Duchy of Nassau

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

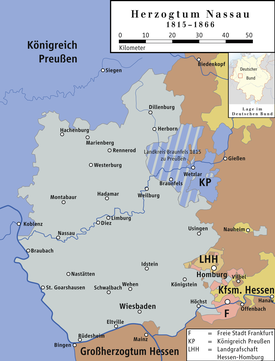

The Duchy of Nassau was one of the member states of the German Confederation . The state existed from 1806 to 1866 and was on the territory of today's federal states of Hessen and Rhineland-Palatinate . Its capital was Wiesbaden , and until 1816 it was also Weilburg . Although the area has long ceased to be a political entity, the historical and linguistic ties of the "Nassauer Land" region are continued to this day by associations, churches and regional banks and are also used commercially by some companies.

geography

The area of the duchy was essentially congruent with the low mountain ranges Taunus and Westerwald . The southern and western borders were formed by the Main and the Rhine , while the Lahn separated the two low mountain ranges slightly north of the center of the country . Neighbor to the east and south was the Grand Duchy of Hesse , to the east the Landgraviate of Hesse-Homburg and the Free City of Frankfurt , and to the west was the Rhine province belonging to Prussia , to which the Wetzlar district east of Nassau also belonged as an exclave .

population

When it was founded in 1806, the duchy had 302,769 inhabitants. The subjects were mostly farmers, day laborers or artisans. In 1819 seven percent of Nassau residents lived in places with more than 2,000 inhabitants, the rest in 850 smaller towns and 1,200 individual farms. After Wiesbaden with around 5000 inhabitants, Limburg an der Lahn was the second largest city with around 2600 inhabitants. By 1847 Wiesbaden had grown to 14,000 inhabitants, Limburg to 3400. The third largest city was Höchst am Main .

history

Emergence

The house of Nassau had disintegrated into a large number of sidelines several times in the course of its almost thousand-year history. By the 18th century, however, the three main lines of the small principalities of Nassau-Usingen and Nassau-Weilburg as well as Nassau-Diez (later Nassau-Orange) with the much larger territory in the Netherlands and Belgium had developed. From 1736 onwards, several contracts and agreements were concluded between these lines ( Nassau Heritage Association ) , which were intended to prevent further splitting and to coordinate the common political approach. In this context, the administrative structures of the individual territories were adjusted and the foundation for the later merger was laid.

After the First Coalition War , Nassau-Diez lost its possessions in Belgium and the Netherlands as well as the two small principalities their lands on the left bank of the Rhine to France. Just like the other secular German principalities, the Nassauer were to be compensated with secularized spiritual areas. To this end, they conducted negotiations at the Rastatt Congress (1797) and in Paris, with the aim of preserving above all areas of the Electorates of Mainz and Trier . The two princes decided to closely follow Napoleon , probably also under the impression that their relative Wilhelm I of the Netherlands lost his home country after he had fought against France on the Prussian side. The Nassau princes tried to prove themselves as loyal vassals by willingly and often in excess of the requirements they provided troops for Napoleon's campaigns.

The Reichsdeputationshauptschluss of 1803 largely corresponded to the wishes of the two small Nassau principalities. Nassau-Orange had previously agreed in separate negotiations with Napoleon . As a replacement for the former county of Saarbrücken, Nassau-Usingen received two thirds of the county of Saar Werden , the rule of Ottweiler and smaller areas (a total of 60,000 residents and 447,000 guilders tax income per year) from Kurmainz Höchst, Königstein , Cronberg , Lahnstein and the Rheingau , from Kurköln some offices on the right bank of the Rhine, from Bavaria the sub-office Kaub , from Hessen-Darmstadt the rule Eppstein , Katzenelnbogen , Braubach , from Prussia the former counties Sayn-Altenkirchen and Sayn-Hachenburg and several Electoral Mainz monasteries. With this, Nassau-Usingen made up for its population loss and gained additional tax income of around 130,000 guilders. Nassau-Weilburg gave up Kirchheim and Stauf in the Palatinate as well as its third of Saar Werden (15,500 inhabitants, 178,000 guilders tax revenue). In return, it received numerous small Electorate Trier possessions, including Ehrenbreitstein , Vallendar , Sayn , Montabaur and Limburg , three abbeys and the Limburg Monastery . This added up to 37,000 residents and 147,000 guilders in annual taxes. In the course of the development process, the chamber property of the Princely House grew considerably to more than 52,000 hectares of forests and agricultural area. These domains made up 11.5 percent of the country's area and provided the largest part of the state's revenue with a profit of around one million guilders per year.

Even before the actual Reichsdeputationshauptschluss, in September and October 1802, the two Nassau principalities occupied the territories of Electoral Cologne and Mainz with troops. In November and December, civil administration officials took possession of the area, with the previous civil servants and residents being sworn in again. According to the reports of the Nassau officials, the new rule was welcomed by the population in most areas, or at least accepted without protests, as the Nassau principals were considered to be much more liberal than the previous ecclesiastical principalities. From December 1802 to September 1803 the wealthy monasteries and monasteries were also dissolved: the Antoniterkloster Höchst , the St. Georgenstift Limburg, the Cistercian monasteries Eberbach , Tiefenthal and Marienstatt , the Premonstratensian monastery Arnstein and the Benedictine monastery Schönau . The dissolution of the dispossessed monasteries dragged on until 1817, as the state had to take over a pension obligation for the monks and conversations with the dissolution . From October 1803 to February 1804 there was first the partly military occupation, then the mediation of numerous imperial knightly territories and territories immediately adjacent to the empire . It was not until August and September 1806 that the possession was legally enforced by edict based on the Rhine Confederation Act . This process aroused considerable resistance among the imperial knights, but it remained without consequences, not least because the Nassau princes were supported in taking possession of French officials and soldiers.

On July 17, 1806 Prince Friedrich August von Nassau-Usingen and his cousin Prince Friedrich Wilhelm von Nassau-Weilburg joined the Confederation of the Rhine . In return for this, Friedrich August, the eldest of the House of Nassau , received the title of sovereign Duke of Nassau . Friedrich Wilhelm was given the title of sovereign Prince of Nassau . The princes made the decision to finally unite their two principalities into one duchy . This was formally completed on August 30, 1806. This decision was favored by the fact that Friedrich August had no male descendants and that the much younger Friedrich Wilhelm would have become his heir anyway. Minister of State were Hans Christoph Ernst von Gagern and Ernst Franz Ludwig Marschall von Bieberstein . From 1811 until his death, von Bieberstein managed the official business alone.

Both sub-duchies initially had their own government in Wiesbaden and Weilburg. A third government existed in Ehrenbreitstein for the areas of the counties Sayn-Hachenburg and Sayn-Altenkirchen. By 1816 these governments were united in Wiesbaden. The new country was formed from more than 20 previously independent parts and territories, secularized areas and formerly subordinate to the Reich, with different creeds and interests.

The dukes and their government avoided the threat of breaking up the duchy after the fall of Napoleon in 1812/13 by closely leaning towards Austria, which joined the Allies in August 1813. On November 23, 1813, Nassau went over to the Allies at the headquarters in Frankfurt. In the accompanying treaty, Russia, Austria and Prussia guaranteed the sovereign continued existence of the Duchy of Nassau. In return, the duchy agreed to assign territories as part of a reorganization of Germany, which should take place against compensation. In addition, the dukes in Prussia won Heinrich Friedrich Karl vom und zum Stein as a supporter, although he was one of the noblemen mediated in the area of the duchy. His initial protest turned into sustained support for the duchy after substantial compensation from the Nassauer.

In 1815 the area grew again. When the Nassau-Orange line received the Dutch royal crown on May 31, it had to cede its home country to Prussia, which on the following day passed part of it on to the Duchy of Nassau. As part of the associated agreement, there were further smaller territorial shifts, in the context of which Nassau gave border strips near Siegen and Wetzlar to Prussia and received the Lower County of Katzenelnbogen in return. After the territorial development was completed, the opposition of the mediatized houses, which until then had been pushing for their territories to be restored, subsided. The last time it formed was in the state parliament's Herrenbank.

