cold

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| J00-J06 | Acute upper respiratory infections |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

Colds ( also known as colds in Austria ) and flu or viral infections are everyday, medically not clearly defined terms for an acute infectious disease of the mucous membrane of the nose (including the sinuses ), the throat and / or the bronchi . The infectious disease is mainly caused by very different viruses , sometimes also by bacteria ( secondary infection , also called superinfection in this context ). The most common cold viruses are among the viral species of rhinoviruses , enteroviruses and Mastadenoviruses or the families of Corona - and Paramyxoviridae .

Colds are very common in children and infants, with the incidence decreasing with age. If an infant falls ill about 6 to 8 times a year, it occurs 3 to 5 times in nine-year-olds and 1 to 2 times in adults. The frequency can also increase due to a particular exposure (siblings, kindergarten, etc.). Colds (respiratory infections) are among the most common infectious diseases in humans.

The flu-like infection should not be confused with the “real” flu ( influenza ), which is much more severe in around a third of those infected and is particularly common for people with a weak immune system , e.g. B. Infants and the elderly , can be fatal.

Possible links between cold and colds

The traditional and still widespread assumption that colds are regularly caused by cold alone - in the scientific sense of heat extraction as a pathophysiological mechanism - or that it causes or forms of cold, such as drafts , moisture, hypothermia , is incorrect. Cold alone cannot cause a cold, so the cold factor is not a sufficient condition . Since you can catch a cold without having been exposed to the cold, cold is also not a necessary condition . Any other connection with cold suggested by the word “common cold” has been controversial so far.

The first symptom of a cold is often the subjective feeling of being cold. The immune system reacts to a previous viral infection by releasing messenger substances that cause the thermoregulation in the hypothalamus to increase body temperature . The attempt by the body to bring the core temperature to the target temperature includes reduced blood flow and cooling of the skin and extremities, build-up of body hair ( goose bumps ), increase in muscle tone to the point of muscle tremors. The feeling of coldness at the onset of the illness is therefore a consequence of the virus infection and not its immediate cause.

The remaining assumption that colds are favored by cold has not been confirmed or disproved unequivocally by researchers since the 1960s. Since science is also influenced by the phenomena of the times, there was a tendency in the subsequent period to doubt this connection. In the USA, names other than the term common cold , which is primarily used by authorities, are therefore often used, e.g. B. [viral] upper respiratory [tract] infection (URI), acute viral nasopharyngitis , and acute coryza , to tone down the idea of the association between cold and infection. However, the cold can indirectly increase the risk of infection, as people spend more time in buildings, in poorly ventilated rooms and therefore in the vicinity of infected people when the weather is cold. It is unclear whether wet-cold climate affects the risk of infection in other ways, for example by changes in the immune system, the number of ICAM-1 - receptors (specific receptors for cell adhesion molecule ICAM-1, a key protein for the leukocyte - endothelial -Interaction in the body) or even just the amount of nasal secretions and hand contact with the face. Cold has an inhibitory effect on the respiratory ciliated epithelium (mucociliary apparatus) and thus inhibits its ability to clean, which, together with a narrowing of the small bronchi , can promote infections. Furthermore, the air indoors is drier in winter than in summer, which is why people's mucous membranes are drier and more susceptible to infections in winter due to the lower relative humidity of the air we breathe. In addition, the large group of human rhinoviruses, which are responsible for 40 percent of the common cold, have a “preference” for cold and wet climates.

Newer, obtained in studies findings confirm the relationship between cold and flu so far, as well as an excessively long or intense exposure to cold on a inadequately protected body to a weakening of the immune system and thereby lead to poor defense against the pathogens can .

A 2005 study by Cardiff University showed a possible link between exposure to the cold and cold symptoms. While 13 out of 90 study participants who had to take a cold foot bath reported cold symptoms, only 5 out of 90 in the control group, who merely kept their feet in an empty bowl. The total of 18 participants who reported cold symptoms continued to suffer own information from more colds per year than those 162 participants who reported no cold symptoms after the attempt. It is believed that the cold leads to a deterioration in blood circulation and thus hinders the transport of white blood cells to the focus of infection (the pathogen's entry point). In addition, allergies , bacterial infections of the respiratory tract and weather changes can trigger symptoms similar to colds and lasting for days. According to this, the climate factor cold would only be an accompanying influencing factor (cofactor) that can promote the onset of the disease after a virus infection. This also applies to tropical temperatures, at which the action of drafts on an overheated or damp body can lead to a strong cooling of the body surface. Care should therefore be taken not to expose the body to the direct flow of air from a fan or air conditioning system, e.g. B. when sleeping.

Newer theories assume that a lack of vitamin D leads to a weakening of the immune system. Vitamin D is formed in the skin through sunlight; in winter, solar radiation is particularly low due to the short duration of daylight and a vitamin D deficiency is therefore particularly likely. This could increase the susceptibility to disease in winter. There would then be a correlation between cold and colds, but not causality . Rather, winter cold and immune-weakening vitamin D deficiency would then be consequences of a third cause, namely the short duration of sun exposure on winter days.

