Hepatitis C.

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| B17.1 | Acute viral hepatitis C |

| B18.2 | Chronic viral hepatitis C. |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

The Hepatitis C is a by the Hepatitis C virus infection caused disease in humans. It is characterized by a high rate of chronification (up to 80%), which can lead to severe liver damage such as cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma . It is transmitted parenterally via blood. Treatment of chronic hepatitis C, i.e. complete virus elimination, is not possible in most cases. A vaccine against hepatitis C does not yet exist.

Pathogen

The hepatitis C virus (HCV) was identified for the first time in 1989 with the help of genetic engineering (detection of genetic material) (previously hepatitis non-A non-B). It is a 45 nm enveloped single (+) stranded RNA virus and belongs to the genus Hepacivirus of the Flaviviridae family . There are seven genotypes and 67 subtypes . For example, genotypes 1, 2 and 3 are predominantly found in Europe and the USA and type 4 in Africa. Until now, it was assumed that humans are the only natural hosts of the hepatitis C virus. While searching for the origin of the pathogen in rodents, an international team of scientists found many variants of HCV-like viruses. Antibodies against the pathogen could be detected in bats. Therefore, it is now believed that this family of viruses originally evolved in rodents.

transmission

In about 30% of the diseases, the path of infection can no longer be traced in retrospect . Today, there is an increased risk of infection for users of drugs such as heroin , who use intravenous injection and share the same syringes with other users, as well as for people who use nasal drugs through shared use of (sniffing) tubes. Also, tattoos and piercings are using contaminated instruments is a risk factor. Frequent routes of infection are injuries with pointed and sharp instruments ( needle stick injuries (NSV)) with simultaneous transmission of contaminated blood. The risk of infection after NSI with a known positive index person is given in the literature as 3 to 10 percent. It is thus higher than the average risk of transmitting HIV , but, as with HIV, appears to be heavily dependent on the viraemia of the index person.

Haemophilia patients who were dependent on donor blood / plasma or on coagulation preparations made from human blood, for example, for surgical interventions were also affected . At that time, hepatitis C and B were often passed on to these patients without being noticed. With the introduction of modern test procedures, with the help of which today over 99% of hepatitis C-positive donors can be identified, there is only a minimal risk of infection through blood transfer. Another possible route of infection is a liver transplant.

Sexual transmission of hepatitis C is rare. Because the virus is transmitted through blood, sexual practices that have a higher risk of mucosal injury, such as unprotected anal intercourse , are at higher risk. The frequency of transmission of the virus from the pregnant mother to the unborn child is estimated to be less than 5% in the case of an uncomplicated delivery. In the event of co-infection with the HI virus , the transmission can increase up to 14%.

The incubation period is between 2 and 26 weeks (6 months).

Epidemiology

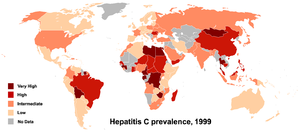

The prevalence worldwide is 2.6%, in Germany 0.5% and in the high-risk areas of the world (dark red areas on the map) 5.0% and more - in Mongolia up to 48%.

The Robert Koch Institute (RKI) publishes figures on the epidemiological situation of hepatitis C every year . For the year 2005 these amount to 8308 registered first diagnoses in Germany. A little more than 50% of these were determined by laboratory diagnostics and had no typical clinical picture. Laboratory diagnostics cannot distinguish between acute and long-standing HCV infections.

Around 170 million people worldwide are infected with the HC virus, in Germany 400,000 to 500,000 people are affected. The main risk group for HCV infection is intravenous drug users, 60 to 90 percent of whom are carriers of HCV. Conversely, in a US study, 48.4% of all anti-HCV-positive people between the ages of 20 and 59 had intravenous drug use.

The number of cases reported to the RKI for Germany has developed as follows since 2000:

| year | reported case numbers |

|---|---|

| 2000 | 5091 |

| 2001 | 4350 |

| 2002 | 6698 |

| 2003 | 8762 |

| 2004 | 8955 |

| 2005 | 8357 |

| 2006 | 7560 |

| 2007 | 6867 |

| 2008 | 6223 |

| 2009 | 5431 |

| 2010 | 4998 |

| 2011 | 5056 |

| 2012 | 4996 |

| 2013 | 5168 |

| 2014 | 5825 |

| 2015 | 4872 |

| 2016 | 4422 |

| 2017 | 4733 |

| 2018 | 5899 |

| 2019 | 6633 |

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is made by detecting virus-specific antibodies against structural and non-structural proteins using enzyme immunoassays and immunoblots, as well as detecting parts of the virus genome (HCV-RNA) using the polymerase chain reaction ( RT-PCR ). If there is a definitely positive antibody test and a multiple negative PCR at an interval of at least three months, it can be assumed that the infection healed earlier. A liver biopsy or a liver sonography can make reliable statements about the stage of the disease (stage of tissue damage). In contrast to other hepatitis, the transaminase values in the blood (GGT, GPT , GOT ) are often independent of the severity or stage of the disease and are therefore not a reliable marker for the actual course of the disease.

