Solon

Solon ( ancient Greek Σόλων Sólōn [ só.lɔːn ]; * probably around 640 BC in Athens ; † probably around 560 BC) was an Athenian statesman and poet. In view of the otherwise sparse and uncertain tradition on the actors and developments in archaic Greece , especially with regard to chronological issues , the evidence of Solon's work is comparatively rich. This gives the impression that Solon, as a social analyst, politician and reformer in a profound crisis in the Attic polis , but also as a poet, philosopher and orator, gained an exceptional reputation early on, which still radiates today.

In ancient times, Solon was counted among the seven wise men of Greece . Modern research is primarily concerned with his political thinking and acting as the pioneer of a development that led to Attic democracy in Athens' classical times . Outstanding features of the understanding of politics he conveyed were, on the one hand, the prohibition, reversal and ostracism of debt slavery in Athens; .

Instead of combining his prominent position as reorganizer and legislator of the Athenians with the pursuit of sole rule ( tyranny ), as his fellow citizens probably expected of him, Solon left his hometown for a long time after completing the reforms and went on trips. The new order was therefore the responsibility of the citizens and, in terms of their effectiveness, relied on their handling of it.

Unclear tradition

Some aspects of the tradition of Solon are dubious, uncertain to the improbable and controversial. The uncertainties relate to aspects of Solon's vita, reform activities and legislation, as well as the surviving fragments of his poetry, which are only passed down in testimonies from later centuries.

Nevertheless, the problematic elements of the tradition also belong to an overall representation of Solon; for the significance of such a historical personality with an after-effect from a distant past is based not only on what he was and did, but also on what was and is ascribed to him. For Solon, this particularly applies to the role and share in the creation of Attic democracy . Both dimensions - what is well established as well as what is strongly doubted - are reproduced below, where possible with an appropriate allocation. An outline of the scope for interpretation associated with the lack of clarity in the source situation according to the latest research can be found below.

Cosmopolitan Athenian

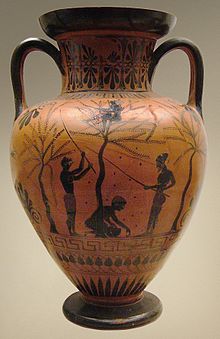

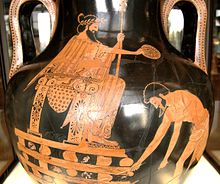

As the son of Exekistides, Solon is said to come from the Medontid family, which can be traced back to the mythical last Athenian king Kodros . According to Plutarch's testimony, Solon's mother also came from an aristocratic family and was the cousin of the mother of the later tyrant Peisistratos . However, Solon is said not to have been one of the particularly rich in the aristocratic Athenian ruling class. In contrast to many of his peers, who viewed anything other than agricultural income as unworthy, Solon also seems to have been involved in supraregional commercial transactions. As early as the end of the 7th century BC Athenian pottery and vase painting can be found in isolated cases in the Nile Delta and near Massilia ( Marseille ). It is possible that at this time the export of Athenian olive oil began.

Eloquent military strategist

Not involved in the Greek colonization of the Mediterranean and still insignificant in trade, for example compared to Corinth and Megara , Athens had only one strategically insignificant seaport in eastern Attica until the time of Solon. Improved development opportunities for the Attic sea trade depended on the fact that the island of Salamis off Athens , which the Megarians owned, came under Attic control. Promoting this plan intensively and uniting the fellow citizens with a high level of personal commitment in this goal, Solon also played a leading role as a military strategist in the conquest of Salamis.

However, the arguments between the Athenians and the Megarians in this regard were apparently changeable and protracted. The decision in favor of Athens may not have been made until the second quarter of the 6th century BC. With the important contribution of Solon's distant relative Peisistrato. In any case, it was in this context that Solon gained attention, prestige and influence among his fellow citizens.

In covenant with the Oracle of Delphi

Solon's special position among the Athenians is said to have contributed to his commitment to the defense of the famous ancient oracle site at Delphi , for which he vigorously campaigned. The Delphic priests had asked for help against the Crises, who controlled the access to the sanctuary from the sea and severely inflicted charges on those arriving to Delphi. Some of the oracle's particularly close poles , including Athens, represented by Solon, declared the first “holy war” to the crises in the name of the Delphic Amphictyony , which ended with the destruction of Crisis.

Via his connections to Delphi, Solon was connected to the non-Athenian spiritual currents of his time. In the course of the Greek colonization, the oracle site had become an important hub for thoughts and information from the entire Greek polis world. In addition to technical and geographical issues related to the establishment of a colony, problems of political organization and social and economic policy measures played an important role. Crisis developments in various poles and possible solutions were reflected in Delphi and by the thinkers active in this area. With regard to problems of political order, Solon could have played a special role, possibly that of a pioneer.

Thinker of the political

References to the political and programmatic core ideas of Solon arise mainly from the traditional fragments of his elegies. They were presented publicly and were intended on the one hand to win the audience over to the principles contained therein in the current crisis situation in the polis, on the other hand to ensure their dissemination and permanent anchoring as poetry in this still “oral” society. In Solon's verses, the image of a community that was justly regulated by law and supported by the participation of the citizens was sketched for the first time. The community-building term “our polis” can be found first with him. The good social order sought by Solon, the eunomy, supposedly aimed at restoring an earlier social order that had got out of balance. Nevertheless, for the historian Christian Meier , for example, it was great discoveries that Solon presented in his elegies: both the just order, which deviates significantly from the status quo, and the citizens' direct responsibility for the weal and woe of the polis.

Crisis of the polis as a social community

The reason for Solon's appointment to the prominent function of the mediator and conciliator of the Athenian citizenship with extensive powers for a reorganization of the situation was a profound social division, caused by increasing existential needs and debt slavery in the impoverished arable citizen milieu. The causes of an apparently acutely worsening debt crisis among parts of the bourgeoisie are seen in a reckless pursuit of profit at the expense of the small farmers, widespread among the ruling aristocratic large landowning circles. The rich man was able to make a fellow citizen in debt his debt slave - if he could not pay his debts - and even to sell him outside Athens. The resulting widespread fear of other people at risk of poverty, of losing personal freedom with their livelihood, triggered, among other things, radical demands for equal land ownership (Isomoria) for all Attic citizens. However, this questioned the foundations of the entire previous social order, so that Solon's appointment to arbitrator was also supported by not a few wealthy in the traditional leadership class.

Solon himself propagated the insatiability and greed of leading circles as the origins of the crisis in his hometown, who disregarded the traditional order and sometimes robbed what belonged to everyone. He castigated the servitude and sale of citizens abroad and declared that not a single citizen could escape the disastrous consequences of the internal quarrels of the polis, since everyone would be overtaken by them in their own homes and property.

Just order and organization of the polis: eunomy

The haunting, imagery language of the surviving fragments of Solon's elegies shows that he is not primarily concerned with a sober description of the state or even a detailed analysis, but certainly also with grabbing and dragging the addressees of his message. While, on the one hand, he urges fellow citizens to use reason, moderation and self-control, on the other hand, his poetry reveals that on the way to a new civic morality it is not enough to speak to the mind, but that such a reorientation is anchored in other areas of the human psyche must be.

In research it is controversial and unclear to what extent Solon himself sees divine forces at work in the polis; What is clear, however, is that he emphasizes human misconduct as the cause of the crisis in a hitherto unknown clarity and at the same time refers to the Zeus daughter Dike as the embodiment of law and criminal justice. Also Eunomia has could use the attributes of holiness that Solon for its renewal approach as a sister of the dike. In sharpest possible contrast to dysnomy - the gross undesirable development that has occurred with social upheavals - Solon praises eunomy as an effective remedy for the polis in their distress: “It smooths out rough things, puts an end to greed, outrage weakens it, […] it ends works the discord, painful quarrel bitterness ends, and everything is suitable and reasonable through them. "

As a divine symbol for a well-ordered community, Solon sees eunomy as "the epitome of order that should be striven for by all citizens in a joint effort." Solon expresses himself in the details of the nature of this community order, which is to be shaped by everyone and benefits everyone received elegies not. But he leaves no doubt that he sees himself called and able to show his fellow citizens the way to such an order: "To teach this to the Athenians is my urgent concern [...]"

