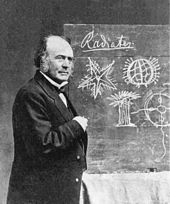

Louis Agassiz

Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz (born May 28, 1807 in Haut-Vully in the municipality of Môtier, Canton of Friborg , Switzerland ; † December 14, 1873 in Cambridge , Massachusetts , United States ) was a Swiss-American naturalist .

Agassiz was one of the first internationally renowned US scientists. Above all, his achievements as a zoologist , especially in ichthyology , his investigation of the glaciers of the Alps and as a university lecturer are sustainable . More recently, Agassiz's views on race have been viewed critically in humans.

biography

Louis Agassiz was born as the son of a Protestant pastor in Vully-le-Haut (today: Haut-Vully) in the district of Môtier, Switzerland. His younger brother Auguste Agassiz worked as a watchmaker and founded Longines' predecessor company .

First raised at home, Agassiz spent four years in secondary schools in Biel / Bienne and Lausanne . With the aim of becoming a doctor, he studied from 1824 at the University of Zurich , the Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg and the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München . In Heidelberg and Munich he was a member of the Corps Helvetia . In Heidelberg a friendship developed with the botanist Karl Friedrich Schimper , which continued when he moved to Munich in 1828, but which later broke up in a fateful way. Schimper encouraged him to study the natural sciences, and in 1828 he published his first work on fish . In 1829 he became a doctor of philosophy in Erlangen and in 1830 a doctorate in medicine in Munich doctorate . During a stay of several months in Paris, Alexander von Humboldt and Georges Cuvier became his mentors.

On the recommendation of Alexander von Humboldt had the Prince of Neuchatel, the King of Prussia ( Frederick William III. ), 1832 at the Lyceum (1838: Académie de Neuchâtel ) a professorship established for Agassiz, which this until his emigration to the United States in Year 1846. During this time he published a large number of publications, particularly on recent and fossil fish and echinoderms, with the great enthusiasm that is characteristic of him and with the help of his colleagues Édouard Desor , Amanz Gressly , Arnold Henri Guyot and Carl Vogt . With the greatest possible recognition, he published them everywhere and mostly under his name, which his employees, e. B. Carl Vogt (1896: p. 196 ff.) Did not always please.

After he had put forward his own hypothesis about the Ice Age in 1837 , he and his colleagues concentrated on examining glaciers between 1838 and 1844. He made this known to the public around the world and that is why he is still considered to be the discoverer of the Ice Age, especially in English-speaking countries, where literature in other languages is hardly considered, see the section below. In addition, he tirelessly published works z. B. on mollusks and the extensive noun zoologicus.

With the support of the King of Prussia ( Friedrich Wilhelm IV. ) He traveled to the USA in the fall of 1846 to study the natural history and geology of the United States and, at the invitation of John Amory Lowell, to give lectures on zoology in Boston , Massachusetts hold. The financial opportunities offered prompted him to settle in the USA and teach from 1847 on as a professor of zoology and geology at Harvard University . After the death of his first wife Cecile in 1848, Agassiz married the Boston writer Elisabeth Cabot Cary in 1850 , who made a name for herself as a champion of women's education . In 1852 a professorship for comparative anatomy followed in Charlestown (Massachusetts) , which he gave up two years later.

After moving to the United States, Agassiz spent less time on scientific studies, but he continued his countless publications, including the two four-volume works Natural History of the United States and Bibliographia Zoologiae et Geologiae . Due to his teaching activities, he had a great influence on the development of geology and zoology in the USA: Agassiz developed a new teaching method by establishing the connection between students and nature so that they could gain the knowledge they needed from their own experience, rather than just book knowledge to learn. As a scientist, he was noticed by the general public and was one of the most famous and respected teachers of his time. On the occasion of his 50th birthday, the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote a poem in his honor entitled "The fiftieth birthday of Agassiz".

Agassiz's students included David Starr Jordan , Joel Asaph Allen , Joseph LeConte , Nathaniel Shaler , Alpheus Spring Packard and his own son Alexander Agassiz , all of whom later made a name for themselves as scientists and teachers. Agassiz's ability to raise funds and funds also led to the establishment of the Natural History Museum in Cambridge , which opened in 1859. He was one of the first to study the effects of the last ice age in North America. From 1865 to 1866 he undertook a research expedition to Brazil, from which he brought numerous exhibits for the museum he founded. From 1871 to 1872 he also began to deal with deep water investigations.

In the last years of his life, he set himself the goal of setting up an institution where zoological studies can be carried out on living objects. In 1873 the philanthropist John Anderson gave Agassiz an island off the coast of Massachusetts and $ 50,000 to set up a station for the study of marine life. This station did not last very long after Agassiz's death, but is considered to be the forerunner of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution , which now exists near the old research station.

Louis Agassiz died in Cambridge in 1873. His tomb is a boulder from the moraine of the Aar glacier , on which his research hut once stood.

Agassiz the ichthyologist

The processing of the freshwater fish from the Brazilian rivers, especially the Amazon , which Johann Baptist von Spix and Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius also collected during a research trip to Brazil between 1819 and 1820 , had not begun due to Spix's early death. The commission by Martius helped Agassiz to get started in ichthyology. After completing the work and the publication in 1829, Agassiz dealt scientifically with the fish of Lake Geneva . As early as 1830 he extended this work to all freshwater fish from Central Europe.