course

Hepatitis C is often not diagnosed in the acute phase due to the mostly symptom-free or low-symptom course (in 85% of cases). Possible complaints after an incubation period of 20 to 60 days are tiredness, exhaustion, loss of appetite, joint pain, feeling of pressure or tension in the right upper abdomen, and possibly weight loss. Jaundice develops in some people ; the urine may be very dark and the stool clay-colored. In many cases, the affected person does not perceive the illness at all or only perceives it as a supposed flu-like infection . However, the acute phase turns into a chronic form in more than 70% of the cases. Due to the high variability of the virus and the probably specific suppression of a sufficient T cell response, the virus is constantly replicating and thus causing a chronic infection.

If the infection remains untreated, it will lead to cirrhosis of the liver in about a quarter of patients in the long term after about 20 years . There is also an increased risk of liver cell carcinoma .

In the course of a chronic HCV infection, further, mostly antibody-mediated diseases can occur. These include cryoglobulinemia (particularly common in genotype 2), Sjogren's syndrome , panarteritis nodosa and immune complex glomerulonephritis . In the established causal connection with HCV infection, the extrahepatic diseases described are insulin resistance / diabetes mellitus, cryoglobulemia vasculitis, lymphoproliferative diseases, impaired performance (tiredness, fatigue) and depressive symptoms.

therapy

Standard therapy and therapy algorithms

According to the standard therapy applied in 2009, acute hepatitis C was treated virostatically with PEG-interferon alpha 2-b together with ribavirin after a three-month waiting period and continued positive HCV-RNA result, similar to chronic hepatitis C. Alternatively, the immediate administration of interferon alone over a period of six months could also be considered.

As a standard treatment for HCV genotypes 1 and 4 was 2015 combination of sofosbuvir and Ledipasvir ( Harvoni ® ), for HCV genotypes 2 and 3, a combination of sofosbuvir and ribavirin for HCV genotypes 5 and 6, a combination of Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir and ribavirin, or a combination of daclatasvir and sofosbuvir is recommended as an alternative for HCV genotype 3 .

The "current recommendation for the therapy of chronic hepatitis C" of the German Society for Gastroenterology, Digestive and Metabolic Diseases (DGVS) names as "approved drugs" for the therapy of hepatitis C (status: 7/2015):

- conventional therapy:

- Peginterferon α for initial and re-therapy for all genotypes

- Ribavirin as a combination therapy for initial and re-therapy for all genotypes

- Protease inhibitors:

- Simeprevir ( Olysio ® from Janssen Pharmaceutica ) as a combination therapy for initial and re-therapy for genotypes 1 and 4

- Paritaprevir (pharmaceutical company: AbbVie ) as a combination therapy for initial and re-therapy for genotypes 1 and 4

- Asunaprevir , ciluprevir , danoprevir , glecaprevir , grazoprevir , narlaprevir , sovaprevir , vaniprevir , voxilaprevir

- no longer recommended as standard therapy:

- Telaprevir (EU: Incivo ® , Marketing Authorization Holder : Janssen-Cilag , USA: Incivek ® , Marketing Authorization Holder : Vertex Pharmaceuticals ) as a combination therapy for initial and re-therapy for genotype 1

- Boceprevir ( Victrelis ® , pharmaceutical company: MSD Sharp & Dohme ) as a combination therapy for initial and re-therapy for genotype 1

- Faldaprevir , vedroprevir

- NS5A inhibitors:

- Daclatasvir ( Daklinza ® , pharmaceutical company: Bristol-Myers Squibb ) as a combination therapy for initial and re-therapy for genotypes 1 - 6

- Ledipasvir (pharmaceutical company: Gilead Sciences ) as a combination therapy for initial and re-therapy for genotypes 1, 3, 4 and 6

- Ombitasvir (pharmaceutical company: AbbVie) as a combination therapy for initial and re-therapy for genotypes 1 and 4

- Elbasvir , Odalasvir , Pibrentasvir , Ravidasvir , Ruzasvir , Samatasvir , Velpatasvir

- Non-nucleoside polymerase (NS5B) inhibitors:

- Dasabuvir (EU: Exviera ® , Marketing Authorization Holder : AbbVie) as a combination therapy for initial and re-therapy for genotype 1

- Beclabuvir , Deleobuvir , Filibuvir , Setrobuvir , Radalbuvir , Uprifosbuvir

- Nucleos (t) idic polymerase (NS5B) inhibitors:

- Sofosbuvir ( Sovaldi ® , pharmaceutical company: Gilead Sciences) as a combination therapy for initial and re-therapy for all genotypes

Sofosbuvir is the third DAA agent (referred to as a 'direct antiviral agent', 'direct-acting antiviral agent', 'direct antiviral substance' or 'directly acting antiviral drug') that intervenes in the replication of the virus, but the first polymerase -Inhibitor.

