wealth

Wealth describes the abundance of tangible or spiritual values. However, there is no generally applicable definition, as the idea of wealth depends on culturally shaped, subjective and sometimes highly emotional or normative values . In modern industrialized countries , wealth is often only quantitatively related to prosperity and standard of living , although it can not in fact be reduced to material goods. The importance of intellectual wealth is often underestimated, partly because it is difficult to measure. Socially speaking, the creation of wealth requires the generally accepted understanding that things, land or money belong to someone and that that property be protected. Wealth is (or was) unknown in egalitarian societies . The cultural diversity of the term is in part the subject of heated debates .

The opposite of material wealth or economic wealth - that is, the lack of goods or an above-average low quantitative prosperity - is called poverty ; here too there is a distinction between material and spiritual poverty.

etymology

The corresponding adjective for “wealth” is rich . It can also be found in other Germanic languages, e.g. B. in English rich or in Swedish rik . In its historically oldest form, got. Reiks , the adjective means “mighty” and the noun “ruler, authority”. Linguists ultimately assume a Celtic origin.

Material and monetary wealth

According to calculations by Oxfam from 2014, the richest 85 people have the same wealth as the poorer half of the world's population combined. These 85 richest people, according to the report, have a fortune of £ 1 trillion, the equivalent of the 3.5 billion poorest people. The wealth of the richest percent of the world's population continues to total £ 60.88 trillion.

Psychological effects

Immoral behavior

A person's prosperity influences how they think, act and feel. According to psychological research, wealthy people tend to only help others in need if this is done publicly or if they can pose as benefactors. In addition, the rich are more likely to lie and cheat than people of lower socio-economic rank. Wealth also decreases empathy . The same behavior is evident not only in field studies , but also can be produced in experimental laboratory studies by a higher socio-economic status in the study participants feeling induced .

Limited impact on wellbeing

In general, money is relevant for well-being , but the effect is usually overestimated. In addition , high income, in particular, only has a limited (in the literal sense) influence on happiness in life , since above a certain level of income the indicators for happiness in question reach a limit or " saturation ", i. H. a plateau from which they no longer rise. For Western Europe and Scandinavia, this plateau is reached from a weighted equivalent annual income of 50,000 to 100,000 dollars (depending on the indicator). The latter value (in the year the study was published) corresponded to an income of 7,062 euros per month. From the point of view of the study authors, the study results can help governments to motivate measures to redistribute wealth. For comparison: In Germany, the maximum tax rate applied in 2019 from a taxable monthly income of 22,111 euros for individual assessments.

Economic Effects

When massive portions of a nation's income are concentrated in the hands of a few, overall economic growth suffers . A 2015 study by the International Monetary Fund found that "as the income share of the top 20% (the rich) increases, GDP growth actually decreases in the medium term, suggesting that profits are not trickling down, " while "a Increase in the income share of the bottom 20% (the poor) is associated with higher GDP growth. "

Wealth in Germany

Germany is - measured in terms of gross domestic product (GDP) - a very rich country in a global comparison. Between 1960 and 2003, GDP adjusted for inflation tripled. Between 1991 and 2001 it grew by almost 16% from 1,710 billion euros to 1,980 billion euros. The financial assets owned by private individuals rose by around 80% in these ten years, from € 2.0 trillion in 1991 to € 3.6 trillion in 2001.

The more money a person has, the higher they subjectively set the limit above which they consider someone rich. One-person households with a net income of more than EUR 2,700 per month no longer belong to the middle class, even if those affected often do not see it that way. They can be called "wealthy". From a net income of 3,600 euros (as of 2019), science describes a person as rich.

Wealth

As an objective indicator of prosperity and wealth is assets rather more important than income . Wealth can serve as security and compensate for temporary loss of income. In 2019, according to the global wealth report from Credit Suisse , the median wealth in Germany was 35,313 US dollars, which corresponds to around 31,500 euros. If the limit of 200% of the median proposed by Ernst-Ulrich Huster is applied, the result for Germany is wealth from assets of 63,000 euros. According to official statistics, this so-called wealth threshold in 2013 was 77,378 euros.

Wealth, especially monetary wealth, is very unevenly distributed (see wealth distribution in Germany ). While in 2003 the "lower" 50% of all households together owned 3.8% of total wealth, the "upper" 10% of households owned 46.8% of private wealth in Germany. In 1998 this ratio was 3.9% to 44.4%. This trend continued in the following years. In 2017, the poorer half of the population had 1.3% of the total wealth, the richest 10% 56%. DIW estimates, which supplemented missing data from the Federal Statistical Office (see section Income wealth), resulted in an even greater concentration of wealth. According to this, the richest 10% of Germans owned at least 63% of the national wealth.

