Tenochtitlan

Tenochtitlan ( Nahuatl , IPA : [ te.noːʧ.'ti.tɬan ] with a long o and emphasis on the cake, Spanish Tenochtitlan ) was from 14 to the early 16th century the capital of the Aztec Empire until it was conquered and destroyed by the Spanish conquistadors .

Probably more than a hundred thousand people lived in the city at the beginning of the 16th century when the first Spaniards arrived there. It was the largest city on the American continent and one of the largest in the world . Its remains are almost completely built over by today's Mexican capital, Mexico City . The few remaining ruins in the modern city center have been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1987 .

The name means "City of Tenoch ". The name Tenōch is in turn formed from te (tl) "stone" and nōch (tli) "prickly pear " (the fruit of Opuntia vulgaris ). The frequently given interpretation as the “city of the stone cactus” is therefore difficult to justify.

location

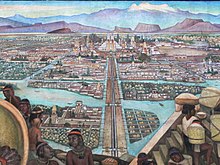

Tenochtitlan was located on several islands in the western part of Lake Texcoco , which lies in the valley of Mexico at an altitude of about 2240 meters. In the north, east and south, the valley is surrounded by a mountain range dominated by the Popocatépetl and Iztaccíhuatl volcanoes . The city was connected to the mainland by five causeways to the north, west and south. On a neighboring island in the north, separated from Tenochtitlan only by a canal, was the initially independent city of Tlatelolco .

Today the Texcoco lake no longer exists in its former extent, as it was gradually drained by the Spaniards. Only in Xochimilco in the south of today's Mexico City are small bodies of water still forming a last remnant of the lake.

Building the city

The islands on which Tenochtitlan and Tlatelolco were located took up a total of around 13 square kilometers. The city was connected to the mainland by five dams made of stone and earth. They had several interruptions that were closed by movable wooden bridges. The Aztecs took advantage of this fact especially in 1521 when they defended their city against the Spaniards. Since Tenochtitlan could only be reached via the causeway and the sea route, it had no city wall.

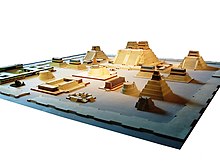

Coming from the north, west and south, the causeways flowed in front of the Templo Mayor onto the large market square of Tlatelolco and the square in front of the Templo Mayor in Tenochtitlan. This formed the center of the city. The palaces of the rulers Moctezuma I , Axayacatl and Moctezuma II were built around the square in the course of Aztec history . The main streets running at right angles to each other simultaneously divided Tenochtitlan into the four districts of Moyotlan, Zoquiapan, Atzacualco and Cuepopan, which in turn were divided into smaller districts. The traffic within the city moved on a labyrinth of alleys and canals. In addition to the dam roads, the port in the east of Tenochtitlan was also used for trade with other settlements.

The often multi-storey houses of the lower social classes stood tightly packed; a part was built as pile dwellings . The residential properties, especially in the outer parts of the city, often had a fenced-in garden. Behind them were the so-called chinampas , fields that were often only a few meters wide, but very long in relation to their width. The Chinampas were cultivation areas that were obtained from the swampy soil and which, due to their favorable soil moisture, often enabled several harvests a year. Nevertheless, the Chinampas alone were not enough to feed the steadily growing population of Tenochtitlan. In addition, with the expansion of the city and the Aztec Empire, land ownership became more and more a privilege of the nobility. However, the proportion of the higher class in the population was relatively high.

The extensive temple area was of outstanding importance. Around the Templo Mayor, several larger and smaller temples were grouped, which were dedicated to different deities and certain cults of individual social classes. Furthermore, there was a specially created space for the ritual ball game in the temple district .

The northern part of the city was formed by the independent city of Tlatelolco until 1473 . The settlement was already closely connected to Tenochtitlan before its conquest and was an economic center of the region. After the subjugation of the Tenochtitlan residents, Tlatelolco retained this character for the most part; even the Spaniards were impressed by the size and variety of the Tlatelolco market. When the Spaniards arrived, tens of thousands of people, possibly even more than 150,000, were likely to have lived in the two cities that were now united. Tenochtitlan would have been one of the largest cities in the world at that time.

story

Foundation and first years

According to legend, the origin of the Aztecs lies in a place called Aztlán , the exact location of which is unknown. From there they hiked on the instructions of their god Huitzilopochtli in a south-westerly direction until, after a few intermediate stops, they reached the Valley of Mexico. The priests prophesied there that one should settle where an eagle sits on an opuntia and fights with a snake. The place was finally found on an island in the western part of Lake Texcoco, where the city was built under the mythical leader Ténoch . Tenoch is a figure derived from the place name.

