Croesus

Croesus ( Greek Κροῖσος . Kroîsos , Latin Croesus ) (* around 590 BC; † around 541 BC or later) was the last king of Lydia , located in Asia Minor . He ruled from about 555 BC. BC to 541 BC And was best known for his wealth and generosity.

Sources

There are numerous references from Greek and Latin authors who wrote about Croesus. However, it is very difficult to extract the real core and to reconstruct a historically reliable biography of the last Lydian ruler. There are no known mentions of Croesus in contemporary sources. His name does not appear either in the cuneiform texts that have appeared so far or in the few known Lydian inscriptions. In 2019, David Sasseville and Katrin Euler published an investigation into coins from Lydia apparently minted during his reign, with the ruler's name being rendered as Qλdãns . Possible own inscriptions of the Lydian king represent three very badly mutilated Greek reports that were found in the temple of Artemis in Ephesus on fragments of the column base.

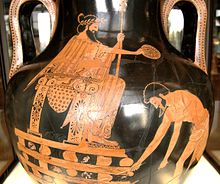

The oldest surviving portrait of Croesus, which depicts him at the stake, is on a c. 490 BC. Made amphora of Myson . The similar motif of “heroic self-immolation” can also be found in the poems of Bakchylides , discovered in 1896 , whose origin dates back to 468 BC. Is dated, thus representing the oldest written mention of Croesus. The last Lydian king is characterized more negatively in the oldest surviving historical work, that of the Greek historian Herodotus , who is the main source for both his life and the history of Lydia in general. Then Croesus is mentioned in the historically hardly usable work Education of Cyrus ( Kyroupadie ) by the Greek historian Xenophon , as well as in a preserved fragment of Persica (Περσικά) by Ktesias of Knidos , which is also weak .

The probably reliable work of the Lydian historian Xanthos , on which two excerpts dealing with Croesus from the world history of Nikolaos of Damascus may be based, has been lost. Nikolaos most likely used Ktesias as an additional source for his narrative. The fragment of Diodorus reporting on the Lydian king probably goes back to Ephorus . Finally, there are also references to Plutarch , Justinus and many later authors.

Origin and family

Croesus, from the Mermnaden dynasty , was the eldest son of Alyattes II , the fourth Lydian king of this family, and a Carerian woman who was not known by name . Alyattes had other sons with other women, such as a Pantaleon with an Ionian of unknown name. Croesus probably also had a brother named Adramyttos , who is said to have founded the city of Adramytteion . Of the two mentioned sisters of Krösus the one that was Aryenis , due to a Peace Treaty between Alyattes and Kyaxares II. , The ruler of the Meder , the wife whose son, the Astyages . The other sister, not mentioned by name, married a Melas , whose son Pindarus , who later became the tyrant of Ephesus , was.

The Greek historians do not mention the name of the wife of Croesus, but at least a son who was therefore called Atys . A second, mute or deaf-mute son is not named, who only began to speak when his father was threatened with execution after the Persians took Sardis . According to Xenophon, Croesus also had some daughters.

Reign and dates of life

According to Herodotus, Croesus ascended the throne at the age of 35 and ruled for 14 years and 14 days before he was overthrown by the Persian king Cyrus II . He is said to have been pardoned and even experienced the conquest of Egypt by Cyrus' son Cambyses II . According to the Chronicle of Eusebius of Caesarea , Croesus ruled for 15 years from 560 to 546 BC. The end of the Lydian empire was also set by Diogenes Laertios , Hieronymus and Solinus in the 58th Olympiad (548 to 545 BC), Diogenes Laertios referring to Sosicrates of Rhodes , while the marble Parium put the end to 541/540 BC . Dated.

In the Nabonaid chronicles for the year 547 BC The campaign of Cyrus II mentioned earlier was mostly related to Lydia, hence Croesus' fall to 547 BC. Dated BC, but because of the rereading of the cuneiform texts, modern research now takes the view that this entry in the chronicle relates to a war against Urartu , and that Cyrus II did not invade Lydia until later. According to this finding, in accordance with the indication of the marble Parium , Croesus' reign is estimated to have ended in the year 541 BC. Dated. Taking into account other dates given by Herodotus and Eusebius, Croesus was named around 591 BC. Born in BC, ruled around 555 to 541 BC. And died either in the latter year or, according to Herodotus, not until after 526 BC. Chr.