There is a high east-west divide in the distribution of wealth . So come z. B. of the 1,000 richest Germans, only 10 families from East Germany. Looking at the total population, the average wealth of an East German is about half as high as that of a West German. However, the concentration of wealth in the new federal states seems to be greater than in the old ones.

There is also a concentration of wealth within the richest 10%. In 2008 0.001%, i.e. 380 households, owned a net wealth of 419.3 billion euros or 5.28% of the net wealth of private households. The richest 0.0001% of households (38 households) owned 132.35 billion euros or 1.67% of total private wealth.

People whose wealth is so large that they live on it without actively working are called privateers . There were around 627,000 private individuals in Germany in 2018. This corresponds to an increase of 68.5% since the turn of the millennium.

In 2010 there were still 830,000 wealthy millionaires in Germany. By 2013 that number had increased to 1,015,000. According to the World Wealth Report 2018, the number of wealthy millionaires in Germany rose further to 1.364 million millionaires.

According to the business magazine Forbes , the number of billionaires in Germany almost doubled from 55 to 107 between 2010 and 2019.

The richest Germans with the greatest wealth in 2020 were Susanne Klatten (16.44 billion euros; SKion , BMW ), Beate Heister and Karl Albrecht Jr. (29.25 billion euros; Aldi Süd ) and the Reimann family (35 billion euros ). Euro, chemical company Benckiser ).

In the international comparison

According to the Credit Suisse Global Wealth Report, the concentration of wealth in Germany is greater than in other Western European countries. The richest percent of the population in Germany has 30% of the wealth. By contrast, in Great Britain the richest percent of the population has 24% of the wealth, in Italy and France 22% each.

origin

According to Michael Hartmann , the concentration of wealth in Germany is due to the high number of family businesses and their benefits under the inheritance tax law of 2009. The beneficiaries are not, as has often been shown, larger craftsmen's businesses, but large and very large companies. In contrast to other countries in Germany, around half of the 100 largest companies are family-owned. (The general manager of the Association of Family Entrepreneurs, who was referred to in Manager Magazin as the "chief lobbyist of the rich", made a similar statement insofar as, according to him, in the case of family entrepreneurs, the business assets on the balance sheet are often indistinguishable from the assets of rich people.) An example That would be Robert Bosch GmbH, which in 2020 ranked tenth among the family businesses with the highest turnover in the world. According to the information, the group is 99% owned by the family of the company founder.

According to Hartmann, the inheritance tax law, which was hardly changed by a 2016 reform, enables large corporate assets to be inherited almost tax-free. Hartmann refers to statistics according to which the inheritance tax in companies, the higher the smaller the inherited wealth.

In the case of the richest percent of Germans, around 80% of their wealth comes from inheritances .

Social milieu

A study commissioned by HypoVereinsbank in 2009 based on a sample of people with at least one million euros showed several social milieus among wealthy people. The proportionately largest group with 20 to 25% were the "status-oriented wealthy". They were characterized by a focus on performance, an appreciation of their own abilities and a desire for recognition. It is typical that the people concerned try to impress others through status symbols and luxury consumption and to gain admiration for themselves. At the same time, they often have the feeling that they are not fully recognized by other wealthy as well as envious people. In a classification of the study by Der Spiegel , Carsten Maschmeyer was named as a representative of the status-oriented wealthy.

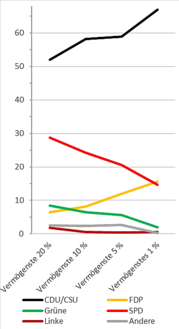

Party preferences

As wealth increases, so does party preference. With increasing wealth, the preference for the CDU and FDP increases, for all other parties it decreases.

Debt

In contrast to private wealth, the over-indebtedness of almost 2.8 million households. In 2002, household debt was € 1,535 billion, corporate debt was € 3,142 billion and public debt was € 1,523 billion (2006). The net financial assets of all companies were negative at € −1,241 billion, while that of the state was € −1,061 billion. Conversely, the net financial assets of private households and insurance companies and banks were € 2,380 billion.

Income wealth

People with more than 200% of the equivalently weighted median income live in wealthy conditions. This limit was suggested by Ernst-Ulrich Huster . In 2015, the limit was around 3,390 euros per month.

frequency

From 1991 to 2015, the share of the rich rose from 5.6 to 7.5% of the population.

This share, known as the wealth quota , is highest in the federal states of Hesse (10.6%), Bavaria (10.2%) and Baden-Württemberg (10.1%). The wealth quota is lowest in Saxony (3.2%), Saxony-Anhalt (3.0%) and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania (3.0%).