In Neuchâtel he began to deal with the fossil fish that z. B. could be found in abundance in the slate layers of the Swiss canton of Glarus and in the limestone of Monte Bolca . This work later laid the basis for his worldwide fame. The five volumes and atlases of his Recherches sur les poissons fossiles appeared at intervals between 1833 and 1843. They were illustrated primarily by Joseph Dinkel. As part of his research, Agassiz visited the major museums in Europe and was encouraged by Georges Cuvier and Alexander von Humboldt to continue his work. When it became apparent that the continuation of the work was being restricted by financial constraints, he received support from the British Association and from Lord Francis Egerton , who bought drawings from him in 1290 to hand them over to the Geological Society of London .

Since the fossils often only contain teeth, scales and bone parts of the fish, he designed a classification system that contains only four groups. Its classification is outdated today, but it forms the basis of today's system.

Agassiz and the discovery of the Ice Age

Early history of the discovery of the Ice Age

Already in the second half of the 18th century naturalist employed the question of how those in the North German Plain and the foothills of the Alps often to be found non-local (erratic), and z. T. huge boulders have reached their place. The various theories put forward (→ Quaternary research ) ranged from volcanic events in which the erratic boulders would have to be hurled over huge distances as volcanic bombs , through huge floods or nebulous bumps, to transport through icebergs on a large diluvial sea. In 1832 Goethe had his Mephisto in Faust II . mock:

- The country is still staring with strange masses

- Who gives an explanation of such hurling power?

- The philosopher, he can't believe it,

- There lies the rock, you have to leave it there

- We already thought we were shameful.

But in the same year the problem was also solved by Albrecht Reinhard Bernhardi's correct conclusion that only a huge glacier stretching from the north to central Germany could be considered. However, this fundamental insight was completely ignored , although it was published in a renowned specialist journal .

Agassiz's entry into Quaternary research

When Karl Friedrich Schimper stayed with his friend Louis Agassiz from Munich days in Neuchâtel from December 1836 to May 1837 , the naturalist with a wide variety of interests also dealt with the long-discussed questions about the glaciation of the Alps and the erratic blocks on the Jura mountains . During his extensive hikes, he discovered glacier grinds near Le Landeron on Lake Biel and also near Olten by chance . These had so far escaped observation, as they had only been preserved from weathering in areas covered with loose sediments (then called “dam soil ”) .

He recognized them as an unmistakable sign that the entire Swiss Central Plateau, except for the heights of the Jura Mountains, was once filled with ice. In his own poetic way, a focus of his work were poems, he wrote the ode "Ice Age" on this knowledge and distributed it on February 15, 1837. To be announced at the 22nd annual meeting of the General Swiss Society for the Whole Natural Sciences in July In 1837 in Neuchâtel, in which he could not take part, he unsuspectingly sent an extensive letter to Louis Agassis about the discovery. He recognized the scope of the discovery and took on the matter. As President of the Society, he only presented an excerpt, which was later published. In the opening lecture, Agassiz presented his own hypothesis, which had obviously been drawn up in a hurry, and only mentioned Schimper in passing. Since his hypothesis was influenced too much by the cataclysmic theory , which had already gone out of fashion , it initially found little approval despite his great reputation. His old patron Alexander von Humboldt recommended in a letter in the same year that he should resume his work on fossil fish: "... if you do that, you are doing a greater service to positive geology than with these general considerations (also somewhat icy) about the upheavals in the primitive world, considerations which, as you well know, only convince those who bring them to life. "

According to his hypothesis, which he explained in more detail in his 1840 Études sur Les Glaciers (1841: Investigations into the glaciers ), almost the entire northern hemisphere, in Europe from the polar region across the Mediterranean to the Atlas Mountains, is supposed to be covered by an enormous "ice crust" have been covered. The rising Alps are said to have pierced the ice and the boulders falling on the ice would have slid onto the Jura mountains. In the sense of the catastrophism he advocated , "icing" is said to have been the primary event and only afterwards the glaciers are said to have retreated to their present extent. Agassiz spread his hypothesis with so much force and propagandistic skill that he was celebrated for a long time as the founder of the Ice Age theory . Although his hypothesis has proven to be false in all assumptions by recent research, he is z. B. in the USA is still called the founder of the Ice Age theory.

Agassiz and glacier research

In order to substantiate his hypothesis, he began in 1837 with an investigation of the glaciers, initially without any great technical effort. He traveled the area, mainly with his colleague Desor, and got a comprehensive overview. In the studies of the glaciers of 1841, a detailed description of the glaciers and their effects was provided based on the state of knowledge from the specialist literature . One focus is the detailed description of the previously neglected glacier cut marks and their widespread distribution, but he did not mention those at Le Landeron. According to the information in the “Historical Overview” and again in more detail from page 269 onwards, in December 1836 he was the first to discover these cut marks in the Swiss plateau. But he must have kept this a secret from Schimper, because he describes in the rudiment of Ueber the Ice Age the glacier cuts proposed for viewing at Le Landeron, which were obviously also shown on the excursion during the conference. At that time, Schimper did not win the fierce dispute about priority that was triggered .

In 1840 Agassiz traveled to England and also promoted his Ice Age theory before the British Association for the Advancement of Science . He not only convinced the leading English paleontologist William Buckland of the great role that glaciers had in shaping the landscape of Scotland , Ireland and Wales . Ultimately, however, the leading English geologist Charles Lyell established himself with his drift theory (→ Quaternary research ) in English-speaking countries and thus hindered research for 30 years.

With the support of the King of Prussia (Friedrich Wilhelm IV.) He was able to continue the investigation of the glaciers in 1842 and expand it considerably.

