George Engelmann

George Engelmann (born February 2, 1809 in Frankfurt am Main , † February 4, 1884 in St. Louis ; actually Georg Theodor Engelmann ) was a German-American doctor and botanist who was mainly known for his first descriptions of North American cactus plants . Its official botanical author's abbreviation is “ Engelm. "

George Engelmann received his doctorate in 1831 with a thesis on flower malformations , which aroused Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's interest. At the request of his uncle Joseph Engelmann , he left Germany in 1832 to explore the possibilities of buying land in the United States . Three years later Engelmann opened a medical practice in St. Louis , through which he earned a living. During the first few years of his stay in the United States, he collected numerous plants which he sent to the Berlin Botanical Garden . It was through these collections that Asa Gray became aware of him. Together they encouraged private plant collectors, including Engelmann's former fellow student Ferdinand Lindheimer , to go on collecting tours in the barely developed territories northwest of St. Louis and together they described numerous new plant species .

Engelmann's first independent botanical publications dealt with the genus silk ( Cuscuta ). His main botanical interest has long been in the cactus family . In 1859 his extensively illustrated work Cactaceae of the Boundary was published, which gave an overview of all North American cactus species known up to that point. Later he dealt with vines , yuccas , agaves , bream herbs and wrote about the North American oaks , conifers and rushes .

Engelmann advised Henry Shaw (1800–1889) on the layout of his botanical garden, which later became the Missouri Botanical Garden . In 1856 he and like-minded people founded the Academy of Science of St. Louis , of which he was president for many years.

Live and act

Origin and education

George Engelmann was the first of 13 children of the pedagogue Julius Bernhard Engelmann (1773-1844) and Julie Antonie May (1789-1865), a daughter of the painter Georg Oswald May . His paternal grandfather was the Reformed theologian Theodore Erasmus Engelmann (1730–1802). George Engelmann's father founded an educational institute for girls in 1808, which taught according to Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi's educational methods. He was also one of the founders of the Senckenberg Natural History Museum and was a member of the Senckenberg Natural Research Society . George Engelmann's interest in botany was aroused at the age of 15 when he took part in the botanical excursions led by the botanist Johannes Becker (1769–1833) at the Senckenberg Institute .

A scholarship from the Reformed Church in Frankfurt enabled George Engelmann to study theology in Heidelberg in 1827 , which he quickly gave up in favor of studying medicine. His fellow students included Louis Agassiz , Karl Friedrich Schimper and Alexander Braun . After the storming of the Heidelberger Karzers by fraternity members on 14 August 1828 and the subsequent exodus of Heidelberg students to Frankenthal George Engelmann went in the fall of 1828 to Berlin , where he attended the Friedrich-Wilhelm University continued his studies. Two years later he moved to the University of Würzburg , where Johann Lukas Schönlein taught. There, on July 9, 1831, George Engelmann defended his dissertation De Antholysi Prodromus (German: About the flower solution ), a botanical text on the teratology of flowers , and was awarded a doctorate in medicine with this . At the request of his father, Marianne von Willemer sent a copy of George Engelmann's dissertation to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in February 1832 . Shortly before his death, Goethe, who had dealt intensively with the metamorphoses of plants , expressed great interest and wanted to learn more about the author's living conditions.

In 1832 George Engelmann followed his college friends Louis Agassiz and Alexander Braun to Paris to deepen his knowledge. Since cholera was rampant in Paris at that time , however, he stayed mainly in the Paris hospitals. On February 10, 1832, George Engelmann became a member of the Regensburg Botanical Society and on August 29, 1832 a full member of the Senckenberg Natural Research Society .

Emigrated to the United States

In April 1832, shortly before George Engelmann left for Paris, a meeting of the Engelmann families took place at his uncle Joseph Engelmann's house in Wachenheim , at which they discussed emigration to the United States without, however, reaching a concrete result. Joseph Engelmann finally made a proposal to George Engelmann that he should explore the possibilities of buying land in the United States at his own expense. George Engelmann embarked in Bremen in September 1832 and arrived in Baltimore in December 1832 .

After a short stay in Philadelphia , where he met the botanist Thomas Nuttall , he probably traveled by steamboat first down the Ohio River and then up the Mississippi River to St. Louis , Missouri . For the next six months he lived ten miles west of St. Louis with a friend of his uncle Joseph's, studying the geology and flora of the area. In the summer of 1833, forester Friedrich Theodor Engelmann (1779–1854), another uncle, arrived with his wife and their nine children. George Engelmann loaned this $ 600 from his uncle Joseph, with whom Friedrich Theodor Engelmann bought a farm twenty miles east of St. Louis in the Shiloh Valley near Belleville . George Engelmann moved to the farm and lived there with his cousin Theodor Engelmann and Gustav Körner , among others . Every day he recorded the air temperature , prepared snake skins, stuffed birds and passed the time hunting. He also collected plants that he dried. At the end of the summer of 1833, George Engelmann sent a collection of seeds to Georg Fresenius , head of the herbarium at the Senckenberg Institute in Frankfurt am Main. He discussed art, politics and natural history extensively with his roommates. One of their discussion topics was Gottfried Duden's 1829 report on the western states of North America, which had induced many Germans to emigrate, but which contained numerous misrepresentations, for example about the allegedly mild climate.