State and community in everyone's responsibility

For Michael Stahl, eunomy in the sense of Solon can not be understood as a description of the situation, but as the embodiment of a process fed by the activities of the citizens with the aim of putting the conditions in their own community in order and developing them as best as possible. The entire Athens citizenry, according to Karl-Wilhelm Welwei , is called by Solon to recognize the connection between the excessive greed of the powerful and the resulting misery of the poor. As the citizens identify with the polis by each acting legally, the polis order is shared by all and the just order in public life is restored.

In order to strengthen the shared responsibility and participation of all citizens in the Polisverband in general, Solon made some precautions in his reform work. In the area of political institutions, he created a council of 400 with its own competencies as a counterbalance to the pure representation of the nobility in Areopagus . The people 's courts set up by him also brought new opportunities for participation and joint responsibility for broader classes of citizens in a particularly important field of public order. With the introduction of the popular lawsuit , every citizen of Athens was entitled and encouraged to bring violations of the polis system to justice, especially by officials. The stasis law also required the commitment of all citizens to important community interests, which obliged everyone to take sides with one of the sides in the event of an uprising in the citizenship. The Solonic origin of this law is, however, mostly doubted or rejected in recent research.

Even in any case, the program and content of Solon's work result in the realization that he laid the foundations for a political order associated with general civic responsibility and political participation. What the historian Thucydides later had his contemporaries Perikles say about Athens already fits Solon's concept of the polis : "For us, someone who is completely remote from the (political) is not called 'idle' but 'useless' ..."

Reformer in the state crisis

The question of when Solon was appointed to mediator ( Aisymnet ) in Athens and carried out his work of reform was usually associated in research with his election as archon and was dated to 594/593 BC. Dated. This position alone in the highest state office could have served him as a power base for such far-reaching reorganization measures. However, according to the sources, various inconsistencies were associated with this basic assumption for the chronology of the Solonic Vita and for the credibility of certain aspects of tradition.

Mortimer Chambers gives a number of reasons that speak in favor of dating Solon's reform work much later, including anarchic conditions in Athens in 590 and 586 and the "long archonate " of Damasias in 582-580 BC. He sees in it possible indications of a crisis, which could have preceded an extraordinary legislation. The ancient historians of the fifth century BC According to Chambers, for their part, for the purpose of dating the Solonic reforms, they might have simply taken Solon's archon as a fixed point due to a lack of precise knowledge. But Kleisthenes, for example, initiated his reform long after his own archonate. Chambers proposes the period between 575 and 570 BC for the Solonic reforms, taking into account other aspects. BC before. He is supported in z. B. von Charlotte Schubert : “The alternative would be to explain a great deal of the descriptions of his life, especially his travels and contacts with other historical people, as anachronistic or even fictitious. With that, however, one would lose an essential part of the ancient tradition. "

Concerning Solon's long-term effect and fame, the measures to restabilize the polis association and to institutionalize political participation were undoubtedly decisive. His reform approach also extended to important areas in the economy, society and law, which were supposed to contribute to a fundamental reorganization of the community. This included, among other things, impulses for Athens' foreign trade, a so-called coin reform, the introduction of upper limits for the accumulation of land holdings in the hands of individuals, and provisions on civil rights.

Elimination of debt slavery

The triggering moment for Solon's appointment to the role of mediator - and the cornerstone of his reform work, according to his own admission - was the smallholder debt crisis, which was generally threatening for the citizens of the Polis. Solon's approach to a solution consisted of a smooth cancellation of all the hectemorians' debts, who had to pay a sixth of their harvest to the creditor as debt repayment, and in the removal of all related markers (horoi) from the property of those affected. This "shaking off burdens" (Seisachtheia) also included the restitution of previous land holdings to Athens debt slaves with their bodies, including those who had already been sold outside of Attica and were now released.

When Solon forbade future access to the person of an insolvent debtor by law, he permanently eliminated the institution of debt bondage in Athens. No citizen of Attica had to face the loss of personal freedom for reasons of poverty. However, he resolutely opposed the demands for land reform with equal land ownership for all.

The traditional fragments of Solonic poetry also include those in which he justifies his measures. He points out that he has done justice to both sides. He gave the people what was due to them; but even the wealthy and powerful would not have suffered anything improper from him: "I stood up and threw a strong shield over them both, and I let neither of them win without the right."

Welwei sees Solon's Seisachtheia as one of the most momentous and important measures in the history of Athens. With the aim of securing internal peace, she not only defused an acute crisis, but also stabilized the social structure of the Athenian citizens in the long term.

Solons Legislation - Citizen Identity through Legal Community

Solon's decisive means to bring his far-reaching sociopolitical reform approach to the fore and to put it on a permanent basis was the written fixation of the new regulations in legal form. In an everyday political life still largely characterized by verbal communication, the use of writing promised increased effectiveness. The standard structure of the community has now become a central state institution, regardless of the situation and users.

The written safeguarding of the legal framework was made on wooden boards (axons), which formed an ensemble with four labeled outer sides connected at right angles to one another and which were rotatably attached to pegs in the manner of today's postcard stands. The law was originally intended to be valid for 100 years; but most of them remained in force until the end of the 5th century. And even after their replacement, they continued to be used until at least the end of the 3rd century BC. BC kept in Prytaneion in Athens .

On the first Solonic axon there was an export ban on foodstuffs with the exception of olive oil, which was probably to be seen as a flanking measure to Seisachtheia. Perhaps this was intended to ensure sufficient supplies for the poorer population in the critical transition phase after their liberation from economic and personal dependency. For Welwei, the restriction of the Athenian citizenship for immigrants also belongs in this context. Because only citizens were entitled to purchase land; while Solon reserved the existing land largely for "old citizens", in his view the chances for a functioning polis community and for a stable community should increase.

According to Welwei, community solidarity was at the center of the Solonic legal system. Because the living conditions in the archaic polis required diverse mutual assistance. The popular lawsuit introduced by Solon opened up an additional dimension in this regard, in that it was now also legally possible to take legal action to assist a fellow citizen who had been wronged by another party. Not only theft and robbery, but also the protection of the weak and minors in the event of embezzlement by their legal representatives or in the case of waste of assets, for example through idleness, could be the subject of the popular lawsuit.

The sweeping Solonic legislation, upon which all Athenians had to take the oath, as Herodotus testifies, created the conditions for a change in consciousness. The sacred figures of Dike and Eunomia were retained as moral reference values for the legal system; The decisive factor for the distinction between right and wrong was no longer the individual balancing act, but the legal system in written form and the legal community it established.

Income-dependent political participation - the Solonic timocracy

To reunite the polis community on a new basis was Solon's primary goal. For him, however, it was not about equality of citizens, neither in terms of land ownership and wealth distribution nor in terms of political power and influence. Rather, when designing the institutional structure, he ensured that, on the one hand, all citizens were encouraged to participate sustainably, but that their rights of participation were in line with their social position and income.

According to some controversial ancient tradition, it was part of Solon's specifications that every Athenian was obliged to state the amount of his annual income. The basis of assessment was dry or hollow dimensions, such as a certain bushel size ( Medimnos , approx. 52.8 liters) for grain and certain vessel sizes for olive oil and wine. When classifying the citizens according to the principle of timocracy , however, rather rough guidelines could have applied, because the ability to self- armed as a hoplite or rider was particularly important for the position in the polis association even before Solon . While the low-income citizens who could not afford hoplite armor belonged to the class of thets , the hoplites fighting in the phalanx formed the class of witnesses (from around 200 bushels annual income). Anyone who was able to keep a horse and equip it for battle belonged to the Hippeis class (from approx. 300 bushels). Those who had an even higher income at their disposal enjoyed the special privileges of the so-called Five Hundred Shepherds ( Pentakosiomedimnoi ).

Associated with the timocratic classification were graduated political rights of participation and the exercise of power in offices. Only five hundred shefflers could become treasurers (Tamiai) (because the polis could keep their property safe in an emergency); and other important offices such as the archonate were reserved for the two upper classes of wealth. If Solon had created a council of 400 as a new institution and counterweight to the Areopagus, who was reserved for the former archons, this council should also have aimed at expanding the possibilities for participation within the framework of the Solonic class scheme. However, neither the responsibilities of such a Council of 400 nor the persons authorized to access it have been passed down in a plausible manner. The 4th century BC Chr. Representation in the Athenaion politeia has raised many questions and doubts in research. Institutionalized political co-determination for the two lower classes of wealth existed above all in the people's assembly ( Ekklesia ) and in the people's courts closely connected to it ( Heliaia ). Here all full citizens were allowed to vote and judged either in the first instance or as an appeal body against decisions of office holders.