He invited interested colleagues to participate, which today would be called a kind of workshop , and had a hut built especially for this on the Unteraar Glacier as a research station. To research the structure and movement of the glacier drove with his colleagues u. a. a row of stakes perpendicular to the direction of flow into the ice and marked their positions on the side rock walls. On the basis of the test field it could be shown that the friction of the ice on the rock slows down its movement and that different speeds occur in the flow direction of a glacier. However, only a few relatively short publications are available on the results of this investigation stage.

Agassiz and the theory of evolution

Despite his intensive studies of the anatomy and systematics of recent and fossil fish, through which he was familiar with the graded morphological similarities and possible lines of development, Agassiz remained a supporter of the catastrophism founded by Georges Cuvier and as such a resolute opponent of the theory of evolution until his death that was developed by Charles Darwin . He argued that the common circumstances Darwin used for his theory, such as variability and hereditary changes in species, climatic changes, geological upheavals, and even ice ages, could only ever lead to the extinction of species and never to the emergence of new species. The development from simpler to more complex organisms, as emerged in the sequence of fossils , he traced back in a neo-Platonic way as "thought associations in the divine spirit". He was one of the last palaeontologists to metaphysically justify biodiversity by tracing it back to a creative god. As such, he assumed a constancy of species and tried to replace the facts of zoogeography with centers of creation (see history of geology ). This also fits in with his phrase that glaciers are "the great ploughshare of God".

His enthusiastic, emotionally tinged view of nature goes back to the influence of romantic natural philosophy , especially Friedrich Schelling - after all, Heidelberg and Munich, where Agassiz once studied, were centers of German high romanticism.

Agassiz and the racial theory

During his time in Switzerland, Agassiz was still a supporter of the monogenesis theory, which is now generally accepted. It says that all people have come from a common origin. During his years in the USA, however, he became a supporter of the then competing polygenism, according to which people in different parts of the world developed independently of one another from different origins. His encounters with black slaves, who at that time had little opportunity to develop in the USA, contributed to this change of opinion. Agassiz had a very bad impression of them, as he described in a letter to his mother.

Agassiz did not comment on this subject in specialist publications, but he certainly wrote the article The diversity of origin of the human races , published in 1850 in the Christian journal Christian Examiner with the author's indication LA, and Charles Darwin's 1871 book Die Human descent and sexual selection was cited. Agassiz also commented on this in some letters, following quotations from Stephen Jay Gould (1988).

Because of Agassiz's stance, the Swiss parliamentarian Carlo Sommaruga wanted to rename the Agassizhorn, named after the researcher, in 2007 . The Swiss Federal Council condemned Agassiz's racist views , but saw no reason to rename the mountain top. The "Transatlantic Committee Démonter Louis Agassiz" around the St. Gallen historian and politician Hans Fässler is continuing the campaign to reassess Louis Agassiz. On September 7, 2018, the city council of Neuchâtel announced that, in consultation with the university, it had decided to rename the "Espace Louis Agassiz" on the grounds of the human sciences to "Espace Tilo Frey" because of the racism of its namesake. Tilo Frey was Switzerland's first colored national councilor and was elected to the federal parliament in 1971 for the FDP Neuchâtel. Her father was Swiss and her mother was from Cameroon.

Memberships

- In 1835 he became a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh .

- In 1836 he became a corresponding member of the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin .

- In 1838 he was appointed a foreign member of the British Royal Society .

- In 1838 he was accepted into the Leopoldina .

- In 1839 he became a corresponding member of the French Académie des Sciences .

- In 1843 he was accepted into the American Philosophical Society .

- In 1846 he was accepted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences .

- In 1851 he was president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science .

- In 1853 the Bavarian Academy of Sciences appointed him a foreign member.

- In 1859 he became a foreign member of the Göttingen Academy of Sciences .

- In 1860 he was accepted as a foreign member of the Prussian order Pour le Mérite for science and the arts .

- In 1863 he was one of the founding members of the American National Academy of Sciences .

- In 1869 he became a foreign corresponding member of the Russian Academy of Sciences .

- In 1872 he became a foreign member of the «Académie des sciences».

Honors

- In 1836 Agassiz was awarded the Wollaston Medal for his work .

- In 1879 the former huge Agassizsee was named after him. This had formed from glacial melt water at the end of the Pleistocene in North America and covered large parts of Canada in the Old Holocene .

- In 1947 Cape Agassiz on the Antarctic Peninsula was named after him.

- The asteroid of the main inner belt (2267) Agassiz , discovered in 1977, was named after him.

- A crater on Mars (planet) bears his name.

- On the Earth's moon was promontory Agassiz named after him.

- The 3,946 m high Agassizhorn in the Bernese Alps bears his name: it is separated from the southeastern Finsteraarhorn , Bern's highest peak, by the 3,749 m high Agassizjoch .

- Some animal species were named after him: z. B. the Agassiz 'dwarf cichlid ( Apistogramma agassizii ) and the California gopher tortoise ( Gopherus agassizii ).