Reform era

In the style of enlightened absolutism, but based on the legal situation in the French-occupied territories, the sovereigns decreed a number of reforms that had already been carried out in other German territories. Minister of State von Bieberstein had done the drafting in consultation with Freiherr vom Stein. The reforms included the abolition of serfdom (1806), the admission of confessional mixed marriages (1808), the introduction of the freedom to travel and residence (1810) and a fundamental tax reform, which in 1812 a total of 991 direct taxes through a uniform and socially graded basic and Trade tax replaced. Dishonorable corporal punishments were lifted and the cultural ordinance promoted the independent cultivation of land.

Due to religious heterogeneity, Nassau introduced simultaneous schools with the school edict of March 24, 1817, and on March 14, 1818 - for the first time in Germany - a nationwide state health system, see pharmacy in Nassau . As one of the last major reforms, freedom of trade was introduced in 1819 .

After a transition period with four districts, the new duchy was divided into the three administrative districts of Wiesbaden, Weilburg and Ehrenbreitstein on August 1, 1809 . The number of offices was reduced from 62 in 1806 to 28 in 1817. These reforms were not only about modernizing the existing administration, but also about standardizing the integration of the numerous new areas with their administrations structured very differently. The highest levels of justice and administration were separated. Wiesbaden became the location of the Higher Appeal Court, Dillenburg that of the Court of Justice. In 1822 Wiesbaden received a second court court. Later there were two criminal courts in the two cities.

The health system was unique in the German states. The Medical Ordinance of March 14, 1818 established a state-employed medical councilor with assistants, an official pharmacy (in practice, however, often responsible for several offices) and several midwives for each office. Doctors had to treat poor residents at reduced rates.

The 1814 Constitution

On September 2, 1814, a constitution was also issued by decree. It was the first modern constitution of a German state. Due to the now - albeit very limited - parliamentary participation, especially in tax collection, it is referred to in the terminology of the time as the land estates constitution , whereby the term land estates still falls back on corresponding traditions from the Old Kingdom. The constitution guaranteed freedom of property, religious tolerance and freedom of the press. It was significantly influenced by Heinrich Friedrich Karl Freiherr vom Stein. The princes had insisted on his cooperation because he was one of the imperial knights expropriated by them and the resistance from the knighthood should be weakened by his involvement.

The legislation of the restoration period , especially the Karlsbad resolutions of 1819, meant a renewed dismantling of civil liberties in Nassau as well. The Nassau government, especially Bieberstein, decidedly supported the restoration. The decisive factor was, not least, an assassination attempt on District President Carl Friedrich Emil von Ibell on June 1, 1819. It fueled fear of a possible overthrow among the Duke and government, to which they wanted to react with a decided suppression of democratic aspirations.

The estates

According to the constitution of 1814, the parliament consisted of two chambers: an assembly of state deputies and a gentleman's bank. The eleven-strong gentleman's bench was formed from the princes of the Nassau family and representatives of the nobility. The 22 members of the second chamber (state assembly of deputies) were mostly elected according to the census system, but had to be landowners, apart from three representatives of the clergy and one of the teachers.

Despite protests and inspiration from the citizens, the duke did not schedule the first elections until the beginning of 1818, four years after the constitution was promulgated. This late date was intended to prevent Parliament from participating in the basic establishment of the duchy. 39 nobles and 1,448 bourgeois landowners as well as 128 wealthy townspeople were eligible to vote . Measured by the population of the duchy, the proportion of those eligible to vote was low compared to other German territories.

On March 3, 1818, the estates met for the first time.

The Nassau Domain Dispute

When the duchy was founded, Bieberstein established a strict fiscal separation between the general domain treasury and the state tax treasury. The domains , including manors and property in general, mineral springs and baths as well as still existing tithes and land charges , were understood as ducal household goods that could neither be used to finance state expenditure nor were subject to co-determination by the estates. There was already clear criticism of this regulation in the founding years. In addition to Freiherr von Stein, District President Ibell criticized this again and again in letters to Bieberstein and petitions to the Duke. His stubborn attitude was one of the reasons for Ibell's impeachment in 1821. The handling of the domains was also criticized in the press in other German countries and in petitions from the residents. Particularly in the previously non-Nassau parts of the country, the petitions were used as an expression of general criticism of the Nassau administration.

In the following years there were repeated disputes between and within the estates and with the government about the separation between ducal and state property. The conflict only broke out openly after unrest broke out in neighboring countries during the July Revolution of 1830 . In 1831 the government then banned petitions from being submitted to the Duke and held a maneuver in the Rheingau with Austrian troops from the Mainz fortress. The following session of the so far less active state estates was characterized by an unusually large number of reform initiatives, of which, however, few were implemented. The domain question also came back into focus. On March 24th, the deputies of the second chamber presented a declaration that the domains are the property of the general public. The government then called a public meeting on the subject, at which it announced a contrary statement. In order to possibly put down the following uprisings, the neighboring Grand Duchy of Hesse made several hundred soldiers available. In Nassau, however, things remained calm. Within the country and in the neighboring principalities, there was a public dispute with newspaper articles and pamphlets from both sides.

On the side of the deputies, Chamber President Georg Herber became the main figure in the conflict, especially with a pamphlet published on October 21, 1831 in the foreign "Hanauer Zeitung". At the end of 1831, the Nassau court and appeal court began investigations against Herber. On December 3, 1832, he was finally sentenced to three years imprisonment for "insulting the regent" and "injuries" against Bieberstein. On the night of December 4th to 5th, the President of the Chamber was arrested in his bed. On January 7, 1833, he was released on bail. Herber's lawyer August Hergenhahn , later revolutionary Prime Minister Nassaus, tried to achieve a reduction in the sentence, but this was rejected. The three-year imprisonment was not carried out because the seriously ill Herber died on March 11, 1833.

In the course of 1831 the ducal government had already prepared an enlargement of the manorial bank of the estates and ordered it by edict of October 29, 1831. The bourgeoisie had thus been made a minority and in November 1831 were unsuccessful in their attempt to refuse to collect taxes. Likewise, the Herrenbank voted down a lawsuit against Bieberstein aimed at by the commoners, with which the enlargement of the Herrenbank should be punished. In the months that followed, there were repeated meetings, rallies, newspaper publications (especially abroad) and leaflets from the various parties to the conflict. On the government side, officials who had expressed their sympathy for the bourgeois camp were reprimanded or dismissed and liberal magazines were banned from abroad.

In March 1832 the second chamber was newly elected. However, the bourgeois deputies demanded that the Herrenbank be restored to its previous state. When the government refused to do so, the elected stopped the session and left the congregation on April 17th. The three clergymen, the teacher and a remaining deputy declared the rest of their rights forfeited and approved the ducal taxes.

Change of ruler

After the domain dispute, a largely political calm ensued in the duchy. After the death of Marshal von Bieberstein, Nassau joined the German Customs Union in 1835, which the minister had vigorously opposed. In 1839 Duke Wilhelm also died, whereupon his 22-year-old son Adolph took over the rule. Adolph moved his residence to the Wiesbaden City Palace in 1841 and married the Russian Grand Duchess Elisabeth Michailowna in January 1845, who died a year later in childbirth, in honor of which he had the Russian Orthodox Church built on Neroberg that same year . In 1842 Adolph was one of the initiators of the Mainz Aristocracy Association , which wanted to promote colonization in Texas, but failed.

In 1844, a wave of club foundations began in Nassau, especially commercial and gymnastics clubs. They remained apolitical at first, but were to play a role in the revolution that followed. Wiesbaden also became one of the centers of German Catholicism . The government ventured tentative reforms in 1845 with a somewhat more liberal municipal law and in 1846 with a law on jury courts. In 1847, the estates demanded freedom of the press and a game damage law, whereby they took up the complaints of the rural population about the consequences of the sovereign hunting sovereignty.