At the end of his investigation of the economic aspects of the Solonic reforms, Philipp V. Stanley comes to the conclusion that the polis community has experienced an increase in prosperity and a mobilization of resources outside of the agricultural sector. It was not a matter of the accumulated wealth, but of profitable, income-increasing economic activities of all kinds. From then on, the political position of the citizens was no longer determined so much by the property they had, but by the annual earned income - and decided descent within the Solonic timocracy. The law against inactivity and idleness, testified by Herodotus as still valid in his time, underlines Solon's efforts to activate the Athenian citizenship in a variety of ways.

Sage in ancient Greece

As a reformer and legislator, Solon managed to avert the impending civil war in Athens with a political reorganization. Apparently he was not granted much thanks for this for the time being; because he balanced the reactions received as follows:

“They thought hollow things back then, but now embittered with me / they all look at me crookedly like one looks at an enemy. / Not rightly! Because what I said, I have completed with the gods, / but I did not do anything else - it would have been hopeless - and I do not like to do anything with sole rule / power, not even that in the fat country / the fatherland, with the bad have the same share as the noble. "

Solon's interest and sphere of activity did not only extend to his own polis. Not long after completing the reform work, according to the sources, he developed an extensive ten-year travel activity and met other well-known contemporaries. In the fourth century BC BC the idea of a circle of the seven wise men from earlier times was consolidated among the Greeks , in which Solon had a permanent place and in which Plato even appeared as the "wisest of the seven".

Rule of law instead of tyranny

Important parts of the wisdom attributed to Solon result from his political thinking and actions. His guiding principle Eunomie aimed at the individual and shared responsibility of all citizens for the well-being of the polis community. He refused sole rule in the form of tyranny , which concentrated power and responsibility with one individual, not only with a view to others, but also for himself. He just had to seize the opportunity, as he remarked, not without irony: “By nature, Solon is not a sensible man with strong advice; / for although a god offered glorious things, he did not accept it; / He threw it out and - marveling at the booty - did not close the big / net, for courage and at the same time also lost his mind. ”

Switching from the outside to his own perspective, Solon explains his considerations: Although sole rule could have given him immeasurable wealth ; but then he would have exposed himself and with himself also his ancestors and descendants to the outlawing by the Athenians.

According to Solon, it is not fateful necessity or divine powers that prepare the ground for servitude and tyrannical violence, but rather naivety, a distorted perception of reality and the easy seduction of citizens who are only concerned with personal gain:

“If you continually suffer miserable things from your own wickedness, then do not give the gods of these things fate! / Because you yourself have empowered these people, giving protection, / and therefore you got bad bondage. / Of you, each of you walks in the footsteps of the fox, / but you all live together in holey insight. / Because you look at the stroke of your tongue and the words of a flattering man, / but you don't look at what is really going on. "

In addition to greed and selfishness, Solon also criticizes his fellow citizens for the short-sightedness of what they do and don't do. In contrast, in one of the fragments handed down from his poetry, he clearly underlines the opposite approach, namely to keep known dangers in mind and to prevent them effectively through appropriate action:

“From the cloud comes the violence of the snow and the hail, / thunder comes from the flaming lightning; / The city perishes through mighty men, and in the bondage of the sole ruler / the people overthrow through ignorance. / Whoever is lifted up too far cannot be tamed easily / later, but now you have to think about everything <wisely> (?). "

Solon also reflected and calculated his own interests in the long-term perspective:

“If I have spared the country, / the fatherland, and sovereignty and power, the inexorable, / not touched and thus not defiled or desecrated my name, / I am in no way ashamed. Because then I will - I think - more likely to win / over all people. "

To travel

In the ancient tradition, traveling was part of the image of the sage. As a traveler, Solon appears to Herodotus and Plutarch especially after his reform work, which the Athenians now apply and fill with life without him as a community of citizens. His travel activities took him to Egypt, among other places, but perhaps not there for the first time, as Herodotus suggests. He points to a law of Pharaoh Amasis , which Solon is said to have taken over: “Amasis also gave the Egyptians the following law: Every year every Egyptian has to tell the administrator of the district what he lives on, and whoever does not do that and has no legitimate income , is punished with death. Solon from Athens adopted this law from the Egyptians and introduced it in Athens. "

According to Plutarch, after a visit to Amasis, Solon met two particularly respected priests at Canopus in the area of the western mouth of the Nile, and there he got to know the myth of Atlantis while dealing with them philosophically . He then participated in its dissemination with an elegy himself, as Plato noted.

Solon's stay in Cyprus is also described as significant , where he advised King Philokypros on a city complex that is said to have proven to be particularly attractive. The grateful King named them Soloi after Solon . The honored one reciprocated in an elegy with congratulations: “May you and your family, long ruling over the Solier, live in this city, which is yours. But escort me on a hurrying ship from the glorious island of Kypris, wreathed with violets. May she give me thanks for the founding of the city and glory, and return home to the land that is ours. "

Teacher of Croesus?

Solon's appearance as a sage in the encounter with the Lydian king Kroisos in Sardis is shown in particular in the sources . Whether this event took place at all was already very doubtful in ancient times. Plutarch explains his adherence to it and his own extensive account of this encounter with his refusal to share “such a famous story, told by so many witnesses, which, more importantly, corresponds to the character of Solon and is worthy of his high disposition and wisdom For the sake of so-called chronological tables, which innumerable people can improve on and yet still cannot find a general solution to the contradictions ”. According to Chambers, the comparison of Solon's travel dates and life stations with the reign of Croesus leaves little room for a meeting, even from today's perspective: "Chronologically difficult, but not entirely impossible".

According to the accounts of Herodotus and Plutarch, Solon was hospitably received in Sardis and thoroughly familiarized with the splendor of court life and the wealth of palace treasures. After four days, Croesus asked who he, Solon, who had traveled so far and who had a reputation for special wisdom, considered the happiest of people. To the disappointment of his host, Solon named Tellos from Athens in the first place and, when asked, the Argive brothers Kleobis and Biton in second place . Solon attested to Tellos as well as the brothers and sisters that they had not only lived exemplary righteousness, but had also met their deaths in full honor. According to tradition, it aroused disbelief and anger in Croesus that such simple citizens should be ahead of him in luck. Solon tried to placate him by declaring that no one could be considered blissful before his end, but only when he had ended his life in good pleasure.

In view of his future fate, Croesus had reason to remember Solons. First he lost the heir to the throne through the death of his son Atys; then he gambled away his kingdom in the war against the Persian king Cyrus II . Brought to the stake by him, he is said to have called out Solon's name several times, thereby arousing Cyrus' curiosity and finally being spared. Plutarch closes his account on this by pointing out that Solon has the fame of having both saved Croesus' life and made another king, Cyrus, wiser.

End of life

Returning to Athens, Solon tried in vain to counteract the rifts that had broken out again in the city and to resist the impending Peisistratiden tyranny . Plutarch's description, according to which Solon went to the market to call on fellow citizens once more to defend the freedom of the community in a haunting speech, appears doubtfully over-shaped by the formation of legends. In the absence of a response, he then went home and put his weapons in front of the door on the street with the declaration that he had now defended the polis and laws according to his strength. He spent the rest of his life in seclusion and tranquility and even became an adviser to Peisistratos, who showed him all respect and largely allowed the Solonic legislation to continue.

Solon died in 560 BC Chr. Or soon after. Plutarch himself describes the fact that his bones were brought to Salamis and burned there, but the ashes were scattered all over the island, as an absurd fable.

Lively aftermath

In his roles as an exemplary wise man, reconciler and legislator of the polis community, Solon has achieved a fame that extends beyond Plato , Aristotle and Cicero to the present day. Authentic and legendary are merged into a complex unit that research can at best be painstakingly differentiated. Uncertainties in determining the actual historical location of Solon are mainly due to the fact that the authors of the main literary sources on Solon, namely Herodotus , Aristotle and Plutarch , only reported about him and his work more than one to seven centuries after Solon's death to have.

