Opuntia

| Opuntia | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Opuntia echios isnativeto the Galápagos Islands . It belongs to the large, tree-like growing Opuntia species. |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Opuntia | ||||||||||||

| Mill. |

The Opuntia ( Opuntia ) are a genus of plants from the cactus family (Cactaceae). With around 190 species it is one of the most species-rich genera within the cactus family. Their distribution area covers large parts of North and South America including the Caribbean . With almost half of the species, the main focus of distribution is in Mexico . The Aztec legend of the founding of Tenochtitlán , which describes how an eagle sits on an opuntia and fights with a snake, is still reflected today in the Mexican coat of arms .

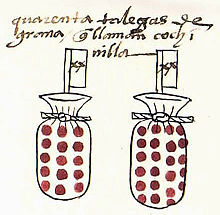

The use of some types of opuntia can be traced back to the time of the Paracas culture . In addition to the use of the shoots and fruits as food, Opuntia were cultivated in particular to obtain the dye cochineal red . In recent years, Opuntia be strengthened in several countries as a feed grown. As invasive neophytes , some Opuntia species spread so widely in different areas that they had to be fought with biological means.

description

Vegetative characteristics

Opuntia grow shrubby to tree-like, are erect or creeping and occasionally form piles or mats. They are often richly branched and can reach heights of 10 meters and more. Some species have a well-developed, elongated, round trunk that is recognizable at the beginning and appears continuous as it ages. The individual shoot sections, often called limbs, are noticeably connected to one another. The green or sometimes reddish to purple shoots consist of flattened, leaf-like segments ( platycladia ) that are round, egg-shaped, elliptical, cylindrical or rhomboid in shape. Their bald or finely hairy surface is almost smooth to bumpy. They are 2 to 60 (rarely 120) inches long and 1.2 to 40 inches wide.

The usually elliptical, round or inverted egg-shaped areoles in the leaf axils are 3 to 8 (rarely 10) millimeters long and 1 to 7 (rarely 10) millimeters wide. They are woolly white, gray or yellow-brown to brown. The areole wool turns white or gray to black with age. The small, sessile, fleshy leaves formed by the areoles are cylindrical to conical and fall off early. Glochids either arise only at the edge of an areole or form tufts. They are initially white, yellow to brown or red-brown and later become white to brown or red-brown. The up to 15 (or more) needle-shaped to awl-like thorns , which can also be missing, are oblong to round to angular-flattened in cross section and are up to 75 (rarely 170) millimeters long. The thorns are white, yellow to brown, reddish brown to gray or black in color and become gray to dark brown to black with age. Sometimes they are yellow or paler in color at the tips.

blossoms

With a few exceptions (for example Opuntia stenopetala and Opuntia quimilo ), the bisexual and radial symmetry flowers arise at the edges of the shoot sections. They usually stand alone and are of variable color. The outer tepals are green to yellow and tinted at the edges with the color of the inner tepals, which are pale yellow to orange and pink to red or purple in color. The flowers are rarely white or have a different color at the base. The pericarpel is spherical to top-shaped and covered with areoles and leaf-like scales. One flower tube is missing.

The stamens are usually yellow or green and circular or spiral around the stylus arranged. They show a pronounced thigmotaxis . In response to a touch stimulus, they curve in the direction of the stylus and enclose it. The stylus is simple, hollow, and usually green or yellow, but can also be pink, red, or orange. The broad-leaved stigma protrudes over the stamens. The unicompartmental ovary contains several hundred ovules .

Fruits and seeds

The non-bursting, occasionally stalked fruits stand individually, sometimes in clusters and are club-shaped to cylindrical, egg-shaped or obovate to almost spherical. They are 10 to 120 millimeters long and 8 to 120 millimeters wide. They consist of the closed hypanthium , which contains the pulp (pericarp) and the many seeds embedded in it (acrosarcum, false fruit ).

The fruits have a smooth or bumpy surface and can be thorny, sometimes strong, and have glochids . They are fleshy to juicy or dry. Fleshy fruits are green, yellow or red to purple, dry fruits yellowish brown to gray in color.

