Eberbach Monastery

| Eberbach Cistercian Abbey | |

|---|---|

Eberbach Monastery 2006 |

|

| location |

Germany Hessen |

| Lies in the diocese | former Archdiocese of Mainz , today Diocese of Limburg |

| Coordinates: | 50 ° 2 '33 " N , 8 ° 2' 48" E |

| Serial number according to Janauschek |

48 |

| Patronage |

Maria Immaculata John the Baptist |

| founding year | 1136 |

| Year of dissolution / annulment |

1803 |

| Mother monastery | Clairvaux Monastery |

|

Daughter monasteries |

Schönau Monastery (1142) |

The Kloster Eberbach (also Monastery Erbach ; lat. Abbatia Eberbacensis ) is a former Cistercian abbey near Eltville in the Rheingau , Hesse . The monastery, famous for its viticulture, was one of the oldest and most important Cistercians in Germany. The complex, located in the Rhine-Taunus Nature Park , with its Romanesque and early Gothic buildings is one of the most important art monuments in Europe .

history

Foundation and advancement (12th / 13th century)

The founding of the Cistercian monastery in Eberbach goes back to Bernhard von Clairvaux . After the founding of the Himmerod monastery in the Eifel , the Clairvaux monastery of the Cistercian order tried to establish another subsidiary in Germany. On February 13, 1136, the Eberbach Monastery was founded by Abbot Ruthard and 12 monks who were sent from Clairvaux. The monastery was under the patronage of Maria Immaculata and under the patronage of John the Baptist . This establishment of the Clairvaux Primary Abbey was unusual, as all other Cistercian monasteries in Germany were founded by the Burgundian Primary Abbey of Morimond .

The foundation of the Eberbach Monastery was an Augustinian Canons Foundation founded in 1116 by Mainz Bishop Adalbert I of Saarbrücken . The patron saint of this pen was St. Thomas . However, the monastery was driven out of there by Adalbert because of alleged indecency in 1131 and relocated to St. Aegidius in Mittelheim . The buildings of the monastery were used temporarily for a priory of the Johannisberg monastery . The Cistercians were able to move into the abandoned buildings and build a new monastery based on Cistercian ideals.

The Eberbach monastery developed quickly. The subsidiary Schönau in the Odenwald was founded as early as 1142 . At this time, according to the statutes of the Cistercians, the Eberbach monastery had to have more than 60 monks. In the following years the daughter monastery Otterberg in Palatinate was founded in 1144/45 and the daughter monastery Hocht , later Gottesthal (Val-Dieu) near Liège, was founded in 1155 .

Eberbach experienced a first crisis during the split in the church between 1160 and 1170. The Cistercian order supported Pope Alexander III. against the popes of the Hohenstaufen emperor Friedrich Barbarossa . Like the Archbishop of Mainz Konrad I von Wittelsbach , the Eberbach abbot fled to Rome. Other monks temporarily fled to France. However, they returned to the emerging monastery after a few years.

In 1174 the subsidiary Arnsburg monastery was founded in Wetterau .

A daughter monastery planned by Eberbach and his daughter monastery Schönau in the early 13th century in the Kingdom of Sicily could not be founded. The planning took place under Abbot Theobald, who was already abbot of the Schönau monastery before his Eberbach Abbatiat. The planning was before the general chapter. The abbots of Casamari and Fossanova were commissioned to check the implementation. However, in 1217 several monks moved to the Sambucina Monastery , a daughter monastery of Casamari.

Archbishop Siegfried III occupied from 1232 to 1234 . from Eppstein the Lorsch monastery with monks from Eberbach. The previous Benedictine monastery was to be reformed according to the rules of the Cistercians. After the Reformation did not bring the desired result, the Lorsch Monastery was handed over to the Premonstratensians . During the period of occupation, 35 Carolingian manuscripts were brought to the library of the Eberbach monastery.

Another planned foundation of a monastery in the Hanau Forest around 1234 foiled the Counts of Hanau .

Social composition

As a Cistercian monastery, Eberbach followed the rules of the Cistercian Reformation. This demanded a monastery life strictly based on the Benedictine rules. The monks should live on the labor of their own hands. This work requirement made monastic life in Eberbach unattractive for nobles , so that the monks came from non-aristocratic classes throughout the history of the monastery. From the need to organize work and prayer, the Cistercians separated into different classes . The highest were the monks / priests ( manuum / oratores ). These were studied theologians . Among them were the Konversen / lay brothers ( conversi / illitterati ) as co-workers who lived monk. Monks and conversations lived in separate rooms and had separate places in the basilica. A change from the status of the conversant to the monk status was not possible. Only estimates of the size of the convent are available for the Middle Ages . The convent therefore comprised around 300 people, including 100 monks and 200 converses. Similar conditions can also be observed in other Cistercian monasteries. The high proportion of conversations formed the basis of the rapid expansion of the order. The lowest class was formed by the wage laborers ( mercenarii ) who were temporarily recruited, for example as harvest workers .

In the Middle Ages, most of the conversations came from farming families. The conversations only took part in the spiritual life in the monastery to a limited extent. They were forbidden to do mental activities such as reading books. In the election of the abbot they had no right to vote. In the 12th century, the position of a converse was still coveted, as the monastery community offered better living conditions than working as a simple farmer or wage worker. Many Konversen lived in whole or in part on the grangia and not directly in the monastery.

Monastery economy

As a result of the command to live from one's own work, the monastery strictly rejected the leasing of land and income from feudal rights in the first few centuries. Parishes were also not taken over initially.

Instead, an extensive network of self-managed farms, the so-called Grangien, formed the basis of the monastery economy. For the year 1163, twelve grangia are already recorded, including the Draiser Hof , Hof Reichartshausen and the Neuhof near the monastery , four more were laid out in the 12th century. They were used to grow grain and raise livestock. In the early phase of the monastery, only a small part of the agricultural land was used for wine-growing. The range of the possessions becomes clear , for example, at the Grangie Hadamar . This was built on the basis of several donations between 1190 and 1230 in the village 50 kilometers from the monastery. There is evidence that at least six converses lived and worked on the farm, plus seasonal wage laborers. The construction of the St. Wendelin Bridge near the courtyard is attributed to the monks of the monastery. The farm was sold in 1320 to Count Emich I of Nassau-Hadamar , who expanded it into Hadamar Castle . From then on, the monastery managed its property in this region from the Erbacher Hof in Limburg . In Limburg, the street name Erbach , a variant of the monastery name Eberbach, still reminds of the monastery courtyard there.

In addition, the monastery maintained eleven city courtyards , including the Eberbacher Hof in Cologne , Frankfurt and the Erbacher Hof in Mainz , which served as workshops, trading posts and hostels. The Cologne court and its wine cellar were in a 1162 issued for Eberbach privilege of Pope Alexander III. first mentioned. The court was the destination of the monastery’s annual Cologne trip , the central event of the financial year. As part of the trip, the annual surplus wine production was shipped to Cologne in order to sell it on the market. The Cologne court developed into an important trading post for the monastery, as the Hanseatic city of Cologne was the center of the northern European wine trade. The abbot of the monastery was regularly responsible for directing the trip. If the water level was suitable, the trip took place in autumn, otherwise in spring. During the journey, crops were collected from the downstream farms. The proceeds were used to purchase higher quality goods that the monastery could not produce itself.

In the 13th century, the monastery also had farms in Boppard . Since these were very cramped, it moved to a new farm in Boppard's Niederstadt by 1323 at the latest, which became a large administrative center for the important possessions on the Middle Rhine. The Ebertor still bears witness to this farm today .

Spiritual development

Although the Cistercians were not a scientific order, the Eberbach monastery produced some notable theologians and scholars in the Middle Ages .

Abbot Konrad , who died in 1221, came from the mother monastery of Clairvaux. He was the author of the Exordium magnum Cisterciense , an important work on the early history of the Cistercian order.

The simultaneously incumbent Prior Gibo acted as a mediator of the writings of St. Hildegard , the master of the nearby Rupertsberg monastery near Bingen . The work Speculum futurorum temporum, sive "Pentachronon" sanctae Hildegardis , compiled by Gibo, is considered to have paved the way for Hildegard's popularity. The master, recognized by her contemporaries as a prophetess, was in lively exchange with the Eberbach monastery. In the introduction to the work, Lasseno refers to the visit of Abbot Johannes of the Sambucina monastery in Eberbach in 1217 and his discussion of the eschatological work of Joachim von Fiore . Like Bernhard von Clairvaux, Joachim is expressly named as a prophet who, like Hildegard, is equal to the eagle of John (as the author of the Revelation of John ).