In a 2015 study, scientists working with Akiko Iwasaki from the Yale University School of Medicine were able to use mucous membrane cell cultures in the airways of mice to show that rhinoviruses multiply faster at cool temperatures and that the immune system of the epithelial cells is weakened.

Pathogens

More than 200 very different viruses from different virus families have been described as causing the disease. They are all adapted to the epithelia of the easily accessible airways and cause similar symptoms. Since the airways from the pharynx to the branches of the bronchial tree have several barriers of defense cells, the pathogens have to bypass the immune defense by a particularly rapid increase ( replication ) and by means of many different variants. The symptoms of the common cold it causes, such as coughing , increased mucus production and sneezing , in turn, enable the viruses to get to a new host very easily . The pathogens are in detail:

- from the Picornaviridae family, for example, the human rhinovirus -1A (HRV-1A) or 1B with more than 100 subtypes, the coxsackieviruses B1 (CVB-1) to B6, various echoviruses and human enteroviruses (around 40 subtypes).

- These viruses belong to the group of non-enveloped single (+) stranded RNA viruses [ss (+) RNA].

- from the family of the Coronaviridae the human coronavirus 229E (HCoV-229E), the human coronavirus OC43 (HCoV-OC43), the human coronavirus NL63 (HCoV-NL63) and the human coronavirus HKU1 (HCoV-HKU1).

- These viruses belong to the enveloped single (+) stranded RNA viruses [ss (+) RNA]. Coronaviruses cause up to 30 percent of seasonal colds in Germany.

- from the family Paramyxoviridae the human parainfluenza viruses 1-4, the human metapneumovirus (HMPV) and the human respiratory syncytial virus (HRSV) type A and B (all enveloped ss (-) RNA viruses).

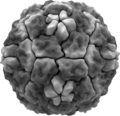

- from the family of Adenoviridae , gender Mastadenovirus various serotypes of species Human adenoviruses A-F .

- These viruses belong to the class of non-enveloped double-stranded DNA viruses (dsDNA).

- individual species from the Reoviridae family (dsRNA, unenveloped).

The frequency of these pathogens in colds is approximately 40% rhinoviruses, 10-15% RSV and up to 30% coronaviruses. The human metapneumovirus (HMPV) is now the second most common cold pathogen in young children. The other pathogens are generally rarely found outside of local outbreaks. The enveloped viruses can achieve a variability and thus a bypassing of the immune defense by changing the surface proteins of the virus envelope . This is particularly the case with the very variable enveloped RNA viruses , which have constant spontaneous variances within a few virus species due to the higher mutation rate in RNA replication compared to DNA replication and are also subject to constant changes between the usual cold months. Non-enveloped viruses are dependent on a large number of subtypes due to the necessary stability and therefore lower variance of their capsid , the genomes of which, however, are inherently very stable.

"Summer flu"

In the summer months, cold symptoms are often caused by various enteroviruses , including a. the Coxsackie , ECHO and Parechoviruses . Respiratory (breathable) adenoviruses and human parainfluenza virus 3 also occur in summer, and human parainfluenza virus 4 in early summer . The phenomenon of cold symptoms in the summer months is also known colloquially as summer flu , although real flu viruses ( influenza viruses ) are not involved.

Colds in winter

During this time of year, the most important causative agents of colds in children are RSV, human rhinoviruses and adenoviruses. In adults, the RSV is of less importance.

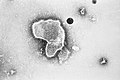

Coronavirus virion

The multitude of different viruses and their subtypes explains why people can catch a virus-related cold so often. The fact that a flu-like infection does not take a fatal course in people who are not significantly pre-damaged and if there is no double infection or secondary infection (see also: Infection ) shows, on the one hand, that the viruses identified as causative agents for this disease very strongly affect people as theirs Reservoir host are adapted. Damage to its reservoir host is not an advantageous effect for a virus, since it depends on it to reproduce itself. The symptoms that are nevertheless triggered in the reservoir host are side effects of the infection. On the other hand, it also makes it clear that humans have also been able to adapt to these viruses over the course of many generations. In this regard, there is a clear difference to the influenza viruses and the diseases they cause in humans.

distribution

The viruses that cause a cold, with their innumerable species and their mutations , can occur in all climatic zones worldwide and spread through infection wherever people are to be found.

transmission

The disease-causing viruses are transmitted both as droplet infections through the air and directly or indirectly through contact with sick people or through contaminated objects by smear infection (contact infection) in their surroundings. The practical relevance of these different routes of infection cannot currently be conclusively assessed despite the extensive scientific literature. To this day, the importance of possibly beneficial factors such as virus type, climatic conditions and hygiene habits such as blowing one's nose, washing hands and using towels is still controversial , while there is broad agreement that the majority of "cold viruses" are not very contagious, so that an infection is usually longer and narrower Contact requires. On the other hand, the serotypes of the virus types human adenovirus A – F causing a common cold have been shown to be contagious for a long time outside the host body.

