John (Evangelist)

The Evangelist John , also known as Johannes Evangelista or John of the (Latin) Porte in the church tradition , is the main author of the Gospel of John . The tradition equates him with the apostle John as the favorite disciple of Jesus and sees in him also the author of the letters of John and of Revelation . In the historical-critical research , this traditional view is highly controversial. This discussion has gone down in the history of research into the Gospel of John as the “Johannine question”.

Historical evidence

The Gospel of John

In the Gospel of John, the nameless favorite disciple of Jesus is named as the author of the text:

“Peter turned and saw the disciple whom Jesus loved following (him). It was the disciple who leaned against Jesus' breast at that meal and asked him: Lord, who is it who is going to betray you? When Peter saw this disciple, he asked Jesus, Lord, what will happen to him? Jesus answered him: If I want him to stay until I come, what is it to you? But you follow me! Then the opinion spread among the brothers: That disciple does not die. But Jesus did not say to Peter: He will not die, but rather: If I want him to stay until I come, what is it to you? It is this disciple who testifies to all of this and wrote it down; and we know that his testimony is true. "

Although the final chapter of the Gospel expressly testifies to the authorship of the “favorite disciple”, there is no identification with the apostle John. In addition, a group of authors seems to be speaking here as a “we” who differs from the author of the main text, Jn 1-20. It is noticeable that in contrast to the synoptic gospels, the name of the apostle John is never mentioned in the entire Gospel of John. When “John” is written, it is always about John the Baptist . The "sons of Zebedee" - known to the Synoptics as James and John ( Mk 1.19 EU ) - only appear in 21.2 EU , but they are not named there either. It is therefore assumed that a Johannine circle , which was also responsible for adding the final chapter 21 to an already existing text, with the favorite disciple placed a figure from the most intimate proximity of Jesus as a witness and undisputed authority in the foreground. This is supported by the fact that the Gospel speaks of a “we” not only at the end in John 21:24 EU , but also in the prologue ( John 1:14, 16 EU ), which means eyewitnesses of Jesus' appearance. In any case, the Gospel of John itself points to the authority of an outstanding witness to whom the members of the Johannine congregation emphatically appeal.

Early Church Testimonies

The earliest information about the effectiveness of a disciple and apostle John outside of the New Testament can be found in the writings of Bishop Irenaeus of Lyon (around 135–202), which are also cited by the church historian Eusebius of Caesarea (around 260–337). In his youth Irenaeus was a pupil of Polycarp of Smyrna (69–155), who - so writes Irenaeus - was in turn a pupil of the apostle John. According to this early source from the end of the 2nd century, John the Apostle is also the author of the Gospel: “ Finally, John, the disciple of the Lord, who also rested on his breast, published the Gospel himself when he was in Ephesus in Asia stopped ”. Here four statements are made that have significantly shaped the Christian tradition:

- The apostle John is the favorite disciple.

- He is therefore the author of the gospel.

- The Gospel of John was published during his stay in Ephesus - that is, during his lifetime.

- It was written according to the Synoptic Gospels (“last”).

In his church history, Eusebius explains the discrepancies between the Gospel of John and the Synoptic Gospels as follows:

"After Mark and Luke had published the Gospels they preached, according to tradition, John, who had constantly occupied himself with the oral preaching of the Gospel, saw himself compelled to write it down, for the following reason: After the three Gospels that were written first had already come to the knowledge of all of them, including John, the latter accepted them, as is reported, and confirmed their truth and declared that the only thing missing from the scriptures was a representation of what Jesus first did at the beginning of his teaching activity. He was right about that explanation. For it is clear that the three Gospels recorded only what the Savior did for a single year after the imprisonment of John the Baptist, and that they also indicate this at the beginning of their accounts. [...] According to tradition, the apostle John has therefore, upon request, about the time about which the earlier evangelists were silent, as well as about the deeds of the Redeemer that occurred during this time, i.e. before the capture of the Baptist Gospel reports [...] So John tells in his Gospel what Christ had done before the Baptist was thrown into prison; but the other three evangelists report the events following the incarceration of the Baptist. "

The Muratori canon , which reports the origin of the Gospel of John, is also likely to date from the end of the 2nd century :