Publications (selection)

- Descriptio speciei novae e genere: Cynocephalus Briss. Leipzig 1828

- Description of a new species from the genus Cyprinus Linn. Leipzig 1828

- Selecta genera et species Piscium: quos in itinere per Brasiliam. Munich 1829

- Cyprinus uranoscopus, nouvelle espece trouvée. Paris 1829

- Investigations into the fossil freshwater fish of the tertiary formations. Heidelberg 1832

- Investigations into the fossil fish of the Lias formation. Heidelberg 1832

- Research on the poissons fossiles. 5 volumes. Neuchâtel 1833–1843

- Recherches sur les poissons fossiles: Atlas. 5 volumes. Neuchâtel 1833–1843

- Synoptic overview of the fossil ganoids. Stuttgart 1833

- New discoveries about fossil fish. Stuttgart 1833

- About the age of the Clarner slate formation, according to its fish remains. Stuttgart 1834

- About the echinoderms. Leipzig 1834

- Disrupted Remarks on Fossil Fish. Stuttgart 1834

- About belemnites. Stuttgart 1835

- About the salmon-like fish. Berlin 1835

- Critical revision of the fossil fish depicted in the 'Ittiolitologia Veronese'. Stuttgart 1835

- Report on the poissons fossiles decouverts en Angleterre. Stuttgart 1835

- About the natural relationships and the generic division of the cyprinoids. Berlin 1836

- Note about the fossil remains of the chalk formation in the Neuchateler Jura. Stuttgart 1837

- Prodome d'une monographie des Radiaires et des Echinodermes. Stuttgart 1837

- Discours prononcé a l'ouverture des séanes de la Société Helvétique des Sciences Naturelles. Neuchâtel 1837

- Monographies d'échinodermes, vivans et fossiles. Neuchâtel 1838

- Artificial stone cores of conchylia. Stuttgart 1838

- Theory of erratic blocks in the Alps. Stuttgart 1838

- Mémoire sur les moules de mollusques vivans et fossiles. Neuchâtel 1839

- Description of the Echinodermes fossils de la Suisse. 2 parts. Neuchâtel 1839–1840

- Études critiques sur les mollusques fossils. Neuchâtel 1840–1845

- Catalogus systematicus ectyporum echinodermatum fossilium Musei Neocomensis. Neuchâtel 1840

- Études sur Les Glaciers. Neuchâtel 1840

- Glacier studies with Studer. Stuttgart 1840

- Against Wissmann's view of the origin of erratic blocks. Stuttgart 1840

- Studies on the glaciers. Solothurn 1841

- Genus Trigonia and glacier theory. Stuttgart 1841

- A period in the history of our globe. Stuttgart and Tübingen 1841

- Old moraines near Baden-Baden. Stuttgart 1841

- On the polished and striated surfaces of the rocks which from the beds of Glaciers in the Alps. London 1842

- A paper was read on Glaciers, and the evidence of their having once existed in Scotland, Ireland, and England. London 1842

- The Glacial Theory and its recent progress. Edinburgh 1842

- Journey to the Aar Glacier. Stuttgart 1842

- Histoire naturelle des poissons d'eau douce de l'Europe centrale. Neuchâtel 1842

- Nomenclator zoologicus. Solothurn 1842–1846

- Concerning the succession and development of organized beings on the surface of the earth in the different ages. Hall 1843

- Observation on the Aar glacier in the summer of 1942. Stuttgart 1843

- Notice on the succession des poissons fossils in the serie des formations géologiques. Neuchâtel 1843

- New observations on the glaciers. Stuttgart 1843

- Structure of the glacier. Stuttgart 1843

- Movement of glaciers. Stuttgart 1844

- Monograph des poissons fossiles du vieux grès rouge ou Système Dévonien (Old Red Sandstone) des Îles Britanniques et de Russie. Neuchâtel 1844

- Des poissons fossiles du vieux grès rouge. Neuchâtel (?) 1844

- Iconography des coquilles tertiaires. Neuchâtel 1845

- Anatomy of the salmon. Neuchâtel 1845

- Système glaciaire or recherches on the glaciers. Paris 1847

- Principles of Zoology. Boston 1848

- Bibliographia zoologiæ et geologiæ. A general catalog of all books, tracts, and memoirs on zoology and geology. 4 volumes. London 1848-1854

- Lake Superior: its physical character, vegetation, and animals, compared with those of other and similar regions. Boston 1850

- The classification of insects from embryological data. Cambridge 1850

- Contributions to the Natural History of the Acalephae of North America. Boston 1850

- The Diversity of Origin of the Human Races. Boston 1850

- Directions for collecting fishes and other objects of natural history. Cambridge 1853

- Natural history of the animal kingdom, with special regard to trade, arts and practical life. Stuttgart 1855

- Contributions to the natural history of the United States of America. 4 volumes. Boston 1857-1862

- An essay on classification. London 1859

- Methods of study in natural history. Boston 1863

- The classification of the animal kingdom. Marburg 1866

- A journey in Brazil. Boston 1868

- De l'espèce et de la classification en zoologie. Paris 1869

- The plan of creation. Lectures on the natural foundations of kinship among animals. Leipzig 1875

Secondary literature

- William Buckland (1839): Geology and Mineralogy in Relation to Natural Theology. (Translated from English from the second edition of the original and annotated and added by L. Agassiz). 2 volumes. Neuchâtel (Petitpierre) 1839. Volume 1: S. XII, 1-664. Volume 2: Text to 88 plates. [70]

- Édouard Desor (1842): The ascent of the Jungfrauhorn by Agassiz and his companions (from the French by C. Vogt). Solothurn (Jent and Gaßmann) 1842. pp. 1-96. [71]

- Édouard Desor (1844): Agassiz geological trips to the Alps. (With the assistance of Agassiz, written by É. Desor. Deutsch with a topographical introduction to the high mountain groups by Carl Vogt). Frankfurt am Main (Rütten). Pp. 1-548. [72]

- Édouard Desor (1847): Agassiz 'and his friends geological trips to the Alps in Switzerland, Savoy and Piedmont. (With Agassiz ', Studer's and Carl Vogt's participation written by É. Desor. Edited by Carl Vogt). 2nd Edition. Frankfurt am Main (Horstmann) 1847. S. XXXVI, 1-672, 3 plates. [73]