At the beginning of 2015, the DGVS published an addendum to its guideline from 2014, which recommends interferon-free combination therapy with sofosbuvir and ribavirin for initial therapy in genotype 2.

Ledipasvir from the group of NS5A inhibitors was approved in the EU in 2014 as a combination preparation with sofosbuvir ( Harvoni ® ).

An approved combination therapy from AbbVie ( Viekirax ® ) consists of ombitasvir, paritaprevir and ritonavir .

Former standard therapy

The standard treatment (as of 2009) consisted of a combined therapy with pegylated interferon α (peginterferon alfa-2a or peginterferon alfa-2b) and the antiviral ribavirin for a period of 24 to 48, rarely 72 weeks. Peg-interferon is given as an injection under the skin once a week, ribavirin is given daily in tablet form (sometimes also in liquid form for children).

The aim of the treatment is that six months after the end of therapy no virus can be detected (HCV-RNA negative). When this point is reached, patients are cured. Later relapses are very rare.

Depending on the genotype of the virus present in the patient, there is a 50 to 80% chance of permanently eliminating the virus with this therapy. With genotypes 2 and 3, the probability of success is significantly higher than with genotype 1. Other important factors for successful therapy are age, gender, viral load , duration of the disease, body weight and degree of liver damage. Additional illnesses such as HIV or hepatitis B infection can make the therapy more difficult.

In the meantime, the duration of the therapy is not only adjusted according to the genotype, but also according to how quickly or slowly the amount of virus drops in the first 4, 12 and possibly 24 weeks.

With hepatitis C treatment, numerous side effects are to be expected, which vary in severity depending on the patient. (Peg) -Interferon α can lead to flu-like symptoms (fever, chills), fatigue, slight hair loss, malfunction of the thyroid gland and psychological side effects such as depression , aggression or anxiety. If patients already have a history of depression, an antidepressant can be given in selected cases before interferon therapy is started. The most common side effect with ribavirin is a decrease in red blood cells ( hemolysis ); this can lead to the ribavirin dose being reduced and, in severe cases, the therapy being stopped prematurely. Since a sufficient amount of ribavirin is important for the chances of recovery, one tries to avoid dose reductions as much as possible.

The decision for or against therapy is made individually. Important for the decision are the course of the disease, any contraindications and the likely treatment opportunities, but also the life situation of the person concerned. Treatment should be carried out and monitored by a doctor experienced in therapy.

A new study showed that patients with acute hepatitis C can benefit if the start of therapy is delayed for a few weeks. A fifth of the patients were able to heal spontaneously, after which no further therapy was necessary.

New drugs

In addition to new interferons and ribavirin substitutes, research is also being carried out into means that directly prevent the virus from multiplying ( protease and polymerase inhibitors ). In 2011, the protease inhibitors telaprevir and boceprevir were approved in the USA, the EU and Japan. Both boceprevir and telaprevir must be combined with peg interferon and ribavirin. Both substances are only approved for genotype 1 of the hepatitis C virus. Protease and polymerase inhibitors, as individual substances, significantly reduce the viral load (to values below 600,000 IU / ml), but quickly create resistance, which increases the amount of virus again. Triple therapies with telaprevir or boceprevir are significantly more effective in genotype 1, but side effects and interactions with other drugs must be taken into account. Telaprevir and boceprevir can make the anemia worse. With telaprevir, rashes and itching in the anal area are seen more often. Taste disorders (dysgeusia) may occur more often with boceprevir.

In addition to antiviral substances in combination with peg interferon and ribavirin, research is also being carried out into interferon-free therapies against hepatitis C. In April 2011, at the EASL Liver Congress, interferon-free cures under controlled conditions were reported for the first time: 4 of 11 hepatitis C patients with genotype 1 became cured by interferon-free treatment with asunaprevir and daclatasvir. Daclatasvir and others are particularly convincing due to the relatively short therapy required, as the viral load is reduced from the first day. Further interferon-free combination therapies are being researched. A 12-week combination therapy of GS-7977 (PSI-7977) with ribavirin was able to cure 10 of 10 hepatitis C patients with genotypes 2 and 3, but this double combination was sufficient for previously unsuccessfully pretreated HCV genotype 1 patients (“zero -Responder "without Rapid Virological Response and without Early Virological Response ) is not effective for healing.

A combination of sofosbuvir and velpatasvir ( Epclusa ® ) has shown a cure rate of 99% in a study.

prevention

No vaccine for active immunization against hepatitis C is approved. Existing protective measures have been limited to preventing exposure by avoiding blood-to-blood contact with infected people, for example, when taking intravenous drugs, everyone only uses their own syringe and needle. To reduce the temptation to share syringes, drug counseling centers offer injection sets free of charge. Infected people should learn to be careful with blood ( AIDS help ). This mainly includes becoming aware of possible blood contact and avoiding sharing nail scissors, razors and toothbrushes with non-infected people. A condom should also be used during sexual intercourse.