Croesus as Crown Prince

According to the fragment of Nikolaos of Damascus, Croesus was appointed governor of Adramytteion by the father . Disapproving people defamed him to their father. In order to get rid of the accused blame, he planned to participate independently in a campaign of the father against Karien. However, the necessary funds were missing, which the merchant named Sadyattes, who was considered to be the richest Lydian, wanted to advance him. This rejected the request extremely rudely. Nevertheless, Croesus received considerable sums of money, given by an Ionian friend named Pamphaes , who in turn had received them from the wealthy father Theocharides . With the mercenary army recruited in this way , he took part in the war against Caria. In doing so, he was able to thwart the plans of his detractors.

Herodotus also reports that there were attempts to dispute Croesus' rights to the succession to the throne. A man generally referred to as an enemy by the Greek historian is said to have endeavored to ensure that Croesus' half-brother Pantaleon would succeed Alyattes on the throne. Plutarch reports, however, that Alyattes 'second wife sought after Croesus' life. She wanted to realize her murder plan with poisoned bread, but it was thwarted by a warning from a baker. The bread intended for him is said to have given Croesus to the children of his stepmother to eat.

The opinion is often found in research that the enemy of Croesus, not named by Herodotus, and the Sadyattes led by Nikolaos of Damascus are identical, since, according to the reports of the two historians mentioned, both suffered similar punishments after Croesus' accession to the throne. According to Nikolaos of Damascus, Sadyattes was completely expropriated; Croesus dedicated his confiscated belongings to Artemis , while he allegedly rewarded his helper in need, Pamphaes, with a truckload of gold. According to Herodotus, Croesus took a similar action towards his enemy by offering his property as a consecration gift to Artemis of Ephesus and the Branchides. According to Herodotus, the enemy also suffered a painful death. Plutarch tells that after Croesus took over the rule, he honored the baker who was helpful to him by making a golden picture designed after her, and Herodotus claims to have seen such a three ells high picture of the baker in Delphi as a dedication by Croesus.

government

By the time Alyattes died, Croesus had perhaps been his co-regent for a while and succeeded him in rule over Lydia according to Alyattes' orders. He greatly expanded his empire through wars and, according to Herodotus, attacked Ephesus as the first Greek city . There his nephew Pindarus ruled as a tyrant . This is said to have connected the city gates and walls with the columns of the Temple of Artemis with ropes and thus placed the city under the care of the goddess Artemis. Since the Lydian ruler was bound by an oath to this temple, he left Ephesus unscathed and gave the city its freedom. However, his nephew had to go into exile in the Peloponnese on his orders .

According to the chronology of Herodotus, Croesus subjugated all the mainland cities of the Ionians and Aiolians after his attack on Ephesus . Then he went to advance the shipbuilding in order to be able to subjugate the Greek islands. But he failed to do this - allegedly on the wise advice of the Bias of Priene or (chronologically impossible) of the Pittakos of Mitylene - and instead entered into a friendship treaty with the Greek islands. As a result, Croesus subjugated the entire western half of mainland Asia Minor. His empire extended to the Halys river , which in its upper reaches at Mazaka / Pteria? (today Kayseri) formed the border to the media ruled by Astyages . According to Herodotus, under his rule were a. a. Phrygians , Thracians , Bithynians , Carians , Ionians, Dorians , Aetolians and some other nations. Cilicia and Lycia did not belong to his kingdom.

In the war practice , Croesus followed old traditions. For example, tried and tested oracles were questioned , and the designated heir to the throne was often the actual leader of the war. Tactically, the Lydians mostly sought victory in open field battles. The punishment of captured cities was often severe; sometimes the exile of its inhabitants followed and the city was cursed. In any case, the latter measure affected the city of Sidene am Granikos in Mysia . For that is where the tyrant Glaucias had fled, and after its conquest Croesus had the city devastated and cursed forbidding its being restored. Otherwise, only a few details are known of the campaigns of Croesus. When Miltiades the Elder was captured by the inhabitants of Lampsakos , they were so intimidated by the Lydian king that they released Miltiades into freedom.

