French zone of occupation

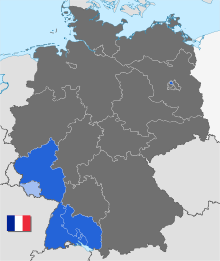

A part of Germany that was occupied by France as one of the victorious powers of the anti-Hitler coalition after the end of World War II is referred to as the French occupation zone . The French zone of occupation was one of four zones of occupation in Germany after the war. The northern zone was formed from the southern part of the Rhine Province , the western part of Nassau , the left-hand part of Rheinhessen and the Rhine Palatinate and the southern zone from Württemberg-Hohenzollern , southern Baden and the Bavarian district of Lindau . Until 1946 the Saarland was also part of the French zone.

prehistory

During the Yalta Conference in February 1945, the three main powers of the anti-Hitler coalition decided to identify an area of the British and American occupation zones that could be occupied by French forces. France should be consulted about its size, and the decision should then be made by the Americans and the British. The Provisional Government of France has been invited to become a member of the Allied Control Council for Germany .

Due to the repeated demands of Charles de Gaulle and the mediation of Winston Churchill , France had achieved the status of a victorious power against the resistance of Stalin and Roosevelt , De Gaulle, for his part, saw in American European policy an imperialist endeavor to order the continent according to their interests. He insisted on France's participation in a post-war European order. After French troops occupied extensive areas in southern Germany in April 1945, France formally received its own occupation zone in southern Germany in June 1945, six weeks after the surrender of the Wehrmacht , the regulation of which had been prepared by the EAC for a decision at the Potsdam Conference .

After the military catastrophe of 1940, General de Gaulle - since October 1944 president of a French government recognized under international law consisting of communists, socialists and conservatives - followed the vision of restoring France's former importance as a major European power. Security from an aggressive Germany was much more important for France than it was for the "Big Three", Great Britain, the United States and the Soviet Union. De Gaulle's understanding of German history made him differentiate between the “great German people” of the various tribes and the “trouble spot of the German nation-state, as it was shown in 1866, 1870 and 1914”, dominated by one country (i.e. Prussia ).

De Gaulle's policy on Germany after the liberation of France in 1944 was therefore the entry into the war on the side of the Allies, "without unconditional submission to them", the dissolution of the Reich and reorganization in individual states, the denazification of the German population and the establishment of a democracy under time unlimited allied sovereignty. De Gaulle did not address an annexation of areas on the left bank of the Rhine in 1944, but called for the Rhineland and the industrial area on the Ruhr to be internationalized under permanent Belgian, British, French and Dutch control.

Conquest and occupation in 1945

The areas on the left bank of the Rhine in Germany were conquered from France by the 1st, 3rd and 7th US Army by March 1945. Coming from southern France, the head of the French 1st Army ("armée de Rhin et Danube"), attached to the 6th US Army Group , reached the German-French border in the Karlsruhe area at the end of March. Already on 18./19. On March 25th, soldiers of the 3rd Algerian Infantry Division under Lieutenant General Goislard de Montsabert were the first German town to be captured by the French, in the southern Palatinate town of Scheibenhardt on the Lauter . In association with American troops of the 7th US Army , the Palatinate was taken up to Speyer. On March 29, de Gaulle had instructed the commanding general de Lattre de Tassigny "to cross the Rhine, even if the Americans are against it." From this request de Gaulle followed arbitrary decisions, the non-observance of the operational plans of the commanding 6th US Army Group and a race with the US armed forces to gain ground. No one adhered to the dividing line between Karlsruhe and Ulm, which the Americans had assigned a northern part of Württemberg and the French a southern part of Württemberg to occupy. The French reached Stuttgart on April 21 and only handed the city over to the Americans on July 8, after repeated requests, after General Eisenhower had threatened to suspend supplies to the French troops.

By the end of April, the French had advanced across the Black Forest and north of Lake Constance to Vorarlberg and Tyrol to create a connection to their Austrian zone of occupation. At the beginning of May 1945 the remnants of the German 19th Army surrendered in Innsbruck and the war in the southwest was over.

After crossing the Rhine, the French troops regularly looted in the first few days in the areas they occupied before the German surrender , in numerous cases killings and also mass rapes . The French officers partly let their troops do theirs, only intervened after a few days, then often drastically by executing soldiers without trial. Numerous local reports attest to this. In Reutlingen, the captain of the security service of the French army, Max Rouché - a professor of German studies in Bordeaux - had four German civilians executed as hostages on April 24, 1945 as reprisal of the suspected assassination death of a French soldier who probably died in a traffic accident.

In the conquered and occupied territories, military commanderships formed local regimes with far-reaching powers, as the French government had not yet given any binding responsibilities. In the resulting power vacuum, the military acted on their own. With their appearance and regime they were reminiscent of the generals of the French Revolution, who from 1792 had conquered the left-wing Rhineland in the First Coalition War and plundered it to supply their troops.