Abbot Jakob from Eltville, a professor of the Paris Sorbonne, was elected abbot in 1372 . He is considered to be the author of important theological works.

Popular piety also flourished around the monastery. When Bernhard von Clairvaux founded the monastery, miracles are said to have occurred. The water of the Kisselbach is said to have suddenly flowed uphill or a boar staked out the construction site. The gift of miraculous healing by the laying on of hands was also attributed to several Eberbacher conversations in contemporary sources from the 12th century .

The monastery acquired a considerable collection of relics over the centuries . The jaw of St. Bernard was kept in Eberbach. The head reliquary of St. Valentius from the Kiedrich pilgrimage church came from the Eberbach reliquary collection. When the monastery was secularized, there were supposed to have been “two cupboards full” of relics in the monastery.

Peak of importance (13th / 14th century)

The growth of the monastery continued in the 13th and 14th centuries. The Premonstratensian monastery Tiefenthal in the Rheingau submitted to the Eberbach monastery and the Cistercian rules in 1242. A year later the Archdiocese of Mainz reformed the Benedictine monastery Altmünster in Mainz and also made it subject to the Eberbach paternity. Numerous other women's convents followed in the course of the 13th century. A total of 16 monasteries of the Cistercian Sisters were under the Eberbach paternity.

From the 14th century, the monastery acquired patronage rights over parishes. As was done in 1324, the incorporation of the parish church to Langendiebach and 1476 to Mosbach .

Since 1256, the monastery has allowed non-members of the monastery to be buried in the basilica and in the monastery cemetery. The first known non-monastery member was Count Eberhard I. von Katzenelnbogen . The Katzenelnbogen house was one of the strongest supporters of the monastery and used the basilica as a family burial place. A family member, the Münster bishop Hermann II von Katzenelnbogen , was involved in the consecration of the basilica as early as 1186. The two Archbishops of Mainz, Gerlach and Adolf II. From the House of Nassau, and the Archbishop of Mainz, Johann I, from the House of Luxemburg, are among the important people buried in the monastery .

In 1401 the Pope awarded Boniface IX. the Eberbach abbots the right to wear the miter . They thus had an episcopal rank.

There was a school at the monastery. The monastery regularly sent members to the Paris University and the Paris Saint Bernard College to study. In Würzburg there was a college of the monastery for teacher training since 1438.

Viticulture

The monastery acquired extensive holdings of Wingerten and other agricultural goods through donations . The monastery tried to consolidate these areas into contiguous areas through purchase or exchange. These were then managed by their own departments. Wingerte were also occasionally leased in peripheral locations. Furthermore, the monastery managed to acquire production facilities for other agricultural products such as grain and fruit. In the narrow side valleys of the Rhine, the monks built or acquired several mills and regulated the streams to operate them.

Eberbach Monastery promoted wine growing and played a key role in the considerable expansion of the area under cultivation for vines in the Rheingau and the Middle Rhine Valley . A planned clearing of forest areas and the construction of new wings were based on the Grangien. There were repeated conflicts with the local population, whose commons rights were restricted by the change in use.

The Oculus Memoriae list of properties , begun in 1211, lists property rights of the monastery in over 200 locations.

From the end of the 13th century, the Wingerte were increasingly managed less independently or by compulsory workers. The monastery became more and more leased . In most cases, a rent of half or a third of the income was agreed. In addition to the lease, the leaseholder had other tax burdens such as the tithe . The lease was mostly to be provided by partial lease . The tenant had to hand over a fixed part of the harvest to the monastery. But lease agreements with non-yield-related leases in kind were also concluded. The leased property was mostly handed over to the lessee as a long lease . Although they were not allowed to resell the leased property, there were repeated sales or pledges, which led to these goods being alienated from the monastery again. Every year in July or August, a commission made up of a monk from the monastery, a viticulture expert and sometimes other people checked the condition of the leased wing and kept a record of any complaints. These logs were collected and evaluated in the monastery visitation register .

The monastery set up so-called syndicates in several cities to manage the extensive monastery property . These local administrative centers served as collection points for the natural resources. At the same time, the syndic served as the local representative of the monastery. Most of the time the office was entrusted to a member of the convent, but sometimes a secular person was also entrusted with this.

In the course of the 14th century it was possible to significantly expand the ownership of vineyards. The cause was the increasing long-distance trade. For more distant monasteries and landlords, the vineyards lost their importance, as they could now obtain wine via the market. Since these, in contrast to Eberbach, usually did not have comprehensive Rhine toll privileges, they sold their winged property to the Eberbach monastery. This enabled the Eberbach monastery to acquire the largest vineyard area in Germany with over 300 hectares of cultivation area.

The grape varieties grown in the early centuries are no longer known. Probably likely at the beginning of the cultivation of Pinot Noir (Pinot noir / Klebrot) have prevailed. This wine from the region of origin of the first monks has been documented in the Hattenheim district since 1460. From 1476 the cultivation of wine of the less noble variety Grobrot with the main cultivation area around Assmannshausen is also documented by the monastery. The focus of cultivation, however, increasingly shifted to white wines, which promised higher sales proceeds on the Cologne market.

The processes of wine fining can only be reconstructed for the early modern period. The oldest processes include racking (trussel wyn) after fermentation and purification, as well as filtration using a bag made of dense tissue (Sackwyn) . The monastery used isinglass to clarify wine as early as the 16th century . The mention of the sturgeon's swim bladder imported from the Black Sea on a shopping list for the Cologne market from 1517 is probably the oldest evidence of this procedure. The wine treatment by sulfurization is demonstrated by the bills for at least the 1,603th Large quantities of imported spices, including cinnamon bark , pepper , ginger , and nutmeg , with which the wine was presumably used to make spicy wine, are regularly listed on the monastery’s shopping lists .

Trading activity

Based on the numerous farms, the monastery built a network of financial services in the 14th century . The monastery offered people the opportunity to deposit amounts of money. In return, the monastery acted as a lender. A ban on interest was either circumvented by pledging commercial land or simply ignored. Business partners were mainly members of the regional lower nobility.

Many of the farms, especially along the Rhine, developed into guest houses for travelers. Many donations to the monastery were tied to the condition that the income was used for the benefit of pilgrims. A striking example was the courtyard at the Rheinhafen von Boppard. The courtyard had eleven guest beds, a large kitchen and a “bade budden”. The courtyard chapel, consecrated in 1302, was granted a comprehensive privilege for all visitors by Bishop Balduin von Trier in 1325 .

The farm yard around the Johanneskapelle , which existed in Limburg as early as 1211, developed into an economic center. The monastery had eleven buildings in the city. The court served the economic exchange with the population. During archaeological excavations, numerous clay floor tiles produced by the monastery in the 13th and 14th centuries were found. From here the agricultural property in the Limburg area was administered.

For the transport of goods, especially for the Cologne journeys, the monastery preferred to use the waterway. The "home port" of the ships was Reichartshausen . The most famous type of ship was the "Eberbacher Bock". Its loading capacity was up to 100 tons . Other types of ships used were "Pinth" and "Sau". The exact appearance of all of these types of ships is unclear. In addition to shipping wine, the ships were used to transport other goods between the monastery courtyards. Manure and wood were regularly transported from the Hessian Ried to the wine-growing regions.

For the convent's navigation on the Rhine it was beneficial that it was possible to obtain duty-free at all Rhine customs stations. This gave the monastery a considerable advantage over other landlords, who were particularly burdened by the customs stations that had been set up since the interregnum . The respective duty exemption for the monastery is often the oldest surviving documentary evidence of the customs station. The exemption took place:

- 1185 in Koblenz

- 1213 for all imperial customs, especially Boppard , by King Friedrich II.

- 1219 Sankt Goar by Count Dieter IV. Von Katzenelnbogen

- 1226 Bacharach by Count Palatine Ludwig I.

- 1251 Fürstenberg Castle by the Count Palatine

- 1257 Kaub by Philipp von Falkenstein-Münzenberg

- 1258 Sterrenberg by Werner von Bolanden

- 1266 Oberwesel by the von Schönburg

- 1306 Andernach / Bonn by Archbishop of Cologne Heinrich II. Von Virneburg

Conversation crisis

The separation of monks and conversationalists repeatedly led to tensions in the monastic community. The conflict was probably based on several causes. A major one seemed to be social conflict, since the conversations did not benefit from the increasing affluence to the same extent as the monks. Furthermore, the importance of conversations fell due to the increasing trend towards land leasing in the Cistercian order. At the same time, increasing commercial activity led to closer contacts between conversations and the urban bourgeoisie. Due to improved living conditions outside of the monastery and new orders, such as the Franciscans , attractive alternatives were available, so that the qualifications of the conversers decreased.