Croesus was the first monarch in Asia Minor to whom the Greek cities there regularly had to pay taxes . Before his time, only looting and tribute collections took place. Probably the subjugated countries also had to provide contingents for Lydian campaigns. Only Ephesus and Miletus received better conditions; the Milesians were even his allies. Ilish and Ephesian populations were transplanted from the hills into the valleys; it is unclear whether this measure was voluntary or under pressure from Croesus. Otherwise the Lydian king does not seem to have interfered further in the internal affairs of the countries under his control.

In the area of religious policy, Croesus was very generous towards the temples of Artemis at Ephesus and Apollo at Didyma and also donated generous gifts of consecration to Delphi. The Artemision at Ephesus was also allowed to retain its ancient Anatolian character.

Fight against Cyrus II and fall

First military confrontation at Pteria

After Cyrus II. 550 BC BC that Lydia had conquered neighboring media and carried out further successful campaigns, Croesus felt threatened by the seemingly overpowering Persian king. At the same time he wanted to take revenge on the Persians for the overthrow of his brother-in-law Astyages and enlarge his own Lydian territory at the expense of their newly established empire. Herodotus names these three reasons as the main reason for Croesus' war initiative against Cyrus II. Before taking to the field, he allied himself with Sparta , the Babylonian king Nabonaid and Amasis of Egypt .

However, Croesus suffered a setback right from the start of his company. He had given the Eurybatos from Ephesus a large sum of money in order to use it to hire a mercenary force in the Peloponnese. Instead, Eurybatos brought these treasures to the Persian king. Nevertheless, the wise counsel of the Lyders could Sandanis Croesus not deter from his military projects. But before he started his offensive, he consulted the Oracle of Delphi . This gave him the ambiguous prophecy:

“ If you cross the Halys, you will destroy a great empire. "

The Lydian king is said to have taken this prophecy in a positive sense and was therefore encouraged to attack the neighboring Persian Empire. So he crossed the border river Halys and invaded Cappadocia . The story that Croesus only succeeded in crossing the river because, on the wise advice of the Valley of Miletus, allowed the Halys to drain into a moon-shaped ditch dug behind the Lydian camp site, was rejected as untrustworthy by the father of historiography. After taking the metropolis of Pteria, Croesus also devastated the neighboring towns and had the inhabitants carried away as slaves.

But Cyrus II soon approached the theater of war with a strong force. He urged the Ionians to fall away from the Lydians and go over to him. But the Greeks did not obey this order; only Miletus refused to enter the army against the Persians and was therefore granted the same favorable conditions after their victory as the only Greek town in Asia Minor that it had previously enjoyed under the Lydians. According to the Sicilian historian Diodorus , however, Cyrus is said to have had heralds inform Croesus that he should go to him and recognize Persian suzerainty; then he would forgive him and let him continue to rule as governor of Lydia. Of course, the Lydian king refused to comply with such a degrading demand and responded with a correspondingly hurtful negative answer.

In any case, the first military confrontation between the two kings took place at Pteria . There were many casualties on both sides, but the battle was still undecided when it was dawn. It was therefore ended for the time being, but Cyrus is said not to have faced another fight the next day. However, the following retreat of the Lydian king to Sardis was more likely the result of a defeat. Since he apparently no longer expected further fighting this year, he dismissed the foreign troops. He also called on his allies to send reinforcement troops to him in five months' time so that, with this support, he could renew the military confrontation with Cyrus next year.

Taking Sardis

But Cyrus did not hesitate long and followed Croesus with his army in forced marches. Since the Lydians were good riders and fought skillfully on horseback, Croesus now sent Lydian cavalry units to meet the Persian army . On the advice of his Median general Harpagos , Cyrus is said to have placed riders on camels at the head of his troops, since horses couldn't stand the smell of camels. With this ruse the Lydian cavalry was defeated in front of the city gates of Sardis and the Persians now proceeded to the siege of the city. But Croesus managed to send messengers to his allies again with the request for auxiliary troops.