The revolution of 1848

After the February Revolution of 1848 , Nassau, like the rest of Europe, was hit by a revolutionary wave. On March 1st, a liberal circle gathered around the lawyer and deputy August Hergenhahn in the Wiesbaden hotel "Vier Jahreszeiten" to draw up a moderate catalog of national liberal demands on the ducal government. It included civil liberties, a German national assembly and a new right to vote. The following day, the “ Nine Demands of Nassau ” were handed over to Minister of State Emil August von Dungern , who immediately approved the armament of the people , freedom of the press and the convening of the Second Chamber to deliberate on reform of the electoral law. The remaining decisions were to be left to the Duke, who was in Berlin at the time. The almost Europe-wide revolutionary climate met with widespread dissatisfaction with the political system and their own living conditions in the Nassau rural population. This mood was based on several previous bad harvests and the resulting pauperism as well as the fact that in Nassau, compared to other countries, there were a particularly large number of sovereign forest and hunting privileges, the replacement of the tithe in Nassau was particularly slow and the participation of the residents in the local population was particularly low had been.

After a call from Hergenhahn, around 40,000 people gathered in Wiesbaden on March 4th. A conflict became clear, which should also determine the following development: While the circle around Hergenhahn hoped for confirmation of their demands by acclamation , the rural population, some of whom were armed with scythes, flails and axes, was primarily concerned with the abolition of old feudal burdens and a relaxation of the forest and hunting laws. As the crowd moved restlessly through the city, the Duke announced from the balcony of his residence that he would meet all requirements. Then the crowd dispersed peacefully again.

With the announcement of the freedom of the press, 13 political newspapers appeared within weeks, five of them in Wiesbaden alone. Numerous official gazettes in the rural regions also began to print political texts.

From the second week of March, the electoral reform moved into the focus of political events. The most important demand of the Liberals was that the right to stand for election should not be tied to a lower limit of wealth. On March 6, the Second Chamber met to deliberate on this matter. When the Herrenbank wanted to deal with the right to vote, protests broke out among the Wiesbaden population. In any case, up to 500 residents gathered in Wiesbaden in the evening to publicly debate the question of electoral law. Smaller gatherings also took place in other Nassau cities. However, by the middle of the month, these public discussions subsided. In terms of content, the second chamber agreed that the future parliament should include only one chamber with 40 to 60 members and that the census should be abolished for both active and passive voting rights. The main controversial issue was whether the MPs should be chosen directly or by electors . A draft law was presented on March 20, which the second chamber finally reached on March 28. The meeting decided on electors with 18 votes to three. On April 5, the electoral law came into effect. It stipulated that every hundred residents should elect an elector, who in turn should elect the representatives in 14 constituencies. Previously excluded groups, such as nobles, civil servants, pensioners and Jews, were also given the right to vote. Those who received poor relief or who filed for bankruptcy were not allowed to vote. All residents were allowed to become MPs, with the exception of high administrative, military and court officials.

Meanwhile, on March 31, the pre-parliament met in the Paulskirche in Frankfurt . 15 of his deputies came from the second chamber of the Nassau parliament, two from the Herrenbank. To this end, nine other citizens of the duchy were appointed to the pre-parliament.

Meanwhile, chaotic conditions developed in the rural regions. Numerous civil servants had given up their functions with the beginning of the revolution, so that there was hardly an orderly administrative system. The ducal government had also contributed to this with hectic activities such as amnesties, which particularly affected hunting, field and forest offenses, the concession of free mayor elections , the abolition of the last labor burdens and the removal of unpopular administrative officials, which were intended to keep the population calm. As a result, the farmers in particular stopped paying taxes completely and drove out foresters. Young officials and teachers who represented radical democratic views often appeared as agitators. In the cities, the population often reacted to the rampant lawlessness by setting up vigilante groups . A central security committee for the whole of Nassau was established in Wiesbaden, which was headed by August Hergenhahn and enjoyed a certain authority throughout the duchy. Hergenhahn thus developed into the final, moderately liberal leader of the revolution in Nassau and also won the trust of Duke Adolph. After Emil August von Dungern resigned as Minister of State, the Duke transferred the business of government to Hergenhahn on April 16.

As the elections for the Nassau parliament approached, political associations and, eventually, parties began to form. After the Liberals, at the instigation of Limburg Bishop Peter Josef Blum , Catholic associations were formed from the end of March, especially in rural areas. They had the clearest program among the parties, based on the 21 demands made by the bishop on March 9th. Pastoral letters and church services also served as platforms for church election advertising (see History of the Diocese of Limburg ). On April 4, the “Committee of the Republican Society” appeared in Wiesbaden with a radically liberal leaflet as the first party to defend itself against the Catholic election agitation. A day later, a democratic-monarchist opposing party, which was formally founded on April 7th, spoke up with a special issue of the “Nassauische Allgemeine”. On April 5, there was severe turbulence around the formation of a Wiesbaden committee to prepare for the election. The radical liberals had called for a meeting at 1 o'clock in the morning at which the electors were to be determined, and had already drawn up a list of candidates for this purpose. The moderates achieved a two-hour delay in the morning and used the time to draw up their own list, which was approved by a large majority during the vote.

In the weeks that followed, the ducal administration began preparing for the elections to both the Landtag and the German National Assembly . Since such a task had to be mastered for the first time, there were extremely cumbersome procedures in many places to compile the electoral roll. There were protests by the population and the newspapers because of the conditions for the right to vote, which were perceived as unfair. In particular, there was a lack of understanding that the sons of craftsmen and farmers of legal age were not allowed to vote as long as they worked in their parents' business.

On April 18, the primary elections to determine the electorate finally took place. They were chosen in the individual cities and communities by the personally assembled voters. The total number of eligible voters among the 420,000 inhabitants of the Duchy of Nassau cannot be determined with certainty. Estimates vary between 84,000 and 100,000. The voter turnout ranged between low percentages and almost complete attendance of voters in some smaller communities. However, participation tended to be higher in cities than in rural areas.

Numerous procedural errors were reported from the election meetings. Philosophical programs played a subordinate role in the choice of electors. Often, promises of lower taxation dominated the debate during election meetings. In most cases, notables such as mayors, teachers, foresters or, especially in the Catholic Westerwald, clergy prevailed. The Catholic camp had provided its supporters with preprinted ballot papers on which the Catholic candidates were noted. This procedure was expressly permitted in the electoral law, but met with strong criticism from the Liberals.

On April 25, the approximately 4,000 electors first elected the six Nassau MPs for the National Assembly. The search for suitable and willing candidates proved difficult. The Wiesbaden election committee, representing the moderate liberals, the Catholic Church with its associations and the various ideologically oriented newspapers, found applicants for the six constituencies with great difficulty. The list of the electoral committee includes only civil servants.

Without any major disputes, procurator Carl Schenck from Dillenburg won constituency 1 (Rennerod) in the north of the duchy with 76 percent of the vote, and government councilor Friedrich Schepp won constituency 4 (Nastätten). With 90 percent of the votes, Schepp achieved the best result among the Nassau MPs. In constituency 2 (northwest, Montabaur) there was a much more violent election campaign, but Baron Max von Gagern prevailed with 82 percent of the vote. Gagern ran as a candidate for the Liberal Committee, but was at the same time a staunch Catholic and a trusted advisor to the Duke. This position between the camps offered areas of attack for Catholic and liberal campaigns against him, but these ultimately did not succeed, especially since he also received the support of the Church. Friedrich Schulz , the committee candidate for constituency 3, which is centrally located around Limburg, was also controversial . As the editor of the “Lahnboten”, the Weilburg vice-principal was in the political debate and represented a reformist line that, in his opinion, should result in a republic. Because of these extensive plans, some of which were criticized as “fantastic”, Schulz was also controversial within the liberal movement. In the end, Schulz achieved the second-best result in the Nassau constituencies with 85 percent. The most radical views of the six MPs were represented by government councilor Karl Philipp Hehner , who conquered constituency 5 (Hintertaunus, Königstein). The former fraternity member was temporarily dismissed from civil service in 1831 because of his convictions, but in March 1848 had risen to become one of the highest administrative officials. Hehner saw a constitutional monarchy only as a temporary solution and aimed for a republic in the medium term. Probably because of this radical opinion, he received only 61 percent of the votes in his constituency. In constituency 5, in which Wiesbaden was located, August Hergenhahn became the leader of the revolution in Nassau, who received 80 percent of the vote.