The actual wealth rates are higher because, due to data collection using voluntary self-disclosure and the willingness to provide information decreasing with increasing income and wealth, the statistically evaluable data basis for high incomes and wealth is so inadequate that the Federal Statistical Office only considers net household income up to the cut-off limit of € 18,000 / month . Around 70% of the self-employed and property income are therefore not included in the distribution calculations. Also excluded from the survey are profits not withdrawn by the self-employed and people in shared accommodation, e.g. residents of a nursing home, as well as the homeless. The size of the deviation from the actual income is shown by the comparison between the income sums of the EVS with the actual income sums of the national accounts (VGR).

In 2008, the difference between the statistical self-employed and property income of 139 billion euros in the EVS and the similar income total of 477 billion euros in the national accounts was around 338 billion euros. Around 71% of this income was not recorded by the EVS and is not shown in the distribution calculations and thus in the unequal distribution measures such as the Gini index or the wealth rate . According to the Federal Statistical Office, "this indicates a fundamental problem with the measurement of self-employed and property income in (voluntary) household surveys".

The number of income millionaires has grown from just under 12,500 in 2009 to over 21,000 in 2015.

Assumed vs. actual income wealth

According to a survey conducted by the Humboldt University in Berlin on behalf of the Geo magazine in 2007, the respondents assumed that the average salaries of CEOs in 2006 were € 125,000 per month. However, the monthly income of the CEOs of the DAX stock corporations in 2006 was € 358,000. In 2007 they rose to € 374,000 and € 391,000 respectively.

Association of Taxpayers

According to observers, the taxpayers' association, contrary to its name, does not represent the interests of all taxpayers, but only those of the rich. Observers came to this conclusion, among other things, because 22% of the readers of the members' magazine have a net household income of more than 5,000 euros per month (in the general population: 8%). SPD representatives also expressed the view that the association primarily conducts interest politics for the wealthy and the wealthy.

Party preferences

In Germany, voters with different party preferences have different mean net household incomes. In the 2017 federal election year, according to DIW, the three parties whose potential voters included the highest household incomes were CDU and Alliance 90 / Greens with € 3,000 each and FDP with € 3,400. For comparison: the wealth limit for income in 2015 was around € 3,390.

"Wealth tax"

The number of those affected by the tax on the wealthy is considerably lower than that of the wealth quota, since "the rich" is only used here as a catchphrase for a subgroup and not in a scientific sense. In 2009, people affected by the tax on the rich had an income of more than 250,401 euros for individual assessments and 500,802 euros for joint assessments. In 2009 this number totaled around 57,942 people, i.e. 0.22% of taxpayers. This number rose to around 156,000 taxpayers by 2017 and to around 163,000 by 2018 (with over € 256,304 individual taxation and € 512,608 joint taxation).

Tax audits

On the other hand, according to information from the Federal Ministry of Finance, the number of company audits by tax auditors is declining for people with an income of over 500,000 euros per year. It fell by almost 30% from 1,630 in 2009 to 1,150 in 2018.

Influence in political decisions

According to a research report from 2016 on behalf of the Federal Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs , the preferences of social groups are taken into account to varying degrees in political decisions in Germany. Data from the period between 1998 and 2015 were evaluated. There is a clear correlation between decisions on the attitudes of people with higher incomes, but none or even a negative correlation for those with low incomes.

causes

The causes of high incomes are to be distinguished from those of low incomes. While low incomes have mainly been caused by characteristics of the labor market since reunification, the decisive factor for high incomes were “the sharply increased contribution assessment ceilings for social insurance, which are increasingly burdening households with average or slightly above-average wages. The peculiarities of the German social security system, combined with increased wage inequality since reunification, have led to a huge redistribution from middle to higher incomes. "

Wealth in Austria

(Compare: Distribution of wealth in Austria )

In 2001 private assets in Austria amounted to around € 581 billion. The richest individual living in Austria was (died on October 5, 2006) with € 5.4 billion Friedrich Karl Flick . The richest native Austrian is Dietrich Mateschitz . In addition to them, there are 350 people in Austria who can count over € 10.9 billion in their property and around 28,000 millionaires.

Top earners can be found in Austria in the private sector , art or professionally conducted sport . With an annual gross income of approx. € 10 million, Siegfried Wolf, CEO of Magna- Austria, can be identified as the best earner .

The statistically average Austrian earns around € 18,750 after taxes per year and the statistically average Austrian around € 12,270 after taxes per year. These are values for employed persons without apprentices from 2003.

Millionairs for Humanity

On the occasion of the Corona crisis, 83 millionaires from seven countries who called themselves "Millionairs for Humanity" demanded in an open letter to governments worldwide that Oxfam and other aid organizations should raise permanently higher taxes for the richest. The undersigned see this as a way to adequately finance health systems, schools and social security. They appealed, "Tax us. Tax us. Tax us. It's the right choice. It's the only choice."