According to Herodotus, Sardis was captured by the Persians after a two-week siege. According to this historian, the conquest came about through a surprise effect. A Lydian soldier climbed down and up again on a steeply sloping side of the castle rock that was considered to be inaccessible to retrieve the helmet that had fallen down. A marten by the name of Hyroiades observed this incident and climbed the castle rock at the same point with many other courageous Persians the next day. So Sardis was conquered. That of the historian Xenophon is only a modification of this account by Herodotus. In contrast, the fragment of Ktesias that has survived differs greatly from this narrative. It reports that the Persian king allegedly took a son of Croesus hostage before conquering Sardis. But since the Lydian king had unfaithful intentions towards Cyrus, the Persian king is said to have had Croesus' son killed, and his parents should have watched. His mother could not stand this, but jumped down from the city wall. The Persians would then have held replica wooden dolls on poles over the top of the wall of Sardis and thus caused panic among the besieged, so that the city fell into the hands of Cyrus.

The further fate of Croesus

The Lydian Empire went with the conquest of its capital in 541 BC. Chr. To the end. Due to the widely divergent representations of the Greek historians about the fate of Croesus, it should no longer be possible to determine with certainty whether he was amnestied or killed by Cyrus. The latter variant reports Eusebius of Caesarea, while Croesus survived according to the statements of the other authors. The extreme opposite to Eusebius can be found in Xenophon's depiction: When Croesus was captured, a friendly conversation had developed between Cyrus and the Lydian king, and Croesus accompanied the Persian king everywhere as an advisor.

According to all other reports except Eusebius and Xenophon, Croesus was in mortal danger after the conquest of Sardis, from which he was freed by the intervention of heavenly powers. The oldest surviving informant, Bakchylides, reports that Croesus planned his self-immolation together with his family after the fall of Sardis. That is why he stood with his wife and daughters on a pyre built in front of his palace and prayed to the gods. But when a servant lit the fire at his command, Zeus extinguished it with a rapidly falling rain and Croesus and his family were raptured by Apollo to the Hyperboreans . This story is pictorially implemented on an old vase picture. You can see the magnificently decorated Croesus sitting on an armchair positioned at the top of a pyre, while a servant apparently lights the wood with a torch.

The story of Herodotus states that after the fall of the Lydian capital, a Persian soldier wanted to kill Croesus because he did not know who it was. The up to then speechless son of Croesus suddenly began to speak in view of the impending danger in which his father found himself and asked the soldier to spare Croesus. The former Lydian ruler was not killed immediately, but brought before the victorious Persian king, who gave the order to be cremated. At the stake, Croesus remembered Solon's warning that the wise man had once addressed to him during a visit: “ Nobody can be made happy before his death. “Now he called the wise man's name three times, which Cyrus could not explain. He demanded clarification from Croesus, who at first refused, but then reported on his earlier meeting with Solon. The Persian king then ruefully withdrew his execution order, but the flames could no longer be extinguished. Now, in his distress, Croesus pleaded with the god Apollo , whom he greatly admired , who quickly turned the weather from a clear sky to a downpour, so that the flames went out. The Lydian king was now allowed to leave the stake and won Cyrus for himself with clever words.

This depiction of Herodotus was one of the models for the surviving fragment of Nikolaos of Damascus, which, however, provides additions from another source and generally makes the plot more dramatic. The prophecy sibyl appears with him with a warning to the Persians as well as the mention of the prohibition of the Persian prophet Zoroaster to cause pollution of the fire by burning people. The account of Ktesias is quite fabulous, in which there is no pyre, but which speaks of a miraculous, repeated release of Croesus from his bonds, so that the Persian king finally granted him amnesty.

There is only sporadic information about Croesus' further life after his alleged pardon. According to Herodotus' report, Croesus was accompanying the Persian king from his conquered residence Sardis to Ekbatana when the news of the rebellion of the defeated Lydia arrived. In this connection Croesus gave Cyrus the advice and the request to forgive the Lydians and only to disarm them, but not to enslave them. On the other hand, Croesus' advice to fight the massage queen Tomyris in her country was disastrous for Cyrus because the Persian king 530 BC. Died in this war. But Croesus and Cambyses II , who had been chosen as heir to the throne, escaped alive from this campaign , because Cyrus had sent them home to Persia before the fatal battle against Tomyris for him. Allegedly, Croesus also took 526 BC. In the victorious campaign of Cambyses against Egypt and was present at the conquest of Memphis . When Cambyses later asked the Persians present to compare him with his father, his compatriots flattered him, but Croesus noticed that he was missing an heir to the throne (such as Cambyses) for the size of Cyrus; The Persian king is said to have been pleased about this answer. But when Croesus reprimanded Cambyses' despotic behavior and some misdeeds, the latter became angry and wanted to shoot him with a bow. But the former Lydian king managed to escape and he was hidden by some servants. When Cambyses longed for Croesus again, he was informed of his survival. The Persian king was happy, but had the servants who had helped Croesus executed. Herodotus gives no information about the circumstances of Croesus' death.

