother". It is to be expected that this dialect will only be available as a “ folklore language” in a few decades .

Since the beginning of the 1990s, however, the number of pupils attending bilingual schools or kindergartens, in which, in addition to standard German, the local dialects are also taken into account with at least some teaching units , has risen continuously .

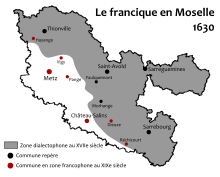

German-French language border

In the German Bellistum of the Duchy of Lorraine and in the small territories of German Lorraine , German was the colloquial and official language in the early modern period . In the south-west and central part of Lorraine with the administrative offices of Metz and Nancy , Romansh dialects and French were spoken . Until the Thirty Years' War , the Franco-German language border ran along a line from Diedenhofen, then in Luxembourg, to Duss in the Saline area in Lorraine . After 1635, the language border gradually shifted to the east, to which the French fortifications and the immigration of Picards contributed. The Duchy of Lorraine came to France in 1766, the last small territories in the 1790s. With the advance of French to the east, former German-speaking communities first became bilingual and finally monolingual French. In 1843, the following municipalities were bilingual in the then Meurthe department : Albestroff , Marimont-lès-Bénestroff , Bénestroff , Guinzeling , Nébing , Vahl-lès-Bénestroff , Lostroff .

From 1871 to 1918, the German-French language border ran in the newly created Lorraine district along a line from Diedenhofen to Saarburg. The towns of Diedenhofen , Sierck , St. Avold , Forbach , Saargemünd and Saarburg in Lorraine were in the German-Lorraine language area . During the time in the German Empire between 1871 and 1918, the city of Metz formed a predominantly German-speaking island within its French-speaking area, the district of Metz, due to the immigration of "Reich German" officials and soldiers .

According to Constant This (The German-French language border in Lothringen, Strasbourg 1887, p. 23 ff.), Whose information is based on observations and inquiries that were collected on the spot, the language border in 1887 ran between the following two lines:

German line

Starting in the northwest: “ Redingen , Rüssingen , roughly from Esch to Ober-Tetingen along the Luxembourg border, Wollmeringen , Nonkeil , Ruxweiler , Arsweiler , Algringen , Volkringen with Weymeringen , through Susingen and Schremingen to Flörchingen , Ebingen , through Ueckingen to Bertringen , Niedergeningen , Obergeningen , Success , Schell , Kirsch bei Lüttingen , Lüttingen , Bidingen , by the ban Ebersweiler to Pieblingen , Drechingen , Buchingen , Rederchingen , Mengen , Gehnkirchen , Brechlingen , Volmeringen , Lautermingen , Helsdorf , Bruchen , Bizingen , Morlingen , Zondringen , Füllingen , Gänglingen , Elwingen , Kriechingen , Maiweiler over Falkenberger spell according precious Bettingen , Einschweiler , Weiler , Beningen , Harprich , Mörchingen , Rakringen , Rodalben , Bermeringen , Virmingen , Neufvillage , Leiningen by Albesdorf according Givrycourt , Münster , Lohr , Lauter Began with MITTERSHEIM , Bert helmet Bettingen , St. Johann von Basel , Gosselmingen , Langd with Stockhaus , Saarburg with homesteads, Bühl , Schneckenbusch , Bruderdorf , Plaine de Walsch , Harzweiler , Biberkirch with Dreibrunnen , Walscheid , Eigenhal , Nonnenberg , Thomasthal , Soldatenthal , from there a line through the Quirintal to the Donon . "