Different perspectives

“The love of property is like a disease with them (the whites). These people have made many commandments that the rich can break but the poor cannot. They levy taxes on the poor and the weak to feed the rich and rulers. (...) "

The social science view of wealth

The anthropology and sociology describe societies about their understanding of wealth and on the structures and instruments of power , who use them to protect this wealth. Moreover, the wealth of prestige- conferring goods can be examined anthropologically as the cause of fetishism . Among other things, there are grotesque cases in which people were sexually aroused by their account balance or the money on it ( paraphilia ).

In addition, social science observes the accumulation of wealth under the aspect of the distribution of resources and thus also the distribution of power. Modern elite sociology , particularly power structure research , view the development of wealth very critically.

Criticism of wealth

The ancient philosopher Plato wrote an extensive work on the connections between wealth, one-sided concentration of power and moral decline. Historians often consider the enormous wealth of Rome to be the cause of the decline in Roman society in the 1st century BC. Seen. Today the exclusively material concept of wealth is often criticized: People who enjoy a high standard of living would easily lose their “spiritual vigilance” and their “social wealth”.

Friedrich Nietzsche believes that wealth creates an aristocratic race because it allows the most beautiful women to be chosen, the best teachers to be paid, sport to be played and dull physical work to be avoided. These effects would arise even with little wealth, there would be no increase, even if the wealth is increased considerably. Poverty is only useful for those who seek their happiness in the splendor of the courtyards, as helpers for the influential or as church leaders.

The social psychologist Erich Fromm provided a very detailed discussion of the causes of today's concept of wealth with his work, haben oder sein , published in 1976 . He sees Western culture as a breeding ground for the existence of the “eternal baby who cries for the bottle”, instead of an attitude that deals productively with the world and gives little to material possessions.

The critics of the rich are z. Sometimes it is assumed that they are not concerned with justice, but that they are driven by envy . However, this accusation is criticized as being unconvincing, since feelings of envy presuppose a social closeness , which can hardly arise, since the super-rich live in a kind of parallel world through isolation. The envy allegation should therefore rather be an immunization strategy . Envy, on the other hand, is directed much more often towards poorer people - e.g. B. Refugees and welfare recipients - who receive government support.

The view of worldviews

In the original Christian faith, Jesus Christ preached : "A camel is more likely to come through the eye of a needle than a rich man into heaven". In the Gospel of Mark he wanted to show that one should not rely on one's wealth when it comes to “inheriting eternal life” (Mk 10:17 b). Among other things, most Christians believe that wealth does not put one person above others. Of course, wealth is not declared as negative per se . Christ's word is to be seen more in the historical context, insofar as wealth in Jesus' time could only stand on moral feet, namely exploitation and oppression. In this context, wealth is also to be understood as a symbol of excessive attachment to the earthly. The connotation of a rich man with a lack of morality and a lack of focus on God is thus denounced here. Rather, the rich have an obligation to help the poor.

Based on the determination / predestination thinking of Luther and Calvin, the Protestant mentality connoted wealth as an indication of the election of the rich by God ( Calvinism ). The rich man therefore “earned” his wealth in the highest sense. This thinking has had socio-cultural effects to this day in the core countries of Protestantism such as Great Britain and the USA. In connection with wealth, Protestant states traditionally use the term performance justice more often than the term distributive justice that is common in Catholicism .

With regard to Buddhism , being wealthy is viewed as a burden, similar to early Christianity . Tenzin Gyatso, the current Dalai Lama , says: “The satisfaction of having money in the bank may make you happy at the moment, but as time goes on, the one who owns it is more and more afraid that he could lose everything. The great teacher ( Buddha ) preached poverty because he saw it as a kind of 'salvation'. "

The representatives of indigenous peoples also often turn against the Eurocentric ideas of wealth and progress. Often times, material possessions go against their traditional beliefs and spiritual beliefs.

literature

- Hans Herbert von Arnim : The European plot. How EU officials sell our democracy . Munich 2006, ISBN 978-3-446-20726-4

- Hans-Georg Bensch: On the wealth of societies . Critical Studies 9, Lüneburg 1995

- Volker Berghahn u. a. (Ed.): The German business elite in the 20th century . Essen 2003

- Daniel Brenner: Boundless wealth. Perception, Representation and Significance of Billionaires . University and State Library Münster , Münster 2018, ISBN 978-3-8405-0182-1 .