According to Ktesias, Croesus would have become ruler of the important city of Barene , which was not far from Ekbatana , at the will of Cyrus .

wealth

In addition to his defeat against Cyrus, Croesus also went down in history for his incredible wealth . The Lydian king drew his treasures from the natural abundance of raw materials in Asia Minor, especially the gold extracted from the Paktolos River and in the mines between Atarneus and Pergamon . The tribute payments of the conquered Greek cities and the tax payments from trade and economy represented a further source of income. Although Croesus was relatively rich in terms of the number of his subjects, his fortune was not nearly comparable to that of the Persian kings. The legend of his immeasurable wealth can rather be traced back to the Lydian invention of minted money , which probably took place under the reign of his father Alyattes II. Distributed throughout the world known at the time, the electron coins with his seal, a bull and a lion, gave the impression of great wealth. These gold coins were named Kroiseios after the Lydian king . The splendid palace of Croesus in Sardis was well known; it was used by the residents of the capital as a retirement home and meeting place for the gerusia .

Oracle inquiries

Croesus tried to find out with detective acumen which of the most famous oracle sites of the time could best prophesy. For this purpose he sent messengers to Abai , Delphi, Dodona and Amphiaraos , but also to the non-Greek oracle of Ammon in North Africa. Croesus had instructed his emissaries to ask exactly on the hundredth day after their departure what he, the Lydian king, was busy with. Only the Pythia at Delphi could give the correct answer that Croesus was preparing a turtle and lamb in an iron cauldron. The oracle of Amphiaraos, which Herodotus did not know, also seems to have satisfied Croesus; the other sayings were evidently entirely wrong. The reason for this test is said to have been that Croesus intended to ask the oracle that was supposed to prove itself about its prospects for a victory in a military confrontation against the rising Persian Empire. After he had sent rich gifts, he asked Delphi and Amphiaraos to inquire about them. Both oracles are said to have given the same prophecies. In addition to the already mentioned, well-known saying that if he crossed the Halys he would destroy “a great empire”, when asked whether he should find an ally, Croesus received the answer about the friendship of the most powerful of the Greek To woo peoples. While the latter replica represented cheap wisdom on a superfluous question, the first statement was already regarded as a prime example of misleading ambiguity in ancient times.

Two further oracle inquiries by Croesus are described in somewhat more detail by Herodotus. In one case he wanted to know from the Delphic Pythia whether he would sit on the throne as ruler for a long time. She allegedly replied that if a mule ever became king of the Medes, he should flee to the stony Hermos and not fear the charge of cowardice. What was meant by the mule, which Croesus could not have suspected, was none other than Cyrus II, who at that time was already the (Median and) Persian ruler. According to Herodotus, Cyrus emerged from the marriage of the Median king's daughter Mandane and the Persian Cambyses , who was hierarchically below her .

The third questioning of the Delphic Oracle mentioned by Herodotus referred to the muteness of Croesus' son. Pythia is said to have replied that his son would not speak until his most unhappy day. This prophecy is also said to have come true when ( see above ) a Persian soldier rushed to kill Croesus after taking the Lydian capital. At that time, his son allegedly saved his life by pleading not to kill his father.

When Croesus got into Persian captivity, but was finally brought back down from his pyre, he allegedly asked Cyrus to be allowed to send his shackles to Delphi to give the god worshiped there because of his misleading prophecies, which first brought him into the hands of the Persians would have to blame. But the Pythia defended their god by arguing that the fifth descendant of Gyges was destined to atone for his master's murder; But this descendant was Croesus, and no one could escape his fate. After all, the Delphic god was able to postpone the conquest of Sardis for another three years. Pythia also asserted that Croesus had misunderstood the sense of the prophecies proclaimed by the oracle. With this line of argument the ex-king is said to have been convinced that he and not the Delphic god was wrong.

