Potsdam Agreement

The agreements and resolutions made at the Potsdam Conference at Cecilienhof Palace in Potsdam after the end of the Second World War in Europe , which were published in a communiqué of August 2, 1945, are referred to as the Potsdam Agreement . At the conference, among other things, the reparations to be paid by Germany , the political and geographical reorganization of Germany , its demilitarization and the handling of German war criminals were negotiated and established on August 2, 1945.

Participants in this conference were the heads of government of the three victorious powers , i.e. the Soviet Union , the United States of America and the United Kingdom , and their foreign ministers. Initially these were Josef Stalin (Soviet Union), Harry S. Truman (United States) and Winston Churchill (United Kingdom). After the general election was lost , the new Prime Minister Clement Attlee came to the conference on July 28th instead of Churchill .

France was not involved in this conference, but approved the Potsdam resolutions with reservations in six separate letters dated August 7, 1945, each addressed to the three powers. The value of these agreements lies in the fact that, on the one hand, it established that all Allies (the Four Powers ) had overall responsibility for Germany as a whole , and on the other hand, it was agreed that the occupation authorities were to allow democratic political parties and trade unions in Germany .

The validity of the Potsdam Agreement as well as all other “four-sided agreements, resolutions and practices” aimed at Allied “rights and responsibilities in relation to Berlin and Germany as a whole ” was terminated by the Two-Plus-Four Treaty .

Protocol and communiqué

The meeting in Potsdam took place in camera, the press was not permitted. On August 1, 1945, the Protocol of the Proceedings of the Berlin Conference was signed. This document, in which the resolutions, agreements and declarations of intent of the three victorious powers are recorded, is known as the "Potsdam Agreement". A version shortened by eight paragraphs was published immediately after the negotiations ended. This abridged version was published under the title “Communication on the Tripartite Conference of Berlin” in the “Official Gazette of the Control Council in Germany”. The long version was published by the US State Department on March 24, 1947.

Legal character

From a legal point of view, this is not an international treaty , but a joint conference communiqué , a joint declaration of intent or intent. This conference communiqué is usually referred to, factually and legally imprecise, as the Potsdam Agreement.

Its content and scope were controversial, since a clear distinction must be made between political and legal effects.

Content of the protocol

The minutes signed by the negotiating partners include: a. the following points of the conference, which are also known as the so-called Potsdam resolutions :

- Course of the conference

- Establishment of a "Council of Foreign Ministers"

- Principles for the occupation of Germany

- Provisions on reparations

- Viewing Germany as an economic unit

- Disposal of the German war and merchant navy

- Treatment of war criminals

- Regulations on territorial issues regarding the German eastern territories (until the final peace settlement under temporary Polish administration ), Austria and Poland

- Conclusion of peace treaties

- territorial trusteeship (former Italian colonial territories)

- "Proper transfer of the German population or parts of the same who remained in Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary to Germany" (Chapter XIII)

consequences

Council of Foreign Ministers

In order to prepare an international post-war order and peace treaties , the three powers set up a Council of Foreign Ministers to which France and National China should also send a representative. This council met eight times by 1949 for conferences. Only once, in London in 1945 , were all five great powers represented. However, the Soviet Union protested against the participation of China and France in the peace settlement for Eastern Europe . The task of reaching an agreement on the post-war order at these foreign ministerial conferences was only carried out to a limited extent because the plans of the great powers were incompatible. Soviet policies in East Asia , the Middle East and Eastern Europe ran counter to US interests , which eventually led to a confrontation between the western and eastern camps.

Political principles

The political principles for the occupation of the German Reich were practically a work instruction for the Allied Control Council in Berlin. They are also referred to as the "4 D ":

- D enazifizierung (also: denazification)

- The denazification was an initiative of the Allies after their victory over the Nazi Germany in mid 1945. Affirms by the Potsdam agreement should be a "cleansing" of the German and Austrian society, culture, press, economy, jurisdiction and politics from all influence of Nazism done.

- For Germany, the Control Council in Berlin passed a large number of denazification directives from January 1946, by means of which certain groups of people were defined and then subjected to a judicial investigation.

- D emilitarisierung (also: demilitarization)

- The aim of demilitarization or demilitarization was the complete dismantling of the army and the abolition of any German armaments industry so that Germany could never again run the risk of a military attack.