“The fourth of the Gospels, of John, [one] of the disciples. When his fellow disciples and bishops asked him [to write down], he said: "Fast with me from three days from today, and we will tell each other what will be revealed to each one." That same night it was revealed to Andrew, [one] of the apostles, that John should write everything in his name and everyone should check it out. And therefore, even if different details are taught in the individual books of the Gospels, it has no effect on the faith of the believers, since everything is explained by the one divine Spirit to all [in all Gospels]: the birth, the suffering, the resurrection, the intercourse with his disciples and about his double arrival, firstly, in humility, despises what has happened, secondly, in glorious royal power, what is yet to happen. So what wonder when Johannes, so constant, also brings up the individual in his letters, where he says of himself: What we saw with our eyes and heard with our ears and felt our hands, we wrote to you . For with this he confesses not only as an eye and ear witness, but also as a writer of all the miracles of the Lord in turn. "

The Christian tradition therefore fills the empty space of the favorite disciple in John's Gospel with the person of the apostle John.

The "Johannine Question"

The silence of the Gospel of John about the identity of the favorite disciple is the actual reason for the "Johannine question". Historical-critical research criticizes the traditional view and makes the following arguments:

- The early Christian testimonies seem (too) to try hard not only to highlight and legitimize the apostle John as the author, but also to compensate for the differences between John and the Synoptics retrospectively. The apologetic character of this company seems clear. The testimony of the Muratori Canon is too legendary to be considered historically reliable.

- According to an alternative tradition from the Gospel of Mark ( Mk 10: 35–41 EU ), the apostle John, like his brother James , could have suffered martyrdom at an early age. Since Mark already seems to be looking back on this event, the death of John should be set before the year 70 at the latest as the date of the writing of the Gospel of Mark. According to this view, the apostle could not have died of old age in Ephesus.

- The silence of some other authors speaks against the tradition of Irenaeus, from whom one would have to assume that they would confirm it. These include above all Ignatius of Antioch and Justin the Martyr .

- It is difficult to imagine that the naming of an apostle and intimate disciple of Jesus would be dispensed with if he were actually the main author of the gospel.

- On the other hand, it is believed that the author is not named because he had no apostolic authority and was therefore not generally recognized. This would rule out the identification with the apostle John.

- Ultimately, the favorite disciple is completely denied a real existence and a literary, fictional figure is seen in him.

However, none of these arguments are compelling. A martyrdom of the apostle John is inferred from the Gospel of Mark, but is not specifically proven and therefore uncertain. The silence of other texts about the apostle John can have various reasons. In this respect one cannot claim that the early Church's testimony, especially with Irenaeus and Eusebius, has been refuted. However, your information cannot be verified by independent sources, so that ultimately it must remain open whether the Evangelist John is actually identical with the Apostle John. However, the existence of a pseudepigraphy cannot be ruled out either, which ascribes the author a role in the disciples' circle in order to give the text of John's Gospel authority in this way.

The literary scholar CS Lewis said that the narration of the Gospel of John shows that it was written by an eyewitness.

The Evangelist and the Epistles of John

The Evangelist John is also traditionally considered to be the author of the three letters of John ( 1 Joh EU ; 2 Joh EU and 3 Joh EU ).

For the first letter of John this is largely undisputed. Internal reasons are also given for this, especially the similarities in the language. However, this picture does not apply equally to the 2nd and 3rd letters of John. They both come from a single source, but this is hardly identical to the hand of the evangelist. Above all, it is the self-designation as “presbyter” (“elder”) that does not suggest the authorship of the “favorite disciple” - as in the Gospel. In some cases, research also flatly denies that the evangelist and above all the apostle John were authorship of all three letters. All three letters, however, were probably written at least in the same "Johannine school", probably in Ephesus.

The Evangelist and Revelation

The evangelist is also traditionally considered to be the author of the Revelation of John . In addition to Rev 1,1 EU , this view is mainly based on Rev 1,9–11 EU :

“I, your brother John, who is besieged like you, who shares with you in the kingdom and stands steadfast with you in Jesus, I was on the island of Patmos for the word of God and the testimony for Jesus. On the Lord's day, I was seized by the Spirit and heard a voice behind me, loud as a trumpet. She said: Write what you see in a book and send it to the seven churches: to Ephesus, to Smyrna, to Pergamon, to Thyatira, to Sardis, to Philadelphia and to Laodicea. "

Apart from this name correspondence, there is hardly any evidence of an identity between the author of the Revelation and the Apostle John or the Evangelist. In the Christian tradition, the apostle John is accepted as the author of the Revelation as early as the 2nd century and equated with the evangelist, above all by Eusebius, who in turn refers to Irenaeus (Adv Haer V, 30.3): “ It becomes relates that in this persecution the apostle and evangelist John, who was still alive, was condemned to stay on the island of Patmos because of his testimony to the divine word ”.