In the course of 1848, the Nassau MPs in the National Assembly, with the exception of Schenk, joined the various fractions that were forming: Gagern, Hergenhahn and Schepp from the moderately conservative Casino , Schulz and Hehner from the moderately left-wing Westendhall . In the process of disintegration of the National Assembly, Max von Gagern resigned his mandate on May 21, 1849 together with 65 other monarchist deputies, shortly afterwards Hergenhahn, Schepp and Schenk. Hehner and Schulz remained its members until the violent dissolution of the rump parliament in June 1849 in Stuttgart.

In the election campaign for the state elections on May 1st, which was also carried out by the 4,000 electors, local interests played a considerably greater role than in the previous round. The parties and associations also hardly appeared. Again, mainly administrative officials and mayors, and occasionally merchants, industrialists and farmers were elected. Noticeably few decidedly Catholic MPs and not a single Catholic clergyman were represented. The new Nassau parliament met for the first time on May 22, 1848. Over the summer, groups began to form in this assembly according to the left-right scheme (see: List of the members of the estates of the Duchy of Nassau (1848-1851) ).

The unrest in the duchy had hardly abated after the elections. They reached a new high in July 1848 after disputes over the Duke's right to veto decisions by Parliament. While the left in the state parliament did not recognize this right, parliamentary rights and the government resolutely contradicted it. Soon this dispute escalated into civil unrest. Hergenhahn finally requested Prussian and Austrian troops from Mainz, which put down the uprising in Wiesbaden. In September, after street battles in Frankfurt, federal troops occupied part of the Taunus.

In parallel with the MPs, the political club and press landscape began to form more ideologically and to become more active. Numerous petitions and rallies took place in the second half of the year. The "Freie Zeitung" became the mouthpiece of the left wing of the National Assembly during the summer and increasingly criticized both the Prussian and Nassau governments. The "Nassauische Allgemeine" gave up its neutral course shortly afterwards and joined the proponents of a constitutional monarchy, as did the Weilburg "Lahnbote". In 1848, however, the revolutionary dynamism was slowing down. With the exception of the “Freie Zeitung” and the “Allgemeine”, all papers stopped appearing in the second half of the year because sales fell rapidly and the ducal government began to repress. In view of this development, the “Nassauische Allgemeine” became increasingly dependent on the government in terms of finance and content. From the end of 1849 there was again a comprehensive press censorship .

The numerous political associations that were formed by autumn 1848 represented mostly democratic positions, including several gymnastics and workers' education associations in addition to the exclusively political ones . The first establishment of an explicitly democratically oriented political association was that of the Bürgererverein an der lower Weil, which was founded in mid-July at the misery mill near Winden at the instigation of Friedrich Snell . As the organizer of meetings with up to 2000 participants, the citizens' association on the lower Weil quickly became the most influential political group. As a result of the September riots in Frankfurt, the meetings of the association were banned, which probably led to its dissolution at the turn of the year 1848/49. The founders of political associations, especially in rural areas, were often comparatively wealthy landowners and traders. One focus was initially in the Taunus and Main region, while the Westerwald remained largely free of democratic organizations. Religious associations, especially Catholic ones, dominated there.

On November 12th, the democratic associations formed the “Kirberg Association” and thus formed a common umbrella organization. With the beginning of the reaction, there were numerous new foundations, so that the Kirberg Association had around 50 member associations at the end of the year, some with several sub-associations. In the following months, however, the democratic association movement quickly collapsed again. From the middle of 1849 onwards, democratic associations were barely active, especially since there had been violent clashes between radical republicans and moderate democrats as part of the imperial constitution campaign . Local approaches to arming the people in April and May 1849 were not implemented. A few associations also represented constitutional monarchist goals. They gave a superordinate structure on November 19, 1848: The Nassau and Hessian constitutional associations renamed themselves to "German associations" on this date and founded a joint umbrella organization based in Wiesbaden.

After the failure of the National Assembly, the beginning of the reaction era led to clashes between Prussia, Austria and the smaller German states. The Duchy of Nassau was one of the few smaller principalities that supported the Prussian side and supported the plans to convene the Union Parliament in Erfurt. Prime Minister Hergenhahn himself advised the Duke to do this and then asked for his release on June 7, 1849, because as a member of the Paulskirchen Church in this position he would have made it difficult to change course. On December 3, 1849, the ducal government passed a corresponding electoral law with four Nassau constituencies according to the three-class suffrage.

Although the political movements had their heyday behind them, there was still an election campaign for the upcoming polls. Constitutional as well as government and “Nassauische Allgemeine” tried to achieve the highest possible voter turnout and thus legitimacy for the Prussian unification plans for Germany under monarchist auspices. The corresponding Gothaer program came about largely at the instigation of Max von Gagern. August Hergenhahn also took part in the associated meeting in June 1849. On December 16, the constitutional officials organized a first large electoral meeting in Wiesbaden, at which they put forward an election proposal. The Democrats, however, tried to keep the turnout as low as possible and insisted on the implementation of the Frankfurt constitution. In June 1849 they organized popular assemblies across Nassau with this aim. The largest assembly with around 500 participants formulated ten demands on June 10th in Idstein, which included the withdrawal of the Nassau troops from Baden, Schleswig-Holstein and the Palatinate, which were fighting revolutionary movements there as federal troops . In addition, the National Assembly should be completed again and given its powers. The political club Catholicism had already collapsed by this time. The church itself made no move to influence the election.

Preparations for the election to the Erfurt parliament began in December 1849. On January 20, 1850, the primary election of the electors took place in Nassau. Because of the higher voting age, the number of those eligible to vote is likely to have been slightly lower than in 1848. The turnout fluctuated between one and 20 percent. Only two constituencies with participation of over 60 percent are proven. In some places, only the officials took part in the polls. In at least 27 of the 132 primary electoral districts, the election could not take place at all due to a lack of participation and was rescheduled on January 27th. Civil servants were almost exclusively chosen as electors. In the days that followed, the constitution made proposals for the MPs to be elected. On January 31, the electors named Carl Wirth , the administrator from Selters , Max von Gagern , August Hergenhahn and Prince Hermann zu Wied as MPs. Although Prince zu Wied was himself a nobleman , he was still considered the most liberal of the four deputies.

The Nassau state parliament was dissolved on April 2, 1851 after ongoing disputes between right and left over the budget approval on the order of the duke. This made it one of the longest-running state parliaments that had formed during the German Revolution.

The restoration

Domestically, Duke Adolph began to implement the response time program after a brief period of rest. After repeated clashes between the Duke and the only moderately conservative Prime Minister Friedrich Freiherrn von Wintzingerode , the latter resigned at the end of 1851. He was succeeded on February 7, 1852 by Prince August Ludwig von Sayn-Wittgenstein-Berleburg . With his help, the Duke restricted the remaining freedoms on the administrative path in the following years and began to remove liberals from the civil service. So all political associations were gradually banned by mid-1852.

