Curzon line

The Curzon Line (named after the then British Foreign Minister George Curzon ) was proposed as a Polish - Russian demarcation line after the First World War on December 8, 1919 in Paris with reference to the mother tongue of the respective majority population .

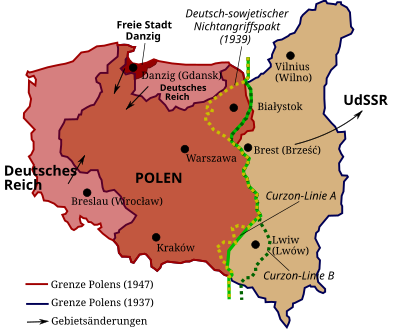

Green Line : Curzon Line, based on the ethnographic principle, proclaimed by the Western Allies on December 8, 1919 as the demarcation line between Soviet Russia and the Second Republic of Poland.

Blue Line : after the end of the First World War until 1922 through the conquests of Poland under General Józef Piłsudski (Galicia 1919, Volhynia 1921 and Vilnius area 1922) across the Curzon Line, which lasted until September 17, 1939.

Yellow line : German-Soviet demarcation line from September 28, 1939.

Red line : today's state border of Poland; left the Oder-Neisse line.

Brown area : area expansion carried out by Poland after the end of the First World War until 1922, which had previously been recognized by the Soviet Union.

Pink area : Eastern areas of the German Reich asserted by Stalin in 1945 for Poland as compensation for the loss of the areas east of the Curzon Line (" west shift ").

Starting position

Immediately after the First World War, the question of the political border of the Polish state, which was re-established in 1918, was initially largely open. The intergovernmental border between Poland and Germany , recognized under international law , was largely determined by the Versailles Peace Treaty; the demarcation of East Prussia and Upper Silesia was to take place after referendums . However, the question of Poland's eastern border remained open. According to the peoples' right to self-determination, it seemed obvious to choose the (mother) linguistic majority as the criterion for defining the border against Soviet Russia, i.e. to draw the eastern border of Poland according to its ethnographic border, which the Polish politician Roman Dmowski in particular had long demanded - albeit with regard to the annexation of German territories that he is striving for . The Western Allies shared this view when, on December 8, 1919, they proclaimed the Curzon Line as a provisional demarcation line between Poland and Soviet Russia. The name "Curzon Line" was only given to the demarcation line in July 1920 after it had been proposed as an armistice line by the British Foreign Minister Lord Curzon in the Spa Protocol in connection with the Allied armistice negotiations in the Polish-Soviet War . The British government assured the Moscow negotiator Lev Kamenev , sent to London, that it would support the Soviet demands for the areas east of this line.

But neither all Poles nor Russia accepted the proposal to draw the border. Incompatible with the proposed border of the Curzon Line was Józef Piłsudski's ( Międzymorze ) federation concept , which envisaged the restoration of Poland-Lithuania within the borders that existed before the partitions . Piłsudski's concept of the Polish-Lithuanian-Belarusian-Ukrainian federation was opposed to a variety of interests (national interests or nationalism of Lithuania , Belarus , Ukraine and Great Russians , Lenin's concept of the world revolution ). Under Piłsudski, Poland's eastern border was moved far beyond the Curzon Line to the east until 1923: in 1919 Eastern Galicia , in 1921 Volhynia and in 1920/22 the Vilna area was taken militarily.

In the areas conquered by Poland, which had belonged to the Polish-Lithuanian state until 1772 and 1795 , the population of Polish origin was in the minority. In the Russian Governorate of Vilnius, for example, the Polish population was only 8.2% in 1897, while Belarusians made up 61.2%, Lithuanians 17.6% and Jews 12.8%; In Volhynia, the Poles made up 6.2% of the population in the same year, while the remaining population was 73.7% Russians (predominantly Belarusians), 13.2% Jews and 5.7% Germans. In 1900, in the whole of Galicia, the Polish part of the population made up 54.75% and the Ruthenian part 42.20%; in western Galicia the Poles formed the majority and in eastern Galicia the Ruthenians. The remaining population of Galicia consisted of Germans, Czechs , Moravians and Slovaks .

According to an estimate by the British daily The Times from 1944 , 2.2 to 2.5 million Poles lived in 1931 in the areas east of the Curzon Line, the so-called Kresy . Of these Poles, 2.1 million are said to have moved west after the Second World War and two thirds of them settled in the “ new areas ”, where they then displaced the indigenous population.

On July 17, 1920, Soviet Russia had proposed a far more favorable border east of the Curzon Line to Poland, arguing that the Curzon Line had been established partly under the pressure of anti-Polish, imperialist demands from the Russian "whites" supported by the Allies .

In the Polish-Soviet War 1919–1921, which ended with the Peace of Riga , neither Poland nor Soviet Russia were able to achieve their war aims. Soviet Russia failed to expand its sphere of influence to the west, but the Polish goal of restoring Poland-Lithuania to the pre- partition borders was not achieved either. Nevertheless, the border was set far east of the Curzon Line.

The current course of Poland's eastern border largely corresponds to the Curzon Line proposed in 1919.

A line

The “A” version of the Curzon Line runs roughly from the southern end of Lake Wystiter to the southeast, then just before Hrodna ( Grodno ) to the south, runs along the Bug River and finally bends to the southwest until the Bieszczady reaches near the Lupka Pass becomes.

The German-Soviet non-aggression pact and the German-Soviet border and friendship treaty were based on the course of the border line proposed after the First World War ; there were some deviations in favor of the Soviet Union ( Białystok region ).

B line

The Curzon line "B", which was also proposed by Roosevelt in 1945 as the eastern border of Poland, was similar to the Curzon line of the A version, but left Lemberg and Drohobycz on the Polish side.

Just west of this line (in Central Poland) dominated by far Poland . At the same time, about 1.5 million Ukrainians lived west of the Curzon Line between Warsaw and Lublin. In the areas east of it the Ukrainians and Belarusians made up the majority; But there were also many Poles living there (according to the Polish census of 1919 about 25%, after Piłsudski's tenure in 1936 about 36% of the population). Many citizens of the Jewish faith lived in the cities, while the rural population was predominantly Russian or Ukrainian Orthodox.

Second World War

In the German-Soviet border and friendship treaty of September 28, 1939, the dividing line roughly corresponded to the Curzon line; the Soviet Union was able to reclaim the areas east of the line in 1939 , as had been planned in 1919. Throughout the course of World War II, the British government consistently believed that Poland's eastern border should be based on the Curzon Line after the end of the war. At the Tehran Conference , Churchill and Roosevelt finally agreed to Stalin's call for the Curzon Line as the new Polish eastern border.

As a post-war settlement, the Allied heads of state Franklin D. Roosevelt (USA), Winston Churchill (United Kingdom) and Josef Stalin (USSR) agreed at the Yalta Conference (February 4 to 11, 1945) a limit that, with some perks, approximated in favor of Poland corresponded to the Curzon A line. The Polish government did not participate in the conference - neither the London government in exile nor the pro-Soviet Lublin government .

During and after the Second World War, in addition to the genocide of Jewish and Slavic residents before 1945, after 1945 there was harassment of ethnic minorities, especially Poles from the areas east of the Curzon Line through the Soviet Union and Ukrainians west of the Line through Poland (e.g. as part of the Vistula action ).

literature

- Kordan Bohdan: Making Borders Stick. Population Transfer and Resettlement in the Trans-Curzon Territories, 1944-1949 . In: International Migration Review. 31 (1997), No. 3, pp. 704-720.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Paul Roth : The emergence of the Polish state - an international law-political investigation (= public law treatises. Ed. By Heinrich Triepel , Erich Kaufmann and Rudolf Smend . 7th issue). Verlag Otto Liebmann, Berlin 1926, in particular pp. 133-142.

- ^ Gotthold Rhode : Brief history of Poland. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1964, p. 466 ff.

- ^ Ellinor von Puttkamer : The Curzon Line as Poland's eastern border. In: Die Wandlung , Volume 2, 2nd issue (April 15, 1947), Lambert Schneider Verlag, Heidelberg, pp. 175-183.

- ↑ Andrzej Nowak: Pierwsza Zdrada Zachodu. 1920 - Zapomniany appeasement. Warsaw 2015, pp. 355–359.

- ↑ a b Wilna Gouvernement ( encyclopedia entry), in: Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon . Volume 20, 6th edition, Leipzig / Vienna 1909, pp. 655–656.

- ↑ a b Wolhynien ( encyclopedia entry), in: Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon , 6th edition, Volume 20, Leipzig / Vienna 1909, pp. 734–735.

- ^ Galizien ( encyclopedia entry), in: Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon , 6th edition, Volume 7, Leipzig / Vienna 1907, pp. 272–275.

- ↑ The Times of January 12, 1944, quoted from Alexandre Abramson (Alius): The Curzon Line . Europa Verlag, Zurich 1945, p. 45.

- ↑ Jörg-Detlef Kühne : Possibilities for changing the Oder-Neisse Line before 1945 . 2nd edition, Nomos, Baden-Baden 2007, footnote 2.

- ^ Manfred Alexander: Small history of Poland . 2nd edition, Reclam, Stuttgart 2008, p. 321.

- ↑ Potjomkin (Ed.): Geschichte der Diplomatie , III-1, Berlin 1948, pp. 99 and 104.

- ^ Ludwik Gelberg: The emergence of the People's Republic of Poland. International law problems (translated from Polish by Barbara Bönnemann-Wittek), Atnenäum Verlag, Frankfurt / M. 1972, ISBN 3-7610-2614-5 , p. 86.

- ^ Jerzy Lukowski, Hubert Zawadzki: A concise history of Poland. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2001, ISBN 0-521-55109-9 , p. 238.