Xenophon also reports on inquiries from Croesus to the oracle at Delphi. When Cyrus asked for information about this, according to Xenophon, Croesus immediately confessed that he was solely to blame for his misfortune. For first of all, through an absurd test - this is obviously alluding to the oracle question mentioned by Herodotus about the preparation of lamb and turtle meat - he incurred the wrath of the god, so that he did not answer any more questions. Through expensive offerings, he then won the oracle's goodwill again, which had given him true prophecies, such as that he would have offspring. However, one son named Atys died at a young age and the other could not speak. Sadly, he wanted to know from the oracle how he could still lead a happy life. He considered the answer that he had to recognize himself first to be easily achievable, but all of his further actions were unhappy because he had not had the required self-knowledge all the time, but had only now acquired it.

Even if the reports by Herodotus and Xenophon seem rather novel-like, it should be true in essence that Croesus often consulted oracles. According to the marble Parium, he sent in 555/554 BC. Envoys to Delphi, and according to Eusebius of Caesarea he tested 550/549 BC. The oracles. Because, according to Herodotus, a golden lion donated by Croesus as a consecration gift was damaged in the fire of the temple at Delphi (548 BC) and was therefore re-erected at a different location, the Lydian king must in any case before 548 BC. Started with his questions to Pythia.

Croesus and Solon: The Motive of Hubris

Herodotus' account of an alleged conversation between Croesus and Solon on the occasion of the sage's stay with the Lydian king is an anecdotal exaggeration.

In this story, Croesus is described as a vain ruler who respectfully welcomes and entertains his simple guest, but then leads him through his splendid treasury and asks him who he thinks is the happiest person after his extensive travels. He secretly expects his name to be dropped. But the wise man leads Tellos , whose life story he briefly touches up until his heroic death for Athens . Croesus asks further and hopes to be named at least now. But Solon next names the brothers Kleobis and Biton , who, as the priestess of Hera , would have pulled their mother's heavy processional float to the temple with their own physical strength so that she could have opened the festival for the goddess in good time, and who - at the request of the Mother to Hera to reward her children for having slept gloriously that same night . Now Croesus asks his guest if he doesn't even consider his own happiness to be equal to that of these simple people. Solon explains that fate (the Tyche ) is capricious and that he can only call the king happy when he has decided his life that way. It is necessary to wait for the end, since many people were first fortunate and ultimately ruined. But Croesus thinks him foolish and dismisses him indignantly.

The tragedy of the Lydian king presented by Herodotus in the following is to be understood - according to his remarks put in his mouth - as a retribution ( nemesis ) for his hubris . Because of his character flaws - vanity and delusion - he believes that his wealth and rule alone made him happy and does not understand Solon's warnings. Then he is hit by numerous strokes of fate and, due to his blindness, also misinterprets the saying of Pythia, so that he is led to the fateful campaign against Cyrus. Only when he faces death by fire does Solon's warning return to his memory and his exclamation “O Solon, Solon!” Together with the report of his warning brings about his rescue. In future he will act himself as a wise advisor to the Persian king.

In the oldest sources - Bakchylides and Pindar - Croesus was portrayed even more positively as a pious monarch who, after his overthrow, wanted to die a heroic death by self-immolation. Probably a pre-Herodoteic Kroisos tragedy had already occurred since the beginning of the 5th century BC. Given.

Plutarch reports that some people did not believe that the meeting between Croesus and Solon actually took place; but he himself, like most ancient authors, considered it historical. He changed Herodotus account a little and added the figure of the Greek fable poet Aisopus (Aesop) without obscuring the original story.

Herodotus already reported that not only Solon but also other members of the Seven Wise Men were in contact with Croesus, who cites the bias of Priene or Pittakos of Mytilene and Thales of Miletus by name; In fact, all the Greek sages living at the time had traveled to Sardis on various occasions. According to Diodorus, in addition to Solon, Anacharsis , Bias and Pittakos also stayed at the court of Croesus ; they were all greatly respected by the Lydian king. But since Croesus appeared vain and richly rewarded flatterers, but the wise men answered his questions honestly and objectively, without praise, he was deeply disappointed in them. The Lydian king is said to have promised a golden phial as a price for an agon of the Seven Wise Men . Also cited are three letters allegedly from Solon, Pittakos and Anacharsis addressed to Croesus, all of which are of course inauthentic.

metaphor

In German colloquial language, a rich person living in luxury is referred to as Croesus based on the historical model ; hence the phrase “Am I Croesus?”, with which financial claims are to be warded off.