The behavior of the French towards the German population during the initial occupation was determined by fear of acts of sabotage, retribution for four years of German occupation in the mother country and doubts about a real end to National Socialism . The first internal poor instructions and the public announcements prove the lawlessness of the population and expected an unconditional compliance with orders of the military, e.g. B. the execution of ten Germans was threatened for a wounded or killed French soldier. The district administrator of Mainz complained: that the individual troops commandeer at will in the individual villages, [...] young calves and piglets are slaughtered at random. The arbitrary treatment of the population and unauthorized requisitioning was punished by higher officers with disciplinary punishments and called upon to impart "the strength, dignity and discipline of France" to the Germans.

area

The French occupation zone in Germany was formed from parts of the West and Southwest German zones conquered by American and French troops, into which Germany had been divided by the Four Powers after the unconditional surrender of the Wehrmacht . From July 1945 the south-west German areas of the British and American occupation zones were handed over to the French in accordance with the Berlin Declaration and Zone Protocol of June 5, 1945.

The zone boundaries were often set arbitrarily without reference to historically evolved courses. The former Prussian Rhine Province was divided into a British northern part and a French southern part. Further south, the Rhine formed a new border between the French-occupied city of Mainz and its then American-occupied districts on the right bank of the Rhine . Another border between the American and French zones was the border along the Karlsruhe-Ulm motorway, which was formed for purely logistical reasons. The resulting French zone consisted of two triangles of approximately the same size, which were only connected south of Karlsruhe by an American-controlled railway bridge over the Rhine and 15 kilometers of road.

The zone comprised 8.5 percent of the German Empire in the 1937 borders, which was roughly the size of the Netherlands. With exceptions along the Rhine and a few cities in Württemberg, the zone was a largely agricultural landscape that had suffered less from the bombing than the rest of the empire. In places with less than 10,000 inhabitants, almost 90 percent of the residential buildings were therefore still intact. The cities on the major railway lines, transport hubs, train stations and industrial sites, on the other hand, were largely in ruins. Koblenz was more than 80 percent destroyed. In May 1945 there was 1.8 million cubic meters of rubble in the city of Mainz, which the population had to remove with shovels, pickaxes and wheelbarrows. In the Saar area, 60 percent of the heavy industry was destroyed. Only 6 percent of the BASF factory buildings in Ludwigshafen were preserved. Major bridges lay blown up in the rivers. Impassable tunnels, destroyed rail tracks and streets narrowed by bomb craters and building rubble to paths had collapsed the transport infrastructure and were one of the reasons for the catastrophic supply situation for the population until well into 1948.

Initially, the French occupation was divided into the provinces of Baden (main town Freiburg), Württemberg-Hohenzollern (Tübingen), Palatinate-Rheinhessen (Neustadt), Rhineland and Hesse-Nassau (Bad Ems) and Saar (Saarbrücken). In 1946, under the supervision of the French military government, the states of Baden , Württemberg-Hohenzollern and Rhineland-Palatinate, as well as Saarland , were spun off from the French occupation zone in February 1946 with the tacit tolerance of the Allies and became the Saar Protectorate ( Protectorat de la Sarre, Gouvernement Militaire de la Sarre (GMSA)) was placed under a special regime, with the aim of integrating it into the territory of the IV French Republic.In July 1946, parts of the districts of Trier , Saarburg and St. Wendel were spun off from the French occupation zone and attached to the Saarland . In some regions close to the border with Luxembourg, Belgium and the British zone of occupation, e.g. For example, there were efforts by the population to leave the French zone and integrate into a region that was regarded as better economically.

In 1946/1947 efforts were made in the Palatinate to separate this province, "[...] to turn away forever from this bellicose Prussia", as it was formulated at an autonomist rally. The separatist plans ended with little interest among the population and strong rejection of the military government.

There was also a French sector in Berlin in the West Berlin districts of Reinickendorf and Wedding, alongside the sectors of the USA , Great Britain and the Soviet Union .

On May 23, 1949, the states of Rhineland-Palatinate, Baden and Württemberg-Hohenzollern became part of the Federal Republic of Germany . As early as 1952, the states of Baden and Württemberg-Hohenzollern merged with the state of Württemberg-Baden formed by the American military government to form the state of Baden-Württemberg . The Saarland did not join the Federal Republic until 1957, after the Saar Statute was rejected in a referendum on October 23, 1955 .

The Bavarian district of Lindau also belonged to the French occupation zone . This served as a connecting corridor to the French-occupied zone in western Austria . The district was reintegrated into Bavaria on September 1, 1955.