A first conversational uprising is documented for the year 1200. Another uprising in 1238 led to the general chapter in Clairvaux taking on the situation in Eberbach for the first time . However, this had little success. During further unrest in 1241, Abbot Rimund was attacked by a conversation and seriously wounded. In 1261 a converse killed Abbot Werner. This manslaughter led to a ban on conversations, which the General Chapter of the Cistercians imposed on the monastery. In the years that followed, the General Chapter approved only a few exceptions to the ban. In 1290 the visitor to the General Chapter had to take disciplinary action against Konversen again.

Similar conflicts between monks and conversations can be found in other monasteries of the order in the 13th century and repeatedly led to consultations in the General Chapter. They weren't a specific Eberbach problem.

Beginning decline (15th-18th centuries)

In the "Holy Year" 1500 the "Big Barrel" was filled for the first time. It had a capacity of approximately 72,000 liters of wine (74 ohms at 6 ohms). A list of the monastery for the period 1506–1519 shows that an average of 228 loads of wine were sold to Cologne each year. That corresponds to around 200,000 liters. Annual sales fluctuated between 98 Fuder (1516) and 440 Fuder (1507). In 1503 Cardinal Raimund Peraudi gave the abbot the Eberbach kiss tablet as a gift. The estimated area of the monastery property was about 25,000 acres , of which about 700 acres (about 2.8% of the total area) were vineyards. The focus of production was, depending on the region, on agriculture, livestock farming, viticulture and forestry. Most of the agricultural products were intended for the monastery convent and its servants' own consumption. Only a small part went on sale. Wine sales made up about 40% of the monastery's trade revenues.

During this period (1498) the total convention of monks and conversations still had 102 members. However, 15 monks died in a plague epidemic from 1500–1502.

The book catalog of 1502, which Abbot Martin Rifflinck compiled, lists 753 volumes that were kept in the monastery. Since several books were often bound together in one volume, the book inventory is estimated to be over 1000 titles. Most of these were still manuscripts. Only a few books were specially marked as printed books ( incunabula ).

However, the monastery began to slowly decline economically as early as the 15th century. Due to the sustained population growth, smaller leases were increasingly being given out. The result was falling lease rates. While the average rent at the beginning of the century was 48% of the harvest, around 1500 the monastery was only able to get lease rates of 32% of the harvest. The form of rent payments increasingly shifted to monetary payments . The increasingly poor condition of the wing was determined by the annual commissions. The most common shortcoming of the leased property was insufficient fertilization (manure) with horse manure. Due to the excessive expansion of the cultivation areas in the Rheingau and the Middle Rhine Valley, the demand for manure exceeded the production possibilities of local livestock farming .

The princes tried harder to withdraw the granted tariff privileges. In particular, the efforts of the House of Hesse hit the monastery hard. The County of Katzenelnbogen fell to the House of Hesse in 1557 after the Katzenelnbogen succession dispute between the Landgraviate of Hesse and the County of Nassau-Dillenburg . Other customs masters linked the extension of privileges to regular cash payments. As a result, the importance of the Cologne trip declined, and the monastery increasingly began to sell the wines produced at the production site to mostly Cologne wholesalers.

The monastery continued to operate as a financial service provider. It is documented that the Mainz sculptor Hans Backoffen acquired a pension insurance from the monastery in 1516. The monastery also offered wealthy people the right to buy themselves as beneficiaries, i.e. to live near the monastery in a similar way to an old people's home .

Reformation and first attempts at secularization (16th century)

In 1525 the German Peasants' War reached the Rheingau. The rebellious peasants demanded the dissolution of the monasteries in the Rheingau. The farmers camped on the juniper heather in front of the Eberbach monastery. From there they looted supplies from the monastery, almost two thirds of the large barrel was emptied. The rebellious peasants forced a declaration that all Rheingau monasteries, including Eberbach, were no longer allowed to accept monks. When the troops of the Swabian League approached, the peasants surrendered. The declaration became irrelevant. However, the Swabian Federation demanded a substantial special levy from the monasteries to finance the costs of the war.

The immediate effects of the Reformation on the monastery were minor. Only a few monks left the monastery. As a result, there was a significant decrease in the number of novices . However, the indirect consequences hit the monastery much harder. With Hessen, Nassau and Electoral Palatinate, all the important secular princes in the immediate vicinity switched to the Reformation. As a result, new foundations from these countries were not established. The Reformed rulers endeavored to obtain complete control over the church system in their respective countries. As a result, the monastery lost patronage rights and income from parishes (e.g. 1560 Mosbach near Wiesbaden).

The monastery was economically heavily burdened by the wars that resulted from the Reformation. It was repeatedly obliged to pay considerable special taxes. From the perspective of the monastery, these were particularly the Schmalkaldic War (1546) and the Prince's War ( 1552) under the leadership of Margrave Albrecht Alkibiades , in which French troops allied with the rebels advanced as far as the Rhine. Albrecht Alkibiades had the Rheingau and the Eberbach monastery plundered in the summer of 1552 during the Second Margrave War .

Already in the same year (1552) there was another threat of dissolution. As a result of the expected national bankruptcy of Kurmainz, Archbishop Sebastian von Heusenstamm endeavored to convert monasteries into domains and to incorporate them into the Mainz cathedral monastery. This took place at Johannisberg Monastery in the Rheingau. However, the monasteries Eberbach and St. Ferrutius in Bleidenstadt were able to maintain their independence.

In 1553 only 26 monks and 14 converses lived in the monastery.

Thirty Years War (17th Century)

During the Thirty Years' War , Swedish troops moved into the Rheingau on November 29, 1631 . Abbot Leonhard I. Klunckard and the convent fled to Cologne, taking the monastery archives with them. The Swedes occupied the monastery in December of that year. The extensive monastery library fell victim to the looting. The most significant loss is an unknown work by the philosopher and theologian Meister Eckhart , which today is nowhere passed down. With 48 copies, the majority of the surviving Eberbach manuscripts ended up in the Bodleian Library via William Laud , where they are now kept as Codices Laudiani . Further Eberbach manuscripts can be found in the libraries of the British Museum , in Darmstadt , Marburg , Wiesbaden , Stockholm and Uppsala .

King Gustav II Adolf gave the monastery and its extensive property to his chancellor Axel Oxenstierna , who resided in the monastery buildings from 1631. The convent did not return until 1635. After the Thirty Years War the monastery and outer courtyards were in a desolate state.

After the war, the monastery could not regain its former importance and sank completely to an Electoral Mainz state monastery. The monastery was again heavily burdened by the Reunion Wars in the second half of the 17th century.

Kurmainzer Landeskloster (18th century)

In the course of the 18th century the convent consisted of 30 to 40 monks, up to 10 conversers and almost 80 other monastery servants. During this time the monastery experienced an economic boom. Annual accounts show that surpluses have repeatedly been invested in the Frankfurt capital market . From 1704 to 1715 Abbot Michael Schnock carried out the baroque redesign of the interior of the monastery church. There was also brisk construction activity on the monastery buildings.

The Archdiocese of Mainz tried several times to secularize the monastery and to incorporate the monastery property , but the Eberbach monastery was able to resist the efforts. The monastery benefited from the fact that only about a third of the property was in the Electoral Mainz Rheingau. A further third each lay on the left bank of the Rhine, predominantly in the Electoral Palatinate and in the Landgraviate of Hessen-Darmstadt . If the monastery was abolished, other nobles, especially the Hessian landgraves, threatened to seize this property, so that it would have been lost to Kurmainz.

The dependent Cistercian Abbey Altmünster in Mainz was however abolished in 1781 by Archbishop Friedrich Karl Joseph von Erthal .

The Catholic Enlightenment writer Johannes Lorenz Isenbiehl was sentenced to a retreat in Eberbach monastery in 1778 for his writings that were considered heretical . After his failed attempt to escape, he was transferred to the vicariate prison in Mainz.

resolution

Coalition wars

The coalition wars brought radical changes for the monastery. The Rheingau and the monastery were the parade area in front of the Mainz fortress . As early as 1792, the French general Adam-Philippe de Custine threatened to occupy the monastery and demanded high taxes. In order to do this, the monastery was dependent on substantial loans. The French confiscated several monastery courtyards and set up military hospitals in them . Another appraisal by the French army in 1795 prompted the monks to leave the monastery. They fled on July 19, 1796. The French army then looted the monastery.