Artistic implementations

Reinhard Keizer brought out an opera in 1710 with the title The haughty, fallen and again sublime Croesus in the opera on Gänsemarkt in Hamburg ; Gotthold Ephraim Lessing discussed them in his Hamburg Dramaturgy .

In 1779, the opera Creso in Media by Mozart's contemporary Joseph Schuster (1748–1812) premiered in Naples . The action takes place during a campaign that Croesus wages against the Persians in the media.

literature

- Annemarie Ambühl : Kroisos. In: Peter von Möllendorff , Annette Simonis, Linda Simonis (ed.): Historical figures of antiquity. Reception in literature, art and music (= Der Neue Pauly . Supplements. Volume 8). Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2013, ISBN 978-3-476-02468-8 , Sp. 589-594.

- Peter Högemann , Christiane Schmidt: Kroisos. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 6, Metzler, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-476-01476-2 , Sp. 858-860.

- Rudolf Schubert : History of the kings of Lydia. Koebner, Breslau 1884.

- Franz Heinrich Weißbach : Kroisos. In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Supplementary volume V, Stuttgart 1931, Col. 455-472.

Web links

- Myths from Anatolia

- Jona Lendering: Croesus . In: Livius.org (English)

Remarks

- ↑ Katrin Euler, David Sasseville: The identity of the Lydian Qλdãns and its cultural-historical consequences , in: Kadmos , 2019, No. 58, pp. 125–156.

- ↑ In terms of its genre, this text is not so much written as a historiography , but rather as an instruction based on history ( see also: Fürstenspiegel , Politische Bildung ).

- ^ Franz Heinrich Weißbach : Kroisos. In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Supplementary volume V, Stuttgart 1931, Sp. 455–472, here: 456. Peter Högemann , Christiane Schmidt: Kroisos. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 6, Metzler, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-476-01476-2 , Sp. 858-860, here: 859.

- ↑ Herodotus , Historien 1, 92; Nikolaos of Damascus in Felix Jacoby , The Fragments of the Greek Historians (FGrH), No. 90, F 65; Plutarch , de Pythiae orac. 16.

- ↑ Aristotle in Stephanos of Byzantium , Ethnika and Johannes Lydos , De mensibus 4, 18.

- ↑ Herodotus, Historien 1, 73f .; Aelianus , Varia historia 3, 26.

- ↑ Herodotus, Historien 1, 34; 1.85; Cicero , de divinatione 1, 121; Pliny , Natural History 11, 270; u. a.

- ↑ Xenophon , Education of Cyrus 7, 2, 26.

- ↑ Herodotus, Historien 1, 26; 1.86; 3, 34.

- ↑ Eusebius of Caesarea , Chronicle , pp. 32f., 151 and 188f. ed. Karst.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the life and teachings of famous philosophers , I 38; Hieronymus, Chronik , I 102f., II 203 and 299 ed. Helm; Solinus, collectanea rerum memorabilium 1, 112.

- ↑ This reading forms the new basis for all future evaluations in Robert Rollinger : The Median Empire, the End of Urartu and Cyrus the Great Campaigne 547 BC. Chr. In Nabonaid Chronicle II 16 in: Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Ancient Cultural Relations between Iran and West-Asia , Teheran 2004, pp. 5-6.

- ↑ a b Nikolaos of Damascus, FGrH 90, F 65.

- ↑ a b Herodotus, Historien 1, 92.

- ↑ Plutarch, de Pythiae orac. 16.

- ↑ Herodotus, Historien 1, 51; Plutarch, de Pythiae orac. 16.

- ^ Lydian Period. (900-547 BCE.). (No longer available online.) Thracian Ltd, April 3, 2011, archived from the original on August 25, 2011 ; accessed on August 22, 2011 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ gates Kjeilen: Lydia. (No longer available online.) LookLex Encyclopaedia, archived from the original on August 29, 2011 ; accessed on August 22, 2011 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Herodotus, Historien 1, 26; Polyainos , Strategika 6, 50; Aelianus, varia historia 3, 26.