Military government and civil administration

The first military governor and commander in chief of the French occupation forces in Germany was Jean de Lattre de Tassigny , commander in chief of the 1st French Army (later: Rhin et Danube ) . De Lattre was recalled in July 1945. The trigger or reasons for this were probably his extravagant command style ("the uncrowned King of Lindau") and frequent vetoes in the Allied Control Council . His successor was Marie-Pierre Kœnig , who held the post of "Commandant en chef français en Allemagne" in the French occupation zone until September 21, 1949. The seat of the central military government ("Gouvernement militaire de la zone française d'occupation") had been Baden-Baden since the end of July 1945 . In September 1945 the five regional military governments ("Délégations Supérieures") were established in Württemberg-Hohenzollern , South Baden , Hesse-Palatinate , Rhineland-Hesse-Nassau and the Saarland .

The work of the occupation administration suffered initially from the disputes over competencies between the professional soldiers of the regular army and the civil servants from the Resistance who were often experienced in administrative matters. The dispute over the direction between General Kœnig and his head of administration Émile Laffon has become a well-known example of this. Governors were used for civil administration , such as B. Claude Hettier de Boislambert for the former Prussian administrative districts of Trier and Koblenz, from which the Upper Presidium of Rhineland-Hesse-Nassau was formed on January 3, 1946. In the French zone there was a bureaucratically tight regulation of the population, often afflicted with a winning mentality; public life was soon restored in the British and American zones.

From July 31, 1945, the lower administrative levels of the administrative districts, rural and urban districts and the municipalities were used for zone administration. The presidents of the administrative districts of the former German Reich were responsible for executing the occupation instructions. Its main task, in addition to managing a shortage of almost all essential goods and starting a reconstruction, was the execution of instructions and special requests from the occupying power, which in 1946 worsened the supply situation with almost a million people - military and relatives.

A kind of government was formed by the general directorates for economy, administration, finance, disarmament control and justice, based in Baden-Baden. With the re-establishment of the states of Rhineland-Palatinate , Baden and Württemberg-Hohenzollern in 1946, governors became the highest representatives of the occupying power. The governor for Rhineland-Palatinate was Claude Hettier de Boislambert , the governor for Baden was Pierre Pène and the governor for Württemberg-Hohenzollern was Guillaume Widmer . Until the establishment of the Occupation Statute in 1949, they were largely subordinate to the minister-presidents of the federal states on the German side.

With the formation of the Allied High Commission , based on the Petersberg near Bonn in September 1949, the office of military governor was replaced by the office of the High Commissioner . André François-Poncet was the High Commissioner for the French zone of occupation from August 10, 1949 to May 5, 1955 . In the course of this, the seat of the French occupation administration was moved from Baden-Baden to the Petersberg.

Requisitions, reparations and occupation costs

The resolutions of the Potsdam Conference in August 1945 between Great Britain , the United States of America and the Soviet Union also contained the agreements on German reparations to make good the damage Germany caused to the economy and the property of its opponents. In contrast to the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, Germany was not obliged to make long-term payments and withdrawals from ongoing industrial production; instead, all of its foreign assets were confiscated and administered. In addition, parts of the industry were planned to be dismantled. It was left to the powers that be how they would enforce their demands. France, which did not feel bound by the Potsdam decisions (especially the treatment of Germany as an economic entity), primarily pursued the compensation of its losses by the German occupation 1940-1944, which were estimated at 160 billion Reichsmarks . The index of France's industrial production had fallen from 100 (1929) to 29 (1944), agricultural yields had fallen by an average of up to 40% in 1945 and the official food rations for an adult in Paris in 1944 were only 1200 kcal per day. France therefore had an existential interest in using its zone of occupation for supplies.

Steel production and coal mining in the Saar area were used to strengthen its domestic industry and energy needs . In order to supply the troops, their families and the population in the mother country, the higher quality agricultural products, cattle, textiles etc. were requisitioned or diverted from the supply of the German population. A deforestation program went beyond the normal cutting approaches with almost 350% and left huge clear-cutting areas in the densely wooded south-west of Germany.

Hermann Ebeling , who worked as a representative of the CRALOG in the French occupation zone, reported under his pseudonym Henry Wilde in an article for the newspaper Das Andere Deutschland ( La Otra Alemania ) in Argentina on black immigration , which mainly included the southern part of the Occupation zone, the area around Freiburg and Baden-Baden suffered. “Occupation troops with their families are housed everywhere. Baden-Baden, the administrative capital of the entire zone with a peacetime population of less than 30,000, is home to between 30,000 and 40,000 French. The members of the French garrison are of course much better off here than in France, and often the French soldier or officer, whose sense of family is proverbial, not only allows wives and children to follow, but also parents and parents-in-law with widely ramified followers. While this is not always entirely legal, black immigration to the zone is not very difficult. Everyone knows about it. And nobody does anything about it. In January of this year, the French population in the total zone was around 600,000. The flow of immigrants is still steady. Under such circumstances there is a terrible housing shortage and [..] nutritional difficulties in the well-preserved cities. "