Whereas in antiquity it was mainly Solon's qualities, which were recorded in sayings, that were significant as wise men, modern research is more concerned with Solon's acting as a state and social reformer and especially his importance for the development process of Attic democracy . In one of the most recent studies - of Solon, "the thinker" - two presidents of the United States are quoted: James Madison as an admirer of the "immortal legislature" Solon, Woodrow Wilson with his assessment that Solon gave Athens an established and unambiguous constitution.

Solonic sentences

The following collection of Solonic proverbs shares the uncertainties that result from the source situation as a whole. The surviving fragments of Solon's elegies, which seem to come from literal tradition, can only be proven in records from later centuries. Some can be found in the traditional fragments of his poetry, others from a compilation by Demetrius of Phaleron :

- It is difficult to please everyone, when it comes to an important deed. ἔργμασι (γάρ) ἐν μεγάλοις πᾶσιν ἁδεῖν χαλεπόν

- Indeed, in all works there is danger and no one knows / where it will end up when things begin; πᾶσι δὲ τοι κίνδυνος ἐπ᾿ ἔργμασιν, οὐδὲ τις οἶδεν / πῆι μέλλει σχήσειν χρήματος ἀρχομένου ·

- Nothing in excess. Μηδὲν ἄγαν.

- Do not sit in court or you will be an enemy to the condemned. Κριτὴς μὴ κάθησο εἰ δὲ μή, τῷ ληφθέντι ἐχθρὸς ἔσῃ.

- Flee lust, which gives birth to displeasure. Ἠδονὴν φεῦγε, ἥτις λύπην τίκτει.

- Keep your decency more true than your oath. Φύλασσε τρόπου καλοκαγαθίαν ὅρκου πιστοτέραν.

- Seal your words with silence, your silence with the right moment. Σφραγίζου τοὺς μὲν λόγους σιγῇ, τὴν δὲ σιγὴν καιρῷ.

- Don't lie, speak the truth. Μὴ ψεύδου, ἀλλ᾿ ἀλήθευε.

- Strive for seriousness. Τὰ σπουδαῖα μελέτα.

- I am no more right than your parents. Τῶν γονέων μὴ λέγε δικαιότερα.

- Do not make friends quickly; but do not quickly discard those you have. Φίλους μὴ ταχὺ κτῶ, οὓς δ᾿ ἂν κτήσῃ, μὴ ταχὺ ἀποδοκίμαζε.

- Learn to be ruled and you will know how to rule. Ἄρχεσθαι μαθών, ἄρχειν ἐπιστήσῃ.

- If you demand accountability from others, give it yourself. Εὐθύνας ἑτέρους ἀξιῶν διδόναι, καὶ αὐτὸς ὕπεχε.

- Do not advise the most pleasant, but the best to the citizens. Συμβούλευε μὴ τὰ ἥδιστα, ἀλλὰ τὰ βέλτιστα.

- Avoid bad company. Μὴ κακοῖς ὁμίλει.

- Be mild to yours. Φίλους εὐσέβει.

- Solon said the laws were like spider webs; like them, they held the small and weak captive, but the bigger ones could tear them apart and get free. Ἔλεγεν ( scil. Ὁ Σόλων ) τοὺς δὲ νόμους τοῖς ἀραχνίοις ὁμοίους

- I'm getting old and I'm still learning a lot. Γηράσκω δ 'αἰεὶ πολλὰ διδασκόμενος.

Legendary founder of democracy

In the description of the constitutional development of ancient Athens, contained in the Athenaion Politeia ascribed to Aristotle , the Solonic order is referred to as the beginning of democracy. With reference to the following, even more democratic, kleisthenic order and the radical democracy introduced by Ephialtes , Aristotle differentiates between three different stages or types of democracy in the development of the Attic polis. In more recent research, Solon's designation as the founder of democracy is often not accepted with a view to the social-hierarchical-timocratic tiered political participation rights and restrictions. On the other hand, it is almost undisputed that his work created important prerequisites for the future development of the Attic polis.

The initial situation before Solon's reforms was characterized by an internal weakness of the polis and its noble leadership. This encouraged the idea of own co-responsibility and the demands for institutionalized own participation, which in the long term led to the rule of the demos . The basic features of the Solonic order also outlasted the tyranny: "Peisistratos and his sons faced an association of persons that had already found its political form of being as a polis community and had gained a strong hold in its social and institutional order through the Solonic legislation."

The constitutional question

If one takes the extent and political effects of the Solonic reform work as a basis, the terms constitution and constitution-giver, which are actually used more often for it, are obvious. Nevertheless, Politeia in the sense of constitution for the Solonic period is an anachronistic term; only around 430 BC BC Politeia (originally: citizenship) in the sense of political order or constitution is certainly attested. This also expresses the correlation between civil rights, citizenship and the political system. As a politeia, the institutional regulations for the community in their entirety could now also apply. The Solonic eunomy, on the other hand, stood primarily for the tried and tested, for the right and the binding in human coexistence.

But as a role model for a wise legislator, Solon remained an undisputed authority in later centuries. The sole source of law was henceforth laws. The jurisprudence was bound by it and did not create any new law in practice, just as the forms of action survived unchanged. "In this way, principles, which can be explained from the regulatory and legal ideas of the archaic period, still determined the right to prosecute and sue and the related forms of litigation in classical times."

Attributions in Antiquity

Unlike Herodotus, who honors Solon as a lawgiver and wise man, he is not even mentioned in the history of Thucydides . In the Attic comedy of the 5th century BC Chr. Is Solon and its legislation is represented more often. Kratinos brings him to the stage in the play Cheirones as a representative of the good old days in the face of unpleasant conditions in the developed Attic democracy. Aristophanes names him in The Clouds as a "popular friend of nature". The orator Isocrates refers to Solon in the 4th century BC. Together with Kleisthenes as the most important creator of the Attic democracy and on other occasions as the “protector or ruler of the people”. While Isocrates praised him as the originator of moderate democracy, for Demosthenes he was the fatal initiator of radical democracy. According to Schubert, this made it very clear that Solon's name could be associated with very different values: his reputation as a time-honored personality, famous legislator and poet was so great that he could be used for impressive legitimization at any time without this being done to you specific content was set.

Aristotle honors Solon as a middle man: opponent of both an elitist oligarchy and radical democracy with the participation of the lower class poor, keeping a distance from those extremes which, according to Aristotelian ideas, both prepare the ground for tyranny. Cicero was also impressed by this, who often mentioned Solon's legislative activity and dealt theoretically and in letters with some of his laws. Like Plato, Solon, to whose verses he occasionally referred to in his philosophical writings, appeared to him "as the wisest man of the seven".

Evaluation by recent research

On the part of more recent research into ancient history, Solon is hardly regarded as the founder, but as a forerunner and forerunner of the developed Attic democracy: “With the comprehensively conceived power to shape the order of the community, with the postulated exclusion of a political area and with the discovery of the citizenry as Solon recognized the decisive conditions of the Athenian polis for the first time and brought to consciousness its central magnitude. The development in the centuries after him was shaped by their gradual realization. ”Solon's pioneering function for the classical democratic era of Athens results both in terms of the formation of political concepts and in the area of institutional development.

Solon's concept of eunomy preceded Kleisthenian isonomy , which in turn became the preliminary stage of the concept of democracy that was only developed afterwards. The reforms carried out in the aftermath of the Peisistratiden tyranny of Kleisthenes remained, like the Solonian, tied to the aristocratic-timocratic social structure, but created additional incentives for political participation and a common citizen identity of the Athenians with an institutionalized mixing of the citizens within the framework of the Phylenreform. Taking the introduced also in the era after the Peisistratids ostracism (ostracism) added that allowed the banishment of a particular political ambitious fellow citizen for 10 years, also in the continuing influence of Solon's advocacy against any tyrannical ambition is recognizable. Overall, Kleisthenes again brought about an upgrading of the concept of the citizen as well as increasing familiarity among citizens and solidarity towards the outside world. According to Kurt Raaflaub, this ultimately enabled the Athenians to become the leading political and cultural power in Greece.

