Hepatitis B.

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| B16.- | Acute viral hepatitis B |

| B16.0 | Acute viral hepatitis B with Delta virus (accompanying infection) and with coma hepaticum |

| B16.1 | Acute viral hepatitis B with delta virus (accompanying infection) without coma hepaticum |

| B16.2 | Acute viral hepatitis B without delta virus with coma hepaticum |

| B16.9 | Acute viral hepatitis B without delta virus and without coma hepaticum |

| B18.0 | Chronic viral hepatitis B with Delta virus |

| B18.1 | Chronic viral hepatitis B without Delta virus |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

The hepatitis B (formerly also serum hepatitis ) is one of the hepatitis B virus caused (HBV) infection of the liver , often acute (85-90%), sometimes also proceeds chronically. With around 350 million people in whose blood the virus can be detected and in whom the virus is therefore permanently present as a source of infection , hepatitis B is one of the most common viral infections worldwide . Specific antibodies are detectable as a sign of a healed HBV infection in around a third of the world's population . Cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma can develop on the basis of chronic liver inflammation . The treatment of chronic hepatitis B is difficult, so preventive vaccination is the most important measure to avoid infection and reduce the number of virus carriers.

history

A team from the Max Planck Institute at Kiel University has reconstructed the genome of European hepatitis B strains from the Stone Age . For the first time the genome of a prehistoric virus could be obtained. Hepatitis B has existed in Europe for at least 7,000 years. However, the origin and development history of the virus are unknown. The researchers examined samples from the teeth of 53 individuals in Germany. Hepatitis B viruses were discovered in three individuals and the complete genome was recovered. Two are from the Neolithic Age, the third evidence is from the Middle Ages. The genome structure is very similar to that of today's hepatitis B virus.

Pathogen

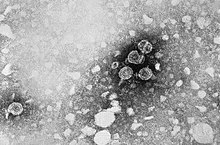

The causative agent of hepatitis B, the approximately 42 nm large hepatitis B virus, is a partially double-stranded DNA virus and belongs to the Hepadnaviridae family . For comparison: red blood cells are 7.5 μm in diameter and around 150 times larger. The approx. 3200 bp genome is packaged in an icosahedral capsid , the hepatitis B core protein (= HBV core antigen, HBcAg). It fulfills a function similar to that of the nucleus in multicellular cells. The capsid is surrounded by a virus envelope made up of a cellular lipid membrane and embedded surface proteins of the virus. These surface proteins ( HBsAg , hepatitis B surface antigen ) exist in three differently sized forms (L-, M- and S-HBsAg). During the multiplication of HBV in the hepatocytes , another protein is usually released into the bloodstream, the HBV-e antigen (HBeAg, "e" is interpreted as " excretory " in relation to the soluble form of the HBV core protein), An antigen is a molecule recognized as foreign by the immune cells; HBeAg is a freshly produced, then shortened, hepatitis B core protein (HBcAg) that is released into the blood by the virus.

Most of the surface proteins in the blood are not involved in the structure of the infectious viruses (the so-called Dane particles), but are in the form of filaments or spherical particles without capsid and DNA (up to 600 μg / ml HBs protein). About 10,000 times more “empty” HBsAg particles can be detected in the blood than complete HBV particles. This has important consequences for the course of the disease. The particles deflect the immune system , similar to a missile defense system in aircraft. To do this, they help diagnose hepatitis B.

The therapy is so difficult because the viruses write their genetic information in the DNA of the hepatocytes. To do this, they use RNA intermediates and, similar to the HI virus, reverse transcriptases ; the HBV is therefore closely related to the real retroviruses . An elimination of the hepatitis B virus from the organism is not possible, the virus DNA is an integral part of the DNA of the liver cells and shares with them. After surviving an acute infection, it goes into a resting state, from which it is reactivated in the event of an immune deficiency (e.g. after organ transplants , chemotherapy or HIV infection).

Because of their similarity to retroviruses, some drugs are effective against both HIV and hepatitis B (the nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors lamivudine and adefovir ).

The RNA intermediate makes the HBV unusually adaptable for a DNA virus. It easily forms variants (so-called quasi - species ) that subvert the immune system or are resistant to antiviral drugs.

