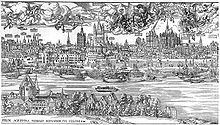

Cologne city view from 1570

The Cologne cityscape from 1570 (so-called Mercator plan ) is a map of Cologne drawn up by cartographer Arnold Mercator in 1570 , which shows the ancient interest and the antiquarian collecting activity of the patriciate.

First views of the city of Cologne

One of the earliest bird's-eye views of European cities is the portrayal of the martyrdom of St. Ursula of Cologne , which shows Holy Cologne. The master of the little passion tried here in a canvas picture to place the churches of the walled city from a high point of view in a central perspective. Within the city, almost only churches are depicted, so that it is a realistic image of the city. The artist's intention was not to depict a cartographic representation, but to depict the symbol of a “city of God”. The painting was created in 1411 and is shown today in the Wallraf-Richartz Museum in Cologne . Werner Rolevinck published the first printed view of Cologne around 1479 with his Fasciculus temporum ("Assembly of Times"). A variant of this can be found in the Koelhoff Chronicle in 1499 .

The monumental Cologne cityscape from 1531 by Anton Woensam occupies a prominent position . He had presented a 0.62 × 3.43 meter wide city prospectus ("The Great View of Cologne") and thus created one of the largest European city prospectuses at all. This was intended as a present for Emperor Ferdinand I and was presented to him when he was elected on January 5, 1531 in the choir of the otherwise unfinished Cologne Cathedral , which was completed and consecrated in 1322 . Woensam looked across the Rhine from the east and showed Cologne on the left bank of the Rhine in profile. Woensam's woodcut even reveals details of the window and facade design.

According to the depiction of Venice from 1500, it was considered to be one of the first true-to-life and detailed city brochures in Germany based on the Augsburg bird's eye view plan by Georg Seld from 1521. Other early woodcut brochures from that time for cities like Duisburg (1564) meant progress, but remained front views and did not yet offer a spatial view of things. Gerhard Mercator , Arnold's father, was probably the one who significantly integrated the mathematics into the representations, which were then also reflected in the work of his son.

Mercator's drawing and engraving

prehistory

After an increasing number of Protestant refugees from the Netherlands migrated to the free imperial city of Cologne from 1565, the city council felt compelled to get to know the current population situation in its urban area better. On December 2, 1569, the council received a warning from the Netherlands not to accept or tolerate refugees. This was followed by an edict of the city council on July 23, 1570 , according to which all foreigners who had been living in the city for four years had to prove that they had left their homeland with the approval of their authorities. At that time the city had around 40,000 inhabitants and around 8,000 houses. The cartographer Arnold Mercator, eldest son of the famous cosmographer Gerhard Mercator, who, among other things , had developed the Mercator projection , received the order for cartography from the Cologne City Council. He had been doing surveying work for the Diocese of Trier since 1567 .

drawing

Arnold Mercator stayed in Cologne in 1569 to prepare his bird's eye view plan and carried out his own surveys , adding to the short series of renaissance survey campaigns of individual cities. After transferring individual data and sketches to a large-format drawing on paper, he handed the work over to his municipal clients in 1570. He made an ink drawing, which he presented to the city council by September 1570. On September 11, 1570, he made the assessment of the floor plan of Cologne a requirement for the two tuning masters. In the minutes of the council it says literally: "Arnoldi Mercatoris abcontrafeitung der Stadt Cöln, and what he presents before work can be seen at both stigmeisteren zo and filled with a council zo brengen." With the help of this map, the city council managed to control the accommodation of the immigrants.

Copper engraving

The cartographer used his drawing as the basis for the most famous copperplate engraving , which he completed on his birthday on August 31, 1571 and whose dimensions of 1.08 × 1.71 meters he distributed over 16 plates. In doing so, it stood out from other typifying and idealizing cityscapes of that time and stuck to reality. While the watercolor hand drawing was still dedicated to the city senate, the copper engraving was dedicated to the Archbishop of Cologne, Salentin von Isenburg , whose coat of arms has now replaced the city's coat of arms. Mercator published the engravings on his own account.

Equipped with a print privilege from Emperor Maximilian , Mercator decided to publish the Cologne plan on his own account. For reproduction, he used the further development of the previously common method of woodcut , the emerging technique of copper engraving. In his father's business in which the members of the family were even printers, engravers and cartographers created 16 carefully prepared thin copper plates of different formats, with fine with a stylus incorporated engravings were provided. These then served the print he made on sixteen sheets. The copies of the Cologne cityscape created in 1570/1571 were a novelty at that time due to their complex information content and the accuracy of the cartographic reproduction. Over a long period of time, they served as a model for later Cologne city maps.

