Bartolome de Las Casas

Bartolomé de Las Casas (* 1484 or 1485 in Seville ; † July 18, 1566 near Madrid ) was a Spanish theologian, Dominican and writer and the first bishop of Chiapas in what is now Mexico. Las Casas first stayed as a colonist in the new Spanish possessions in America from 1502 and from 1514 became one of the sharpest and most respected critics of the Conquista as well as a champion for the situation of the Indians in the conquered areas. He wrote detailed historical treatises on this for the period between 1492 and 1536, of which he was an eyewitness, and pamphlets for the rights of the Indians. He was also known as the "apostle of the Indians".

Life

Childhood and youth

Bartolomé de Las Casas was born in Seville in 1484 or 1485. He grew up in a simple family. His father was a merchant; his mother ran a bakery. Las Casas attended the Cathedral School in Seville and then studied ancient languages, history and philosophy.

Las Casas had an early connection to the conquest of the American continent by the Spaniards, because his father Pedro and his uncle Francisco Peñalosa accompanied Christopher Columbus on his second trip to the island of Hispaniola . From this the father brought the fourteen-year-old an Indian boy with him who had been enslaved on the island. An intense relationship developed between the two boys for a year and a half. Since the Spanish Queen Isabella I declared the enslavement of her newly acquired subjects to be unlawful, those who were brought to Spain were sent back to their homeland. They met again later on Hispaniola.

Year of birth

It was long assumed that Las Casas was born in 1474. Therefore, Spain and Latin America celebrated his 500th birthday in 1974. In 1976 a court record from 1516 was found in which Las Casas gave as a witness on record that he was 31 years old. The subsequent year of birth 1484/85 is now considered certain. Usually 1484 is given as the year of birth.

Colonist and Conqueror (1502–1515)

On February 13, 1502, Las Casas set out for the New World himself to settle in Hispaniola. There he took part as a soldier in two campaigns in which the last free indigenous people of the island, the Taíno , were to be brought under Spanish rule. Afterwards he received an allotment of land and from Indios who had to work for him ( encomienda ). From 1506 to 1507 Las Casas went on a trip to Rome to receive the ordination of priests .

In 1511 he took part in the conquest of Cuba as a conquistador . The conquerors under Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar met resistance from the Taíno who lived there. They captured the province's cacique , Hatuey , and burned him alive. Before the execution, a Franciscan brother tried to convince him to convert to Christianity so that he could go to heaven after death . Las Casas later handed down Hatuey's answer:

“Hatuey thought a little and then asked if Christians would go to heaven. The monk said: yes, if they are good Christians. Without further ado, the Kazike said that he didn't want to go to heaven, but to hell, only so that he would not have to see such cruel people and be with them. "

In the course of the campaign, Las Casas was appointed field chaplain . He worked to ensure that the meetings between Spaniards and Indians were as peaceful as possible. Nevertheless, there was a massacre, which he described in his Historia general de las Indias . Thanks to his authority, he was able to save the lives of 40 people by opposing the Spanish soldiers. After the conquest, he ran an encomienda together with a partner. With the Indios assigned to him, he built up a farm, and he sent others to the gold mines.

Rethinking process

Ever since a group of Dominican missionaries came to the New World in 1510, they preached against the unjust treatment of the natives by the Spanish conquerors. On the fourth Sunday of Advent in 1511, the Dominican Antonio de Montesinos gave the so-called "Advent Sermon" in the church of Santo Domingo . He asked the Spanish colonizers present:

“With what right and what justice do you keep these Indians in such cruel and terrible bondage? With what authority did you bloody war against these peoples who lived quietly and peacefully in their countries, tortured and murdered them in countless numbers? You oppress them and plague them without giving them food and healing them in their diseases that come upon them through the immoderate labor that you impose on them, and they die - or rather, you kill them, day by day Day to win gold. "

For these reasons the Dominicans denied absolution to anyone who possessed Indians. When Las Casas tried to make confession to a Dominican, he was refused too. From 1514 he began to rethink his lifestyle:

“[…] Every day the conviction grew in him [Las Casas about himself] that everything that was done to the Indians in these countries was unjust and tyrannical. Later he used to say: From the first hour when he began to dispel the mists of this ignorance, he had never read a book in Latin or Spanish (and that was countless in forty-four years) from which the law of the Indians was not clear and the condemnation of the injustice that was done to them. "

He returned his Indians to the governor of Cuba and left the island in the summer of 1515.