Role of the immune system

Especially in the case of infections with pathogens that are already adapted to humans as their reservoir host, as is the case with the cold viruses, the condition of the immune system of the organism concerned plays an important role. Whether an illness actually occurs after such an infection depends on the amount and virulence of the pathogen and the state of the immune system of the person concerned. The observation that not all contact persons get sick with colds has various causes. For example, previous contact with the virus variant in circulation may already result in immunity , the dose or virulence of the virus may be too low for an outbreak of disease or the immune system may be able to prevent symptoms of the disease despite infection (inapparent infection or silent celebration (immunization without vaccination or disease )). If the immune system is intact and the dose of pathogen is low, the common cold may either not break out at all or be less severe.

In this respect, factors that weaken the function of the human immune system as a whole can definitely influence the course of a cold. These include chronic diseases, drug immunosuppressive (the immune system suppressing) treatment such as after organ transplants , drug abuse (including nicotine and alcohol ), malnutrition , an unhealthy diet, environmental toxins , chronic stress, too little sleep, lack of exercise, overtraining or overwork, Irritation or weakening of the mucous membranes from dry air or dust generation. According to more recent findings, it may also be an excessive exposure to cold in the sense of prolonged cooling or even hypothermia ( hypothermia ) as well as a vitamin D deficiency due to low exposure to sunlight. A combination of several factors can put an increased burden on the immune system.

A particularly well-studied disease trigger is acute stress . Many cold symptoms appear two to three days after emotionally stressful events, the time lag being explained by the fact that the outbreak of a cold is preceded by a corresponding incubation period .

Course of disease

Usually a cold is harmless after an incubation period of around two to eight days. Half of all cases are over after 10 days, 90% after 15 days. Many people have several colds a year; four to nine illnesses per year are still considered normal for small children. Depending on the type of pathogen, an infected person can shed them from around twelve hours after the infection and around until the symptoms of the disease have subsided, or longer if treated with steroids ( cortisone ).

Symptoms

In the normal course

Depending on the spread of the pathogen in the body of the person concerned, starting from the place of the first fixation , the symptoms of a cold usually run in phases. The first signs are usually a sore throat up to sore throat and difficulty swallowing, which, unlike angina throat pain, only last up to two days, often combined with a slight chill. As particularly typical cold symptom often occurs at the same time an inflammation of the nasal membranes, which also rhinitis ( rhinitis is called), mainly announced by a burning and tickling in the nose and usually achieved with sneezing and head pressure peaked on the second Erkrankungstag . Almost always occur for a period of four to five days, head and body aches accompanying on. Some of the sick people feel dull and exhausted or even develop a fever , the level of which depends on the type of virus and the physical and mental state of the sick person. From around the sixth day of the illness, a dry, tickly cough can develop, which in the further course sometimes turns into a stubborn cough.

In most cases, the disease is over after about a week, but it can last up to two weeks.

Complications

If the cold viruses spread from the nasal mucosa to the throat, throat, bronchi, frontal and sinus cavities and into the ear canal, possible complications of the cold are, for example, sinuses - inflammation ( sinusitis ), otitis media , tonsillitis ( angina tonsillaris ), Inflammation of the throat ( pharyngitis ), inflammation of the airways / bronchial tubes ( tracheobronchitis ) and pneumonia (pneumonia) occur.

When an inflammation of the larynx ( laryngitis ) and the vocal folds (especially: vocal cords = vocal ligament sinistrum et dextrum ) the vibration behavior of the latter can often change in such a way that there is for a certain time to a deeper voice or even to voice loss.

Further complications can arise from the fact that every virus infection can temporarily weaken the immune system. As a result, bacteria belonging to the so-called local flora and normally not causing an infection ( commensals - in this case mainly streptococci ) can become pathogenic and then cause pneumonia, for example.

Cold and pregnancy

Especially during pregnancy, expectant mothers can catch a cold more easily, as the immune system does not always work reliably within this period of time. Symptoms such as headache and body aches in the pregnant woman, however, usually do not harm the health of the future child.

With regard to the medical treatment of such a cold, it is absolutely advisable to be extremely careful and rather cautious. Those affected should refrain from self-treatment altogether and - if at all possible - not consume anything without consulting a doctor. Because almost all active ingredients that are taken during pregnancy also have an effect on the unborn child via the placenta . In the particularly sensitive phase of the first three months of pregnancy, when the individual parts of the child's body develop, it is of great importance that, in the event of unavoidable medication, the active ingredients are taken in their lowest possible dose. Even if a cold has been overcome for a long time, previously taken medication can have a lasting effect on the child's development. It is therefore not uncommon for doctors to rule out the treatment of minor illnesses and complaints even with well-known drugs.