- Due to the Cold War and the related mutual threats, however, both German states felt compelled to rearm within the framework of their alliances . For this purpose, arms production was resumed in the Federal Republic of Germany and the Bundeswehr and in the GDR the National People's Army (NVA) were founded.

- See also: Conversion (conversion of military facilities)

- D emokratisierung

- The final transformation of German political life on a democratic basis should be prepared and all democratic parties and trade unions should be allowed and promoted throughout Germany.

- With military security in mind, freedom of speech, press and religion was granted.

- The education system in Germany should be monitored in such a way that a successful development of democratic ideas is made possible.

- D ezentralisierung

- The aim of decentralization was to transfer political tasks, responsibilities, resources and decision-making powers to middle (e.g. provinces, districts, regions) and lower levels (cities, municipalities, villages). In the economy, the excessive concentration of power such as in cartels, syndicates, large corporations and other monopoly business enterprises should be eliminated.

- See also: Political Level , Political System of Germany

Territorial decisions

North East Prussia (today "Oblast Kaliningrad")

The 1946 Administrative Region created today to Northwest Russia belongs Kaliningrad region was as northern East Prussia with the provincial capital Konigsberg conquered by the Soviet Union and several months before the Potsdam Conference by a constitutional amendment in their territory integrated; After all German place names were Russified , the area was incorporated into the RSFSR by the constitutional law of February 25, 1947 as an administrative unit ( Oblast ) under the name "Autonomous Oblast Kaliningrad" .

In the Potsdam Agreement, Article VI on the "City of Königsberg and the Adjacent Area", it is stated that the "[...] western border of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics [which] borders the Baltic Sea from a point on the eastern coast of the Gdańsk." Bay in an easterly direction north of Braunsberg-Goldap and from there to the intersection of the borders of Lithuania , the Polish Republic and East Prussia. ”At the request of the Soviet Union to hand over this northern part of East Prussia, the President of the USA Truman and British Prime Minister Attlee in the Conference Communiqué, Section VI, to support the Conference proposal at the forthcoming Peace Conference (Section VI).

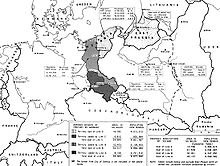

Poland and the provisional Oder-Neisse border

The question of which territory Poland should be granted was also discussed at the Potsdam conference. In the meantime, a new Polish government had emerged from the Lublin Committee, which was sponsored by Stalin, supplemented by some Poles in exile in June 1945, and was therefore recognized by the Western Powers before the Potsdam Conference. It was obvious that Poland would be a satellite state of Moscow and that its government had little legitimacy. Free and democratic elections were assured in formulaic declarations that all Poles in exile should be able to return soon.

Lausitzer Neisse or Glatzer Neisse

Faced with a fait accompli, the two western allied victorious powers also accepted the Polish administration of these areas until a peace treaty was settled . At first it was also disputed whether the border should be drawn along the Lusatian Neisse or Glatzer Neisse . It is rumored that the American and British negotiating delegations were initially unaware of the existence of the Lausitz Neisse. Of these, instead of the Oder-Neisse Line , the Oder- Bober Line (better: Oder-Bober- Queis Line) 50 kilometers further east was brought into play as the German eastern border, but the Soviet Union refused to approve it. After this plan became known, the Polish communists were the first to drive the native Germans out of this area between Bober-Queis and the western Neisse with particular brutality before the conference. Such a regulation would at least have left eastern Lusatia completely with Germany and avoided the division of cities like Görlitz and Guben . Ultimately, an agreement was reached on the Lusatian Neisse. The final document says: “The heads of the three governments agree that until the final determination of the western border of Poland, the formerly German areas east of the line, that of the Baltic Sea immediately west of Swinoujscie and from there along the Oder to the confluence of the runs along the western Neisse and the western Neisse to the Czechoslovak border, including that part of East Prussia which is not placed under the administration of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in accordance with the agreements reached at this conference and including the area of the former Free City of Danzig the administration of the Polish state come and in this regard should not be regarded as part of the Soviet occupation zone in Germany. "

Szczecin

After the Potsdam Conference approved the border over the Lusatian Neisse, at least the Oder should be used as the border river. On July 5, 1945, the Soviet Union had placed the city of Stettin west of the Oder and the approximately 84,000 Germans still living there under the Polish administration. The possession of Szczecin and the mouth of the Oder in the Szczecin Lagoon represented an economic demand for Poland to take possession of the Upper Silesian industrial area .