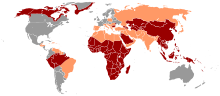

Eight genotypes ( clades ) are known from HBV , which are geographically distributed differently. Type 1 is common worldwide, but especially in the United States , Europe, and China . Types 2 and 4 are mainly found in Japan and Taiwan . Genotype 3 is common in South America. In Africa, on the other hand, types 5, 6, 7 and 8 can be found.

distribution

HBV occurs worldwide. It is endemic to China, Southeast Asia, the Near and Middle East, Turkey, and much of Africa. Thanks to vaccination campaigns that have been carried out for several years, the incidence of chronic virus carriers in northern and western Europe, the USA, Canada, Mexico and southern regions of South America has fallen to below one percent.

In Germany, in a representative population survey carried out from 2008 to 2011 on over 7,000 adults between the ages of 18 and 79 years, 3.9% were classified as immune after the hepatitis B infection had resolved; 0.9% had the infection subsided, but the immune status was unclear, 20.1% were immune after vaccination, 0.5% showed signs of acute or chronic hepatitis B disease.

The official case numbers of the Robert Koch Institute can be found in the list below, whereby the real number is to be set much higher. In Germany there is a lot of sponsorship among intravenous drug addicts, homosexuals and people from the Arab region and Turkey. The latter are often congenital infections. In Eastern and Southern Europe, up to eight percent of the population is chronically infected with HBV. Half of all chronic virus carriers in Germany have a migration background. The number of cases reported to the RKI for Germany has developed as follows since 2000:

| year | reported case numbers |

|---|---|

| 1994 | 5135 |

| 2000 | 4506 |

| 2001 | 2427 |

| 2002 | 1425 |

| 2003 | 1308 |

| 2004 | 1258 |

| 2005 | 1236 |

| 2006 | 1186 |

| 2007 | 1004 |

| 2008 | 817 |

| 2009 | 746 |

| 2010 | 768 |

| 2011 | 811 |

| 2012 | 675 |

| 2013 | 687 |

| 2014 | 755 |

| 2015 | 1943 |

| 2016 | 3034 |

| 2017 | 3609 |

| 2018 | 4503 |

| 2019 | 6386 |

transmission

The infection with HBV is usually parenterally , d. H. through blood or other contaminated body fluids of an infected, HBsAg-positive carrier through injury or sexual contact. The infectivity of a virus carrier depends on the virus concentration in the blood; in so-called highly viremic carriers (10 7 to 10 10 HBV genomes / ml), infectious viruses are also found in urine , saliva , seminal fluid , tear secretions , bile and breast milk .

The entry portals are usually the smallest injuries to the skin or mucous membrane . Therefore, unprotected sexual intercourse is also considered a risk factor. The infection can also be passed on to young children by scratching or biting. Even everyday objects, such as razors or nail scissors, which often cause minor injuries, can transmit HBV. In countries where shaving at the barber's is still widespread, there is usually an increased frequency of HBV infections. Other important transmission options are also major injuries with blood contact z. B. with intravenous drug use, tattooing and piercing . In the medical field, HBV can be transmitted through invasive, surgical interventions and injuries, for example from undetected HBsAg carriers to patients or from untested patients to medical or dental staff. The transmission of HBV through blood and blood products during a transfusion has become very rare in Germany since blood donations were tested for anti-HBc, HBsAg and HBV-DNA.

In endemic areas, the most important route of transmission is vertical infection from an HBsAg-positive mother during childbirth ( perinatal ) to the child. 90% of the perinatal infection results in a chronic infection of the child.

The risk of infection from a needlestick injury with a known HBsAg-positive index patient is around 10–30%. This risk is very dependent on the virus concentration; below 10 5 HBV genomes / ml, such a transmission has not been proven in the medical field. This z. B. the limit already set in Great Britain is of great importance in the employment of HBsAg carriers in the medical field.

Clinical course

Acute hepatitis B

About 2/3 of all infections run without clinical signs (asymptomatic), i. H. After an incubation period of one to six months, only about a third of those infected show the classic signs of hepatitis such as yellowing of the skin and sclera ( jaundice ), dark urine, body aches, pain in the upper abdomen, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea. Often, after asymptomatic courses, a slight fatigue is indicated or an increase in liver enzymes ( transaminases ) is discovered by chance; such an infection can usually only be recognized by serology .