The time of the first Aztec settlement can be dated between 1320 and 1350. Presumably, however, there was already a settlement at this point. A few years after it was founded, another settlement, Tlatelolco , was established on an island north of the city . Although both places acted together politically again and again, there was sometimes hostility until the ruler of Tlatelolco, Moquixhuix, was killed in 1473 and the city was ruled from Tenochtitlan.

King Acamapichtli , who ruled towards the end of the 14th century, can be identified as the first historically secured ruler . Already under his successor Huitzilíhuitl the integration of the young city into the local power structure began, because he married the daughter of the ruler of Tlacopan , whereby among other things a certain equality with other cities was established through the issuing of tribute obligations.

Securing the hegemony of Tenochtitlan

Chimalpopoca , Huitzilíhuitl's son, ascended the throne of Tenochtitlan as a youth, but was murdered at the instigation of Maxtla , the ruler of Azcapotzalco . In Chimalpopoca's place came his uncle Itzcóatl , who now subjugated Maxtla as well as the rulers he appointed in other cities. This only succeeded after a war in the course of which Texcoco and the Tepanec capital Azcapotzalco were conquered. After the war, the now allied cities of Tenochtitlan, Tlacopan and Texcoco pledged their mutual loyalty and formed the so-called Aztec Triple Alliance . With the defeat of the Tepaneks, the Aztec supremacy over the valley of Mexico was finally secured.

During the reign of the Itzcoátl, there were also far-reaching changes in Tenochtitlan. By building a drinking water aqueduct and the three dams, the connection to the mainland was strengthened on the one hand, and the drinking water supply of the growing city was secured on the other. At the same time, land ownership increasingly became a privilege of the nobility and thus a symbol of power. In addition, many old illuminated manuscripts were destroyed on Itzcóatl's instructions; the reason for this is controversial in modern research. A relatively probable reason for the burning of the manuscripts was probably to legitimize the existing relations of rule and thus the existence of one's own dynasty.

After Itzcóatl's death in 1440, Moctezuma I came to power. Several natural disasters occurred during his reign: between 1446 and 1450 there was a plague of locusts, a flood and a famine. The latter event in particular caused many residents to leave the city. Although a 16-kilometer-long dike was built across the lake east of Tenochtitlan to prevent further flooding, it had become evident that the city could no longer feed its residents on its own. Moctezuma therefore undertook campaigns south to subjugate the city-states there and to impose tributes on them.

Domestic and foreign policy consolidation of hegemony

Who came to the throne of Tenochtitlan directly after Moctezuma's death in 1469 is not known for sure. However, in 1471, after long negotiations, an agreement was reached on Axayacatl , a grandson of Itzcóatl. In 1473 he finally subjugated the neighboring city of Tlatelolco , which then merged more and more with Tenochtitlan and was completely part of Tenochtitlan until the Spanish conquest of Mexico . With the conquest of the city, the Aztecs also gained control of an important trading center in the Valley of Mexico.

Under Axayacatl's brother Tízoc , a massive expansion of the Templo Mayor began, which was the central temple of the city and was dedicated to the gods Tlaloc and Huitzilopochtli . On the occasion of its solemn inauguration, which was already carried out by the next King Auítzotl , possibly up to twenty thousand people who had been taken as prisoners of war during the previous campaigns of the ruler were sacrificed for four days. Among other things, Auítzotl succeeded in subjugating the distant province of Xoconochco on today's border between Mexico and Guatemala. When trying to build another aqueduct from a lake southwest of the city into Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital was flooded and largely destroyed. The water pipe had to be abandoned; in Tenochtitlan itself an almost complete rebuilding was necessary.

Reign of Moctezuma II and destruction of the city by the Spaniards

In 1502 Moctezuma II became king of the Aztecs. He undertook some campaigns to the north and to the southern Oaxaca region to strengthen Tenochtitlan's economic position. However, the new ruler also deliberately widened the gap between the nobility and the people, as he dismissed many non-aristocrats from civil service. However, Moctezuma is best known for its role in the conquest of Mexico by the Spaniards. He accepted that the Spaniards could settle in Tenochtitlan in 1519 and allowed them to force him into a puppet role. During a rebellion during which Moctezuma was killed, the Spaniards and their Tlaxcaltec allies were driven out of the city with great losses, but they returned with reinforcements from their homeland a few months later. Many residents died of starvation and diseases brought in during the siege that followed . The conquistadors used ships and cannons to prevent the city from being supplied with canoes across the lake. During the frontal attack on the causeways, the defenders involved the Spaniards in bitter house-to-house fighting . The invaders tore down almost every house in Tenochtitlan and were finally able to break the resistance in Tlatelolco on August 13, 1521. The last King Cuauhtémoc was captured in a canoe while on the run.

