Atlantis

Atlantis ( ancient Greek Ἀτλαντὶς νῆσος Atlantìs nḗsos 'island of Atlas ') is a mythical island kingdom that the ancient Greek philosopher Plato (428/427 to 348/347 BC) founded in the middle of the 4th century BC. Chr. Mentioned first and described. According to Plato, it was a naval power that, starting from its main island, “beyond the pillars of Heracles ”, subjugated large parts of Europe and Africa. After a failed attack on Athens , Atlantis was finally around 9600 BC. Chr. As a result of a natural disaster within "a single day and an unfortunate night" set.

Atlantis is a story embedded in Plato's work, which - like the other myths of Plato - is intended to illustrate a previously established theory. The background to this story is controversial. While ancient historians and philologists almost without exception assume an invention of Plato that was inspired by contemporary models, some authors suspect a real background of history and made countless attempts to localize Atlantis (see the article Localization Hypotheses on Atlantis ).

A possible existence of Atlantis was already discussed in ancient times . While authors like Pliny denied that the island kingdom in question existed, others, such as Krantor , Poseidonios or Strabo , considered its existence to be conceivable. The first parodies of the topic also originated in antiquity.

In the Latin Middle Ages , the myth of Atlantis was more or less forgotten until it was finally rediscovered and spread during the Renaissance , when scholars in Europe now understood Greek again. Plato's descriptions inspired the utopian works of various early modern authors, such as Francis Bacon's Nova Atlantis . To this day, the literary motif of the Atlantis myth is processed in literature and film (see the article Atlantis as a subject ).

Description of Plato

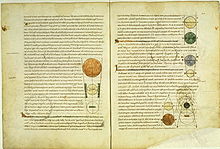

Plato describes the island of Atlantis in his 360 BC. Timaeus and Critias wrote dialogues . The Critias remained unfinished. In these works the author lets the two politicians Critias and Hermocrates as well as the philosophers Socrates and Timaeus meet and discuss. Even if these are historical persons (although only the first three are documented), the conversations Plato ascribed to them are fictional . The Socratic dialogue is used here as a rhetorical figure and is intended to convincingly convey Plato's doctrinal statements by not dictating dogmatically , but developing them dialectically in front of the reader's eyes . While the subject of Atlantis is only touched upon briefly in Timaeus , a detailed description of the island kingdom follows in Kritias .

The two Atlantis dialogues Timaeus and Critias are only parts of an initially apparently more extensive plan. The Dialogue Timaeus follows directly on from the Dialogue Politeia , the results of which he recapitulates. The short Critias breaks off unfinished and Plato did not even begin the dialogue of Hermocrates announced in the Timaeus . Plutarch gave the reason for this that Plato died before finishing his work because of his old age. The last dialogue in this series can be considered the nomoi , in which the end of the last natural catastrophe in the sense of Timaeus and Critias is chosen as the starting point for the discussion.

Origin of the Atlantis tradition

A wish expressed by Socrates to see the advantages of a city-state of this type in reality and specifically to examine its probation in the event of war is linked to the presentation of the main features of the Platonic ideal state of the Politeia in the first part of the Timaeus (Tim. 17a– 20c). Critias then tells a story about which he claims that his grandfather told him in his youth (Tim. 20d ff.). The grandfather in turn heard them from the famous legislator Solon , with whom his father Dropides ("Dropides II.") Was friends. Solon brought the news of Atlantis with him from Egypt , where he learned it in Sais from a priest of the goddess Neith (Tim. 23e). This priest had translated the messages for him from “holy scriptures”. At several points in the narrative, Plato lets Critias emphasize that his story was not invented, but actually happened that way (Tim. 20d, 21d, 26e).

Framework of the Atlantis tradition

The content of the story, which Kritias remembers, is one of the allegedly “greatest heroic deeds of Athens”, namely the defense against a huge army of the expansive sea power Atlantis. That island kingdom, which like Athens already existed 1000 years before the founding of Egypt (Timaeus 23d – e), is said to have ruled many islands and parts of the mainland, Europe to Tyrrhenia and Libya (North Africa) to Egypt and was about to be Subjugate Greece (Timaeus 25a – b). After the attack was fended off by the Athenians, who were outstanding in courage and martial arts, first as the leading state of the Hellenes, then fighting alone after the others had defected, the "entire warring sex" of the Atlanteans was closed for one day and one night due to severe earthquakes and floods most of them died and Atlantis sank in the sea due to earthquakes (Timaeus 25c – d; Critias 108e). Only Egypt, which was founded 8,000 years before Solon and where the tradition of Athens' heroism comes from (Timaeus 23d – e; Critias 108e, 109d ff., 113a), was spared.

Atlantis

In Critias , Plato describes Atlantis in detail: It was an empire larger than Libya (Λιβύη) and Asia (Ασία) combined (Timaeus 24e). In Plato's time, these terms were understood to mean North Africa without Egypt and the parts of the Near East that were known at the time. The main island was outside the " Pillars of Heracles " in the Atlantìs thálassa , as Herodotus calls the Atlantic (Herodotus I 202,4). The "island of Atlas" was loud Plato rich in natural resources of all kinds, especially gold, silver and " Oriharukon ", a first in the Hesiod attributed Epyllion called "metal" that Plato as "fiery shimmering" "Shield of Hercules" describes (Critias 114e). Plato also mentions various trees, plants, fruits and animals, including the "largest and most voracious animal of all", the elephant (Kritias 115a). The wide plains of the large islands were extremely fertile, precisely parceled out and supplied with sufficient water through artificial canals. By using the rain in winter and the water from the canals in summer, two harvests per year were possible (Kritias 118c – e).

The middle of the main island formed a 3000 by 2000 stadium large plain. A Greek “stadium” is around 180 meters, an Egyptian “stadium” around 211 meters, so it is around 400 to 600 kilometers. This plain was surrounded and traversed by right-angled canals, resulting in a large number of small inland islands. The acropolis of the capital was five stadiums wide and built on a mountain that lay in the center of the island. Around this acropolis there were three ring-shaped canals connected to the sea by a wide canal. The inner artificial water belt was one stadium wide, followed by two pairs of concentric land and water belts two and three stadia wide respectively (Kritias 115d – 116a). Plato describes the two outer canals as navigable.

In the center of Atlantis, according to the dialogues, there was a Poseidon temple on the Acropolis , which Plato called "a stadium long, three plethra (that is about 60 m) wide and of a corresponding height" and inside and outside with gold, silver and ore alcalos described exaggerated. There were gold consecration statues around the temple. A cult image showed the god of the sea as the driver of a six-horse chariot (Kritias 116d – e). There was a hippodrome near the central complex . The rulers' homes were also located in the innermost district, which was enclosed by a wall. The ring-shaped outskirts of the city housed the quarters of the guards, the warriors and the citizens from the inside out. The entire complex was enclosed by three further, concentrically arranged circular walls (Kritias 116a – c). The two outermost canals were built as harbors, with the inner canal serving as a naval port and the outer one as a trading port (Kritias 117d – e).