As a rule, uncomplicated acute hepatitis B heals clinically after two to six weeks; the detection of antibodies against HBsAg (anti-HBs) shows this. With the disappearance of HBsAg and the appearance of anti-HBs (seroconversion), the risk of infection is over.

Acute hepatitis B can rarely take a more severe course with high viraemia , in which blood coagulation is impaired and the brain is damaged ( encephalopathy ); therapy with a nucleoside analog (e.g. lamivudine ) or nucleotide analog is recommended here. In the most severe case, around 1% of the symptomatic courses lead to a life-threatening course (in hours to a few days), the so-called fulminant hepatitis . In this case, the rapid disappearance of HBsAg and shrinkage of the liver are considered unfavorable signs; drug therapy and intensive medical care with the option of liver transplantation are required. The administration of interferon is contraindicated in all forms of acute hepatitis B.

Chronic hepatitis B

In many cases, infection with the hepatitis B virus goes unnoticed and without symptoms. By definition, one speaks of chronic hepatitis B if the symptoms of an inflammation of the liver caused by HBV and the corresponding viral markers (positive HBsAg result ) persist for more than six months. This disease is chronic in five to ten percent of cases. It can either develop following acute hepatitis B or it can also be primarily chronic. The rate of chronification is highest in newborns and steadily decreases with increasing age. When infected as described above, newborns become chronic virus carriers in over 90% of cases. Even in four-year-old patients, half of all infections are chronic.

In about a quarter of all chronic hepatitis B diseases, the severity of the disease progresses (progressive), which then often leads to significant consequential damage such as liver cell carcinoma or liver cirrhosis . At the latest when changes in consciousness occur (so-called hepatic encephalopathy ), the patient should be transferred to a center for liver diseases.

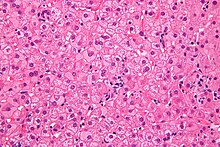

So-called milk glass hepatocytes are histopathologically characteristic of a chronic hepatitis B infection . Due to the hyperplasia of the smooth endoplasmic reticulum (sER, from English smooth ), induced by a massive increase in the viral envelope material (HBs antigen), the cytoplasm of these liver cells appears pale, eosinophilic , finely-grained, homogeneous, frosted-glass-like under the microscope . On the other hand, certain other forms of SER hyperplasia must be differentiated, as they can arise from drug induction ( disulfiram , barbiturates ) or other clinical pictures (e.g. Lafora disease ). In the acute stage of hepatitis B, milk glass hepatocytes are not detectable.

A malignant form after hepatitis B infection has a mortality rate of 0.5–1%. Chronic hepatitis develops in 5–10% of those infected.

About five percent of HBV-infected in addition to hepatitis D ill.

HBV belongs to the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), the hepatitis C virus (HCV), the human papillomavirus (HPV), the human T-lymphotropic virus 1 (HTLV-1) and the human herpes virus 8 (HHV -8, also Kaposi's sarcoma herpes virus, KSHV) to a group of human viruses that are responsible for 10 to 15 percent of all cancers worldwide . It is estimated that approximately 50% of liver cancers are due to HBV. A cohort study in China with around 500,000 participants has shown that chronic hepatitis B disease can also increase the risk of other cancers, particularly cancers of the gastrointestinal tract .

reactivation

Due to new therapies in the treatment of leukemia and for immunosuppression after an organ transplant , a reactivation of an old, clinically healed HBV infection has been observed in individual cases in recent years. Reactivations of HBV in AIDS at an advanced stage (C3) have also been described. In some cases, the HBV infection had already been reactivated decades ago, and the patients previously had the classic serological pattern of an old infection (anti-HBc and anti-HBs positive, see diagnostics). Such a reactivation is often very difficult, especially if, after reactivation, the immunosuppression is reduced and the liver is quickly destroyed by the immune defense, as in fulminant hepatitis. The appearance of such symptoms after reducing the immunosuppression (e.g. after completing chemotherapy or after successful HIV therapy) is also called immune reconstitution syndrome .

Patients after kidney transplantation , bone marrow transplantation and patients with acute myeloid leukemia are particularly at risk from reactivation . Treatment with a nucleoside analog for several weeks to months is advisable if reactivation has been proven.