This view was criticized by Dionysius of Alexandria († 264) as early as the 3rd century :

“Completely different and alien to these writings [the gospel and the letters of John] is the apocalypse. There is no connection or relationship. Yes, it has hardly a syllable in common with it, so to speak. Neither does the letter - not to speak of the Gospel - contain any mention or thought of the apocalypse, nor does the apocalypse of the letter [...] "

In the Revelation the name of its author is given four times as "John" ( Rev 1,1 EU ; 1,4.9 EU ; 22,8 EU ), but this has nothing in common with the evangelist except what is assumed by church tradition Names. In addition, the author also seems to differ from the apostles ( Rev. 18.20 EU ; 21.14 EU ). Today the evangelist's authorship for revelation is largely excluded in scientific research. There are significant differences in language, eschatology , christology and ecclesiology . Exegesis thus distinguishes John of Revelation from both the evangelist and the apostle John. Nonetheless, Jens W. Taeger sees connecting lines between the Apocalypse and Deutero-Johannine thinking, namely the letters of John and the editorial level of the Gospel of John that he assumed.

chronology

The Gospel of John provides the most decisive clues for the question of the chronological dates of the evangelist. The Papyrus 52 , which was found in Egypt, is the oldest known text testimony of John's Gospel. It is dated to about the time between 100 and 150 AD. At this point in time, the gospel must have already existed and been so widespread that it could have reached Egypt. For such a dissemination some time after the drafting has to be planned. If the main author was a disciple of Jesus and the year of Jesus' death fell around the year 30 AD, the evangelist will have lived until around the beginning of the 2nd century at the latest.

For internal reasons, the majority of researchers refuse to write the Gospel before the year AD 70. Accordingly, the author looks back on a historical situation of extensive alienation between the Johannine community and Judaism, which is only conceivable after the destruction of the temple in 70. Therefore, the time of writing the Gospel is set at the end of the 1st or the beginning of the 2nd century AD.

This conclusion is confirmed by the early church evidence of the identity of the apostle John with the evangelist. Irenaeus says:

“And all the presbyters who came together in Asia with John the Lord's disciple testify that John narrated this. Because he stayed with them until the time of Trajan. "

Citing Irenaeus, Eusebius also reports on the death of the apostle in Ephesus under Emperor Trajan (Eusebius, Hist Eccl III, 23.3). The term of office of Trajan lasted from 98 to 117 AD, so that the evangelist could not have died until 98 AD at the earliest. This information corresponds to the chronological framework that the Gospel also sets. In the New Testament, however, there is no evidence that the apostle John stayed in Asia Minor. Above all, the Acts of the Apostles and Paul's letter to the Ephesians know nothing of this. However, the New Testament only reports directly on a time that was before the presumed time of writing the gospel.

place

The evangelist undoubtedly has an in-depth knowledge of the geographical, religious and sociological conditions in Palestine at the time of Jesus. This is also evident in his presentation of the chronology of the Passion of Jesus, which is still the least contradictory. Due to his strongly Semitic influenced Greek language, one can assume that he grew up in Palestine, i.e. that he was a Jew born in the Jewish motherland. The statements of the Gospel about the “favorite disciple” are thus supported by literary observations.

However, there are no clear indications in the Gospel or in First John for a later stay of the evangelist in Ephesus in Asia Minor . All of this speaks rather against an origin in a Greco-Gentile Christian context in Ephesus, where the church tradition going back to Irenaeus settles it. By Klaus Wengst addition, it is argued, the Evangelist So that the historical background of John's debates with are likely to have played mainly in Syria-Palestine area "the Jews", and it therefore can accept that the Gospel was created here, is stayed in Palestine in his later years. However, this conclusion is not mandatory, because one does not have to be on site for the literary formation of a conflict; Nor is it excluded that a Palestinian Jew will later settle in Asia Minor.

Therefore, for the question of the further residence and place of death of the evangelist compared to the knowledge gained from the gospel, the references of the early Christian authors who identify the apostle John with the evangelist remain in place. Here again Irenaeus provides the decisive statement for Ephesus as the last place of residence and then also the place of death:

"The church in Ephesus founded by Paul, in which John stayed continuously until the time of Trajan, is a faithful witness to the apostolic tradition."