This black immigration went hand in hand with the requisition of private furniture, linen, clothing and complete kitchen facilities , which the population perceived as a further harassment . Even after three years of occupation, the Prime Minister Peter Altmeier of the State of Rhineland-Palatinate complained to Governor Hettier de Boislambert about the constant requisitions, which u. a. between October 1947 and March 1948 amounted to more than 300,000 sheets, 100,000 cutlery, 18,000 ceiling lamps, etc. A particular annoyance was when the French took away the requisitioned items from private households when they were transferred or returned to the mother country. The fact that many German households were better equipped than the average French household even led to a debate in the National Assembly about justified taking along. In contrast to the USA and Great Britain ( £ 80 million in 1946 alone ), France did not have to invest anything in its zone until the end of 1947. On the other hand, the costs of the occupation exceeded those of the American and British zones and amounted to e.g. B. in the state of Württemberg-Hohenzollern still half of his household in 1951. In 1949, 104 Deutsche Marks per inhabitant were paid for the French, 77 DM for the British and 92 DM for the Americans.

The French occupation forces also confiscated assets (16% of bank balances, gold, securities and property belonged to France) and production facilities (only 40% of the allocated facilities were dismantled). It was one of France's goals to weaken Germany economically and militarily so that it could no longer pose a threat to France in the future.

Population and occupation

Quarterly "Political Situation Reports" by the German government presidents and monthly "Bulletins" by the French high commanders reported from autumn 1945 a. a. the current political situation, the economic and supply situation, denazification, the relationship between the authorities and the occupation, and more. The minutes of the “Mixed Commission” - a first German self-governing body set up by the French government in September 1946 - recorded special incidents, the distribution of tasks, and also complaints and reprimands.

General political situation

Dealing with the catastrophic food and housing supply, especially in the cities, was an overriding problem for the zone population until 1949. “The confrontation with poverty and misery appeared unbearable to the Germans. In their deep apathy, they thought more of the next day's food than of the future of Germany ”(French bulletin for the reporting period January 1946). In the same year, a German report complained that a loss of reality in the population did not see the emergency as the effects of its own past, but rather blamed the authorities and the occupation. Three years after the end of the “Third Reich”, the population was still preoccupied with their everyday problems and was hardly interested in political participation. In the referendum on the constitution of Rhineland-Palatinate z. B. [...] one should not be mistaken about the fact that most of the voters neither knew the content of the constitution nor regretted the belated publication of the draft. "The German of 1948 is not yet a democrat."

Living

The proportion of living space destroyed was statistically slightly lower in the French zone than in the British and American zones. In the large and medium-sized cities, 45 percent were completely or partially destroyed. More than 70 percent of the centers of Koblenz, Ludwigshafen, Mainz and other major traffic cities were bombed. Counted z. B. Koblenz in 1939 25,362 apartments, in April 1945 it was 9,880. In rural areas with less than 10,000 inhabitants, 90 percent of the living space was still intact.

Housing management in the zone was responsible for almost six million Germans, around 175,000 "displaced persons" (former forced and foreign workers, released concentration camps and prisoners of war, etc.). In addition, from 1946 onwards for one million soldiers and civilians of the occupation, for whose families the more comfortable, better furnished apartments had to be confiscated; on June 30, 1948, the Rhineland-Palatinate Prime Minister Altmeier reported to the French governor de Boislambert of an increase in the confiscated living space of 67,083 m². The total area of the confiscated apartments was 1,624,354 m² with a total of 24,294,695 m² of living space.

In order to regulate the housing needs of the zone residents, all persons who had only taken up residence in the French zone after 1939 (refugees and evacuees) were asked to leave the zone. In the Reg.-Bez. Koblenz z. B. In November 1945 there were 71,719 people. In addition, the German authorities resisted the admission of expellees and ethnic Germans from the East and justified their resistance with a lack of housing and supply problems, but also with the danger of denominational and different foreign infiltration of the local population. Due to the admission of refugee contingents decided in the Allied Control Council, z. For example, the northern zone (Rhineland-Palatinate) reluctantly only allowed around 90,000 people to move in until October 1948.

nutrition

Even before the Second World War, the countries of the French zone were dependent on imports of basic foodstuffs despite their largely agrarian structure. War-related failures in agricultural production, the destruction of transport and traffic facilities, had dramatic effects on the supply of the population. The rationed allocation of everyday goods, introduced at the beginning of the war in 1939, had to be continued even under the occupation. Depending on the physical condition or the energy consumption in the work process, food stamps gave authorization to purchase the vital calories - if they were in stock. The illegal black market and the bartering of embezzled products, especially from farmers, were alternative supply options that were pursued by the occupation and the German authorities. In 1946, the completely inadequate supply of food, fuel and material for production and reconstruction caused the Allies - especially the Americans and British - to prevent the total impoverishment of Germany with aid projects and to cut back the reparations payments of their zones to the Soviet Union and France. The Marshall Plan for the economic reconstruction of Europe founded by the USA was one of the most extensive aid programs that also included Germany from 1948. For the French government, the Anglo-American measures to treat Germany as an economic entity to be rebuilt were a breach of the original resolutions and the actual Allied war goal. She reacted by defining her zone (see Bizone - Trizone ). The effects of the division of Europe into East and West brought France back closer to the occupation policy of the Western Allies. With the joint implementation of the currency reform in the summer of 1948, an economic recovery began in the western zones, starting above all with the availability of food and beverages.