The reactivation phenomenon illustrates once again the fact that HBV, like a real retrovirus, can go into a dormant state and is not eliminated from all cells. Overall, however, reactivation is a very rare occurrence.

diagnosis

There are two main forms of hepatitis B, acute hepatitis B, which is completely healed after six months at the latest, and chronic hepatitis B. Chronic hepatitis B arises from an acute one that has not healed, can last for decades and cirrhosis of the liver or one Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The respective diagnosis is backed up via three main components that are searched for:

- Virus antigens (i.e. the virus itself or its proteins ): If virus antigens (HBs-Ag, HBe-Ag) are still found, then the infection is not over: acute or chronic hepatitis B will be present, or in the best case if only HBs-Ag is detectable and the patient is otherwise healthy, a so-called HBs carrier status. Patients with HBe-Ag in their blood are highly contagious; but even with HBs-Ag alone in the blood there is a risk of infection.

- Antibodies (which form our defense against it): Anti-HBs are signs of healing. They can also be found after a successful hepatitis B vaccination. So they indicate immunity to hepatitis B. Anti-HBc-IgM suggest the presence of acute hepatitis. Anti-HBc-IgG can be found both in the later acute stage and after healing. Anti-HBe can occur during the healing phase of acute hepatitis. Their occurrence in chronic hepatitis indicates an improvement and a reduced risk of infection.

- Virus DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid, i.e. genetic material of the virus): In the past, DNA measurement was used in hepatitis B to diagnose unclear cases and to assess the risk of infection. Today, measurement is also important for diagnosing and monitoring chronic hepatitis. Little viral DNA in the blood suggests a dormant infection, a lot of DNA suggests active chronic hepatitis.

| anti-HBc | anti-HBs | HBs antigen | anti-HBe | HBe antigen | HBV DNA | interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| neg. | pos. | (neg.) | (neg.) | (neg.) | (neg.) | Condition after vaccination |

| pos. | pos. | (neg.) | (neg./pos.) | (neg.) | (neg.) | old, clinically healed infection |

| pos. | (neg.) | pos. | neg. | pos. | high pos. | highly viremic infection |

| pos. | (neg.) | pos. | pos. | neg. | pos. | low viremic infection |

| pos. | (neg.) | pos. | neg. | neg. | high pos. | “HBe minus mutant”, pre-core mutation |

| anti-HBc | anti-HBs | HBs antigen | anti-HBe | HBe antigen | HBV DNA | interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pos. | neg. | neg. | neg. | neg. | neg. | “Isolated anti-HBc positivity”: unspecific test reaction or very old, healed infection |

| pos. | neg. | neg. | pos. | neg. | neg. | old, healed infection with loss of anti-HBs or unspecific cross-reactivity |

| neg. | pos. | pos. | neg. | neg. | neg. | mostly unspecific test reaction of the HBsAg test or very rarely results a few days after a repeated vaccination |

| neg. | neg. | pos. | neg. | neg. | pos. | Missing anti-HBc: Frequent constellation in the case of infection of a non-immunocompetent person or of congenital infection |

therapy

In the acute stage (i.e. in the first few months after infection), hepatitis B is usually only treated symptomatically, as the disease heals by itself in 90-95% of cases.

Two drug classes are available for chronic hepatitis B:

- Interferon alpha ( 2-a or 2-b) , preferably pegylated interferon (peginterferon) alpha 2-a , which is injected once a week. Interferons stimulate the immune system so that it fights the virus more effectively.

- Nucleoside or nucleotide analogs that are taken daily as tablets. These include lamivudine , adefovir , entecavir , telbivudine, and tenofovir . These active ingredients prevent the virus from multiplying.

Other active ingredients are being tested in studies. However, these therapies are not curative , so a complete elimination of the virus is not to be expected. Rather, the aim of therapy is to alleviate the course of chronic hepatitis B and lower the risk of long-term effects. Rarely (up to three percent) during therapy with (peg) interferon or the other active ingredients, HBsAg can also disappear from the blood and anti-HBs antibodies appear as an immune reaction, which is equivalent to a cure.

Which patient needs to be treated when and with which medication varies from case to case. If the course is very mild, chronic hepatitis B is usually only observed. If there is evidence of damage to the liver or other risk factors, therapy is very important (as of August 2008). This should be assessed by a specialist in each individual case.