There is no post- exposure prophylaxis after infection with hepatitis C, as is known in hepatitis B or HIV. If hepatitis C is discovered and treated in the first six months after infection, a 24-week interferon therapy can lead to a cure in more than 90% of cases before the disease becomes chronic.

Transmission of hepatitis C viruses through medical measures

Transmission as part of schistosomiasis treatment

During the 1950s to the 1980s, the Egyptian health authorities were fighting together with the World Health Organization that there very common schistosomiasis with organized campaigns where the sick tartar emetic ( tartar emetic ) was injected. The hepatitis C virus was probably infected through cannulas that were not adequately disinfected. In later serological examinations the virus antigens could be detected in 70–90% of all cases of chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis and liver cell carcinoma. The number of people affected is estimated at six million. Since the above-mentioned complications of a hepatitis C virus infection often only appeared after twenty years, infectiologists believe that the climax of the epidemic of liver diseases in Egypt is still ahead. It is probably the most serious case of medical ( iatrogenic ) transmitted pathogens in history.

Transmission as part of anti-D immune prophylaxis

The anti-D immune prophylaxis is intended to prevent a rejection reaction against a rhesus positive fetus in a mother who lacks Rh factor D (rhesus negative) in a second pregnancy. At birth, the child's blood always enters the mother's bloodstream. If the woman is rhesus negative and her child is rhesus positive, the woman can develop antibodies against the rhesus factor, which is foreign to her. In another pregnancy with a rhesus-positive fetus, the maternal antibodies can then cross the placenta and lead to disabilities in the fetus and even death. To avoid this, anti-D immunoglobulins are injected immediately after the birth of the first and subsequent children, thus protecting subsequent siblings.

Germany

In the GDR , anti-D immune prophylaxis was required by law. In 1978 and 1979, several thousand women were given immunoglobulins contaminated with hepatitis C viruses - in press reports there were 6,700. The manufacturer (BIBT Halle) and patent holder of the GDR anti-D immunoprophylaxis was already aware of the hepatitis C virus contamination of the starting material (blood plasma) in 1978 before the relevant serum batches were produced. The donors of the blood plasma (raw material for the production of anti-D immunoprophylaxis) were in inpatient treatment for acute non-A-non-B hepatitis (hepatitis C virus), and it was therefore already clear before the anti-D serum was produced that the Blood plasma donated by the inpatients had to be non-A-non-B (hepatitis C) virus contaminated. It was therefore not just a drug scandal , but the largest drug crime in the GDR, as documented in the files of the non-public main hearing of the 4th criminal division of the Halle / Saale district court (file number 4 BS 13/79 of November 27, 1979) . The virus-contaminated batches had been released by the District Institute for Blood Donation and Transfusion of the Halle District (BIBT) and the State Control Institute for Serums and Vaccines (source: investigation files for file number 4 BS 13/79). The anti-D drug crime victims were initially supported in accordance with the GDR law for the prevention and control of communicable diseases in humans (GüK). The federal government in reunified Germany then argued that the compensation was a state matter. The women affected were considered to have been vaccinated and therefore received benefits under the Federal Disease Act . On June 9, 2000, the Bundestag passed the Anti-D-Aid Law , according to which infected women, their infected children born after immunoprophylaxis and other infected contact persons are entitled to medical treatment and financial help. The pension benefits are between 271 and 1082 euros per month (status: 2004); 2464 applications were accepted. The peak of the one-off payments was reached in 2000 with seven million euros; In addition, around two million euros are paid annually in pensions, at least half of which is financed by the federal government. In 2001 the Federal Audit Office examined the implementation of the law and criticized the inconsistent handling of applications in the federal states; he suggested stricter federal supervision. In terms of the number of people affected, it is - after the Contergan scandal - the largest pharmaceutical scandal in German post-war history.

For those infected with HIV in the so-called blood scandal in the 1990s, 90 percent of the cases were co-infected by blood products contaminated with the hepatitis C virus. This blood scandal also affected around 1200 other haemophilic patients who were not co-infected with the HI virus. Like HIV infection, these infections could have been prevented with appropriate virus inactivation of the coagulation preparations. To date (as of summer 2019) there has been no compensation for this hepatitis C blood scandal.

Ireland

In Ireland, blood donations have been tested for antibodies against the hepatitis C virus since October 1991. A regional study found that 13 out of 15 infected women were rhesus negative (three would have been expected); at the same time they were considerably older than the average donor. Twelve of these women had received anti-D immunoprophylaxis in 1977. This discovery sparked a crisis of confidence in the Irish Blood Transfusion Service Board . In 1996 a national commission of inquiry was set up. Over 62,000 women who received immunoprophylaxis between 1970 and 1994 were tested and found that batches of anti-D immunoglobulins used in 1977 and 1978 had been contaminated with hepatitis C virus. The commission found that the blood plasma of a single contaminated person had caused the contamination. In 1997 a tribunal was set up to decide on compensation claims. Of 1,871 applications, 1,042 (as of November 1998) were recognized as eligible and compensation was paid totaling $ 219 million. That equates to an average compensation of $ 210,173 per case.