Political cleansing ("denazification")

In the Potsdam Agreement of August 1945, the Allies in the “Political Principles” department laid down how Germany should be liberated from Nazism and how war criminals, Nazi activists and members of various Nazi organizations should be treated. A handbook drawn up by the Americans in 1944 with a detailed description of all ranks and job descriptions of Nazi party comrades and officials helped the Allies decide who should be provisionally detained, interned, or dismissed from service until a trial was opened.

In contrast to the Anglo-American purge authorities, the French already involved German anti-fascists and “unencumbered” citizens in the denazification process in 1945. Behind this was a consideration, particularly represented by the head of the occupation administration, General Laffon, of giving the "other Germans", the population groups disadvantaged and oppressed by Nazi rule , a responsibility in the democratization process as a new elite.

The French purge model did not work adequately for several reasons: The initial approval of the population for the denazifications quickly turned into the opposite, because they denied the French the “legitimation of the winner”, the procedures lasted too long, were non-transparent and incomprehensible and punishments were not considered were felt to be appropriate. The widespread opinion after the first judgments of the Nuremberg Trials was that that was enough.

As early as the end of 1945, the military authorities considered rebuilding the economy more important than a comprehensive clean-up. Especially after you could be sure that the predominantly anti-French population did not pose a security threat. The influence of the German authorities became increasingly stronger from 1947 and the number of rehabilitated former National Socialists increased with the necessity to want to become efficient again in the administrations and industry. In December 1949, the last 12 inmates of the Trier internment camp were released.

School, church, culture

The military government ordered the resumption of schooling on October 1, 1945. In many places there were difficulties in conducting regular teaching until 1948 because there were not enough teachers. Almost 75 percent of the German teachers were mostly members of the NSDAP or a related organization. They were therefore released, interned or only employed on a temporary basis. Textbooks from the time of National Socialism could no longer be used. New editions were only issued slowly because there were too few "unencumbered" authors. School buildings were damaged by the war and could only be used to a limited extent or were confiscated by the crew for their own use.

Children and schoolchildren who suffered from malnutrition and poor clothing, especially in the cities, received donations from international, denominational and secular aid organizations. The US organization CARE with its packages has become the collective term for welcome donations. It has been largely forgotten that donations were received from the Free State of Ireland, Sweden and Switzerland as early as December 1945. The German authorities in the French zone set up free school meals from May 1949 , following an initiative by the bizone administration .

In the design of school forms and teaching, the Catholic churches in particular saw themselves in the first post-war years as the politically unsuspicious institution that had a legitimate right to shape it. According to their ideas, schools, teaching and denominational orientation should be brought back to the state of the pre-Nazi era. The basis for this was the Reich Concordat of 1933, which was recognized by the French, but was interpreted more broadly by the German side. For denial against simultaneous school, majority consideration of the local denomination and the corresponding appointment of teachers, four hours of religious instruction per week, gender segregation in the upper level, the churches mobilized parents' resolutions and drafted letters of protest that even occupied the French Foreign Ministry.

"The intellectual attitude of young people of all ages is confused and opaque." Complained the Christian Democratic (CDP) Prime Minister of Rhineland-Palatinate in his first government declaration in 1946 about the school situation in the newly founded state of Rhineland-Palatinate. This statement could also be understood as a criticism of the French model of a state-controlled, secular school system , which the French also considered suitable for their zone. In their opinion, a reform of the German school system was the prerequisite for educating young people to democracy, while the influence of the confessional promotes intolerance and the division of society. The public elementary, middle schools and grammar schools were therefore operated as interdenominational institutions.

The creation of non-denominational teacher training institutes for the elementary levels was an important point in the “réédducation” (re-education) of Germans for the military administration. The Catholic Bishop of Speyer z. In October 1946, after vigorous protests, B. obtained the approval of the military administration to set up Catholic teacher training institutions as well.

The military administration objected to the urgent desire of the church to set up a film inspection center and tighten film censorship. In order to educate young people to “moral personalities”, church authorities had to oppose the lifting of a youth ban on film screenings, such as B. the cinematic classics "Feuerzangenbowle" or "The Blue Angel" protests.

As early as autumn 1945, a range of cultural events and entertainment provided opportunities to distract from everyday needs. The “Überlinger Kulturwoche” in October 1945 was, with the support of the French, one of the first initiatives in the zone, which organized concerts, theater performances and exhibitions. The swift reopening of theaters and cinemas also followed the need for a large French military and civilian population. German films were shown that were not objected to by the censors, as well as the latest French productions with German subtitles. The demonstration was initially performed separately for Germans and French.