As early as 1849, the government had submitted a draft to parliament for a new electoral law, which, among other things, provided for a two-chamber system in which the first chamber should be elected by the wealthiest citizens. This draft sparked opposition from the Liberals, while the Constitutionalists endorsed it. After months of electoral law, the government presented a draft for a parliament with only one 24-member chamber and three-tier suffrage based on the example of the Union parliament in September 1850. There was no parliamentary consultation on the new electoral law because the duke dissolved parliament on April 2, 1851. On November 25, Adolph finally enacted the new electoral law by ordinance, which provided for a two-chamber system similar to that before 1848. There were hardly any attempts to campaign on the part of political groups and the few remaining associations. On February 14 and 16, 1852, the highest taxed landowners and tradesmen, together less than a hundred people in the entire duchy, elected their six members of the first chamber. The electors were elected on February 9th. They, in turn, elected the deputies of the second chamber on February 18. For the election of 1852, the number of eligible voters can be determined to be 70,490 for the first time. The turnout was three to four percent. In some communities it did not take place at all due to a lack of interest. In contrast to previous parliaments, farmers made up the largest group among the members of the second chamber.

There were bitter domestic political disputes again in 1864, when the government intended to sell the Marienstatt Abbey in the Westerwald. The complex was secularized in 1803 and then passed into private ownership. In 1841 the facility was for sale and the government drafted plans to acquire the abbey building and convert it into the first state home for old and poor residents on Nassau soil. The state master builder estimated the cost of repairing and converting the former abbey to be 34,000 guilders. In 1842 the duchy bought the property for 19,500 guilders. Shortly afterwards it turned out that the buildings were in too bad a condition for the project. Marienstatt continued to fall into disrepair until the 1860s. During this time the diocese of Limburg began to be interested in the acquisition. It wanted to set up a home for neglected children there. The government was also interested in the sale to get rid of the running costs of the idle complex. The former abbey changed hands on May 18, 1864 for 20,900 guilders. Shortly before, in the election on November 25, 1863, the Liberals had achieved a large majority in the second chamber of parliament. The electoral program set up demanded, among other things, that the privileges that had been granted to the Catholic Church should also apply to other religious communities. On June 9, 1864, the Liberals moved to the assembly of estates that the sale should not be carried out. They argued that buildings and the property belonging to them were far more valuable than the proceeds from the auction and that the assembly of stalls had a say in the sale of state property to a large extent. The latter denied the government representatives and emphasized the social purpose of the facility, which should be rated higher than any possible commercial use. In the further course of the debate, which lasted several sessions, there were also arguments between pro and anti-clerical MPs. The latter generally disapproved of the fact that the Catholic Church should be allowed to supervise children. Ultimately, the sale was not reversed despite the parliamentary dispute.

End and aftermath

In the German War of 1866, the Duchy of Nassau stood on the side of Austria , even though there had been considerable resistance to mobilization against Prussia within the population and especially in liberal and entrepreneurial circles. After the war had already been lost in the Battle of Königgrätz , Nassau's “victory” over Prussia on July 12, 1866 in the “ Battle of Zorn ”, a minor skirmish near Wiesbaden , could not prevent its subsequent annexation by Prussia .

Even before the conclusion of the Peace of Prague on August 23, 1866 and two days before the creation of the North German Confederation, the king announced on August 16, 1866 to both houses of the Prussian state parliament the intention to open Hanover, Hessen-Kassel, Nassau and the city of Frankfurt am Main always to unite with the Prussian monarchy. Both houses were asked to give their constitutional approval. The corresponding bill stipulated that the Prussian constitution should come into force on October 1, 1867 in the countries mentioned. The law on the expansion of the Prussian state territory, which was adopted by both houses of the Prussian state parliament, received sovereign enforcement on September 20, 1866 and was published in the collection of laws. Next step was the publication of possession Seizure patents by which the King welcomed the members of the new parts of the country as new citizens of the Prussian state. After these solemn events, orders were gradually made to regulate the administration of the new parts of the country temporarily until they had fully entered the Prussian state body.

In the politically active public in Nassau, the annexation was accepted rather with approval. The Nassau Progressive Party, as the most important organization of the liberals in the country, criticized Bismarck's actions against the liberal opposition in Prussia in previous years, but was basically a little German and had opposed the entry into the war against Prussia. The economic dependence of Nassau on Prussia was an important argument. In a petition dated July 31, 1866, around 50 liberal politicians and industrialists called for the "unconditional and unconditional incorporation" of Nassau into Prussia. On the part of the common population there were hardly any comments about the change of rule. Displeasure only arose because of the higher Prussian taxes and duties that would soon apply, as well as the changeover to new legal regulations, while on the other hand Prussian administrative officials wanted to retain some of Nassau's still feudal regulations, for example in hunting law.

Nassau went up in 1868 with the also annexed states of the Free City of Frankfurt and the Electorate of Hesse in the newly created Prussian province of Hesse-Nassau . The provincial capital was the former residence of the Electorate of Hesse, Kassel . Nassau and Frankfurt formed the Wiesbaden administrative region .

In 1945, the greater part of the former Nassau belonged to the American occupation zone and became part of the state of Hesse . There this part of the country continued as the Wiesbaden administrative district until 1968, when it was assigned to the Darmstadt administrative district .

The rest came to the French occupation zone and subsequently formed the administrative district of Montabaur in Rhineland-Palatinate . In 1956, a referendum to join Hesse took place, but it was rejected.

Politics of the Duchy

Foreign policy

In terms of foreign policy, the duchy's leeway was always limited due to its small size and economic weakness; it did not exist in the Napoleonic era. In November 1813 Nassau switched to the side of the anti-Napoleonic allies. After the Congress of Vienna in 1815 , Nassau became a member of the German Confederation .

On the German question , the duchy took an ambivalent position. The country's low export economy was geared towards North German, especially Prussian, customers. As a rule, however, the dukes and leading government officials took a Greater German, Austria-friendly attitude. This dichotomy was evident, among other things, in the long controversial accession to the small German German Customs Union . In the late phase of the duchy, the Nassau Progressive Party, as the most important liberal force, was small-German.

Military policy

The Nassau military policy resulted from the respective alliance obligations of the duchy. Like the rest of the administration, the military came into being through the merging of units from the predecessor states, which were reformed into a single military.

In the early phase of the duchy, military contingents from his Napoleon were deployed at will, first in 1806 as occupation troops in Berlin , then three battalions during the siege of Kolberg in 1807 , two regiments of infantry and two squadrons of cavalry fought for Napoleon in Spain for more than five years - only half came back. The bulk of the troops were two regiments of infantry, formed in 1808/09. These were supported by squadrons of mounted hunters during the Napoleonic Wars .

After the Battle of Waterloo , the Duchy provided a artillery - company , from 1833 Artillery Division to two companies, on. In addition, there were other smaller units ( pioneers , hunters, baggage train , reserve ). In the event of war, additional associations were set up as required. The Nassau military was grouped under one brigade command. At its head stood the Duke, the daily orders were issued by the respective adjutant general . The regular strength of the Nassau army was about 4,000 soldiers.

After the end of the duchy, numerous officers and soldiers switched to the Prussian army .

Educational policy

Because the duchy could not afford a university of its own, Duke Wilhelm I signed a state treaty with the Kingdom of Hanover that allowed Nassauern to study at the University of Göttingen . To finance schools and university scholarships, he founded the Nassau Central Study Fund, which still exists today, on March 29, 1817 by amalgamating older secular and spiritual foundations, with share capital from farmland, forests and securities.

In Göttingen, non-Nassau students are said to have occasionally sneaked a free table financed by the Central Study Fund . This is why the expression " wet whistle " should come from: obtaining unjustified privileges / advantages. The linguistics derives originally Berlinische but word from the Yiddish - Rotwelschen , and sees the free table narrative retrospective etiology .

Religious politics

The merger of the two predecessor territories and the secularization and mediatization resulted in a confessionally inconsistent state. The religious division was in 1820: 53 percent Protestant-Union, 45 percent Catholic, 1.7 percent Jewish and 0.06 percent Mennonite. Mixed denominational settlements were the exception. Most of the towns and cities were clearly dominated by one of the two major Christian denominations. The Jewish population was spread over the entire duchy, with a focus on the Lahn and Main.

As is customary in Protestant territories, the constitution placed the church under state administration. The Evangelical Lutheran and Evangelical Reformed churches were the first Protestant churches in the German Confederation to merge in 1817 in what was then the "City Church" of Idstein to form the United Evangelical Church in Nassau (Nassau Union).

As early as 1804 there were first attempts to create a Catholic state diocese for Nassau. But it was not until 1821 that the Duchy and the Holy See agreed on the establishment of the Limburg diocese , which was completed in 1827.

In addition to direct church politics, there were other points of contact between state politics and church action. When a religious community, the Redemptorist Order , first settled in Bornhofen , there was a test of strength between the state and the bishop. This ended with the community remaining in place. The growing religious communities in the duchy gave rise to political disputes on several occasions. The community of poor servants of Jesus Christ , founded in Dernbach in the Westerwald in 1845 , was tolerated by the state, if not supported in silence, because of its work in nursing after initial problems and nonsense that flickered again and again at a low level. This is how 'hospitals' or outpatient care stations emerged in many places, the forerunners of today's social stations.

Press

The Duchy of Nassau had a poorly developed press landscape, which is due to the low number of educated citizens and the press and censorship laws. With the exception of the founding phase and the short period of the reform constitution, the Nassau press law was as strict as in most other German states. From 1814 only the "Vaterländische Chronik" appeared in Langenschwalbach and the "Rheinische Blätter" in Wiesbaden. Both were reinstated after the Karlsbad resolutions in 1819. Until 1848, only official and entertainment papers appeared within the country. However, some newspapers from neighboring countries also dealt with issues of Nassau politics and were allowed to be sold in the duchy. The Frankfurt newspapers were particularly popular in the south of the duchy.

A surge in the start-up of new newspapers went hand in hand with the freedom of the press in 1848. The "Freie Zeitung" appeared in Wiesbaden in March 1848 and by April had 2,100 subscribers. She initially adopted a moderately liberal stance and was the mouthpiece of the Hergenhahn group. Later, the "Freie Zeitung" became increasingly radical, advocating revolutionary and anti-Catholic theses. The spectrum of moderate liberalism was increasingly covered by the “Nassauische Allgemeine Zeitung”, first published in Wiesbaden on April 1, 1848, with editor-in-chief Wilhelm Heinrich Riehl . Another moderately liberal paper that addressed a small, educated middle class readership was the "Nassauische Zeitung" with the young Karl Braun as editor. Among the many local newspapers of that time, only the “Lahnbote” from Weilburg and the “Deutsch-Nassauische Volksblatt” from Dillenburg printed political contributions. In the course of 1849 and until the spring of 1850, the newspapers largely ceased political reporting under pressure from the government. From 1851 on, the Nassauische Landeszeitung came increasingly under the influence of the ducal government. She mainly published administrative announcements and contributions with government positions and received public advertisements and official subscriptions.

From 1864 to 1866 the "Nassauische Landeszeitung" appeared in Wiesbaden as the mouthpiece of the ducal government and the "Mittelrheinische Zeitung", which was close to the liberal opposition and later to the Prussian-friendly Nassau Progressive Party. The “Neue Mittelrheinische Zeitung” appeared for the first time in 1866 as a counterpart to the Greater Germany and Austria. Only the “Aarbote”, which appeared in Langenschwalbach, had a political claim. There were also around two dozen local and advertising papers.

Club life

The 19th century was an era when the association was founded in the Duchy of Nassau. Many of the nationwide non-political associations were favored by the government and entrusted with state tasks. Members of the ducal family were often members of the association. Political associations in Nassau have been banned and prosecuted since the Karlsbad resolutions in 1819 at the latest . These included in particular the gymnastics clubs, the establishment of which was permitted again in 1842. In the course of the March Revolution, freedom of association and assembly was granted on March 4, 1848. With the collapse of the revolution in 1850, membership began to decline, particularly in the political but also in many other associations. Formally, the relevant freedoms were largely repealed with the Law on Associations and Assemblies of December 13, 1851. Associations could only be brought into being within the framework of a previously approved public meeting and with the consent of the government authorities. In addition, it was forbidden to make contact with other associations or to membership of students, apprentices and women. Membership lists and statutes had to be handed over to the local police. The remaining workers', gymnastics and political clubs dissolved by the end of 1852.

The German societies in Idstein and Wiesbaden, which met in the spirit of Ernst Moritz Arndt , were among the first Nassau associations . After the government ban, the clubs disbanded. The Wiesbadener Verein was converted into the casino company, which pursued the apolitical purpose of "social entertainment". The casino company was a driving force behind the founding of the learned and sociable associations.

With the Society for Nassau Antiquities and Historical Research, one of today's oldest German historical societies was founded in 1812. The association was given the task of state archeology and monument preservation . As a result, the association put on a collection of Nassau antiquities. This collection formed the basis of the Wiesbaden Museum , which the association set up in accordance with the statutes in 1825. When the museum was founded, it already had the following structure: history, art and nature. The Society for Natural History in the Duchy of Nassau (1829) and the Society of Friends of Fine Arts in the Duchy of Nassau (1847) were founded to look after the collections .

In addition to the learned and sociable associations, national business associations were established. The oldest was the Agricultural Association in the Duchy of Nassau . This was brought into being by the government in 1818 to take over the sponsorship of the new Idstein agricultural school. In 1841 the trade association for the Duchy of Nassau was founded. Since the trade association was a private institution, the government tried to maintain control of this association. It was not until 1844 that the association's statutes were approved. By 1866 it had grown to 35 local groups and around 2000 members. In 1845 the first trade school was founded in Wiesbaden. In 1866 there were 35 in the entire duchy, mostly with evening classes in other schools. They were owned by the trade associations, but were mainly financed by the state. The trade association organized trade exhibitions in Wiesbaden in 1846, 1850 and 1863. In 1864/65 chambers of commerce were formed in Wiesbaden, Limburg and Dillenburg.

In addition, many local associations were founded. In particular, it was about singing, gymnastics and sports clubs. The gymnastics clubs in particular, but also the majority of the choral societies, were nationally oriented. While sports clubs remained primarily an urban phenomenon, numerous choral societies were founded in the countryside right down to the small villages, often initiated by the village school teachers. In 1844 the Nassau, Hessen-Darmstadt and Prussian singers' associations merged to form the Lahntalsängerbund. The urban and, in some cases, rural reading associations existed with different focuses, especially denominational, but also nationally oriented, but expressly supporting the state.

In the context of the revolution of 1848, trade, agricultural, women's, beautification and fire brigade associations emerged at the local level . Above all, however, new political, often democratically oriented, associations were founded in the course of the revolution. In the course of the revolution, several of the older education and reading associations dissolved and were replaced by new, more politically oriented successors.

On July 27, 1872, the fire brigades merged in Wiesbaden to form the fire brigade association for the Wiesbaden district , which continues to operate as the Hessian district fire brigade association under the name " Nassauischer Feuerwehrverband ".

economy

The economic situation of the small duchy was precarious. The largest part of the national territory was occupied by agriculturally inferior locations in the low mountain ranges, which also represented a considerable impairment in inland traffic. More than a third of the working population worked on their own farm, almost exclusively family businesses with a small area, which was split up by the division of inheritance . The majority of these smallholders were dependent on a sideline, in the Westerwald often on additional income as peddlers . Larger goods were rare exceptions. The overwhelming majority of the traders were craftsmen.

Currency and coins

The duchy belonged to the southern German currency area. The most important coin unit was accordingly the guilder . This was minted as Kurant coins . Up to 1837, 24 guilders were minted from the Cologne mark of fine silver (233.856 grams ). The guilder was divided into 60 cruisers . Divisional coins made of silver and copper were minted at 6 (not until 1816), 3, 1, 0.5 and 0.25 Kreuzer.