As a doctor, George Engelmann rarely had to work. Only 12 to 15 of the 70 to 80 German emigrants fell ill within the first two years of their stay. At the end of 1834 or beginning of 1835 he moved to St. Louis with his cousin Theodor, where they lived in a small house on the corner of Second and Chestnut Streets. At that time, there were around 8300 residents in the rapidly growing St. Louis. The resolve to practice medicine did not last long. George Engelmann considered expanding his explorations to include the central Mississippi Valley. In the spring of 1835 he left for Arkansas and the Indian Territory . He spurned the well-known route to Little Rock and got as far as Fort Gibson . One of the places he went to along the way was the Hot Springs hot springs . In the autumn of 1835 he lost his collection while crossing the rivers that were swollen by the rain and probably fell ill with malaria . With the help of an African American family who took care of him for a time, he was strong enough to return to St. Louis, where his cousin Theodor nursed him to health.

Established as a doctor in St. Louis

In January 1836, George Engelmann began to work seriously as a doctor. He placed an advertisement in the St. Louis Anzeiger des Westens , a German weekly newspaper, for six months that eventually brought him enough patients to earn a living from his work as a doctor. In May 1836 he was inducted into the Medical Society of Missouri by his colleagues .

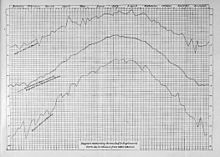

As far as his work as a practicing doctor allowed, George Engelmann continued to devote himself to his studies of nature. He watched the course and the water level of the Mississippi. He expanded his meteorological observations to include the measurement of air pressure , amount of precipitation and humidity . He noted the degree of cloudiness and the wind conditions . From February 1836, George Engelmann published his weekly temperature measurements in the St. Louis Anzeiger des Westens . In the course of 1836 he began to exchange views on natural history topics with like-minded people. The St. Louis Association of Natural Sciences , as they called their small community, became the Western Academy of Natural Sciences in February 1837 . Engelmann was responsible for chemistry and mineralogy. In the spring of 1837 he traveled a second time to Arkansas for a few weeks to investigate silver ore on behalf of a silver mining company , which, however, turned out to be insufficiently rich in content. This was George Engelmann's last excursion for a long time.

Together with the Polish captain Carl Neyfeld, George Engelmann published the magazine Das Westland in 1837 , which was created in response to Duden's travel report from 1829 and was printed by his uncle Joseph Engelmann in Heidelberg. In the only three-issue journal, George Engelmann wrote about the German community near Belleville, the climate and geology of this area and his journey to the southern areas of Missouri and Arkansas.

In order to be able to travel to Germany, George Engelmann left the responsibility for his practice to Friedrich Adolph Wislizenus in autumn 1839 . On June 11, 1840, he married his cousin and long-time fiancée Dorothea Horstmann (1804–1879) in Kreuznach . Their only child was the doctor Georg Julius Engelmann . After his return, George Engelmann and Friedrich Adolph Wislizenus ran the practice together until 1846.

Botanist at the "gateway to the west"

During his trip to Europe, Asa Gray discovered numerous specimens of North American plants from George Engelmann in the herbarium of the Botanical Garden in Berlin , which was directed by Johann Friedrich Klotzsch . Asa Gray and John Torrey , who worked with him, first met George Engelmann on his return trip from Germany in New York . An intensive cooperation developed between them in the processing of the North American flora.

In 1842 George Engelmann published his first botanical work on the North American flora in the American Journal of Science and Arts . In it he dealt with the genus silk ( Cuscuta ). In the United States only the occurrence of the species Cuscuta americana was known until then . George Engelmann had found some species of the genus that he first described in his article in the vicinity of St. Louis . In addition, based on his investigations, he separated the genus Lepidanche , which is no longer recognized today. The article was followed by minor additions and corrections that appeared in various magazines in the following year.

For Asa Gray, who worked together with John Torrey on a flora of North America, George Engelmann at the “Gateway to the West” was the ideal partner to get new plant material. Engelmann should look out for possible plant collectors and instruct them. Engelmann was aware that potential plant collectors had to make a living from their work and he suggested to Gray to offer the collected plants for sale. Gray agreed and announced in Benjamin Silliman's magazine that Karl Andreas Geyer and Friedrich Lüders were in the Rocky Mountains and Ferdinand Lindheimer wanted to explore the flora of Texas for a few years . Subscriptions could purchase the plants they collected at a cost of eight and ten dollars per hundred, respectively. In order to convince potential buyers of the quality of the plants, George Engelmann prepared a catalog of the plants that Karl Andreas Geyer had previously collected in Illinois and Missouri . Karl Andreas Geyer's and Friedrich Lüder's collecting activities were - due to various circumstances - not very successful. The plants collected by Ferdinand Lindheimer in Texas are described by George Engelmann and Asa Gray in 1845 and 1850 in two lengthy treatises entitled Plantae Lindheimerianae .

Another successful plant collector that George Engelmann hired in St. Louis was August Fendler . August Fendler, at the suggestion of Asa Gray, collected for a few months in the vicinity of Santa Fe in New Mexico during the Mexican-American War and returned with a wealth of material, which was described in Plantae Fendlerianae in 1848 .

Between 1835 and 1847 George Engelmann sent 7,900 plants to Berlin, 2,900 to Saint Petersburg and 900 to Asa Gray, according to his own records .