Standing up for the rights of the Indians, missionary attempts in Venezuela

The Spanish King Ferdinand II had enacted the Burgos Laws in late 1512 , which were intended to limit the oppression of the Native Americans. For example, it was banned to force children under fourteen years of age, and the duration of forced labor was set at nine months a year. Las Casas did not go far enough in these laws and, thanks to his relations with the Archbishop of Seville Diego de Deza, obtained an audience with the king. On December 23, 1515 a brief conversation took place at the court in Plasencia . Ferdinand died on January 23, 1516, so that another agreed conversation did not take place. Las Casas went to Madrid to convince the new government of the then sixteen-year-old Charles I of Spain of the urgency of his concern. Above all, he tried to secure an adequate livelihood for the indigenous people who were obliged to work, to ensure that they had sufficient food and medical care.

On September 17, 1516, Las Casas was appointed "Universal Procurator of all Indians in the West Indies". From now on he officially represented their interests before the king and the Council of India . During this time he wrote his first three memoranda, which he wrote to save the Indians. In the third memorial he judges the consequences of the exploitation by the Spanish settlers:

Las Casas achieved the establishment of a commission of inquiry on Hispaniola , with which he set sail again on November 11, 1516. However, the work of this commission was made impossible on site, so that in May 1517 he traveled back to Spain. He was of Charles I to the royal chaplain appointed.

Since hardly any of the locals had survived in the Greater Antilles , Las Casas turned to new mission objectives. On May 19, 1520, he signed a contract with the king, which gave him the Venezuelan coast as a settlement and mission area. The assigned area included the coast from the Paria peninsula to Santa Maria in present-day Colombia and all areas inland. It would have reached the then unknown south coast, i.e. the Strait of Magellan, and thus occupied about half of the South American continent. On December 14th, Las Casas set sail with its settlers. But he was stopped on Hispaniola; his settlers joined a slave expedition. He then went on to Venezuela and lived there as a guest of missionaries of the Franciscan Order in Cumaná . The fathers cultivated some fields there and tried to convince the natives of their friendly intentions. However, the peaceful mission ended with the arrival of Spanish slave hunters. While Las Casas took the ship to Hispaniola in December 1521 to oppose further raids, the Indians killed the friars on the assumption that they had made common cause with the slave hunters. Las Casas retired to the monastery after this failure. The area assigned to him in Venezuela was pledged by the king in 1526 to the Welser people , who founded their colony Little Venice ( Venezuela ) there.

Monastery years (1522-1535)

In 1522 Las Casas began a novitiate in the Dominican convent of Santo Domingo . In 1526 he went to Puerto Plata on the north coast of Hispaniola with two friars to found a new convent there. It was there that he began to work on his comprehensive Historia general de las Indias .

In 1529 he was called to New Spain by the Bishop of Mexico Juan de Zumárraga and the Bishop of Tlaxcala Julián Garcés . In 1531 he traveled to Tenochtitlán , the capital of the former Aztec Empire , which was destroyed by Hernán Cortés in 1521 and rebuilt as a Spanish colonial city. Las Casas had known Cortés since the conquest of Cuba, in which both had participated twenty years earlier. He quickly came into conflict with the Spanish settlers because he denied absolution to anyone who kept Indians as slaves and did not want to release them. After he had refused the final confession to a large landowner with good relations with the king, he was transferred back to Hispaniola from Puerto Plata to the convent of Santo Domingo. In addition to his work on the Historia , he studied theology and probably also law during the years in the monastery .

Activity in Nicaragua and Guatemala (1535–1540)

In 1535 Las Casas set out with the Bishop of Panama for Peru , which had been conquered by Francisco Pizarro three years earlier . There was no wind on the voyage for two and a half months, and when all supplies were used up, the ship had to be abandoned. Las Casas arrived with other survivors in a small boat on the coast of Nicaragua . On foot he came to Granada , then the largest city in Nicaragua. There he learned that there were only a few surviving Indians in Peru. He therefore decided to take up missionary work in Nicaragua. He preached against the war and the exploitation of the Indians and wrote a letter to the royal court. In it he reports that tens of thousands of Indians were captured, branded and sold as slaves to Panama and Peru. Against this - now legalized - practice, Las Casas used theological and legal arguments to claim the rights of the Indians. Because of his work, he quickly came into conflict with the Spanish settlers.