- Zdzislaw Burda u. a .: Wealth condensation in Pareto macroeconomies . In: Physical Review E, Vol. 65, 2002

- Federal Ministry for Labor and Social Order (2001) (Hrsg.): Lebenslagen in Deutschland. The federal government's first poverty and wealth report . Bonn

- Jared Diamond : rich and poor. The fates of human societies . Frankfurt / M. 2006, ISBN 978-3-596-17214-6

- Thomas Druyen: Gold Children. The world of wealth . Hamburg 2007, ISBN 978-3-938017-85-2

- Wealth and fortune. On the social significance of wealth and wealth research , Wiesbaden 2009 ( in the Google book search )

- Christoph Deutschmann (1999): The promise of absolute wealth. On the religious nature of capitalism . Frankfurt / M. / New York, ISBN 978-3-593-36253-3

- Robert H. Frank : Richistan: A Journey Through the American Wealth Boom and the Lives of the New Rich . 2007

- Chrystia Freeland : The Super Rich . Rise and rule of a new global money elite. Westend, Frankfurt 2013, ISBN 978-3-86489-045-1 .

- Eva Maria Gajek; Anne Kurr; Lu Seegers (Ed.): Wealth in Germany. Actors, networks and lifeworlds in the 20th century, Göttingen . Wallstein Verlag, 2019, ISBN 978-3-8353-3409-0 .

- Dennis Gastmann: Closed society. A wealth report . Rowohlt Verlag, Berlin, August 2014. ISBN 978-3-87134-773-3 .

- Walter Hanesch, Peter Krause, Gerhard Bäcker a. a .: Poverty and wealth in Germany. The new poverty report from the Hans Böckler Foundation, the DGB and the Paritätischer Wohlfahrtsverband . Reinbek 2000

- Ulrike Herrmann , The Victory of Capital. How Wealth Came into the World: The Story of Growth, Money and Crises . Westend Publishing House. Frankfurt am Main. 2013. ISBN 978-3-86489-044-4

-

Jörg Huffschmid :

- The politics of capital . 4th edition, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt 1971

- Who owns Europe? 2 vol., Heilbronn 1994

- Michael Jungblut : The rich and the super-rich in Germany. Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 1971, ISBN 978-3-455-03690-9

- Dieter Klein : Billionaires - empty funds. The mysterious whereabouts of the rising wealth . Berlin 2006, ISBN 978-3-320-02081-1

- Hans-Jürgen Krysmanski : 0.1% - The billionaires ' empire , Westend 2012

- F. Lundberg: The rich and the super rich. Power and omnipotence of money . Hamburg 1969

- Loretta Napoleoni : Modern Jihad. Tracing the Dollars Behind the Terror Networks . London 2003

-

Christian Neuhäuser :

- Wealth as a moral problem . Suhrkamp 2018, ISBN 978-3518298497

- How rich can you be? About greed, envy and justice . Reclam 2019, ISBN 978-3150196021

- Kevin Phillips: The American Money Aristocracy . Frankfurt / M. / New York 2003

- Birger Priddat : "Why be rich? Assets, foundations, the state - The basic patterns of legitimate wealth", 111 - 116 in: Lettre International No. 98, autumn 2012

- Thorstein Veblen : Theory of the Fine People . Frankfurt / M. 1997, ISBN 978-3-596-17625-0

- Ulrich Viehöver : The Influences. Henkel, Otto and Co - Whoever has money and power in Germany . Frankfurt / M. 2006, ISBN 978-3-593-37667-7

- Georg Wailand : From bar pianist to Billa owner. In: The rich and the super-rich in Austria. Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 1982, ISBN 3-455-08948-8 , pp. 168-170.

- Wolfgang Zapf : Changes in the German elite . Munich 1966.

Web links

- Federal Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs : armuts-und-reichumsbericht.de

- "World Wealth Report", June 2008. ( Memento from May 29, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 7 kB) Merrill Lynch (statistics on the people with the largest net wealth in the world)

- Focus.de , Focus Magazin 31/2007, Kerstin Holzer: The worries are shifting (The sociologist Thomas Druyen on the attitude to life and responsibility of the super-rich)

- presseportal.de: BILANZ determines 150 billion assets in Germany

- Statistics Austria , statistik.at: gross and net annual income of employed persons 1997 to 2017 (Austria)

- visualcapitalist.com December 26, 2018, Nick Routley: Visualizing the Extreme Concentration of Global Wealth (" Visualizing the Extreme Concentration of Global Wealth ")

- Zeit.de , Die Zeit 52/2006, Stephan Lebert , Stefan Willeke : The Starnberg Republic . In: Die Zeit , No. (Nowhere in Germany do more millionaires live than on Lake Starnberg. The state, that's them - the mayor also fears their lawyers. Visiting the upper class who lives as they please)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Wolfgang Pfeifer: Etymological dictionary of German: Lemma rich

- ↑ DWB: rich

- ↑ The Guardian, Oxfam: 85 richest people as wealthy as poorest half of the world , Jan. 20, 2014

- ^ The Independent, World's 85 richest people have as much as poorest 3.5 billion: Oxfam warns Davos of 'pernicious impact' of the widening wealth gap , January 20, 2014

- ↑ Researchers prove: money spoils character. In: Frankfurter Rundschau. February 28, 2012, accessed September 17, 2019 .