- Oscar Schmidt (1870): Louis Agassiz 'report on the investigation of the Gulf Stream bed in the spring of 1869. In: Abroad: Survey of the latest research in the field of natural, earth and ethnology. 43rd year, No. 4. Augsburg (Cotta). Pp. 82-85. [74]

- Elizabeth Cabot Cary Agassiz (1885): Louis Agassiz: his life and correspondence. Boston and New York (Houghton Mifflin Company) 1885. S. XVIII, 1-794. [75]

- Elisabeth Cary Agassiz (1886): Louis Agassiz's life and correspondence (authorized German edition by Cecile Mettenius). Berlin (Reimer). S. X, 1-448. [76]

- Jules Marcou (1896a): Life, Letters, and Works of Louis Agassiz. Volume 1. New York (Macmillan and Co.). S. XXI, 1-302. [77]

- Jules Marcou (1896b): Life, Letters, and Works of Louis Agassiz. Volume 2. New York (Macmillan and Co.). P. IX, 1-318. [78]

- Carl Vogt (1896): From my life: memories and reviews. Stuttgart (Nägele). P. 196 ff. [79]

- Robert Lauterborn (1934): The Rhine. Natural history of a German river. 1st volume. In: Reports of the Natural Research Society in Freiburg im Breisgau. Volume 33. Freiburg. P. 78 ff. [80]

- Stephen Jay Gould (1988): The wrongly measured man (German translation by Günter Seibt). Suhrkamp Verlag. 394 pp. ISBN 978-3-518-28183-3 .

- Edward Lurie (1988): Louis Agassiz. A Life in Science. Baltimore. ISBN 0-8018-3743-X .

- Christine Reinke-Kunze (1996): The Pack ICE Waffle - From glaciers, snow and ice cream. Basel. ISBN 3-7643-5331-7 .

- Edmund B. Bolles (2000): Ice Age. How a professor, a politician and a poet discovered the eternal ice. Berlin. ISBN 3-87024-522-0 .

- Jeroen Dewulf (2007): Brazil with Breaks. Swiss under the Southern Cross. Zurich. ISBN 978-3-03823-349-7 .

Web links

- Publications by and about Louis Agassiz in the Helveticat catalog of the Swiss National Library

- Literature by and about Louis Agassiz in the catalog of the German National Library

- Publications BBAW (PDF; 39 kB)

- Works by and about Louis Agassiz in the German Digital Library

- Collection of texts by Louis Agassiz in Gallica

- Hans Barth, Hans Fässler : Agassiz, Louis. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Personal folder for Jean-Louis Rudolphe Agassiz (collection of materials). (PDF; 1.8 MB) Historical Alpine Archives of the Alpine Clubs in Germany, Austria and South Tyrol, accessed on November 13, 2011 .

- Images and texts from Excursions et séjours dans les glaciers et les hautes régions des Alpes and from Nouvelles études et expériences sur les glaciers actuels by Louis Agassiz can be found on the VIATIMAGES portal.

- Digital version of volume 3 of RECHERCHES SUR LES POISSONS FOSSILES (fossil sharks, rays and chimeras)

- Louis Agassiz in the database of Find a Grave (English)

- Swissinfo.ch: can natural scientist Louis Agassiz be compared with Hitler? Retrieved May 26, 2016 .

Footnotes

- ↑ Kösener corps lists 1910, 115/51; 172a / 5

- ↑ Josef Dinkel en: Joseph Dinkel

- ↑ Albrecht Bernhardi: How did the rock fragments and debris from the north, which can be found in northern Germany and the neighboring countries, get to their current location? In: Yearbook for Mineralogy, Geognosy, Geology and Petrefactology. 3rd year. Heidelberg 1832. pp. 257-267. [1]

- ^ Karl Friedrich Schimper: About the Ice Age (excerpt from a letter to L. Agassiz). In: Actes de la Société Helvétique des Sciences Naturelles. 22nd session. Neuchâtel 1837. pp. 38–51. [2]

- ^ A b Louis Agassiz: Discours prononcé a l'ouverture des séanes de la Société Helvétique des Sciences Naturelles, a Neuchatel le 24 Juillet 1837, par L. Agassiz, president. In: Actes de la Société Helvétique des Sciences Naturelles. 22nd session. Neuchâtel 1837. S. V – XXXII. [3]

- ↑ Reinke-Kunze, p. 112

- ^ A b Louis Agassiz: Genus Trigonia and glacier theory. In: New yearbook for mineralogy, geognosy, geology and petrefacts. Born in 1841. Stuttgart (Schweizerbart) 1841. pp. 356–366. [4]

- ↑ a b Louis Agassiz: Theory of the erratic blocks in the Alps. In: New yearbook for mineralogy, geognosy, geology and petrefacts. Born in 1838. Stuttgart (Schweizerbart) 1838. pp. 304–305. [5]

- ^ A b Louis Agassiz: A paper was read on Glaciers, and the evidence of their having once existed in Scotland, Ireland, and England. In: Proceedings of the Geological Society of London. Volume 3, Part 2, No. 72. London (Taylor) 1842. pp. 327-348. [6]

- ↑ a b Louis Agassiz: Journey to the Aar Glacier. In: New yearbook for mineralogy, geognosy, geology and petrefacts. Born in 1842. Stuttgart (Schweizerbart) 1842. pp. 313–317. [7]

- ↑ shaper RSE Fellows 1783-2002. Royal Society of Edinburgh, accessed October 4, 2019 .

- ^ Member entry of Jean-Louis-Rodolphe Agassiz at the German Academy of Natural Scientists Leopoldina , accessed on February 3, 2016.