He therefore accepted Francisco Marroquín's invitation , the first bishop of Guatemala since 1534 , to continue his work with him. Marroquín made Las Casas his confidante and deputy. In 1537, Las Casas signed a treaty with the bishop and governor of Guatemala that allowed him and his companions to proselytize the inhabitants of the “Tezulutlán” or “war country” area in the north of the country. The treaty stipulated that no other Spaniards were allowed to enter the area and no wars against the Indians were allowed if Las Casas succeeded in converting the Indians to Christianity in a peaceful way. He named the country Verapaz ("true peace").

This time he met resistance from his own order. In 1538 he was recalled to a religious chapter in Mexico and was not allowed to return after its end. His superiors cited the free life of missionaries in Guatemala as the reason for this, which violated the rules of monastic life. In 1539 he was able to return to Guatemala to continue his mission. On March 12, 1540, he left the country again to bring his concerns to the emperor again. He wrote the Concise Report on the Devastation of the West Indian Countries , with which he addressed the emperor directly.

Bishop of Chiapas (1544–1546)

In 1543, Emperor Charles V decided to propose Las Casas as Bishop of Chiapas. Las Casas achieved that the provinces of Tezulutlán, Lacandó and Socunusco were annexed to the diocese , which in addition to the current Mexican state of Chiapas also included the entire Yucatán peninsula and northern Guatemala. Thus his mission country Verapaz was in his diocese .

On December 19, 1543, Las Casas was appointed Bishop of Chiapas . He was ordained episcopal by the bishop of Modruš , Diego de Loaysa CRSA , on March 30, 1544. Co- consecrators were Cristóbal de Pedraza, bishop of Comayagua , and the auxiliary bishop of Cassano all'Jonio , Pedro Torres. After a long crossing, Las Casas only reached its new official residence in the Ciudad Real de los Llanos de Chiapas a year later . Today this city is called San Cristóbal de las Casas after him . The title of bishop gave him a certain authority over the settlers in the New World, and from now on he was no longer bound by the instructions of the superiors of the order.

First of all, Las Casas went on a trip to Verapaz in May 1545 and was able to report initial successes from there. However, his job as a bishop was made impossible for him by being denied his salary. He was accused of being the author of the New Laws , which had also been passed on his instigation in 1542, and thus of being responsible for the uprising and civil war in Peru. He was slandered by the emperor and threatened with death. At the end of 1545 he asked the emperor to relieve him of his office. The New Laws (Leyes Nuevas) forbade the enslavement of the Indians. However, they were never enforced in the New World and were fought fiercely by the Spanish settlers, so that the emperor had to partially take them back in 1545.

Work in Spain (from 1546)

In December 1546, Las Casas finally returned to Spain at the age of 62. He lived there at the court of Prince Philip and resumed his work as procurator for the Indians. His continued commitment finally paid off when the emperor suspended all conquistas on April 16, 1550 , which was held out for six years. Las Casas wrote a few other works, was an alderman of the Council of India and led the disputation of Valladolid on the future treatment of the Indians with Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda in 1550/51 .

In January 1551 the Pope confirmed to him that he would renounce the office of bishop in Chiapas. Las Casas lived from then on in the monastery of San Gregorio in Valladolid . In the same year he took part in the general chapter of his order in Salamanca as the king's representative . In 1552 he was in his native Seville, where he tried to recruit missionaries for the New World. There he had access to the library of Fernando Columbus , the Biblioteca Colombina , and resumed work on his Historia de las Indias .

In 1553 he returned to the College of San Gregorio. During this time he was occupied with another project to support the survival of the Indians. So far, the Spanish settlers had only received their encomienda , that is, the allocation of land and indigenous people, for a certain period of time. The Spanish "encomenderos" offered the troubled krona eight million pesos to convert the temporary encomienda into one "for ever". Las Casas, for his part, found enough supporters to be able to offer the king a much higher sum in 1559 if he decided against it. However, Philip II was undecided and ultimately made no decision on the matter.

Last years

In November 1559, Las Casas was summoned by the Inquisition as a witness in the trial against Bartolomé de Carranza . His statements contributed to Carranza being acquitted. He was also able to get the king to remove the inquisitor from his office.