- ↑ Daisy Grewal: How Wealth Reduces Compassion. In: Scientific American . Retrieved September 12, 2019 .

- ↑ Maia Szalavitz: The Rich Are Different: More Money, Less Empathy . In: Time . ISSN 0040-781X ( online [accessed September 17, 2019]).

- ↑ PK Piff, DM Stancato, S. Cote, R. Mendoza-Denton, D. Keltner: Higher social class predicts increased unethical behavior . In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences . tape 109 , no. 11 , March 13, 2012, ISSN 0027-8424 , p. 4086–4091 , doi : 10.1073 / pnas.1118373109 , PMID 22371585 , PMC 3306667 (free full text) - ( online (PDF) [accessed September 17, 2019]).

- ↑ Lara B. Aknin, Michael I. Norton, Elizabeth W. Dunn: From wealth to well-being? Money matters, but less than people think . In: The Journal of Positive Psychology . tape 4 , no. 6 , November 2009, ISSN 1743-9760 , p. 523-527 , doi : 10.1080 / 17439760903271421 .

- ↑ Andrew T. Jebb, Louis Tay, Ed Diener, Shigehiro Oishi: Happiness, income satiation and turning points around the world . In: Nature Human Behavior . tape 2 , no. 1 , 2018, ISSN 2397-3374 , p. 33–38 , doi : 10.1038 / s41562-017-0277-0 ( online [accessed September 17, 2019]).

- ↑ § 32a EStG - single standard. Retrieved July 7, 2020 .

- ↑ Era Dabla-Norris, Kalpana Kochhar, Nujin Suphaphiphat, Frantisek Ricka, Evridiki Tsounta: Causes and Consequences of Income Inequality: A Global Perspective . Ed .: International Monetary Fund. June 2015 ( online (PDF) ): “if the income share of the top 20% (the rich) increases, then GDP growth actually declines over the medium term, suggesting that the benefits do not trickle down” [while] “an increase in the income share of the bottom 20% (the poor) is associated with higher GDP growth. "

- ↑ Larry Elliott Economics editor: Pay low-income families more to boost economic growth, says IMF. In: The Guardian. June 15, 2015, accessed May 27, 2020 .

- ↑ Tobias Kaiser: Income distribution: IMF warns of inequality and poverty. In: The world. June 15, 2015, accessed May 27, 2020 .

- ↑ MACROFINANCE LAB BONN. Retrieved June 10, 2020 (American English).

- ↑ Hendrik Ankenbrand, Patrick Bernau: Poor upper class: This is how the richest percent of Germans live. In: FAZ.NET. Retrieved July 22, 2018 .

- ↑ Psychology and Privilege - The Unpleasant Truth of Social Injustice. In: Deutschlandfunk Kultur. Deutschlandradio, accessed on July 19, 2019 .

- ↑ Anthony Shorrocks, Jim Davies, Rodrigo Lluberas: Global wealth report 2019 . In: Credit Suisse Research Institute (ed.): Global wealth reports . October 2019 (English, online (PDF) ).

- ^ State capital Munich (ed.): Münchner Armutsbericht . Munich 2017 ( online [PDF]).

- ↑ Jürgen Faik, Ernst Kistler: Short study on the current development of poverty and social inequality in Rhineland-Palatinate . Stadtbergen / Frankfurt am Main September 2016 ( online (PDF) ).

- ↑ Wealth and finances of private households in Germany: results of the 2017 wealth survey . In: Deutsche Bundesbank (Ed.): Monthly report . ( online (PDF) ).

- ↑ Everyone is in the middle. In: The time. Retrieved June 22, 2020 .

- ↑ Holger Zschäpitz: Bundesbank study: The fortunes reveal Germany's problems. In: The world. April 15, 2019, accessed June 22, 2020 .

- ↑ Life situations in Germany . ( Memento of the original from March 28, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF) The Federal Government's 2nd Poverty and Wealth Report . P. 24. Draft (version for departmental coordination and participation of associations and science). December 14, 2004

- ↑ New study on wealth distribution: Always more for a few. In: The daily newspaper. October 2, 2019, accessed May 11, 2020 .

- ↑ Ulrike Herrmann: The fortune of millionaires: Hidden wealth. In: The daily newspaper. December 18, 2019, accessed May 11, 2020 .

- ↑ a b Anne Kunz: Millionaires: Why the rich upper class is missing in the East . In: THE WORLD . December 26, 2019 ( welt.de [accessed August 11, 2020]).