Cold in children

Colds in children are relatively common. If an adult suffers an average of two to three respiratory infections per year, children have up to thirteen flu infections per year.

Statistically, children who attend kindergarten have more colds than schoolchildren. Responsible is the not yet fully developed immune system in children, which learns with every infection: specific antibodies are formed and stored in memory cells.

The increased exposure to pathogens that are transmitted by means of droplet infection by staying in closed rooms with a large number of people also increases the risk of infection.

diagnosis

The diagnosis of a flu-like infection is usually made purely on a clinical basis, i.e. based on the symptoms and a physical examination . In terms of differential diagnosis , a real flu, i.e. influenza -A, -B or -C, and, on the other hand, parainfluenza must be differentiated. In addition, initial infections from herpes viruses ( herpes simplex viruses , cytomegalovirus , Epstein-Barr virus ) in children occasionally run as a flu-like infection. In addition, less severe (abortive) forms of infection with exanthema viruses such as measles , rubella , rubella and varicella are often only flu-like.

Differentiation from real flu (influenza)

The following table compares the typical symptoms of cold and influenza. It must be taken into account that only about a third of those infected with the flu show the typical symptoms, about a third show a mild course, and about a third remain asymptomatic.

| Mark | cold | Real flu (influenza) |

|---|---|---|

| Onset of illness | slow deterioration | rapid, abrupt deterioration |

| a headache | dull to light | strong to boring |

| sniff | often sneezing, runny or stuffy nose | partially occurring |

| fever | mostly low | often high up to 41 ° C, plus chills, sweats. When infected with A / H1N1 (2009), no fever was diagnosed in at least 20% of patients |

| Body aches | low | severe joint and muscle pain |

| to cough | slight urge to cough | dry cough, painful, usually without phlegm |

| Sore throat | often sore throat, hoarseness | strong, with difficulty swallowing |

| fatigue | Exhaustion | difficult, also possible up to three weeks later, loss of appetite, feeling of weakness, circulatory problems |

| Duration of illness | usually 7 days | usually 7–14 days, initially often without any noticeable improvement |

therapy

Therapy conditions

The main thing to treat a cold is to allow the body to rest and to stay in warm, not overheated rooms. If you have a cough or a runny nose, you should primarily follow your natural need to drink, but in no case less than the minimum daily fluid requirement (for an adult: at least 1.3–1.5 l fluid intake via drinks) in the form of water or fruit juice and drinking tea to keep the mucus fluid and to make up for any loss of fluid from the body through sweat, tears, or nasal fluids. It is essential to ensure that they are hydrated, especially with small children. Inhalations can help moisten the mucous membranes and clear them of the mucus. This humidification can also relieve a sore throat and cough. Gargling with warm salt water or rinsing your nose with isotonic salt solution also help . The use of salt for steam inhalation has no effect, as dissolved salt can only get into the air through mechanical action (e.g. spray on wave crests from strong wind or atomizers such as ultrasonic nebulizers ).

Medication

Nasal sprays

A distinction is made between nasal sprays with isotonic or hypertonic saline or sea salt solution as the only active ingredient and those with additional or exclusively synthetic active ingredients. Isotonic saline or sea salt solution (corresponds to the physiological concentration of 0.9%) has a moisturizing, cleansing and slightly rinsing effect and is used to support colds and to prevent the nasal mucous membrane from drying out. Hypertonic saline is supposed to remove excess water from a swollen nasal mucosa by osmotic means and improve the patency of the upper airways. Synthetic nasal sprays are also known as decongestant nasal sprays and should only be used for a short time (usually up to five days), as long-term use leads to drying out and swelling of the nasal mucosa as well as dependency or habituation.

There are also preparations in the form of nasal sprays which are intended to completely prevent the outbreak of the disease, or at least alleviate it by encapsulating the viruses and rendering them harmless. Several randomized double-blind studies emphasize the effectiveness of the finished drug.

Synthetic Medicines

Synthetic drugs with the active ingredients ibuprofen , paracetamol or acetylsalicylic acid usually relieve symptoms such as headache and body aches and also lower the fever, but apart from possible side effects, they also have an undesirable side effect that is based on the effect described: After weakening Due to the symptoms, a patient can feel almost healthy again too soon, then expect too much and thus increase the likelihood of a relapse. In addition, paracetamol has often fallen into disrepute, as it can be used in higher doses. A. Liver damage can occur. The blood-thinning acetylsalicylic acid for this carries a risk of bleeding and should also not be used in children, as it can (although rarely) lead to the dangerous Reye's syndrome . Dextromethorphan or codeine , for example, can be used against particularly strong coughs . Also the pseudoephidrine contained in some combination preparations can v. A. Relieve colds by narrowing the blood vessels.

