Historical viticulture and wine trade in Cologne

In Cologne , wine growing and wine trading were already practiced in the past . At the time of the Hanseatic League , between the middle of the 12th century and the middle of the 17th century, trade in the city that had become a transshipment point (Cologne received stacking rights in 1259 ), now also with imports ( Upper Rhine and Alsace ), reached its heyday. Exports went from Cologne to the Netherlands to England and the entire Baltic Sea region.

history

Cultivation in the south of the city

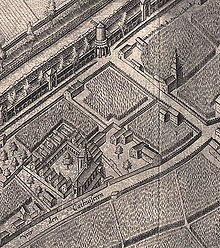

Medieval city views such as the Cologne plan drawn up by Arnold Mercator in 1571, or half a century later the drawing of the St. Pantaleon monastery by “Stengelius” show considerable vineyards within the fortified city. The labor-intensive viticulture was predominantly carried out on the numerous monastery estates, mostly given as fiefs or leases , in the south-western area of the city. In fertile years, the town's vineyards are said to have produced a yield of approximately 10,000 ohms (one ohm = 140–150 liters).

In the imperial city of Cologne, viticulture took a more important position than vegetable and arable farming. Since this culture was the most profitable branch of business, a supraregional sales market developed as early as the High Middle Ages . Wine had become the everyday drink of the entire population.

Water and wine

The poor supply of drinking water in the city also contributed to this development. The formerly exemplary water supply system of the Roman era in the CCAA had long since fallen into disrepair, and the Rhine, which was used for waste disposal, had become unusable for the extraction of drinking water. In addition to the few streams that reached the city, wells (Pütze), near which there were often latrines , had taken on this task. The sewage disposal had also been neglected. There were only a few channels (aducht, aduct) through which rubbish, dirt and rubbish could be discharged. The number of “puddles” in which the foul-smelling sewage and other litter from the alleys collected was high, and this impaired the groundwater . Many of these swampy ponds formed in the trenches in front of the former Roman city walls. For example, the Perlengraben and the old ditch (Eintrachtstraße), the large swamp behind today's Weidenbach, the Pfuhl on the Schnurgasse near "Schallenbergs Weingarten", the Pfuhl im Laach (= lacus), the Rinkenpfuhl, the Entenpfuhl, the Perlenpfuhl or the pool at the end of Tieboldsgasse. The wine thus served a good purpose, although by today's standards of rather inferior quality (it was also called "Soore Hungk"), in that it had a germ-reducing effect when mixed with water .

Archaeological evidence

During the preparatory work for a new building project on the Carthusian Wall, on a site that has been used as a Telekom depot since the post-war period , excavations were the first to provide archaeological evidence of medieval viticulture within the city. On the site, a former vineyard of the Carthusian below the Ulrepforte , archaeologists brought the Cologne Bodendenkmalpflege during excavations in the spring of 2008 relics of earlier winemaking to light. An employee of the Roman-Germanic Museum highlighted the rarity of finding such an inner-city vineyard.

A parceled trench system was uncovered, the roughly 30 centimeter wide furrows running parallel to a larger trench at a distance of about 1.20 meters. The beds in between were originally planted with vines . The area was owned by the Carthusian monastery until the French era . A stone tablet that was also recovered showed that in 1556 the Charterhouse had leased a winery along with a house, stables, wine press and garden as well as three acres of vineyards for 29 guilders.

Vinum Rubellum

Higher temperatures between the 9th and 14th centuries, the period known today as the Medieval Warm Period, contributed to the fact that viniculture could also be profitable in Cologne . Much of the land within the city was planted with vines. From documents of the parish archive of St. Mauritius it can be seen that even one acre of vineyards in Hemmersbach ( Hemmersbach Castle ) was cultivated. The growth in Cologne, mostly red wine ("vinum rubellum"), was of mediocre quality, but monitored by the council, and it was a pure and affordable drink. Just as the early "law enforcement officers" of the city took action against incorrect measurements and weights, a council decree in 1343 also made the sale of "rotten and mixed wine" a high penalty.

Monastic viticulture

Carthusian

The Archbishop of Cologne, Walram , founded the Carthusian monastery in the south-western suburb below the Ulrepforte in 1334 . After the cathedral monastery at the end of the 16th century, the cultivated vine fields of the monastery ranked second in terms of cultivation and trade in comparison to other producers. The numerous possessions of the Cologne Order, which had become wealthy over time, also outside the city, were widely scattered and stretched from the foothills to the Netherlands .