- ↑ Joachim R. Frick, Markus M. Grabka, Richard Hauser: The distribution of wealth in Germany - empirical analyzes for people and households . Berlin 2010, p. 56. Numbers there according to Klaus Boldt: The 300 richest Germans . In: Manager Magazin Spezial , October 2008, pp. 12–57. and after: Wojciech Kopczuk , Emmanuel Saez : Top Wealth Shares in the United States: 1916-2000: Evidence from Estate Tax Returns . (PDF; 1.0 MB), in: National Tax Journal , 2004, 57, pp. 445–488.

- ^ Edward N. Woolf: The Asset Price Meltdown and the Wealth of the Middle Class . (PDF; 220 kB) New York University, 2012, p. 58.

- ↑ Martin Greive: Fortune: The number of privateers in Germany is increasing rapidly. In: Handelsblatt. September 1, 2019, accessed September 3, 2019 .

- ↑ Assets in Germany: The number of privateers is increasing rapidly. In: Spiegel Online. September 2, 2019, accessed September 3, 2019 .

- ↑ Valluga Ag asset report, data published from www.dasinvestment.com/.

- ↑ focus.de - There are more than a million millionaires living in Germany , accessed on September 3, 2013

- ↑ World Wealth Report 2018: Total Millionaires Wealth Over $ 70Bil USD. In: Capgemini Germany. June 19, 2018, accessed March 1, 2020 .

- ↑ Nina Jerzy: Countries with the most new billionaires. In: Capital.de. May 17, 2020, accessed May 19, 2020 .

- ↑ Andreas Bornefeld, Christoph Neßhöver, manager magazin: Richest Germans: The 1001 greatest fortunes 2019 - manager magazin - Politik. Retrieved July 6, 2020 .

- ↑ The richest Germans 2020 | The current list of billionaires. January 1, 2020, accessed on July 6, 2020 (German).

- ↑ Anthony Shorrocks, Jim Davies, Rodrigo Lluberas: Global wealth report 2019 . In: Credit Suisse Research Institute (ed.): Global wealth reports . October 2019, p. 48 (English, (PDF) - "Wealth inequality is higher in Germany than in other major West European nations… We estimate the share of the top 1% of adults in total wealth to be 30%, which is also high compared with Italy and France, where it is 22% in both cases. As a further comparison, the United Kingdom ['s]… share of the top 1% is 24%. ").

- ↑ Kristina Antonia Schäfer: Global Wealth Report 2019: The Prosperity Illusion. Retrieved January 5, 2020 .

- ↑ a b Lea Fauth: Elite researcher on wealth: “Billions inherited tax-free” . In: The daily newspaper: taz . July 16, 2020, ISSN 0931-9085 ( taz.de [accessed July 28, 2020]).

- ↑ Lukas Heiny, manager magazin: Wealth tax: How the rich influence politics - manager magazin - companies. Retrieved July 28, 2020 .

- ↑ The largest family businesses in the world. August 15, 2020, accessed on August 24, 2020 (German).

- ↑ Timm Bönke, Giacomo Corneo, Christian Westermeier: Inheritance and personal contribution in the assets of the Germans: A distribution analysis, April 2015 . ( Memento from April 19, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF) p. 30 u. 34

- ↑ Christian Rickens, manager magazin: Upper-class milieus: Expedition into the realm of the rich - manager magazin - company. Retrieved July 7, 2020 .

- ↑ Christian Rickens, DER SPIEGEL: Upper-class milieus: Germany, your rich - DER SPIEGEL - economy. Retrieved July 7, 2020 .

- ^ A b Stefan Bach, Markus Grabka: Party supporters: the wealthy tend to Union and FDP - and to the Greens . In: DIW (Ed.): DIW weekly report . No. 37 , 2013 ( online (PDF) ).

- ↑ Bundesbank

- ↑ Werkstatt Ökonomie e. V. (Ed.): Is there such a thing as poverty and wealth? For the social handling of definition and method problems . Heidelberg 2002, ISBN 3-925910-04-2 .

- ↑ a b The rich get richer, the poor get poorer - and the middle class is shrinking. November 6, 2018, accessed on August 2, 2019 (40,639 euros / 12 = 3,387 euros).

- ↑ Study: Poverty and wealth in Germany are solidifying. Retrieved March 14, 2020 .

- ↑ Wittmann, Sallmon, Meinlschmidt: health and social structure atlas of the Federal Republic of Germany . Ed .: Berlin Senate Department for Health and Social Affairs. 2015, p. 33 ( online (PDF) ).

- ↑ Federal Statistical Office: Income and Consumption Sample - Task, Method and Implementation. P. 9. In: Fachserie 15, issue 7, economic calculations, item number: 2152607089004, Federal Statistical Office , Wiesbaden, 2013.

- ↑ Federal Statistical Office: Sample Income and Consumption - Income Distribution in Germany. P. 7. In: Fachserie 15 Heft 6, WirtschaftsrechUNGEN , Federal Statistical Office, Wiesbaden, 2012.