French line

“ Deutsch-Oth , Oettingen , Bure , Tressingen , Havingen , Fentsch , Nilvingen , Marspich , via Susingen and Schremingen to Ober-Remelingen , Nieder-Remelingen , Fameck , through Ueckingen to Reichersberg , Buss , Rörchingen , Monterchen , Mancy , Altdorf , Endorf , St. Bernard , Villers-Bettnach , Brittendorf , Niedingen , Epingen (Charleville) , Heinkingen , Northen , Contchen , Waibelskirchen , Wieblingen , Bingen , Rollingen , Silbernachen , Hemilly , Argenchen , Niederum , Chémery , Thonville , Nieder- and Ober-Sülzen , Landorf , Baronweiler , Rode , Pewingen , Metzing , Conthil , Zarbeling with Liedersingen , Bensdorf , Vahl , Montdidier , through Albesdorf to Dorsweiler , Geinslingen , Losdorf , Kuttingen , Rohrbach , Angweiler , Bisping , Disselingen , Freiburg , Rodt , Kirchberg am Wald , via Bebinger Bann to Imlingen , Hesse , Nitting , Weiher , Alberschweiler , Lettenbach , St. Quirin , Türkstein . "

language

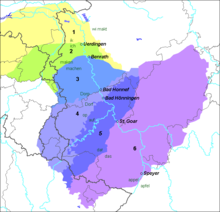

The Lorraine dialects were described in the dictionary of German-Lorraine dialects . Within the dialect continuum, Lorraine belongs partly to the Rhine-Franconian and partly to the Moselle-Franconian or Luxembourgish dialect area, comparable to the dialects in Saarland . Within the dialect continuum, the dialects are understandable at close range, but over longer distances and especially across the Dat-das-line increasingly difficulties in understanding occur. A Forbacher cannot follow a conversation in Diedenhofer Platt, even though the cities are only 50 km apart. However, the dialect is not used for national conversation anyway, but mainly in the family and regional environment.

variants

1. Lower Franconian,

2. Limburgish,

3. Ripuarian,

4. Northern Moselle Franconian (West Moselle Loringian),

5. Southern Moselle Franconian (Lower Lorraine),

6. Rhenish Franconian (Saar Lorraine)

The Isogloss op / of separates the Luxembourgish variant of the Moselle Franconian from the Moselle Franconian. Emil Guelen (1939) calls the dialect spoken west of the Moselle West Moselle Lorraine, the eastern variant Low Lorraine.

Example for the West Moselle Lorraine:

All men can fräi a mat deer changed Dignitéit to deene selwechte right op d'Welt. Jiddereen huet säi understanding a säi Gewësse krut a should act on a close Geescht vu Bridderlechkeet deenen anere géintiwwer.

Zeurange, Grindorf, Flastroff, Waldweistroff, Lacroix, Rodlach, Bibiche, Menskirch, Chémery, Edling, Hestroff remain on the west Moselle Lorraine side. Schwerdorf, Colmen, Filstroff, Beckerholtz, Diding, Freistroff, Anzeling, Gomelange, Piblange remain on the Lower Lorraine side.

Example for Lower Lorraine (Leï, la, lõrt = here, there, there):

Leï, la, lõrt - dat isch the Bolcher Wuat;

And whoever can't do that Bolcher Wuat,

het kän Däl am Bolcher Bann.

The isogloss dat / das separates the Lower Lorraine from the Saar Lorraine. Emil Guelen (1939) calls the dialect spoken east of the Nied the Saar-Lorraine.

Ham-Sous-Varsberg, Varsberg, Bisten, Boucheporn, Longeville, Laudrefang, Tritteling, Tetting, Mettring, Vahl-lès-Faulquemont, Adelange remain on the Lower Lorraine side, Creutzwald, these, Carling, Porcelette, Saint-Avold, Valmont, Folschviller, Lelling, Guessling-Hémering, Boustroff.

Example of Saar Lorraine:

All people are free ùnn wìt derselwe Dignité ùnn deselwe Reschde born. Se sìnn gifted àn Venùnft ùnn mìnn Zùenänner ìm Gäscht von Brìderlichkät hannele.

Bilingual traffic signs

See also

literature

- Hervé Atamaniuk, Marielle Rispail, Marianne Haas: Le Platt lorrain pour les Nuls , First, 2012, ISBN 2754036067 .

- Hervé Atamaniuk, Günter Scholdt (ed.): From Bitche to Thionville: Lorraine dialect poetry of the present. Röhrig Universitätsverlag, St. Ingbert, 2016, ISBN 978-3-86110-593-0 .

- Max Besler: The Forbach dialect and its French components , Forbach, 1900, OCLC 252462798 , ( Online )

- Gérard Botz: Histoire du francique en Lorraine - Lothringer Platt , Gau un Griis, 2013, ISBN 978-2-9537157-6-7 .

- Follmann: The dialect of the German-Lorraine and Luxembourgers, A. Konsonantismus , 1886 ( online ); Part II: Vocalism , 1890, ( Online )

- Marianne Haas-Heckel: Caretaker book vum Saageminner Platt - Lexique du dialecte de la région de Sarreguemines , Confluence, 2001, ISBN 2909228126 .

- Karl Hoffmann: Phonology and inflection theory of the dialect of the Moselle region from Oberham to the Rhine Province , inaugural dissertation, Metz, 1900 ( Online (US) )

- Walter Hoffmeister: Language change in East Lorraine: Sociolinguistic study of the language choice of students in certain speaking situations , 1977, ISBN 9783515025676 .

- Jean-Louis Kieffer: Le Platt Lorrain de poche , Assimil , 2006, ISBN 2-7005-0374-0 .

- Daniel Laumesfeld: La Lorraine francique: culture mosaïque et dissidence linguistique , L'Harmattan, 1996, ISBN 2-7384-3975-6 .

- Sabine Legrand: On the situation of language policy in Eastern Lorraine , 1993, OCLC 922527272

- Hélène Nicklaus: Le platt: Une langue , Pierron, 2008, ISBN 2-7085-0343-X .

- Hélène Nicklaus: Le Platt - Le francique rhénan du Pays de Sarreguemines jusqu'à l'Alsace , Pierron, 2001, ISBN 2-7085-0277-8 .

- Manfred Pützer, Adolphe Thil, Julien Helleringer: Dictionnaire du parler francique de Saint-Avold , Éditions Serpenoise, 2001, ISBN 2876925060 .

- Alain Simmer: Aux sources du germanisme mosellan. La fin du Mythe de la colonization franque , Metz, Éditions des Paraiges, 2015, ISBN 979-10-90282-05-6 .

- Alain Simmer: Peuplement et langues dans l'espace mosellan de la fin de l'Antiquité à l'époque carolingienne , Université de Lorraine , 2013, ( online ).

- Straw: language contact and language awareness: a sociolinguistic study using the example of East Lorraine , 1993, ISBN 382335048X .

- Straw: Language choice in Petite-Roselle (East Lorraine) , 1988, OCLC 726787137 , ( online )

- Nikolaus Tarral: Phonology and form theory of the dialect of the canton Falkenberg in Lothr. , Inaugural dissertation, Strasbourg, 1903, OCLC 609523278 , ( online )

Individual evidence

- ↑ Sébastien Bottin, Mélanges sur les langues, dialectes et patois , Paris, 1831. (Moselle: 218.662 - Meurthe : 41.795)

- ↑ INSEE

- ↑ Open house at Radio Melodie in Saargemünd

- ^ A b Henri Lepage: Le département de La Meurthe: statistique, historique et Administrative - Deuxième partie - 1843

- ^ A b Constant This: The German-French language border in Lothringen , Strasbourg 1887, p. 23ff. On-line

- ↑ Michael Ferdinand Follmann: Dictionary of German-Lorraine Dialects, Strasbourg 1909, p. VII. Variant ibid p. 333: Leï, la, loert - Dat ben dreï Bolicher Wôrt; Anyone who can chat with you, should give Bolchen a hand.

Web links

- Lorraine to listen to

- Dictionary of German-Lorraine dialects in the dictionary network

- Website of the association Gau un Griis (Bouzonville)

- Website of the association Culture et Bilinguisme de Lorraine - Bilingual, our future

- Website of the Association pour le Bilinguisme en Classe dès la Maternelle - ABCM Bilingualism

- Plattweb.free.fr ( Memento of February 1, 2006 in the Internet Archive )