Cologne weavers uprising

As Cologne Weberaufstand the bloody clashes of will guild of weavers with the political leadership of the city of Cologne from 1369 to 1371, respectively.

prehistory

In 1149, the bed-making weavers founded the first association of craftsmen , a so-called guild, in Cologne . These and other guilds organized their affairs independently. The council of the city of Cologne only intervened in their autonomy to remedy grievances. His intervention was felt to be benevolent. Anyone who wanted to practice a trade in Cologne was forced to join the guild concerned (guild compulsory). This made the guilds one of the first member bodies. However, the guilds had no part in the political life of the city and, despite their economic and social position, were not represented in the patrician council of the city of Cologne. The guilds increasingly distrusted many of the council's decisions. The city council was not accessible to ordinary people, and from the point of view of the patriciate they were not welcome here either. For the sexes, it was impossible for such common people to hold public office. Godefrit Hagene ( Gottfried Hagen ) introduced some of the new lay judges by name and with their professions: Hermann the wedge engraver, Leo the fisherman, Gerlach the weaver and others, “all small people of the artisan class” (1245–1253). Hagen said that if it weren't a sin, he would hate that holy Cologne was ruled by such "donkeys". Even if a donkey were given a lion's skin, it would always remain a donkey (here he uses a Bible parable). The weavers placed themselves at the head of all circles that were dissatisfied with the political decisions of the patrician council.

The actual weaver revolt

The uprising of the weavers' guild in Cologne can be divided into three phases: the weavers' uprising from May 20, 1369 (Pentecost) to July 2, 1370, the quiet period until November 19, 1371 and finally the bloody weavers' battle on November 20 1371.

Uprising on May 20, 1369

The noble Cologne council member Rütger Hirzelin vom Grin was accused in 1367 of embezzling city funds. This act was uncovered on January 6, 1367 with the help of the Cologne guilds, who wanted to increasingly control the political decisions. Vom Grin was executed for this on May 20, 1369 (Pentecost). A man arrested at the same time for street robbery is tried, but the weavers take this process too long; they storm the prison and cut off his head without judgment. There were further tensions with the council and ultimately resulted in the weaver revolt. Furthermore, displeasure arose because three members of the Cologne Land Peace Day were accused of having made concessions to a noblewoman (Edmund Birkelin) who were hostile to the city of Cologne and thus practicing nepotism . After these three bowed to public pressure in custody and eight other council members were asked to follow them and followed this request on January 7, 1371, the power of the guilds, especially the weavers, became abundantly clear. In the end, 8 out of 15 council members were arrested.

Quiet time

This pressure from the weavers led to a constitutional amendment. This aimed u. a. on abolishing the Richerzeche as an institution of the Meliorate, on organizing the council , which is still reserved only for the Cologne patricians, free of lay judges, on limiting the broad council, which has now been reduced to 52 members, to representatives of the craftsmen and merchants, and on assigning more extensive powers to this institution. This reorganization came into effect on July 2, 1370. The second phase of the weaver's time, between July 2, 1370 and November 20, 1371, is characterized by unilateral decisions by the new broad council. Possibly because of the inexperience in the conduct of office, perhaps out of arrogance and pride, the new large council passed resolutions that distributed the costs unevenly. This included the introduction of a wine tax excise ( consumption tax ) and a direct wealth tax ("lap"), which burdened the wine merchants on the one hand and the landowners (rich merchants and patricians) on the other, but spared the weavers who had come to power. In August 1499, Koellhoff's Chronicle criticized the fact that the council was expanded to include the weavers: “It was strange and strange to see Cologne [...] always being ruled by fifteen noble families [...] now being replaced by the weavers . "