At the conference no concrete definition of the northernmost border section at and seaward from Szczecin was made. However, the Western Allies and the Soviet Union were politically in agreement that the port of Szczecin should be added to Polish territory. In principle, there was consensus between the victorious powers and "according to the (Cohen) minutes of the meeting of July 31, 1945 [...] no doubt [...] about the assignment of Szczecin to the Polish administrative territory".

On September 21, 1945, a Soviet-Polish agreement was signed, “through which the demarcation between the Soviet occupation area on the one hand and the Polish administrative area on the other, which is now the borderline, the entire so-called ' Stettiner Zipfel ' [came] comprehensive, advanced far to the west. ”This agreement for the unilateral“ formal ”fixation of the border in the Swinoujscie - Greifenhagen section “ at the expense of Germany ”was based on a sine qua non , as Poland's eastern border was on the Curzon line and thus considerably to the west was returned. To this day, along with other documents from 1945, it is "fundamental to the actual course of the border [...]" which was finally used in the later German-Polish treaties ( 1950 , 1970 and 1990 ) to determine the border between Germany and Poland.

Forced relocations and evictions

Together with those who had fled westward from the advancing Red Army since 1944 , more than twelve million people lost their homes as a result of flight and displacement by the Polish militia and locally trained Polish administrative authorities. As early as the summer of 1941, the Polish and Czechoslovak government- in- exile in London demanded border adjustments after the victory over National Socialist Germany within the framework of international legal norms and, by signing the Atlantic Charter , assured that they would not assert any territorial claims beyond this. In disregard of the Atlantic Charter, the three victorious powers represented at the Potsdam Conference, however, expressly "approved" the forced resettlement of the German population from traditionally German-populated areas. Unlike under the Treaty of Versailles in 1920 or the population exchange in South Tyrol from 1939 to 1943 , the resident Germans were not given an option to opt for another nationality . The well-known XIII. In this context, the article only speaks of the “transfer” of Germans from Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary, ie not from the German Reich territory .

In fact, the affected German settlement areas included:

- in present-day Poland southern East Prussia with the regions of Masuria and the Oberland ; Western Pomerania with Stettin and the Oder delta ; Neumark Brandenburg , Grenzmark Posen-West Prussia , Lower Silesia and West Upper Silesia as well as areas that have been denied to the German Reich since 1919 , but in which many Germans still lived: Province of Posen , East Upper Silesia , Kulmerland and also Pomerania , from which the Free City of Danzig and the Polish Corridor was created;

- in Czechoslovakia the Sudetenland as well as Prague and the German-speaking islands in Central Bohemia and Moravia ;

- in Hungary numerous cities and scattered German settlements.

The transfer should be "done in an orderly and humane manner". At the same time, the Czechoslovak and Polish Provisional Governments and the Allied Control Council in Hungary are requested to suspend further deportations until the Western Allies have determined the reception capacity in the West.

At the time of the German surrender, an estimated half of the former 15 million Germans were still living in the planned displacement areas. Flight and expulsion began before the Potsdam Agreement was signed, and thousands were killed in the winter of 1944/45. Around 600,000 Germans and people of German origin are estimated to have died between 1944 and 1947 while fleeing or being expelled. Private property of the East and Sudeten Germans and property of German churches in these areas were confiscated as reparations by Poland and Czechoslovakia . By the end of the 1950s, around four million German or ethnic Germans had migrated to the two German states that were being established as an indirect consequence of these expulsions .

Those responsible were aware that a future peace treaty settlement would have little room for maneuver than to recognize the status it had created. The Western Allies did not initially oppose the Soviet struggle for power, which was later made possible by the Berlin blockade , for example .