Poseidon had transferred power over the island to his son Atlas , fathered with the mortal Kleito , who was the eldest of his descendants from five pairs of twins (Kritias 114a – c). Atlas and his descendants ruled the capital; the lines of his younger brothers ruled the other parts of the empire. Over time, Atlantis changed from an originally rural island to a powerful sea power through ever more extensive construction measures and upgrades. The descendants of Atlas and his siblings had a unique army and a strong navy with 1,200 warships and a crew of 240,000 for the capital's fleet alone (Kritias 119a – b). With this force they subjugated Europe to Tyrrhenia and North Africa to Egypt (Timaeus 24e – 25b). Only the numerically outnumbered Athenians were able to bring this advance to a standstill.

This military defeat of Atlantis is portrayed as a punishment from the gods for the hubris of his rulers (Timaeus 24e; Kritias 120e, 121c). Because the "divine part" of the Atlanteans had visibly dwindled through mixing with humans, they were seized by greed for power and wealth (Critias 121a-c). The “Kritias” breaks off before the gods gather for a judgment over the kingdom, at which further punishments should be discussed: “But the god of gods, Zeus , who rules according to the laws and is well able to recognize such, decided, when he saw an excellent generation come down shamefully to inflict punishment on them, (121c) so that they, brought to their senses by it, might return to a nobler way of life. He therefore called all the gods together in their most venerable abode, which lies in the middle of the universe and grants an overview of all things that have ever participated in becoming, and after he had called them together, he spoke ... "

Ur-Athens

In addition to Atlantis, Plato describes the “primordial Athens” in Critias , albeit much shorter. In contrast to the real Athens from Plato's lifetime, ancient Athens is a pure land power that ruled Attica up to the Isthmus of Corinth (Kritias 110e). Although it was close to the coast, it had no ports and, out of a conscious decision, did not operate at sea. Plato's Polis Athens is described as an extremely fertile stretch of land, covered by fields and forests, and "capable of maintaining a large army of those who were freed from the business of agriculture" (Kritias 110e – 111d). The goddess Athena herself founded the political structures and institutions in the city-state named after her, which Plato portrays as almost identical to those of his ideal state described in the Politeia . When Athens was attacked by Atlantis, it was able to repel the attackers and even freed some already subjugated Greek tribes. As the reason why there are no records, stories or legends of the glorious victory over the Atlanteans in ancient Greece, Plato names earthquakes and floods that repeatedly afflicted the ancient Hellenic tribes. But Plato also mentions a very large and particularly devastating flood, which resulted in the fall of the ruling upper class on the coasts. It left only a small portion of the reading and writing behind to ignorant farmers who lived in the mountainous regions. As a result, the entire knowledge that the Greeks had acquired until then was lost.

interpretation

A platonic myth

About the possible historical starting points, e.g. B. the sinking of the Aegean island of Santorini in the 17th or 16th century BC. BC (see Minoan eruption ), scientific agreement can hardly be achieved at the moment. On the other hand, there is broad consensus in science about the philological fictional character of the island kingdom of Atlantis. When asked what the message of this story was, there are very different answers. The dialogues Timaeus and Critias are written as a supplement and continuation of the Politeia . The Atlantis story served as a demonstration of the practical proof of the ideal state. It is a Platonic myth and thus only one of many fictional and mythical representations in Plato's works.

Purpose of the myth

According to the prevailing opinion, the purpose of this myth is to raise a previously discussed theory to a practical and illustrative level in order to confirm its functionality and correctness. In this sense, at the end of the Politeia, after the question “What is justice?” Has been discussed, Socrates provides the (apparent) confirmation of his theses by telling the “true” story of the Pamphylian He (Pol. 614b). He saw the underworld in a kind of near-death experience and gained the knowledge that just people would be rewarded tenfold after death, but unjust people were punished tenfold. At a later point, at the end of the ninth book of the Politeia, the question will also be discussed whether a just person should participate in the political life of his city-state. In response to Socrates' answer that the righteous could get involved, but perhaps not in his earthly polis, Glaukon replied that such an ideal state can only be found as a “model” (παράδειγμα) in the “heaven” of ideas to which one can hold (Pol. 592a-b). However, it remains controversial to what extent this allusion could represent an indication of a late practical relevance of the Platonic state philosophy and thus the basis of the Atlantis myth.

In the case of the Atlantis story, it is the theory of the ideal state that needed real confirmation. At the beginning there is Socrates' wish to see the ideal state in the "movement" of a thought experiment. To this end, the myth of the ideal state that once existed in Athens and the powerful opponent Atlantis is invented and put into the mouth of the narrator Kritias, who would have thought of this tradition "in a mysterious way by a kind of chance" on the way home from an earlier philosophical conversation ( Tim.25e). In this passage, Kritias emphasizes that one can adapt the Atlantis material favorably to the theoretical content of the Politeia : “But we want the citizens and the state, which you represented to us yesterday as if fictitious (ὡς ἐν μύθῳ), now into reality ( ἐπὶ τἀληθὲς) and settle here as if that state was the local one, and we will say of the citizens that you thought they were those real ancestors of us, of whom the priest told ” (Tim. 26c-d ). The pseudo-historical tradition is intended to underline the reality that has been claimed several times. Like every Platonic myth, the Atlantis story also claims to be truth, but not in the sense of "historically true or untrue", but in the sense of a philosophical essential truth.

The opponents Athens and Atlantis are ideally constructed as diametrically opposed polities: on the one hand, the small, stable and defensible land power, on the other hand, the sea power that is crumbling due to its urge to expand. This conscious contrast is understood in research as a political allegory of the expansive sea power politics of real Athens. Plato had in 404 BC BC had to witness the defeat of his hometown in the Peloponnesian War , which was once triggered by the hegemony of the Athenians in the Aegean Sea . A few decades later, when Athens had regained part of its former power, the Attic League , which had once been dissolved as a result of the defeat , was re-established - albeit not on the same scale. Plato may have feared that Athens would repeat these mistakes and head for a comparable catastrophe. In order to counteract this and to teach his fellow citizens, Plato is likely to have invented or used the story of the sea power Atlantis, which perished due to expansionism , and the victorious land power Ur-Athens: "He pointed out the dangers that await such an imperialist sea power [...], and he tried, so to speak, to provide quasi-historical proof that a state that was set up like his ideal state would convincingly prove itself in such a situation ”, as Heinz-Günther Nesselrath sums up.