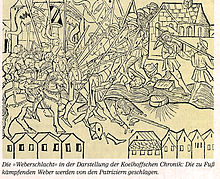

Bloody weaver battle

The intervention of two woolen weavers in the Jülich-Brabant feud, which was not permitted by the council (on August 22, 1371, the decisive battle of the feud took place near Baesweiler , in which the troops of the Duke of Jülich, supported by the Duke of Geldern, against the Duke of Brabant remained victorious) and the resulting political conflicts led to a battle on November 20, 1371 between the narrow council, the (de facto disempowered) Richerzeche and the gaffs , who no longer agreed with the weavers' policy, on the one hand and the weavers on the other other side. When the Wollenweber Henken von Turne (who had been sentenced to death as a soldier in the Jülich-Brabant feud) was forcibly snatched from the hangman, merchants and some of the guilds that did not cooperate with the weavers assembled armed to take action against the weavers fight. In front with the city flag they marched from St. Brigiden (next to Groß St. Martin ) via the Alter Markt and Heumarkt to the Malzbüchel, where the weavers gathered. The outnumbered weavers left their quarters and stood in battle order at the Waidmarkt. The bloody battle on the Greek market began, but the weavers fled realizing their inferiority. Those of the weavers who did not fall or who did not leave the city were soon tracked down and locked in the city towers. The reactionary forces severely punished the weavers, many were expelled, the convicted weaver Henken van Turne was finally beheaded in the hay market and the assets of the weavers' guild, including 25 houses, were confiscated. On November 21, 1371, the council informed the citizens that the not yet caught criminal weavers were allowed to leave the city unhindered as long as the bells of St. Mary in the Capitol were ringing. Those who had already fled were never allowed to enter the city again.

Political Consequences

The reactionary victors of the battle set up a commission of twelve people who did not belong to the narrow city council to prepare a new "oath book" (city constitution). This should bring the urban conditions back to the earlier aristocratic regiment and avoid new revolts if possible. On February 22, 1372, the close council was downsized and limited to patrician families and merchants, as it had been before the weavers' battle. The patriciate had thus survived the political upheavals of the weaver revolt. But the weavers' battle triggered the separation of the patricians who had previously cooperated into the "griffins" and the "friends", which even resulted in hostilities. On January 4, 1396, the group of "Friends" violated the "Griffins". When Constantin von Lyskirchen , leader of the "Friends", was arrested on June 18, 1396 , the era of the ruling patrician families ended for the time being.

Contemporary records

In addition to Koehlhoff's chronicle, there is also a record of the events, written as a “speech” in rhyme form, which is attributed to Heinrich von Lintorf. The Cologne city clerk reports meticulously about the occurrences of the weaver revolt, naming those involved. However, it is questionable whether he was a witness of the events, especially since he repeatedly cites oral traditions and written sources. It is at least certain that his “Weverslaicht” was created in Cologne.

literature

- Peter Fuchs: Chronicle of the history of the city of Cologne . Volume 1 and 2, Cologne 1990, ISBN 3-7743-0262-6 .

See also

- General article on the weaver revolt

Individual evidence

- ^ City of Solingen with reference to the Cologne guilds

- ↑ Edith Ennen: The European city of the Middle Ages . 1987, ISBN 3-525-01341-8 , p. 151.

- ↑ Felix Hauptmann in the magazine for the history, language and antiquities of the Middle and Lower Rhine , Volume 9, No. 4, Bonn 1909

- ^ Carl Dietmar, Werner Jung: Small illustrated history of the city of Cologne . Cologne 2002, ISBN 3-7616-1505-1 , p. 77

- ^ Peter Fuchs: Chronicle of the history of the city of Cologne . Volume 1, Cologne 1990, p. 31 ff.

- ^ Daniel Heisig: Comparison of the events of the weavers' revolt (1370) and the fall of the sexes (1396) in Cologne in the 14th century . Trier 2004.

- ^ Peter Fuchs: Chronicle of the history of the city of Cologne . Volume 1, Cologne 1990, p. 317.

- ^ Hans-Jürgen Gerhard, Karl Heinrich Kaufhold: Structure and dimension: Festschrift for Karl Heinrich Kaufhold on the 65th birthday . 1997, ISBN 3-515-07065-6 , p. 391 f. GoogleBooks

- ↑ https://www.geschichtsquellen.de/repOpus_04608.html ; Volker Honemann in: author Encyclopedia Vol. 10 (1999) ISBN 3-11-015606-7 ., Sp 780-782