After the victory, Hernán Cortés allowed the residents to move freely. Soon after the city was conquered, repairs to the roads began and the water supply was also restored. The canals were filled in with the rubble from the demolished houses. The Spaniards allowed residents to return to the ruined city after two months, while settling themselves in the center of the former Aztec capital. But instead of restoring the old houses, they built new buildings from the rubble of the ruins. This is how the Palace of the Spanish Viceroys was created from the remains of the Palace of Moctezuma and the cathedral on the site in front of the Templo Mayor . With the establishment of the viceroyalty of New Spain in 1535, Tenochtitlan was finally renamed the capital of the new viceroyalty and Ciudad de México ( Mexico City ).

exploration

Most of what we know about Tenochtitlan comes from accounts of the conquistadors, monks, and Indian writers of the 16th and 17th centuries. Since the city was rebuilt on the rubble immediately after the conquest, the material remains are completely covered by the modern city, archaeological excavations are therefore only possible in the few free spaces and in connection with new buildings. In a few places you can see parts of the Aztec building mass in today's buildings, but most of the old city is likely to have been irretrievably lost. However, the road and canal network of Tenochtitlan has largely been preserved in the modern streetscape of the city center.

Reconstruction through analysis of the cityscape

A good example of the constancy of the street scene is the location of the four temples in the Tenochtitlan district. They are still clearly visible in the modern cityscape, including the access roads and small squares leading to them:

- Zoquiapan - Plaza San Lucas

- Moyotla - Calle Victoria

- Cuepopan - Calle Obispo

- Atzacualco - Plaza del Estudiante

Accidental finds

Over the centuries there have been numerous accidental finds of Aztec relics, particularly stone monuments and ceramic depots. These include the monumental figure of the goddess Coatlicue found near the southwest corner of the Palacio Nacional and the "Teocalli de la Guerra Sagrada", a stone monument in the form of a temple pyramid, on the back of which a representation of the scene with the eagle on the cactus can be seen, and the sunstone .

The first systematic, small-scale excavations were not carried out until the beginning of the 20th century. Further excavations were carried out through work on supply lines (electricity, sewerage) or the underground lines crossing the city center (in particular line 2, which bypasses the Zócalo in the east and north and almost touches the Templo Mayor, and line 8 in the area of the Theater "Palacio de Bellas Artes") triggered. During the construction of the Pino Suárez station at the intersection of lines 1 and 2, a small round temple was cut, which was probably dedicated to the wind god Ehecatl . It was reconstructed and incorporated into the station through rescheduling. Other finds in the area around the Zócalo were recovered as blocks and transported to the museum. The tight schedule of the construction work makes the archaeological investigation considerably more difficult.

Scheduled excavations

In addition to the extensive development of the city center, the archaeological investigation is hampered by the geological conditions: the entire city center and large parts of the city beyond are built on the soil of Lake Texcoco, which was drained in the 16th century. The deep sediments of the sea floor mean that the old surface is several meters below the modern one and mostly in the area of the groundwater. An artificial lowering of the groundwater level required for excavations would jeopardize the stability of neighboring buildings. The effects of the precarious soil conditions can be seen particularly well in the cathedral on the Zócalo, which slopes to the west, while the immediately adjacent Babtisterio sinks to the east. Numerous churches in the city center are already around 2 m below street level. Larger pre-Hispanic buildings are sometimes marked out by hills in the course of the road.

Main temple of Tenochtitlan

The location of the old main temple was roughly known since smaller uncoverings at the beginning of the 20th century near the corner of the streets "República de Argentina" and the now abandoned part of the street "República de Guatemala". However, the dense development had prevented further excavations. The accidental discovery of a large relief depicting the dead goddess Coyolxauhqui was used in 1978 to initiate the “Proyecto Templo Mayor”. The aim of the project, led by the Mexican archaeologist Eduardo Matos Moctezuma , for which a number of houses had to be demolished, was the complete excavation of the remains of the main temple of Tenochtitlan.

During the excavations from 1978 to 1982 at least seven construction phases of the main temple, which had been expanded again and again, as well as a number of auxiliary buildings were uncovered. From the most recent construction phase of the temple, which the Spanish conquerors had encountered and destroyed, only small remains have been preserved. The presumed earliest construction phase, which according to the legends would correspond to the earth altar erected at this point, was not sought, as it was probably difficult to find and also too deep in the area of the groundwater. The assignment of the construction phases to individual rulers and thus their dating are hypothetical. The extremely large amount of finds comes from the last two centuries before the Spanish conquest. Many of the archaeological finds can now be viewed in the National Museum of Anthropology ( Museo de Antropología in Spanish ) and in the new Museo del Templo Mayor located directly behind the excavation area .