Reorganization of the political situation

In contrast to the Treaty of Versailles , the scope for decision-making was very limited. The Potsdam resolutions also did not constitute a peace treaty in the sense of international law. The agreement of the three heads of government was a quick agreement with far-reaching consequences for the heterogeneous anti-Hitler coalition through the endeavor to create a fait accompli.

criticism

The alleged legitimation of the ongoing expulsions of the German civilian population from the eastern areas was later sharply criticized. The West was also angry about the looting , the removal of goods, the mass arrests and finally the sexual assault by Soviet troops, which killed around 240,000 women during this time. Rudolf Augstein wrote about the Potsdam Conference:

“The ghostly thing about the Potsdam Conference was that a war crimes tribunal was decided by victors who, according to the standards of the later Nuremberg Trial, should all have been hanging. Stalin at least for Katyn , if not at all. Truman for the completely superfluous bombing of Nagasaki , if not for Hiroshima , and Churchill at least as the head bomber of Dresden , at a time when Germany was already done for. All three had decided on so-called ' population relocations ' of insane proportions, all three knew how criminal it was. "

The division of Germany into zones of occupation and the allied control procedure were confirmed and specified. US Secretary of State Byrnes proposed this (the partition of Germany ) on the afternoon of July 31, 1945. Regarding the territorial design of the occupation zones, the proposals of the European Advisory Commission (EAC) were followed, but France was promised its own zone , which was formed from parts of the British and American zones.

The decision at the Potsdam Conference to divide Germany as a reparations area, that is to say to allow every occupying power to enforce its own interests in reparation payments in their respective zone, was extremely momentous. This decision was made because the Western powers, which pursued moderate reparations policies, could not come to an agreement on reparations issues with Stalin, who took a very tough line.

The compromise formula was ultimately drawn up so as not to let the conference, which had not produced any significant results, fail completely.

The historian Hermann Graml wrote about this decision :

"Although the Americans and the British were allowed to say to each other that with the division of the reparations area they had created the basis for a rational reparations policy in the western zones of occupation , they could not hide from themselves that the economic liberation of the western zones - that was basically the point - at the expense of the inhabitants of the Soviet zone, who now had to satisfy the Soviet reparation claims almost alone and so, according to human foresight, were handed over to a far more brutal policy of plunder and exploitation than they otherwise had to face. "

As a result, the German economic entity collapsed, which was also due to the French obstruction in the Allied Control Council; soon afterwards - in the wake of the beginning of the Cold War - also the political one.

With regard to the Pacific War , the Potsdam Declaration of July 26, 1945 laid down the official American-British-Chinese conditions for the surrender of the Japanese Empire . The Potsdam Declaration was formulated by President Harry S. Truman and Prime Minister Winston Churchill during the Potsdam Conference and co-signed by telegram by Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek .

See also

literature

- Wolfgang Benz : Potsdam 1945. Occupation and rebuilding in four-zone Germany . dtv, Munich 2012, ISBN 3-423-04522-1 .

- Milan Churaň: Potsdam and Czechoslovakia . Working group of Sudeten German teachers and educators Dinkelsbühl, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-9810491-7-6 .

- Fritz Faust: The Potsdam Agreement and its significance under international law , Metzner (4th [greatly expanded] edition), Frankfurt am Main / Berlin 1969.

- Charles L. Mee : The Division of the Booty. The Potsdam Conference 1945. Fritz Molden, Vienna [u. a.] 1977 (Original title: Meeting at Potsdam [From d. America. translated by Renata Mettenheimer]), ISBN 3-217-00706-9 .

- Wenzel Jaksch : Europe's way to Potsdam. Guilt and Fate in the Danube Region. Langen Müller, 1990.

- Heiner Timmermann (Hrsg.): Potsdam 1945. Concept, tactics, error? (= Documents and writings of the European Academy Otzenhausen Vol. 81; EAO 81). Duncker and Humblot, Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-428-08876-X .

- Charles L. Mee : The Division of the Booty. The Potsdam Conference 1945. Fritz Molden, Vienna 1975 (original title: Meeting at Potsdam , translated by Renata Mettenheimer), ISBN 3-453-48060-0 .

- Potsdam Papers. Foreign Relations of the United States - Diplomatic Papers - The Conference of Berlin (The Potsdam Conference) 1945 . Two volumes. Washington, DC 1960.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ For the wording of the letters cf. Documents on Germany Policy (DzD) II / 1, pp. 2213–2218; EUROPA ARCHIVE 1954, pp. 6744-6746.

- ↑ Quotation from Article 7, Paragraph 1 of the Treaty on the final regulation with regard to Germany .

- ↑ Cf. Dieter Blumenwitz : The contract of September 12, 1990 on the final regulation with regard to Germany , NJW 1990, pp. 3041, 3047 .