The need for a scientific education for future elites demanded a university for the northern zone as well as Freiburg and Tübingen in the southern zone. In February 1946, the military government recommended founding a university in Mainz, which could be a modern alternative to the “Prussian” universities of Bonn and Frankfurt. The 1946 summer semester began with 1,900 students in six fields. The university building was a little damaged, former air force barracks .

broadcast

The first radio transmitter in the French occupation zone was built in an undamaged Koblenz barracks and began broadcasting on October 14, 1945. A short-wave transmitter " Südwestfunk " (SWF) began on October 20, 1945 in Baden-Baden . In 1946 transmitters in Freiburg, Kaiserslautern and Sigmaringen followed. In every station announcement the addition "a station of the military government" was spoken. The programs were initially produced with the cooperation and censorship of the military government. It also brought about the merger of the broadcasters with the main studio in Baden-Baden. By 1947 the broadcasters were expanded and their kW output increased. On January 25, 1947, the first German radio exhibition after 1939 opened in Koblenz. For the first time, a "sound recording and playback device" was presented to the public by tape recording.

After the founding of the Federal Republic of Germany, the broadcaster belonged to the newly founded ARD from June 1950 ; when the state of Baden-Württemberg was re-established in 1952, there were two ARD stations there. The SWF lost its independence in 1998 when it merged with the SDR and the associated re-establishment of the SWR , based in Stuttgart .

The Saarland formed for the project from the immediate post-war period, it in French territory to integrate ( "rattachement" ) , a special zone within the French zone, therefore led the military government in 1945/46 outside their official radio station in Baden-Baden the first "Radio Sarrebruck ”, the former Reichsender Saarbrücken under her aegis, which then went on air as“ Radio Saarbrücken ”with an exclusively German-language program. When the plans for incorporation had to be abandoned under pressure from the rest of the Allies, the station retained its independence from the SWF and on December 31, 1947 received its own director appointed by the French General Government. Due to the historical special route of the Saarland as a partially autonomous state structure from 1949 to 1956, the station continued to exist in the state capital Saarbrücken , after the accession of the Saarland to the Federal Republic in 1957, "Radio Saarbrücken" became the independent ARD company Saarländischer Rundfunk .

Press

In April 1945 the last regional newspapers had ceased to appear. From then on, posters and crier informed the population about the orders of the crew. At the beginning of August 1945 the first press products appeared and ended a period of several months of lack of information and the spread of "false reports, rumors and the formation of legends". In Rhineland-Hesse-Nassau , the northeastern part of the occupation zone, the Middle Rhine Courier appeared in Bad Ems on August 3, 1945 . The newspaper appeared three times a week with a circulation of 300,000 copies. The Mainzer Nachrichten and others appeared only once or twice a week and mostly contained official announcements. At the beginning of 1946, the Badische Illustrierte was the first magazine in the French zone. The rationed allocation of paper and the lack of transport options made daily, scheduled newspaper production impossible until 1948.

Quote on the sources

Quote from the introduction to a processing of documents of the French zone of occupation for the period from March 1945 to August 1949:

“ A comprehensive presentation of the early years of the state of Rhineland-Palatinate based on an intensive study of files is not yet available (...). The files of the State Chancellery [...] show notable gaps [...] minutes of the Prime Minister's Conferences and the discussions with the French There are only gaps in the handing over of occupying powers [...] to talks between Foreign Minister Schuman and representatives of the state government, there are no records [...] There are only a few files from the Ministry of Finance, where the files of the former Ministry of Reconstruction should also be looked for, which have obviously been completely destroyed . "

literature

- Jochen Thies , Kurt von Daak: Southwest Germany Zero Hour. The history of the French zone of occupation 1945–1948. Düsseldorf 1979, ISBN 3-7700-0547-3 .

- Wolfgang Benz , Hermann Graml (ed.): Fischer world history. Volume 35: The Twentieth Century II, Federal Republic of Germany. Fischer Taschenbuchverlag, Frankfurt am Main 1994, ISBN 3-596-60035-9 .

- Peter Brommer (edit.): Sources on the history of Rhineland-Palatinate during the French occupation. State Parliament Commission for the History of Rhineland-Palatinate, Mainz 1985.

- Stefan Martens (Ed.): From “Erbfeind” to “Renewer”: Aspects and motives of the French policy towards Germany after the Second World War. (= Supplement to Francia . Volume 27). Thorbecke, Sigmaringen 1993, ISBN 3-7995-7327-5 . (on-line)

- Knut Linsel: Charles de Gaulle and Germany 1914–1969. (= Supplement to Francia. Volume 44). Thorbecke publishing house, Sigmaringen 1998. (perspectivia.net)

- Wolfgang Fassnacht: Universities at a turning point? - University policy in the French zone of occupation (1945–1949). (= Research on the history of the Upper Rhine region. Volume 43). Alber, Freiburg (Breisgau) / Munich 2000, ISBN 3-495-49943-1 .