- ^ Member entry of Louis Agassiz (with picture) at the Bavarian Academy of Sciences , accessed on February 3, 2016.

- ↑ Holger Krahnke: The members of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen 1751-2001 (= Treatises of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen, Philological-Historical Class. Volume 3, Vol. 246 = Treatises of the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen, Mathematical-Physical Class. Episode 3, vol. 50). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2001, ISBN 3-525-82516-1 , p. 24.

- ↑ The Order Pour le Mérite for Sciences and Arts : The Members of the Order, Volume I (1842–1881), Gebr. Mann-Verlag, Berlin, 1975 p. 210

- ^ Foreign members of the Russian Academy of Sciences: Agassiz, Jean Louis Rodolphe. Russian Academy of Sciences, accessed August 26, 2019 (in Russian).

- ^ List of members since 1666: letter A. Académie des sciences, accessed on September 30, 2019 (French).

- ^ Lutz D. Schmadel : Dictionary of Minor Planet Names . Fifth Revised and Enlarged Edition. Ed .: Lutz D. Schmadel. 5th edition. Springer Verlag , Berlin , Heidelberg 2003, ISBN 978-3-540-29925-7 , pp. 185 (English, 992 pp., Link.springer.com [ONLINE; accessed on November 3, 2017] Original title: Dictionary of Minor Planet Names . First edition: Springer Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg 1992): “Named in memory of Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz (1807–1873) ”

- ↑ promontory Agassiz the-moon.wikispaces.com, accessed 2 April 2012

- ↑ Louis Agassiz: Descriptio speciei novae e genere: Cynocephalus Briss. In: Isis von Oken. Volume 21. Leipzig (Brockhaus) 1828. Columns 861–863. [8th]

- ↑ Louis Agassiz: Description of a new species from the genus Cyprinus Linn. In: Isis von Oken. Volume 21. Leipzig (Brockhaus) 1828. Columns 1046-1049. 1 board. [9]

- ^ Louis Agassiz: Selecta genera et species Piscium: quos in itinere per Brasiliam. Monachia (Wolf) 1829. S. XVI, 1-138, Plates I-LXXVI and A-F and A-G. [10]

- ^ Louis Agassiz: Cyprinus uranoscopus, nouvelle espèce trouvee. In: Bulletin des sciences naturelles et de geology. Tome 19, No. 10. Paris 1829. pp. 117-118. [11]

- ↑ Louis Agassiz: Investigations into the fossil freshwater fish of the tertiary formations. In: Yearbook for Mineralogy, Geognosy, Geology and Petrefactology. 3rd year. Heidelberg (Reichard) 1832. pp. 129-138. [12]

- ↑ Louis Agassiz: Investigations into the fossil fish of the Lias formation. In: Yearbook for Mineralogy, Geognosy, Geology and Petrefactology. 3rd year. Heidelberg (Reichard) 1832. pp. 139-149. [13]

- ^ Louis Agassiz: Recherches sur les poissons fossiles. 5 volumes. Neuchâtel (Petitpierre) 1833 to 1843. Tome 1: S. XLIX, 1–188. Tome 2: pp. XII, 1-338. Tome 3: pp. VIII, 1-32. Tome 4: S. XVI, 1-296 and 1-22. Tome 5: S. XII, 1-12 and 1-160. [14]

- ↑ Louis Agassiz: Recherches sur les poissons fossiles: Atlas. 5 volumes. Neuchâtel (Nicolet) 1833–1843. Volume 1: 1 page, plates A – K. Volume 2: 2 pages, plates A – J and 1–75. Volume 3: 1 page, plates A – S and 1–47. Volume 4: 1 page, plates A – L and 1–44. Volume 5: 1 page, plates A – M and 1–64. [15]

- ↑ Louis Agassiz: Synoptic overview of the fossil ganoids. In: New yearbook for mineralogy, geognosy, geology and petrefacts. Born in 1833. Stuttgart (Schweizerbart) 1833. pp. 470–481. [16]

- ↑ Louis Agassiz: New discoveries about fossil fish. In: New yearbook for mineralogy, geognosy, geology and petrefacts. Born in 1833. Stuttgart (Schweizerbart) 1833. pp. 675–677. [17]

- ↑ Louis Agassiz: About the age of the Clarner schist formation, after their fish remains. In: New yearbook for mineralogy, geognosy, geology and petrefacts. Born in 1834. Stuttgart (Schweizerbart) 1834. pp. 301–306. [18]

- ↑ Louis Agassiz: About the Echinoderms. In: Isis von Oken. Volume 27. Leipzig (Brockhaus) 1834. Columns 254-257. [19]

- ↑ Louis Agassiz: Torn Remarks on Fossil Fish. In: New yearbook for mineralogy, geognosy, geology and petrefacts. Born in 1834. Stuttgart (Schweizerbart) 1834. pp. 379–390. [20]

- ↑ Louis Agassiz: About Belemnites. In: New yearbook for mineralogy, geognosy, geology and petrefacts. Born in 1835. Stuttgart (Swiss beard) 1835. P. 168. [21]

- ↑ Louis Agassiz: About the salmon-like fish. In: Archives for Natural History. 1st year, 2nd volume. Berlin (Nicolai) 1835. pp. 265-268. [22]

- ↑ Louis Agassiz: Critical revision of the fossil fish depicted in the 'Ittiolitologia Veronese'. In: New yearbook for mineralogy, geognosy, geology and petrefacts. Born in 1835. Stuttgart (Schweizerbart) 1835. pp. 290–316. [23]