Iconographic interpretation

Arnold Mercator provided the first known city map-like representation on the basis of geometric criteria that suggests a bird's eye view. The drawing is a representation of the city of Cologne in ink on parchment in the form of a city map. In the lateral marginal strips he particularly depicted Roman inscriptions. Mercator's drawing, executed in watercolors, formed the first masterfully designed city map of Cologne. In doing so, he took into account 169 information on the location, including all 18 parishes, and tried to match and describe it accurately in his cartographic and scientific representation (“exactissime descripta”). The large scale of around 1: 2450 enabled him to take into account details, such as the Schützenhof ("Schutten hoff") with four lanes on the northeast corner of Neumarkt , which the city had set up shortly before 1450. The drawing is a mixture of a bird's eye view and elevation technique and visualizes the semicircular shape of the city open towards the Rhine. It gives posterity information about medieval street names and courses, important buildings and their state of construction at that time. The trapezoidal shape of the Roman town and the suburb of the Rhine around the Heumarkt, which was annexed in the 10th century, are recognizable . By using isometrics , Mercator even allows a view of the floor plans and, in some cases, the front of buildings, which, however, make the streets appear wider.

The drawing can rather be characterized as a city map , in which the facades of the buildings are folded up in perspective. The plan refers to the imperial printing privilege and names Duisburg as the place of publication. According to Josef Benzing (1951), the maps and the associated index of place names were printed by Gottfried von Kempen in Cologne. Only three printed copies are known today, which are in the possession of the Royal Library of Stockholm , the Duchess Anna Amalia Library in Weimar and the collection of the Kreissparkasse Cologne . The hand drawing belongs to the holdings of the Historical Archive of the City of Cologne and was kept there until its collapse on March 3, 2009. However, it had been in an extremely desolate condition since 1876 at the latest, because it had been buried for a long time under the rubble of a ceiling that had fallen down due to rain.

In addition to the shrine books , Mercator's work is the most important source of names for historians, especially for the street names he used . It offers both the opportunity to gain an insight into the Cologne cityscape of the 16th century and to localize the depicted buildings with the help of georeferencing .

- Excerpts from the cityscape from 1571

Between "Breide straiß" ( Breite Straße ) and "klocker gaß" ( Glockengasse )

Details of the Cologne cityscape

Wherever it seemed advisable to Mercator, he put cartouches in the border of his work , in which pictures and texts were given on important details of the city map, which he marked with numbers or letters. In addition to the information on the contemporary naming of the precisely reproduced streets, additional symbolic signs explained the location of often repeating objects in the urban area, such as the course of the Roman city wall. Mercator drew the city wall and its gates in great detail, as well as the numerous churches, chapels and monasteries at the time. As with the fortifications , he meticulously recorded the floors of all buildings, details such as roofs, gables, windows, bay windows , stair towers , inner-city gates, the course of streams with their bridges and footbridges , as well as fountains and cattle troughs. His drawings reflected the density of the settlement and showed the agricultural areas of the city. Mercator also documented life on and around the Rhine . He showed the then still existing Rhine islands , the shipping of this time in various forms, anchored Rhine mills and the quays of the city with cranes, carts and busy people.

Integration of the urban history

Mercator mainly decorated the border of his city drawing with objects that, like the altar of Victoria, referred to the city's Roman past, and called them "antiquitates Coloniae" or "antiquitates territorii Coloniensis" to refer to the Cologne site. An Old High German inscription in Cologne Cathedral, which he attributed to the Germanic era, he called "inscriptio vandalica", which he used contemporary terminology. With the exception of four illustrations, experts were able to classify and assign all of the monuments drawn by Mercator as works from the 1st to 4th centuries based on local sites.

Design of the plan

The accompanying book published in the catalog of the Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn for the exhibition 2010 contains an illustration of a copy in the possession of the “National Library of Sweden”. The dimensions of this copperplate are 122 × 185 cm. The title line of the stitch reads:

- COLONIA AGRIPPINA ANNO DOMINI MD L XXI. EXACTISSIME DESCRIPTA

According to the archaeologist Noelke , the dimensions of the preserved copies of the cityscape , as far as recognizable (only the image and text of the print should be in good condition), match the original. With the words "exactissime descripta" contained in the inscription on the title bar, Mercator probably wanted to refer to the accuracy of his work. A total of forty-eight objects had been drawn in by Mercator in the two lateral margins of the plans, with the number of twenty-eight stone monuments mostly containing inscriptions (sometimes only fragmentary, according to reality) being dominant. Depending on their dimensions, he placed all the objects individually, in pairs or, as with smaller clay pots , as an ensemble . The lower picture border of the plan ends with a decorative strip without any further decorative details.

Notes on text and image additions

In addition to the actual cityscape, the marginal drawings and the texts that are partially contained in them are very informative. Mercator's client was the council, but he added the coat of arms of the incumbent Prince and Archbishop Salentin von Isenburg in a prominent place . The image of a ruler in double steps ( mille passus ) referred to his precise surveying work. In a longer text execution below the upper right edge of the picture, which he with

- DE FVNDATIONE ATQVE ANTIQVITATE HVIVS VRBIS

titled, he explained the founding and further development of the city at the time. He also filled the various cartridges contained in the plan margin with additional information. Some owners of the antiquities he portrayed were named by him in these. They were all gentlemen from the global or ecclesiastical upper class, such as the mayor of the city (Consul) Konstantin von Lyskirchen , the licentiate of law, councilor and imperial mint master Johann Helman, the professor of jurisprudence at the University of Cologne Johann Rinck , the electoral prince Councilor Johannes Broich. Further monuments of the city are said to have been in the property of church dignitaries, of which "Noelke" cites that of a canon of St. Gereon and the house of the provost and in this case refers to Hermann von Neuenahr .

Whereabouts

Little is known about the whereabouts of the previously completed edition, as well as that of the printing plates. Johann Jakob Merlo , who published in the 19th century, cited a council report in a treatise which dealt with the original of the Cologne cityscape from 1570, for which a dimension of 109 × 170 cm was given. In this context, the “Helmannschen” and the Hardenrathschen stone collections were cited, and with regard to the plan there was talk of a “very damaged hand-drawn drawing on parchment ”. However, this statement is contradicted by the fact that neither in other sources, nor in the most recent treatise "Noelkes", the term parchment is used. Whether the original of the municipal archive mentioned by Merlo is still preserved is questionable due to the loss of extensive archive holdings due to the accident in 2009.

See also

literature

- Peter Noelke: Discovery of History, Arnold Mercator's city view of Cologne . In: Renaissance am Rhein, catalog for the exhibition in the LVR-Landesmuseum Bonn, 2010/2011 . Hatje Cantz publishing house, ISBN 978-3-7757-2707-5 .

- Peter Noelke: The beginnings of the Cologne antiquity collections and studies in humanism . In: Stephan Hoppe, Alexander Markschies, Norbert Nussbaum (eds.): Cities, Courtyards and Culture Transfer. Studies on the Renaissance on the Rhine. Regensburg 2010, pp. 30-65.

- Paul Clemen: The art monuments of the Rhine Province on behalf of the Provincial Association , hrg. by Paul Clemen, Volume VI, I. and II. Department The Art Monuments of the City of Cologne . First section: Sources, first section sources, second section: Roman Cologne, Düsseldorf, printing and publishing house L. Schwann, 1906.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Picture of the week ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Lutz Philipp Günther, The pictorial representation of German cities , 2009, p. 42.

- ↑ a b Peter Fuchs (Ed.), The Chronicle of the History of the City of Cologne , Volume 2, p. 61 f.

- ↑ Hoppe, Stephan: The measured city. Small-scale survey campaigns in central Europe in the 16th century and their functional context . In: Baumgärtner, Ingrid (Ed.): Princely coordinates. Land surveying and rulership visualization around 1600 (writings on Saxon history and folklore 46). Leipzig 2014, pp. 251–273, on the Mercator plan p. 269 full text on ART doc .

- ↑ a b c d e Peter Noelke: Discovery of History, Arnold Mercator's City View of Cologne , p. 251.

- ^ Hugo Borger / Frank Günter Zehnder, Cologne: the city as a work of art , 1982, p. 44.

- ↑ Before 1603, those in the rank of reigning tuning masters were called stabbing masters because they were the decisive factor in the equality of votes in the senate. ( Friedrich Ev. Von Mering and Ludwig Reichert: On the history of the city of Cologne on the Rhine, Cologne 1838, p. 214 in the Google book search)

- ↑ Herbert van Uffelen, Bevestigend samenleven , 1987, p. 152.

- ↑ a b Yvonne Leiverkus, Cologne: Pictures of a Late Medieval City , 2005, p. 25 f.

- ↑ Hans Wolff, 400 Years of Mercator, 400 Years of Atlas , 1995, p. 31.

- ^ Monthly for the history of West Germany, Volume 2, 1876, p. 593.

- ^ Archives of the City of Cologne; s. ibid. 25, f. 308b, 1570 Sept. 11. Cf. MERLO Sp. 588. In: Paul Clemen, Die Kunstdenkmäler der Stadt Köln B. VI, p. 90.