The monks returned to the monastery within a year. In 1797 there was a new appraisal by the French army. Respected citizens and civil servants were deported to France as leverage, and some were held captive for several years. Furthermore, thirteen works from the monastery library were confiscated and brought to Paris, including a complete edition of Zedler's Lexicon and the Historia philosophicae doctrinae de ideis by Johann Jakob Brucker . The Convention even had to acquire a required edition of the German Encyclopedia , as it did not even have it. A statue of the Virgin Mary created in 1420 was also confiscated by the French. It is now in the Louvre in Paris .

Since 1799, the monastery no longer received any income from property on the left bank of the Rhine. In 1803 the monastery was still litigating to replace the war-related damage against Kurmainz and later against the Principality of Nassau-Usingen .

secularization

With the Treaty of Lunéville (February 9, 1801), the loss of property on the left bank of the Rhine was officially confirmed, and with the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss the monastery and the property on the right bank of the Rhine fell to the Principality of Nassau-Usingen. The monastery was part of the compensation of the principality for its losses on the left bank of the Rhine, in particular the county of Saarbrücken . The Nassau seizure of the Rheingau, and with it the monastery, took place on October 11, 1802 in anticipation of the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss by Government Councilor Philipp Ludwig Rößler.

Immediately after the seizure of the property, a commission of the prince under government councilor August Ludwig Freiherr von Preuschen began an inventory of the monastery property in October / November 1802. The goal of the Protestant principality was the rapid control of the monastery property. The abolition of monasteries was common practice at this time, also outside Nassau. While the principality abolished all other wealthy monasteries in spring 1803 at the latest, Eberbach still existed. The cause was a dispute between the Duchy of Nassau and the Grand Duchy of Hesse over the distribution of the pension costs of the monastery members.

According to a decree by Prince Friedrich August von Nassau, the monastery was dissolved on September 18, 1803. The remaining 22 monastery members had to vacate the monastery by November 27, 1803. The abolition process of the monastery took place in accordance with the regulations of the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss and was carried out with considerable bureaucratic meticulousness.

The last abbot Leonhard moved to his hometown Rüdesheim . From there he maintained contact between the former members of the monastery. He continued the monastery book of the dead until his own death in 1818. Other former members of the monastery took up the profession of priest or, because of their age, retired from their families.

The aim of the administration was the rapid liquidation of the monastery. The princely administration took over the business operations of the monastery. Since this consisted mainly of the administration of small and very small leases, she was initially overwhelmed by organizing them. Even before the monastery was formally abolished, the Drais and Steinheim monastery courtyards were transferred to the Nassau diplomat Hans Christoph Ernst von Gagern . After the monastery was abolished, other economic goods were auctioned off to the public.

The government took over the direct wine-growing and agricultural operations at the monastery itself. Some of the buildings have been rededicated for this purpose. The monastery church became a barn. Most of the buildings, however, remained vacant. Structural elements such as the cloister , reminiscent of its function as a monastery, were demolished on the orders of the Nassau government. The graves of the two Archbishops of Mainz were nailed up. Six grave slabs of the Counts of Katzenelnbogen and Nassau and other components were used to erect and decorate the artificial ruins of Mosburg in the Biebrich Castle Park . The ornate copper gutters were dismantled in the monastery at the instigation of Christian Zais and attached to the old Wiesbaden Kurhaus . Valuable inventory was brought to Biebrich Castle , the rest was gradually auctioned off. Church objects were distributed to numerous churches. The organ of the basilica, built by Johann Jakob Dahm from 1706 to 1708 , was brought to the Mauritius Church in Wiesbaden, where it burned in 1850. The monastery archive was incorporated into the ducal central archive in Idstein Castle. Most of the remaining 8,000 volumes in the monastery library were lost; only a few objects ended up in the Nassau State Library .

Foreign property

Eberbach Monastery was wealthy in Oppenheim before 1225 and owned a monastery courtyard with a chapel there. The latter, a building from the 13th century, has been preserved, but profaned and today serves as the dining room of the Dahlem winery (Rathofstraße 21). On the outside there is a coat of arms of the abbot Adolph Dreimühlen marked in 1731, inside a similar one with the year 1733. The abbot apparently had the chapel renovated again after the city was destroyed in 1689; until 1394 it should have been a synagogue.

Abbots of the Eberbach Monastery

For the Eberbach monastery there are 58 abbots by name. A book of the dead of the monastery was only created between 1369 and 1371. Only the abbots who died in office are listed here. Abbots who resigned or moved to another monastery during their lifetime were not recorded before the 14th century. Therefore, the order and terms of office of the earlier abbots were reconstructed on the basis of the documents received from Hermann Bär in the 19th century. In order to resolve contradictions in the list, the existence of another abbot (Arnold I., 1152-1159) was assumed. However, this theory is now considered flawed.

| No | Term of office | Surname | origin | Grave no | annotation | image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

12th Century |

||||||

| 1 | 1136-1157 | Ruthard | Common wall niche grave of Abbots Ruthard, Arnold and Gerhard |

|

||

| 2 | 1158-1165 | Eberhard | Common wall niche grave of Abbots Ruthard, Arnold and Gerhard | |||

| 3 | 1171-1178 | Gerhard | Common wall niche grave of Abbots Ruthard, Arnold and Gerhard | |||

| 4th | 1178-1191 | Arnold | ||||

| 1192-1196 | Gerhard | 2. Term of office | ||||

| 5 | 1196-1203 | Mefried | ||||

|

13th Century |

||||||

| 6th | 1203-1206 | Albero | ||||

| 7th | 1206-1221 | Theobald |

|

|||

| 8th | 1221 | Konrad I. | ||||

| 9 | 1222-1227 | Erkenbert | ||||

| 10 | 1228-1247 | Rimund | ||||

| 11 | 1248-1258 | Walter | ||||

| 12 | 1258-1261 | Werner | murdered by a lay brother | |||

| 13 | 1262-1263 | Heinrich I. | ||||

| 14th | 1263-1271 | Ebelin | ||||

| 15th | 1272-1285 | Richolf | ||||

| 16 | 1285-1290 | Henry II |

|

|||

| 17th | 1290-1298 | Siegfried | ||||

| 18th | 1298-1306 | Johann I. |

|

|||

|

14th Century |

||||||

| 19th | 1306-1310 | Peter | ||||

| 20th | 1310-1346 | Wilhelm |

|

|||

| 21st | 1346-1352 | Nicholas I. | ||||

| 22nd | 1352-1369 | Henry III. | Cologne | 1 | ||

| 23 | 1369-1371 | Konrad II. | 2 | |||

| 24 | 1372-1392 | Jacob | Eltville | 3 | ||

| 25th | 1392-1407 | Nicholas II | Boppard | 4th |

|

|

|

15th century |

||||||

| 26th | 1407-1436 | Arnold II | Heimbach | 5 |

|

|

| 27 | 1436-1442 | Nicholas III | Chew | 6th |

|

|

| 28 | 1442-1456 | Tilmann | Johannisberg | 7th |

|

|

| 29 | 1456-1471 | Richwin | Lorch | 8th |

|

|

| 30th | 1471-1475 | Johann (es) II. | Germersheim | 9 |

|

|

| 31 | 1475-1485 | Johann (es) III. Bode | Boppard | 10 |

|

|

| 32 | 1485-1498 | Johann (es) IV. Nobleman | Rudesheim | 11 |

|

|

| 33 | 1498-1506 | Martin Rifflinck | Boppard | 43b |

|

|

|

16th Century |

||||||

| 34 | 1506-1527 | Nicholas IV | Eltville | 12 |

|

|

| 35 | 1527-1535 | Lorenz | Dornberg | 13 | Common grave slab with Wendelin |

|

| 36 | 1535 | Wendelin | Boppard | 13 | Common grave slab with Lorenz | |

| 37 | 1535-1539 | Karl Pfeffer | Mainz | 24 |

|

|

| 38 | 1539-1541 | Johann (es) V. Bertram | Boppard | 14th |

|

|

| 39 | 1541-1553 | Andreas Bopparder | Koblenz | 15th |

|

|

| 40 | 1553-1554 | Pallas Brender | Speyer | 16 |

|

|

| 41 | 1554-1565 | Daniel | Bingen | 17th |

|

|

| 42 | 1565-1571 | Johann (es) VI. Moon real | Boppard | 18th |

|

|

| 43 | 1571-1600 | Philipp Sommer | Kiedrich | 19th |

|

|

|

17th century |

||||||

| 44 | 1600-1618 | Valentin Molitor | Rauenthal | 20th |

|

|

| 45 | 1618-1632 | Leonhard I. Klunckard | Rudesheim |

|

||

| 46 | 1633-1642 | Nikolaus V. Weinbach | Oberlahnstein | 22nd |

|

|

| 47 | 1642-1648 | Johann (es) VII. Rumpel | Ballenberg | 21st | Common grave slab with Balthasar |