On July 18th, 1566, Las Casas died in the Dominican monastery of Our Lady of Atocha near Madrid . It is no longer known where his grave is located.

meaning

Defender of the rights of the Indians

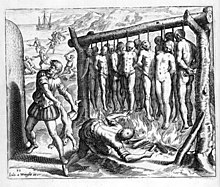

Las Casas gained importance as one of the earliest defenders of the rights of the Indians. His works include some of the earliest indictments of Native American genocide by the Conquistadors . He appeared both as an eyewitness and as a defender of the Indians at court and in the Catholic Church.

Las Casas thus continued the work that had already been started by the first missionaries of the Franciscan and Dominican orders on Hispaniola. Like them, he preached against war and the enslavement of the Indians, lived among them and spoke their languages. At first he was primarily concerned with a peaceful conversion of the Indians to Christianity. He opposed forcible submission and forced conversion, and tried to spread his faith through words and deeds. Later he also questioned the legality of the conquest and thus the Spanish claim to rule over the New World.

In his respective offices as Procurator of the Indians, Alderman of the Council of India or Bishop of Chiapas, he worked to end the war against the Indians and their enslavement. Thanks to his spiritual authority and that of the king's confidante, he was able to achieve some success. For example, the New Laws issued by the king or the Sublimis Deus bull issued by the Pope were also thanks to his influence.

Chronicler of the Conquista

Las Casas wrote one of the earliest and most accurate descriptions of the conquest, from the conquest of Hispaniola by Christopher Columbus (from 1492) to the conquest of Peru (1532-1536). His works contain accounts of the settlement of Hispaniola, the conquest of Cuba and Central America, which he witnessed as an eyewitness, as well as transcripts and summaries of other important contemporary historical documents. Through him an almost verbatim copy of the logbook of Christopher Columbus has been handed down, the detailed report on his first trip to the New World.

Ethnographer of the Indian cultures

Equally important are his testimonies about the life and languages of the Indian peoples. Besides the reports of the missionary Ramón Pané , his records are the only credible accounts of the Taíno . The Taíno lived in the Greater Antilles until the arrival of the Spaniards and, with the exception of a few survivors, had already been destroyed by forced labor, hunger and disease during Las Casas' lifetime.

Las Casas and the transatlantic slave trade

Las Casas has been accused of having introduced, or at least encouraged , the trade in African slaves . The occasion was a report in which he describes how some settlers on Hispaniola made him an offer to release their indigenous slaves if they were given licenses to acquire African slaves in return. Las Casas had agreed to this. For a long time he considered the use of African slaves to be lawful and, as Bishop of Chiapas, had some in his retinue. Later there was a change of heart.

“He [Las Casas on himself] was unaware of the injustice by which the Portuguese captured them and made them slaves. After realizing this he would not have given the advice on anything in the world, for it was always wrong to catch them and tyranny to make them slaves; the negroes have the same rights as the natives. "

From Las Casas the probably oldest text has come down to us, in which the trade in African slaves is described as a sin and a crime.

Works and reception

Bartolomé de Las Casas' main work is the three-volume history of the West Indian countries (Historia general de las Indias) , also known as Historia for short . Among numerous other reports, the Concise Report of the Devastation of the West Indian Countries (Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias occidentales) of 1552 gained importance.

expenditure

- Bartolomé de Las Casas: Obras completas. 15 volumes, Madrid 1989–1995.

- Bartolomé de Las Casas: selection of works. 4 volumes, edited by Mariano Delgado, Paderborn 1994–1997.

- Bartolomé de Las Casas: Historia de las Indias. 4 volumes, edited by Miguel Ginesta, Madrid 1875, full text and scans of all four volumes available online in the Internet Archive : Volume 1 , Volume 2 , Volume 3 , Volume 4 .

- Bartolomé de Las Casas: Historia de las Indias. 3 volumes, edited by Augustin Millares Carlo and Lewis Hanke, Mexico City 1951.

- Bartolomé de Las Casas: Report on the devastation of the West Indian countries. Insel, Frankfurt / M. 1966. (Reprinted 1990, edited by Hans Magnus Enzensberger, ISBN 3-458-32253-1 ).

- Bartolomé de Las Casas: Concise Report on the Devastation of the West Indian Countries. published by Michael Sievernich , Inselverlag, Frankfurt / Main / Leipzig 2006, ISBN 3-458-34862-X .