Antibiotics only work against bacterial infections and are therefore usually not useful in the case of colds. An exception is in the case of a bacterial secondary infection (also called superinfection in this context ) with yellowish-green ( purulent ) sputum or nasal secretions . In patients with an additional underlying disease (e.g. HIV , diabetes mellitus or lung disease ), however, a preventative dose is usually necessary to prevent bacterial superinfection. One cause of the worldwide increase in antibiotic resistance is the improper use of these drugs - also for colds.

Herbal Medicines

Various preparations or teas can be used in the field of rational phytotherapy . Dry extract or Mazerationsdekokt from willow bark ( Salix ) for headaches and / or fever, dry extract or maceration decoction of a mixture of dyed sleeve rootstock ( Baptisia tinctoria ), root of the purple coneflower ( Echinacea purpurea ), root of the pale-colored coneflower ( echinacea pallida ) as well as peaks and Leaves of the tree of life ( thuja ) in viral colds.

Mustard oils made from nasturtium and horseradish root are used in combination for respiratory and urinary tract infections. Numerous in-vitro studies show that the plant substances act against viruses, against bacteria - including the most common pathogens of bacterial respiratory infections and also have anti-inflammatory effects.

Pressed juice from blooming, fresh herb of the purple coneflower is used as a short-term application to prevent or treat colds, thick extract and fluid extract from common horehound and dry extract from thyme herb or infus from thyme leaves to dissolve thick mucus in the airways.

An efficacy of preparations based on pelargonium root extract in the treatment of various colds was determined in a meta-analysis by the Cochrane Collaboration , the quality of the evidence is due to various problems (including manufacturer financing of the studies included, all participants from the same region) as " rated low ”or“ very low ”.

vitamin C

According to a meta-analysis, regular intake of vitamin C had no effect on the incidence of colds in the normal population, but there was an effect on reducing the duration of cold symptoms. With administration of ≥ 0.2 g vitamin C daily, the duration of the illness in adults was reduced by 8%, in children by 14% (by 18% with 1–2 g daily), more pronounced with extreme physical exertion. Giving high doses of vitamin C as a treatment; H. after the onset of symptoms, showed no consistent effect on the duration or severity of cold symptoms.

prevention

In contrast to the flu, there is no vaccination against colds because there are over 300 cold pathogens, so a specific vaccination is of no use. Thus, above all, prophylactic approaches remain. A prevention is u. A. to avoid contact with sick people and their viral cold and cough secretions.

Since the mucous membranes of the nose and eyes are the main entry points for cold viruses, you should not touch your nose with unwashed fingers or rub your eyes. In addition, hand washing should take place after the hands have had direct or indirect contact with other hands, for example after using public transport.

There is no confirmation of successful prevention through high-dose additional intake of vitamin C if there is already an adequate supply of vitamins through a healthy diet. With regard to the effectiveness of preparations made from sun hats ( Echinacea ) or their extracts , there are different study results. One of the reasons for this is that some studies do not state which specific Echinacea species were examined, or results relating to one species are applied to all coneflower preparations. A meta-analysis by the Cochrane Collaboration concludes that the evidence for a clinically relevant effect in therapy is weak overall, but almost all prevention studies included in the meta-analysis indicated a small preventive effect of Echinacea.

A healthy and strengthened immune system can help every person to better fight various pathogens and thus also those of a cold and sometimes also to prevent an outbreak of the disease or to alleviate the symptoms of the disease or to shorten the course of the disease. All measures such as a healthy, balanced diet including all substances necessary for the organism such as minerals and vitamins , sufficient sleep (if possible no less than seven hours per day), the most stress-free daily routine possible, regular exercise or even sporty endurance training and sauna can therefore very well be viewed as preventive measures in the broadest sense, especially since the causers of the common cold are viruses that are strongly adapted to humans.

Of probiotic products is believed to be influenced by effects on immune function health. According to reviews ( meta-analyzes ) that summarize the results of existing studies, the intake of probiotic products in healthy test persons compared to placebo may reduce the likelihood of an upper respiratory tract infection and shorten the duration of infections (according to available findings, on average by 1 day) .

Etymological aspects

In many languages around the world, as in the German term for this disease, a causal connection between the climate factor cold and the common cold is assumed, as the corresponding word for cold or cold appears in the term . This is also the case in many Indo-European languages . In Europe at least the ancient Romans suspected some kind of connection between cold and cold .