The fruits contain few to many, white to brown seeds that are noticeably flattened on the sides. The seeds are circular to kidney-shaped. They are 3 to 10 millimeters long. The small seed coat is bald or finely haired.

Genetics and age

The base chromosome number of the genus corresponds to that of all cactus plants. Polyploidy is common in the Opuntia, as in all genera of the subfamily of the Opuntioideae.

The only fossil remains of the cactus family have been discovered in the rat waste heaps of the American bush rats . The remains, dated to an age of around 24,000 years using the C-14 method , come from a cylindrical opuntia.

Life cycle

The seeds of Opuntia, for example Opuntia stricta , can germinate for up to 15 years . For a successful germination the seeds need a dormancy of usually at least one year. In order to circumvent this and also to enable freshly collected seeds to be sown, more or less successful attempts have been made to treat the seeds mechanically or with acids. A few days to several weeks pass from sowing to germination. The seedlings can show a considerable increase in length, so seedlings of Opuntia echios grow up to 25 centimeters in the first year. Opuntia seedlings are part of the diet of many herbivores and require the protection of other opuntia or perennial plants under which they can grow in order to survive.

In contrast to all other genera of the cactus family, either cladia or flowers can develop from the meristem of an areole . It takes between 21 and 47 days for a flower bud to develop until it blooms (a maximum of 75 days). It takes between 45 and 154 days for the fruits to ripen. The longest ripening time was observed for Opuntia joconostle and was 224 days. The fruits are eaten by animals who spread the seeds with their excretions.

ecology

pollination

The flowers of the opuntia are frequented by numerous hymenoptera , some beetles , two species of butterflies and ten species of birds , but not all of them contribute to pollination . Most opuntia are pollinated by bees , since the opuntia flowers are particularly well adapted to these pollinators ( melittophilia ). In order to collect pollen from the lower anthers , the bees run along the stylus , thereby pollinating.

The majority of pollinating hymenoptera are polylectic and therefore do not specialize in any one plant family. The genera Ashmeadiella , Diadasia , Melissodes and Lithurge , on the other hand, are exclusively hymenoptera specialized in opuntia ( oligolectic ). It is assumed that the genera Diadasia and Lithurge developed together with the Opuntia ( coevolution ).

Some of the Galapagos Islands spread Opuntienarten be through to the Darwin's finches belonging ground finches Opuntias finch , sharp-beaked ground finch and cactus finch ( Geospiza scandens pollinated). For pollination of Opuntia quimilo and Opuntia stenopetala are hummingbirds responsible.

In the case of the opuntia, both self-pollination (with the pollen of its own flower) and cross- pollination (with the pollen of another flower of the same plant) and xenogamy (with the pollen of another plant) have been demonstrated.

Agamospermia

Opuntia often form seeds without prior fertilization ( agamospermia ). Mostly these are adventitious embryos formed from nucellus tissue ( sporophytic agamospermia ). In Opuntia streptacantha , diplosporia was found , in which an embryo is formed from an unreduced egg cell.

Spread

Opuntia do not depend on certain animal species to spread. Depending on the distribution area, these can be small or large mammals, birds, lizards or turtles that eat the fruits of the opuntia. In the South African Kruger National Park , for example, baboons and elephants have been identified as spreading Opuntia stricta . The opuntia native to the Galápagos Islands are distributed among others by the Galápagos rat ( Oryzomys bauri ). In the stomach of the animals, the hard seed coat is attacked by the digestive juices and thus the germination capacity of the seeds is increased ( digestive spread ). In the Mexican highlands of San Luis Potosí , one of the main spreaders of the opuntia native to there is the genus Pogonomyrmex ( ants spread ).

Opuntia spread not only through seeds, but also through vegetative reproduction . The flax shoots of many Opuntia species can be separated from one another relatively easily. If they fall to the ground, the areoles first develop adventitious roots and finally a new plant. Opuntia fragilis is likely the only way to spread in this way. Rarer forms of spreading use an existing rhizome ( e.g. Opuntia megarhiza ) or aboveground or underground runners (e.g. Opuntia polyacantha ).