A decision on the local assignment is not possible in view of these different perspectives.

The evangelist in the Christian tradition

Through the identification of the evangelist with the apostle John, the Christian tradition had a considerable influence on the image of the evangelist since the first testimonies of the church fathers Irenaeus and Eusebius . This influence was reflected not only in many written documents since the time of the Church Fathers, but also in many ways in the fine arts.

The apostle John and the favorite disciple in the New Testament

According to the synoptic testimony ( Mk 1,19-20 EU ) the apostle John was the younger brother of the apostle James the Elder . Both were called by Jesus together while they were doing their job as fishermen - together with their father Zebedee. That is why they are also referred to as "sons of Zebedee" in tradition. With the Synoptics, you and Peter have a particularly close relationship with Jesus ( Mk 9.2 EU ; 14.33 EU ).

Nothing is told in the Gospel of John about the calling of the Zebedee sons. However, they appear in the final chapter alongside two other nameless disciples ( Joh 21,2 EU ). Later, a disciple from this group is referred to as the “favorite disciple” (21.7 EU ) without establishing a relationship with the Zebedee sons. Identification remains possible, but is not mandatory.

Compared to the Zebedee sons among the Synoptics, the favorite disciple in John's Gospel is even more intimate with Jesus:

- During the common meal of the disciples before the Passion, he lies on the “breast” of Jesus and is referred to for the first time in this scene as “the disciple whom Jesus loved” ( Jn 13:23 EU ).

- He stands under the cross with Mary, the mother of Jesus, and receives a special commission from Jesus towards her (19.26 EU ).

- He and Peter are one of the first to come to the tomb of Jesus and thus become a witness of the resurrection (20.2 EU ).

- He identifies the risen Jesus in front of the disciples (21.7 EU ).

- At the end of the Gospel of John he is not only highlighted as its author (21.24 EU ), but Jesus also honors him with a special prophecy (21.20-23 EU ).

These characterizations in John's Gospel, together with the synoptic tradition, led to the high esteem that the evangelist and apostle gained in the tradition of tradition. Alongside Paul, he is probably the most formative personality among the New Testament authors.

Later traditions about the evangelist

Other testimonies about the life of the evangelist have come down to us from ecclesiastical writers from the first centuries. After he left Palestine, he is said to have preached the gospel in Asia Minor and settled in Ephesus, where he also died.

The tradition goes back to the identification with the author of the Revelation that the apostle and evangelist was banished under Emperor Domitian (81-96 AD) to the island of Patmos , which is located southwest of Ephesus in the Aegean Sea . Here a "St. John's Grotto" is still venerated as one of the most important shrines of the Greek Orthodox Church . The grotto is located between Skala and Chora and can be found inside the church of Ag. Anna , which was built in 1090 and belongs to the Orthodox Revelation Monastery. Legend has it that the apostle wrote the revelation in this rock cave.

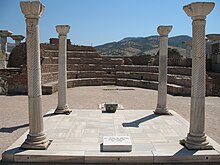

After Domitian's death , John is said to have returned from exile in Ephesus and wrote down his gospel there. According to this tradition, he died in Ephesus under Emperor Trajan , in the third year of his reign. Accordingly, the year of death would have to be dated to 100 or 101 AD. According to Eusebius, who referred to a letter from Bishop Polykrates to Pope Viktor I , John was also buried in Ephesus (Hist Eccl III 31,3). Helena , mother of Emperor Constantine the Great , had a church built over the site, which is considered the evangelist's grave . Emperor Justinian replaced it with a monumental building. The remains of the Johanneskirche can still be visited today.

Significance from fatherhood to today

The literary and theological achievement of the evangelist as the author of the fourth gospel is undisputed, which takes a very independent and theologically strongly reflected way of presenting Christian beliefs. Jerome gives the following interpretation of the eagle as a symbol of the fourth evangelist:

"John received the eagle because in the prologue about the Word that was with God in the beginning, it rises higher than the others and soars into the highest regions, like an eagle rises to the sun."