Chronic active hepatitis B must be treated, in which the HB viral load is greater than 2000 IU / ml, an increase in transaminases (a liver function parameter) by more than double, histologically showing inflammatory activity and sonographically, biopsy or through Fibroscan fibrosis or cirrhosis of the liver is evident. If these diagnostic criteria do not exist, those affected are referred to as inactive carriers and only one observation is initially required.

vaccination

You can vaccinate actively and passively against hepatitis B. Active vaccination consists of a component of the virus envelope, the HBs antigen, which is genetically expressed in yeast cells. The body becomes active, building defense molecules (immunoglobulins) against foreign substances in order to destroy them. After three vaccinations, the immune cells know what the virus is and can fight it if there is a real infection. Contrary to other opinions, the hepatitis B vaccination does not give real viruses. The number of non-responders is well below ten percent. Vaccination is carried out three times:

- Vaccination (week zero)

- Vaccination (about a 1 month later)

- Vaccination (six months to a year after the first vaccination)

To check the success of the vaccination, anti-HBs should be determined 4–8 weeks after the 3rd vaccine dose (successful vaccination: anti-HBs ≥ 100 IU / l). After a successful vaccination, no further booster vaccinations are required (exception: patients with immunodeficiency, possibly people with a particularly high individual risk of exposure).

With passive vaccination, hyperimmunoglobulins are injected; ready-made immunoglobulins that help the immune system fight the viruses. This is administered together with an active vaccine after contact with infected material (post-exposure prophylaxis , especially in the hospital: needle injuries, contact with the mucous membrane, etc., with active vaccination if anti-HBs below 100 and the administration of immunoglobulin if anti-HBs below 10 IU / L) and in newborns of hepatitis B-positive mothers up to 12 hours after contact or birth. This vaccination protection is completed for newborns according to the normal vaccination schedule (0th - 1st - 6th month). This creates an immune response in more than 95% of the vaccinees.

Since you can only get infected with hepatitis D if you already have hepatitis B, the hepatitis B vaccination also protects against hepatitis D viruses. There is also a combination vaccine that protects against hepatitis A. The vaccination is generally well tolerated. Occasionally there is redness at the vaccination site. Fever, headache, fatigue and joint problems are less common. Vaccine damage or severe allergic reactions are very rare. A causal connection with neurological diseases (e.g. Guillain-Barré syndrome ) has not yet been clarified; there are individual case reports in which a coincidental coincidence is suspected. If there are acute illnesses or other contraindications, e.g. For example, if a component of the vaccine is not tolerated or if you have a febrile illness, you should not vaccinate.

Whether unsymptomatic multiple sclerosis can be triggered by the HBV vaccination has repeatedly been discussed in studies and individual case reports. However, it has not yet been scientifically proven. A 2004 study reportedly found a three-fold increased risk of MS from HBV vaccination; However, it was criticized (among others by the World Health Organization WHO) as misleading and not meaningful because of methodological errors: In the study, only MS patients were asked how many of them were vaccinated against hepatitis B in the three years before their MS diagnosis (this only applied to eleven of the original 713 MS patients). The number of healthy people who had been vaccinated against hepatitis B and did not develop MS was not examined to provide a framework for comparison.

In 1992 the World Health Organization called on all member states to include hepatitis B vaccination in national routine vaccination programs. In Taiwan, universal HBV vaccination has significantly reduced the rate of liver cancer.

Germany

A vaccination (active immunization) is for all infants and children from the Standing Committee on Vaccination ( STIKO recommended), namely since 1995. In addition, individuals should in hospitals and nursing professions and undertaker, Thanatologen and corpse scrubber , employees in pathology, dialysis patients , Promiscuous , Drug addicts and travelers to risk areas do not do without vaccination protection. The hepatitis B vaccination is a health insurance benefit for children, adolescents and people who belong to a risk group; some health insurances reimburse the cost of a travel vaccination as a statutory benefit.

Austria

In Austria, the basic vaccination is carried out for all infants from the third month of life - usually with a sixfold combined vaccine - otherwise the basic vaccination is carried out for the previously unvaccinated children as part of the school vaccination at the age of eleven. It is assumed that after a complete primary immunization (in responders) protection against complications of a hepatitis B infection is guaranteed by reactivating the specific memory cells, even if the vaccine antibodies have disappeared. School vaccinations against hepatitis B should therefore be dispensed with when the first vaccinated infants have reached this age, as experts currently do not recommend a booster vaccination for young people who are vaccinated.