In the Latin word for cold frigus , the term frigidus is included for the property cold . Hence also frigore tactum esse for “suffering from a cold”. Most Romance languages adopt this context:

- Italian : freddo ("cold"), raffreddarsi (" catch a cold") , raffreddore ("cold")

- French : froid , se refroidir , refroidissement

- Spanish : frío , resfriarse , resfriado

- Portuguese : frio , resfriado , resfriamento

- Romanian : rece , a răci , răceală

This conceptual context is also present in Slavic languages :

- Polish zimno ("cold"), ziębnąć ("freeze"), przeziębienie (literally: "cold")

- Croatian hladno ("cold"), prehlada ("cold", literally: "excessive cold")

Corresponding to Greek κρύο krýo "cold", (to) kryológima ("cold")

The same applies to Hungarian , one of the Finno-Ugric language families : hűvös, fagy, hideg ("cold"), hűl ("cool down"), fázik ("freeze"), meghűlés, megfázás ("cold")

A conceptual differentiation between the common cold on the one hand and the flu disease on the other hand cannot be demonstrated among the Romans, but it is present in the Romance languages that developed later.

Examples:

- Italian raffreddore 'common cold' ≠ influenza ("flu")

- french refroidissement ≠ flu

- spanish resfriado ≠ gripe

- portuguese resfriamento ≠ gripe

- Romanian răceală ≠ gripă

The modern term influenza for "flu" is from Italian influenza borrowed that on medieval Latin influentia back, derived from classical Latin verb INFLUERE for "flow into, hineinströmen unnoticed penetrate creep". The word flu comes from French, where la grippe is probably a verbal noun to French gripper "to grasp, to grasp".

The colloquial term flu-like infection for colds, which is understandable because of the similarity of symptoms, is basically a confusing combination of the terms flu and cold, which have long been linguistically separated . This indirectly indicates a similarity of the causes, which in reality does not exist, because according to the knowledge of modern medicine the viruses that cause a cold are undoubtedly not flu viruses.

The older term catarrh , actually an inflammation of the mucous membranes, colloquially mostly means a cold. This term for cold can also be found in several Romance languages, for example in Galician and Spanish as catarro and in Corsican as catarru . With Halskatarr (h) one can laryngitis meant.

Web links

- Literature on the subject of colds in the catalog of the German National Library

- Common cold - information at Gesundheitsinformation.de (online offer of the Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care )

- RespVir - network for respiratory viruses and bacteria with information on the frequency distribution and the current epidemiological situation in Germany

- Influenza-like infections (cough, runny nose, sore throat) - kindergesundheit-info.de: independent information service of the Federal Center for Health Education (BZgA)

- Scientific information site on cold (English)

- Cardiff University - Common Cold Center (English)

Individual evidence

- ^ Gustav-Adolf von Harnack, Berthold Koletzko: Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine (= Springer textbook. ). 13th edition. Springer-Medizin-Verlag, Heidelberg 2007, ISBN 978-3-540-48632-9 , p. 374.

- ↑ a b RKI - RKI-Ratgeber - Influenza (Part 1): Diseases caused by seasonal influenza viruses. Retrieved April 13, 2020 .

- ↑ C. Drösser: It's the viruses. In: The time . August 20, 1997.

- ^ Medical Encyclopedia of the US National Library of Medicine: Common cold . On: nlm.nih.gov ; last update: February 2nd, 2016.

- ↑ Upper Respiratory Infections . On: dartmouth.edu - Dartmouth College, Hanover (New Hampshire), USA.

- ^ R. Eccles: Acute cooling of the body surface and the common cold. In: Rhinology. Volume 40, Number 3, September 2002, pp. 109-114. PMID 12357708 (Review).

- ^ R. Eccles: An explanation for the seasonality of acute upper respiratory tract viral infections. In: Acta oto-laryngologica. Vol. 122, Number 2, March 2002, pp. 183-191, PMID 11936911 (review).

- ^ C. Johnson, R. Eccles: Acute cooling of the feet and the onset of common cold symptoms. In: Family practice. Volume 22, Number 6, December 2005, pp. 608-613, doi: 10.1093 / fampra / cmi072 , PMID 16286463 .

- ↑ a b John H. White, Luz R. Tavera-Mendoza: The underestimated sun vitamin. In: Spectrum of Science . July 2008, pp. 40-47.

- ^ LE Tavera-Mendoza, JH White: Cell defenses and the sunshine vitamin. In: Scientific American . Volume 297, Number 5, November 2007, pp. 62-5, 68, ISSN 0036-8733 , PMID 17990825 .

- ↑ Ellen F. Foxman et al. a .: Temperature-dependent innate defense against the common cold virus limits viral replication at warm temperature in mouse airway cells . In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) . tape 112 , no. 3 , p. 827-832 , doi : 10.1073 / pnas.1411030112 .

- ↑ Nadja Podbregar: Corona: Can previous colds protect? On: scinexx.de from July 30, 2020.

- ↑ Nadja Podbregar: Covid-19: Does a previous contact with cold coronavirus protect? On: Wissenschaft.de from July 30, 2020.

- ↑ Miranda de Graaf et al. a .: Evolutionary dynamics of human and avian metapneumoviruses. In: Journal of General Virology. Volume 89, No. 12, December 2008, pp. 2933-2942, doi: 10.1099 / vir.0.2008 / 006957-0 .