Distribution and locations

The distribution area of the Opuntia stretches from the south of Canada , where Opuntia fragilis, the most northerly widespread cactus species grows, to the south of Argentina . It extends from the Caribbean in the east to the Galápagos Islands in the west. Mexico is the main distribution area with around 75 species. Opuntia are naturalized in many countries, for example in the Mediterranean area , South Africa or Australia .

Opuntia grow in arid and semi-arid, as well as in temperate and tropical areas, at altitudes that range from sea level to an altitude of 4700 meters. Some species, such as Opuntia howeyi , are extremely frost-resistant and even hardy in Central Europe .

Systematics

The opuntia are the most species-rich genus within the subfamily Opuntioideae , which differs from the other subfamilies of the cactus family by the presence of glochids and a hard, bony seed coat . The genus of Opuntia was established by Philip Miller in 1754, one year after the introduction of binary nomenclature . The type species of the genus is Cactus ficus-indica .

There is little reliable knowledge about many species of Opuntia. This applies above all to the species found in southern Mexico, the Caribbean and South America. The taxonomic situation is made more difficult by the fact that opuntia easily form hybrids with one another and numerous forms have formed in the species cultivated by humans .

According to Edward F. Anderson (2005), the following species, subspecies and varieties belong to the genus Opuntia:

|

|

|

The following natural hybrids are also known:

|

Synonyms of the genus are Nopalea Salm-Dyck , Phyllarthus Neck. ex M.Gómez . Platyopuntia Frič , Chaffeyopuntia Frič , Clavarioidia Frič & Schelle , Clavatopuntia Frič & Schelle , Salmiopuntia Frič , Subulatopuntia Frič & Schelle , Parviopuntia Soulaire , Plutonopuntia P.V.Heath and Salmonopuntia P.V.Heath .

Etymology and symbolism

etymology

In chapter 12 of the first book of De historia plantarum libri decem , Theophrastus of Eresos described a plant that grew near the Greek city of Opus in the ancient region of Lokris Opuntia , in the area of today's prefecture of Fthiotida . About two hundred years later, Pliny the Elder reported :

"Circa Opuntem est herba etiam homini dulcis, mirumque e folio eius radicem fieri ac sic eam nasci."

“The herb Opuntia , which is also a lovely food for humans, grows around Opunt . It is strange that the leaves take root and that the plant reproduces in this way. "

The plant mentioned by Theophrastus and Pliny was not a cactus plant. Joseph Pitton de Tournefort used the name Opuntia for the genus he established in 1700, as the opuntia shoots, often incorrectly referred to as “leaves”, have the property of taking root as soon as they are laid on the ground.

symbolism

Opuntia are closely linked to the founding of Tenochtitlán ( city of the stone cactus ) by the Aztecs , who, according to a prophecy, settled after their departure from Aztlán where an eagle perched on an opuntia and fought with a snake. In the seal of Mexico , this legend reflects today.

In Malta , the naturalized Opuntia ficus-indica is widespread and is used to make a liqueur. The importance of this opuntia led to it being part of the Maltese national emblem from 1975 to 1988 .

Botanical history

Numerous Aztec codices contain representations of opuntia and other cacti and succulents. The Codex Badianus compiled by Martin de la Cruz and Juan Badiano in 1552 , for example, contains a true-to- detail colored drawing of an opuntia known as Tlatocnochtli . In addition to the 13 varieties listed, they also gave a recipe for the treatment of burns, which contained an opuntia juice as an ingredient. In his Codex Florentinus, completed in 1569, Bernardino de Sahagúns also reported on the cultivation and use of opuntia by the Aztecs.