Important economic decisions for the prominent position of Athens in the following centuries were already initiated by Solon with his reforms in this regard, according to Phillip V. Stanley in the summary of his relevant study. With regard to Solon's long-term political impact, Michael Stahl sums up: “With the recognition of the primacy of politics as well as of the importance of political ethics and the function of the political culture, Solon set up the cornerstones of the civil state and established the coordinates within which Athenian history is in the 6th and 5th centuries Century should move. From this perspective, the archaic and classical history of Athens unite to a much greater extent than has been seen in recent times. "

Sources and source-critical analysis

With Herodotus, the "father of historiography", Aristotle, the founder of the Peripatetic school of philosophy and systematist of knowledge of his time, and Plutarch, the moralist and historical biographer of a large number of important Greeks and Romans, the tradition of Solon is based on the one hand on great names. On the other hand, the time lag between these testimonies and the Solon's era and the source authors' own interests that flow into it cause many doubts and critical reflections.

Herodotus

The first ever surviving biographical references to Solon can be found in Herodotus, who mentions him as an Athenian lawgiver, but mainly deals with the traveling sage Solon. Consisting of Halicarnassus originating Ionians Herodotus was the epics of Homer trained and was close to the contemporary Attic drama. In addition to the results of conscientious and precise studies that Herodotus collected on far-reaching journeys, dramatic effects and legendary elements can also be expected with him. Solon's encounter with Kroisos and his invocation of Solons at the stake, for example, may have been shaped by Herodotus in this way.

Aristotle

Unlike Herodotus, the Athenaion Politeia , written by Aristotle (or one of his students), offers a detailed account of the Solonic reform work as a landmark in the development of the Athens constitution. In view of the shortage of original sources that existed for Aristotle, from the point of view of Chambers the Athenaion Politeia is “a work of clever restoration”. However, this does not mean a reconstruction that is authentic and free of contradictions in every respect. Thus, in the Constitution of the Athenians from the introduction of a Council of 400, the speech, while Aristotle elsewhere in his state theory signature policy that is not mentioned and instead the corresponding relationship finds Solon have on the role of the Areopagus not changed.

Likewise, the claim in the Athenaion Politeia of the introduction of the lottery procedure for appointments to offices by Solon does not seem to fit together with the statement in politics that the previous procedure was also retained in the election of officials. Chambers interprets this disagreement as an expression of a changed view of Aristotle in relation to the development scheme of Attic democracy, in such a way that Solon was only awarded the introduction of the people's courts, the lottery and a second council by Aristotle in the Athenaion Politeia . Hans-Joachim Gehrke , on the other hand, does not consider these deviations incompatible and understands them as the consequences of a slightly different focus of attention in the representation: Solon was both the keeper and the innovator. In politics , its role as a keeper is more strongly emphasized; in the Athenaion Politeia his profile as a reformer.

Plutarch

From the comparatively longest period of time, Plutarch gave the richest ancient account of Solon's vita, reform approach, legislation and role as a sage. In the biographies of famous Greeks and Romans, it was not so much the historical details and connections that mattered to him, but the clarification of supposedly typical characteristics and peculiarities of the respective personality. Michael Grant attested that he had a unique talent in the selection of telling anecdotes. He was a master at arousing readers' interest and keeping them awake. However, his reliability in fact fluctuates strongly, due to the selection principles for his life images, which led to distortions. Moreover, in Plutarch's time it was often impossible to separate the legendary from the credible among the material that was available to him on Solon.

Nonetheless, according to Lukas de Blois, Plutarch did not manipulate the basic historical and biographical information still available to him, but only its arrangement and use in the context of the presentation. Stereotypes, platitudes and patterns from other descriptions of his life - according to the good statesman, the interactions between aristocratic leaders and the general public or the right kind of mental preparation of the masses for political reforms - can also be found in the Solon portrayal. This is due to the apparently meager sources, which Herodotus did not have much written about Solon and Thucydides nothing at all. However, Plutarch undoubtedly evaluated the available facts from his sources, including lost chronicles of Athens and other historical works, in the usual careful manner.

Current aspects of the Solon reception

A striking newer research feature is the merging of results from different specialist disciplines and their mutual comparison in the dialogue between ancient historians, for example with philologists and archaeologists. As a poet and fundamental reformer rolled into one, Solon offers plenty of material for this. Michael Stahl emphasizes the important function of Solon's poetry for his political work. Through his identification with the cunning tactician Odysseus , who knew how to assert himself less with the power of the sword than with convincing speech, Solon had used the myth for his own goals. He also conveyed the new political ethics propagated by him in accordance with the main religious currents of the time, in particular based on the commandment of moderation issued by the Delphic priesthood ( μηδὲν ἄγαν - “nothing too much”).

One of the focal points of more recent Solon research - referred to by Fabienne Blaise as a "solonian question" - is directed to the question of whether the elegies handed down under Solon's name actually reproduce his verses true to the original. André PMH Lardinois justifies his doubts about this by pointing out that in one case it can be proven that two incompletely identical versions of a Solon poem have survived, and as a consequence expresses general doubts about the authenticity of the verses handed down as Solonic, especially with regard to political poetry. Eva Stehle considers the political poems traced back to Solon to be products of the 4th century BC. BC, arose out of the need to make Solon the witness and ancestor of each individual's own conception of democracy. Fabienne Blaise admits that no proof of authenticity can be provided for any of the poems that have survived as Solonic. But she deduces from the analysis of the Eunomia elegy, which she regards as completely preserved, that it is the expression of a for the 6th century BC. Both original and coherent position, which can also be found in other fragments of Solon's poetry.

More recent research also poses similar questions of allocation to the laws that have been handed down as solonic. In this context, Adele C. Scafuro suggests adding to the distinction between genuinely Solonic and non-Solonic laws established since Eberhard Ruschenbusch's study in 1966 as a third category of laws “with a solonic core”. PJ Rhodes also follows this approach to the separate recording of laws that have an authentic Solonic core but were later modified.

John Lewis' essay on the thinker Solon is directed to Solon's contribution to the establishment of a polite welfare bourgeois mentality. Lewis emphasizes that Solon did not make this contribution as an isolated observer and theorist, but in the midst of tumultuous disputes among his fellow citizens. Against the vices of pride and selfishness that are destructive to the community, Solon promoted and demanded self-control in word and deed as well as respectful action in relation to others. He has strengthened the independence of his own judgments and actions in an exemplary way by not giving in to social pressure, but instead turning only to the objective requirements.

As the founder of a certain legal awareness and a legal tradition based on law, Solon is not only portrayed in Lewis, but also in Joseph Almeida's study Justice as an aspect of the polis idea in Solon's political poems: a reading of fragments in light of the researches of new classical archeology. In doing so, Almeida combined the evaluation of Solon's political poetry - especially in relation to the understanding of law symbolized by Dike - with the Polis image, which recent archaeological research for the 6th century BC. Chr. Draws. His conclusion is that Solon's poetic description of the situation in Athens is broadly in line with archaeological research and conclusions for that period.

See also

Text output

- Eberhard Ruschenbusch : Solonos Nomoi. The fragments of the Solonic legal work with a text and tradition history (= Historia individual writings. Issue 9). Wiesbaden 1966. Still authoritative edition of the fragments of the Solonic laws. A posthumous new publication based on the manuscript by R. with German translations and comments was made by Klaus Bringmann:

- Eberhard Ruschenbusch: Solon: The law fragments. Translation and commentary. Edited by Klaus Bringmann (= Historia individual writings. Issue 215). 2nd, corrected edition. Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-515-10783-9 ; see. the review of the first edition, Stuttgart 2010, by Winfried Schmitz in Sehepunkte .

- Delfim F. Leão, Peter J. Rhodes (Eds.): The Laws of Solon. A New Edition with Introduction, Translation and Commentary. Tauris, London 2015, ISBN 978-1-78076-853-3 (latest publication of Solon's Laws with English translation and commentary based on E. Ruschenbusch).

- Christoph Mülke (Ed.): Solon's political elegies and Iamben (Fr. 1–13; 32–37 West). Introduction, text, translation, commentary. Munich / Leipzig 2002.

- Martin L. West (Ed.): Iambi et elegi Graeci ante Alexandrum cantati. Vol. 2: Callinus. Mimnermus. Semonides. Solon. Tyrtaeus. Minora adespota. 2nd Edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1992, ISBN 0-19-814096-7 , pp. 139-165.