- ↑ Supplement to the AJIL, Official Documents 1945, pp. 245 ff.

- ^ German text of both documents in: Michael Antoni : The Potsdam Agreement, Trauma or Chance? Validity, content and legal significance , Berlin 1985, ISBN 978-3-87061-287-0 , pp. 340–353.

- ^ Boris Meissner, The Potsdam Conference. In: Boris Meissner u. a. (Ed.): The Potsdam Agreement. Part 3: Looking back after 50 years. Vienna 1996, p. 12 (Discussions on International Law, Vol. 4).

- ↑ Wilfried Fiedler , The international legal precedent effects of the Potsdam Agreement for the development of general international law , in: Heiner Timmermann (Ed.): Potsdam 1945 - Concept, Tactics, Error? , Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1997, p. 297 (documents and writings of the European Academy Otzenhausen, vol. 81).

- ↑ See JA Frowein , Potsdam Agreements on Germany (1945) , in: Bernhardt (ed.), Encyclopedia of Public International Law (EPIL), Inst. 4 , 1982, pp. 141 ff.

- ↑ J. Hacker, Introduction to the Problems of the Potsdam Agreement , in: F. Klein, B. Meissner (eds.): The Potsdam Agreement and the Germany Question, Part I , 1970, p. 13 ff .; ders., Soviet Union and GDR on the Potsdam Agreement , 1968, p. 33 ff.

- ↑ "Complete disarmament and demilitarization of Germany and the elimination of the entire German industry, which can be used for war production or its monitoring." - "The complete disarmament and demilitarization of Germany and the elimination or control of all German industry that could be used for military production. " Agreements of the Berlin (Potsdam) Conference, July 17 – August 2, 1945 .

- ^ "At the earliest practicable date, the German economy shall be decentralized for the purpose of eliminating the present excessive concentration of economic power as exemplified in particular by cartels, syndicates, trusts and other monopolistic arrangements." Agreements of the Berlin (Potsdam) Conference , July 17 – August 2, 1945 .

- ^ Thomas Schmidt: The foreign policy of the Baltic states. In the field of tension between East and West. Westdeutscher Verlag, Wiesbaden 2003, p. 170 .

- ↑ a b Communication on the Tripartite Conference in Berlin ("Potsdam Agreement") of August 2, 1945

- ↑ See Daniel-Erasmus Khan , Die deutscher Staatsgrenzen. Legal history basics and open legal questions. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2004, chap. V.II.1.c, p. 323 ff.

- ^ So Daniel-Erasmus Khan, The German State Borders. Legal history basics and open legal questions. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2004, p. 325 .

- ↑ Khan, Die deutscher Staatsgrenzen , Tübingen 2004, quotation p. 327 .

- ^ So Khan, Die deutscher Staatsgrenzen , Tübingen 2004, p. 327 with further references.

- ↑ Georg Dahm , Jost Delbrück and Rüdiger Wolfrum : Völkerrecht , Vol. I / 2: The state and other subjects of international law; Spaces under international management. 2nd edition, de Gruyter, Berlin 2002, ISBN 978-3-11-090695-0 , p. 68 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Deutsches Historisches Museum : Mass exodus 1944/45

- ↑ See Jan M. Piskorski , Die Verjagt. Flight and Expulsion in Europe in the 20th Century , Siedler, Munich 2013, pp. 1947 f .; Michael Sontheimer , Churchill's matches , in: Annette Großbongardt, Uwe Klußmann, Norbert F. Pötzl: The Germans in Eastern Europe. Conquerors, settlers, displaced people. A SPIEGEL book , DVA, 2011; Jens Hacker, Soviet Union and GDR on the Potsdam Agreement , Verlag Wissenschaft und Politik, 1968, p. 31.

- ↑ Hans-Joachim Torke: Introduction to the history of Russia. Beck, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-406-42304-3 , p. 222 .

- ^ Helke Sander , Barbara Johr (eds.), BeFreier und Befreite: War, Rape, Children , Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2005, ISBN 3-596-16305-6 .

- ↑ Rudolf Augstein: On the inclined plane to the republic , Der Spiegel 2/85, p. 30.

- ^ Hermann Graml: The Allies and the division of Germany. Conflicts and decisions. 1941-1948. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1985, ISBN 3-596-24310-6 , p. 99 ff.