The first opuntia probably came to Europe shortly after the discovery of America . The oldest European illustrations of the Opuntia can be found in Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo's work Historia General y Natural de las Indias, Islas y Tierra Firme del Mar Océano from 1535. In it he described the use of the opuntia for wine production and dye extraction. Giovan Battista Ramusio's collection of travelogues Delle Navigationi e Viaggi (Venice 1556) also contains an illustration of an opuntia. In his comments on Pedanios Dioscurides De Materia Medica , Pietro Andrea Mattioli referred to the medical use of the opuntia in 1558. In 1571 Matthias de L'Obel and Pierre Pena mentioned in their description of the “Indian fig tuna” that the plant grew in Spain , France , Italy and that it was cultivated by pharmacists in Belgium . Francisco Hernández , who explored the viceroyalty of New Spain for seven years from 1570 on behalf of the Spanish King Philip II , already distinguished six types of Nochtlis (Tunas): Iztacnochtli , which was known to the Spanish as "Indian fig" (higuera de las indias) , Coznochtli , Tlatonochtli , Tlapalnochtli , Tzapnochtli and Zacanochtli .

The name Opuntia was first used in 1700 by Joseph Pitton de Tournefort for a genus of plants. In Institutiones Rei Herbariae he listed a total of 11 species after a brief genus diagnosis . When Carl Linnaeus in 1753 for his work Species Plantarum worked the cactus, he rejected the old introduced generic Cereus , Melocactus , Opuntia and Pereskia and led all cacti under the generic name Cactus , including the Opuntia Opuntia cochenillifera ( Cactus cochenillifer ), Opuntia curassavica ( Cactus curassavicus ), Opuntia ficus-indica ( Cactus ficus indica and Cactus opuntia ) and Opuntia tuna ( Cactus tuna ). Just a year later, Philip Miller reintroduced the generic name Opuntia . Miller did not yet use the binary nomenclature introduced by Linnaeus for his 14 species , but rather the previously common descriptive Latin phrases. For example, Opuntia ficus-indica was described with the phrase Opuntia articulis ovato-oblongis, spinis setaceis (Opuntia with elongated oval limbs and bristly thorns). It was not until 1768 that Miller introduced the binomials in his work.

In 1856, when describing 50 American opuntia, George Engelmann subdivided the genus into the sub-genera Stenopuntia , Platopuntia , and Cylindropuntia for the first time . In the first complete scientific study of the cactus family, published by Karl Moritz Schumann at the end of the 19th century, 131 species of Opuntia are already listed. When Nathaniel Lord Britton and Joseph Nelson Rose published the first volume of The Cactaceae in 1919 , they believed the genus already comprised at least 250 species. From the literature, however, they knew more than 900 names that were supposed to belong to the Opuntia, but were not or insufficiently described. During their processing, they established new genera for some species of Opuntia or accepted them again ( Nopalea , Maihuenia , Pereskiopsis ). Other genera ( Tephrocactus , Consolea ), however, became part of the Opuntia with them. In 1958 Curt Backeberg , like Friedrich Ritter (1980) later, split the extensive genus of Opuntia into further genres.

1958 began by Gordon Douglas Rowley with the inclusion of different individual genera in the Opuntia the opposite trend towards a large collective genus, which lasted until 1999. Roberto Kiesling (* 1941) made a proposal in 1984 to separate different species from the Opuntia into their own genera. For a long time, these considerations were rejected by the Cactaceae Working Party of the International Organization for Succulent Research . In 2001, studies of the DNA and the morphology of seeds, pollen and thorns confirmed that such a broad concept of the genus is polyphyletic and cannot be sustained.

use

Use as a coloring agent

Carmine-producing cochineal scale insects

Since around 1100 the Aztecs have been growing "Nochtli" plants ( Opuntia cochenillifera ) on large plantations in order to produce the dye carmine . Their heads wore bright crimson robes with which they impressed the Spaniards. The process for the production of red textiles could already be proven in the much older Paracas culture .

The Spanish conquerors quickly recognized the commercial value of the dye. They closely guarded the secret of its production and have been successful for many decades. It was Nicolas Hartsoeker who first published an enlarged illustration of a cochineal scale insect in Essai de dioptrique in 1694 . Ten years later, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek studied the scale insects responsible for color production (especially Dactylopius coccus ) very carefully and was able to finally clarify that it is not the opuntia but the insects that live on them that are necessary for the production of the color. In 1776, Nicolas Joseph Thiéry de Ménonville traveled to Mexico on behalf of the French government to spy out the details of dye production. He succeeded in executing opuntia shoots with cochineal whiteflies, which he was able to reproduce successfully in Port-au-Prince in Haiti.