- ^ Federal Statistical Office: Quality of the results of the EVS 2008. In: Fachserie 15, Heft 7, Wirtschaftsrechnungen. Sample of income and expenditure. Task, method and implementation. P. 39. Federal Statistical Office, Wiesbaden, 2013.

- ↑ a b Income millionaires are rarely screened by the tax office. Retrieved February 27, 2020 .

- ↑ a b Federal Government: Response of the Federal Government to Small Inquiry - Printed matter 19/13748 . Ed .: German Bundestag. Berlin October 4, 2019 ( online [PDF]).

- ↑ GEO Magazine No. 10/07: GEO survey: What is fair?

- ↑ Focus: Salaries of the CEOs of DAX companies [1]

- ↑ - ( Memento of the original from August 23, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Bernd Kramer: Association of Taxpayers: Impossible Lobby . In: The daily newspaper: taz . August 6, 2012, ISSN 0931-9085 ( taz.de [accessed June 20, 2020]).

- ↑ Why Taxpayers Remembrance Day is a deliberate deception. July 15, 2019, accessed June 20, 2020 .

- ↑ Infographic: Who Votes Who? Retrieved March 29, 2020 .

- ↑ bundestag.de (PDF)

- ↑ Federal Government: Answer of the Federal Government to Small Inquiry - Printed matter 19/8837 . Ed .: German Bundestag. Berlin March 29, 2019 ( online [PDF]).

- ↑ BMF - Official Income Tax Manual - EStH 2017 - § 32a - Income tax rate. Retrieved May 23, 2020 .

- ↑ Lea Elsässer, Svenja Hense, Armin Schäfer: Systematically distorted decisions? The responsiveness of German politics from 1998 to 2015. Ed .: Federal Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs (= poverty and wealth reporting of the federal government ). 2016, ISSN 1614-3639 .

- ↑ Andreas Haupt, Gerd Nollmann: Why are more and more households at risk of poverty ?: To explain increased poverty risk rates with unconditional quantile regressions . In: KZfSS Cologne journal for sociology and social psychology . tape 66 , no. 4 , December 2014, ISSN 0023-2653 , p. 603–627 , doi : 10.1007 / s11577-014-0287-0 ( online (PDF) [accessed on June 16, 2020]).

- ↑ Andreas Haupt, Gerd Nollmann: The gap opens: New wealth of income in reunified Germany . In: KZfSS Cologne journal for sociology and social psychology . tape 69 , no. 3 , October 2017, ISSN 0023-2653 , p. 375–408 , doi : 10.1007 / s11577-017-0482-x ( online (PDF) [accessed June 16, 2020]).

- ↑ Source: Statistics Austria, income tax statistics 2003

- ↑ Covid-19 - Millionaires are demanding higher taxation of their wealth to alleviate the corona crisis. Retrieved on July 17, 2020 (German).

- ^ Financial Times. Retrieved July 17, 2020 .

- ↑ Stuttgarter Nachrichten, Stuttgart Germany: "Millionaires for Humanity": Millionaires are demanding higher taxes for the rich because of the corona crisis. Retrieved July 17, 2020 .

- ↑ Meet the millionaires who want to be taxed to pay for the coronavirus. Retrieved July 17, 2020 .

- ↑ TC McLuhan: ... Like the breath of a buffalo in winter. Hoffman and Campe, Hamburg 1984. p. 96

- ↑ Anna Schriefl: Plato's Critique of Money and Wealth. Walter de Gruyter, March 22, 2013.

- ↑ Heinz Abosch: The end of great visions. Junius, Hamburg 1993. p. 124

- ↑ Edward Goldsmith : The Way. An ecological manifesto. 1st edition, Bettendorf, Munich 1996. p. 365

- ^ Friedrich Nietzsche: The wanderer and his shadow. In KSA vol. 2 p. 313

- ↑ Erich Fromm: To have or to be. The spiritual foundations of a new society . Munich: dtv, 2010, 37th edition, 271 pp. ISBN 978-3-423-34234-6

- ↑ Martin Schürz: About wealth . Campus Verlag, 2019, ISBN 978-3-593-44302-7 ( limited preview in Google Book Search [accessed March 23, 2020]).

- ↑ Vermögensforscher: "The rich endanger the goal of political equality" - derStandard.at. Retrieved March 23, 2020 .

- ↑ Controversy Over Wealth and Justice - Do We Need a Cap on Wealth? Retrieved March 23, 2020 .

- ↑ Cornelia Meyer: Billionaires can amass gigantic fortunes - because they have more power than you think. October 11, 2019, accessed March 23, 2020 .

- ↑ Big Mountain Action Group eV (Ed.): Voices of the earth. Raben, Munich 1993.