- Bruno Gentili-Carolus Prato (ed.): Poetae Elegiaci, Testimonia et Fragmenta. Part 1: Tyrtaios. Mimnermus. Solon. Asius. Phocylides. Xenophanes. 2nd, improved edition. Leipzig 1988, ISBN 3-322-00457-0 , pp. 61-126.

- Eberhard Preime: Solon: Seals. All fragments. Translated into German in meter of the original text. Greek and German. 3rd, improved edition. Munich 1945, ISBN 978-3-11-035772-1 .

literature

- Andreas Bagordo : Solon. In: Bernhard Zimmermann (Hrsg.): Handbook of the Greek literature of antiquity , Volume 1: The literature of the archaic and classical times. Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-406-57673-7 , pp. 169–175 (about Solon as a poet).

- Josine Blok, André PMH Lardinois (eds.): Solon of Athens. New Historical and Philological Approaches. Leiden / Boston 2006 (current contributions, some of which radically question the historicity not only of the traditional events, but also of Solon's person himself).

- Lin Foxhall : A View from the Top: Evaluating the Solonian Property Classes. In: Lynette G. Mitchell / Peter J. Rhodes (Eds.): The Development of the Polis in Archaic Greece. London / New York 1997, pp. 113-136.

- Hermann Fränkel : Poetry and philosophy of the early Greek culture. 5th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-406-37716-5 , pp. 249-273.

- Wolf-Dieter Gudopp-von Behm : Solon of Athens and the discovery of the law. Würzburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-8260-4119-8 (a complex study of Solon's history of philosophy in an archaic context with a formal-content analysis of the poetic fragments).

- Edward M. Harris: Did Solon Abolish Debt Bondage? In: Classical Quarterly. Volume 52, 2002, pp. 415-430.

- John Lewis: Solon the Thinker. Political Thought in Archaic Athens. London 2006.

- Gregory Nagy, Maria Noussia-Fantuzzi (Ed.): Solon in the Making: The Early Reception in the Fifth and Fourth Centuries (= Trends in Classics. Volume 7, Issue 1). De Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2015.

- Pavel Oliva: Solon - legend and reality (= Konstanz ancient historical lectures and research. Volume 20). Konstanz 1988, ISBN 3-87940-331-7 .

- Charlotte Schubert : Solon. UTB Profile, Tübingen / Basel 2012, ISBN 978-3-8252-3725-7 .

- Michael Stahl : Solon F 3D. The birth of the democratic idea. In: Gymnasium . Volume 99, 1992, pp. 385-408.

- Phillip V. Stanley: The economic reforms of Solon. St. Katharinen 1999.

- Isabella Tsigarida: Solon. Founder of democracy? An examination of the so-called mixed constitution of Solon of Athens and its democratic components. Bern et al. 2006 (a more recent presentation and interpretation, the methodological and content-related deficiencies are certified. Review by W. Schmitz in Sehepunkte / Review by Monika Bernett in h-soz-kult ; PDF file; 84 kB).

- Robert W. Wallace: The Date of Solon's Reforms. In: American Journal of Ancient History. Volume 8, 1983, pp. 81-95.

Web links

- Literature by and about Solon in the catalog of the German National Library

- Lars Leithold: The reforms of the Solon

Remarks

- ↑ See e.g. B. Norbert Ehrhardt : Athens in the 6th century BC Source situation, method problems and facts. In: Euphronios and his time. Staatliche Museen, Berlin 1992, pp. 12–23; Mortimer Chambers : Excursus: On the Chronology of Solons. In: Mortimer Chambers: Aristotle, State of the Athenians. Translated and explained by Mortimer Chambers. Berlin 1990, pp. 161-163; Pamela-Jane Shaw: Discrepancies in Olympiad Dating and Chronological Problems of Archaic Peloponnesian History. Stuttgart 2003 ( review ).

- ^ Kurt Raaflaub : Introduction and balance sheet. In Konrad Kinzl (ed.): Demokratie. The way to democracy among the Greeks. Darmstadt 1995, p. 9 f.

- ^ Hartwin Brandt : Solon. In Kai Brodersen (ed.): Great figures of Greek antiquity. Munich 1999, p. 84 f.

- ↑ Pavel Oliva: Solon - legend and reality. Konstanz 1988, p. 37; Hartwin Brandt: Solon. In: Kai Brodersen (Ed.): Great figures in Greek history. Munich 2001, p. 85; Chambers expresses himself very doubtfully in: Aristotle: The State of the Athenians. Translated and explained by Mortimer Chambers. Darmstadt 1990. p. 162 f.

- ^ Hartwin Brandt: Solon. In: Kai Brodersen (Ed.): Great figures in Greek history. Munich 2001, p. 85.

- ↑ Pavel Oliva: Solon - legend and reality. Konstanz 1988, p. 29.

- ↑ Pavel Oliva: Solon - legend and reality. Konstanz 1988, pp. 40-45.

- ↑ Pavel Oliva: Solon - legend and reality. Constance 1988, p. 45 f.

- ↑ Christian Meier: Origin and peculiarity of the Greek democracy. In Konrad Kinzl (ed.): Demokratie. The way to democracy among the Greeks. Darmstadt 1995. p. 269 f.

- ^ Hartwin Brandt: Solon. In: Kai Brodersen (Ed.): Great figures in Greek history. Munich 2001, p. 85; Pavel Oliva: Solon - legend and reality. Konstanz 1988, p. 78.

- ↑ Oswyn Murray calls Solon's poems “a directly political poetry” (Oswyn Murray: Das early Greece. Translated by Kai Brodersen. Munich 1982, p. 230).

- ↑ John Lewis: Solon the Thinker. Political Thought in Archaic Athens. London 2006, pp. 1 and 20.

- ↑ Christian Meier: Origin and peculiarity of the Greek democracy. In Konrad Kinzl (ed.): Demokratie. The way to democracy among the Greeks. Darmstadt 1995, p. 266.

- ^ Karl-Wilhelm Welwei : Athens. From the beginning to Hellenism. Volume 1: Athens. From the Neolithic settlement to the archaic Greater Polis. Bibliographically updated one-volume edition, Darmstadt 2011 (original edition 1992), pp. 154–160.

- ↑ Solon, Fragment 4, 5-29 (West); Christoph Mülke (Ed.): Solon's political elegies and Iamben (Fr. 1–13; 32–37 West). Introduction, text, translation, commentary. Munich / Leipzig 2002, pp. 43–45.

- ↑ Christoph Mülke (ed.): Solon's political elegies and Iamben (Fr. 1–13; 32–37 West). Introduction, text, translation, commentary. Munich / Leipzig 2002, p. 91.

- ↑ Michael Stahl : Solon F 3D. The birth of the democratic idea. In: Gymnasium . Volume 99, 1992, pp. 402 f.

- ↑ Solon, Fragment 4, 32-39 (West); Christoph Mülke (Ed.): Solon's political elegies and Iamben (Fr. 1–13; 32–37 West). Introduction, text, translation, commentary. Munich / Leipzig 2002, p. 45.

- ^ Karl-Wilhelm Welwei: Athens. From the beginning to Hellenism. Vol. 1: Athens. From the Neolithic settlement to the archaic Greater Polis. Bibliographically updated one-volume edition, Darmstadt 2011 (original edition 1992), p. 150.

- ↑ ταῦτα διδάξαι θυμὸς Ἀθηναὶους με κελεύει (Solon, Fragment 4, 30 (West); Christoph Mülke (Ed.): Solonspolitische Elegien und Iamben (Fr. 1–13; 32–37 West). Introduction, text, translation, commentary . Munich / Leipzig 2002, p. 45)

- ↑ Michael Stahl: Solon F 3D. The birth of the democratic idea. In: Gymnasium. Volume 99, 1992, p. 398.

- ^ Karl-Wilhelm Welwei: Athens. From the beginning to Hellenism. Vol. 1: Athens. From the Neolithic settlement to the archaic Greater Polis. Bibliographically updated one-volume edition, Darmstadt 2011 (original edition 1992), p. 150 f.

- ↑ Thucydides 2.40; quoted by Michael Stahl: Solon F 3D. The birth of the democratic idea. In: Gymnasium. Volume 99, 1992, p. 402.

- ↑ Aristotle: The State of the Athenians. Translated and explained by Mortimer Chambers. Darmstadt 1990, p. 161 f.

- ↑ Charlotte Schubert : Solon. UTB Profile, Tübingen / Basel 2012, p. 45.