Other types of opuntia are also suitable as host plants for the cochineal scale insects. Large plantations of Opuntia ficus-indica emerged on the Canary Islands and are still used today for dye production. It takes 140,000 insects to produce 1 kilogram of carmine powder. The insects are killed by heat and then dried. Although the dye obtained from insects has lost its importance due to the production of equivalent synthetic dyes, it is still produced in Mexico , Chile , the Canary Islands and various African countries. The main part is produced in Peru . Naturally produced carmine, for example, is used to color food, luxury goods and cosmetic products.

Opuntia fruits

The fruits of Opuntia schumannii are used in the north of South America to color ice cream and fruit juices . Ropes made from hemp fibers are colored red with the fruits of Opuntia dillenii . Opuntia polyacantha and Opuntia humifusa were used as dressings by the Absarokee , Dakota and Pawnee .

Use as animal feed

During the Spanish colonial rule, livestock, especially sheep and goats, were imported into Mexico on a large scale. In the arid regions, the animals were often poorly supplied with water and grass by the farmers and therefore roamed freely to support themselves. It was observed how the cattle fed on opuntia, among other things. In order to take care of the animals during dry seasons, farmers in Mexico started growing opuntia specifically as fodder in the 19th century.

As CAM plants , opuntia can produce about five times more biomass than C3 plants and three times more than C4 plants from the precipitation available in the arid and semi-arid areas . Opuntia have a high calorific value and are rich in water, vitamins, carbohydrates and calcium. The disadvantage is the lack of proteins , which has to be compensated for by suitable additional feeding, for example with straw.

At the end of the 20th century, about 900,000 hectares of opuntia were grown worldwide for use as animal feed . In comparison, the cultivation area used for the exploitation of the opuntia fruits was only around 100,000 hectares. Forms of Opuntia ficus-indica are mainly used for cultivation . In addition to Mexico, opuntia are used for agriculture in Ethiopia , Brazil , Chile , South Africa and the United States, among others . According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, the importance of the opuntia as animal feed will continue to gain in importance in the future.

Other use

The young and still soft shoot sections (nopalito) are eaten cooked as vegetables or salad, especially in Mexican cuisine. The fruits (tuna) are consumed as fresh fruit. They are used in the manufacture of pharmaceutical and cosmetic products as well as in the treatment of diseases such as diabetes , arteriosclerosis , hypercholesterolemia , heart disease , obesity , colon cancer and gastric ulcers . The fruits of Opuntia ficus-indica are edible and can be eaten peeled raw or made into juice.

When manually harvesting the shoots and fruits of the opuntia, the glochids attached to them can cause dermatitis , which is often referred to as Sabra dermatitis.

Opuntia as a weed

As invasive neophytes , some species of opuntia spread so widely in the Mediterranean region, Australia, India, South Africa and Hawaii that they were viewed as weeds and controlled accordingly. Due to the distinct ability of the Opuntia to reproduce vegetatively, the plants could not be removed simply by plowing them under. First attempts at biological weed control were made in northern India in 1863. The scale insect species Dactylopius ceylonicus , originally mistakenly imported from Brazil in 1795, was actually intended to be used for the production of Cochinelle red. It later proved to be an effective remedy against the Opuntia vulgaris introduced from South America . The successful use of this scale insect is considered to be the first documented example of biological weed control.

Opuntia stricta served in Australia in 1832, about 125 kilometers northwest of Sydney , as a hedge for the local vineyards and was planted as an ornamental plant in Sydney seven years later. However, the plants quickly grew wild and became a nuisance. By 1883 the problem was so great that the Australian government passed legislation to combat it. When Opuntia ficus-indica was introduced as a potential forage crop in1914, the problem only got worse. Mainly in Queensland around 1925 about 25,000,000 hectares were overgrown by opuntia and could no longer be used for agriculture. From 1920 to 1935 studied entomologist in the US, Mexico and Argentina for natural enemies of the prickly pears. Of the 150 species found, 52 were introduced to Australia. Twelve successfully established themselves there. The larvae of the cactus moth ( Cactoblastis cactorum )introduced in 1925destroyed around 90 percent of the opuntia population within less than 10 years.