- ↑ Data for Germany since 2012, RespVir network.

- ↑ L. Bayer-Oglesby, L. Grize et al. a .: Decline of ambient air pollution levels and improved respiratory health in Swiss children. In: Environmental health perspectives . Volume 113, Number 11, November 2005, ISSN 0091-6765 , pp. 1632-1637. PMID 16263523 , PMC 1310930 (free full text).

- ↑ a b S. Cohen, WJ Doyle et al. a .: Sleep habits and susceptibility to the common cold. In: Archives of internal medicine . Volume 169, number 1, January 2009, ISSN 1538-3679 , pp. 62-67, doi: 10.1001 / archinternmed.2008.505 . PMID 19139325 , PMC 2629403 (free full text).

- ^ A b Aric A. Prather, Denise Janicki-Deverts, Martica H. Hall, Sheldon Cohen: Behaviorally Assessed Sleep and Susceptibility to the Common Cold. In: Sleep. September 1, 2015, Volume 38, No. 9, pp. 1353-1359, doi: 10.5665 / sleep.4968 .

- ↑ Sheldon Cohen et al. a .: Psychological Stress and Susceptibility to the Common Cold. In: New England Journal of Medicine . Volume 325, August 1991, pp. 606-612, doi: 10.1056 / NEJM199108293250903 .

- ↑ Arthur A. Stone, Donald S. Cox, Heiddis Valdimarsdottir, John M. Neale: Secretory IgA as a Measure of Immunocompetence. In: Journal of Human Stress. No. 13, 1987, pp. 136-140, doi: 10.1080 / 0097840X.1987.9936806 .

- ↑ RD Clover et al. a .: Family Functioning and Stress as Predictors of Influenza B Infection. In: Journal of Family Practice. Volume 28, May 1989, ( online ( memento from July 10, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ))

- ↑ Matthew Thompson, Helen D. Cohen, Talley A. Vodicka, et al. a .: Duration of symptoms of respiratory tract infections in children: systematic review. In: BMJ (Clinical research edition). Volume 347, December 11, 2013, p. F7027, doi: 10.1136 / bmj.f7027 . PMID 24335668 .

- ^ How Cold Virus Infection Occurs. On: commoncold.org ; accessed on March 1, 2016.

- ^ JM Harris, JM Gwaltney: Incubation periods of experimental rhinovirus infection and illness. In: Clinical Infectious Diseases . Volume 23, Number 6, December 1996, ISSN 1058-4838 , pp. 1287-1290. PMID 8953073 .

- ↑ Heidelberg University Hospital: Overview of the Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV). (PDF) Section: Duration of virus shedding.

- ↑ Colds in children . ( Memento from January 17, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) In: lifeline.de. 3rd December 2012.

- ↑ New Influenza A / H1N1 in Germany - Assessment of what has happened so far. (PDF). In: Robert Koch Institute : Epidemiological Bulletin . No. 25, June 22, 2009.

- ↑ Colds: What do you think of the advice “drink a lot”? ( Memento from February 1, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) On: Gesundheitsinformation.de , accessed on January 20, 2014.

- ↑ German Society for Nutrition e. V .: The nutritional and physiological importance of water; Guide values for the supply of water On: dge.de accessed on January 20, 2014.

- ↑ German Society for Nutrition e. V .: The reference values for nutrient intake; Water; Guide values for the supply of water; Infants / Children From : dge.de. Retrieved January 20, 2014.

- ^ National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID): Common Cold, Treatment. Archived from the original on April 11, 2014 ; accessed on April 11, 2014 (English).

- ↑ Spray protects against colds and relieves symptoms. Retrieved May 13, 2020 .

- ↑ Deutscher Ärzteverlag GmbH, editorial office of the Deutsches Ärzteblatt: Colds: micro-gel inactivates viruses. October 22, 2004, accessed May 13, 2020 .

- ^ T. Dingermann et al. a .: Compendium Phytopharmaka. Quality criteria and examples of prescriptions. 7th, completely revised edition. Deutscher Apotheker Verlag, Stuttgart 2015, ISBN 978-3-7692-6211-7 , p. 119.

- ↑ Werner Stingl: Fight Influenza Viruses with Phytotherapy. In: Ärzte Zeitung , December 16, 2010.

- ↑ A. Conrad et al. a .: In-vitro studies on the antibacterial effectiveness of a combination of nasturtium herb (tropaeoli majoris Herba) and horseradish root (Armoraciae rusticanae Radix). In: drug research. 2006, Vol. 56, No. 12, pp. 842-849, doi: 10.1055 / s-0031-1296796 .

- ^ V. Dufour et al. a .: The antibacterial properties of isothiocyanates. In: Microbiology. 2015, Volume 161, pp. 229–243, doi: 10.1099 / mic.0.082362-0 .

