Demosthenes

Demosthenes ( Greek Δημοσθένης Dēmosthénēs , Latin and German Demósthenes; * 384 BC ; † 322 BC in Kalaureia ) was one of the most important Greek speakers . After the Peace of Philocrates in 346 BC BC he rose to the leading statesman of Athens . He held this position until the Harpalos affair in 324 BC. Claim.

Life

Childhood, adolescence and years of education (384–354)

At the age of seven Demosthenes lost his father, a wealthy sword and furniture manufacturer of the same name, who left him some ergasteries with 30 slaves. Until he came of age, he was under the tutelage of three relatives determined by his father's will, Aphobos, Demophon and Therippides, who in Demosthenes' eyes poorly managed the property and ran large parts of it. It was his mother Cleobule alone who raised him with care and provided him with a thorough education.

The experience may have caused him to learn the art of speaking. Different personalities are handed down as his teachers. According to Cicero , Quintilian and Hermippus , he was an apprentice to Plato. Lukian counts Aristotle , Theophrast and Xenocrates among his teachers. In general, according to Plutarch , one sees in Isaios , a speaker who probably specializes in inheritance law, the teacher of the young Demosthenes.

His weak voice and constitution, which did not predestine him to be a speaker and earned him the nickname Βάταλος ("sissy, weakling"), he overcame through persistent training (for example by reading long texts with pebbles in his mouth) at least for prepared speeches, in unprepared ones On the other hand, he retained his oratorial weakness in speeches.

At the age of twenty he accused the administrators of his inheritance of embezzlement and obtained the conviction of one guardian. In the other two cases a comparison was probably made. In total, he was only able to regain part of the lost inheritance. His speech Against Aphobos has survived , which contains numerous details on the creation of value and production of Attic ergasteries as well as on asset management in the 4th century BC. Supplies.

He then used the knowledge he had gained to offer himself to young men in a similar situation as logographers .

Political activity until the death of King Philip of Macedon (354–336)

In 354, the 30-year-old Demosthenes spoke for the first time on a matter that concerned the state - in the speech on symmories . Before that, in his speech Against Androtion and in other subsequent political trials, he appeared as a follower of Eubulus . Later he changed sides and, in view of the growing power of Philip II of Macedonia , demanded in 348 BC. In his 3rd Olympic speech , he said that surplus funds would no longer be sent to the citizens via the cash register for theater money, but would be used for military purposes. 346 BC He belonged with Philocrates and Aeschines to the ten-member Athens delegation that concluded a peace treaty with Philip in Pella . Demosthenes also advocated this treaty in his peace speech, but later sued his followers - including Hypereides - their emissaries, above all Aeschines.

Raised to the leading statesman of Athens, Demosthenes forged an alliance against Philip. This alliance was subject to Philip in 338 BC. At the battle of Chaeronea . Nevertheless Demosthenes was able to maintain his position.

Political activity under the rule of Alexander the Great (336–322)

330 BC He won as defender of the Ctesiphon , the 336 BC. BC Demosthenes had applied for the wreath to the Dionysia in the theater and against the Aeschines therefore a γραφὴ παρανόμων graphḗ paranómōn ("complaint against unlawful laws or decisions"), a spectacular trial against Aeschines as the accuser. The speeches against Ctesiphon by Aeschines and For Ctesiphon by Demosthenes (18th speech, also called wreath speech) held in this process were considered masterpieces of rhetoric in antiquity.

324 BC The treasurer of Alexander the great , Harpalus , fled to Athens. After he was arrested, an investigation revealed that some of the funds he had brought with him were missing. The Areiopag , who was commissioned with the investigation of Demosthenes himself, announced as a result that Demosthenes had received 20 talents for helping people escape . Hypereides used this to overthrow Demosthenes, who was subsequently sentenced to 50 talents and was imprisoned for insolvency, from which he escaped.

End of life (322)

After the death of Alexander (323 BC), who had lived since 336 BC After he had demanded his extradition, Demosthenes returned from exile and once again supported the anti-Macedonian party. When Athens against the Macedonian governor Antipater in the Lamian War of 322 BC. After a short escape, Demosthenes took his own life to avoid imminent arrest.

Works

61 speeches, 6 letters and 56 prooimies (here: building blocks for speeches) are preserved under the name Demosthenes:

Speeches to the People's Assembly (1–17)

In his first speech to the People's Assembly, On the Symmories (14th), Demosthenes suggests that the law on tax cooperatives should be made more effective. In addition, he fights (still in the spirit of Eubulus) against a war hysteria fueled with the warning of alleged Persian armor.

Since the change in foreign policy, for which Isocrates campaigned about two decades earlier with the Plataikos and the speech of Archidamos , Athens and Sparta were repeatedly linked, while the smaller Peloponnesian states sought protection from Sparta at Thebes. In his speech On the Megalopolitans (16.) Demosthenes tries to break up these structures. This is the first step towards the alliance with Thebes, which finally came about before Chaironeia.

In the speech for the freedom of the Rhodians (15th) Demosthenes calls for support for the displaced Rhodian democrats and conjures up old confederation fantasies.

The collection of speeches against Philip (1–12)

The first speech against Philip (4th) was perhaps written before the speech for the freedom of the Rhodians . Since the whole picture of Demosthenes depends on it, this question is hotly contested in literature.

The Olynthian speeches (1st – 3rd) were written in 349. The dispute over the use of the theater money is the main theme in them, alongside the call to fight against Philip.

In his speech On Peace (5th), Demosthenes condemns the Peace of Philocrates, which was concluded in 346, but calls on him to adhere to its provisions until new allies have been found.

The second speech against Philip (6th) is a report on a legation trip to Messene and Argos, two states that sought protection from Thebes and Sparta with Philip.

343 BC BC Athens had sent a group of colonists to the Chersonese peninsula. In doing so, they got into conflicts with the local population, in which Philip interfered. Thereupon some wanted to recall the leader of the colonists, Diopeithes, and bring him to court in Athens and thus keep the peace with Philip. Demosthenes opposed this in his speech on the affairs of Chersonese (8th).

The speech about Halonnesus (7th) comes from Hegesippos, the 11th speech of Philip's letter and the answer in the 12th speech come from the Philippica of Anaximenes by Lampsakos .

The third speech against Philip (9th) is the most passionate, most hateful. The final part of the fourth speech against Philip (10th) largely corresponds to the Chersonese speech . The possibility, discussed in the middle section, of being supported by the Persians in the fight against Philip is remarkable.

Speeches from Trials of Illegal Motions (18–26)

Demosthenes held the speech against Leptines (20th) in 355 BC. For the son of Chabrias, who fell two years earlier . Chabrias was awarded the Atelie , freedom from taxes for himself and his descendants. Leptines had prevailed following law: "No one shall have the Atelie, except for the descendants of Tyrannicides Harmodios and Aristogeiton, nor shall it henceforth allowed to give be the same." (160) He was accused of an illegal request to have asked. - Demosthenes 'speech contains clever political philosophical considerations: Lepines' law curtails the rights of the people by prohibiting the granting of an atelie also in the future. With the award of the studio one has entered into a commitment. Here Demosthenes recalls that the restored democracy repaid the debts that the thirty took on with the Spartans to fight the democrats (11 ff.).

The speeches Against Androtion (22nd) and Against Timocrates (24th) were given by Diodorus, a common citizen. As a speechwriter, Demosthenes had the task of putting words into his mouth that would distract from the people behind the complaints and make them appear as private vengeance. The common man from the people was supposed to anger the judges for alleged abuses by Androtion in the collection of taxes and thus achieve the condemnation of Androtion and Timocrates (who had campaigned for Androtion with a bill).

Aristocrates had introduced a law: "If someone kills the Charidemos, he should be able to be apprehended everywhere in the state." (16) The so protected was a cunning mercenary leader who had usurped power in Thrace. - The speech against Aristocrates (23rd) is intended to show that Aristocrates' proposal is illegal and detrimental to the state. In addition, Charidemos is unworthy of such an honor. As regards the first point, he gives a detailed account of the laws and courts responsible for all possible cases of violent death (19–99, here he gives a whole legal handbook!); secondly, a criticism of Athens' policy in northern Greece (100-143) and thirdly, a story of the breaches of faith and betrayals by Charidemos (148-183). At the end there is a failure against enriching politicians that does not match the previous, factual style of speech.

Against Meidias (21st) is a draft of a speech that was probably published from the estate and was never given. The rich and powerful Meidias had Demosthenes, who in 348 BC Chr. Chorege at the Dionysia was struck on the stage of the theater!

The speeches about the “false embassy” (19th) and For Ctesiphon (18th, wreath speech) are directed against Aeschines .

Speeches from private trials (27–59)

Guardianship processes (27–31)

The speech against Aphobus I (27.) contains the guardianship account with which Demosthenes tries to prove the fraud allegedly committed against him. In Gegen Aphobos II (28) he reports on an anti-dose procedure that was supposed to deprive him of his claims.

From the two speeches against Onetor (30th and 31st) it emerges that Demosthenes won the trial against Aphobos, but still did not (or at least not immediately and in full) received this money. Even before the trial against Aphobos was decided, Aphobos divorced, and when Demosthenes wanted to seize his property after the verdict, his former brother-in-law, the extremely wealthy Onetor, came before him. He claimed that he was entitled to the property because Aphobos had to repay the dowry after the divorce. Demosthenes, on the other hand, tries to show that in reality there was no divorce at all.

The dispute over the legacy of the banker Pasion (36 and 45)

Demosthenes wrote, probably 350 BC. Chr., The speech Für Phormion (36.), for a former slave from Pasion, who according to a testamentary decree had married his widow and continued the business. The opponent in this process was Pasion's son Apollodorus .

A year later, Apollodoros accused Stephanos of having given false testimony in the Phormion trial; Demosthenes wrote this speech ( Against Stephanos [45.]). The reason for this unusual change to the counterparty was probably that Apollodoros, as a member of the council, had taken the risk of applying for the money to be used for war purposes.

On the basis of this one speech, six other speeches given by Apollodorus and written by him or an unknown logographer have been preserved in the collection of Demosthenes speeches.

More speeches from private trials

In counter Zenothemis (32) is about fraudsters sold the same shipment twice and to not be discovered, hit a hole in the ship's side.

When reviewing the citizen's role, Eubulides, as head of the village of Halimus, had Euxitheos deleted. This is why he accuses him in Gegen Eubulides (57th): Eubulides wanted to take revenge on him because with his testimony he caused that he was defeated in another trial.

Official speeches (60 and 61)

The ancient Demosthenes editor (presumably Callimachos ) wanted to round off the collection with a few pomp or ceremonial speeches in addition to the advisory speeches and court speeches. The Erotikos (61st) certainly does not come from Demosthenes, while the Ephitaphios (60th) perhaps actually dates from 338 BC. By Demosthenes for those who fell at Chaironeia .

Survival

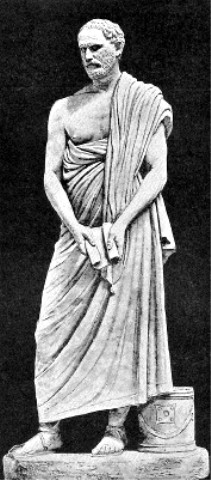

280 BC BC, 42 years after his death, a portrait statue of the speaker was publicly displayed in Athens, which has been handed down in several Roman copies. Because of its reliable dating, it is considered the main work of early Hellenistic sculpture .

Cicero held Demosthenes in high esteem. He planned a translation of the wreath speech, and an introduction has been received. He called his speeches against Mark Antony , following Demosthenes' example, Philippine speeches . After that, the term “Philippika” became a winged word .

In 1470 Cardinal Bessarion published the First Olynthian Speech to call for a fight against the Turks. Niebuhr translated the First Speech against Philip to fuel the fight against Napoleon.

At the latest after the publication of Droysen's biography of Alexander (1833), voices rose against the view of Demosthenes as a fighter for freedom , which saw in his struggle a hopeless resistance to the unification of Greece.

The American presidential candidate of 1872 Victoria Woodhull relied on their visions regarding the ancient Greek orator, to emphasize their political beliefs.

expenditure

- Mervin R. Dilts : Demosthenis Orationes . Four volumes, Oxford 2002–2009 (authoritative text edition).

- Demosthenes: Political Speeches . Translated and edited by Wolfhart Unte . Reclam, Stuttgart 2010 (contains speeches 1–10 with the exception of the seventh speech by Hegesippos).

- Demosthenes: Speech for Ctesiphon on the wreath . Explained and provided with an introduction by Hermann Wankel . Winter, Heidelberg 1976, ISBN 3-533-02557-8 and ISBN 3-533-02558-6 (authoritative and comprehensive commentary).

- Demosthenes: Speeches to finance the navy. Against Euergos and Mnesibulos, Against Polykles, Over the trierarchical wreath. Edited, introduced and translated by Christos Karvounis . Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2007, ISBN 978-3-534-19347-9 .

- Demosthenes: Selected Speeches . Translated into German by Prof. A. Westermann. Langenscheidtsche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Berlin 1855–1911.

- Demosthenes: speech about the crown . Translated by Friedrich Jacobs. Edited by Dr. Max Oberbreyer. Leipzig 1877 (nicer translation of the wreath speech).

- Dieter Irmer : Demosthenes 54, 11-12: a medical "report" , Medizinhistorisches Journal 2 (1967), pp. 54-62.

literature

Overview display

- Evangelos Alexiou: Demosthenes. In: Bernhard Zimmermann , Antonios Rengakos (Hrsg.): Handbook of the Greek literature of antiquity. Volume 2: The Literature of the Classical and Hellenistic Period. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-61818-5 , pp. 799-825

Overall presentations and investigations

- Christos Karvounis: Demosthenes. Studies on his demegories orr. XIV, XVI, XV, IV, I, II, III (= Classica Monacensia. Volume 24). Gunter Narr Verlag, Tübingen 2002, ISBN 3-823-34883-3 (dissertation).

- Gustav Adolf Lehmann : Demosthenes of Athens. A life for freedom. Beck, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-406-51607-6

- Iris Samotta: Demosthenes. Francke, Tübingen 2010, ISBN 978-3-8252-3407-2 .

- Raphael Sealey: Demosthenes and his time. A study in defeat , Oxford University Press, New York 1993, ISBN 0-19-507928-0 .

- Julia Witte: Demosthenes and the Patrios Politeia. From the imaginary constitution to the political idea. Habelt, Bonn 1995, ISBN 3-7749-2706-5 .

- Ian Worthington (Ed.): Demosthenes. Routledge, London / New York 2000, ISBN 0-415-20456-9 .

- Ian Worthington: Demosthenes of Athens and the Fall of Classical Greece. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2013, ISBN 978-0-19-993195-8 ( review in Bryn Mawr Classical Review ; review in sehepunkte ).

reception

- Bernhard Huss : Demosthenes. In: Peter von Möllendorff , Annette Simonis, Linda Simonis (ed.): Historical figures of antiquity. Reception in literature, art and music (= Der Neue Pauly . Supplements. Volume 8). Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2013, ISBN 978-3-476-02468-8 , Sp. 351-360.

Web links

- Literature by and about Demosthenes in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Demosthenes in the German Digital Library

- Demosthenes' works in English translation

- Demosthenis Oratorum Graeciae principis Opera, quae ad nostram aetatem peruenerunt, omnia: in quinq [ue] divisa partes ... / unà cum Vlpiani Rhetoris Commentarijs, È Graeco in Latinum sermonem conuersa, per Hieronymvm VVolfivm Oetingensem. - Basileae: Oporinus, 1549. Digitized edition of the University and State Library Düsseldorf (5 volumes)

Remarks

- ↑ Cicero, Brutus 35; Quintilian, Institutiones 10, 1, 6. 76; in Plutarch, Demosthenes 5.

- ↑ Lukian, Praise of Demosthenes 12.

- ↑ Plutarch, Demosthenes 5.

- ↑ ZEIT online : Biography: The power of the word

- ↑ Plutarch, Demosthenes 4 and 6-8; see also Franz Kiechle : Demosthenes 2). In: The Little Pauly (KlP). Volume 1, Stuttgart 1964, Sp. 1484-1487 (here: Sp. 1484).

- ↑ Reinhard Lullies : Portrait statue of Demosthenes from Polyeuktus . In: Karl Schefold (ed.): The Greeks and their neighbors (= Propylaea art history . Volume 1 ). Propylaeen-Verlag, Berlin 1967, p. 195 Fig. 120 .

- ↑ The church father Hieronymus already used it. - Georg Büchmann : Winged words . The treasure trove of quotations from the German people, collected and explained by Georg Büchmann, continued by (...), reviewed by Alfred Grunow . 31st edition. Haude & Spenersche Verlagbuchhandlung, Berlin 1964, p. 507 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Demosthenes |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Orator of Ancient Greece |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 384 BC Chr. |

| DATE OF DEATH | 322 BC Chr. |

| Place of death | Kalaureia |