- ^ Louis Agassiz: Rapport sur les poissons fossiles découverts en Angleterre. In: New yearbook for mineralogy, geognosy, geology and petrefacts. Born in 1835. Stuttgart (Schweizerbart) 1835. pp. 491–494. [24]

- ↑ Louis Agassiz: About the natural relationships and the generic division of the cyprinoids. In: Archives for Natural History. 2nd year, 2nd volume. Berlin (Nicolai) 1836. pp. 240-242. [25]

- ↑ Louis Agassiz: Note on the fossil remains of the chalk formation in the Neuchateler Jura. In: New yearbook for mineralogy, geognosy, geology and petrefacts. Born in 1837. Stuttgart (Schweizerbart) 1837. pp. 102–103. [26]

- ^ Louis Agassiz: Prodome d'une monographie des Radiaires et des Echinodermes. In: New yearbook for mineralogy, geognosy, geology and petrefacts. Born in 1837. Stuttgart (Schweizerbart) 1837. pp. 223–237. [27]

- ↑ Louis Agassiz: Monographies d'échinodermes, vivans et fossiles. Neuchâtel 1838. P. VIII, 1–32, 5 plates. [28]

- ^ Louis Agassiz: Artificial stone cores of conchylia. In: New yearbook for mineralogy, geognosy, geology and petrefacts. Born in 1838. Stuttgart (Schweizerbart) 1838. pp. 49–51. [29]

- ^ Louis Agassiz: Mémoire sur les moules de mollusques vivans et fossiles. 1st part: Moules d'acéphales vivans. Neuchâtel (Petitpierre) 1839. pp. 1–48, 9 plates. [30]

- ^ Louis Agassiz: Description of the Echinodermes fossils de la Suisse. Neuchâtel (Jent & Gassmann) 1839–1840. Part 1: pp. VIII, 1–101, plates 1–13. Part 2: pp. IV, 1–107, plates 14-23. [31]

- ↑ Louis Agassiz: Études critiques sur les mollusques fossils. Neuchâtel (Petitpierre) 1840–1845. Part 1 (1840): pp. II, 1-58, 11 plates. Part 2 (1845): pp. XX, 1-141, 48 plates. Part 3 (1845): pp. 144-287, 46 plates. [32]

- ↑ Louis Agassiz: Catalogus systematicus ectyporum echinodermatum fossilium Musei Neocomensis: secundum ordinem zoologicum dispositus: adjectis synonymis recentioribus, nec non stratis et locis in quibus reperiuntur: sequuntur characteres diagnostici generum novorum vel minus cognitorum. Neuchâtel (Petitpierre) 1840. pp. 1–20. [33]

- ^ Louis Agassiz: Études sur Les Glaciers. Neuchâtel (Jent and Gassmann) 1840. S. V, 1–347. [34]

- ^ Louis Agassiz: Glacier studies with Studer. In: New yearbook for mineralogy, geognosy, geology and petrefacts. Born in 1840. Stuttgart (Schweizerbart) 1840. pp. 92–93. [35]

- ↑ Louis Agassiz: Against Wissmann's view of the origin of erratic blocks. In: New yearbook for mineralogy, geognosy, geology and petrefacts. Born in 1840. Stuttgart (Schweizerbart) 1840. pp. 575–576. [36]

- ^ Louis Agassiz: Investigations on the glaciers (German translation by Carl Vogt). Solothurn (Jent and Gassmann) 1841. S. XII, 1-327. [37]

- ↑ Louis Agassiz: A Period in the History of Our Globe. In: German quarterly font. 3rd issue. Stuttgart and Tübingen (Cotta) 1841. pp. 88-151. [38]

- ↑ Louis Agassiz: Old Morainen near Baden-Baden. In: New yearbook for mineralogy, geognosy, geology and petrefacts. Born in 1841. Stuttgart (Schweizerbart) 1841. pp. 566–567. [39]

- ^ Louis Agassiz: On the polished and striated surfaces of the rocks which from the beds of Glaciers in the Alps. In: Proceedings of the Geological Society of London. Volume 3, Part 2, No. 72. London (Taylor) 1842. pp. 321-322. [40]

- ^ Louis Agassiz: The Glacial Theory and its recent progress. In: The Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal. Volume 33. Edinburgh 1842. pp. 217-283. [41]

- ↑ Louis Agassiz, Carl Vogt: Histoire naturelle des poissons d'eau douce de l'Europe centrale. Neuchâtel (Petitpierre) 1842. S. VI, 1–326. [42]

- ↑ Louis Agassiz: Nomenclator zoologicus: continens nomina systematica generum animalium tam viventium quam fossilium, secundum ordinem alphabeticum disposita, adjectis auctoribus, libris, in quibus reperiuntur, anno editionis, etymologia et familiis, ad quas pertinent class, in. Solothurn (Jent & Gassmann) 1842–1846. [43]

- ↑ Louis Agassiz: On the succession and development of the organized beings on the surface of the earth in the different ages. (Speech at the inauguration of the Academy in Neuschatel on November 18, 1841. Translated from the French by N. Gräger). Halle / Saale (Gräger) 1843. pp. 1–15. [44]

- ↑ Louis Agassiz: Observation on the Aar glacier in the summer of 1942. In: New year book for mineralogy, geognosy, geology and petrefacts. Born in 1843. Stuttgart (Schweizerbart) 1843. pp. 364–366. [45]

- ^ Louis Agassiz: Notice sur la succession des poissons fossils in la série des formations géologiques. Neuchâtel (Petitpierre) 1843. pp. I-XLIX. [46]