From 1816 the Kronentaler was minted at 162 kreuzers, equivalent to 2.7 guilders. From 1837 the duchy belonged to the contracting states of the Munich Mint Treaty , which stipulated the minting of 24.5 guilders from one silver mark (233.855 grams). After the conclusion of the Dresden Mint Agreement in 1838, thalers were also recognized as Kurant coins and minted in small quantities. Two thalers corresponded to 3 ½ guilders. In 1842 the Heller was still minted to a quarter cruiser as the smallest copper coin. In 1820 the Heller was the smallest contribution size, alongside the guilder and the cruiser. B. for property and trade tax. According to the Vienna Mint Treaty , the duchy minted club thalers in addition to guilders . One pound (500 grams) of silver was used to mint 52 ½ guilders or 30 thalers. Instead of the Heller, pfennigs were given out to a quarter cruiser. The Vereinstaler remained in circulation until 1908.

Banknotes, so-called Landes-Credit-Casse-Scheine, were issued from 1840 by the Landes-Credit-Casse , Wiesbaden. They were in circulation in face values of one, five, ten and 25 guilders.

The Nassau predecessor states had not minted any new coins since 1753, so that when the duchy was founded, many old, worn coins were in circulation. In 1807 the dukes decided to issue a new coin. Nassau recruited Christian Teichmann, a mint master from Berg, for this purpose. He was active in the former Electorate of Trier mint in Ehrenbreitstein and produced copper, silver and gold coins. The first coinage to cover immediate needs took place in Hesse-Darmstadt in 1808 for Nassau's account. The first coins from Ehrenbreitstein were not issued until 1809. In 1815 the mint had to be relocated to Limburg in the former Franciscan monastery and today's episcopal ordinariate, as Ehrenbreitstein fell to Prussia. In 1830 it was relocated again to Luisenplatz in Wiesbaden.

Business statistics

The State Statistical Handbook of 1819 lists a total of 26,038 arable and 790 wine growers among 64,825 traders (mainly in the Rheingau, but also elsewhere on the Rhine, Main and Lahn). More than 24,000 of these farmers only had a single team of draft animals. In addition, numerous smallholders who had to earn additional income from other trades were registered as craftsmen or small traders among the 18,319 day laborers. Most of the winegrowers were family businesses without employees. Statistics from 1846 show only 500 manufacturers and executives among the 25,600 traders. In 1819, 2225 innkeepers and 1833 traders were also statistically recorded. Since in 1388 the traders were classified in the three lowest tax brackets, they must have been small shopkeepers. Among the craftsmen, the State Handbook lists 6083 members of the textile, leather and clothing industry and 3199 traders in the food and beverage industry. Wood processing followed with 1785, mining and metal processing with 1604 and construction with 1312 companies. 4,000 civil servants and officers, including 750 teachers, 350 pastors and 1,600 part-time mayors and community calculators complete the statistics from 1819.

Iron mining and production

Only on the Lahn were there early industrial approaches, especially in the mining and smelting of iron ore. In 1828 almost 760,000 quintals of Roteisenstein were mined, in 1864 a little more than 6.5 million quintals. The development between these dates is characterized by strong fluctuations. From 1858 to 1860, production fell by almost half to around 2.6 million tons. The production of Brauneisenstein rose from 496 quintals in 1828 to around 546,000 quintals in 1854, only to decline thereafter. Within the German Confederation, the Duchy, alternating with the Kingdom of Bavaria, recorded the second highest pig iron production after Prussia.

However, it was never possible to build up an industry on a large scale that processed the iron into higher-quality products. The companies were small and mostly organized in a craft rather than an industrial manner. They relied exclusively on charcoal as fuel, the production of which could hardly be expanded without permanently damaging the forest. In 1847 there was only one ironworks with more than 200 employees. As a rule, companies from the Ruhr area opened branches on the Lahn and had the iron transported to the main locations for further processing, where there was enough hard coal that was not available on the Lahn. Iron ore mining and processing played a prominent role in the comparatively small state. From 1848 to 1857, almost 4,500 people were employed in this branch in Nassau, around one percent of the population. This was the highest percentage in the German Confederation. The Duchy of Braunschweig had the next lower quota at 0.5 percent. However, the number of workers in ore mining and processing fluctuated considerably according to demand and the production it determined.

See also: Lahn-Dill area

The iron and steel industry in Nassau developed slowly until 1850. In 1828 256 employees produced around 207,000 quintals of pig iron and 31,000 quintals of cast iron. In the years that followed, these numbers were tended to fall short of than exceeded. From the middle of the century, an increase began, which led to 472,000 quintals of pig iron and 118,000 quintals of cast goods with more than 900 employees in 1864. The iron, sheet metal and wire production remained consistently low and seems to have exclusively served the domestic market.

Other natural resources

The mining of lead and silver ores was substantial, albeit volatile. The minimum was reached in 1840 with a good 30,000 hundredweight, the maximum in 1864 with a good 133,000 hundredweight. By far the largest part of this production was smelted within the country. Up to 2350 people (1860) worked in lead and silver mining. The largest silver mine with around 300 employees was located at Holzappel around 1820. Zinc mining reached its peak in 1850 with almost 19,000 hundredweight. This ore was exported in full, while the likewise low copper yield (maximum in 1864 with just under 12,000 quintals) remained almost entirely in the country. The mining of nickel (1862: 22,000 quintals) and heavy spar (1854: 39,000 quintals) remained marginal .

Lignite was mined to a small extent in the Westerwald lignite area . Up to four fifths of the production was burned domestically. Production was just under 34,000 quintals in 1828 and just over a million quintals in 1864. The number of employees reached its maximum in 1858 with almost 1,000. The increase in production with a smaller number of employees can be explained by the increased use of technology and more easily accessible deposits.

The roof slate quarries of the duchy produced between 10,000 (1828) and 38,000 quintals (1862) of the material. By 1840, the number of employees was slightly above 1100. Immediately an der Lahn, especially in the countryside around Runkel was marble broken.

Clay minerals were also mined in the Westerwald and up to three quarters were processed in the pottery industry within the duchy. In 1828 the production was just under 95,000 quintals, in 1864 around 440,000 quintals. The employment maximum was reached in 1862 with 262 workers in clay mining.

The industrial additive fulling earth with up to 8,700 quintals was also mined to a small extent in 1856.

Economic policy

Agriculture and Forestry

Immediately after its founding, the principality's economic policy concentrated on the dominant branch of the economy: agriculture and forestry. The Gassenbach farm near Idstein was built into an agricultural model farm in 1812 , based on the model of Gut Hofwil in Switzerland. There, new production techniques should be tried out and propagated among the farmers, in particular a modern crop rotation as a further development of the three-field economy . In 1818 an agricultural institute was set up in Idstein, the first in western Germany. 10 to 20 young farmers were initially trained in modern farming methods in two-year courses. In 1835 the institute was relocated to Hof Geisberg near Wiesbaden. In 1820 the government founded the "Agricultural Association in the Duchy of Nassau". Annual animal awards, yearbooks and, in particular, the “Landwirtschaftliche Wochenblatt” contributed to the dissemination of new, scientific methods in agriculture.

An undisputed obstacle to the development of agriculture in Nassau was the fragmentation of farms and individual usable areas through the real division . Decrees to limit the real division had already existed in the predecessor territories from the late 16th century and almost everywhere in the 18th century. However, they had little effect, among other things because the village communities orally passed down inheritance divisions and even without public and legally valid documentation of property divisions, the land was cultivated in divided areas. On the other hand, there was also occasional consolidation in response to community or local initiatives. After Ibell's efforts in the early phase of the duchy got stuck in the design phase, the duke issued an ordinance on the consolidation of goods on September 12, 1829 . Detailed instructions followed in 1830, stipulating half an acre (1,250 square meters) for arable land and a quarter acre (625 square meters) as "normal parcel" and thus the minimum size for a single piece of land. The procedure envisaged co-determination of the landowners through a majority vote both when initiating the consolidation and when choosing the geometer involved and the appraisers who had to determine the value of the land. Likewise, proposals for amalgamation and technical improvement of the agricultural areas (drainage, construction of roads, stream regulation, etc.) were passed by majority vote. The great importance of land improvement differentiated the Nassau approach from the Prussian approach, for example. Disputes and unclear ownership should be resolved by the respective office. At the end of the process, the parcels were allocated by lot.