A building complex was uncovered north of the main temple, which apparently represents meeting rooms for dignitaries or warriors. In it, brick benches run along the walls, the shape and decoration of which are very clearly reminiscent of corresponding constructions in the columned halls of Tula and must be inspired by them.

Also under the cathedral built by the Spaniards, remnants of buildings in the forecourt of the temple have been found since the 1970s during construction work to stabilize the building, which sank into the soft ground, but these cannot be reliably assigned.

The model of the temple area exhibited in various places goes back to studies by the Mexican archaeologist Ignacio Marquina , who was guided solely by the written reports, and is now in many parts overtaken by the excavations.

center

One block north of the cathedral (Calle Donceles) in 2008 during rescue excavations for the construction of a new building, the more than 5 m deep foundations of two buildings, one of which is interpreted as calmecac . It is a columned hall supported by masonry pillars and accessible via a staircase in the south with a masonry bench running along the rear wall. In the area of the building, several “buried” roof battlements made of fired clay in the form of a sliced snail were found, as well as a large sculpture of a cuauhxicalli in the shape of an oversized eagle.

literature

Non-fiction

- Hanns J. Prem : The Aztecs. History - culture - religion. Verlag CH Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-406-45835-1 .

- Felipe Solis Olguin, Eduardo Matos Moctezuma: Aztecs. Royal Academy of Arts, London 2002, ISBN 1-903973-13-9 . (English)

- David E. Stannard: American Holocaust. The conquest of the New World. Oxford University Press, New York 1993, ISBN 0-19-508557-4 . (English)

- Charles C. Mann: 1491. New revelations of the Americas before Columbus. Alfred A. Knopf, New York 2005, ISBN 1-4000-4006-X . (English)

- José Luis de Rochas: Tenochtitlan: Capital of the Aztec Empire. University Press of Florida, 2012, ISBN 978-0-8130-4220-6 . (English)

Literary receptions

- José León Sánchez: Tenochtitlan. The last battle of the Aztecs. (Original title: Tenochtitlan - La última batalla de los aztecas. ) Unionsverlag Taschenbuch, Zurich 2004, ISBN 3-293-20306-X .

- Gary Jennings: The Aztec. (Original title: AZTEC. ) Fischer Taschenbuchverlag, Frankfurt am Main 2004, ISBN 3-596-16522-9 .

- Colin Falconer: The Aztecs. (Original title: Feathered Serpent. ) Heyne 1997, ISBN 3-453-12338-7 .

Web links

- The fall of the Aztecs - June 30, 1520 - The sacrificial cult of the Aztecs Horrible finds and terrible reports from February 22, 2007.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Ursula Dyckerhoff , Hanns J. Prem : Toponyms and ethnonyms in Classical Aztec. Verlag von Flemming, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-924332-06-1 .

- ↑ a b Heinrich Pleticha (Ed.): World history in 12 volumes. Volume 7, Bertelsmann Lexikon Verlag, Gütersloh 1996, p. 73.

- ^ Hanns J. Prem: The Aztecs. History - culture - religion. (= Beck'sche Reihe. C.-H.-Beck-Wissen. 2035) 4th revised edition. CH Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-406-45835-1 , p. 34.

- ↑ Bernal Díaz del Castillo : History of the Conquest of Mexico. (= Insel-Taschenbuch. 1067) Edited and edited by Georg A. Narciß. Insel-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-458-32767-3 , pp. 215ff. (Original Spanish title: Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España . )

- ^ Hanns J. Prem: The Aztecs. History - culture - religion. 4th revised edition. CH Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-406-45835-1 , p. 29.

- ^ Hanns J. Prem: The Aztecs. History - culture - religion. 4th revised edition. CH Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-406-45835-1 , p. 76.

- ^ Hanns J. Prem: The Aztecs. History - culture - religion. 4th revised edition. CH Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-406-45835-1 , p. 77.

- ^ Hanns J. Prem: The Aztecs. History - culture - religion. 4th revised edition. CH Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-406-45835-1 , p. 86.

- ^ Hanns J. Prem: The Aztecs. History - culture - religion. 4th revised edition. CH Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-406-45835-1 , S, p. 94.

- ↑ Geoffrey Parker (Ed.): The Times - Great Illustrated World History. Verlag Orac, Vienna 1995, p. 268.

- ↑ Bernal Díaz del Castillo: History of the Conquest of Mexico. 1988, p. 501.

- ↑ Bernal Díaz del Castillo: History of the Conquest of Mexico. 1988, p. 525.

- ^ Raúl Barrera Rodríguez, Gabino López Arenas: Hallazgos en el recinto ceremonial de Tenochtitlan. In: Arqueología mexicana. 16, 93, 2008, ISSN 0188-8218 , pp. 18-25.

Coordinates: 19 ° 26 ′ 6 ″ N , 99 ° 7 ′ 53 ″ W.