- ↑ Herodotus, Historien 1, 27; Polyainos, Strategika 1, 26.

- ↑ Herodotus, Histories 1, 28.

- ↑ Herodotus, Historien 1, 28; Strabon , Geographika 12, 1, 3.

- ↑ Herodotus, Historien 1, 76; Strabo, Geographika 13, 1, 42.

- ↑ Strabo, Geographika 13, 1, 11; 13, 1, 42.

- ↑ Herodotus, Historien 6, 37

- ↑ Herodotus, Histories 1, 6; 1, 27.

- ↑ Herodotus, Histories 1, 22; 1, 141.

- ↑ Strabo, Geographika 13, 1, 25; 14, 1, 21. The relocation of settlements to escape positions in the mountains was to be found throughout antiquity when there was a danger of pirates, as was the return to the vicinity of the cultivation areas if this threat no longer existed.

- ↑ Herodotus, Historien 1, 46; 1.73; 1, 75

- ↑ Herodotus, Histories 1, 6; 1.69; 1, 77.

- ^ Herodotus, Histories 1, 71.

- ↑ Herodotus, Historien 1, 75-76.

- ↑ Herodotus, Historien 1, 76; 1, 141; Diogenes Laertios , On the Lives and Teachings of Famous Philosophers 1, 25.

- ^ Diodorus, Libraries 9, 31, 4.

- ↑ Herodotus, Histories 1, 76-77.

- ↑ Herodotus, Historien 1, 79-81.

- ^ Herodotus, Histories 1, 84.

- ↑ a b Xenophon, Education of Cyrus 7, 2.

- ↑ Ktesias, Persica , fragment 23.

- ↑ Eusebius of Caesarea, Chronicle , p. 33 ed. Karst.

- ↑ Bakchylides 3: 23-62.

- ↑ Herodotus, Historien 1, 85-91; then Diodor, Libraries 9, 34; Plutarch, Solon 28.

- ↑ Nikolaos of Damascus, FGrH 90, F 68.

- ↑ Ktesias, Persika , fragment 23.

- ↑ Herodotus, Historien 1, 153; 1: 155-156.

- ↑ Herodotus, Historien 1, 207-208.

- ↑ Herodotus, Histories 3:14.

- ↑ Herodotus, Historien 3, 34; 3, 36.

- ↑ Herodotus, Histories 1, 30 and 32 and many other sources.

- ↑ Strabo, Geographika 13, 4, 5; 14, 5, 28; u. a.

- ↑ Vitruv , Ten Books on Architecture 2, 9; Pliny, Natural History 35, 172.

- ↑ Herodotus, Histories 1, 46-49.

- ↑ Herodotus, Histories 1, 53.

- ↑ Aristotle, rhetorica 3, 5, 4; Cicero, de divinatione 2, 115; u. a.

- ^ Herodotus, Histories 1, 55.

- ↑ Herodotus, Histories 1, 85.

- ↑ Herodotus, Historien 1, 90-91.

- ↑ Xenophon, Education of Cyrus 7, 2, 15 ff.

- ↑ Herodotus, Historien 1, 50.

- ^ FH Weissbach: Kroisos . In: RE, Supplement 5, Col. 470.

- ↑ Herodotus, Historien 1, 29-33.

- ^ Franz Heinrich Weißbach: Kroisos. In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Supplement volume V, Stuttgart 1931, Sp. 455-472, here: 471. Peter Högemann, Christiane Schmidt: Kroisos. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 6, Metzler, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-476-01476-2 , Sp. 858-860, here: 859.

- ^ Plutarch, Solon 27-28.

- ↑ Herodotus, Historien 1, 27; 1.29; 1, 75.

- ^ Diodor, Libraries 9, 26-28.

- ↑ Plutarch, Solon 4, 7; Diogenes Laertios, On the Lives and Teachings of Famous Philosophers 1.30.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Lives and Teachings of Famous Philosophers 1:67; 1.81; 1, 105.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Alyattes II. |

King of Lydia 555-541 BC Chr. |

- |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Croesus |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Kroisos; Croesus |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | last king of Lydia |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 590 BC Chr. |

| DATE OF DEATH | around 541 BC Chr. |

| Place of death | Sardis |