The circumstances that in the Atlantis myth the original Athens is portrayed as being over a thousand years older than Egypt and that the goddess Athene-Neith is said to have established both social systems is interpreted as a reaction of Plato to possible allegations of plagiarism. This has to do with Plato's work on the ideal state - Politeia : a critic of Plato, Isocrates , had written as an immediate reaction to the Politeia a work entitled Busiris , according to which the Egyptian king of the same name - existing only in Greek mythology - in his Country had established a social order that seems to anticipate that of the ideal Platonic state. Plato, according to the theory, has now responded with a myth that the ideal state first existed not in Egypt but in Athens. In addition, with Plato it is precisely the Egyptian priests who bring this knowledge to the Greeks.

Plato's “competition” with Homer can be seen as the reason for the fictitious tradition . Already in the “Politeia” Plato wrote of the “old dispute between poetry and philosophy” (Politeia 607b). In his claim to "replace" the mythical-poetic works of Homer with his own, philosophically thought-out myths such as Atlantis, Plato does not refer to muses like the poet , but to historical traditions (the origin of which, however, is deliberately so far in the dark, that they cannot possibly be verified). In the Timaeus , Kritias speaks of the fact that Solon originally planned to artistically process the subject “Atlantis”, which he heard in Egypt. However, he was prevented from doing so because he was needed as a politician in Athens (although this is not possible chronologically, since Solon only visited Egypt after his “political career”). If he had transformed the Atlantis myth into poetry, Kritias is certain, this work would have far outshone the Homeric epics Iliad and Odyssey (Tim. 21d).

Inspirations and role models

The model for “Ur-Athens” was the ideal state that Plato had designed in his important work Politeia . This already shows the fictional character of the entire story, especially since, according to current knowledge, at no point in Athens - from the early period to the Classical period - did the described combination of political, social and military elements exist. “Ur-Athens” is obviously a creation of Plato. A certain orientation of the land power “Ur-Athens” to the real land power Sparta seems conceivable, although Plato's ideal state does not pursue a sea power policy anyway. The description of the fertile soils of Attica in the times of "Ur-Athens" is based on the assumption that was common in Plato's time that isolated rock massifs such as the Acropolis and Lycabettos were remnants of a former plateau whose "soft" portions of fertile soil have since been washed away by rain and floods be. A comparable theory is based on the localization of Atlantis beyond the "Pillars of Heracles"; in Plato's time - according to the reports in Herodotus (2, 102, 1–2; 4, 43) - it was assumed that the sea beyond the pillars was muddy, viscous and impassable. Plato explains this supposed fact with the sinking of a land mass.

For the antagonist to his ideal state “Ur-Athens”, Plato used real models from his time. It is generally assumed that Atlantis was "put together" by him like a mosaic of different elements from different models in order to achieve his political message . Plato's intention was to paint a picture of Atlantis that the reader would associate with contemporary enemies of Greece. Plato may have consciously taken the Persian Empire as a model for the political structure of Atlantis. The organization of the royal power in Atlantis, with an "upper king" and nine " lower kings", is strongly reminiscent of the Persian hierarchy of the great king and satraps subordinate to him . Likewise, the Persian summer residence Ekbatana, as described by Herodotus, seems to be a model for the description of the capital of Atlantis; while Plato speaks of three concentric rings of water around the Acropolis, Herodotus describes the city fortifications of Ekbatana with "a total of seven wall rings", namely "one wall ring in the other" (1, 98, 3-6). Carthage could have been used as a model for the port facility . The plot core of the Atlantis story, namely the failed attack of Atlantis on Athens, is likely to be the Persian Wars and in particular the constellation of the Battle of Marathon 490 BC. Have served as a model. In both cases the relatively small Athens, completely on its own, struck an attacking superior force and thus saved the whole of Greece from submission. The failed conquest of the sea power Atlantis could also be understood as a reflection of the Sicily expedition, in which the high-spirited plans of the sea power Athens to subjugate all of Sicily and then Carthage, failed grandly. Plato's multiple visits to Syracuse and his attempt to put his political ideas into practice there could also have inspired the Atlantis story.

The city of Helike could have served as inspiration for the characteristic and still most fascinating part of the Atlantis legend - the fall of the island kingdom as a result of a natural disaster . This once very rich city on the north coast of the Peloponnese sank in the winter of 373 BC. In a tidal wave that was triggered by a severe earthquake in the Gulf of Corinth . This catastrophe, in which almost all of the residents of Helike lost their lives, had a strong echo in antiquity (e.g. Diodorus 15, 48, 1–3). As on Atlantis, a Poseidon cult was practiced in Helike; In front of the great temple of Poseidon Helikonios there was once a monumental consecrated statue of the sea god, which is said to have been visible from the surface of the water even after the city fell. Like Atlantis, Helike seemed to have perished through the “power” of the god she actually worshiped. Even before the helicopter flood, another serious flood disaster occurred during Plato's lifetime. This followed in 426 BC. An earthquake in the Gulf of Evia and destroyed the city of Orobiai and an island called Atalante ( Thucydides 3, 89). Due to the similarity of the name, this island Atalante was considered by some researchers as a model for the doom of Atlantis. However, due to the more devastating consequences and the temporal proximity to the writing of "Timaeus" and "Kritias", Helike is seen as a role model.

The French historian Pierre Vidal-Naquet sees Atlantis as an analogy to primeval Athens and thus to the cosmology of the Timaeus dialogue, primordial Athens in this sense corresponds to “being”, whereas Atlantis corresponds to “becoming”. Vidal-Naquet comments: “So we are faced with a sequence that clearly looks like a reflection: 5 (3 + 2), 1, 2, 2, 3, 3. If you leave the island in the middle, you step very quickly into the world of doubling. ”The meaning of double and threefold distances in the“ structure of the world soul ”can already be found in“ Timaeus ”(Tim. 36d). At the same time, Atlantis reflects the decadent Athens of its time. Similarities to Herodotus Persia and Homer's Scheria only play a marginal role, according to Vidal-Naquet; he excludes an analogy to the Persian Wars. Vidal-Naquet believes he recognizes the city complexes of Ekbatana, Babylon, Scheria, Athens and Susa in Atlantis.

The German classical philologist Nesselrath, on the other hand, sees parallels in Atlantis with the city and port facilities of Ekbatana, Babylon and Carthage. He also thinks he can identify analogies with Herodotus' description of the Persian Wars and Homer's epics.

It is controversial in research whether and to what extent there could have been a substantial inspiration of the Atlantis myth from Egyptian sources. Some, such as William Heidel, interpreted the report's alleged origin in Egypt as an open reference to the fictional nature of the Atlantis story. For this they could refer to the words in “ Phaedrus ”: “O Socrates, you can easily compose stories from Egypt or any other country, from wherever you want” (Phaedrus 275 B). Other historians, such as Thomas Henri Martin and Alexander von Humboldt , considered an Egyptian tradition as the core of the myth to be probable and, furthermore, the tradition from Solon, who traveled to Egypt to the narrator of Critias, as possible. To consider an Egyptian origin for parts or aspects of the Atlantis myth as possible does not force one to believe that the Atlantis account - as claimed by Plato - goes back to a 9,000 year old tradition in Egypt. It also seems unlikely that Solon († around 560 BC) was the source for Plato's account, since in the more than 150 years between Solon and Plato no trace of such a report can be found in any Greek writer . The Athenians were also unaware of their alleged victory over Atlantis. If this had really been one of the “greatest heroic deeds of Athens”, it should at least be mentioned in one of the numerous funeral speeches in which the great history of Athens was summed up in honor of the deceased. But there is no mention of Atlantis in any of the speeches handed down to this day. Atlantis is not even mentioned in the funeral oration written by Plato in Menexenos ; which could mean that even Plato did not know the Atlantis story before writing his late works Timaeus and Critias , but only got to know or invented them at that time.

Criticism of the interpretation of Atlantis as an invention of Plato

There are various ways of criticizing the interpretation of the Atlantis story as an invention of Plato. Partly the philological argument is directly attacked, partly an Egyptian tradition is assumed, partly concrete localizations of Atlantis are suggested.

Criticism of the philological argument

The philological justification of the invention hypothesis has repeatedly been criticized. In the words of John V. Luce :

"The skeptics have strong arguments, but nevertheless there was always a minority of scholars who were willing to admit the possibility that Plato used material in his Atlantis story that was not entirely without historical weight."

As indications for a possible historical weight of the Atlantis story are given:

- Plato always clearly identified the parables he invented as myths. The story of Atlantis, on the other hand, was expressly identified as “logos alēthēs” (a true report) and not as “mythos” (a story). Plato emphasized that his tradition was not invented, but was true "in every respect".

- It is hardly to be assumed that Plato would have included a story in his overall plan of the dialogue trilogy Timaeus / Critias / Hermocrates which he himself invented from beginning to end and which he knew was fictional.

- The function of the Atlantis story as evidence of the correctness of Plato's theories of the state can only be fulfilled if it is a true story.

- The detailed and precise description of Atlantis with the naming of numerous details was unnecessary if Atlantis was only to serve as an illustrative model for an ideal state. Plato also showed no interest in technical details in his other works.

- Details of the Atlantis story also appeared in other dialogues of Plato in a clearly historical context.

Theories of a pre-Platonic Atlantis tradition

Since there are striking similarities between the description of an Atlantean royal ritual - to hunt bulls "without weapons, but with sticks and snares" (Critias 119d – e) - and the representation of Minoan bullfights, John V. Luce considers it probable that an Egyptian tradition via the Minoans found entry into Plato's picture of Atlantis. He assumes that Plato himself took note of this tradition in Egypt. Apart from the fact that Plato's trip to Egypt is in itself controversial, he could not read any Egyptian hieroglyphics. He would have had to rely on an Egyptian translator. If he was actually in Egypt, it would still be unclear whether and how the presumed tradition was translated for him and what Plato in turn took over from it for his story.

The philologist Herwig Görgemanns provides a comparable theory of a pre-Platonic Atlantis . He claims that the fraternization of the Egyptians with the "original Athenians" mentioned by Plato was influenced by an Egyptian report. This report is based on the tradition of the sea peoples invasion of 13/12. Century BC And was supplemented by an alleged fraternization of the Egyptians and Athenians against the "enemies from the west" that already existed at that time. When Egypt in the 4th century BC Began to break away from Persian rule, it got first from 386 to 380 BC. Support from Athens by the Athenian general Chabrias . This was not only approved in Athens, and so it was in 362/61 BC. BC (immediately before the creation of Timaeus ) sent an embassy to Athens, which was supposed to promote an Athenian-Egyptian alliance and, according to Görgemanns, spread the changed tradition of the sea peoples storm in Athens. And it is precisely this element that Plato processed in the Atlantis myth. However, this argument is also sketchy in that Plato would probably not have been the only one who would have heard this story. In this respect it would be difficult to explain why only he reports on Atlantis.

Localization hypotheses

In addition to these rather complementary theories on Plato's invention of Atlantis, there are numerous localization hypotheses that suspect Atlantis at a specific location and assume its demise as a specific event. They are based on the common view that Plato's story is based on an actual tradition or at least contains a historical core. At the same time, most theories presuppose that Plato's information on the place and time of Atlantis was incorrect or that the alleged tradition was distorted.

So far, however, these attempts at localization have always remained hypotheses of individual people. The early theories - which Atlantis suspected on Heligoland, the Canary Islands or Crete - are no longer supported by any scientist today. The more recent theories include the hypothesis of the geoarchaeologist Eberhard Zangger that Atlantis is a distorted representation of Troy , as well as the assumption by Siegfried Schoppe and Christian Schoppe that there is a connection between Atlantis and the flooding of the Black Sea basin around 5600 BC. Would exist; According to this hypothesis, the Atlantis story goes back to the decline of a hypothetical culture in the northwest of the Black Sea.

Ancient historians and philologists generally reject any attempt at localization as a misinterpretation of a single source, namely Plato, and see Atlantis as pure fiction that is not based on a historical event or a scientific process.

Impact history

Hardly any ancient report had such an intense aftereffect as Plato's descriptions of “Atlantis”. For many centuries the fabulous island kingdom has served utopians as inspiration and is sought after by archaeologists. The entertainment industry also discovered the subject as a powerful subject.

Antiquity

There is no known publication of Plato's contemporaries that considered the Atlantis story to be “true history”, even after the publication of Timaeus and Critias , the defense of the Atlantic attack was not mentioned in any list of heroic deeds of the Athenians known today. Whether Aristotle , Plato's most famous student, commented on Atlantis is still uncertain. Some see the opinion of Poseidonios handed down by Strabo (2, 3, 6) on the “legend of the island of Atlantis”, which is based on Aristotle, as evidence of this. According to another view, Strabon's execution only proves by reproducing Poseidonios' statement that Atlantis may not be an invention, in contrast to Homer's "Wall of the Achaeans " (see below). Poseidonios did not commit himself to Atlantis.

The philosopher Krantor von Soloi , who wrote the first commentary on Plato's Timaeus , was the first we know to consider Atlantis to be a historical fact. He is said to have been the first to prove the Egyptian tradition of the Atlantis tradition. In his work, which is only available in fragments from Proclus , he reports that he found the stelae with the Egyptian version of the Atlantis report in Sais ( FGrHist 665, F 31). To date, this has been assessed by some researchers as evidence of the Egyptian tradition of Atlantis history. Krantor's report, however, is unbelievable in the majority opinion insofar as he speaks of inscriptions on steles ( στῆλαι ), while the Timaeus speaks of written representations that can be "taken to hand" ( τὰ γράμματα λαβόντες - Tim. 24a), i.e. for example papyrus rolls .

The question of whether Atlantis is a real story is also discussed by later authors, such as Poseidonios, whose opinion is stated by Strabo in the following words:

“But that the earth sometimes rises and falls, and suffers changes as a result of earthquakes and other similar events, which we have also listed, that is from him [sc. Poseidonios] has been correctly noted, and with this he also appropriately puts together Plato's view that it can be assumed that the legend of the island of Atlantis is not a fiction either, of which, as the latter reports, Solon, instructed by the Egyptian priests, told that it once existed, but [later] disappeared, not inferior in size to a mainland; and to say this seems more advisable to him than that its inventor destroyed it again, like the poet [Homer: Iliad 7, 337. and 436.] the wall of the Achaeans. "

While Pliny still expresses doubts about the authenticity of the story as a whole (nat. 2, 92, 205), Plutarch at least considers the Egyptian tradition to be possible, but otherwise does not want to determine whether it is a question of myth or truth (Plut. Solon 31 ). The Platonist Numenios , who lived in the middle of the 2nd century, accepted the battle of the city of Athens against Atlantis as a mere poetry without a historical background, as a poetic fiction. The late antique Neo-Platonist Proclus , on the one hand, believed Atlantis to be real, on the other hand, he also sought a symbolic interpretation. Other authors, such as the church father Tertullian , use Atlantis without reservation as a historical paradigm . However, after the Byzantine Kosmas Indicopleustes recorded the fictional character of the Atlantis report in the 6th century , it was finally forgotten in the European Middle Ages .

As a template for utopias, Atlantis was probably already used in antiquity. For example with Euhemeros von Messene, whose fictional island Panchaia shows similarities to Atlantis as well as to “Ur-Athens” (Diodorus 5, 41-46). Panchaia is portrayed as an exceptionally fertile island on which society - like on Atlantis - is divided into three classes. In the middle of the island there is a large temple dedicated to Zeus . Another ancient author, Theopompus of Chios, satirized Plato's Atlantis story in his work Philippika. It tells of a country called Meropis on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, from which an army with ten million soldiers marched out of the “City of Warriors” (“Machimos”) to subdue the Hyperboreans on the other side of the ocean ( FGrHist 115, F 75). Theopompus' place of Solon and the priest of Sais was the mythical King Midas and a hybrid of man and horse .

Modern times

In the early modern period, the ancient Roman and Greek manuscripts were rediscovered by the scholars, and so the story of Atlantis spread again. With the discovery of America in 1492 , the Atlantis legend gained a certain plausibility, as it was assumed that America was at least the remnant of the sunken continent. Bartolomé de Las Casas wrote in his work Historia general de las Indias : “ Columbus could reasonably believe and hope that, although that great island was lost and sunken, others would have stayed behind, or at least the mainland and that if one were looking for it, one would find them. " also, Girolamo Fracastoro , known for his description of syphilis , America and Atlantis continued the same.

A number of early modern philosophers adopted the Platonic method of social criticism through a sham story. The first to do this was the Englishman Thomas More in 1516 with his work Utopia. While More is only based on Plato's Politeia , the utopians of the following period referred explicitly to the Platonic myth of Atlantis. About a century after More's utopia, the Italian Dominican Tommaso Campanella used Atlantis and the description of Iambulos as a model to create his own state utopia . This is called La città del Sole in the Italian version and also uses the form of dialogue, in this case between a well-traveled Genoese admiral and a hospitaller . Campanella's fictional sunny state is located on the real island of Taprobane (today Sri Lanka ). In particular when describing the city, Campanella is based on Plato's description of Atlantis in “Kritias”: “A huge hill rises on a wide plain, over which the greater part of the city is built. But their multiple rings extend a considerable distance from the foot of the mountain. [...] It is divided into seven huge circles or rings, which are named after the seven planets. "

Almost at the same time as Campanella, around 1624, Francis Bacon wrote his utopia Nova Atlantis in England , the title of which referred to Plato. He used Plato's Atlantis as a historical fact and identified it with America in order to give his own utopia an apparent credibility. A flood once destroyed the "old Atlantis" with the exception of a few survivors. Bacon's “new Atlantis” is a South Sea island called Bensalem , on which - very similar to Plato - a hierarchical, monarchist state order, patriarchal family structure and Christian moral rigor can be found. The center of power is the "House of Salomon", in which a god-chosen, "venerable father" is enthroned. Bacon's work remained unfinished and was published by William Rawley only after his death . According to Rawley, Bacon's early death is the reason there is no social criticism in it.

In the course of the 16th and 17th centuries, Atlantis was increasingly declared by scholars to be the origin of human civilization and thus also interesting for "weaving" into one's own national myths.

While the remains of the sunken island were first seen in America - which justified the claim of the Spanish Conquista - the polymath and rector of Uppsala University Olof Rudbeck declared in his four-volume work Atlantica sive Manheim, vera Japheti posterorum sedes at the end of the 17th century ac patria (1679 to 1702, Swedish Atland eller Manheim ), Sweden to Atlantis and Uppsala to its capital. In his writings, Rudbeck mixed Plato's Atlantis with set pieces from the Edda as well as legends about Noach's alleged grandson Atlas, who settled in the north. With this eclecticism he attempted to challenge the people of Israel to be chosen and to make Sweden the birthplace and ancestral land of all the peoples of Asia and Europe; in addition, he postulated that the runes were the forerunners of the Phoenician and Greek letters. He called Plato a liar who had managed to prevent the discovery of the true northern Atlantis. Rudbeck was one of the first to take Atlantis and its presumed localization for political and ideological purposes.

In the 19th century, interest in Atlantis was re-awakened by the bestseller by the American progressivist politician Ignatius Donnelly , published in 1882 . In his book Atlantis - The antediluvian World (Eng .: "Atlantis - die vorsintflutliche Welt", 1911) he claimed in 1882 that the Atlantis described by Plato was located in the Atlantic and was the common origin of the early advanced civilizations both in the Mediterranean area (especially in the old Egypt ) as well as in Central America . He relies on the research of Charles Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg and Augustus Le Plongeon , among others . He also believed that Atlantis was the original home of the Aryans . Donnelly described Atlantis as an agrarian land of peace and happiness that is remembered in various civilizations, whether as the Garden of Eden , the Garden of the Hesperides, or Asgard . In the subsequent volume Ragnarok - The Age of Fire and Gravel from 1883, he then described the destruction of this paradise after it had been morally corrupted. He understood this historical narrative as a warning to the USA of his presence.

The story of Atlantis was also vividly received in esoteric and occultism . In theosophy , anthroposophy and ariosophy the "Atlanteans" were seen as representatives of one of seven human epochs, and in the Hermetic Philosophy Cosmique they are the origin of occult teachings. Donnelly's bestseller helped give credibility to such theses. Despite all the difference, the historian Franz Wegener draws a connecting line between these currents, representatives of the Conservative Revolution , supporters of the World Ice Doctrine, National Socialists and the New Right, and puts forward the hypothesis of an “Atlantid target image”, “a target image that its carriers unconsciously accelerate in motion rushing towards self-destruction ”.

In particular in the German-speaking area during the Weimar Republic and during the Third Reich, models of the reception of Atlantis were cultivated in ethnic and National Socialist circles, the proponents of which were Plato's sunken island realm, especially in the North Sea and at the North Pole - the alleged Nordic continent Arktogäa. localized or equated with the legendary Thule and declared it the original home of the “Aryan master race”. One of the pioneers of this racist-ideological reception of the Atlantis report was above all Guido von List , one of the protagonists of the so-called ariosophy ; at the time known authors of corresponding Atlantis literature were z. B. Karl Georg Zschaetzsch , Herman Wirth , and Heinrich Pudor . Via Alfred Rosenberg and Heinrich Himmler , the Atlantis idea became part of the unofficial NSDAP party ideology.

After the collapse of National Socialism, such ideas were initially mainly propagated outside of Germany. B. by Julius Evola and the right-wing Chilean author Miguel Serrano . In this country after 1945, however, “Nordic” Atlantis concepts, which are not part of the “ario-Atlantean” line of tradition, were enthusiastically taken up and ideologically instrumentalized in circles of the “old” and “ new right ”, especially Jürgen Spanuth's positioning of Atlantis Heligoland and his thesis that the Atlanteans are part of the Nordic culture of the Bronze Age.

Sometimes Atlantis is used as a synonym for a rich and powerful culture that suddenly and unexpectedly perished. For example, Thomas Edward Lawrence spoke of the once magnificent, but later silted up South Arabian metropolis of Ubar as the “Atlantis of the Sands”. The legendary, sunken Baltic port of Vineta is sometimes referred to as the “Atlantis of the North”. Little more has remained in fiction than this symbolization of Atlantis, which has been increasingly taken up by writers since around 1850. In Jules Verne's 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, for example, Captain Nemo and Professor Aronnax visit the ruins of Atlantis on the ocean floor. As a symbol for a fantastic alternative world, Atlantis appears as early as 1814 in the romantic novella Der goldenne Topf by E. T. A. Hoffmann .

See also

- Atlantis as a subject (in art and culture)

- Localization hypotheses for Atlantis

Antique reception

- Claudius Aelianus , De natura animalium 15, 2 ( → German translation by Friedrich Jacobs 1841)

- Kosmas Indicopleustes , Topographia Christiana 12 ( archive.org English translation by John Watson McCrindle 1897)

- Plinius , Naturalis historia 2, 92 (90) ( archive.org German translation by Philipp Hedwig Külb 1840, → English translation by John Bostock and Henry Thomas Riley 1893)

- Plutarch , Solon 26, 1 - Internet Archive (with English translation by Bernadotte Perrin 1914)

- Plutarch, Solon 31, 3 - Internet Archive (with English translation by Bernadotte Perrin 1914)

- Plutarch, Solon 32, 1 - Internet Archive (with English translation by Bernadotte Perrin 1914)

- Proklos , in Timaeum 1, 24 A – E ( archive.org English translation by Thomas Taylor 1820)

- Proklos, in Timaeum 1, 53 B – C ( archive.org English translation by Thomas Taylor 1820)

- Proklos, in Timaeum 1, 53 E – F ( archive.org English translation by Thomas Taylor 1820)

- Proklos, in Timaeum 1, 54 F ( archive.org English translation by Thomas Taylor 1820)

- Strabon , Geographica 2, 3, 6 ( archive.org German translation by Albert Forbiger 1856)

literature

- Ernst Hugo Berger : Atlantis . In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume II, 2, Stuttgart 1896, Col. 2116-2118.

- Reinhold Bichler : Athens defeats Atlantis. A study of the origin of the state utopia. In: Canopus . 20, 1986, No. 51, pp. 71-88.

- Wilhelm Brandenstein : Atlantis. Vienna 1951

- Burchard Brentjes : Atlantis. Story of a utopia. DuMont, Cologne 1993, ISBN 3-7701-2910-5 .

- Richard Ellis: Imagining Atlantis. Knopf, New York 1998, ISBN 0-679-44602-8 .

- Paul Friedländer: Plato I. Truth of being and reality of life. de Gruyter, Berlin 1954. (1975, ISBN 3-11-004049-2 ).

- Angelos George Galanopoulos, Edward Bacon: The Truth About Atlantis . Wilhelm Heine Verlag, Munich 1976, ISBN 3-453-00654-2 (English: Truth Behind the Legend . Translated by Helga Künzel).

- Jean Gattefossé, Claudius Roux: Bibliographie de l'Atlantide et des questions connexes. Impr. Bosc frères & Riou, Lyon 1926

- Friedrich Gisinger : On the geographical basis of Plato's Atlantis. In: Klio . 26, 1933, ISSN 0075-6334 , pp. 32-38.

- Joscelyn Godwin: Arktos: The Polar Myth in Science, Symbolism, and Nazi Survival. , Kempton ILL 1996

- Herwig Görgemanns : Truth and Fiction in Plato's Atlantis Story. In: Hermes . Volume 128, 2000, ISSN 0018-0777 , pp. 405-420.

- Williams KC Guthrie: The later Plato and the Academy. A History of Greek Philosophy. Volume 5, Cambridge 1980

- Paul Jordan: The Atlantis Syndrome. Sutton Publishing, Stroud Glou 1994, ISBN 0-7509-3518-9 .

- Zdenek Kukal: Atlantis in the Light of Modern Research. Academia, Prague 1984

- Kathryn A. Morgan: Designer history. Plato's Atlantis story and fourth-century ideology. In: Journal of Hellenic Studies . Volume 118, 1998, ISSN 0075-4269 , pp. 101-118.

- Gianfranco Mosconi: I peccaminosi frutti di Atlantide - iperalimentazione e corruzione. In: Rivista di Cultura Classica e Medioevale. Volume 51, No. 2, 2009, pp. 331-360.

- Gianfranco Mosconi: I numeri dell'Atlantide: Platone fra esigenze narrative e memorie storiche. In: Rivista di Cultura Classica e Medioevale. Volume 55, No. 1, 2010, pp. 331-360.

- Otto Muck : Everything about Atlantis: old theses, new research. Co-author Theodor Müller-Alfeld, editor F. Wackers. Econ, Munich 1976, ISBN 3-430-16837-6 .

- Heinz-Günther Nesselrath : Plato and the invention of Atlantis. KG Saur, Munich / Leipzig 2002, ISBN 3-598-77560-1 .

- Gunnar Rudberg : Atlantis och Syrakusai. 1917. ( Atlantis and Syracuse. 2012, ISBN 978-3-8482-2822-5 ).

- Edwin S. Ramage (Ed.): Atlantis. Myth, riddle, reality? Umschau, Frankfurt am Main 1979, ISBN 3-524-69010-6 .

- Lyon Sprague de Camp: Sunken Continents. From Atlantis, Lemuria and other perished civilizations. Heyne, Munich 1975, ISBN 3-453-00504-X .

- Thomas A. Szlezák : Atlantis and Troy, Plato and Homer. Comments on the claim to truth of the Atlantis myth. In: Studia Troica . Volume 3, 1993, ISSN 0942-7635 , pp. 233-237.

- Pierre Vidal-Naquet : Athens and Atlantis. Structure and meaning of a platonic myth. In: Pierre Vidal-Naquet: The Black Hunter. Frankfurt am Main 1989, ISBN 3-593-33965-X , pp. 216-232.

- Pierre Vidal-Naquet: Atlantis. Story of a dream. Translated from the French by A. Lallemand. CH Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-406-54372-3 . ( Books.google.de ) Partial view

- Franz Wegener: The Atlantid worldview. National Socialism and the New Right in search of the sunken Atlantis. Kulturförderverein Ruhrgebiet KFVR, Gladbeck 2003, 3rd ext. 2014 edition

- Source collection

- Oliver Kohns, Ourania Sideri: Myth of Atlantis. Texts from Plato to JRR Tolkien. Reclam-Verlag, Stuttgart 2009, ISBN 978-3-15-020178-7 .

Web links

- Plato: Timaeus. www.zeno.org, accessed on January 20, 2011 (translation: Franz Susemihl , 1856).

- Plato: Critias. www.zeno.org, accessed on January 20, 2011 (translation: Franz Susemihl, 1857).

- Atlantis-Scout Extensive information portal on Plato's Atlantis including a download center with contributions and a translation of the dialogues Timaeus and Critias

- Scientific literature on Atlantis compiled by Rainer W. Kühne.

- James W. Mavor Jr .: The Minoan Atlantis of Dr. Angelos Galanopulos. wiki.atlantisforschung.de, accessed on January 7, 2011 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Kathryn A. Morgan: Designer History - Plato's Atlantis Story and Fourth-Century Ideology . In: Journal of Hellenic Studies (JHS) . No. 118 . Hellenic Society, November 1998, ISSN 0075-4269 , pp. 101–118 , here: p. 107 ( de.scribd.com [accessed December 10, 2014]).

- ^ Plutarch : Parallel life descriptions: Solon. XXXII. 1–2 ( original and English translation - Internet Archive by Bernadotte Perrin).

- ↑ Such a high age specification was not uncommon in antiquity. B. Herodotus an age of 11340 years for Egypt ( Historien. II 142.3; original and English translation by George Campbell Macaulay).

- ^ A b Pierre Vidal-Naquet: Athens and Atlantis. Structure and meaning of a platonic myth. In: Pierre Vidal-Naquet: The black hunter. Forms of thought and societies in ancient Greece. Lang, Frankfurt 1989, ISBN 3-593-33965-X , pp. 216-232.

- ^ William Keith Chambers Guthrie : The later Plato and the Academy . In: A History of Greek Philosophy . tape 5 . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1978, ISBN 0-521-29420-7 ( archive.org ).

- ^ Pierre Vidal-Naquet: Athens and Atlantis. Structure and meaning of a platonic myth. In: Pierre Vidal-Naquet: The black hunter. Forms of thought and societies in ancient Greece. Lang, Frankfurt 1989, ISBN 3-593-33965-X , p. 231 f.

- ↑ Heinz-Günther Nesselrath : Plato and the invention of Atlantis (= Lectio Teubneriana XI ). KG Saur, Munich / Leipzig 2002, ISBN 3-598-77560-1 , p. 38 .

- ↑ Heinz-Günther Nesselrath: Plato and the invention of Atlantis (= Lectio Teubneriana. XI). KG Saur, Munich / Leipzig 2002, p. 32 f.

- ↑ Thomas A. Szlezák : Atlantis and Troia, Plato and Homer. Comments on the claim to truth of the Atlantis myth . In: Studia Troica . No. 3/1993 . Philipp von Zabern, 1993, ISSN 0942-7635 , p. 233-237, here: p. 235 f .

- ^ Gunnar Rudberg : Atlantis and Syracuse - Did Plato's experiences on Sicily inspire the legend? Ed .: Thorwald C. Franke. Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2012, ISBN 978-3-8482-2822-5 (Swedish: Atlantis och Syrakusai - En studie till Platons senare skrifter . Uppsala 1917. Translated by Cecelia Murphy).

- ↑ Lyon Sprague de Camp : Sunken Continents - From Atlantis, Lemuria and other perished civilizations (= Heyne books . No. 7010 ). Heyne, Munich 1975, ISBN 3-453-00504-X , p. 241 (English: Lost Continents - The Atlantis Theme in History, Science, and Literature . New York 1954. Translated by Brigitte Straub).

- ↑ Heinz-Günther Nesselrath: Plato and the invention of Atlantis (= Lectio Teubneriana. XI). KG Saur, Munich / Leipzig 2002, p. 26 f.

- ^ Pierre Vidal-Naquet: Athens and Atlantis. Structure and meaning of a platonic myth. In: Pierre Vidal-Naquet: The black hunter. Forms of thought and societies in ancient Greece. Lang, Frankfurt 1989, ISBN 3-593-33965-X , p. 228.

- ↑ Heinz-Günther Nesselrath: Plato and the invention of Atlantis (= Lectio Teubneriana. XI). KG Saur, Munich / Leipzig 2002, p. 25.

- ^ William A. Heidel: A suggestion concerning Platon's Atlantis. In: Daedalus . Volume 68, 1933, ISSN 0011-5266 , pp. 189-228.

- ↑ Thomas H. Martin: Dissertation on l'Atlantide. In: Thomas H. Martin: Études sur le Timée de Platon. Volume 1, Paris 1841, pp. 257-332.

- ↑ John V. Luce : The literary perspective - the sources and the literary form of Plato's Atlantis story . In: Edwin S. Ramage (Ed.): Atlantis - Myth, Riddle, Reality? Umschau, Frankfurt am Main 1979, ISBN 978-3-524-69010-0 , pp. 65 ff (English: Atlantis - Fact Or Fiction? Bloomington, Indiana 1978. Translated by Hansheinz Werner).

- ↑ Wilhelm Brandenstein : Atlantis - Size and Fall of a Mysterious Island Empire (= work from the Institute for General and Comparative Linguistics at the University of Graz . No. 3 ). Gerold & Co., Vienna 1951.

- ↑ John V. Luce: The literary perspective - the sources and the literary form of Plato's Atlantis story. In: Edwin S. Ramage (Ed.): Atlantis - Myth, Riddle, Reality? Umschau, Frankfurt am Main 1979 (original title: Atlantis - Fact Or Fiction? Bloomington, Indiana 1978, translated by Hansheinz Werner), ISBN 978-3-524-69010-0 , p. 89 f.

- ↑ Herwig Görgemanns : Truth and Fiction in Plato's Atlantis Story . In: Hermes . Journal of Classical Philology. No. 128 . Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 2000, p. 405-419 ( partial view [accessed December 11, 2014]).

- ↑ Reinhold Bichler : Atlantis. In: The New Pauly. History of reception and science. Vol. 13, JB Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 1999, Col. 335 f.

- ^ Strabo : Geographica. 2, 3, 6. ( archive.org German translation by Albert Forbiger 1856)

- ↑ Compare for example Ernst Hugo Berger: Atlantis . In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume II, 2, Stuttgart 1896, Col. 2117.

- ^ Andreas Hartmann : Atlantis. Know what's right. Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 2010 ISBN 978-3-451-06115-8 , pp. 61 and 64; Heinz-Günther Nesselrath: Atlantis after Plato - Comments on a new history of reception of the island invented by Plato. In: Annual issue of the Göttingen Friends of Ancient Literature Association. No. 16 (2017), pp. 12-24.

- ^ Heinz-Günther Nesselrath: Atlantis on Egyptian steles? The philosopher Krantor as an epigraphist. In: Journal of Papyrology and Epigraphy . 135, 2001, pp. 33-35, here: p. 34. ( online , PDF file, 49.73 kB).

- ^ Matthias Baltes : Numenios of Apamea and the Platonic Timaios . In: Festgabe for O. Hiltbrunner for his 60th birthday (= Vigil. Christ . Band 29 [1975] ). Münster 1973, p. 241–270 , No. 1, here p. 5 ( books.google.de - partial view).

- ↑ Bartolomé de Las Casas: Historia de las Indias. 1527 ff., Quoted from Burchard Brentjes: Atlantis. Story of a utopia. DuMont, Cologne 1993, ISBN 3-7701-2910-5 , p. 66.

- ↑ Girolamo Fracastoro: Syphilis sive Morbus gallicus. Vol. 3, 1530 ( books.google.de edition of 1536).

- ^ T. Campanella : Civitas Solis, idea republicae philosophicae. 1623 ( zeno.org German translation).

- ^ Klaus J. Heinisch: The utopian state. More Utopia. Campanella sun state. Bacon Nova Atlantis. 26th edition. Rowohlt, Reinbek 2001, ISBN 3-499-45068-2 , p. 188 f.

- ^ Burchard Brentjes : Atlantis - History of a Utopia . DuMont, Cologne 1993, ISBN 978-3-7701-2910-2 , pp. 89 .

- ↑ On the “history of discovery” in modern times, see overall: Pierre Vidal-Naquet: Atlantis. Story of a dream. C. H. Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-406-54372-3 , pp. 57-76.

- ^ Pierre Vidal-Naquet: Athens and Atlantis. Structure and meaning of a platonic myth. In: Pierre Vidal-Naquet: The black hunter. Forms of thought and societies in ancient Greece. Lang, Frankfurt 1989, ISBN 3-593-33965-X , p. 219.

- ↑ Kenneth L. Feder: Encyclopedia of Dubious Archeology. From Atlantis to the Walam Olum. ABC Clio, Santa Barbara, CA 2010, p. 89.

- ↑ Ignatius Donnelly: Atlantis - The antediluvian World. Harper & Brothers, New York 1882. ( sacred-texts.com accessed March 15, 2014); also on the following Richard Ellis: Imagining Atlantis. Knopf, New York 1998, pp. 38-44.

- ^ Isaac Lubelsky: Mythological and Real Race Issues in Theosophy. In: Olav Hammer, Mikael Rothstein (Eds.): Handbook of the Theosophical Current. Brill, Leiden 2013, p. 340.

- ↑ Jean Pfaelzer: The Utopian Novel in America, from 1886 to 1896. The Politics of Form. University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, PA 1984, p. 122.

- ^ Isaac Lubelsky: Mythological and Real Race Issues in Theosophy. In: Olav Hammer, Mikael Rothstein (Eds.): Handbook of the Theosophical Current . Brill, Leiden 2013, p. 340.

- ↑ Franz Wegener: The atlantidische worldview. National Socialism and the New Right in search of the sunken Atlantis. Kulturförderverein Ruhrgebiet KFVR, Gladbeck 2003, 3rd ext. 2014 edition. Series: Political Religion of National Socialism, Dept. 1_ Das Wasser. ISBN 1-4936-6866-8 Summary after Wegener: The Atlantic world view. ( Memento of April 30, 2009 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Karl Georg Zschaetsch: Atlantis, the original home of the Aryans. Arier-Verlag, Berlin 1934.

- ↑ Herman Wirth: The rise of mankind. Investigations into the history of religion, symbolism and writing of the Atlantic-Nordic race . E. Diederichs, Jena 1928.

- ^ Heinrich Pudor: Peoples from God's breath. Atlantis-Helgoland, the Aryan-Germanic racial high breeding and colonization motherland. Leipzig 1936.

- ↑ Miguel Serrano: Adolf Hitler - The Last Avatar. 1984 - Alfabeta Impresores, Santiago / Chile 2004.

- ↑ Jürgen Spanuth: ... and yet: Atlantis unraveled! - A reply from Jürgen Spanuth. Osnabrück (Otto Zeller Verlag) 1957 and 1980.