Reporting requirement

In Germany, all acute viral hepatitis (including acute hepatitis B) must be reported by name in accordance with Section 6 of the Infection Protection Act (IfSG) . This concerns the suspicion of an illness, the illness and death. In addition, any evidence of the hepatitis B virus must be reported by name according to § 7 IfSG.

In Austria, after § 1 1 para. Epidemics Act 1950 of suspicion, illness and deaths from infectious hepatitis (hepatitis A, B, C, D, E) , including hepatitis B, notifiable .

Also in Switzerland is subject to hepatitis B of the reporting requirement and that according to the Law on Epidemics (EpG) in connection with the epidemic Regulation and Annex 1 of the Regulation of EDI on the reporting of observations of communicable diseases of man . Meldekritien for this message by doctors, hospitals, etc. are a positive laboratory analytical finding and the request by the cantonal doctor or the cantonal medical report the case. Laboratories must report positive laboratory results for the hepatitis B virus in accordance with Appendix 3 of the above-mentioned EDI ordinance.

literature

- S3 guideline for hepatitis B virus infection - prophylaxis, diagnostics and therapy of the German Society for Digestive and Metabolic Diseases (DGVS). In: AWMF online (as of January 31, 2011)

- Baruch S. Blumberg : Hepatitis B: the hunt for a killer virus. Princeton 2002.

- Archeology in Germany (AiD) 04/2018, p. 4.

- Hartwig Klinker: Virus infections. In: Marianne Abele-Horn (Ed.): Antimicrobial Therapy. Decision support for the treatment and prophylaxis of infectious diseases. With the collaboration of Werner Heinz, Hartwig Klinker, Johann Schurz and August Stich, 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Peter Wiehl, Marburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-927219-14-4 , pp. 297-299.

- Wolfram H. Gerlich: Medical Virology of Hepatitis B: how it began and where we are now . In: Virology Journal . tape 10 , 2013, ISSN 1743-422X , p. 239 , doi : 10.1186 / 1743-422X-10-239 , PMID 23870415 .

Web links

- Hepatitis B - information from the Robert Koch Institute

- Website of the National Reference Center for Hepatitis B and D Viruses ( Institute for Medical Virology Giessen )

- Competence network hepatitis

- Hepatitis B diagnostics . Laboratory dictionary

- Vaccination recommendation of the Stiko. (PDF) Epidemiological Bulletin 36/2013

- Hepatitis B at www.aidshilfe.de der Deutschen AIDS-Hilfe e. V.

Individual evidence

- ↑ B. Krause-Kyora, J. Susat, FM Key et al .: Neolithic and medieval virus genomes reveal complex evolution of hepatitis B. eLife 7, 2018, 500. doi 10.7554 / eLife.36666

- ↑ Gholamreza Darai, Michaela Handermann u. a .: Lexicon of Infectious Diseases. 4th edition. Springer, 2011, ISBN 3-642-17158-3 , p. 372. Limited preview in Google book search

- ↑ Doctors' newspaper: Healing after hepatitis B therapy? .

- ↑ incorrectly also as "envelope" and "early"; see. see Medical Virology of Hepatitis B: how it began and where we are now . PMC 3729363 (free full text)

- ↑ A. Erhardt, WH Gerlich: Hepatitis B virus. In: Wolfram H. Gerlich (Ed.): Medical Virology. 2nd edition, Georg Thieme Verlag, 2010, ISBN 3-13-113962-5 , p. 373. Limited preview in the Google book search

- ↑ C. Poethko-Müller, R. Zimmermann, O. Hamouda, M. Faber, K. Stark, RS Ross, M. Thamm: The Seroepidemiology of Hepatitis A, B and C in Germany Results of the Study on Adult Health in Germany ( DEGS1) . (PDF; 610 kB) In: Federal Health Gazette - Health Research - Health Protection 56: pp. 707–715 (2013).

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 3 of the RKI (PDF) January 23, 1996.

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 3 of the RKI (PDF) January 18, 2002.

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 3 of the RKI (PDF) January 17, 2003.

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 2 of the RKI (PDF) January 16, 2004.

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 2 of the RKI (PDF) January 14, 2005.

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 3 of the RKI (PDF) January 20, 2006.

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 3 of the RKI (PDF) January 19, 2007.

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 3 of the RKI (PDF) January 18, 2008.