- Martin Schieder: Expansion / Integration. The art exhibitions of the French occupation in post-war Germany. (= Passerelles. 3). German Kunstverlag, Munich / Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-422-06414-1 .

- Joachim Groß: The German judiciary under French occupation 1945–1949: the influence of the French military government on the re-establishment of the German judiciary in the French occupation zone. (= Rhenish writings on legal history. Volume 4). Nomos, Baden-Baden 2007, ISBN 978-3-8329-2439-3 .

- Frank Becker: Culture in the shadow of the tricolor: theater, art exhibitions, cinema and film in the French-occupied Württemberg-Hohenzollern 1945–1949. (= European university publications. Series 3: History and its auxiliary sciences. Volume 1041). Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2007, ISBN 978-3-631-56035-8 .

- Joel Carl Welty: The Famine Year in the French Zone 1946–1947. Editing and archival editing of the State Main Archive of Rhineland-Palatinate, Koblenz 1995, ISBN 3-9803142-8-6 .

Web links

- Authority history June 1945–1952 (Württemberg, Baden etc.)

- Source collection: French occupation (Landesarchiv Baden-Württemberg) (no access)

Individual evidence

- ↑ French Provisional Government should be invited to become a member of the Allied Control Council for Germany. wikisource / Yalta Conference Agreement.

- ↑ For the USA, de Gaulle's claims as “an expression of an exaggerated striving for great power” were negligible. After the French surrender in June 1940, Roosevelt had decided “that the United States no longer placed any weight on France.” Knut Linsel, Charles de Gaulle and Germany 1914–1969 cited on p. 96 from de Gaulle's memoirs a conversation between de Gaulle and President Kennedy 1961.

- ↑ K. Linsel: Ch. De Gaulle. P. 111 ff.

- ^ S. Martens: Vom Erbfeind. Francia Supplement Volume 27, p. 10 ff.

- ↑ "une question de vie ou de mort." Was formulated by de Gaulle in his Paris speech on September 12, 1944, quoted by K. Linsel in: Ch. De Gaulle .

- ↑ detail K. Linsel in Conclusion : Ch de Gaulle.. P. 252 ff.

- ↑ K. Linsel: Ch. De Gaulle. P. 116.

- ↑ K. Linsel: Ch. De Gaulle. Press conference in Washington on July 10, 1944 on the occasion of a meeting with US President Roosevelt p. 117.

- ↑ K. Linsel: Ch. De Gaulle. P. 117 and 121.

- ↑ This army was a "motley bunch" (Thies / von Daak) of regular troops with a high proportion of colonial soldiers and members of the Resistance , the Maquis in Thies / von Daak: Südwestdeutschland ..., Der Einmarsch. P. 17 ff.

- ^ Office of the chief of military history US Army, Chronology 1941-1945. P. 443, Washington DC 1960.

- ↑ K.-H. Henke, The American Occupation of Germany. P. 249 ff.

- ↑ Ian Kershaw: The End. Fight to the end. Nazi Germany 1944/45. Munich 2011, p. 417 and note 9

- ↑ Facts and background information on the shooting of the hostages in Reutling in 1945, Reutlinger General-Anzeiger from April 16, 2005, accessed on December 6, 2016.

- ↑ From a regulation of the military commander Mercadier for the Reg.-Bez. Koblenz from July 12, 1945 in: P. Brommer, Quellen zur Geschichte. P. 24.

- ^ From a weekly report to the military government in Neustadt of July 24, 1945, from: P. Brommer, Quellen zur Geschichte. P. 34.

- ^ P. Brommer, Landesregierung Rhld.-Pfalz: Sources. Daily order No. 1 from General Billotte of July 12, 1945 for the Rhineland-Hesse-Nassau area, p. 23.

- ↑ Thies, von Daak: Südwestdeutschland Zero Hour…. P. 29 ff.

- ↑ Ordinance No. 2 on the publication of official gazettes in the French occupied territory of August 22, 1945, published in the official gazette of the French High Command in Germany of September 3, 1945 ( online edition ( Memento of February 15, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) at the Deutsche National library)

- ↑ Wolfgang Benz, Hermann Graml (ed.): Fischer Weltgeschichte, Volume 35, The Twentieth Century II. W. Benz, IV. Federal Republic of Germany. P. 125, Fischer Taschenbuchverlag, Frankfurt am Main 1994.

- ↑ On the other hand, the French. Foreign Minister Robert Schuman : "France was always striving for economic, not constitutional affiliation", minutes of a meeting with representatives of the Rhineland-Palatinate government in Paris on February 20, 1949 at P. Brommer / Landesreg. Rhld.-Pfalz: Sources for history…. P. 740.