First publications

Las Casas had some of his works printed during his lifetime, but these were not intended for publication, but were copied for a narrow readership, including Prince Philip . There were severe penalties for publishing works on "West Indian affairs" without the approval of the Council of India , including the death penalty since 1558. This is how the first publications of his writings outside of Spain were made: 1571 in Frankfurt am Main , 1625 in Tübingen , 1678 in Jena and 1701 in Cologne . The first Spanish edition appeared in Paris in 1822 . According to other sources, Spanish-language editions of the "Concise Report" appeared in Barcelona in 1646 , in London in 1812 , in Philadelphia in 1821, and in Mexico and Guadalajara in 1822 .

Secular and spiritual appropriation

Already the first editions of the abridged report were put into a different context politically or spiritually motivated by changing a title, adding a foreword or afterword. The first publications in Latin America served to legitimize the resistance against the Spaniards in the independence struggle of the Creoles , of all the descendants of the conquistadors. The first Dutch editions were made during the Spanish-Dutch War and served as secular and spiritual propaganda against Spain, as did later German editions during the Thirty Years' War .

Reception in Spain

In Spain, the accusation of being a particularly cruel and bloodthirsty people was met with the term "black legend" ( Leyenda negra ): the Las Casas reports were dismissed as part of anti-Spanish propaganda and falsification of history. In 1660 the Concise Report was banned by the Holy Tribunal in Saragossa . This step was justified by the fact that the descriptions of Las Casas would damage Spain's reputation:

“This book tells of very terrible and cruel acts, unparalleled in the history of other nations, and attributes them to the Spanish soldiers and colonists sent by the Catholic king. In my opinion, such reports are an insult to Spain. They must therefore be prevented. "

The Spanish historian Ramón Menéndez Pidal tried in the middle of the twentieth century to prove that Las Casas must have been insane, and calls him a “megalomaniac paranoid ”.

20th century

In the socialist countries, Las Casas was celebrated as a champion against imperialism . The Summary Report was published in Prague in 1954, in Warsaw in 1956 and in Leipzig in 1958.

In the foreword of the West German edition published by Hans Magnus Enzensberger in 1966, he draws a parallel between the oppression of the Indians by the Spaniards and the treatment of the Vietnamese people by the USA in the Vietnam War .

“The process that began with the Conquista is not over. It is conducted in South America, Africa and Asia. It is not us who are entitled to judge the monk from Seville. Maybe he spoke ours. "

Adoration

- The Mexican city of San Cristóbal de las Casas was renamed in 1848 in honor of the first bishop of Chiapas .

- There are sculptures and monuments in Seville and San Cristóbal de las Casas, for example.

- Las Casas' image adorns the 1 centavo coin of the Guatemalan quetzal .

Memorial days

- Anglican Church : July 20th in Common Worship

- Evangelical Church in Germany : July 31 in the Evangelical Name Calendar

- Evangelical Lutheran Church in America : July 17th in Lutheran Worship

Films, fiction

The life and struggle of Bartolomé de Las Casas has been the subject of several feature films:

- In 1982 Gottfried John played the father in the German TV film The Return of the White Gods (Director: Eberhard Itzenplitz ). Clear references to the present and the theology of liberation were made in this film .

- In 1992 a Belgian-French production followed under the title La Controverse de Valladolid with Jean-Pierre Marielle in the lead role.

- The film Und Then the Rain (directed by Icíar Bollaín , 2010) assembles shooting for a film about the brutality of the Spanish conquest with documentary footage of a current water conflict in a Bolivian city. The protagonists are Bartolomé de Las Casas, Antonio de Montesinos, Columbus and Hatuey .

- narrative

- Reinhold Schneider wrote the story Las Casas before Charles V , published in 1938, Scenes from the time of the conquistadors. This was also made into a film in 1992, under the title Bartolomé de Las Casas ( ORF , written and directed by Michael Kehlmann ).

literature

- Ernst-Wolfgang Böckenförde : History of the legal and state philosophy. Antike und Mittelalter , UTB 2270, Siebeck, Tübingen 2002, pp. 338–351. 440f. (Lit.).

- Josef Bordat: Bartolomé de Las Casas (1484–1566). Missionary, bishop, conscientious objector. In: C.-Th. Müller, D. Walter (Ed.): I don't serve! Conscientious objection in history. Berlin 2008, pp. 15–32 (presentation of his pacifist stance)

- Josef Bordat: Justice and Benevolence. The Bartolomé de Las Casas concept of international law. Shaker, Aachen 2006, ISBN 3-8322-5627-X .