In South Africa were in 1932 to fight the thorny form of Opuntia ficus-indica , the scale insect Dactylopius opuntiae , Metamasius spinolae from the family of weevils and Cactoblastis cactorum introduced. Unlike in Australia, Dactylopius opuntiae proved to be the most effective here. Introduced to Hawaii, Opuntia megacantha became a problem , particularly at the Parker Ranch . In the 1940s, Dactylopius opuntiae and Cactoblastis cactorum were also used to combat this.

In 1989, Cactoblastis cactorum was first found in the Florida Keys . From there, the moth spreads further and today threatens the opuntia cultures in the southern United States and Mexico as a pest .

Opuntia can also develop into a weed plague in their natural range. In southern Texas, farmers plowed large areas of farmland to cultivate exotic grasses. However, they also ensured the massive vegetative reproduction of Opuntia engelmannii .

Danger

Appendix I of the Washington Convention on Endangered Species does not contain any opuntia. In the Red List of Threatened Species of IUCN , however, ten species are listed with different threat status. Two species, Opuntia chaffeyi and Opuntia saxicola , are considered critically endangered. The endemic species Opuntia echios , Opuntia galapageia , Opuntia helleri and Opuntia insularis are classified as threatened or endangered in the Galápagos Islands . This degree of endangerment also applies to Opuntia megarhiza , Opuntia megasperma and Opuntia pachyrrhiza . The only non-endangered of the ten Opuntia species on the Red List is Opuntia monacantha .

proof

literature

- Edward F. Anderson : The Cactus Family . Timber Press, Portland (Oregon) 2001, ISBN 0-88192-498-9 .

- NL Britton , JN Rose : The Cactaceae. Descriptions and Illustrations of Plants of the Cactus Family . Volume I, Washington 1919, pp. 42-213.

- Curt Backeberg : Die Cactaceae: Handbuch der Kakteenkunde . Volume I, 2nd edition. 1982, ISBN 3-437-30380-5 , pp. 349-628.

- RA Donkin: Spanish Red: An Ethnogeographical Study of Cochineal and the Opuntia Cactus. In: Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, New Series. Volume 67, No. 5, 1977, pp. 1-84. (JSTOR)

- Candelario Mondragón-Jacobo, Salvador Pérez-González (eds.): Cactus (Opuntia spp.) As Forage. FAO Plant Production and Protection Paper 169 . Rome 2001, ISBN 92-5-104705-7 . (on-line)

- Donald J. Pinkava: Opuntia. In: Flora of North America Editorial Committee (Ed.): Flora of North America North of Mexico . Volume 4, New York / Oxford 2003, p. 123. (online)

- JA Reyes-Agüero, JR Aguirre, R. and A. Valiente-Banuet: Reproductive biology of Opuntia: A review. In: Journal of Arid Environments. Volume 64, No. 4, March 2006, pp. 549-585, doi: 10.1016 / j.jaridenv.2005.06.018

- Gordon Douglas Rowley : A History of Succulent Plants . Strawberry Press, 1997, ISBN 0-912647-16-0 .

- Florian C. Stintzing, Reinhold Carle: Cactus stems (Opuntia spp.): A review on their chemistry, technology, and uses. In: Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. Volume 49, No. 2, 2005, pp. 175-194. doi: 10.1002 / mnfr.200400071

Individual evidence

- ^ A. Michael Powell, James F. Weedin: Cacti of the Trans-Pecos & Adjacent Areas . Texas Tech University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-89672-531-6 , p. 40.

- ↑ Wolfgang Stuppy: Glossary of Seed and Fruit Morphological Terms - Kew Gardens. 2004, online ( memento of the original from October 17, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF).