- ^ Louis Agassiz: New observations on the glaciers. In: New yearbook for mineralogy, geognosy, geology and petrefacts. Born in 1843. Stuttgart (Schweizerbart) 1843. pp. 84–86. [47]

- ^ Louis Agassiz: Structure of the glaciers. In: New yearbook for mineralogy, geognosy, geology and petrefacts. Born in 1843. Stuttgart (Schweizerbart) 1843. pp. 86–89. [48]

- ^ Louis Agassiz: Movement of the glaciers. In: New yearbook for mineralogy, geognosy, geology and petrefacts. Born in 1844. Stuttgart (Schweizerbart) 1844. pp. 620–621. [49]

- ↑ Louis Agassiz: Monograph des poissons fossils du vieux grès rouge, ou Système Dévonien (Old Red Sandstone) des Îles Britanniques et de Russie. Neuchâtel (Jent & Gassmann) 1844. S. XXXVI, 1–171. [50]

- ↑ Louis Agassiz: Introduction a une monographie des poissons fossiles du vieux grès rouge. Neuchâtel (?) 1844. pp. 1–28, 1–8. [51]

- ^ Louis Agassiz: Iconographie des coquilles tertiaires. In: New Memoranda of the General. Swiss Society for the Whole Natural Sciences. Volume VII / 3. Neuchâtel (Wolfrath) 1845. pp. 1–66, 14 plates. [52]

- ^ Louis Agassiz, Carl Vogt: Anatomie des salmones. Neuchâtel (Wolfrath) 1845. pp. 1–196, panels A – O. [53]

- ^ Louis Agassiz, Arnold Henri Guyot , Édouard Desor : Système glaciaire ou recherches sur les glaciers, leur mécanisme, leur ancienne extension et le rôle qu'ils ont joué dans l'histoire de la terre. Paris (Masson) 1847. pp. XXXI, 1-598. [54]

- ↑ Louis Agassiz, Augustus Addison Gould : Principles of Zoology: touching the structure, development, distribution, and natural arrangement of the races of animals, living and extinct: with numerous illustrations: Part I, Comparative physiology: for the use of Schools and Colleges . Boston (Gould, Kendall and Lincoln) 1848. pp. XIX, 1-216. [55]

- ↑ Louis Agassiz: Bibliographia zoologiæ et geologiæ. A general catalog of all books, tracts, and memoirs on zoology and geology. 4 volumes. London 1848-1854. Volume 1 (A to Byw, 1848): pp. XXIII, 1-506. Volume 2 (Cab to Fyf, 1850): pp. 1-492. Volume 3 (Gab to Myl, 1852): pp. 1-657. Volume 4 (Nac to Zwi, 1854): pp. 1-604. [56]

- ^ Louis Agassiz: Lake Superior: its physical character, vegetation, and animals, compared with those of other and similar regions. Boston (Gould, Kendall and Lincoln) 1850. pp. X, 1-428, 8 plates. [57]

- ↑ Louis Agassiz: The classification of insects from embryological data. In: Smithsonian contributions to knowledge. Volume 2. Cambridge (Metcalf and Co.) 1850. pp. 1-28, 1 plate. [58]

- ^ Louis Agassiz: Contributions to the Natural History of the Acalephae of North America. In: American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Boston 1850. pp. 221-388, Plates I-VIII, 1-8. [59]

- ^ Louis Agassiz: The Diversity of Origin of the Human Races. In: The Christian examiner. Volume 49. Boston (Crosby and Nichols) 1850. pp. 110-145. [60]

- ↑ Louis Agassiz: Directions for collecting fishes and other objects of natural history. Cambridge 1853. 3 pages (manuscript). [61]

- ↑ Louis Agassiz, Augustus Addison Gould: Natural history of the animal kingdom, with special regard to trade, arts and practical life. Stuttgart (Müller) 1855. pp. 1-224. [62]

- ^ Louis Agassiz: Contributions to the natural history of the United States of America. Boston (Little, Brown and Co.) 1857-1862. Volume 1 (1857): S. L, 1-451. Volume 2 (1857): pp. 452-643, plates I-XXVII. Volume 3 (1860): pp. XI, 1–301, 1–26, plates I – XIX. Volume 4 (1862): pp. VIII, 1–380, 1–12, plates XX – XXXV. [63]

- ↑ Louis Agassiz: An essay on classification. London (Longman, Brown, Green et al.) 1859. pp. VIII, 1-381. [64]

- ^ Louis Agassiz: Methods of study in natural history. Boston (Ticknor and Fields) 1863. pp. VIII, 1-319. [65]

- ^ Louis Agassiz: The Classification of the Animal Kingdom. (Translated from English by Chr. Hempfing). Marburg (Ehrhardt) 1866. pp. IV, 1-68. [66]

- ^ Louis Agassiz, Elizabeth Cary Agassiz: A journey in Brazil. 2nd Edition. Boston (Ticknor and Fields) 1868. pp. XIX, 1-540. [67]

- ↑ Louis Agassiz: De l'espèce et de la classification en zoologie. Paris (Bailliere) 1869. pp. 1-400. [68]

- ↑ Louis Agassiz: The plan of creation. Lectures on the natural foundations of kinship among animals (translated and edited by Christian Gottfried Giebel ). Leipzig (Quandt & Handel) 1875. S. XII, 1–185. [69]

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Agassiz, Louis |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Agassiz, Johann Ludwig Rudolf |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Swiss-American naturalist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 28, 1807 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Môtier , municipality of Haut-Vully , Canton of Friborg , Switzerland |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 14, 1873 |

| Place of death | Cambridge , Massachusetts , United States |