Benedictine monastery

The St. Pantaleon Abbey (villa s. Pantaleonis) in the south-western suburb, with its stately buildings, was the starting point for a later district. With its extensive orchards and vegetable gardens, as well as extensive vineyards, it and the other residents were supplied with sufficient water by the Hürther Bach . The abbey lands, which were predominantly covered with vines , extended over the area between the Weidenbach, the Gerberbach and the “Walengasse” (today Waisenhausgasse) and the Perlengraben. South of the abbey, in the vine-covered “Martinsfeld”, was the hospital of the “Quirinus Konventes”, at that time one of the oldest hospitals in Cologne.

Weidenbach Monastery

The “Kloster Weidenbach” founded in 1402 by the “Brothers of Common Life” was opposite the St. Pantaleon Abbey. The little Michaelstrasse on the Weidenbach is a reminder of the monastery named after the patronage of St. Michael . It was repealed in 1793.

Discalced Carmelites

The first monks of the “ Discalced Carmelites ” came to Cologne around 1614. Between 1620 and 1628 they built a monastery and a church dedicated to Saints Joseph and Theresa (destroyed in the last World War) on the “zum Dau” farm . In 1632 the “Discalced Carmelite Sisters”, who came from the Netherlands on the advice of their Cologne friars, acquired parcels in the “Martinsfelde”, in the middle of vineyards, and built their St. Mary of Peace Monastery there on Schnurgasse.

Augustinian women

The monastery of the white women on the Blaubach, a convent of the Augustinian women “St. Maria Magdalena ” existed from 1227 to 1802. It developed into a place of pilgrimage because of the relics venerated there .

A document from the year 1349 shows an example of properties outside Cologne, so it says: “Prior and convent of the Augustinian monastery in Cologne sell the tithe of fields and vineyards bequeathed to them by Alheidis Doys in front of Bonn, feeble von Dietkirchen, the chapter of S. Aposteln. D. anno d. MCCC quadragesimo nono, in octava b. Stephani prothomartyris ”.

Benedictine convent

The Benedictine convent at St. Mauritius was founded around 1135 and was subordinate to the Abbot of St. Pantaleon. Apart from the monastery on the northern part of the Mauritiussteinweg, there was initially only the St. Mauritius church with a rectory and a gardener's house in the corridor lined with vines.

A chronicle

In a chronicle of the Benedictine nuns from the 14th century there are notes with various comments:

"In the year of our Lord":

- 1330, then the good wine had grown

- In 1333, a quart of wine was worth an egg, and the best for two hellers and was called the wet Ludewig

- In 1351 the summer was so hot that the wine and all fruit bloomed in half of May

- 1357, the wine was so hard that it was kicked with Larsen (heavy boots) and it was called Leffelwein

- In 1368, a comet with a long tail was seen fasting; in the same year a Malter Korn was worth nine marks, a Malter wheat ten marks and a quart of wine an old groschen

- In 1386, so much wine grew that a load of wine could be sold for four guilders and a barrel for three guilders, and whoever brought his own barrel for one gulden was filled.

The vineyards of the abbey, the Mauritius monastery garden and the pastor's garden achieved an average yield of 5 to 6 ohms .

Wine trade

The merchants

Since the wine trade , but also the cultivation in the Hanseatic city and the region was an essential branch of business, Cologne was also called the " Hanseatic Wine House ". Ships loaded with wine barrels transported the coveted goods to northern countries on behalf of Cologne merchants. Gerhard Unmaze (Gerardus theolonarius) a member of the highly respected families of the early Cologne upper class, for example, as a long-distance trade merchant and customs master of the city, maintained good relationships with the commercial and financial world of England and was even able to obtain customs privileges (wine export etc.) for the city of Cologne.

Wine school

The flourishing wine business was also evident in the cityscape. A large number of wine bars and wine cellars had established themselves in the merchants' quarter and the surrounding markets (the area of the former Rhine island). Citizens who were members of the so-called wine school were allowed to pour wine in their private houses and indicated their willingness to do so by means of a Maie attached to the front door (see Strausswirtschaft ). The wine school was a municipal institution and was responsible for all matters relating to wine. So it was also the supervisory authority and at the same time the tax authority, which set the excise duties, it also awarded the bar concessions and placed workers. The wine also gave rise to the trade of cooper and cooper, the number of whom increased to such an extent that they united in a guild and later became one of the Cologne gaffs .