- ^ NF McCarten: Fossil cacti and other succulents from the Late Pleistocene. In: Cactus and Succulent Journal. Volume 53, 1981, pp. 122-123.

- ^ BR Grant, PR Grant: Exploitation of Opuntia cactus by birds on the Galápagos. In: Oecologia. Volume 49, No. 2, Springer, Berlin / Heidelberg 1981, pp. 179-187. doi: 10.1007 / BF00349186

- ^ Philip Miller: The Gardeners Dictionary. Containing the Methods of Cultivating and Improving All Sorts of Trees, Plants, and Flowers, for the Kitchen, Fruit, and Pleasure Gardens; as Also Those which are Used in Medicine. … Abridged from the Last Folio Edition… 3 volumes, 1754. (online)

- ^ Beat Ernst Leuenberger : Interpretation and typification of Cactus ficus-indica Linnaeus and Opuntia ficus-indica (Linnaeus) Miller (Cactaceae). In: Taxon. Volume 40, No. 11, November 1991, pp. 621-627. (JSTOR)

- ^ A b Edward F. Anderson : The great cactus lexicon . Eugen Ulmer KG, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-8001-4573-1 , p. 446-482 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g Lucas C. Majure, Walter S. Judd, Pamela S. Soltis and Douglas E. Soltis. 2017. Taxonomic Revision of the Opuntia humifusa complex (Opuntieae: Cactaceae) of the eastern United States. Phytotaxa. 290 (1); 1-65. doi: 10.11646 / phytotaxa.290.1.1

- ↑ César Ramiro Martínez – González, Clemente Gallegos – Vazquez, Isolda Luna – Vega & Ricardo García – Sandoval: Opuntia leiascheinvariana , a new species of Cactaceae from the state of Hidalgo, Mexico. Botanical Sciences, vol.93 no.3 México sep. 2015 doi: 10.17129 / botsci.247

- ↑ C. Pérez, SJ Reyes, IC Brachet: Opuntia olmeca, una nueva especie de la familia Cactaceae para el estado de Oaxaca, México. In: Cactáceas y Succulentas Mexicanas. Volume 50, Number 3, 2005, pp. 89-95.

- ↑ Gottfried Große: Cajus Plinius Secundus. Natural history . 1783–1786, Volume 4, Book 21, Chapter 64, p. 198.

- ↑ Yudi Yuviama: Food Preparation in Aztec community . (accessed on September 5, 2008, not linkable due to spam protection filter)

- ↑ Steven Forster: America's First Herbal: The Badianus Manuscript . (accessed on September 5, 2008)

- ↑ Rowley 1997, p. 61 and p. 119.

- ↑ Rowley 1997, p. 61.

- ↑ German translation in: Monthly for Kakteenkunde . No. 11, 1919, p. 120.

- ^ Marco Antonio Anaya-Pérez: History of the use of Opuntia as forage in Mexico. In: Candelario Mondragón-Jacobo, Salvador Pérez-González (eds.): Cactus (Opuntia spp.) As Forage. FAO Plant Production and Protection Paper 169 . Rome 2001, ISBN 92-5-104705-7 . (on-line)

- ^ Joseph Pitton de Tournefort: Institutiones Rei Herbariae . 3 volumes, Paris 1700, volume 1, pp. 239–240 and volume 2, plate 122. (description , illustration)

- ^ Philip Miller: The Gardeners Dictionary. Containing the Methods of Cultivating and Improving All Sorts of Trees, Plants, and Flowers, for the Kitchen, Fruit, and Pleasure Gardens; as Also Those which are Used in Medicine. … Abridged from the Last Folio Edition… 3 volumes, 1754. (online)

- ↑ Philip Miller: The gardeners dictionary: containing the best and newest methods of cultivating and improving the kitchen, fruit, flower garden, and nursery, as also for performing the practical parts of agriculture, including the management of vineyards, with the methods of making and preserving wine, according to the present practice of the most skilful vignerons in the several wine countries in Europe, together with directions for propagating and improving, from real practice and experience, all sorts of timber trees. 8th edition. London 1768. (online)

- ^ Georg Engelmann: Synopsis of the Cactaceae of the Territory of the United States and Adjacent Regions. In: Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Volume 3, 1856, pp. 269-314.

- ^ Reunion of the genus Opuntia Mill. In: National Cactus and Succulent Journal. Volume 13, 1958, pp. 3-6.

- ^ R. Kiesling: Estudios en Cactaceae de Argentina: Maihueniopsis. Tephrocactus y generos afines (Opuntioideae). In: Darwiniana. Volume 25, 1984, pp. 171-215.

- ^ D. Hunt, N. Taylor (Eds.): Studies in the Opuntioideae (Cactaceae). Succulent Plant Research. Volume 6, Rainbow Gardens Bookshop, 2002, ISBN 0-9538134-1-X .

- ↑ Rowley 1997, p. 34.

- ^ Carlos Ostolaza: Etnobotánica. III. La Cultura Paracas. In: Quepo. Volume 10, 1996, pp. 42-49.

- ^ Edward F. Anderson: The Cactus Family . Timber Press, Portland (Oregon) 2001, p. 65.

- ↑ Anderson 2001, p. 64.

- ^ Preface. In: FAO Plant Production and Protection Paper 169.

- ↑ Peter Felker, Andrew Paterson, Maria M. Jenderek: Forage Potential of Opuntia Clones Maintained by the USDA, National Plant Germplasm System (NPGS) Collection. In: Crop Science. Volume 46, 2006, pp. 2161-2168. (on-line)

- ↑ Robert Ebermann, Ibrahim Elmadfa: Textbook food chemistry and nutrition. Springer, Vienna 2011, ISBN 978-3-7091-0210-7 , p. 469.

- ^ Herbert P. Goodheart, Arthur C. Huntley: Cactus Dermatitis. In: Dermatology Online Journal. Volume 7, No. 2, 2001. (online)

- ↑ H. Müller-Schärer: Biological processes. In: P. Zwerger, HU Ammon: Weeds: Biology and Control . Ulmer Verlag, Stuttgart 2002, p. 119. (PDF online)

- ^ Alan P. Dodd: The control and eradication of prickly pear in Australia. In: Bulletin of Entomological Research. Volume 27, 1936, pp. 503-517.

- ^ S. Raghu, Craig Walton: Understanding the Ghost of Cactoblastis Past: Historical Clarifications on a Poster Child of Classical Biological Control. In: BioScience. Volume 57, No. 8, pp. 699-705. doi: 10.1641 / B570810

- ↑ Anderson 2001, p. 67.

- ↑ M. Alma Solis, Stephen D. Hight, Doria R. Gordon: Tracking the Cactus Moth, Cactoblastis cactorum Berg., As it flies and eats its way westward in the US In: News of the Lepidopterists' Society. Volume 46, No. 1, pp. 3–4, 7. (PDF online)

- ^ Search for "Opuntia" in the IUCN 2007 Red List of Threatened Species . Accessed September 4, 2008.

New literature

- Lucas C. Majure, Raul Puente, M. Patrick Griffith, Walter S. Judd, Pamela S. Soltis, Douglas E. Soltis: Phylogeny of Opuntia ss (Cactaceae): Clade delineation, geographic origins, and reticulate evolution. In: American Journal of Botany. Volume 99, Number 5, 2012, pp. 847-864. doi: 10.3732 / ajb.1100375

- Lucas C. Majure, Walter S. Judd, Pamela S. Soltis, Douglas E. Soltis: Cytogeography of the Humifusa clade of Opuntia ss Mill. 1754 (Cactaceae, Opuntioideae, Opuntieae): correlations with pleistocene refugia and morphological traits in a polyploid complex . In: Journal of Comparative Cytogenetics. Volume 6, Number 1, 2012, pp. 53-77. doi: 10.3897 / CompCytogen.v6i1.2523

Web links

- Prickly pear infested areas of Australia , video from 1926 about the fight against opuntia in Australia

- www.opuntien.de