- ↑ The existence of the hectemorier has recently been questioned by Mischa Meier : The Athenian hectemoroi - an invention? In: Historische Zeitschrift Volume 294, 2012, pp. 1–29.

- ^ Karl-Wilhelm Welwei: Athens. From the beginning to Hellenism. Vol. 1: Athens. From the Neolithic settlement to the archaic Greater Polis. Bibliographically updated one-volume edition, Darmstadt 2011 (original edition 1992), p. 161 f.

- ↑ Solon, Fragment 5, 5-6 (West); Christoph Mülke (Ed.): Solon's political elegies and Iamben (Fr. 1–13; 32–37 West). Introduction, text, translation, commentary. Munich / Leipzig 2002, p. 49.

- ^ Karl-Wilhelm Welwei: Athens. From the beginning to Hellenism. Vol. 1: Athens. From the Neolithic settlement to the archaic Greater Polis. Bibliographically updated one-volume edition, Darmstadt 2011 (original edition 1992), p. 163.

- ↑ Michael Stahl : Aristocrats and Tyrants in Archaic Athens. Investigations into tradition, social structure and the formation of the state. Wiesbaden 1987, p. 194 f.

- ↑ Aristotle: The State of the Athenians. Translated and explained by Mortimer Chambers. Darmstadt 1990, p. 167. Chambers also deals with the Kyrbeis created with a similar function.

- ↑ Pavel Oliva: Solon - legend and reality. Konstanz 1988, p. 61.

- ^ Karl-Wilhelm Welwei: Athens. From the beginning to Hellenism. Vol. 1: Athens. From the Neolithic settlement to the archaic Greater Polis. Bibliographically updated one-volume edition, Darmstadt 2011 (original edition 1992), p. 166.

- ^ Karl-Wilhelm Welwei: Athens. From the beginning to Hellenism. Vol. 1: Athens. From the Neolithic settlement to the archaic Greater Polis. Bibliographically updated one-volume edition, Darmstadt 2011 (original edition 1992), p. 176 f.

- ↑ Herodotus, Histories 1.29.

- ↑ John Lewis: Solon the Thinker. Political Thought in Archaic Athens. London 2006, p. 124.

- ↑ Pavel Oliva: Solon - legend and reality. Konstanz 1988, p. 56. Welwei points out that there are no instructions in the traditional Solonic statutes for recording the annual income of Athenian citizens, and does not see any need for this under the circumstances at that time. ( Karl-Wilhelm Welwei : Athens. From the Beginnings to Hellenism. Vol. 1: Athens. From Neolithic Settlements to Archaic Greater Polis. Bibliographically updated one-volume edition, Darmstadt 2011 (original edition 1992), pp. 182-184)

- ↑ The existence of the pentakosiomedimnoi as a separate asset class at the time of Solon is strongly doubted by Kurt Raaflaub , who only introduced it in the course of the establishment of developed Attic democracy around the middle of the 5th century BC. ( Athenian and Spartanian Eunomia, or: what to do with Solons Timocracy? In: Josine Blok, André PMH Lardinois (Ed.): Solon of Athens. New Historical and Philological Approaches. Leiden / Boston 2006, p. 408, 415-417).

- ↑ Aristotle: The State of the Athenians. Translated and explained by Mortimer Chambers. Darmstadt 1990, p. 170.

- ↑ Aristotle: The State of the Athenians. Translated and explained by Mortimer Chambers. Darmstadt 1990, p. 178; Charlotte Schubert: Solon. UTB Profile, Tübingen / Basel 2012, p. 62 f .; Karl-Wilhelm Welwei: Athens. From the beginning to Hellenism. Vol. 1: Athens. From the Neolithic settlement to the archaic Greater Polis. Bibliographically updated one-volume edition, Darmstadt 2011 (original edition 1992), pp. 190–192; Pavel Oliva: Solon - legend and reality. Konstanz 1988, p. 57 f.

- ^ Phillip V. Stanley: The economic reforms of Solon. St. Katharinen 1999, p. 255.

- ^ Herodotus, Historien 2.177.

- ↑ Charlotte Schubert: Solon. UTB Profile, Tübingen / Basel 2012, p. 26 f.

- ^ Karl-Wilhelm Welwei: Athens. From the beginning to Hellenism. Vol. 1: Athens. From the Neolithic settlement to the archaic Greater Polis. Bibliographically updated one-volume edition, Darmstadt 2011 (original edition 1992), p. 201.

- ↑ Solon, Fragment 34, 4-9 (West); Christoph Mülke (Ed.): Solon's political elegies and Iamben (Fr. 1–13; 32–37 West). Introduction, text, translation, commentary. Munich / Leipzig 2002, p. 65.

- ↑ Plato, Timaeus 20d; quoted from Charlotte Schubert: Solon. UTB Profile, Tübingen / Basel 2012, p. 73.

- ↑ Solon, Fragment 33, 1-4 (West); Christoph Mülke (Ed.): Solon's political elegies and Iamben (Fr. 1–13; 32–37 West). Introduction, text, translation, commentary. Munich / Leipzig 2002, p. 339.

- ↑ Solon, Fragment 33, 5-7 (West); Christoph Mülke (Ed.): Solon's political elegies and Iamben (Fr. 1–13; 32–37 West). Introduction, text, translation, commentary. Munich / Leipzig 2002, p. 63 and explanatory ibid p. 349.

- ↑ Solon, Fragment 11, 1-8 (West); Christoph Mülke (Ed.): Solon's political elegies and Iamben (Fr. 1–13; 32–37 West). Introduction, text, translation, commentary. Munich / Leipzig 2002, pp. 52–55.

- ↑ Solon, Fragment 9, 1-6 (West); Christoph Mülke (Ed.): Solon's political elegies and Iamben (Fr. 1–13; 32–37 West). Introduction, text, translation, commentary. Munich / Leipzig 2002, pp. 50–53.

- ↑ John Lewis says: “As a sophos , Solon's ability to see the deeper implications of a situation, and thus to avoid long-term harm and attain long-term victory, is his primary claim to virtue over both the potential tyrant and the witting supporters. Solon demonstrates his wisdom by claiming to peer inside the would-be tyrant's noos , the deeper, unseen cause of tyranny. His own purported interchange with a critic recreates the hidden, yet essential difference, between the lawgiver and the tyrant: the tyrant's concern is for the power or loot of the moment, while the lawgiver's focus is long range, which is reflected in the later tradition that he swore his fellows to live by the laws for years into the future "(John Lewis: Solon the Thinker. Political Thought in Archaic Athens. London 2006, p. 35).

- ↑ εἰ .DELTA..di-elect cons γῆς ἐφεισάμην / πάτρίδος, τυραννίδος δὲ καὶ βίης ἀμειλίχου / οὐ καθηψάμην μιάνας καὶ καταισχύνας κλεός / οὐδὲν αἰδέομαι · πλεόν γὰρ ὧδε νικήσειν δωκέω / πάντας ἀνθρώπους (Solon, Fragment 32, 1-5 (West); Christoph Mülke (eds .): Solon's political elegies and Iamben (Fr. 1–13; 32–37 West). Introduction, text, translation, commentary. Munich / Leipzig 2002, pp. 62 f.).

- ↑ Charlotte Schubert: Solon. UTB Profile, Tübingen / Basel 2012, p. 88.

- ↑ Herodotus, Historien 2.177.2; quoted from Charlotte Schubert: Solon. UTB Profile, Tübingen / Basel 2012, p. 44.

- ↑ Plato, Timaeus 20d – 25e; Plutarch, Solon 26; Oliva shows skepticism regarding the Solonic part in the spread of the Atlantis myth. He is not convinced by Plato's sole reference (Pavel Oliva: Solon - Legende und Reality. Konstanz 1988, p. 83).

- ↑ Plutarch, Solon 26.6; quoted from Charlotte Schubert: Solon. UTB Profile, Tübingen / Basel 2012, p. 89.

- ↑ Plutarch, Solon 27: 1; quoted from Pavel Oliva: Solon - legend and reality. Konstanz 1988, p. 13.

- ↑ Aristotle: The State of the Athenians. Translated and explained by Mortimer Chambers. Darmstadt 1990, p. 191.