155 women were followed up 22 years after the initial infection. The most common symptoms reported were fatigue and joint pain; 77 percent of the women also had clinically meaningful anxiety symptoms. The hepatitis C infection could only be detected with PCR in 87 women ; the others seemed to have eliminated the virus spontaneously; however, almost half of these still showed antibodies. Strikingly, every fifth woman in this group had hepatitis. A liver biopsy was also performed in 27 (40%) of the PCR-negative patients; this revealed minimal inflammatory changes such as mild inflammation and minimal fibrosis. Four (14.8%) people had normal liver histological findings, 20 (74%) people had mild inflammation, and three (11.1%) people had moderate to severe liver disease. Only 3.4 percent of women with detectable viruses had hepatitis. The viral load does not seem to reflect the severity of the clinical symptoms. In no single case could cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma be detected. Overall, this study showed that in a surprisingly high proportion of women, their bodies had eliminated the virus and that the disease did not tend to get worse over the years. Despite the favorable course of the disease seen here, there were strong psychological symptoms of stress and a poor quality of life.

Transmission through blood coagulants

In Japan, since October 2002, around 240 people have sued the state for infection with hepatitis C viruses from blood coagulants, specifically fibrinogen . Most of the sick had received the blood products during childbirth. In January 2008, the government ended the legal proceedings with a settlement: On this basis, the Japanese parliament passed a law on January 15 that awarded the victims compensation between 12 and 40 million yen (about 75,000 to 250,000 euros). About 1,000 people were initially designated as eligible. Prime Minister Yasuo Fukuda apologized to those affected and took responsibility on behalf of the state. The compensation fund will be equipped with 20 billion yen, into which the manufacturers of the contaminated blood products will also pay. On February 15, 2008, the Ministry of Health revealed that the actual number of people infected is believed to be 8,896. So far, only around 40 percent of those affected have been informed. As manufacturers of the contaminated blood products, three companies, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corp. as well as its subsidiary Benesis Corp. and Nihon Pharmaceutical Co. named. At Mitsubishi Tanabe is the successor of Green Cross Corp. which the fibrinogen originally produced. Green Cross became famous in Japan because scores of people developed AIDS after selling blood products contaminated with HIV .

The highest risk of infection with hepatitis C was in recipients of blood products obtained from several thousand individual donations, such as: B. Haemophiles . The clarification of the exact circumstances of the so-called " blood scandal", in which primarily the infection by blood products contaminated with HIV was discussed, continues to this day.

Transmission through contaminated syringes

According to a study by the University of Valencia, anesthesiologist Juan Maeso Vélez infected at least 171 patients with hepatitis C between 1994 and 1998 in two hospitals in Valencia. The study, with which it was possible to arrest Maeso as the only source, was carried out as part of a court case in 2000.

According to press reports, several people in a clinic in Las Vegas became infected with hepatitis viruses or HIV through unclean syringes . Since March 2004 the employees at the "Endoscopy Center of Southern Nevada" are said to have used disposable syringes and injection vials several times according to the clinic director's instructions, so that the viruses could be transmitted in this way. The scandal came to light when six hepatitis C cases were reported to the responsible district in February 2008.

Cost aspects

A twelve-week therapy with the most effective tablets Sofosbuvir costs around 41,000 euros in Germany from January 23, 2015. The manufacturer Gilead reported global Sofosbuvir sales of $ 5.7 billion in the first half of 2014 . Egypt, where up to 22% of the population is infected with HCV, agreed with Gilead to give 150,000 critical-stage patients sofosbuvir for $ 300 instead of the $ 84,000 they could never pay. The high costs of the latest generation of drugs are controversial and lead to restrictions on the part of insurance companies when it comes to assuming the costs. The costs of previous therapy options, e.g. B. with interferon + ribavirin + telaprevir are about 90,000 €, the therapy lasts up to 48 weeks.

Reporting requirement

In Germany, all acute viral hepatitis (including acute hepatitis C) must be reported by name in accordance with Section 6 of the Infection Protection Act (IfSG) . This concerns the suspicion of an illness, the illness as well as death from this infectious disease. In addition, any evidence of the hepatitis C virus must be reported by name in accordance with Section 7 IfSG.

In Austria, after § 1 1 para. Epidemics Act 1950 of suspicion, illness and deaths from infectious hepatitis (hepatitis A, B, C, D, E) , including hepatitis C, notifiable .