Specialist in North American cacti

George Engelmann's business partner Friedrich Adolph Wislizenus prepared shortly before the outbreak of the Mexican-American War for a scientific expedition that was to take him to Northern Mexico and Upper California . Wislizenus reached Chihuahua via Santa Fe , accompanied by a trader . There he was detained in the city of Cusihuiriachi for almost six months as a result of the chaos of war . Wislizenus completed the way back to St. Louis as a doctor in Colonel Alexander William Doniphan's column . After Wislizenus' return in early July 1847, Engelmann took over the processing of the botanical collection for his travel report. This work first turned George Engelmann's attention to the cactus family . He described the cactus genus Echinocereus with ten species and another ten species from the genera Cereus , Echinocactus , Mammillaria and Opuntia . Engelmann also worked on the cacti for Colonel William Hemsley Emorys (1811-1887) records of a reconnaissance mission that led from Fort Leavenworth to San Diego and the Gila River in 1846/1847 . According to drawings by JM Stanly, he described three species of the genus Mammillaria and four of the genus Opuntia . The most important new discovery on this mission was a giant columnar cactus, for which Engelmann suggested the name Cereus giganteus . Engelmann prepared a provisional description for the species, which was followed by revised versions in 1852 and 1854. Today, Cereus giganteus is the only species in the genus Carnegiea .

After the Mexican-American War, the character of the exploration of the American-Mexican border area changed. The private plant collectors gave way to state-funded research expeditions that began to systematically explore the unknown territory. The plant collectors working for the Boundary Commission , including Charles Christopher Parry , George Thurber (1821–1890), Charles Wright , John Milton Bigelow and Arthur Schott (1814–1875), sent the cacti they found directly to Engelmann. Amiel Weeks Whipple (1816–1863) explored the possibilities for a transcontinental rail connection along the 35th parallel from 1853 to 1854, Joseph Christmas Ives (1828–1868) from 1857 to 1858 the Colorado River and James Hervey Simpson (1813–1883) that Great Basin in Utah . Engelmann also described the cacti for the reports on these expeditions.

Since the printing of the official reports of the Boundary Commission and the Pacific Railroad Surveys still took some time, Engelmann wanted to summarize the previous knowledge about the cactus flora of North America and make it known to the public. He prepared brief descriptions of the species and presented them together with the already known species, which, among other things, went back to the collecting activities of Heinrich Poselger (1818-1883) and Auguste Adolphe Lucien Trécul (1818-1896) in South Texas and North Mexico, in systematic form. He published the result in 1856 under the title Synopsis of the Cactaceae of the Territory of the United States and Adjacent Regions (about the outline of the cacti in the United States and neighboring areas ). In his “demolition” Engelmann divided the habitats of North American cacti into eight different areas based on their geographical distribution .

In 1859 the three-volume report of the Boundary Commission appeared , which documented the eight-year survey work in the US-Mexican border area led by William Hemsley Emory. The report contained Engelmann's most important individual work with Cactaceae of the Boundary (about cacti on the borderline ). Engelmann had already completed the text in 1856. The report was illustrated with 75 full-page drawings that Paulus Roetter had made.

In November 1856, George Engelmann left St. Louis and went with his family to the east coast, where he worked for some time in Asa Gray's herbarium. A 15-month stay in Europe followed. Engelmann wanted to make known in Europe the Academy of Science of St. Louis , founded on March 10, 1856 , of which he was the first president. He also wanted to take care of the completion of the lithographs for his monograph Cactaceae of the Boundary . His travels in Europe took him to London, Paris, Geneva, Naples, Rome, Vienna, Leipzig, Frankfurt and Berlin. In Germany he was the guest of the cactus lover Joseph zu Salm-Reifferscheidt-Dyck and met Alexander von Humboldt in Berlin in 1857 . In London he stayed with William Jackson Hooker in his Royal Botanic Garden . After his return he briefed the members of the Academy of Science of St. Louis in early September 1858 about his stay in Europe.

Shaw's Botanical Garden

In a letter from the beginning of April 1856 Engelmann mentioned the Englishman Henry Shaw (1800-1889) for the first time to Asa Gray . Shaw had settled in St. Louis in 1819 and made a fortune trading hardware and importing and exporting that allowed him to retire in 1840. Shaw bought large pieces of land west of St. Louis and hired an architect to build a manor house on it. The building called Tower Grove House was completed in 1849 when Shaw was in Europe, visiting the Royal Botanic Garden in Kew and Chatsworth House . The two botanical grounds impressed Shaw so much that in 1855 he decided to design part of his property as a botanical garden . Shaw asked William Jackson Hooker for advice, but he referred him to George Engelmann. Engelmann convinced Shaw to create space for a herbarium and a botanical library in his botanical garden . Shaw commissioned Engelmann in 1857, when he was touring Europe, to buy books and herbaria for the future botanical museum. At the end of December 1857, Engelmann negotiated with the heirs of Johann Jakob Bernhardi in Leipzig about the purchase of his herbarium. Engelmann acquired the Bernhardis Herbarium, which comprises over 62,000 specimens and represents over 40,000 species, for $ 600. In 1859 the Botanical Museum was completed and Shaw's Garden , the forerunner of the Missouri Botanical Garden , opened to the public.