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 3 of the RKI (PDF) January 19, 2009.

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 3 of the RKI (PDF) January 25, 2010.

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 3 of the RKI (PDF) January 24, 2011.

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 3 of the RKI (PDF) January 23, 2012.

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 3 of the RKI (PDF) January 21, 2013.

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 3 of the RKI (PDF) January 20, 2014.

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 3 of the RKI (PDF) January 19, 2015.

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 3 of the RKI (PDF) January 20, 2016.

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 3 of the RKI (PDF) January 18, 2017.

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 3 of the RKI (PDF) January 17, 2018.

- ↑ Epidemiological Bulletin No. 3 of the RKI (PDF) January 17, 2018.

- ↑ a b Epidemiological Bulletin No. 3 of the RKI (PDF) January 16, 2020.

- ↑ a b Hartwig Klinker: Akute Hepatitis B. 2009, p. 297.

- ↑ a b Helmut Denk , HP Dienes et al .: Pathology of the liver and biliary tract . Springer, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-642-62991-4 .

- ^ Henryk Dancygier: Clinical hepatology: Basics, diagnostics and therapy of hepatobiliary diseases . Springer, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-540-67559-0 .

- ↑ Herbert Hof, Rüdiger Dörries: Medical Microbiology. 4th edition. Georg Thieme Verlag, ISBN 3-13-125314-2 .

- ↑ D. Martin, JS Gutkind: Human tumor-associated viruses and new insights into the molecular mechanisms of cancer . In: Oncogene . 27, No. 2, 2008, pp. 31-42. PMID 19956178 .

- ↑ Massimo Levrero, Jessica Zucman-Rossi: Mechanisms of HBV-induced hepatocellular carcinoma . In: Journal of Hepatology . tape 64 , 1 Suppl, April 2016, ISSN 1600-0641 , p. S84 – S101 , doi : 10.1016 / j.jhep.2016.02.021 , PMID 27084040 .

- ^ Ci Song et al .: Associations Between Hepatitis B Virus Infection and Risk of All Cancer Types . In: JAMA network open . tape 2 , no. 6 , June 5, 2019, ISSN 2574-3805 , p. e195718 , doi : 10.1001 / jamanetworkopen.2019.5718 , PMID 31199446 , PMC 6575146 (free full text).

- ↑ Hartwig Klinker: Acute Hepatitis B. 2009, p. 297.

- ↑ RKI - Epidemiological Bulletin 34/2015 rki.de (PDF)

- ^ Marianne Abele-Horn: Antimicrobial Therapy. Decision support for the treatment and prophylaxis of infectious diseases. With the collaboration of Werner Heinz, Hartwig Klinker, Johann Schurz and August Stich. 2nd, revised and expanded edition. Peter Wiehl, Marburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-927219-14-4 , p. 322 f.

- ↑ H. Renz-Polster, S. Krautzig: Basic textbook internal medicine 4th edition, 2006, p. 649 ff.

- ↑ a b c M. Cornberg, U. Protzer: Prophylaxis, diagnosis and therapy of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection . In: Journal of Gastroenterology . tape 45 , no. 6 , June 2007, p. 525-574 , doi : 10.1055 / s-2007-963232 , PMID 17554641 ( PDF ( memento of February 1, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) [accessed November 9, 2016]). Prophylaxis, diagnosis and therapy of the hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection ( Memento of the original from February 1, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ MA Hernán, SS Jick u. a .: Recombinant hepatitis B vaccine and the risk of multiple sclerosis: a prospective study . In: Neurology . tape 63 , no. 5 , September 2004, ISSN 1526-632X , p. 838-842 , PMID 15365133 .

- ↑ World Health Organization: Programs and Projects: Hepatitis B. (English).

- ↑ MH Chang, SL You et al. a .: Decreased incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis B vaccinees: a 20-year follow-up study. In: Journal of the National Cancer Institute. Volume 101, Number 19, October 2009, pp. 1348-1355, doi: 10.1093 / jnci / djp288 . PMID 19759364 .

- ↑ www.frauenaerzte-im-netz.de ( Memento of the original from April 7, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ↑ Hepatitis B vaccination: is the duration of vaccination protection sufficient to consider vaccination in infancy? according to "Medecine et Enfance" 2001 ( memento of the original dated December 30, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .