Koelhoff's Chronicle

Koelhoffsche Chronicle is the name of Johann Koelhoff the younger native chronicle of the city of Cologne from the year 1499th

preparation

Johann Koelhoff the Younger took over his father Johann Koelhoff the Elder's office in July 1493 at the latest , but without ever achieving his father's publishing achievements. However, a work that was significant in terms of typography and content made the son famous for all time - the so-called Koelhoff Chronicle named after him . The main bases for this work were in particular Gottfried Hagen's rhyme chronicle of the city of Cologne from 1270 and the first universal historical city chronicle Agrippina by Heinrich van Beeck , published in 1472 , in which he described the work of the archbishop. The preparatory work for Koelhoff's Chronicle began as early as 1494 and probably brought Koehlhoff into great financial difficulties because it was based on a publisher's miscalculation. In the preparatory phase, the sale of the Ryle in der Hellen house, which had only been acquired in 1496, fell on March 22nd, 1499, and from then on the Koehlhoffs could only use it as a rental shop. The chronicle even seems to have driven Koehlhoff's business to ruin, because his printing work stopped after about 6 years.

publication

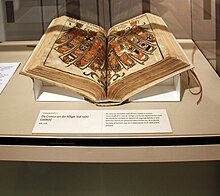

On August 23, 1499 Koelhoff published his 355 double-sided sheets, Die Cronica van der hilliger Stat Coellen, in the format 25.6 × 34.4 cm. It contained 368 colored woodcuts from 45 wooden sticks, 12 of which were almost or completely the size of a sheet and one was the size of a double sheet. The annalistic level plant used as his model further, the world chronicle Hartmann Schedel , woodcuts for text illustration. It is considered to be the first printed product in Cologne's city history, published in a small print run of around 250 copies. The news it contains about the city of Cologne from the middle of the 15th century is considered to be halfway reliable. The author of this typographically masterfully designed and universally historically oriented city chronicle is unknown; it is probably the schoolmaster Johann Stump from Rheinbach. The author of the chronicle criticizes both the clergy and secular authorities, so that the work was banned and confiscated three months after its publication. At the instigation of the church, some pages had to be exchanged. The Koehlhoffsche Chronicle published in 1499 simultaneously at the peak and the end of the late medieval history of the city.

content

Koelhoffsche Chronik - Marsilius in the fight against the Romans at the gates of Cologne

Koelhoff Chronicle - Battle of Worringen

In a compilation of various text sources, the chronicle reports on a large number of initially worldwide and then only Cologne events and integrates the history of Cologne into a universal historical framework that begins with creation (“scheppunge”). It begins with the creation of Eve up to her expulsion from paradise (sheet 7). The topic related to Cologne's history begins with the foundation of Cologne in page 30. The work is structured according to emperors, bishops and popes, almost all of whom are presented. A woodcut (sheet 58) shows the Roman Emperor Trajan under a canopy, with the Cologne coat of arms on his right . Its three crowns symbolize the Three Kings , whose bones the city housed. The eleven flames represent the 11,000 virgins ("ionfferen") who are said to have been killed by the Huns at the side of St. Ursula of Cologne on her return from a pilgrimage to Rome in 452 and died as a martyr. The 15 old Cologne patrician families are listed in front of the throne of Emperor Trajan . This woodcut symbolizes a legend that has been solidifying in Cologne since the 13th century, according to which the Cologne patriciate derives its origin from 15 families recruited from high Roman nobility. These are said to have been sent to Cologne by Emperor Trajan with exemption from tributes in order to entrust them to rule over the city. From sheet 59 onwards there are several woodcuts about the Cologne gender coats of arms , from sheet 136 onwards he presents the guild coat of arms .

Koehlhoff consolidates the legend of the founding of the Church of St. Gereon by St. Helena ; the mother of Constantine the Great had actually built numerous churches. Since Helena died around 330 long before construction began on the church at the end of the 3rd century, this legend is historically untenable. A woodcut from 1265 shows the Weyertor with the army of Archbishop Engelbert II. Von Falkenburg besieging the city of Cologne . In September 1265 one of the besiegers, the Count of Kleve , dreamed "that the walls of the city were occupied by the saints" and it therefore seemed impossible to defeat the Cologne residents. The battle of Worringen in 1288, in which the flag wagon of Archbishop Siegfried von Westerburg with the key to the city of Cologne is said to be shown, is also discussed. The “wagon with key” shown in the picture of the chronicle is not the archbishop's flag wagon, but the wagon of the citizens of Cologne, that is, of his opponents. For the first time ever, the Chronicle reports on the death of Johannes Duns Scotus on November 8, 1308, referring to the memorial on the grave of the scholar in the Minorite Church in Cologne . In 1437 the cathedral towers had reached a height of 59 meters (sheet 176). In the portrayal of Archbishop Wilhelm von Gennep it is confirmed that Maternus was the first Archbishop of Cologne. In the very extensive description of the Cologne weavers' uprising from page 274, the chronicle - of several alternatives - incorrectly defines the street fight that ended the battle at the end of 1371, but November 20, 1372 actually applies. On sheet 286 she takes up - as the earliest evidence ever - the Richmodis saga , "like a vrawe tzo Coellen who died and buried something and was neither dug up, was alive". In the later - to this day - much-cited chapter on the invention of the printing press ("Van der boychdrucker kunst"; sheet 311/312) the author writes that Mainz was the city of the first printing, "wiewail die kunst is vonden tzo Mentz, als vorrß Is, up the white is used as a common word, so is the first vurbyldung from the in Hollant uyss the Donaten, which is printed synonymous with the tzijt ”. In doing so, he relativized the merits of Johannes Gutenberg , referring to the Cologne first printer Ulrich Zell . The chronicle was finally indignant about a professional relic theft from the St. Vincent chapel in the parish church of St. Laurence in December 1462, whereby the head of St. Vincenz was stolen by the Swiss relic robber Johannes Bäli ("heuft by a paffen overmitz a subtle anslach") and over made the detour to Rome on May 25, 1463 in the Bern Minster . On August 27, 1463, the city council of Cologne complained in vain about this in Bern - St. Vincent became the city patron of Bern. One of the last events in the Chronicle dates back to February 5, 1498, when the blind killed a pig in the Alter Markt .

Reception and whereabouts

Koehlhoff's Chronicle of the City of Cologne is one of the most compact universal historical works of the late Middle Ages. The largest part of the text is not one of the primary sources, but there was no such comprehensive work on the city's history before. It takes 277 verses literally from Hagen's “Rhyme Chronicle” and is therefore classified as a prose resolution in parts. The chronicle also used van Beeck's “Agrippina” as a source for long stretches. Up to the year 1445 the compilation mostly followed the sources verbatim, patriotically glorified Cologne's values in the old Cologne dialect and did not spare clerical criticism; for the archbishop was endowed with great powers, since he combined the rights of a secular ruler and a high church prince. The work exerted a strong influence on the historical literature of the 16th century, which in many ways corresponds literally with him. Along with the work “The Origin and Beginning of the City of Augsburg”, it is the only historiography that found its way into the printing press during the incunable period . Around 1530, the chronicle was combined into a “cleinen kronica” and all components not related to Cologne were shortened. “The common stylistic features of the woodcuts indicate that they are all illustrated by Cologne residents, which is likely to be further corroborated by the numerous authentic views of the city.” The chronicle takes first place in the poor history of the old imperial city of Cologne.

A copy of the city chronicle is in the Herzog August Library in Wolfenbüttel and was digitized there. The historical archive of the city of Cologne , the Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn and the Rheinische Bildarchiv also have other editions. Of the approximately 150 surviving copies, a maximum of 20 are privately owned, with prices of up to 38,000 euros.

literature

- Volker Henn : On the world and history of the unknown author of the Koelhoff Chronicle , in: Rheinische Vierteljahrsblätter 51 (1987), pp. 224–249

Web links

- Cronica van der hilliger Stat van Coellen in the repertory "Historical Sources of the German Middle Ages"

- Koelhoff's chronicle in the general catalog of incandescent prints (GW number GW06688)

- Wolfenbüttel Digital Library (WDB): Herzog August Library, digitized book version

Remarks

- ↑ Ursula Geisselbrecht-Capecki, Der Niederrhein: Drawings and Books from the Robert Angerhausen Collection , 1993, p. 66

- ↑ Christoph Reske, The Book Printers of the 16th and 17th Centuries in the German Language Area , 2007, p. 424

- ↑ Eberhard Isenmann, Die deutsche Stadt im Mittelalter 1150-1550 , 2014, p. 444

- ↑ Hubertus Menke / Robert Peters / Horst Pütz / Ulrich Weber, Vulpis adulatio , 2001, p. 660

- ^ GG Saur Verlag & Co., travel reports and historical poetry , 2011, p. 75

- ^ Johann Jakob Merlo, General German Biography , Volume 16, 1882, p. 419 f.

- ↑ Ernst Voltmer , Medieval Standarten und Fahnenwagen , in: Die Blätter für deutsche Landesgeschichte, Volume 124, 1988, pp. 187-209

- ^ Andreas Speer / David Werner, 1308: Eine Topografie historical Simultaneousness , 2010, p. 463

- ↑ how a deceased woman from Cologne was buried, dug up again and lived again

- ↑ Although the art as it is now practiced was invented in Mainz, its first preparatory training was invented in Holland, where Donate had already been printed. Only from this did the finer art of the later period develop

- ↑ Heinrich Meisner / Johannes Luther, The Invention of Book Printing , 2012, pp. 45 ff.

- ^ Joseph Emil Nünlist, The Middle Ages Bern: His Religious and Church Relationships , 1936, p. 44

- ↑ Christine Stöllinger-Löser, Die deutsche Literatur des Mittelalters , 1981, Sp. 385

- ↑ Christine Stöllinger-Löser, Die deutsche Literatur des Mittelalters , 1981, Sp. 694

- ↑ Brigitte Corley / Ulrike Nürnberger, painter and founder of the late Middle Ages in Cologne , 2009, p. 13

- ^ Bavarian Academy of Sciences, The Chronicles of German Cities , Volume 12, 1875, p. Ii

- ↑ 1483 printed by Johann Bämler

- ^ Leo Baer, The illustrated history books , 1903, p. 189

- ↑ Melanie Damm, Luste iudicate filii hominum: The representation of justice in art using the example of a group of pictures in the Cologne town hall , 2000, p. 128

- ↑ Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger from April 23, 2013, Cologne Chronicle with Adam and Eve ( Memento of the original from December 19, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.