Further work

After his return from Europe in 1858, Engelmann withdrew more and more from the daily routine of his medical practice in order to be able to pursue his botanical research. His main botanical works, written after 1860, dealt with the vines ( Vitis ), the yuccas and agaves , the bream herbs ( Isoetes ), the milkweed family (Euphorbiaceae) and the silk plant family (Asclepiadaceae). He wrote treatises on oaks ( Quercus ) and conifers and wrote a revision of the North American rushes ( Juncus ).

After 1856 Engelmann served again from 1861 to 1867, 1870 and from 1878 to 1884 as President of the Academy of Science of St. Louis . In 1868 Engelmann returned to Germany, where he spent a year while his son studied at the University of Berlin.

From 1870 Engelmann undertook several botanical exploration tours. Two of them took him to the mountainous region of Colorado and New Mexico , another to the Lake Superior area and another to the Indian territory . On an extended tour, he toured the Appalachians of Tennessee and North Carolina and later the Utah Territory . After the death of his wife in 1879, Engelmann accepted an invitation from Charles Sprague Sargent in the summer of 1880 to explore the rainforests of the Pacific Northwest . The excursion took him through the Rocky Mountains to British Columbia . On the way back they crossed the Sonoran Desert in Arizona .

In 1883 Engelmann traveled with his son and daughter-in-law to Germany for a recreational stay, during which he visited his sisters in Kreuznach . He died soon after his return on February 4, 1884 at 5:30 p.m. of complications from a heart condition. He was buried in Bellefontaine Cemetery. Shortly before his death, Engelmann published in his last scientific paper the data he had collected from 1836 to 1882 on the daytime temperatures in St. Louis.

Reception and aftermath

Awards and recognition

George Engelmann was a member, corresponding member or honorary member of numerous scientific academies and learned societies . In the United States, these included the American Association of Geologists and Naturalists (April 2, 1840), the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia (October 27, 1840), the Lyceum of Natural History New York (August 3, 1846), the American Association for the Advancement of Science (September 20, 1847); and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1847). In Germany he was a member or honorary member of the Geographisches Verein zu Frankfurt am Main (March 21, 1840), the Rheinische Naturforschenden Gesellschaft in Mainz (October 18, 1838), the Pollichia (October 6, 1843), the Society for the Advancement of Natural Sciences Freiburg (February 26, 1847), the Natural Science Association in Hamburg (March 1, 1852), the Society for Geography in Berlin (April 4, 1857), the German Academy of Natural Scientists Leopoldina (1864), the Botanical Association for the Province of Brandenburg and the neighboring countries (October 1879) and the Society of German Natural Scientists and Doctors . He was admitted to the Linnean Society of London on May 2, 1878.

The University of Missouri awarded Engelmann an honorary doctorate in law on June 24, 1875. The University of Würzburg appointed him an honorary doctorate in philosophy on July 9, 1881, on the occasion of his 50th anniversary as a doctor.

The Academy of Science of St. Louis dedicated its session on February 1, 1909, to the 100th birthday of its co-founder and first president. The doctor Gustav Baumgarten (1837–1910), who was friends with Engelmann, opened the evening with a lecture on Engelmann's character. This was followed by Herbert Allen Wheelers (1859–1950) lecture on his contributions to geognosy . Subsequently, Francis Eugene Nipher (1847–1926) from Washington University paid tribute to Engelmann's work in the field of meteorology . William Trelease from the Missouri Botanical Garden closed the evening with his lecture on Engelmann's contributions to biology.

On the occasion of Engelmann's 100th anniversary of his death, the Missouri Botanical Garden dedicated the 31st annual symposium on systematics, held on October 19-20, 1984, to his memory. In the summer of 2011, the Missouri Botanical Garden announced that George Engelmann's legacy would be digitally processed and made available to the public.

John Torrey and Asa Gray named the plant genus Engelmannia Torr in honor of George Engelmann . & A.Gray in the daisy family . Furthermore, several plant species are named after him, for example the Engelmann spruce ( Picea engelmannii ), Agave engelmannii , Echinocereus engelmannii and Opuntia engelmannii . Charles Christopher Parry named Engelmann Peak, 4073 meters high, in Clear Creek County , after Engelmann .

In 2000, a bronze bust created by the artist Paul T. Granlund (1925-2003) was placed in front of the Missouri Botanical Garden in St. Louis.

Estate and correspondence

According to his own records, Engelmann corresponded with 99 correspondents abroad and 70 in the United States. His foreign correspondence partners included Frédéric Albert Constantin Weber in France, Elias Magnus Fries in Sweden, Eduard August von Regel in Russia, Alexander von Humboldt in Germany and Alphonse Pyrame de Candolle in Switzerland.

Engelmann's herbarium, comprising over 97,000 specimens, was given to the Missouri Botanical Garden by his son Georg Julius Engelmann in 1892. The US Weather Bureau received his meteorological records from 1836 to 1882 . They are still proving useful in long-term studies of the weather today.

The George Engelmann Papers kept at the Missouri Botanical Garden consist of about 5000 letters and 30 boxes of botanical notes. Additional archival material is in the Gray Herbarium and the Missouri Historical Society.

Fonts (selection)

Botanical

- De Antholysi Prodromus. Dissertatio inauguralis phytomorphologica . Frankfurt am Main 1832, (online) .

- A Monography of North American Cuscutineae. In: American Journal of Science and Arts. Volume 43, 1842, pp. 333-345, (online) .

- Catalog of a collection of Plants made in Illinois and Missouri. by Charles A. Geyer; with critical remarks, & c. In: American Journal of Science and Arts. Volume 46, 1844, pp. 94-104, (online) .

- Plantae Lindheimerianae: An Enumeration of the Plans collected in Texas, and distributed to Subscribers, by F. Lindheimer, with Remarks, and Descriptions of new Species, & c. In: Boston Journal of Natural History . Volume 5, 1845, pp. 210-264, (online) . - with Asa Gray

- Botanical Appendix. In: Friedrich Adolph Wislizenus: Memoir of a Tour to Northern Mexico: Connected with Col. Doniphan's Expedition, in 1846 and 1847 . Tippin & Streeper, Washington 1848, pp. 87-115, (online) .

- [ Cactaceae ]. In: William Hemsley Emory: Notes of a Military Recomnoissance from Fort Leavenworth, in Missouri, to San Diego in California . Wendell & Benthuysen, Washington 1848, pp. 155-159, (online) .

- Systematic arrangement of the species of the genus Cuscuta, with critical remarks on old species and descriptions of new ones. In: Transactions of the Academy of Science of St. Louis . Volume 1, 1859, pp. 453-523, (online) .

- Notes on the Cereus giganteus of South Eastern California and some other Californian Cactaceae. In: American Journal of Science and Arts. Second Series, Volume 14, 1852, pp. 335-339, p. 446, (online) .

- Further Notes on Cereus giganteus of Southeastern California, with a short account of another allied species of Sonora. In: American Journal of Science and Arts. 2nd episode, Volume 17, 1854, pp. 231-235, (online) .

- Description Of The Cactaceae. In: Route near the thirty-fifth parallel explored by Lieutenant AW Whipple, Topographical Engineers, in 1853 and 1854 . Volume 4, Part 5, Report Of The Botany Of The Expedition, B. Tucker, Washington 1856, pp. 27-58, (online) . - with John Milton Bigelow

- Cactaceae of the Boundary. In: United States and Mexican Boundary Survey, under the Order of Lietu. Col. WH Emory, Major First Cavalry, and United States Commissioner . Volume 2, Part 1, Cornelius Wendell, Washington 1859, (online) .

- Cactaceae. In: Report upon the Colorado River of the West, explored in 1857 and 1858 by Lieutenant Joseph C. Ives, Corps of Topographical Engineers under the direction of the Office of explorations and surveys, AA Humphreys, Captain Topographical Engineers, in charge; By order of the Secretary of War . United States Government Printing Office , Washington 1861, Botany, pp. 12-14, (online) .

- Euphorbiaceae. In: Report upon the Colorado River of the West, explored in 1857 and 1858 by Lieutenant Joseph C. Ives, Corps of Topographical Engineers under the direction of the Office of explorations and surveys, AA Humphreys, Captain Topographical Engineers, in charge; By order of the Secretary of War . Government Printing Office, Washington 1861, Botany, pp. 26-27, (online) .

- A Revision of the North American Species of the Genus Juncus, with a description of new or imperfectly known species. In: Transactions of the Academy of Science of St. Louis . Volume 2, 1868, pp. 424-498, p. 590, (online) .

- Notes on the Genus Yucca. In: Transactions of the Academy of Science of St. Louis . Volume 3. 1873, pp. 17-64, (online) .

- Notes on agave. In: Transactions of the Academy of Science of St. Louis . Volume 3, 1878, pp. 291-322, (online) .

- About the Oaks of the United States. In: Transactions of the Academy of Science of St. Louis . Volume 3, 1876/1877, pp. 372-400, pp. 539-543, (online) .

- The genus Isoetes in North America. In: Transactions of the Academy of Science of St. Louis . Volume 4, 1882, pp. 358-390, (online) .

- The true Grape Vines of the United States. In: Bush & Son & Meissner: Illustrated Descriptive Catalog of American Grape Vines. A Grape Growers' Manual . 3. Edition. RP Studley & Co., St. Louis 1883, pp. 9-20, (online) .

- The Diseases of Grape Vines. In: Bush & Son & Meissner: Illustrated Descriptive Catalog of American Grape Vines. A Grape Growers' Manual . 3. Edition. RP Studley & Co., St. Louis 1883, pp. 47-48, (online) .

- William Trelease, Asa Gray (Ed.): The botanical works of the late George Engelmann, collected for Henry Shaw, esq. J. Wilson and Son, Cambridge (MA) 1887, (online) . - Posthumously

Meteorological

- Fall of Rain in St. Louis During Twenty Three Years - 1839 to 1861. In: Transactions of the Academy of Science of St. Louis . Volume 2, number 1, 1861, p. 75, (online) .

- Fall of Snow (melted) in St. Louis in 23 Years, from 1839 to 1861. In: Transactions of the Academy of Science of St. Louis . Volume 2, number 1, 1861, p. 76, (online) .

- Fall of Rain (including melted snow) in St. Louis, from 1839 to 1861. In: Transactions of the Academy of Science of St. Louis . Volume 2, Number 1, 1861, pp. 77-79, (online) .

- Altitude of Pike's Peak and other points in Colorado Territory. In: Transactions of the Academy of Science of St. Louis . Volume 2, Number 1, pp. 126-133, (online) .

- The mean and extreme daily Temperatures in St. Louis during forty seven years, as calculated from daily observations. In: Transactions of the Academy of Science of St. Louis . Volume 4, 1883, pp. 496-508, (online) .