|

| 48 | 1648 | Johann (es) VIII Hofmann | Miltenberg | |||

| 49 | 1648-1651 | Christoph Haan | ||||

| 50 | 1651-1653 | Balthasar Bund | Aschaffenburg | 21st | Common grave slab with Johann (es) VII | |

| 51 | 1653-1665 | Vincent Reichmann | Eltville | 23 |

|

|

| 52 | 1665-1666 | Eugene Greber | Mainz | |||

| 53 | 1667-1702 | Alberich Kraus | Boxberg | 25th |

|

|

|

18th century |

||||||

| 54 | 1702-1727 | Michael Schnock | Kiedrich | 26th |

|

|

| 55 | 1727-1737 | Adolph I. Dreimü (h) len | Eltville | 27 |

|

|

| 56 | 1737-1750 | Hermann Hungrichhausen | Mengerskirchen | 28 |

|

|

| 57 | 1750-1795 | Adolph II Werner | Salmunster |

|

||

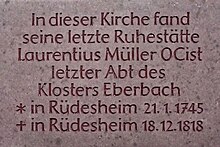

| 58 | 1795-1803 | Leonhard II. Müller | Rudesheim | forced to leave the monastery |

|

|

memory

It was not until years after the abolition that the director of the Eberbacher Anstalten, Philipp Heinrich Lindpaintner, and the Society for Nassau Antiquity and Historical Research began to show historical interest in the cultural heritage of the monastery.

Particularly valuable objects such as the Oculus Memorie could be acquired again after they had been handed in as waste paper during the secularization phase. Gravestones were returned to the monastery after years of being used as building material.

Historical research was promoted by Friedrich Gustav Habel and above all Karl Rossel . Rossel wrote several books about the monastery. He also organized the publication of the "Diplomatic History of Eberbach Abbey in the Rheingau". The work was written by Hermann Bär , the last bursar (financial administrator) of the monastery. This work, which is still used today, describes the history of the monastery in detail, but ignores particularly negative aspects such as the conversational uprisings of the 13th century.

After secularization

After the secularization , only a small part of the buildings was needed for agricultural use. Most of the monastery was empty. The government tried to put this to use. In 1808 a temporary depot of the Nassau army was set up .

Workhouse

From 1811 the establishment of a correctional facility for the Duchy of Nassau began in the vacant buildings. In the correctional facility, inmates should be brought to work through work to improve their health. The usual inmates were (in the opinion of the parents) difficult to raise children, (in the opinion of the wives) inactive husbands, invalids, single mothers, apprehended beggars and similar persons. Since being in the correctional facility was not considered a punishment, conviction was not a requirement for detention. In 1832 there were a total of 447 men and 87 women in the institution or were newly incarcerated. The usual length of stay was between three months and five years.

Sanatorium

Due to an edict of the Duchy of Nassau, the "Eberbach Madhouse" was set up on August 16, 1815 from individual parts of the monastery. It was the first psychiatric clinic in Nassau and one of the first in Germany. Most of the inmates were long-term familyless patients. A special house for madmen was built for the institution on the monastery grounds in 1827 . In 1832 there were 62 men and 27 women in the institution or were newly transferred here. In the course of the year twelve people left the institution and five died. The sanatorium and the workhouse were under joint management. The sanatorium was housed in the monastery until 1849. Then the move to the newly built complex of buildings of the sanatorium and nursing home on the Eichberg near the monastery took place. From 1874 to 1880 there was another branch of the sanatorium on the Eichberg in the monastery. The Eichberg Clinic for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy was the forerunner of Vitos Rheingau until 1973 .

Different uses

The correctional facility in Eberbach was closed in 1873. From 1877 a central prison was established in the monastery buildings . A women's prison already existed from 1840 to 1872 in the former house for madmen. When the new building at Diez Prison was completed in 1912, all inmates were moved there.

After the prison moved out, the monastery was solely available to the wine-growing domain. This partially rented it to the 18th Army Corps to set up a military convalescent home. This was documented from 1914. After the First World War, the monastery was under the occupation authorities until 1921. It was then taken over by the Prussian and, from 1945, the Hessian Ministry of Agriculture .

What happened in Eberbach Monastery during the Nazi era has largely not been researched. A project led by the Fulda historian Sebastian Koch aims to clarify this with the support of the foundation.

Tourist use

From the middle of the 19th century, the monastery turned more and more into a tourist destination. This was accelerated by increasing research into the monastery and its history. Until the beginning of the 20th century, however, its tourist use was in contradiction to its use as a prison.

During the Weimar Republic , the tourist use of the monastery experienced an upswing. It was specifically promoted by the domain administration as a counter-program to the planned reopening. The measures included the establishment of the monument protection association (1921/22), the temporary opening of a youth hostel (1923) and the organization of regular guided tours from 1925. From 1927 the administration even organized a temporary wild boar breeding program in the Saugraben as tourist entertainment.

Plans to reopen the monastery

After the end of the Kulturkampf , the Limburg diocese began to rebuild secularized monasteries. The driving force was the abbot of the Marienstatt monastery , which was re-established in 1888, and later Bishop Dominikus Willi . The effort found support from the population and was politically supported by the Center Party . In principle, the government was ready to sell the monastery building to the diocese. However, the government was not prepared to sell any agricultural land from the domain, so that the monastery was not re-established due to the lack of an economic concept.

After the First World War, Belgian Trappists tried to repopulate the monastery from 1921 onwards . The effort, during the Rhineland occupation , led to controversial opinions. The diocese welcomed the plans, but demanded that the repopulation must take place under Marienstatter jurisdiction . The Catholic population supported the effort. The request was rejected by the Prussian press, the government and especially the domain administration. There was talk of an Eberbach culture war . Against this background, the monument protection association around Ferdinand Kutsch, supported by the domain administration, was founded on January 5, 1922. The efforts ended with the economic crisis in 1923. A new addition was not made, as Marienstatt through the re-establishment of the monasteries Himmerod (1922) and Hardehausen (1927) was busy.

A third attempt at resettlement in the 1950s with a Bohemian convention in exile failed, like the previous ones, for financial reasons.

Alternate seat

After the Second World War, the monastery served as a reception camp for refugees. In 1950, 172 people still lived in its buildings.

During the Cold War , Eberbach served the Hessian state government as an emergency seat. Some rooms, which were equipped with card tables, radio systems, emergency power supply and explosion-proof lighting, remained inaccessible even to the monastery administration.

Younger story

When the monastery was flooded by rain on the night of April 26, 2005, immense damage occurred. Large parts of the monastery complex were flooded. The flooding occurred after the Kisselbach overflowed its banks due to heavy rain and the 18th century drainage canal that ran under the monastery collapsed.

On March 5, 2008, Eberbach Monastery was added to the list of cultural property worthy of protection in accordance with Article 1 of the “ Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict ”.

On March 20, 2010, the monastery was included in the “Charte européenne des Abbayes et Sites Cisterciens” in the former lay dormitory in Eberbach. This was brought into being in 1988 by representatives of some former Cistercian monasteries in the country of origin of the order, France. The association now has more than 160 members, mainly in the francophone area; In the German-speaking area there are now 22 Cistercian sites.

In 2010, the German Wine Institute (DWI) honored “Highlights of Wine Culture” in the German wine-growing regions for the first time. The Eberbach Monastery is one of the first 13 highlights of wine culture.

On April 20, 2016 in the Monastery Basilica recording a "theme show" who found RTL - casting show Germany Idol instead.

Todays use

Eberbach Monastery Foundation

With effect from January 1, 1998, the State of Hesse brought the entire abbey complex as real estate into the property of the Eberbach Monastery Foundation , a foundation under public law with legal capacity . The foundation has the mandate to preserve the architectural and cultural monument of Eberbach Monastery in the long term through moderate, gentle and appropriate use of the site and to preserve its historical winemaking tradition. As part of this mandate, a target system was developed in 2002 and approved by the foundation committees, which represents the various tasks that are necessary to fulfill the overall mandate in a hierarchical manner. In October 2015, the Eberbach Monastery Foundation was nominated for the KOMPASS Prize by the Association of German Foundations in the category “Foundation Management - Success through Professional Management” .