In 1840 the tithe replacement began in Nassau after many German states had already taken this step. The replacement, however, made slow progress. Therefore the tenth question remained an important problem during the revolution of 1848 and was a reason for the particularly high mobilization of the rural population in Nassau. It finally managed to enforce a uniform transfer fee, 16 times the decade, of which the state treasury took one eighth. However, the amount of the transfer fee led to the massive indebtedness of the farmers, especially with the Landes-Credit-Casse , to which they now had to pay interest instead of tithing.

With a forest share of 41 percent, the duchy was one of the most forested states in the German Confederation. About three quarters of the forest belonged to the municipalities, a fifth to the ducal domain and only five percent were private forests. At the beginning of the 19th century, the forests were damaged by excessive use. Nevertheless, the revenues from the forest were one of the most important sources of income for the municipalities. After the territorial additions in 1803 and 1806, the forestry was completely fragmented. In the new federal states, the form of organization was mostly completely different compared to the two parts of the old Nassau region. In 1808 there were first considerations for a new forest organization. But it was not until November 9, 1816, that the edict of forest organization was published at the same time as the instructions for forest personnel and the Forest, Hunting and Fishing Regulations Act. The forest organization edict was groundbreaking for all other forest organizations in Germany. For the first time, the scientifically trained head forester was required, who combined planning and execution in one hand. This laid the foundation for modern forestry. A student of the forest classic Georg Ludwig Hartig , Johann Justus Klein from Dillenburg, is considered to be the creator of the organizational edict. In cooperation with the District President Carl Friedrich Emil von Ibell , a law was created that lasted in Hesse until 1955 and in Rhineland-Palatinate until 1950. Today's forest organization builds on the Nassau.

Metallurgy

Political interventions in the metallurgy were limited to the supervision of the mountain order by officials. This also extended to a certain control of wages and from 1861 also to a supervision of the miners' insurance.

Trade policy

In 1819 the Nassau government repealed the guild constitution . Anyone wishing to open a business only had to report this to the local authorities, who were only allowed to give permission in exceptional cases. In the years that followed, this led to a decline in the number of masters and trained journeymen. In the revolution of 1848 they enforced that only holders of the master's title were allowed to practice a trade independently. In 1860, however, the duchy returned to complete freedom of trade. At the same time, many craft businesses had been largely displaced by industrial production.

In 1844 trade associations were formed on a private initiative. Chambers of Commerce were founded relatively late in 1863.

Trade policy

In 1815 all internal tariffs within the duchy were abolished and external tariffs were waived. The ducal government also pursued an express free trade policy externally. The Prussian customs system introduced in 1818, however, severely affected Nassau trade. In particular, the export of agricultural goods to Prussia collapsed. Efforts to reach a bilateral trade agreement with Prussia were unsuccessful. In 1822, Nassau finally introduced border tariffs to improve state finances and protect its own companies from competition. The increase in income succeeded, but complaints from traders and producers, whose export business was hampered by the tariffs, increased in the following years.

In 1828 Nassau joined the Central German Trade Association sponsored by Austria . In the years that followed, there was increased smuggling into other Prussian countries, petitions to join the Prussian- dominated German Customs Union, and sometimes violent protests by farmers and winegrowers. After Prussia had weakened the trade association through several bilateral agreements with individual members and Minister of State Marschall von Bieberstein died in 1834 as a strong advocate of customs independence from Prussia, Nassau joined the German Customs Union on January 1, 1836. The duchy had enforced the continued existence of its own customs administration, its own voice in the customs union conference and special regulations for its own customs on the Rhine and Main. The positive consequences for the Nassau economy remained manageable and mainly concerned the export of cattle.

Within the Zollverein, Nassau campaigned in particular for the collection and receipt of duties on the import of iron in order to protect its own iron and steel industry. The share of customs duties in the total income of the duchy rose from 12 percent in 1833 to 26.4% in 1846.

The termination of the customs union agreements by Prussia in 1851 with effect from the end of 1853 was received with indignation in the Nassau government. Because of the close trade ties with Prussia, negotiations with Austria about an alternative tariff alliance remained unsuccessful, but sparked fierce resistance, especially among the Nassau industrialists and winegrowers. A similar crisis occurred in 1862 after the conclusion of a Franco-Prussian trade agreement, which ran counter to some agreements within the German Customs Union and with Austria. Again there was a considerable mobilization within Nassau in favor of Prussia and against the pro-Austrian government and the duke.

Transport policy

The transport links to the industrial sites, including that of the Prussian Wetzlar , were supposed to be improved by expanding the Lahn into a waterway, but this was only achieved slowly and incompletely. In its section of the Rhine , the Nassau government had obstacles removed, for example at Bingen , Bacharach and Oberwesel . At the Congress of Vienna, Nassau and the Grand Duchy of Baden vigorously opposed joint administration of the Rhine by the neighboring states. When the Rhine Commission in 1816 but met, blocked Nassau now on the abolition of the Rhine customs duties , which accounted for a significant share of its budget revenues. They were also preserved when the Mannheim Act in 1831 abolished numerous traditional trade privileges.

railroad

The projects to expand the Rhine and Lahn had hardly been completed when the railway announced itself . The Nassau government was therefore unwilling to invest in this new infrastructure, and initially left this field to private capital. In addition, there were disputes with Prussia, which in addition to the existing railway line on the left bank of the Rhine wanted another in the hinterland on the right bank of the Rhine, which would not have been interrupted so quickly by opposing advances in the event of a war with France. Nassau, on the other hand, advocated a line directly on the right bank of the Rhine.

1840 reached from Frankfurt coming Taunus Railway Wiesbaden. A private company has now been founded there that wanted to continue the railway along the Rhine. This initially operated as the Wiesbadener Eisenbahngesellschaft , from 1853 as the Nassauische Rhein Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft , after 1855 as the Nassauische Rhein- und Lahn Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft . On June 23, 1853, the company received the concession to build the Nassau Rhine Valley Railway Wiesbaden - Rüdesheim - Oberlahnstein . On March 31, 1857, the concession for the Lahntalbahn from Oberlahnstein to Wetzlar followed . In the absence of sufficient financial resources for the company, however, only parts of the total of 188 kilometers of licensed routes were completed. So the duchy finally withdrew the concessions from the company and took over the existing railway lines with a contract of May 2, 1861, continued to operate them as the " Nassau State Railway " and completed them. This also met the Prussian wish for a railway connection in the east Rhenish hinterland. Prussia bought this concession from Nassau with the Pfaffendorfer Bridge near Koblenz , which connected the Nassau railway network to the line on the left bank of the Rhine. In 1852 there were also drafts for a direct rail connection between the iron ore district around Wetzlar and the Ruhr area via the Sieg and Dill regions. However, they never got beyond draft status.

Emigration from Nassau

From 1817 on, a second wave of emigration from the German countries to America began, which also affected Nassau. The reasons were economic hardship, among other things as a result of the year without a summer and the high tax burden from the coalition wars , the political restrictions of the Restoration era and the legal relief of emigration in many territories. The impetus was given by the mass emigration of the spring of 1817, during which many emigrants from Switzerland and southwest Germany moved along the Rhine to the Dutch ports. This resulted in many contacts with the Nassau population, which motivated many residents to emigrate, especially in the traditionally distressed Westerwald.