Also in Switzerland is subject to hepatitis C the reporting requirement and that after the Epidemics Act (EpG) in connection with the epidemic Regulation and Annex 1 of the Regulation of EDI on the reporting of observations of communicable diseases of man . Reporting criteria for this message by doctors, hospitals, etc. are a positive laboratory analytical finding and the request by the cantonal doctor or the cantonal medical report, the case. Laboratories must report positive laboratory results for the hepatitis C virus in accordance with Appendix 3 of the above-mentioned EDI ordinance.

literature

- H. Wedemeyer, M. Cornberg, MP Manns: PEG interferons: importance for the therapy of viral hepatitis B and C. In: Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2001 Jun 1; 126 Suppl 1, pp. S68-S75, PMID 11450618

- E. Herrmann, C. Sarrazin: Hepatitis C Virus - Virus Kinetics and Resistance Mechanisms. In: Z Gastroenterol. 1998; 36, pp. 997-1008, PMID 15136939

- J. Hadem, H. Wedemeyer, MP Manns: Hepatitis as a motion sickness. In: Internist. 2004; 45, pp. 655-668, PMID 15118829

- Gert Frösner: Modern hepatitis diagnostics. ISBN 3-932091-50-7 .

- Stefan Zeuzem: Hepatitis C in dialogue - 100 questions - 100 answers. ISBN 3-13-133391-X .

- The German Hepatitis C Handbook . Editor: German Hepatitis C Forum e. V., ISBN 3-00-004025-0 .

- WP Hofmann: Treatment of patients with chronic hepatitis C: Current HCV therapy standard . In: Dtsch Arztebl Int . No. 109 (19) , 2012, pp. 352-358 ( review ).

- Gerhard Scheu : Product responsibility for hepatitis C infections in haemophilic patients. Nomos, Baden-Baden 1999, ISBN 3-7890-6385-1 (The author was the chairman of the committee of inquiry of the 12th German Bundestag on this subject.)

- Hartwig Klinker: Virus infections. In: Marianne Abele-Horn (Ed.): Antimicrobial Therapy. Decision support for the treatment and prophylaxis of infectious diseases. With the collaboration of Werner Heinz, Hartwig Klinker, Johann Schurz and August Stich, 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Peter Wiehl, Marburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-927219-14-4 , pp. 297–307, here: pp. 299–301.

Web links

- Hepatitis C - information from the Robert Koch Institute

- Competence network hepatitis

- Laboratory Lexicon: Hepatitis C

- National Hepatitis C Program US Department of Veterans Affairs (in English)

- S3 guideline : Diagnosis and therapy of the hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection , AWMF register number 021/012, full text (PDF) as of 2018

- S3 guideline prophylaxis, diagnosis and treatment of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, AWMF register no .::021/012

Individual evidence

- ^ QL Choo, G. Kuo et al. a .: Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from a blood-borne non-A, non-B viral hepatitis genome. In: Science . Volume 244, Number 4902, April 1989, pp. 359-362, PMID 2523562 .

- ↑ Donald B. Smith, Jens Bukh, Carla Kuiken, A. Scott Muerhoff, Charles M. Rice: Expanded classification of hepatitis C virus into 7 genotypes and 67 subtypes: updated criteria and genotype assignment web resource . In: Hepatology . tape 59 , no. 1 , 2014, ISSN 1527-3350 , p. 318–327 , doi : 10.1002 / hep.26744 , PMID 24115039 , PMC 4063340 (free full text).

- ↑ Jan Felix Drexler , Victor Max Corman, Marcel Alexander Müller a. a .: Evidence for Novel Hepaciviruses in Rodents. In: PLoS Pathogens . 9, No. 6, 2013 doi: 10.1371 / journal.ppat.1003438

- ↑ S. Fujioka, H. Shimomura et al. a .: Prevalence of hepatitis B and C virus markers in outpatients of Mongolian general hospitals. In: Kansensh? Gaku zasshi. The Journal of the Japanese Association for Infectious Diseases. Volume 72, Number 1, January 1998, pp. 5-11, PMID 9503777 .

- ^ Robert Koch Institute: Epidemiological Bulletin . 13/2006.

- ^ Robert Koch Institute: Epidemiological Bulletin. 46/2005.

- ↑ G. Seger: Drugs and hepatitis C: New concepts of prevention sought. In: Dtsch Arztebl. Volume 101, Number 27, 2004.

- ↑ GL Armstrong, A. Wasley et al. a .: The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1999 through 2002. In: Annals of Internal Medicine . Volume 144, Number 10, May 2006, pp. 705-714, PMID 16702586 .

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 3 of the RKI (PDF) January 18, 2002.

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 3 of the RKI (PDF) January 17, 2003.

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 2 of the RKI (PDF) January 16, 2004.

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 2 of the RKI (PDF) January 14, 2005.

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 3 of the RKI (PDF) January 20, 2006.

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 3 of the RKI (PDF) January 19, 2007.

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 3 of the RKI (PDF) January 18, 2008.

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 3 of the RKI (PDF) January 19, 2009.

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 3 of the RKI (PDF) January 25, 2010.

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 3 of the RKI (PDF) January 24, 2011.

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 3 of the RKI (PDF) January 23, 2012.

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 3 of the RKI (PDF) January 21, 2013.

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 3 of the RKI (PDF) January 20, 2014.