Foundation funding

The to fulfill the o. A. Current funds required for maintenance and operation of the facility are to be generated by the foundation itself. This is the purpose of the entrance fees and guided tour fees levied on visitors, as well as the rental of rooms for events, the lease income from the monastery catering or the purchase of products in the monastery shop. For the continuation of the program "General renovation of Eberbach Monastery", which has been running since 1986. In some cases, damage to the substance that has accumulated over centuries is repaired, the foundation receives donations from the state.

Foundation bodies

The foundation organs anchored in the constitution are the board of trustees and the board of directors. The term of office of all board members is six years. With the exception of the executive board, all board members are volunteers.

The board of trustees is the supervisory body of the foundation and has to ensure that the board of directors pursues the permanent and sustainable fulfillment of the foundation's purpose. The board of trustees consists of eight members, who are sent by three Hessian state ministries entrusted with the foundation tasks, the Hessische Staatsweingüter GmbH Kloster Eberbach, the city of Eltville and the Rheingauer Weinbauverband. The board represents the foundation in and out of court, conducts its business and takes care of all administrative tasks assigned to it.

Hessian state wineries

After secularization in 1803, the abbey's farms became state property as a wine-growing domain (Nassau: 1803–1866; Prussia: 1866–1945; Hesse: 1945–1997). The Hessische Staatsweingüter GmbH Kloster Eberbach are today the largest German winery. They run a vinotheque in the monastery buildings . The central winery and a vinotheque of the winery are located on Steinberg not far from the monastery.

The vineyards that were formerly owned by the monastery - above all the enclosed Steinberg, laid out by the Cistercians - are now predominantly owned by the Hessian state wineries. Of the approximately 200 hectares of cultivation area, ¾ are planted with Riesling . But Chardonnay , Pinot Blanc , Pinot Gris , Pinot Noir and Dornfelder are grown. The property includes the Steinberg and parcels in prime locations such as the Rauenthaler Baiken , Erbacher Marcobrunn , Assmannshäuser Höllenberg and Rüdesheimer Berg .

Culture

After several repairs, Eberbach serves as a venue for cultural events and as a conference center as well as a film set. The accessible areas can be visited daily either individually or with a guide. Bookable rooms are available for conferences and events. Since June 16, 1995, a museum and a branch of the Eltville registry office have been located in the closed building . There are restaurants and a hotel on the site . The former monastery is visited by around 300,000 people annually.

The rooms of the monastery, especially the basilica, are one of the main venues of the Rheingau Music Festival . A total of 30 concerts took place in the monastery during the 2013 festival.

Almost all of the interior shots for the film The Name of the Rose were shot in the monastery in the winter of 1985/1986 .

The architectural researcher Hanno Hahn , son of Nobel Prize winner Otto Hahn , received his doctorate summa cum laude from Harald Keller at the University of Frankfurt am Main in 1953 with a dissertation on the church of the Cistercian Abbey of Eberbach in the Rheingau and the Romanesque architectural art of the Cistercians in the 12th century . The writer Berndt Schulz used the monastery as a backdrop for his detective novels Regenmord (2007) and Die ver Zauberierter Frauen (2011).

building

The core area of the monastery is a structure consisting of a basilica, a cloister and a conversing wing. This group of buildings encloses a rectangular interior. This is divided by the library building into the larger cloister (in front of the enclosure) and the smaller Klostergasse (in front of the Konversenbau).

The Kisselbach runs east of the core area. The building of the old hospital is on the other side of the stream . After this had been rededicated for wine-making purposes, the Kisselbach was built over with the new hospital. To the west of the Konversenbau are the so-called "Säugräben" and on higher terraces there are various agricultural buildings. Further farm buildings and workshops are located north of the core area.

There is only access to the monastery on the south side. Originally, entry was only possible through the gatehouse. More gates were built in later centuries. The entire facility is enclosed by a circular wall.

The entire complex forms a cultural monument of European standing. The coincidence of several factors is decisive for the meaning. It is an early monastery, based on the Cistercian ideal, which has been handed down in full. The buildings preserved in the original have a special artistic quality.

Building history

The location of the monastery, above the Rheingau and surrounded by wooded ridges of the Taunus , corresponded to the ideal of solitude of the early Cistercian movement. The monks should concentrate on a godly life, isolated from the world, away from the important trade routes.

Originally the Cistercians lived in the abandoned buildings of the former Augustinian canons. These were located in the area of the old hospital east of the Kisselbach. Only the strong growth in the number of convent members made it necessary to initiate the Romanesque new building of today's monastery from 1140 onwards . This was completed around 1220. In the following two centuries the buildings were rebuilt and changed several times in the Gothic style.

Plans to rebuild the monastery in the 17th century under Abbot Leonhard I. Klunckhart could not be realized due to the Thirty Years War. In the late 17th and 18th centuries, there were further baroque reconstruction work on the monastery, which, however, did not change the core of the entire complex. The old church of the Canons' Monastery was demolished in the 18th century.

Thanks to the continuous state use without significant investments since the secularization, the entire complex was largely preserved. In the 20th century, extensive renovations were carried out on the entire complex, taking into account the preservation of historical monuments . The Romanesque state was partially restored. The house for the madman, the biggest structural change of the 19th century, was demolished again.

basilica

The monastery basilica was built on the southern edge of the core area of the monastery. It forms the visually dominant building of the monastery for visitors coming from the gatehouse. It is a three-aisled high Romanesque pillar basilica with a transept. The nave, transept and choir have a roof ridge running at the same height. Construction of the Romanesque basilica began in 1140. After construction interruptions around 1160–1170, the altar was consecrated in 1178. The consecration of the whole church took place in 1186 by the Archbishop of Mainz Konrad I von Wittelsbach in the presence of the Münster bishop Hermann II von Katzenelnbogen . In the original plan, the choir was supposed to be significantly lower than the nave, but this plan was abandoned during the construction phase.

In front of the south aisle are nine Gothic chapels . They were added in several construction phases between 1313 and 1340 and originally served as donated grave chapels . During this construction phase, large Gothic windows were broken into the choir , of which the southern one has been preserved.

During baroque renovation work in the monastery, the inclination of the roof of the nave and transept was increased. The church was crowned with two ridge turrets with an onion-shaped hood. The larger one is above the crossing , the smaller one above the western nave . Further baroque modifications of the Romanesque building were dismantled during the restoration in 1935–1939.

Inside the 76.2 × 33.4 meter building, the closed Romanesque overall impression dominates. The basilica is built on the plan of the Latin cross. Simple round arches support the groin vault. The nave has six arches, the north and south transepts and the choir are separated from the crossing by an arch. The walls are smooth and unadorned. Starting from the Gothic phase, the walls were painted and the floor was covered with ornamental colored tiles.

On the east side of the transept there are three chapels each on the north and south transepts. Inside, remains of the stucco from the baroque redesign of the early 18th century have been preserved.

The choir stalls that originally shaped the church interior and the choir screen in the nave are no longer there. The Gothic tombstones kept inside the church were badly damaged when the building was used as a stable . Almost all of the grave slabs are no longer in their original location.

Today the church is used for concerts, especially the Rheingau Music Festival . The church can accommodate 1,400 people. Services are only held on special occasions.

Closed buildings

Eastern enclosure

The cloister buildings of the monastery are located directly north of the basilica . The time when the building was constructed is unknown. The oldest parts of the building are likely to go back to the new building from 1140. The buildings are built in the Romanesque style, but were redesigned in the early Gothic style in the 13th century.

The east wing of the enclosure forms the extension of the transept of the basilica. As part of the Gothic redesign around 1250, the building was lengthened and has since protruded far beyond the cloister. It is home to the ground floor of the Basilica of the Armarium , the sacristy , the chapter house , the outlet, the Parlatorium and today as a wine cellar used Fraternei . After the library was moved to the library building, the armarium was rededicated as a burial site.

The chapter house can be entered from the cloister. It received its high Gothic form around 1350. The vaulted star rising from the individual central column supports the room like an umbrella. The room is surrounded all around with two ascending rows of stone benches. Around 1500 it was decorated with tendril and flower paintings.

The 48-meter-long two-aisled hall of the fraternity takes up most of the ground floor of the eastern cloister. The three-meter high room is spanned by a groin vault. Since the surrounding area is already rising here, it is partially below the terrain level. In today's early Gothic form, it was built around 1250 as part of a monastery expansion. Originally it was a work room, probably the monks' office. Since the late Middle Ages, the room served as the monastery wine cellar. As the valuable wines were stored here, it was called the Cabinettkeller . The term Kabinett for German quality wines is derived from here.

On the upper floor is the monk's dormitory, a 74 meter long and 14 meter wide two-aisled hall. With over 1000 m², this early Gothic room is one of the largest non-sacred rooms of the Middle Ages. Its ribbed vault is supported by low columns with carved capitals . Since the ground rises slightly to the north, it looks even more impressive. The dormitory is directly connected to the transept of the basilica via a staircase. Today the rooms belong to the abbey museum. In the monastery it served as a dormitory for up to 150 monks.

Northern enclosure

In the area of the northern enclosure, several buildings were erected around 1186. The actual refectory stretched lengthways to the north. After several renovations in the 13th and early 16th centuries, the building was rebuilt in Baroque form between 1720 and 1724. The existing building fabric was partially included on the ground floor. It is a two-storey building with a gable roof, which has a central projection on the north side .

The north building comprises the monk's refectory , the kitchen area and the portico on the ground floor . The winter chapter room, the warming room and smaller individual rooms are located on the upper floor. Today the building is used as an abbey museum.

The main room on the ground floor is the monk's refectory in baroque style. During the renovation in the 20th century, the wall paneling was partially renewed. The baroque stucco ceiling by Daniel Schenk has been preserved. Nothing can be proven of the presumably existing ceiling painting. The hall now serves as a space for festive events. Next to the monk's refectory is the former monastery kitchen. Today the room is used as the foyer of the monk's refectory.

Cloister

The eastern and northern enclosure and library building enclose an inner courtyard that was used as a cloister and monastery garden. The north side is partly Romanesque, partly Gothic like the west side. Parts of the Romanesque cloister were demolished after the secularization in 1804. They were used as spoilers in buildings such as the Moosburg in the Biebrich Castle Park or the parish church of Kelkheim-Münster . The well chapel located inside the monastery garden was also demolished. The fountain could be restored in the course of the monastery renovation in the late 20th century, partially using original parts.

Library building

as spherical panorama

The library building is a half-timbered floor that overbuilds the western part of the cloister and partially protrudes into the Klostergasse. A five-sided stair tower juts out into the cloister garden. During the renovation in the 20th century, the late Gothic half-timbering was exposed again. The building, which was built between 1478 and 1480, served as the monastery library when, due to the spread of letterpress printing, the armarium in the eastern enclosure no longer offered sufficient space. The building is one of the oldest surviving library buildings in Germany. The stair tower was built around 1500. The construction dates could be checked dendrochronologically during the renovation in the late 20th century . The abbey museum has been on the upper floor since 1995. This contains the oldest stained glass window (around 1180) preserved within the German Cistercian culture, the original capitals from the cloister, which have been replaced by copies, as well as various sculptures, paintings, baroque furniture and archaeological finds. The name Schwedenbau for this building was only used in the 19th century, it cannot be proven in older documents.

Konversenbau

The Konversenbau was built from 1190. With a length of 109 meters, including the extension, the Konversenbau is the longest building in the monastery area. It is separated from the inner exam area by Klostergasse. However, there is a transition to the northern enclosure via the stair tower and the portico. Originally the building was a two-story building, but as part of the redesign in the 16th century, it was raised by another floor, extended by the bakery and the fountain house and given a hipped roof.

On the ground floor there are two two-aisled halls. A corridor runs between the two halls, which was the original entrance to the inner monastery area. The northern one was intended as a wine cellar (cellarium) for the monastery from the start. The lay refectory was in the southern one. This 47 meter long room has been preserved almost unchanged in its original Romanesque form. Twelve historical wine presses from the period from 1668 to 1801 are on display in the lay refectory.

The lay dormitory is located on the upper floor. This two-aisled hall from the beginning of the 13th century is 85 meters long and 13 meters wide and is the largest preserved non-sacred hall from the Middle Ages in Europe. During the renovation work in the 1960s, it was returned to its original Romanesque state. Today the hall is used for cultural events and traditional wine auctions.

The Burse (central administration of the monastery property) has been located on the upper floor since the 17th century . These rooms are not open to the public. They are rented out by the Eberbach Monastery Foundation.

Hospital buildings

To the east of the core area of the monastery, on the other side of the Kisselbach, is the old hospital . The late Romanesque building originally served to accommodate guests of the monastery as well as nursing. In the baroque phase the house was rebuilt in 1721/22 and given a hipped roof. The interior is a three-aisled room 39 meters long and 16 meters wide. In this pillars support the late Romanesque groin vault. The column capitals are very similar in design to those of the Limburg Cathedral, which was built around the same time, so that it is assumed that the same artists were active on both buildings.

On the north side of the hospital, a two-storey residential building in the high Gothic style was added.

On the east side of the hospital there is a new building for the state winery from 1927, which today houses the vinotheque of the Hessian state winery.

Between the old hospital and the eastern enclosure, the new hospital was built in 1752/53 as a connecting structure during the baroque phase. The Kisselbach was built over with this two-story building. Today this house serves as a building for the entrance to the monastery area.

Outbuildings

Northern farm buildings

The buildings north of the core area of the monastery complex included the workshops that were necessary for the operation of the monastery.

Western farm buildings

The buildings to the west of the Konversenbau in the core area were originally primarily used for agricultural purposes. There were stables, barns, mills and the wine press house. The buildings preserved here come exclusively from the 17th and 18th centuries. Century. Today they are used to accommodate the hotel and a catering establishment.

Gate and gatehouse

In the Middle Ages, the gatehouse was the only access to the monastery. Century is enclosed by a 1100 meter long curtain wall. The wall is more than a meter thick in places and up to five meters high.

The Romanesque gatehouse was built in the 12th century. In the house there are two arched gates of different sizes for pedestrians and wagons . In the house there was a room for the porter, guest rooms and a chapel. The gatehouse was redesigned in baroque style around 1740 and provided with a statue of St. Bernard . A square with a fountain was created in front of the gatehouse. The headquarters of the Rheingau-Taunus Kultur und Tourismus GmbH are located in the gatehouse .

Above the gatehouse there is a late baroque gate built in 1774 in the wall. Above the archway is the coat of arms of Abbot Adolf II. Werner. It is crowned by statues of the monastery patrons and the founder. In the middle is St. Mary Immaculate, on the left John the Baptist and on the right St. Bernard.

Gardens

In 2004 the Eberbach Monastery Foundation launched a limited competition for the redesign of the 7.5 hectare outdoor area. The winning design concept by the Berlin office of Bernard and Sattler Landscape Architects is based on a fundamental analysis of the essence of the original Cistercian world of thought and its fundamental principles. The aim of the redesign of the outdoor facilities in Eberbach Monastery is to convey the simple clarity of the Cistercian view of the world to the visitor and to emphasize the specialty of the building ensemble. The structural implementation of the outdoor facilities has been taking place gradually since 2006. Completion is planned for 2014.

In April 2011, the redesign of the outdoor facilities was awarded one of six awards given by the State of Hesse together with the Chamber of Architects and Urban Planners of Hesse for the architecture prize “Distinction of exemplary buildings in the State of Hesse” from 84 submitted works.

Abbey garden and orangery

The abbey garden extends south of the basilica to the gatehouse. In the middle of it, today's orangery was built in 1755/56. This is a baroque building with a hipped roof. The monk's cemetery was originally located in this area .

Prelate Garden and Abbey

To the southwest of the basilica are the Prelate Garden and the Abbot Garden, which is a little higher up. These are baroque ornamental gardens that rise over several terraces. The gardens are dominated by the abbey. This half-timbered garden house was built in 1722.

Hospitalberg

The slope to the east of the old hospital was redesigned as a vineyard during renovation in the 20th century. Up until the 17th century, viticulture was documented on the Hospitalberg, after which it was used as an orchard.

literature

- Daniel Deckers , Till Ehrlich , Martin Wurzer-Berger, Gerwin Zohlen, Ralf Frenzel (eds.): Eberbach Monastery. History and wine. Tre Torri, Wiesbaden 2015, ISBN 978-3-944628-71-4 .

- Peter Engels, Hartmut Heinemann, Hilmar Tilgner: Eberbach. In: Friedhelm Jürgensmeier, Regina Schwerdtfeger (edit.): The monastery and nunnery of the Cistercians in Hesse and Thuringia. ( Germania Benedictina, Volume IV / 1.) St. Ottilien 2011, ISBN 978-3-8306-7450-4 , pp. 383-572.

- Wolfgang Einsingbach, Wolfgang Riedel: Eberbach Monastery in the Rheingau. 17th edition. Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-422-02166-2 .

- Jürgen Kaiser, Josef Staab : The Cistercian monastery Eberbach in the Rheingau. Regensburg 2000, ISBN 3-7954-1271-4 .