- ↑ Herodotus, Histories 30–32; Plutarch, Solon 27; Schubert comments: “Solon's encounter with Kroisos and the conversations held at this meeting are a focus for Herodotus, on the basis of which he explains to his readers fundamental considerations about life and death, wisdom and delusion. The fact that he puts it in Solon's mouth of all people can only be explained by the special importance that was attributed to Solon as early as the 5th century - this is how the most powerful and the wisest meet ”(Charlotte Schubert: Solon. UTB Profile, Tübingen / Basel 2012, p. 76).

- ^ Herodotus, Historien 86 f .; Pavel Oliva: Solon - legend and reality. Konstanz 1988, p. 11 f .; Charlotte Schubert: Solon. UTB Profile, Tübingen / Basel 2012, pp. 76–78.

- ↑ Plutarch, Solon 28.

- ↑ Plutarch, Solon 30 f.

- ↑ Plutarch, Solon 32.

- ↑ John Lewis: Solon the Thinker. Political Thought in Archaic Athens. London 2006, p. 1.

- ↑ Σόλων ᾿Εξηκεστίδου Ἀθηναῖος ἔφη (Solon, son of Exekestides, said from Athens)

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios 1.63

- ^ Translation by Bruno Snell

- ^ Samuel Singer : Thesaurus proverbiorum medii aevi. Volume 11. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin et al. 2001, ISBN 978-3-110-16951-5 , p. 69 for the ancient Greek original ( limited preview in the Google book search).

- ↑ ἀφ᾽ ἧς ἀρχὴ δημοκρατίας ἐγένετο . Quoted from: Aristotle: The State of Athens. Translated and explained by Mortimer Chambers. Darmstadt 1990, p. 96.

- ↑ Christian Meier: Origin and special features of the Greek democracy. In Konrad Kinzl (ed.): Demokratie. The way to democracy among the Greeks. Darmstadt 1995. p. 276.

- ^ Karl-Wilhelm Welwei: Athens. From the beginning to Hellenism. Vol. 1: Athens. From the Neolithic settlement to the archaic Greater Polis. Bibliographically updated one-volume edition, Darmstadt 2011 (original edition 1992), p. 206.

- ^ Christian Meier: Origin of the term> democracy <. Four prolegomena to one historical theory. Frankfurt am Main 1970, p. 59.

- ^ Karl-Wilhelm Welwei: Athens. From the beginning to Hellenism. Vol. 1: Athens. From the Neolithic settlement to the archaic Greater Polis. Bibliographically updated one-volume edition, Darmstadt 2011 (original edition 1992), p. 178.

- ^ Karl-Wilhelm Welwei: Athens. From the beginning to Hellenism. Vol. 1: Athens. From the Neolithic settlement to the archaic Greater Polis. Bibliographically updated one-volume edition, Darmstadt 2011 (original edition 1992), p. 169 f.

- ↑ Pavel Oliva: Solon - legend and reality. Konstanz 1988, p. 81.

- ↑ Charlotte Schubert: Solon. UTB Profile, Tübingen / Basel 2012, p. 65 f.

- ^ Hans-Joachim Gehrke: The figure of Solon in the Athênaiôn Politeia. In: Josine Blok, André PMH Lardinois (ed.): Solon of Athens. New Historical and Philological Approaches. Leiden / Boston 2006, p. 279.

- ↑ Pavel Oliva: Solon - legend and reality. Konstanz 1988, p. 82 f.

- ↑ Michael Stahl: Solon F 3D. The birth of the democratic idea. In: Gymnasium. Volume 99, 1992, p. 400 f.

- ^ Kurt Raaflaub: Introduction and balance sheet. In Konrad Kinzl (ed.): Demokratie. The way to democracy among the Greeks. Darmstadt 1995, pp. 25-52.

- ^ "In many respects Solon and his associates, who helped to formulate these reforms, did more than any other individuals to advance an determine the economic development of Athens over the next several centuries" (Phillip V. Stanley: The economic reforms of Solon. St. Katharinen 1999, p. 298 f.).

- ↑ Michael Stahl: Solon F 3D. The birth of the democratic idea. In: Gymnasium. Volume 99, 1992, p. 406.

- ↑ Michael Grant: Classics of Ancient Historiography. Munich 1981, pp. 32-64; especially p. 52 and 61.

- ^ Problem description in Chambers, p. 76 f. (Aristotle: The State of Athens. Translated and explained by Mortimer Chambers. Darmstadt 1990.).

- ↑ Aristotle: The State of the Athenians. Translated and explained by Mortimer Chambers. Darmstadt 1990, p. 159.

- ↑ Aristotle: The State of the Athenians. Translated and explained by Mortimer Chambers. Darmstadt 1990, p. 175.

- ^ Hans-Joachim Gehrke: The figure of Solon in the Athênaiôn Politeia. In: Josine Blok, André PMH Lardinois (ed.): Solon of Athens. New Historical and Philological Approaches. Leiden / Boston 2006, pp. 284–286.

- ↑ Michael Grant: Classics of Ancient Historiography. Munich 1981, pp. 266-269.

- ↑ Michael Grant: Classics of Ancient Historiography. Munich 1981, p. 274.

- ↑ Lukas de Blois: Plutarch's Solon: a tissue of commonplaces or a historical account? In: Josine Blok, André PMH Lardinois (ed.): Solon of Athens. New Historical and Philological Approaches. Leiden / Boston 2006, p. 429 f.

- ↑ "... he undoubtly used factual information that he found in his sources in a quite scrupulous way, as he always did" (Lukas de Blois: Plutarch's Solon: a tissue of commonplaces or a historical account? In: Josine Blok, André PMH Lardinois (Ed.): Solon of Athens. New Historical and Philological Approaches. Leiden / Boston 2006, p. 437).

- ↑ Michael Stahl: Aristocrats and Tyrants in Archaic Athens. Investigations into tradition, social structure and the formation of the state. Wiesbaden 1987, p. 231.

- ^ Fabienne Blaise: Poetics and politics: tradition re-worked in Solon's 'Eunomia' (Poem 4). In: Josine Blok, André PMH Lardinois (ed.): Solon of Athens. New Historical and Philological Approaches. Leiden / Boston 2006, p. 129.

- ^ André PMH Lardinois: Have we Solon's verses? In: Josine Blok, André PMH Lardinois (ed.): Solon of Athens. New Historical and Philological Approaches. Leiden / Boston 2006, p. 33.

- ^ Eva Stehle: Solon's self-reflexive political persona and its audience. In: Josine Blok, André PMH Lardinois (ed.): Solon of Athens. New Historical and Philological Approaches. Leiden / Boston 2006, p. 110 f.

- ^ Fabienne Blaise: Poetics and politics: tradition re-worked in Solon's 'Eunomia' (Poem 4). In: Josine Blok, André PMH Lardinois (ed.): Solon of Athens. New Historical and Philological Approaches. Leiden / Boston 2006, p. 130 f.

- ↑ Eberhard Ruschenbusch: ΣΟΛΩΝΟΣ ΝΟΜOI. The fragments of the Solonic legal framework with a text and tradition history. Historia individual writings Vol. 9, Wiesbaden 1966.

- ↑ Adele C. Scafuro: Identifying Solonian laws. In: Josine Blok, André PMH Lardinois (ed.): Solon of Athens. New Historical and Philological Approaches. Leiden / Boston 2006, p. 179.

- ^ PJ Rhodes: The reforms and laws of Solon: an optimistic view. In: Josine Blok, André PMH Lardinois (ed.): Solon of Athens. New Historical and Philological Approaches. Leiden / Boston 2006, p. 257.

- ↑ John Lewis: Solon the Thinker. Political Thought in Archaic Athens. London 2006, p. 23.

- ↑ John Lewis: Solon the Thinker. Political Thought in Archaic Athens. London 2006, p. 31.

- ↑ John Lewis: Solon the Thinker. Political Thought in Archaic Athens. London 2006, p. 39 f.

- ↑ John Lewis: Solon the Thinker. Political Thought in Archaic Athens. London 2006, pp. 128-130.

- ↑ Joseph Almeida: Justice as an aspect of the polis idea in Solon's political poems: a reading of fragments in light of the researches of new classical archeology. Leiden and Boston 2003, p. 239.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Solon |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Greek politician and legislator of Athens |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 640 BC Chr. |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Athens |

| DATE OF DEATH | around 560 BC Chr. |