- ↑ Management report Reg. Bez. Trier. June 30, 1947 in P. Brommer / Landesreg. Rhld.-Pfalz, p. 480 ff.

- ^ P. Brommer, Landesreg. Rhineland-Palatinate: Sources…. P. 180 and p. 536.

- ↑ Thies, von Daak: Südwestdeutschland Zero Hour…. P. 30 ff.

- ^ Rainer Möhler: Political cleansing in the southwest under French occupation regionalgeschichte.net, accessed on August 26, 2018.

- ↑ Thies, von Daak: Südwestdeutschland Zero Hour…. P. 117.

- ↑ KD Henke: III. France. In: Europe after the Second World War…. Fischer Weltgeschichte Volume 35, p. 108 ff.

- ^ Henry Wilde (Hermann Ebeling): Around the French Zone. In: La Otra Alemania. Issue 134 from January 15, 1947.

- ^ P. Brommer, Landesreg. Rhld.-Pfalz: Sources… Letter dated June 8, 1948. P. 618.

- ↑ Thies, von Daak: Südwestdeutschland Stunden Null, 6. Franz. Demontage- u. Economic policy. P. 110 ff.

- ↑ Thies, von Daak: Südwestdeutschland Stunden Null, 6. Franz. Demontage- u. Economic policy. Pp. 85-94.

- ↑ The Second World War - the climax of the Franco-German “hereditary enmity” (PDF; 184 kB), accessed on November 27, 2012.

- ↑ Thies, von Daak: Südwestdeutschland Zero Hour. P. 140 ff.

- ↑ For the northern part of the zone these were the upper and regional presidents

- ^ P. Brommer, Landesreg. Rhld.-Pfalz: Sources ... Management report for the Reg.-Bez. Koblenz from April 1 to June 30, 1946. p. 182.

- ^ P. Brommer, Landesreg. Rhld.-Pfalz: Sources ... Management report for the Reg.-Bez. Montabaur from July 1 to September 30, 1946. p. 245 ff.

- ^ P. Brommer, Landesreg. Rhld.-Pfalz: Sources ... Management report for the Reg.-Bez. Trier. of June 30, 1947, p. 480 ff.

- ↑ Thies, von Daak: Südwestdeutschland Zero Hour. P. 140 ff.

- ↑ Gabriele Trost. The reconstruction planning of a German city in the French occupation zone: Koblenz 1945 to 1950. Unprinted thesis Paris 1992, p. 8 f.

- ^ According to the resolution of a district council conference in 1945 in: P. Brommer / Landesreg. Rhineland-Palatinate: Sources…. P. 126 ff.

- ↑ The April 1946 monthly report for the city of Landau describes the dramatic supply situation as an example. In: P. Brommer, Landesreg. Rhineland-Palatinate: Sources…. P. 174 ff.

- ^ DocumentArchiv.de: Communication on the tripartite conference in Berlin ("Potsdam Agreement") , accessed on December 1, 2019

- ↑ Detailed treatment of the topic by Rainer Möhler: regionalgeschichte.net and perspectivia.net

- ↑ Thies, von Daak: Südwestdeutschland Zero Hour ... p. 119 ff.

- ↑ Joel-Carl Weltly, Das Hungerjahr ..., with an introduction by Franz-Josef Heyen , Director of the State Main Archive of Rhineland-Palatinate, p. 5 ff.

- ^ P. Brommer, Landesreg. Rhld.-Pfalz: Sources ..., p. 759.

- ^ P. Brommer, Landesreg. Rhld.-Pfalz: Sources ..., p. 679.

- ^ P. Brommer, Landesreg. Rhineland-Palatinate: Sources…. P. 311.

- ^ P. Brommer, Landesreg. Rhld.-Pfalz: Sources ..., p. 370 ff.

- ^ P. Brommer, Landesreg. Rhld.-Pfalz: Sources ..., p. 251.

- ^ P. Brommer, Landesreg. Rhld.-Pfalz: Sources ..., p. 170.

- ↑ Thies, von Daak: Südwestdeutschland Zero Hour ... p. 132 ff.

- ^ P. Brommer, Landesreg. Rhineland-Palatinate: Sources…. P. 151.

- ↑ Thies, van Daak: Südwestdeutschland Zero Hour ..., cultural policy of the French. P. 131 ff.

- ↑ Thies, van Daak: Südwestdeutschland Zero Hour ..., cultural policy of the French. P. 128 ff.

- ↑ From a district administrator's report to the military government of Neustadt / Pfalz from September 17, 1945 in: P. Brommer / Landesreg. Rhld.-Pfalz: Sources for history…. P. 101.

- ↑ Koblenz Contributions to History and Culture , Volume 6, Görres Verlag, Koblenz 1996, ISBN 3-920388-57-7 , p. 161.

- ↑ P. Brommer :, Sources for the history of… Preliminary remark, pp. 1–6.