Others

- The Westland. North American magazine for Germany . Heidelberg 1837. - as author and co-editor

literature

To the reception

- Edgar S. Anderson: Godfather of the Garden. In: Washington University Magazine . Volume 39, 1969, pp. 38-43.

- Richard G. Beidelman: George Engelmann, Botanical Gatekeeper of the West. In: Horticulture . Volume 48, Number 4, 1970, pp. 42-43, 52-53, 56-58.

- William G. Bek: George Engelmann, Man of Science . 1929.

- Part I. In: Missouri Historical Review. Volume 23, Number 2, January 1929, pp. 167-206, (online) .

- Part II. In: Missouri Historical Review. Volume 23, Number 3, April 1929, pp. 427-446, (online) .

- Part III. In: Missouri Historical Review. Volume 23, Number 4, July 1929, pp. 517-535, (online) .

- Part IV. In: Missouri Historical Review. Volume 24, Number 1, October 1929, pp. 66-86, (online) .

- Howard Elkinton: George Engelmann - Greatly Interested in Plants. In: The American-German Review . Volume 12, August 1946, pp. 16-21.

- Jerome Jansma, Harriet H. Jansma: George Engelmann in Arkansas Territory. In: The Arkansas Historical Quarterly . Volume 50, Number 3, 1991, pp. 225-248, JSTOR 40038186 .

- Jerome Jansma, Harriet H. Jansma: Engelmann Revisits Arkansas, the New State. In: The Arkansas Historical Quarterly . Volume 51, Number 4, 1992, pp. 328-356, JSTOR 40024100 .

- Barbara Lawton: George Engelmann, 1809-1884. Scientific father of the garden. In: Missouri Botanical Garden Bulletin . Volume 56, Number 6, St. Louis 1968, pp. 10-17, (online) .

- Michael Long: George Engelmann and the Lure of Frontier Science. In: Missouri Historical Review . Volume 89, Number 3, 1995 pp. 251-268, (online) .

- Maxwell Tylden Masters : The Late Dr. Engelmann. In: Nature . Volume 29, number 756, April 24, 1884, p. 599, doi: 10.1038 / 029599a0 .

- Larry W. Mitich: The Odyssey of Dr. George Engelmann. In: Excelsa , number 4, 1974. pp. 31-39.

- Paula Rebert: George Engelmann of St. Louis and his Contributions to Western Geography. In: Terrae Incognitae , Volume 32, Number 1, 2000, pp. 55-66.

- Charles Sprague Sargent: Botanical Papers of George Engelmann. In: Botanical Gazette . Volume 9, Number 5, 1884, pp. 69-74, JSTOR 2995110 .

- Elizabeth A. Shaw: Changing Botany in North America: 1835-1860 The Role of George Engelmann. In: Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden . Volume 73, Number 3, 1986, pp. 508-519, JSTOR 2399190 .

- Oscar H. Soule: Dr. George Engelmann: The First Man of Cacti and a Complete Scientist. In: Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden . Volume 57, Number 2, 1970, pp. 135-144, JSTOR 2395105 .

- Patricia P. Timberlake: George Engelmann, 1809-1884: Early Missouri Botanist. In: Missouri Folklore Society Journal , Volume 10, 1988 (Special Issue, Traditional Uses of Native Plants in Missouri), pp. 1-8.

- Steven J. Wolf: George Engelmann Type Specimens in the Herbarium of the Missouri Botanical Garden. In: Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden . Volume 75, Number 4, 1988, pp. 1608-1636, JSTOR 2399304 .

Biographical abstracts

- [Anonymous]: Sketch of George Engelmann, MD In: Popular Science Monthly . Volume 29, June 1886, pp. 260-265, (online) .

- Lawrence O. Christensen, Gary R. Kremer, William E. Foley, Kenneth H. Winn (Eds.): Dictionary of Missouri Biography. University of Missouri Press, 1999, ISBN 0-8262-1222-0 , pp. 284-286.

- Helmut Dolezal: Engelmann, Georg. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 4, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1959, ISBN 3-428-00185-0 , p. 518 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Asa Gray: George Engelmann. In: Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences . Volume 19, Boston 1884, pp. 516-522, (online) .

- ML Gray, FE Nipher: [ February 18, 1884 ]. In: The Transactions of the Academy of Science of St. Louis . Volume 4, 1886, pp. XC-XCV, (on-line) .

- Gustav Körner : The German element in the United States of North America, 1818–1848 . AE Milde & Co., Cincinnati 1880, pp. 327-331, (online) .

- Heinrich Armin Rattermann: Dr. med. Georg Engelmann. In: The German Pioneer . Volume 16, 1884-1885, pp. 260-267 , pp. 311-318 , pp. 361-371 .

- Enno Sander: George Engelmann. In: The Transactions of the Academy of Science of St. Louis . Volume 4, 1886, pp. 1-18, (online) .

- [Charles Sprague Sargent]: George Engelmann. In: Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club . Volume 11, Number 4, 1884, pp. 38-41, JSTOR 2476345 .

- [Charles Sprague Sargent]: Georg Engelmann. In: Science . Volume 3, number 61, April 4, 1884, pp. 405-408, doi: 10.1126 / science.ns-3.61.405 .