- ↑ Bulletin No. 3 of the RKI (PDF) January 14, 2015.

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 3 of the RKI (PDF) January 20, 2016.

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 3 of the RKI (PDF) January 18, 2017.

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 3 of the RKI (PDF) January 17, 2018.

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 3 of the RKI (PDF) January 17, 2018.

- ↑ a b Epidemiological Bulletin No. 3 of the RKI (PDF) January 16, 2020

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Hepatitis C FAQs for Health Professionals

- ↑ Guideline ( Memento of the original from January 12, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 1 MB)

- ↑ Hartwig Klinker: Hepatitis C. In: Marianne Abele-Horn (Ed.): Antimicrobial Therapy. Decision support for the treatment and prophylaxis of infectious diseases. With the collaboration of Werner Heinz, Hartwig Klinker, Johann Schurz and August Stich, 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Peter Wiehl, Marburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-927219-14-4 , pp. 299–301, here: p. 299 (in studies such as HepNet).

- ↑ a b dgvs.de (PDF)

- ↑ Ira M. Jacobson, Stuart C. Gordon, Kris V. Kowdley, Eric M. Yoshida, Maribel Rodriguez-Torres, Mark S. Sulkowski, Mitchell L. Shiffman, Eric Lawitz, Gregory Everson, Michael Bennett, Eugene Schiff, M. Tarek Al-Assi, G. Mani Subramanian, D. i. An, Ming Lin, John McNally, Diana Brainard, William T. Symonds, John G. McHutchison, Keyur Patel, Jordan Feld, Stephen Pianko, David R. Nelson: Sofosbuvir for Hepatitis C Genotype 2 or 3 in Patients without Treatment Options. In: New England Journal of Medicine. 2013, p. 130423030016000, doi: 10.1056 / NEJMoa1214854 .

- ↑ Eric Lawitz, Alessandra Mangia, David Wyles, Maribel Rodriguez-Torres, Tarek Hassanein, Stuart C. Gordon, Michael Schultz, Mitchell N. Davis, Zeid Kayali, K. Rajender Reddy, Ira M. Jacobson, Kris V. Kowdley, Lisa Nyberg, G. Mani Subramanian, Robert H. Hyland, Sarah Arterburn, Deyuan Jiang, John McNally, Diana Brainard, William T. Symonds, John G. McHutchison, Aasim M. Sheikh, Zobair Younossi, Edward J. Gane: Sofosbuvir for Previously Untreated Chronic Hepatitis C Infection. In: New England Journal of Medicine. 2013, p. 130423030016000, doi: 10.1056 / NEJMoa1214853 .

- ↑ C. Neumann-Haefelin, HE Blum, R. Thimme: Direct antiviral therapeutic approaches in chronic hepatitis C In: Dtsch med Wochenschr. 2012; 137 (25/26), pp. 1360-1365. doi: 10.1055 / s-0032-1305064 .

- ↑ Christoph Sarrazin, Thomas Berg, Peter Buggisch, Matthias Dollinger, Holger Hinrichsen, Dietrich Hüppe, Michael Manns, Stefan Mauss, Jörg Petersen, Karl-Georg Simon, Heiner Wedemeyer, Stefan Zeuzem: Current recommendation of the DGVS and the bng for the therapy of chronic Hepatitis C ( Memento of the original from April 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , DGVS guideline; last accessed on March 8, 2015.

- ↑ European Commission grants approval for Harvoni. Retrieved March 21, 2015 .

- ↑ TECHNIVIE ™ (ombitasvir, paritaprevir and ritonavir) tablets, for oral use. Full prescribing information . AbbVie Inc., North Chicago, IL 60064. Retrieved July 28, 2015.

- ↑ Katja Deterding, Norbert Grüner, Peter Buggisch, Johannes Wiegand, Peter R. Galle, Ulrich Spengler, Holger Hinrichsen, Thomas Berg, Andrej Potthoff, Nisar Malek, Anika Großhennig, Armin Koch, Helmut Diepolder, Stefan Lüth, Sandra Feyerabend, Maria Christina Jung, Magdalena Rogalska-Taranta, Verena Schlaphoff, Markus Cornberg, Michael P. Manns, Heiner Wedemeyer: Delayed versus immediate treatment for patients with acute hepatitis C: a randomized controlled non-inferiority trial. In: The Lancet Infectious Diseases . 13, 2013, pp. 497-506, doi: 10.1016 / S1473-3099 (13) 70059-8 .

- ↑ FDA approves telaprevir, May 13, 2011 , report on Medscape.com, accessed February 26, 2019

- ↑ Victrelis (Boceprevir) Approval history on drug.com, accessed February 26, 2019

- ↑ Hartwig Klinker: Infections by hepatitis viruses. In: Marianne Abele-Horn (Ed.): Antimicrobial Therapy. Decision support for the treatment and prophylaxis of infectious diseases. With the collaboration of Werner Heinz, Hartwig Klinker, Johann Schurz and August Stich, 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Peter Wiehl, Marburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-927219-14-4 , pp. 299–301, here: pp. 300 f.