- Josef Bordat: New World Order, Old Resistance. On the topicality of the Dominican Father Bartolomé de Las Casas (1484–1566). In: Cuckoo. Notes on everyday culture. Vol. 20, No. 2, Graz 2004, pp. 10–15 (update of Las Casas' theses on interventionism)

- Mariano Delgado : "Bartolomé de las Casas y las culturas amerindias." In: "Anthropos" Vol. 102, Issue 1 (2007), pp. 91-97.

- Thomas Duve : Las Casas in Mexico. A case of church and state, law and power and the finding of justice in the early modern period. In: Ulrich Falk u. a. (Ed.), Cases from legal history. Munich 2008, 178–196.

- Thomas Eggensperger: The influence of Thomas Aquinas on the political thinking of Bartolomé de Las Casas in the treatise “De imperatoria vel regia potestate”. A theological-political theory between the Middle Ages and modern times. Lit, Münster 2001, ISBN 3-8258-5252-0 (detailed biography and bibliography).

- Thomas Eggensperger, Ulrich Engel : Bartolomé de Las Casas. Dominican bishop defender of the Indians . 2nd Edition. Matthias-Grünewald-Verlag, Mainz 1992, ISBN 3-7867-1547-5 (short biography, short and concise analysis of the political and ideological contrasts of the Conquista, afterword Gustavo Gutiérrez)

- Urs M. Fiechtner , Sergio Vesely: Awakening in the New World. Biography of a novel about Bartolomé de Las Casas and his time. With appendix about the life and work of Las Casas as well as maps and references. Illustrations by Christian Kühnel. Signal, Baden-Baden 1988; Terre des Hommes 2006, ISBN 9783924493684

- Charles Gillen: Bartolomé de Las Casas. Cerf, Paris 1995, ISBN 2-204-05135-7 .

- Matthias Gillner : Bartolomé de Las Casas and the conquest of the Indian continent. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-17-013930-4 .

- Gustavo Gutiérrez : God or the gold. The liberating path of the Bartolomé de Las Casas. Freiburg 1990, ISBN 3-451-21994-8 .

- Patrick Huser: Reason and Domination. The canonical sources of law as the basis of natural and international law arguments in the second principle of the treatise Principia quaedam by Bartolomé de Las Casas. Religious Law in Dialogue Vol. 11, LIT-Verlag, Zurich 2011, ISBN 978-3-643-80080-0 .

- Klaus Kienzler : Las Casas, Bartolomé de OP. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 4, Bautz, Herzberg 1992, ISBN 3-88309-038-7 , Sp. 1186-1190.

- Claudio Lange : Colonialism. Testimony from Bartolomé de Las Casas. Central University Print Shop, Berlin 1972. (Philosophical dissertation)

- Ramón Menéndez Pidal : El padre Las Casas. Su doble personalidad. Espasa-Calpe, Madrid 1963 (tries to disqualify Las Casas as the schizophrenic polluter of the Spanish nation)

- Marianne Mahn-Lot: Bartolomé de Las Casas et le droit des Indiens. Payot, Paris 1982, ISBN 2-228-27390-2 .

- Johannes Meier , Annegret Langenhorst: Bartolomé de Las Casas. The man - the work - the effect . With a selection of texts by Las Casas and an interview with Gustavo Gutiérrez. Frankfurt a. Main 1992, ISBN 3-7820-0651-8 .

- Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. Freiburg 1990, ISBN 3-451-22066-0 .

- Francis Orhant: Bartolomé de Las Casas. Ed. Ouvrières, Paris 1991, ISBN 2-7082-2881-1 .

- Henning Ottmann : History of political thought, Vol. 3/1: The modern times. From Machiavelli to the great revolutions . Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2006, pp. 113–118. 131-133 (lit.).

- André Saint-Lu: Las Casas indigéniste: études sur la vie et l'œuvre du défenseur des India. Ed. L'Harmattan, Paris 1982, ISBN 2-85802-206-2 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Bartolomé de Las Casas in the catalog of the Ibero-American Institute in Berlin

- Literature by and about Bartolomé de Las Casas in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Bartolomé de Las Casas in the German Digital Library

- Literature by and about Bartolomé de Las Casas in the catalog of the library of the Instituto Cervantes in Germany

- Historia de las Indias original text in Spanish

- Brief account of the devastation of the West Indian countries Original text in Spanish

- Corina Bucher, marginalia on: Christopher Columbus, Corsair and Crusader. 2006

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, p. 267.