- Karl Schumann : life descriptions of famous cactus connoisseurs. Georg Engelmann. In: Monthly for cactus science . Volume 9, Number 10, 1899, pp. 145-148, (online) .

- Ignaz Urban : George Engelmann. In: Reports of the German Botanical Society . Volume 2, 1884, pp. XII-XV.

- Charles Abiathar White: Memoir of George Engelmann, 1809-1884. In: Biographical Memoirs of the National Academy of Science . Volume IV, Washington 1902, pp. 1-21, (pdf; 1.0 MB) .

- Ernst Wunschmann: Engelmann, Georg . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 48, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1904, pp. 376-378.

Letters

- [Anonymous]: Formative Days of Mr. Shaw's Garden. In: Missouri Botanical Garden Bulletin . Volume 30, Number 5, 1942, pp. 100-110, (online) .

- Minetta Altgelt Goyne: Letters to George Engelmann. Texas A&M University Press, Tamu (Texas) 1991, ISBN 0-89096-457-2 (hardcover) and ISBN 1-58544-021-3 (paperback).

- John Thomas Lee: Josiah Gregg and Dr. George Engelmann. In: Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society . Volume 41, Number 4, 1931, pp. 355-404.

- Michael T. Stieber, Carla Lange: Augustus Fendler (1813–1883), Professional Plant Collector: Selected Correspondence with George Engelmann. In: Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden . Volume 73, Number 3, 1986, pp. 520-531, JSTOR 2399191 .

Others

- G. Bäcker and F. Engelmann: The Electoral Palatinate families Engelmann and Hilgard. 1958 with a 1983 amendment, St. Clair County Historical Society, Belleville, Illinois.

- Ada M. Klett: Belleville Germans Look At America (1833-1845). In: Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society . Volume 40, Number 1, March 1947, pp. 23-37, JSTOR .

- Joseph Raimar: The Engelmann family from the Electoral Palatinate. In: Palatinate Genealogy . 1952, pp. 17-28.

- Cornelia Marshal Smith: Meusebach-Engelmann-Lindheimer. In: Texas Journal of Science . Issue 34, 1982.

Web links

- Author entry and list of the described plant names for George Engelmann at the IPNI

- Digitizing Engelmann's Legacy

- The George Engelmann Papers at the Biodiversity Heritage Library

- George Yatskievych: Missouri's First Botanists .

- Bob Graham: Wind River Range. Identification of the peak Frémont climbed in 1842 .

- Gravestone in Bellefontaine Cemetery

Individual evidence

- ↑ Thomas Joseph McCormack (Ed.): Memoirs of Gustave Koerner, 1809-1896. Life sketches written at the suggestion of his children . The Torch Press, Cedar Rapids (Ia) 1909, Volume 1, p. 43, (online) .

- ↑ a b c Heinrich Armin Rattermann: Dr. med. Georg Engelmann. In: The German Pioneer. Volume 16, 1884-1885, pp. 261-263.

- ^ Philipp Stein (ed.): Goethe's correspondence with Marianne von Willemer . Insel-Verlag, Leipzig 1908, p. 260.

- ^ Philipp Stein (ed.): Goethe's correspondence with Marianne von Willemer . Insel-Verlag, Leipzig 1908, p. 262.

- ↑ a b c Heinrich Armin Rattermann: Dr. med. Georg Engelmann. In: The German Pioneer. Volume 16, 1884-1885, pp. 370-371.

- ^ Asa Gray: George Engelmann. In: Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences . Volume 19, Boston 1884, p. 517.

- ^ [Charles Sprague Sargent]: Georg Engelmann. In: Science . Volume 3, Number 61, April 4, 1884, p. 405.

- ↑ a b Michael Long: George Engelmann and the Lure of Frontier Science. In: Missouri Historical Review . Volume 89, Number 3, 1995 pp. 255-264.

- ^ George Engelmann: The German branch in Illinois; five miles east of Belleville (with a charter). In: The Westland. North American magazine for Germany . Volume 1, number 3, Heidelberg 1837, p. 286.

- ↑ Logan Uriah Reavis: Saint Louis, the world city of the future . St. Louis 1870, p. 56, (online) .

- ^ A b c Michael Long: George Engelmann and the Lure of Frontier Science. In: Missouri Historical Review . Volume 89, Number 3, 1995 pp. 264-266.

- ^ Meteorological Tables for the year 1836, prepared by the Meteorological Department of the St. Louis Association of Natural Sciences. In: American Journal of Science and Arts . Volume 32, 1837, p. 386, (online) .

- ^ Asa Gray: Notices of European herbaria, particularly those most interesting to the North American botanist. In: The American journal of science . Volume 40, 1841, p. 17, (online) .

- ^ Elizabeth A. Shaw: Changing Botany in North America: 1835-1860 The Role of George Engelmann. In: Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden . Volume 73, Number 3, 1986, p. 514.

- ^ A b Elizabeth A. Shaw: Changing Botany in North America: 1835-1860 The Role of George Engelmann. In: Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden . Volume 73, Number 3, 1986, p. 515.

- ^ Asa Gray: Notice of Botanical Collections. In: American Journal of Science and Arts . Volume 45, Number 1, July 1843, pp. 225-227, (online) .

- ^ Elizabeth A. Shaw: Changing Botany in North America: 1835-1860 The Role of George Engelmann. In: Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden . Volume 73, Number 3, 1986, p. 516.