- ↑ A. Borges et al. a .: Antibacterial activity and mode of action of selected glucosinolates hydrolysis products against bacterial pathogens. In: Journal of food science and technology. 2015, Volume 52, No. 8, pp. 4737-4748, doi: 10.1007 / s13197-014-1533-1 .

- ↑ A. Marzocco, et al. a .: Anti-inflammatory activity of horseradisch (Armoracia rusticana) root extracts in LPS-stimulated macrophages. In: Food & function. 2015, Volume 6, No. 12, pp. 3778-3788, doi: 10.1039 / c5fo00475f .

- ↑ H. Tran u. a .: Nasturtium (Indian cress, Tropaeolum majus nanum) dually blocks the COX an LOX pathway in primary human immune cells. In: Phytomedicine: international journal of phytotherapy and phytopharmacology. 2016, Volume 23, pp. 611–620, doi: 10.1016 / j.phymed.2016.02.025 .

- ↑ ML Lee et al. a .: Benzyl isothiocyanate exhibits anti-inflammatory effects in murine macrophages and in mouse skin. In: Journal of molecular medicine (Berlin, Germany). 2009, Volume 87, pp. 1251-1261, doi: 10.1007 / s00109-009-0532-6 .

- ^ T. Dingermann et al. a .: Compendium Phytopharmaka. Quality criteria and examples of prescriptions. Stuttgart 2015, pp. 110–111.

- ↑ Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products : Community herbal monograph and assessment report on Marrubium vulgare L., herba. European Medicines Agency (EMA) 604273/2012 (2012)

- ^ T. Dingermann et al. a .: Compendium Phytopharmaka. Quality criteria and examples of prescriptions. Stuttgart 2015, pp. 91–93.

- ↑ A. Timmer, J. Günther, E. Motschall, G. Rücker, G. Antes, WV Kern: Pelargonium sidoides extract for treating acute respiratory tract infections . In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. tape 10 , October 22, 2013, doi : 10.1002 / 14651858.CD006323.pub3 , PMID 24146345 (CD006323).

- ↑ Harri Hemilä, Elizabeth Chalker: Vitamin C for Preventing and Treating the Common Cold (Review) . In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews . January 31, 2013, doi : 10.1002 / 14651858.CD000980.pub4 .

- ^ D. Simancas-Racines, JVA Franco, C. V Guerra, ML Felix, R. Hidalgo, M. Martinez-Zapata: Vaccines for the common cold . In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews . No. 5 , 2017, doi : 10.1002 / 14651858.CD002190.pub5 (English, Art. No .: CD002190).

- ↑ Cold season. Bayer HealthCare Germany, August 29, 2011, accessed on January 23, 2017 (press release).

- ↑ a b Jochen Niehaus: Interview: Better to kiss than shake hands. Section: Contagion: The Strategy of the Cold Viruses . On: focus.de , advice from February 6, 2008; Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- ↑ M. Karsch-Völk, B. Barrett, D. Kiefer, R. Bauer, K. Ardjomand-Woelkart, K. Linde: Echinacea for preventing and treating the common cold . In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews . No. February 2 , 2014, doi : 10.1002 / 14651858.CD000530.pub3 (English, Art. No .: CD000530).

- ↑ David C. Nieman1, Dru A. Henson, Melanie D. Austin1, Wei Sha: Upper respiratory tract infection is reduced in physically fit and active adults. In: British Journal of Sports Medicine. (BJSM) September 2011, Volume 45, No. 12, pp. 987-992, doi: 10.1136 / bjsm.2010.077875 , PMID 21041243 .

- ↑ R. Brenke: The potential of the sauna in the context of prevention - an overview of recent findings. In: Researching complementary medicine. 2015, Volume 22, No. 5, pp. 320-325, doi: 10.1159 / 000441402 , PMID 26565984 .

- ↑ Q. Hao, BR Dong, T. Wu: Probiotics for preventing acute upper respiratory tract infections . In: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews . No. 2 , February 3, 2015, doi : 10.1002 / 14651858.CD006895.pub3 , PMID 25927096 (English, Art. No .: CD006895).

- ↑ S. King, J. Glanville, ME Sanders, et al. a .: Effectiveness of probiotics on the duration of illness in healthy children and adults who develop common acute respiratory infectious conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. In: British Journal of Nutrition. (Br J Nutr.) July 2014, Volume 112, No. 1, pp. 41-54, doi: 10.1017 / S0007114514000075 , PMID 24780623 .

- ↑ Influenza . In: Wolfgang Pfeifer: Digital dictionary of the German language. dwds.de; Retrieved May 5, 2016.

- ↑ Influenza . In: Gerhard Wahrig, Ursula Hermann, Arno Matschiner: True dictionary of origin. know.de; Retrieved May 5, 2016.

- ↑ Wolfgang Pfeifer, Wilhelm Braun: Etymological Dictionary of German. 1st edition. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1989, ISBN 3-05-000626-9 and other editions.