In addition, the evangelist and apostle John is considered an ecclesiastical authority. According to tradition, his students included the bishops Polycarp of Smyrna , Ignatius of Antioch , Papias of Hierapolis and Bishop Bucolus of Smyrna . The Church Father Augustine (AD 354–430) wrote about John :

“In the four gospels, or rather in the four books of one gospel, the holy apostle and evangelist John, who according to his spiritual knowledge is compared to the eagle, raised his preaching higher and far more exalted than the other three and thereby wanted to elevate us too. For the other three evangelists walked the earth with the God-man, as it were, and said less about his Godhead; But the latter, as if he spurned walking on earth, has, as he thundered at the beginning of his gospel, not only risen above the earth, but also above the whole host of angels, etc., and has come to him, by whom everything is made by saying: 'In the beginning was the word'. That flowed from his mouth what he drank; for it is not without reason that it is said of him in this Gospel that he lay on the Lord's breast at the Lord's Supper. He drank from this breast in secret; but what he drank in secret, he evidently emitted. "

This appreciation was also z. B. from Pope Benedict XVI. shared, who commented specifically on the "Johannine question" and wants to adhere to the fact that the favorite disciple and apostle John was an eyewitness to a historical event about Jesus and brought this memory into church tradition.

liturgy

The feast of St. John the apostle and evangelist is celebrated in the Catholic and Protestant churches on December 27th. In the Catholic Church, on this feast, Johanneswein can be blessed according to an old custom . The Orthodox churches celebrate the saint on May 8th.

coat of arms

The city of Sundern (Sauerland) has the evangelist Johannes in its coat of arms . Blazon: In silver a growing golden nimbly John in blue robe and with golden hair, holding a golden chalice in his right hand, above which a blue snake hovers.

literature

- Charles K. Barrett: The Gospel According to John . Göttingen 1990, ISBN 3-525-51623-1

- Klaus Berger : In the beginning there was Johannes. Dating and theology of the fourth gospel. Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-7918-1434-6

- Ingo Broer : Introduction to the New Testament. Study edition Volumes I + II . Würzburg 2006, pp. 189-215, ISBN 3-429-02846-9

- Christian Dietzfelbinger : The Gospel according to Johannes . Zurich 2004, ISBN 3-290-14743-6

- Erhard Gorys : Lexicon of the saints . dtv, 2nd edition, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-423-32507-0

- Manfred Görg: Art. Revelation of John , in: New Bible Lexicon. Edited by M. Görg and B. Lang, Vol. III. Zurich 2001, Sp. 21-26, ISBN 3-545-23076-7

- Martin Hengel : The Johannine question. An attempted solution, with a contribution to the Apocalypse by Jörg Frey . Tübingen 1993 = WUNT 67, ISBN 3-16-146292-0

- Hans-Joachim Klauck: Art. Johannesbriefe , in: New Bible Lexicon. Edited by M. Görg and B. Lang. Vol II Zurich 1995, Sp. 350–353, ISBN 3-545-23075-9

- Joachim Kügler : The disciple whom Jesus loved. Literary, theological and historical research on a key figure in Johannine theology and history. With an excursus about the bread speech in Joh 6 , Stuttgart 1988 = SBB 16, ISBN 3-460-00161-5

- Lorenz Oberlinner: Art. Johannes (Apostle) , in: New Bible Lexicon. Edited by M. Görg and B. Lang. Vol II Zurich 1995, Sp. 350–353, ISBN 3-545-23075-9

- Joseph Ratzinger : Jesus von Nazareth , Freiburg 2007, ISBN 3-451-29861-9

- Rudolf Schnackenburg : The Gospel of John , part 1–3, Freiburg, Basel, Vienna 1965–1992

- Werner Schulz: John the Apostle. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 3, Bautz, Herzberg 1992, ISBN 3-88309-035-2 , Sp. 265-266.

- Benedikt Schwank : Gospel according to Johannes. Practical comment . EOS, Sankt Ottilien 3rd edition 2007. ISBN 978-3-8306-7270-8

- Hartwig Thyen: The Gospel of John . Tübingen 2006 = HNT 6, ISBN 3-16-148485-1

- Klaus Wengst : Afflicted community and glorified Christ. An attempt on the Gospel of John , Munich 1990, ISBN 3-459-01861-5

See also

Web links

- Literature by and about Johannes in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Johannes in the German Digital Library

- John in the ecumenical dictionary of saints

- John in the Catholic Encyclopedia (English)

- The 21 chapters of the Gospel of John to read and to listen to on the computer . (Text bible)

Individual evidence

- ↑ MJM Mehlig (1758), Historical Church and Heretic Lexicon, Volume 2, p. 364

- ↑ See M. Hengel, Die Johanneische Question

- ↑ Irenäus, Adv Haer III 1,1, also cited in Eusebius, Hist Eccl V 8,4

- ↑ Eusebius of Caesarea: Church history III 24, 6 f. 11 f., Trans. by Philipp Haeuser (= BKV II.1), Munich 1932, pp. 130-132

- ↑ Kanon Muratori, lines 9-16, after Hans Lietzmann (Ed.): The Muratoric Fragment and the Monarchian Prologues to the Gospels , Small Texts for Lectures and Exercises 1, Bonn 1902 (2nd edition Berlin 1933)

- ^ R. Schnackenburg, Johannesevangelium , Vol. 1, p. 69

- ↑ L. Oberlinner, Johannes (Apostel) , Col. 351

- ^ CK Barrett, The Gospel According to John , p. 139

- ↑ M. Hengel, The Johannine Question , pp. 18-19

- ↑ M. Hengel, The Johannine Question , pp. 19-20.

- ↑ So z. BH Thyen: The Gospel of John , p. 794: “The beloved disciple [is] the fictional evangelist in the gospel, created, narrated and narrated by the real evangelist ”; see. also J. Kügler, The Disciple whom Jesus loved .

- ↑ Ingo Broer: Introduction to the New Testament , Würzburg 2006, p. 193 ff.

- ↑ Clive Staples Lewis: Fern Seeds and Elephants, 1959 , orthodox-web.tripod.com , accessed January 13, 2020.

- ^ I. Broer, Introduction to the New Testament , pp. 243–247

- ↑ H.-J. Klauck, Art. Johannesbriefe , Col. 355

- ↑ NRSV Rev. 1.9 to 11 EU

- ↑ Eusebius, Hist Eccl III 18.1

- ↑ Dionysius of Alexandria quoted from Eusebius, Hist Eccl VII 25. Thomas Söding , Robert Vorholt : “In the beginning was the word” · The Gospel of John ( German , PDF; 594 kB) Ruhr University Bochum, Catholic Theological Faculty, New Testament Chair . See also: Eusebius von Caesarea , Dionysius: Kirchengeschichte (Historia Ecclesiastica) ( German ) University of Freiburg, CH, Greek patristic and oriental languages. January 1, 2008. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ C K. Barrett, The Gospel According to John , p. 117

- ↑ Thomas Söding: The Book with Seven Seals - The Revelation of John, Lecture WS 2007/08, p. 7 (PDF; 160 kB), accessed on December 17, 2011

- ↑ M. Görg, Art. Revelation of Johannes , Col. 22

- ↑ Jens W. Taeger: Johannes apocalypse and Johannine circle. Attempt to determine the place of origin in the history of tradition using the paradigm of the water of life topic . BZNW 51, Berlin, New York 1989

- ^ John Rylands University Library Manchester : 1st half of the 2nd century

- ↑ Ingo Broer: Introduction to the New Testament , Würzburg 2006, p. 206 f.

- ↑ K. Wengst, Bedrehte Gemeinde , pp. 75–122

- ↑ Irenäus, Adv Haer II, 22.5

- ↑ I. Broer, Introduction to the New Testament , pp. 208–215

- ^ K. Wengst, Bedrehte Gemeinde , pp. 158–179

- ↑ Irenäus Adv haer III, 3.4

- ↑ See above the testimonies of Irenaeus and Eusebius.

- ^ Mike Gerrard, Greece , National Geographic Treveller 2007, p. 268

- ↑ The legend of the Johannesgrotto inspired Friedrich Hölderlin to write the poem Patmos : "And since I heard / The one nearby / Be Patmos / I wanted very much / to stop there and there / to approach the dark grotto". Hölderlin: Patmos , in: Works in two volumes. First volume. Hanser, Munich 1978, p. 379 ff.

- ↑ Hieronymus, preface to the Matthew commentary

- ^ Augustine, Tract. 36. in Joh. No. 1

- ^ Joseph Ratzinger, Jesus von Nazareth , Part One, 2nd ed. 2007, pp. 260–280. Ratzinger, p. 268 f., Ascribes an essential function to the presbyter Johannes, who is to be distinguished from the apostle Johannes, in the final form of the text of the Gospel: “[...] with whom he [Presbyter Johannes] always himself as trustee of the tradition received from the Zebedaiden [Apostle John]. “ In the memory both figures finally merged more and more.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | John |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | evangelist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1st century |

| DATE OF DEATH | 1st century or 2nd century |