- ^ A b Rolla M. Tryon: A newly discovered cache of Engelmannia. In: Missouri Botanical Garden Bulletin . Volume 40, number 2, p. 46, (online) .

- ↑ Oscar H. Soule: Dr. George Engelmann: The First Man of Cacti and a Complete Scientist. In: Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden . Volume 57, Number 2, 1970, pp. 138-139.

- ^ Paula Rebert: George Engelmann of St. Louis and his Contributions to Western Geography. In: Terrae Incognitae , Volume 32, Number 1, 2000, p. 58.

- ^ Paula Rebert: George Engelmann of St. Louis and his Contributions to Western Geography. In: Terrae Incognitae , Volume 32, Number 1, 2000, pp. 57-58.

- ^ Paula Rebert: George Engelmann of St. Louis and his Contributions to Western Geography. In: Terrae Incognitae , Volume 32, Number 1, 2000, pp. 64-65.

- ^ A b Paula Rebert: George Engelmann of St. Louis and his Contributions to Western Geography. In: Terrae Incognitae , Volume 32, Number 1, 2000, p. 59.

- ^ A b Elizabeth A. Shaw: Changing Botany in North America: 1835-1860 The Role of George Engelmann. In: Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden . Volume 73, Number 3, 1986, p. 518.

- ^ Walter B. Hendrickson: St. Louis Academy of Science: The Early Years. In: Missouri Historical Review . Volume 61, Number 1, October 1966, p. 85, (online) .

- ^ Transactions of the Academy of Science of St. Louis . Volume 1, September 6, 1858, p. 316, (online) .

- ↑ Eric Sandweiss: St. Louis in the century of Henry Shaw: a view beyond the garden wall . University of Missouri Press, 2003, ISBN 0-8262-1439-8 , pp. 161.

- ^ [Anonymous]: Formative Days of Mr. Shaw's Garden. In: Missouri Botanical Garden Bulletin . Volume 30, Number 5, 1942, p. 101.

- ^ William G. D'Arcy: Mysteries and Treasures in Bernhardt Herbarium. In: Missouri Botanical Garden Bulletin . Vol. 59, 1971, pp. 20-25 (online) .

- ↑ Patricia P. Timberlake: George Engelmann, 1809-1884: Early Missouri Botanist. In: Missouri Folklore Society Journal , Volume 10, 1988 (Special Issue, Traditional Uses of Native Plants in Missouri), p. 3.

- ↑ Richard G. Beidelman: George Engelmann, Botanical gatekeeper of the West. In: Horticulture . Volume 48, Number 4, 1970, p. 57.

- ^ Frederick Starr: The Academy of Science of St. Louis. In: Popular Science . March 1898, p. 647, (online) .

- ↑ Howard Elkinton: George Engelmann - Greatly Interested in Plants. In: The American-German Review . Volume 12, August 1946, p. 20.

- ^ Heinrich Armin Rattermann: Dr. med. Georg Engelmann. In: The German Pioneer . Volume 16, 1884-1885, p. 361.

- ↑ Richard G. Beidelman: George Engelmann, Botanical gatekeeper of the West. In: Horticulture . Volume 48, Number 4, 1970, p. 58.

- ^ Transactions of the Academy of Science of St. Louis . Volume 4, February 4, 1884, pp. XC, (online) .

- ↑ Ernst Wunschmann: Engelmann, Georg . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 48, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1904, pp. 376-378.

- ↑ Members of the Society of German Natural Scientists and Doctors 1857

- ^ WE McCourt: Academy of Science of St. Louis Science. In: Science . Volume 29, Number 743, March 26, 1909, pp. 519-520, doi: 10.1126 / science.29.743.519-a .

- ^ Marshall R. Crosby: Topics in North American Botany, A Symposium Commemorating George Engelmann. In: Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden . Volume 73, Number 3, 1986, p. 503, JSTOR 2399188 .

- ^ Mike Blomberg, Chris Freeland: Digitizing Engelmann's Legacy: A project of the Missouri Botanical Garden . June 6, 2011, (accessed September 9, 2011).

- ↑ John Torrey, Asa Gray: Flora of North America . Volume 2, 1842, p. 283, (online) .

- ↑ Engelmann Peak at www.summitpost.org. (accessed on September 23, 2011).

- ↑ Bust of George Engelmann . (accessed September 5, 2011).

- ^ A b Martha Riley: A guide to the Archives and Manuscripts of the Missouri Botanical Garden . Part II. Personal Papers and Organizational Records . Missouri Botanical Garden Library, St. Louis 1995, pp. 79-81, PDF .

- ↑ Patricia P. Timberlake: George Engelmann, 1809-1884: Early Missouri Botanist. In: Missouri Folklore Society Journal , Volume 10, 1988 (Special Issue, Traditional Uses of Native Plants in Missouri), p. 6.

- ^ William G. D'Arcy: Mysteries and Treasures in Bernhardt Herbarium. In: Missouri Botanical Garden Bulletin . Volume 59, 1971, p. 23.

- ^ Edgar S. Anderson: Godfather of the Garden. In: Washington University Magazine . Volume 39, 1969, p. 43.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Engelmann, George |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Engelmann, Georg Theodor (real name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American doctor and botanist of German descent |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 2, 1809 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Frankfurt am Main |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 4, 1884 |

| Place of death | St. Louis , Missouri |