- ↑ Product information of the European Medicines Agency on telaprevir

- ↑ Product information on boceprevir from the European Medicines Agency

- ↑ New HCV Drugs at AASLD. Natap.org

- ↑ Anna S. Lok u. a .: Preliminary Study of Two Antiviral Agents for Hepatitis C Genotype 1. In: N Engl J Med , 2012, 366, pp. 216-224.

- ↑ J. Guedja, H. Daharia, L. Rong, ND Sansonee, RE Nettlesh, SJ Cotlere, TJ Laydene, SL Uprichardd, AS Perelson: Modeling shows that the NS5A inhibitor daclatasvir has two modes of action and yields a shorter estimate of the hepatitis C virus half-life. doi: 10.1073 / pnas.1203110110

- ↑ Are we ready for IFN-free treatment regimens? Natap.org

- ↑ Conference Reports for NATAP , accessed March 26, 2014.

- ↑ Hartwig Klinker (2009), p. 300.

- ↑ Hepatitis C: Setback for GS-7977 for null correspondents with genotype 1 . ( Memento of the original from March 1, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. German Liver Aid e. V.

- ↑ Ellen Reifferscheid: New introduction to Epclusa. In: Yellow List. Medical Media Informations GmbH, August 4, 2016, accessed on July 21, 2017 .

- ↑ Jordan J. Feld, Ira M. Jacobson, Christophe Hézode, Tarik Asselah, Peter J. Ruane, Norbert Gruener, Armand Abergel, Alessandra Mangia, Ching-Lung Lai, Henry LY Chan, Francesco Mazzotta, Christophe Moreno, Eric Yoshida, Stephen D. Shafran, William J. Towner: Sofosbuvir and Velpatasvir for HCV Genotype 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 Infection . In: New England Journal of Medicine . November 16, 2015, p. 151117120417004. doi : 10.1056 / NEJMoa1512610 .

- ↑ GT Strickland: Liver disease in Egypt: hepatitis C superseded schistosomiasis as a result of iatrogenic and biological factors. In: Hepatology . Volume 43, No. 5, 2006, pp. 915-922.

- ↑ C. Frank et al. a .: The role of parenteral antischistosomal therapy in the spread of hepatitis C virus in Egypt. In: The Lancet . Volume 355, No. 9207, 2000, pp. 887-891.

- ↑ Compensation for people infected with hepatitis C. In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt. Volume 94, No. 9, 1997, pp. A-500 / B-422 / C-398. ( aerzteblatt.de )

- ↑ Major question from the MPs Horst Schmidbauer u. a. on infection by plasma contaminated with hepatitis C in 1978/1979 in the GDR dipbt.bundestag.de German Bundestag, printed matter 13/1649 of June 7, 1995.

- ↑ German Bundestag, (PDF) Printed matter 15/2792 (PDF)

- ^ Aids scandal: hemophiliacs demand compensation. In: Hamburger Abendblatt . August 17, 1999, accessed April 1, 2019 .

- ↑ Elizabeth Kenny-Walsh: Clinical Outcomes after Hepatitis C Infection from Contaminated Anti-D Immune Globulin. In: The New England Journal of Medicine. Volume 340, No. 16, 1999, pp. 1228-1233.

- ↑ S. Barrett et al. a .: The natural course of hepatitis C virus infection after 22 years in a unique homogenous cohort: spontaneous viral clearance and chronic HCV infection. In: Good. Volume 49, 2001, pp. 423-430.

- ↑ Hepatitis C victims settle lawsuits filed against state. In: The Japan Times. February 5, 2008. ( search.japantimes.co.jp )

- ↑ Hepatitis C bill offering aid, apology clears Diet. In: The Japan Times. January 12, 2008. ( search.japantimes.co.jp )

- ↑ Report increases hepatitis C exposure cases to 8,896. In: The Japan Times. February 16, 2008. ( search.japantimes.co.jp )

- ^ Blood scandal: Miracles of Bonn . In: Der Spiegel . No. 41 , 1994 ( online ).

- ↑ Application for a compensation scheme for hemophiliacs infected with HCV through blood products. German Bundestag, January 21, 2009; dip21.bundestag.de (PDF)

- ↑ Udo Ludwig: death on prescription . In: Der Spiegel . No. 32 , 2009 ( online ).

- ↑ El ADN revela que el anestesista Maeso Contagio la hepatitis C a 171 pacientes. In: El País. February 24, 2000. ( elpais.com )

- ↑ Clinical staff used contaminated syringes on 40,000 patients - as directed . In: Spiegel Online , February 29, 2008.

- ↑ Volker Stollorz: Cure jaundice, pay well . on: faz.net , July 28, 2014.

- ^ Rita Flubacher: A pack of pills for 19,000 francs. In: Tages-Anzeiger, August 7, 2014, p. 1.