- ^ Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, p. 252.

- ↑ a b Helen Rand Parish with Harold E. Weidmann, SJ: The Correct Birthdate of Bartolomé de las Casas in: The Hispanic American Historical Review, Volume 56, No. 3, Duke University Press, 1976, pp. 385-403.

- ^ Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, p. 15.

- ↑ a b Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, p. 18.

- ^ Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, p. 22ff.

- ^ Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, p. 34f.

- ↑ a b Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, p. 43ff.

- ^ Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, pp. 46-52.

- ^ Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, p. 51.

- ^ Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, pp. 36-42.

- ^ The Advent Sermon of Antón Montesinos, 1511 at DB University of Münster. Retrieved April 16, 2012.

- ↑ Advent sermon , quoted from Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, p. 41.

- ↑ a b quoted from Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, pp. 91f.

- ^ Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, pp. 52-59.

- ^ Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, pp. 59-71.

- ^ Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, pp. 71-79.

- ↑ quoted from Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, p. 75.

- ^ Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, pp. 79-86.

- ^ Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, p. 107.

- ↑ a b Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, p. 109f.

- ↑ Bartolomé de Las Casas: Obras Completas . Vol. 1: Álvaro Huerga: Vida y Obras , Madrid 1998. ISBN 84-206-4061-1 . Pp. 143-146.

- ^ Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, pp. 111-126.

- ^ Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, p. 125, p. 134.

- ^ Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, pp. 138-150.

- ^ Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, pp. 150-153.

- ^ Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, pp. 155-159.

- ^ Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, pp. 160-165, p. 184.

- ↑ a b c Bartolomé de Las Casas (author), Michael Sievernich (ed.), Ulrich Kunzmann (translator): Brief report on the devastation of the West Indian countries. with an afterword by Hans Magnus Enzensberger, Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / Leipzig 2006, pp. 168ff.

- ↑ a b Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, pp. 189f.

- ↑ Entry on Bartolomé de Las Casas on catholic-hierarchy.org

- ^ Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, p. 197.

- ^ Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, pp. 201-207.

- ^ Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, p. 183, p. 209.

- ^ Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, p. 215.

- ^ Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, p. 225.

- ^ Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, pp. 218-221.

- ^ Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, pp. 226-230.

- ^ Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, p. 232, p. 240.

- ^ Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, pp. 241-243.

- ^ Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, pp. 252-254.

- ↑ Christoph Columbus (author), Ernst Gerhard Jakob (author), Friedemann Berger (ed.): Documents of his life and his travels. Volume I, Verlag Collection Dieterich, Leipzig 1991, p. 33.

- ↑ Julian Gran Berry and Gary Vescelius: Languages of the pre-Columbian Antilles. University Alabama Press 2004, p. 11.

- ^ Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, pp. 89-94.

- ^ Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, p. 229.

- ↑ a b Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, p. 236ff.

- ↑ a b Bartolomé de Las Casas (author), Michael Sievernich (ed.), Ulrich Kunzmann (translator): Brief report on the devastation of the West Indian countries. with an afterword by Hans Magnus Enzensberger, Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / Leipzig 2006, p. 228ff.

- ^ Martin Neumann: Las Casas. The incredible story of the discovery of the New World. 1990, p. 259.

- ↑ Bartolomé de Las Casas (author), Michael Sievernich (ed.), Ulrich Kunzmann (translator): Brief report on the devastation of the West Indian countries. with an afterword by Hans Magnus Enzensberger, Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / Leipzig 2006, p. 236.

- ↑ Bartolomé de Las Casas (author), Michael Sievernich (ed.), Ulrich Kunzmann (translator): Brief report on the devastation of the West Indian countries. with an afterword by Hans Magnus Enzensberger, Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / Leipzig 2006, p. 182.

- ↑ Bartolomé de Las Casas in the Ecumenical Lexicon of Saints

- ↑ 8th edition. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt a. M. 2000 ISBN 3-518-38222-5 . Banned by the National Socialists after the 1st edition. Could not appear again until 1946.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Casas, Bartolome de Las |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Dominican, missionary and writer in the Spanish colonies of America |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1484 or 1485 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Seville |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 18, 1566 |

| Place of death | Madrid |