- Heinrich Meyer zu Ermgassen (arr.): The Oculus Memorie. A list of goods from 1211 from the Eberbach monastery in the Rheingau. Volumes 1–3 ( Publications of the Historical Commission for Nassau, Volume XXXI). Historical Commission for Nassau , Wiesbaden 1981–1987.

- Heinrich Meyer zu Ermgassen: Hospital and Brotherhood. Guest services and poor relief of the Cistercian monastery Eberbach in the Middle Ages and modern times. ( Publications of the Historical Commission for Nassau, Vol. 86). Historical Commission for Nassau, Wiesbaden 2015, ISBN 978-3-930221-32-5 .

- Nigel F. Palmer : Cistercians and their books. The medieval library history of Eberbach Monastery in the Rheingau. Regensburg 1998, ISBN 3-7954-1189-0 .

- Gisela Rieck: An abbot in the turmoil of the French Revolution. 200th anniversary of the death of the last Eberbach abbot Leonhard II. In: Cistercienser Chronik 126 (2019), pp. 64–70.

- Wolfgang Riedel (ed.): The Cistercian monastery Eberbach at the turn of the ages. Abbot Martin Rifflinck (1498–1506) on the 500th year of death. ( Sources and treatises on the Middle Rhine Church history, Volume 120.) Mainz 2007, ISBN 978-3-929135-53-4 .

- Hellmuth Gensicke : State history of the Westerwald . 3. Edition. Historical Commission for Nassau, Wiesbaden 1999, ISBN 3-922244-80-7 .

- Werner Rösener: The conversations of the Cistercians . In: Nassau Annals . tape 111 . Verlag des Verein für Nassau antiquity and historical research, 2000, ISSN 0077-2887 , p. 13-27 .

- Hartmut Heinemann: The abolition of Eberbach monastery in 1803 . In: Nassau Annals . tape 115 . Verlag des Verein für Nassau antiquity and historical research, 2004, ISSN 0077-2887 , p. 37-46 .

- Volkhard Huth: Visionaries in Eberbach . In: Nassau Annals . tape 114 . Verlag des Verein für Nassau antiquity and historical research, 2003, ISSN 0077-2887 , p. 37-46 .

- Otto Volk: Economy and society on the Middle Rhine from the 12th to the 16th century . Historical Commission for Nassau, Wiesbaden 1998, ISBN 3-930221-03-9 .

- Hilmar Tilgner, Siegbert Sattler: The renovation of the Eberbach monastery in the Rheingau: The library building . In: Nassau Annals . tape 109 . Verlag des Verein für Nassau antiquity and historical research, 1998, ISSN 0077-2887 , p. 175-202 .

- Hilmar Tilgner: Armarium and library building: the library rooms in the Cistercian monastery Eberbach from the 12th century to 1810 . In: Wolfenbüttel notes on book history . 23, issue 2. Harrassowitz, 1998, ISSN 0341-2253 , p. 132-181 .

- Hilmar Tilgner: The building history of the Eberbacher Klausur around 1500: Aspects of the renovatio under Abbot Martin Rifflinck and the later fate of these redesigns . In: The Cistercian monastery Eberbach at the turn of the ages. Abbot Martin Rifflinck (1498–1506) on the 500th year of death . Mainz 2007, ISBN 3-929135-53-1 , p. 369-406 .

Web links

- kloster-eberbach.de Official website of the umbrella brand Kloster Eberbach (Stiftung Kloster Eberbach, Hessische Staatsweingüter GmbH Kloster Eberbach, restaurants in Kloster Eberbach GmbH, Freundeskreis Kloster Eberbach eV)

- Eberbach, Rheingau-Taunus-Kreis. Historical local dictionary for Hesse (as of July 26, 2013). In: Landesgeschichtliches Informationssystem Hessen (LAGIS). Hessian State Office for Historical Cultural Studies (HLGL), accessed on June 26, 2013 .

- Archives about Eberbach Monastery in the Hessian Main State Archive, Wiesbaden

- Dagmar Söder, State Office for Monument Preservation Hesse: Eberbach Monastery Landscape The monastery as a commercial enterprise and its traces in the Rheingau landscape (PDF; 58 KB)

- Literature about Eberbach Monastery in the Hessian Bibliography

- Selected bibliography at Cistopedia .

- Alphabetically or thematically structured bibliography on the homepage of the Freundeskreis Kloster Eberbach eV

- Eberbach Monastery during the Nazi era

Individual evidence

- ↑ Wolfgang Einsingbach, Wolfgang Riedel: Eberbach Monastery in the Rheingau. 2007, p. 8.

- ↑ Wolfgang Einsingbach, Wolfgang Riedel: Eberbach Monastery in the Rheingau. 2007, p. 17.

- ↑ Wolfgang Einsingbach, Wolfgang Riedel: Eberbach Monastery in the Rheingau. 2007, p. 17.

- ^ Volkhard Huth: Visionaries in Eberbach . In: Nassau Annals . tape 114 . Verlag des Verein für Nassau antiquity and historical research, 2003, ISSN 0077-2887 , p. 37-46 .

- ↑ Bruno Krings: Literature review Nigel F. Palmer: Cistercians and their books . In: Nassau Annals . tape 110 . Verlag des Verein für Nassau antiquity and historical research, 1999, ISSN 0077-2887 , p. 512-513 .

- ↑ Werner Rösener: The conversations of the Cistercians . In: Nassau Annals . tape 111 . Verlag des Verein für Nassau antiquity and historical research, 2000, ISSN 0077-2887 , p. 13-27 .

- ^ Johannes Schweitzer, Peter Paul Schweizer: Stegwert and bridge at St. Wendelin in Niederhadamar. Hessian Road Administration, Weilburg 1983.

- ^ Hellmuth Gensicke : Landesgeschichte des Westerwaldes . 3. Edition. Historical Commission for Nassau, Wiesbaden 1999, ISBN 3-922244-80-7 , p. 121 f., 285-289 .

- ↑ Cf. Karl Rossel (Ed.): Document book of the Eberbach Abbey in the Rheingau. Volume 1. Wiesbaden 1862, p. 44.

- ^ Otto Volk: Economy and society on the Middle Rhine from the 12th to the 16th century . Historical Commission for Nassau, Wiesbaden 1998, ISBN 3-930221-03-9 .

- ↑ Otto Volk: Boppard in the Middle Ages . In: Heinz E. Missling (Ed.): Boppard. History of a city on the Middle Rhine. First volume. From the early days to the end of the electoral rule . Dausner Verlag, Boppard 1997, ISBN 3-930051-04-4 , p. 318 .

- ↑ Eberhard J. Nikitsch: DI 60, No. 82 . urn : nbn: de: 0238-di060mz08k0008209 ( inschriften.net ).

- ^ Renkhoff, Otto : Nassauische Biographie . Historical Commission for Nassau , Wiesbaden 1992, ISBN 3-922244-90-4 , p. 417-418 .

- ^ Volkhard Huth: Visionaries in Eberbach . In: Nassau Annals . tape 114 . Verlag des Verein für Nassau antiquity and historical research, 2003, ISSN 0077-2887 , p. 37-46 .

- ^ Renkhoff, Otto : Nassauische Biographie . Historical Commission for Nassau , Wiesbaden 1992, ISBN 3-922244-90-4 , p. 361 .

- ^ Volkhard Huth: Visionaries in Eberbach . In: Nassau Annals . tape 114 . Verlag des Verein für Nassau antiquity and historical research, 2003, ISSN 0077-2887 , p. 37-46 .

- ↑ Wolfgang Einsingbach, Wolfgang Riedel: Eberbach Monastery in the Rheingau. 2007, p. 20.

- ↑ The beginnings in the Tiefenthal Abbey ( Memento from February 21, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Website of the Altmünster parish in Mainz ( Memento from October 13, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Langendiebach, Main-Kinzig district. Historical local dictionary for Hesse (as of July 26, 2013). In: Landesgeschichtliches Informationssystem Hessen (LAGIS). Hessian State Office for Historical Cultural Studies (HLGL), accessed on June 26, 2013 .

- ^ Mosbach, City of Wiesbaden. Historical local dictionary for Hesse (as of July 26, 2013). In: Landesgeschichtliches Informationssystem Hessen (LAGIS). Hessian State Office for Historical Cultural Studies (HLGL), accessed on June 26, 2013 .

- ↑ Wolfgang Einsingbach, Wolfgang Riedel: Eberbach Monastery in the Rheingau. 2007, pp. 20, 48 f.