The clergy

In 1369 the two mayors Gir von Kovelshoven and Richolf Grin von Wichterich sparked the so-called "bottle war" with the Cologne clergy because of the wine excise . The city tried to ban the previously tax-free "Weinzapf" in the monasteries and the monastery immunities. The conflict with the clergy intensified when the mayors forcibly stopped the sale of bottles and confiscated large quantities of wine from the cathedral monastery. The council rejected the canons 'protests and underlined the legitimacy of the mayors' actions. The conflict was exacerbated by the council's request that city overseers guard the Shrine of the Three Kings in the cathedral . Because of these measures taken by the city, which were perceived as reprisals , the clergy turned to their administrator of the diocese, the administrator of the Archbishopric of Cologne, Archbishop Kuno of Trier , with the request to impose an interdict on the city . Since the clergy were still unwilling to pay the required wine taxes and all further negotiations failed, the priests were forced to leave the city. Archbishop Kuno accepted the request and imposed the interdict. It was not lifted until the summer of 1370, after the council reluctantly confirmed the tax exemption of the clergy.

The Cologne Vogt , the archbishop's representative at the court, was apparently also involved in wine shops. In a document dated February 7, 1391 it says: "Gumprecht von Alphen, Vogt of Cologne confesses that Duke Wilhelm von Berg owes eight loads of wine and 250 malter oats and that he does not want to act against his subjects before he has paid off his debt." .

The Cologne clergy brought two million liters of their own and bought wine into the city in 1712. The entire clergy was still exempt from taxes on the serving of their own wine, grown inside and outside the monasteries and monasteries. A part of the wine going on the market was also not subject to taxes.

Council wine

As a representative of the citizens, the Council Concordatum decided in 1406 quo supra feria quinta post assumptionis beate Marie to build the town hall tower . In the turn, the new urban symbol of bourgeois power, was also:

A "Kelre zo der Stede Weynen" (wine cellar).

This new cellar was used by the councilors as a wine depot for special purposes. Officials received a so-called wine or presence mark, which corresponded to a certain monetary value, as an additional salary supplement when proof of attendance was provided, and could thus have a quantity of wine given to them corresponding to the mark value. Another form of the council wine, on the other hand, was revived in 1981 by the district president of Cologne, Franz-Josef Antwerpes . He planted some vines in front of the Cologne regional council that he had received as a gift from a winegrowers' cooperative in the Ahr. He had their grapes processed into wine from 1984 onwards, heralding a small renaissance in Cologne wine-growing. In 2012, the vines were removed by his successor due to renovation work, which brought the renaissance to an end again.

Literature / sources

- Adam Wrede : New Cologne vocabulary . 3 volumes A - Z, Greven Verlag, Cologne, 9th edition 1984, ISBN 3-7743-0155-7 .

- Thomas, Adolph: History of the parish St. Mauritius in Cologne. With an illustration of the old Abbey of St. Pantaleon after Stengelius. 1st edition JP Bachem, Cologne 1878.

- Sonja Zöller: Emperor, businessman and the power of money. Gerhard Unmaze of Cologne as financier of the imperial politics and the "good Gerhard" of Rudolf von Ems . (= Research on older German literature; 16). Wilhelm Fink Verlag, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-7705-2850-6 digitized .

- Carl Dietmar: Die Chronik Kölns , Chronik Verlag, Dortmund 1991, ISBN 3-611-00193-7 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b After Carl Dietmar, in: Kölner Stadt Anzeiger, edition of March 4, 2008

- ↑ Adam Wrede, Volume III. P. 284

- ^ Adolf Thomas, reference to Ennen and Eckertz, Urk. IV, p. 295

- ^ Leonard Ennen, History of the City of Cologne, I., p. 682

- ^ Carl Dietmar: Die Chronik Kölns , p. 116

- ↑ Adam Wrede, page 125, volume I., Hof zum Dau, the "her Melchior von Mulhem, rentmeister"

- ↑ Online archive finding aid U 1/193 in the Historical Archive of Cologne

- ↑ Adolf Thomas, reference to Annalen des Ver. for low rh. Business Issue 23, p. 46 ff.

- ↑ Sonja Zöller

- ^ Adan Wrede, Volume III. P. 284

- ↑ Carl Dietmar, p. 119

- ↑ Online Findbuch Archive NRW No. 745, with reference to: Th. J. Lacomblet, Urkundenbuch III, 949 Note 2.

- ↑ Carl Dietmar, p. 203

- ^ Adam Wrede, Volume II, p. 369

- ^ Chronicle of Cologne, p. 132

- ↑ Carl Dietmar, p. 202

- ^ Antwerp's regional council mourns the loss of its vines, Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger